Abstract

Introduction

To improve maternal and fetal outcomes among patients with obstructed labour (OL) in low-resource settings, the associated electrolyte and metabolic derangements must be adequately corrected. Oral fluid intake during labour and preoperative intravenous fluid replacement following OL corrects the associated dehydration and electrolyte changes, but it does not completely reverse the metabolic acidosis, that is, a cause of intrapartum birth asphyxia and a risk factor for primary postpartum haemorrhage due to uterine atony. Sodium bicarbonate is a safe, effective, cheap and readily available acid buffer, that is widely used by sportspeople to improve performance. It also appears to improve fetal and maternal outcomes in abnormally progressing labour. However, its effects on maternal and fetal outcomes among patients with OL is unknown. We aim at establishing the effect of a single-dose preoperative infusion of sodium bicarbonate on maternal and fetal lactate levels and clinical outcomes among patients with OL.

Methods and analysis

This will be a double blind, randomised controlled clinical phase IIb trial. We will randomise 478 patients with OL to receive either 50 mL of placebo with standard preoperative infusion of normal saline (1.5 L) or 4.2 g of sodium bicarbonate solution (50 mL of 50 mmol/L) with the preoperative infusion of normal saline (1.5 L). The primary outcome will be mean lactate levels in maternal capillary blood at 1 hour after study drug administration and in the arterial cord blood at birth. We will use the intention-to-treat analysis approach. Secondary outcomes will include safety, maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality up to 14 days postpartum.

Ethics and dissemination

Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology have approved the protocol. Each participant will give informed consent at enrollment.

Trial registration number

PACTR201805003364421

Keywords: sodium bicarbonate, obstructed labour, blood lactate level, fetal medicine, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is among the first studies to investigate the effect of preoperative bicarbonate infusion on maternal and fetal outcomes among patients with obstructed labour (OL), using a randomised control design.

Measurement of maternal lactate levels and fetal cord blood lactate at the bedside using a hand-held device (Lactate Pro2), instead of a blood gas analyser, that is, expensive to acquire and operate; in a resource-limited setting.

This study will only ascertain the efficacy and not the effectiveness of the preoperative sodium bicarbonate infusion.

Given the short duration of follow-up, we will not have any information regarding the long-term effects of sodium bicarbonate on maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Improving maternal and fetal lactate levels may not improve the fetal outcome in OL, as the tocolytic effect of the lactate may be a fetal protective mechanism.

Introduction

Globally, the annual number of maternal deaths (MDs) has decreased from 532 000 in 1990 to 303 000 in 2015.1 2 But almost all of them (99.6%) occur in sub-Saharan Africa (66.3%) and South Central Asia,1 where it is estimated that the lifetime risk of MD is as high as 1 in 16 and 1 in 46, respectively, compared with 1 in 2800 in developed regions.1 2 Although primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) and sepsis are the leading causes of MD, obstructed labour (OL) indirectly contributes to >70% of these deaths.3 Directly, OL causes 8% of all the MD4 5 and up to 90% of the perinatal deaths due to birth asphyxia.6 In the 2015/2016 financial year, of the 246 MDs reported to the Uganda Ministry of Health (MOH), 9% were due to OL, 39% were due to haemorrhage and 20% were due to sepsis.7 In addition, 69.3% of 411 perinatal deaths were due to birth asphyxia, although the contribution of OL was not specified.

The prevalence of OL varies from 2% to 8% worldwide. It is highest in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) and is almost non-existent in developed countries.4 5 In LMICs, many patients experience delays in accessing quality emergency obstetric and neonatal care services, so they end up with neglected OL which causes significant maternal morbidity (dehydration, uterine rupture, sepsis, vesicovaginal/rectovaginal fistulae and postpartum haemorrhage) and neonatal morbidity (asphyxia and sepsis).3 8 OL occurs when the fetal presenting part does not descend into the maternal pelvis despite adequate uterine contractions.4 Usually, the obstruction can only be safely relieved by an operative delivery.6 In fact, OL is the most common indication for primary caesarean section and a major risk factor for infective morbidity (puerperal and neonatal sepsis) especially in LMICs.3 9

OL is associated with higher levels of lactate in blood and amniotic fluid compared with normal labour, and this correlates directly with perinatal outcomes.10 Lactate is a byproduct of anaerobic respiration, that is, produced by both the fetus and the myometrium in response to intermittent hypoxia during labour.11 In OL, the episodes of hypoxia are prolonged leading to accumulation of lactic acid (metabolic acidosis) from anaerobic break down of glucose. Although impaired uterine contractility caused by myometrial acidosis increases the risk of primary PPH, it is beneficial to the fetus because it increases fetal placental circulation (oxygenation) which is protective against intrapartum birth asphyxia.10 12 The transfer of excess hydrogen ions across the placenta to the fetus is associated with low fetal pH, fetal distress and poor Activity Pulse Grimace Appearance Respiration (APGAR).13

Oral bicarbonate is a widely used acid buffer in sports science, to improve physical performance in vigorous exercises because it can reverse lactic acidosis.14 Bicarbonate does not cross the placental barrier,15 but it plays a key role in regulating the maternal and fetal acid–base chemistry.13 There are conflicting reports regarding its benefits in labour. Earlier studies involving the use of bicarbonate in normal labour showed improvements in pH, base excess and plasma bicarbonate, but none reported APGAR scores. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) involving the use of oral bicarbonate solution in abnormal (dystocic) labour reported a significant improvement in both maternal and perinatal outcomes.14 Significantly, none of these studies reported adverse maternal and perinatal effects or included participants with OL. Currently, preoperative intravenous infusion with at least 1.5 L of fluid is recommended as a key element of the standard care. This is adequate to correct the dehydration and electrolyte imbalance but it probably does not completely reverse the associated metabolic acidosis.16 17

Various formulations and doses of sodium bicarbonate have been safely used for both clinical indications and research purposes with no reported adverse clinical reactions. A single preoperative infusion of 4.2 g of sodium bicarbonate solution (50 mL of 50 mmol/L) will be given as a single dose at enrolment, since OL is an obstetric emergency that requires urgent intervention.18 The same dose was used orally in the recent trial in which bicarbonate solution was administered to women with dystocia in labour.14 The main outcome of this study will be to assess whether bicarbonate changes the maternal and fetal lactate levels among patients with OL. Lactate is easier to measure than full blood gas analysis using maintenance free, battery operated pocket size devices like the Lactate Pro2 (Arkray Factory, Shiga, Japan). This device produces accurate results in a short time with a high intraclass correlation coefficient which is comparable to that of gold standard in a given population, that is, 0.90 versus 0.92.18 Lactate is comparable to pH and base deficit with respect to sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of various perinatal complications.13

We hypothesise that supplementation with preoperative sodium bicarbonate infusion as an acid buffer among patients with OL can reduce maternal acidosis at 1 hour after administration, while their newborns in the bicarbonate group will have less acidosis in cord blood at birth. Bicarbonate is safe, effective, cheap and already widely used.19 Establishing its effect on maternal and fetal outcomes following OL is necessary, because it could be added to the standard preoperative care package as a form of tertiary prevention. This study aims to establish the effect of a single-dose preoperative infusion of sodium bicarbonate on maternal and fetal lactate levels and clinical outcomes among patients with OL.

Methods/design

Study design

This will be a superiority, double blind, randomised controlled clinical phase IIb trial. Half of the 478 patients with OL will receive the intervention (sodium bicarbonate infusion) with preoperative normal saline infusion, and the other half will receive the standard of care (preoperative saline infusion) alone.

Study setting

We will conduct this study in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital located at the heart of Mbale Municipality, 214 km to the East of the capital city, Kampala. It is the main referral hospital, serving 14 districts in the Elgon zone, bordering western Kenya. This is a government run, not-for-profit, charge-free, 470-bed hospital with 52 maternity beds. The Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology has one consultant, two specialists, three medical officers and 21 Midwives. In terms of outputs, the labour and delivery suite is only second to the Mulago National Referral Hospital labour suite. Annually, about 12 000 childbirths occur in this hospital with a caesarean section rate of 35% and ~500 mothers have OL. The MOH has ranked it as the best performing Regional Referral Hospital in Uganda for the last 4 years.

Participants

This study will be carried out among patients with OL admitted to the labour suite in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital for emergency caesarean section during the period of the study. Either a medical officer or specialist on duty using the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) definition will make the diagnosis of OL. In the first stage of labour, she should have cervical dilatation >6 cm with ruptured membranes, adequate contractions lasting >4 hours with no change in cervical dilatation or delay in the second active stage of labour (nullipara >2 hours, multipara >1 hour) with adequate uterine contractions. In addition, any two of: the obvious signs of severe obstruction such as caput formation, severe moulding, Bandl’s ring, subconjunctival haemorrhages or an oedematous vulva.

We will include patients with OL carrying singleton, term pregnancies (≥37 weeks of gestation) in cephalic presentation. We will exclude patients with other obstetric emergencies such as antepartum haemorrhage, preeclampsia and eclampsia (defined as elevated blood pressure of at least 140/90 mm Hg, urine protein of at least 2+, any of the danger signs and fits), premature rupture of membranes and intrauterine fetal death. Patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, sickle cell disease, renal disease, liver disease and heart disease. We will also exclude those patients with hypokalemia (<3.3 mmol/L), hypocalcaemia (<8.2 mmol/L), hypernatraemia (>148 mmol/L) and alkalosis (bicarbonate >22 mmol/L) because they are more likely to develop adverse drug reactions.

Randomisation

An independent biostatician will generate a sequence of random numbers using the online randomisation service of www.sealedenvelope.com in permuted block sizes of four, six and eight. Based on this sequence, OL patients will be randomly allocated to either intervention or control arms in a 1:1 ratio. An independent pharmacist who is not involved in the recruitment of study participants, will conceal the randomisation sequence by preparing new labels with sequential numbers to be placed on identical study drug packages each containing five similar 10 mL glass vials without the original labels. After consent for inclusion is confirmed, a study nurse will take the next study drug package and administer its contents to the participant.

Intervention

The intervention will be a preoperative infusion of 50 mL of sodium bicarbonate 8.4% solution equivalent to 4.2 g or 50 mmol/L of bicarbonate (Martindale Pharma, Essex, UK) in 10 mL glass vials. The sodium bicarbonate will be administered intravenously as a bolus immediately after recruitment by trained research assistants who are all experienced midwives working in the labour suite, followed by 1.5 L of normal saline over the next hour.

Comparator

Participants in the control arm will receive a preoperative infusion of normal saline, which is part of the current standard of care. Fifty millilitres of sodium chloride 0.9% in identical 10 mL glass vials (AccuHealth Care, Gujarat, India) will be administered intravenously as a bolus immediately after recruitment by trained research assistants, who are all experienced midwives working in the labour suite, followed by 1.5 L normal saline over the next hour.

In addition, recruits will receive the standard preoperative care which includes preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis, at least 1.5 L of intravenous fluids preoperatively, bladder emptying, administration of oxygen and lying in left-lateral position.16

Measurements

The primary outcomes in this study will be the mean lactate levels in maternal capillary blood at 1 hour after the onset of study drug administration and in arterial cord blood within 1 min of birth. We will measure lactate at the bedside using a hand-held Lactate Pro2 device (Arkray Factory).

The secondary maternal outcomes will include myometrial lactate levels at caesarean section, maternal mortality up to 14 days postpartum. Other morbidities such as primary PPH, birth canal injuries, duration of admission, puerperal sepsis (persistent fever >38°C, chills and general malaise, pain in the lower abdomen, persistent bloody/pus discharge [lochia] from genital tract, which may have an unpleasant smell, tenderness on palpating the uterus uterine subinvolution, wound dehiscence/burst abdomen),16 fistulae and readmissions. Secondary perinatal outcomes will include mean lactate in venous cord blood, APGAR score, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), asphyxia, neonatal sepsis (irritability, poorly breast feeding, bulging anterior fontanelle)16 and perinatal death up to 7 days postpartum.

For the secondary safety outcomes, we will monitor for the following drug reactions throughout the period of the study. Frequent urge to urinate, continuing headache, continuing loss of appetite, mood or mental changes, muscle pain or twitching, nausea or vomiting, stomach crumps, slow breathing, swelling of feet or lower limbs, unpleasant taste, increased thirst, unusual tiredness or weakness, venous irritation, cellulitis and intravenous site pain.20–22

Sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics

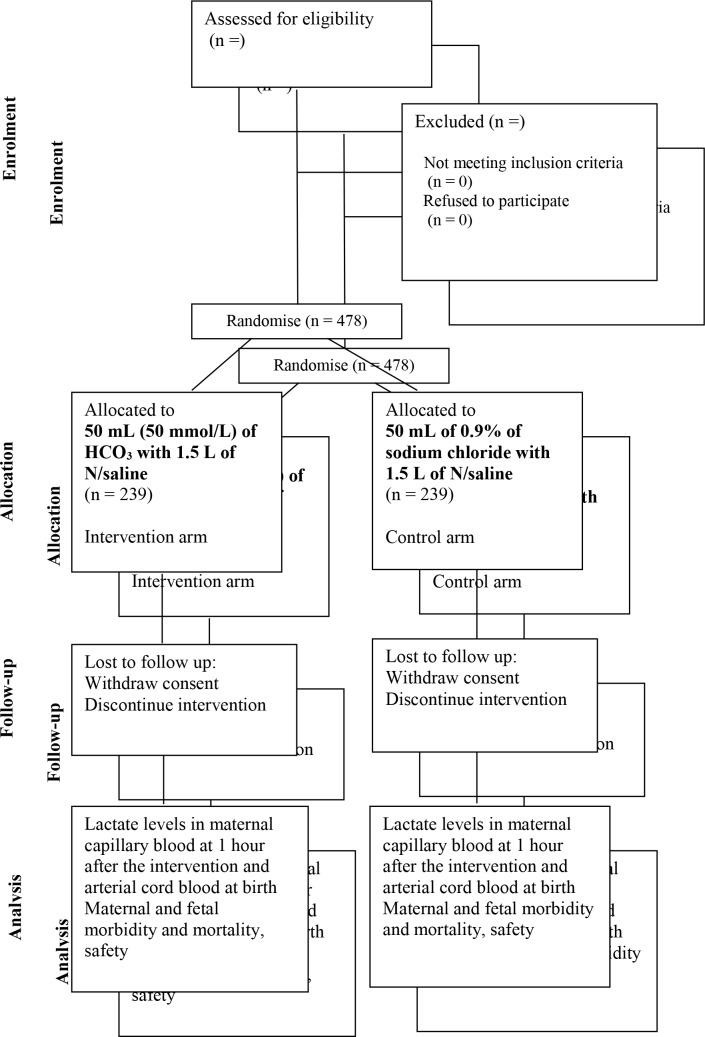

Using an interviewer administered questionnaire and available records (antenatal cards, facility registers and case report files), sociodemographic and clinical characteristics will be collected by trained research assistants. At baseline, five millilitres of blood will be collected in the appropriate vacutainers for a complete blood count, renal function tests, liver function tests and electrolytes. Ten millilitres of fresh urine will be collected in a sterile container for analysis. All these specimens will be delivered to MBN clinical laboratories within 1 hour of collection for analysis. Figure 1 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram for this study. We will follow-up patients for up to 14 days postpartum either by phone call if they are discharged or by direct visits if they are still admitted according to the current standard of care for patients with OL in Uganda.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participants in the trial.

Sample size and power calculation

Since the multiple testing in this study will be corrected for at analysis, we estimated the sample size to cater for that. The testing will take place c = two times, the final analysis will use a Bonferroni-Holm correction to adjust for multiplicity and the critical value will divide the α level by c.

To detect a Δ=15% difference in mean lactate levels between the intervention and control arms. Assuming an equal number of participants in each group, a two-sided significance level α of 0.05 for a 95% CI, a power (1−β) of 90%, an allowance of c = two multiple comparisons and a Bonferroni-Holm method for comparison of means, we used the formula, 23 and Open Epi24 to determine the sample size. Where and using standard normal tables.

The mean and SD of the maternal venous lactate at the end of second stage of labour is 2.6±1.0 mmol/L25 without any use of bicarbonate. To detect a difference of 15% (0.39 mmol/L) at 1 hour and assuming the same SD of ±1 in both arms, 326 participants will be required. Correcting for an attrition rate of 10%,14 gives a total sample size of 364.

The mean arterial umbilical cord blood lactate at 37 weeks of gestation is 4.3±1.9 mmol/L26 without any use of bicarbonate. In order to detect a difference of 15% (0.645 mmol/L) at birth and assuming the same SD of ±1.9 in both groups, 432 participants will be recruited. Correcting for an attrition rate of 10%14 gives a total sample size of 478. We therefore chose a sample size of 478 to provide adequate power for both hypotheses.

Data collection and management

Well-trained research assistants (RAs) will collect data using a pretested interviewer administered electronic questionnaire on password protected smart phones using the Open Data Kit software.27 To increase accuracy, the data will be triangulated with a review of relevant health facility records such as the antenatal cards, the maternity and theatre registers and the participants’ case notes. The questionnaire will be coded with checks for internal consistency. Data on sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory parameters will be collected at baseline, at 1 hour after onset of study drug administration for the primary maternal outcome, at the time of childbirth for the primary neonatal outcome and at 7 and 14 days postpartum for the secondary perinatal and maternal outcomes as summarised in table 1. The principal investigator (PI) will review the entries from the Google aggregate server every 24 hours to ensure data quality and completeness.

Table 1.

Summary of the study procedures and timelines

| Procedure | At admission (baseline) | 1 hour after onset of study drug administration | At birth | At 7 days postpartum | At 14 days postpartum |

| Assessment of eligibility | x | ||||

| Randomisation | x | ||||

| Data collection for baseline parameters | x | ||||

| Study drug administration | x | ||||

| Questionnaire administration | x | x | x | x | x |

| Data collection for primary outcome | x | x | |||

| Data collection for secondary outcome | x | x | x |

Statistical analysis

This will be conducted using STATA V.14 software or higher using the principle of ‘intention to treat’. Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise baseline characteristics of the study participants and assess if randomisation was successful. The primary maternal outcome will be the difference in capillary blood lactate levels at 1 hour after onset of study drug administration. The Bonferroni-Holm method28 29 will be used to compare the difference in means at baseline and 1 hour after onset of study drug administration both within and between each of the two arms.

For the primary fetal outcome of mean arterial cord blood lactate at birth, the Bonferroni-Holm method will be used to compare the mean lactate levels in the two arms within 1 min of childbirth.

The secondary outcomes will be reported as proportions in each of the two arms. Categorical variables will be compared using the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests. Potential confounders and effect modifiers unbalanced at baseline and associated with the outcome (p<0.05) will be adjusted for using multivariable linear or/and logistic regression. Proportions and the number needed to treat/number needed to harm will be reported for the secondary maternal and fetal outcomes.

We will do a subgroup analysis of patients admitted as referrals with a diagnosis of OL (to represent patients most likely to have neglected OL) to compare them with those who are diagnosed with OL within the referral hospital. A second subgroup analysis will be for those patients who give birth >2 hours after administration of the study drug, when we expect the effect of the intervention to have worn off.

Quality control

We will conduct a dry run for a period of 1 month before introducing the intervention. To facilitate the training of all the research assistants in the study protocol procedures, filling of study questionnaires using the open data kit (ODK) software,27 accurate measurement of lactate at the bedside using the Lactate Pro2 device and the ideal technique for collection of samples especially blood to avoid haemolysis. The MBN clinical laboratories are internationally accredited and they are involved in regular internal and external quality control checks.

The sponsor of this study (Makerere University) does not formally monitor studies to ensure compliance and adherence to the standard operating procedures of the study protocol. The PI will check each case report form on submission for completeness and undertake regular interviews with study staff and a sample of the study participants to check on the adherence. In addition, the regulatory bodies such as the Institutional review board (IRB), Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) and National Drug Authority also carry out regular scheduled and unscheduled spot checks to monitor adherence of the study to the approved protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

Participant safety

During the study, all the serious adverse events will be actively identified and reported to the IRB within 24 hours of occurrence. We will adopt and use the School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee reporting form. Only qualified health workers will be recruited and trained in the protocol to work as research assistants on this trial. The independent data monitoring committee will review unblinded data when one-third of the participants have been enrolled and followed up to completion and report to the sponsor of the study. If need arises such as patient safety, the study Steering Committee and the Independent data monitoring committee (IDMC) will request the independent study biostatistician to unblind the treatment allocation for a specific patient or group of patients without compromising the allocation concealment for the rest of the participants.

Dissemination plan

Results will be disseminated to the study participants through the local radio stations and local council community meetings at the village level. Findings will be shared with colleagues and administrators in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital/Busitema University Faculty of Health Sciences and the Uganda MOH through workshops and seminars. To reach the wider scientific community, the findings will be published in open access peer-reviewed journals and presented at both local and international conferences. The datasets will be provided free of charge by the primary author on request.

Patient and public involvement

The patients and public were not involved in the design and conceptualisation of this study.

Discussion

If the preoperative infusion of sodium bicarbonate is safe and effective in reducing maternal and fetal lactatemia (acidosis) among patients with OL, then the data from this trial will inform the design of future trials that will facilitate the inclusion of sodium bicarbonate infusion in the standard preoperative care for patients with OL in low-resource settings. Its adoption will help to mitigate adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with OL as a tertiary preventive measure for intrauterine maternal and fetal resuscitation. OL is still an important clinical and public health problem in low-resource settings because of the associated maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality caused by the accompanying electrolyte and metabolic changes. Therefore, identifying an effective, cheap, safe and readily available acid buffer like sodium bicarbonate might offer immense health benefits.

In OL, lactatemia might be a protective mechanism to prevent uterine rupture especially in the multiparous patients and fetal hypoxia by causing relaxation of the myometrium in order to improve fetal placental circulation.10–12 Therefore, reversal of lactic acidosis might result in stronger uterine contractions and increase the degree of fetal hypoxia or risk of uterine rupture especially if the surgical intervention is delayed. Thus, although this study will help us to understand whether 50 mmol of bicarbonate is effective at reversing lactic acidosis; further studies will be required to ascertain its effects on maternal and fetal morbidity.

In the body, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) rapidly disintegrates into sodium and bicarbonate ions and its effects wear off in 60–90 min. It does not cross the placenta, it is unknown if NaHCO3 is excreted in breast milk and its effects on lactation are unknown. Since we are administering a single low-dose preoperatively, we believe that it will have no effect on lactation. This will need further study in the future even if past studies have not reported any adverse effects.20–22

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the PI of the Survival Pluss Project and all his Coinvestigators for funding this work through a PhD fellowship awarded to me under Busitema University.

We thank Felix Wamono from the School of Statistics and planning for providing the statistical support on this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MWM conceptualised, designed, developed the protocol and drafted the manuscript. JKB, JNW, GN and AW all participated in the conceptualisation, design, development of the protocol and writing of the manuscript by providing critical review and refinement of the research idea as supervisors of my PhD studies. All the authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript for submission.

Funding: Survival Pluss project grant number UGA-13-0030 at Makerere University supported this work. Survival Pluss project is funded by The Norwegian Programme for Capacity Development in Higher Education and Research for Development (NORHED) under The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The protocol is approved by the Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (#REC REF 2017-103), the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS217ES) and the Mbale Regional Referral Research and Ethics Committee (MRRH-REC IN-COM 00/2018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. . National, regional, and global levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016;387:462–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. . Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e323–e333. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kadowa I. Ruptured uterus in rural Uganda: prevalence, predisposing factors and outcomes. Singapore Med J 2010;51:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neilson JP, Lavender T, Quenby S, et al. . Obstructed labour. Br Med Bull 2003;67:191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kabakyenga JK, Östergren PO, Turyakira E, et al. . Individual and health facility factors and the risk for obstructed labour and its adverse outcomes in south-western Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:73 10.1186/1471-2393-11-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usharani N, Bendigeri M. A study on clinical outcome of obstructed labour. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2017;6:439–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7. MOH. The Republic of Uganda Annual Health Sector Performance Report. 2017.

- 8. Barageine JK, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha JK, et al. . Risk factors for obstetric fistula in Western Uganda: a case control study. PLoS One 2014;9 10.1371/journal.pone.0112299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrison MS, Goldenberg RL. Cesarean section in sub-Saharan Africa. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 2016;2:6 10.1186/s40748-016-0033-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arrowsmith S, Kendrick A, Hanley JA, et al. . Myometrial physiology – time to translate? Exp Physiol 2014;99:495–502. 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.076216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quenby S, Pierce SJ, Brigham S, et al. . Dysfunctional labor and myometrial lactic acidosis. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:718–23. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000118306.82556.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wray S. Insights into the uterus. Exp Physiol 2007;92:621–31. 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.038125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Omo-Aghoja L, Maternal O-AL. Maternal and fetal Acid-base chemistry: a major determinant of perinatal outcome. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014;4:8–17. 10.4103/2141-9248.126602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiberg-Itzel E, Wray S, Åkerud H. A randomized controlled trial of a new treatment for labor dystocia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;31:1–8. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1339268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Markovic S, Fages A, Roussel T, et al. . Placental physiology monitored by hyperpolarized dynamic 13C magnetic resonance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E2429–E2436. 10.1073/pnas.1715175115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda Clinical Guidelines 2016. 2016;1142 http://health.go.ug/sites/default/files/Uganda Clinical Guidelines 2016_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dawood F, Dowswell T, Quenby S. Intravenous fluids for reducing the duration of labour in low risk nulliparous women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD007715 10.1002/14651858.CD007715.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaieski DF, Drumheller BC, Goyal M, et al. . Accuracy of handheld point-of-care fingertip lactate measurement in the Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med 2013;14:58–62. 10.5811/westjem.2011.5.6706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krustrup P, Ermidis G, Mohr M. Sodium bicarbonate intake improves high-intensity intermittent exercise performance in trained young men. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2015;12:25 10.1186/s12970-015-0087-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3697/smpc#UNDESIRABLE_EFFECTS (accessed 16 Jan 2019).

- 21. Sodium Bicarbonate. NaHCO3 - PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/sodium_bicarbonate#section=Top (accessed 29 Oct 2017).

- 22. Sodium Bicarbonate. https://www.glowm.com/resources/glowm/cd/pages/drugs/s014.html (accessed 16 Jan 2019).

- 23. Wittes J. Sample size calculations for randomized controlled trials. Epidemiol Rev 2002;24:39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sullivan KM, Dean A. On Academics. Public Health Rep 2009;124:471–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nordström L, Achanna S, Naka K, et al. . Fetal and maternal lactate increase during active second stage of labour. BJOG 2001;108:263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wiberg N, Källén K, Herbst A, et al. . Lactate concentration in umbilical cord blood is gestational age-dependent: a population-based study of 17 867 newborns. BJOG 2008;115:704–9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartung C, Anokwa Y, Brunette W, et al. . Open Data Kit: Tools to Build Information Services for Developing Regions. Proc Int Conf Inf Commun Technol Dev 2010:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen SY, Feng Z, Yi X. A general introduction to adjustment for multiple comparisons. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:1725–9. 10.21037/jtd.2017.05.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics Notes: Multiple significance test: Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995;310:170 All Papers/Other/Bland, Altman - 1994 - Statistics not. - Bland, Altman - 1994 - Statistics notes Matching.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.