Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence, degree of trust and usefulness of the online health information seeking source and identify associated factors in the adult population from the rural region of China.

Design

A cross-sectional population-based study.

Setting

A self-designed questionnaire study was conducted between May and June 2015 in four districts of Zhejiang Province.

Participants

652 adults aged ≥18 years (response rate: 82.8%).

Primary outcome measures

The prevalence, degree of trust and usefulness of online health information was the primary outcome. The associated factors were investigated by χ2 test.

Results

Only 34.8% of participants had faith in online health information; they still tended to select and trust a doctor which is the first choice for sources of health information. 36.7% of participants, being called ‘Internet users’, indicated that they had ever used the internet during the last 1 year. Among 239 internet users, 40.6% of them reported having sought health information via the internet. And 103 internet users responded that online health information was useful. Inferential analysis demonstrated that younger adults, individuals with higher education, people with a service-based tertiary industry career and excellent health status used online health information more often and had more faith in it (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Using the internet to access health information is uncommon in the rural residential adult population in Zhejiang, China. They still tend to seek and trust health information from a doctor. Internet as a source of health information should be encouraged.

Keywords: trust, internet, health information seeking, doctor

Strength and limitations in this study.

This study focused on health information seeking behaviours in rural residential adults.

This study would determine the influencing factors of online health information.

The main limitation of the study was that selection bias could exist due to migration by some younger adults.

Introduction

With the remarkable proliferation of internet and mobile technology, the internet becomes a potential source of health information. Until now, there have been many studies on the prevalence of internet health information seekers worldwide. According to the Pew internet and American Life Project, 35% of US adults turned to the internet for seeking health information.1 In Egypt, 55.4% of individuals considered the internet as the first source of health information.2 In addition, the determinants of internet health information seeking beheaviors had been done among different populations.3 While in China, where the population accounts for about 20% of the world’s population and rural residents are the majority, few studies have focused on internet access for health information in the rural residential population.

In recent decades, there has been a dramatic increase in internet users in China who have ever used the internet in the last 1 year. For instance, the thirty-third and forty-first China Statistical Reports on the development of the internet indicated that the number of internet users in China has increased from 618 million in December 2013 (45.8% of the population) to 772 million in December 2017 (55.8% of the population). Mobile users who have ever used mobile for access to the internet in the last 1 year have increased from 500 million to 753 million.4 5 With the rapid growth of the internet and the increasing use of the internet and mobile devices, whether the access to online health information measures up remains unknown.

This study aimed to investigate the preference, degree of trust and usefulness of online health information in the rural residential population in Zhejiang, China. By clearly indicating the characteristics of internet use for health purposes and its associated influencing factors, we intended to develop strategies for the dissemination of online health information.

Methods

Study design and outcomes

A cross-sectional study was conducted in four districts in Zhejiang Province, China from May to June 2015. The four inland districts were selected according to the economic levels. Higher economic level areas were Shaoxing (Xialv and Pingshui County) and Tongxiang (Zhou Quan and Cong Fu County), and lower economic level areas were Nanxun (Nan Xun and Jiu Guan county) and Tonglu (Jiu Xian and Bai Jiang County).

We calculated the sample size by stratified cluster sampling in three stages (county, villages, household). We assume an estimated 50% prevalence of use of online health information, considering a CI of 95%. We added 10% to compensate for possible losses and refusals. All participants were registered as rural residents, who had continuously resided in their location for at least 6 months. A total of 787 adults aged ≥18 years was recruited, and 135 were excluded because of missing information. Ultimately, 652 eligible participants completed the survey with the help of trained staff visiting their residence. After 1 day of the survey, the questionnaire was checked for completeness and accuracy.

The survey questionnaire was derived from a similar study conducted by LYU Qiaohong.6 Basic information included age (<45 years old, 45~60 years old, >60 years old), gender, education (primary school or lower, junior school, high or polytechnic school, college or higher), occupation (agriculture-based primary industry, manufacturing-based secondary industry, service-based tertiary industry, other including student or retired), living status (single living, non-single living) and health status (excellent, good, fair, poor). The Delphi method was used to ensure the validity of the questionnaire. The final questionnaire comprised seven questions probing the residents’ access to health information and their attitudes towards internet health information usage, including: degree of trust of health information seeking from doctors, family, SMS and internet (a lot, some, not at all, no comments), the frequency of using internet during the past year (often, sometimes, seldom, never), how often do they use the internet for seeking health information (daily, weekly, seldom, never); and the view about the usefulness of the internet health information (more, very, less, no, absolutely no).

Participant and public involvement

No participants were involved in the research design, and no participants were directly involved in the study. As the ultimate goal was to develop strategies for the dissemination of online health information, the findings will be disseminated to Chinese rural residents.

Statistical analysis

All the collected data were doubly entered into an EpiData V.3.1 software database by two staff, independently. Then we checked the accuracy, consistency and logicality of the data. Statistical Package for Social Sciences software was used for data processing and analysis. Social demographic information was analysed by descriptive statistics. The χ2 test was used for inferential analyses. The statistical hypothesis test level was 0.05.

Results

Of the 787 eligible participants, 652 completed the survey with a response rate of 82.8%, including 361 (55.4%) men and 291 (44.6%) women in four districts. The mean age of the participants was 54.3±11.9 years with a range of 17–88 years, while 81% of them were older than 45 years. Other basic characteristics of participants are listed in table 1. Most of the participants’ educational level was primary school or lower (48.2%); only 6.6% had college or higher education. Almost all participants were not living alone and more than half of them thought their health was excellent or good. On being asked whether they had used the internet during the last 12 months, 239 (36.7%) participants answered yes, of which 144 (60.3%) were men and 95 (39.7%) women. Unlike the age groups of total participants in the survey, most internet users were younger than 60 years old, with nearly half of them aged <45 years. Apart from age group, the composition of internet users’ education was also different.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all participants and internet users

| Values | All participants (n, %) | Internet users (n, %) |

| Total | 652 | 239 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 361 (55.4) | 144 (60.3) |

| Female | 291 (44.6) | 95 (39.7) |

| Age, years | ||

| <45 | 124 (19.0) | 108 (45.2) |

| 45~ | 258 (39.6) | 90 (37.7) |

| >60 | 270 (41.4) | 41 (17.2) |

| Education | ||

| Primary school or lower | 314 (48.2) | 38 (15.9) |

| Junior school | 204 (31.3) | 88 (36.8) |

| High school or polytechnic school | 91 (14.0) | 74 (31.0) |

| College or higher | 43 (6.6) | 39 (16.3) |

| Occupation | ||

| Agriculture-based primary industry | 425 (65.2) | 98 (41.0) |

| Manufacturing-based secondary industry | 141 (21.6) | 83 (34.7) |

| Service-based tertiary industry | 24 (3.7) | 20 (8.4) |

| Other (students or retired) | 62 (9.5) | 38 (15.9) |

| Marriage | ||

| Single living | 33 (5.1) | 14 (5.9) |

| Non-single living | 619 (94.9) | 225 (94.1) |

| Health status | ||

| Excellent | 54 (8.3) | 40 (16.7) |

| Good | 322 (49.4) | 145 (60.7) |

| Fair | 252 (38.7) | 52 (21.8) |

| Poor | 24 (3.7) | 2 (0.8) |

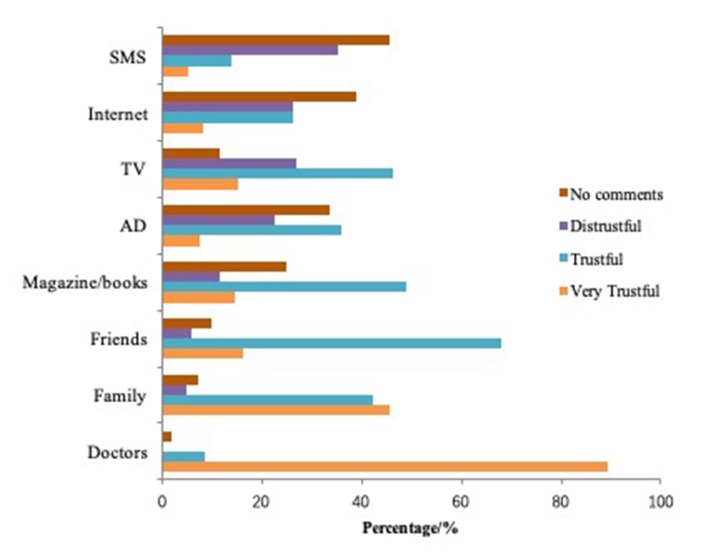

Figure 1 shows the degree of trust on online health information sources and other health information sources. From the figure, the most reliable health information source was the doctor rather than the internet.

Figure 1.

Degree of trust in various health information sources. AD, advertisement.

Table 2 further shows the reliability of health information sources the doctor and internet in all participants and internet users. Among 652 participants, 634 individuals were more likely to trust the doctor; similarly 235 internet users trusted the doctor. Only 34.8% of participants thought health information from internet was reliable, however, 60.9% of internet users had faith in online health information, and there were significant differences between all participants and internet users.

Table 2.

Degree of trust of health information source as the doctor and internet between all participants and internet users (n, %)

| Degree | Doctors* | Internet** | ||

| Participants | Internet users | Participants | Internet users | |

| A lot | 578 (89.2) | 210 (88.6) | 53 (8.4) | 38 (16.2) |

| Some | 56 (8.6) | 25 (10.5) | 166 (26.4) | 105 (44.7) |

| Not at all | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 166 (26.4) | 59 (25.1) |

| No comments | 12 (1.9) | 2 (0.8) | 244 (38.8) | 33 (14.0) |

| Total | 648 (100) | 237 (100) | 629 (100) | 235 (100) |

Note, the total number of participants was 652 and the total number of internet users was 239, the total numbers in table 2 had excluded the apparently wrong data.

*P>0.05

**P<0.001

As table 3 shows, 40.6% of internet users used the internet for health information during the past year. Of them, 7.1% reported using the internet daily for health information and 33.5% used it weekly for health information, while 48.1% reported rare usage and 11.3% never used the internet for health information.

Table 3.

Internet users’ online health information seeking behaviour

| Frequency of use | N (%) |

| Daily | 17 (7.1) |

| Weekly | 80 (33.5) |

| Seldom | 115 (48.1) |

| Never | 27 (11.3) |

| Total | 239 (100) |

Of 239 participants, 237 responded on the usefulness of internet health information (table 4). However, less than 50% people held the view that health information on the internet was useful.

Table 4.

Views about health information on the internet

| Usefulness of the internet source | N (%) |

| More | 13 (5.5) |

| Very | 90 (38.0) |

| Less | 105 (44.3) |

| No | 27 (11.4) |

| Absolutely no | 2 (0.8) |

| Total | 237 (100) |

As seen in table 5, there were significant differences between age, educational level and occupation group (p<0.001) and the trust, the frequency and the usefulness of the internet health information source. Participants, who were younger than 45 years, reported using the internet for health information more often and thought the health information from the internet was more reliable.

Table 5.

Comparison of different values for the trust, frequency and usefulness of the internet health information source

| Values | Total | Trust | Frequency | Usefulness | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 361 | 127 (35.2) | 53 (14.7) | 60 (16.6) | |

| Female | 291 | 92 (31.6) | 44 (15.1) | 43 (14.8) | |

| χ2 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.41 | ||

| P values | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.59 | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| <45 | 124 | 75 (60.5) | 49 (39.5) | 47 (37.9) | |

| 45~ | 258 | 75 (29.1) | 30 (11.6) | 34 (13.2) | |

| >60 | 270 | 69 (25.6) | 18 (6.7) | 22 (8.1) | |

| χ2 | 50.38 | 75.97 | 58.76 | ||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary school or lower | 314 | 58 (18.5) | 15 (4.8) | 13 (4.1) | |

| Junior school | 204 | 73 (35.8) | 29 (14.2) | 33 (16.2) | |

| High school or polytechnic school | 91 | 57 (62.6) | 32 (35.2) | 35 (38.5) | |

| College or higher | 43 | 31 (72.1) | 21 (48.8) | 22 (51.2) | |

| χ2 | 95.61 | 94.10 | 107.67 | ||

| P values | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Agriculture-based primary industry | 425 | 105 (24.7) | 31 (7.3) | 37 (8.7) | |

| Manufacturing-based secondary industry | 141 | 74 (52.5) | 36 (25.5) | 37 (26.2) | |

| Service-based tertiary industry | 24 | 14 (58.3) | 15 (62.5) | 12 (50.0) | |

| Other (students or retired) | 62 | 26 (41.9) | 15 (24.2) | 17 (27.4) | |

| χ2 | 46.12 | 79.17 | 55.03 | ||

| P values | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Marriage | |||||

| Single living | 33 | 13 (39.4) | 6 (18.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Non-single living | 619 | 206 (33.3) | 91 (14.7) | 95 (15.3) | |

| χ2 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 1.86 | ||

| P values | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.22 | ||

| Health status | |||||

| Excellent | 54 | 28 (51.9) | 18 (33.3) | 16 (29.6) | |

| Good | 322 | 130 (40.4) | 65 (20.2) | 69 (21.4) | |

| Fair | 252 | 58 (23.0) | 13 (5.2) | 18 (7.1) | |

| Poor | 24 | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | |

| χ2 | 32.13 | 42.66 | 34.14 | ||

| P values | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Principal results

There were 36.7% respondents who indicated that they used the internet during the past 1 year and 40.6% of internet users reported that they had sought health information via the internet; this was more than 7.8% of respondents who had reported online health information seeking history by Lee et al.7 This could be as a result of the higher socioeconomic status of Zhejiang Province in China and the relatively lower price for internet access. In addition, internet access through smartphone was considered in this study.

In addition, almost all the participants reported the doctor rather than internet to be the first and the most reliable source of health information, consistent with the findings of Marrie et al.8 The possible reason may be that most of the respondents in our study were rural residents older than 45 years, which is consistent with our national reports. According to the forty-first China Statistical Report on Internet Development,5 most of the internet users in China were 20–39 years old and were urban residents. Rural internet users accounted for only 27.0%. Hence, we could suggest that the majority of rural residents older than 45 years were not internet users. Through the report,5 the two most common reasons for being non-users of the internet were that they lacked internet skills, and they were unable to understand ‘Pin Yin’ in Chinese. ‘Pin Yin’ is important to search information from the internet. In addition, it reported that free internet training and internet equipment such as ‘Voice Input Method’ could promote internet use.

As for the internet health information, internet users other than all the rural residents tend to trust it. This suggests that Chinese rural residents do not believe in online health information yet. Although most of them did not choose the internet first, more internet users thought that the online health information was useful. And the finding was more commonly seen in younger adults, individuals with higher educational level, people from the service-based tertiary industry and people with excellent health. The results were similar to those from another study in Japan.9–18 They also observed that the prevalence of internet use for acquiring health-related information was low. And the internet was used for acquiring health-related information primarily by younger people and people with higher educational levels. This was because older people and those with a lower educational level were unfamiliar with the internet and had barriers to access health-related information. Hence, the effective solution was to train them to be familiar with the internet and make internet access easier. In China, with the rapid ageing of the Chinese population, the number of residents who are familiar with the internet and free of barriers to internet access would increase. However, the reality that most rural residents trust doctors would not change rapidly. And they believe more in doctors in big-city top-flight hospitals. As the numbers of doctors in big-city top-flight hospitals are relatively limited, they often queue overnight just to get a consultation lasting a few minutes,19 and they often have difficulty gaining access to appropriate healthcare.20 Hence, the internet hospital emerged in China. Internet hospital refers to a new approach to provide health services by qualified doctors in top hospitals through internet technology.21 As internet hospital overcomes geographical obstacles and shatters time barriers, it could meet their needs with the doctor and internet simultaneously. In China, the population of internet medical services users was 194.8 million in 2016, accounting for 26.6% of all internet users.22 Therefore, it could address the difficulty of waiting times by providing Chinese patients online access to skilled doctors.23 Up to now, the internet hospital is still a medical development model, whose function is similar with traditional ones, including medical information, electronic health records, disease risk assessment, disease/health counselling, electronic prescription, telemedicine and health education.24 Its final model should be a smart hospital, which entails providing big data, artificial intelligence and precision medicine. Consequently, corresponding policies should be ensured.

Limitations

This study has several potential limitations. First, there is a bias with regards to age as the study was conducted between May and June, when most of the younger adults migrate to urban areas for work or learning. This could be solved through flexible research, though some individuals may return home at irregular times while most of them would indeed return home at the end of the year. Second, we also failed to obtain data on eHealth literacy, patterns of internet users and the contents of health information, all of which may affect online health information seeking behaviour. All of them need further study through improved questionnaires and considering more factors. This sample is not a general Chinese sample, but may suggest trends taking place in rural regions of China. Third, we forgot to include the total time the participants surfed the internet and the time they spent seeking health information. We will explore this further.

Conclusions

Rural residents in Zhejiang Province are less likely to use internet for health information. They still tend to seek health information from doctors and trust the doctor. The internet as a source of health information should be encouraged. Luckily, among internet users, more than half would like to seek and trust health information through the internet. Younger adults, people with higher educational levels, people from the service-based tertiary industry and people with excellent health status are more likely to access online health information. Free internet training and easier access to the internet should be provided to older adults, especial those with primary school or lower education. In addition, internet hospitals could provide health information from qualified doctors through the internet. Of course, more policies should be ensured for the quality and management of internet hospital. Further, eHealth literacy and the outcomes (eg, health-related abilities and behaviours) of online health information sources should be taken into account in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the centers of disease control and prevention from four districts of Shaoxing, Nanxun, Tonglu and Tongxiang.

Footnotes

Contributors: YQ conducted the conception and design of research, analysed the data, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. WR, YL and PY contributed to the revision of the manuscript. JR had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Scientific and Technological Major Project of China (2017ZX10105001) and Clinical Research Project of Zhejiang Medical Association (2017ZYC-A11).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Fox S, Duggan M. Pew research center. Health online. 2013. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/ (accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 2. Ghweeba M, Lindenmeyer A, Shishi S, et al. What predicts online health information-seeking behavior among egyptian adults? A cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e216 10.2196/jmir.6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumann E, Czerwinski F, Reifegerste D. Gender-Specific Determinants and Patterns of Online Health Information Seeking: Results From a Representative German Health Survey. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e92 10.2196/jmir.6668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. China Internet Network Information Center. The 33rd china statistical report on internet development. 2013. http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201403/P020140305346585959798.pdf (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 5. China Internet Network Information Center. The 41st china statistical report on internet development. 2018. http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201803/P020180305409870339136.pdf (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 6. Qiaohong LYU, Shuiyang XU, Qingqing WU, et al. Study the current state about chronic disease information acquisition and new media utilization of residents in Zhejiang Province. Chinese Journal of Health Education 2014;30:976–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee YJ, Boden-Albala B, Jia H, et al. The association between online health information-seeking behaviors and health behaviors among hispanics in new york city: A community-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e261 10.2196/jmir.4368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marrie RA, Salter AR, Tyry T, et al. Preferred sources of health information in persons with multiple sclerosis: degree of trust and information sought. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e67 10.2196/jmir.2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takahashi Y, Ohura T, Ishizaki T, et al. Internet use for health-related information via personal computers and cell phones in Japan: a cross-sectional population-based survey. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e110 10.2196/jmir.1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zulman DM, Kirch M, Zheng K, et al. Trust in the internet as a health resource among older adults: analysis of data from a nationally representative survey. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e19 10.2196/jmir.1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sheng X, Simpson PM. Health care information seeking and seniors: determinants of Internet use. Health Mark Q 2015;32 96–112. 10.1080/07359683.2015.1000758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silver MP. Patient perspectives on online health information and communication with doctors: a qualitative study of patients 50 years old and over. J Med Internet Res 2015;17 e19 10.2196/jmir.3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chung JE. Patient-provider discussion of online health information: results from the 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Commun 2013;18 627–48. 10.1080/10810730.2012.743628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller LM, Bell RA. Online health information seeking: the influence of age, information trustworthiness, and search challenges. J Aging Health 2012;24 525–41. 10.1177/0898264311428167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaudhuri S, Le T, White C, et al. Examining health information-seeking behaviors of older adults. Comput Inform Nurs 2013;31 547–53. 10.1097/01.NCN.0000432131.92020.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ye Y. Correlates of consumer trust in online health information: findings from the health information national trends survey. J Health Commun 2011;16 34–49. 10.1080/10810730.2010.529491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwon JH, Kye SY, Park EY, et al. What predicts the trust of online health information?. Epidemiol Health 2015;37:e2015030 10.4178/epih/e2015030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Medlock S, Eslami S, Askari M, et al. Health information-seeking behavior of seniors who use the Internet: a survey. J Med Internet Res 2015;17 e10 10.2196/jmir.3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. IFENG. Phoenix information: why is it expensive and difficult to see a doctor in China?. URL 2016. http://news.ifeng.com/a/20160308/47743822_0.shtml (Accessed 13 Mar 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yip W, Hsiao W. Harnessing the privatisation of China’s fragmented health-care delivery. Lancet 2014;384:805–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61120-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qiu Y, Liu Y, Ren W, et al. Internet-based and mobile-based general practice: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e266 10.2196/jmir.8378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. CAC. The 39th China internet development statistics report URL. 2017. http://www.cac.gov.cn/2017-01/22/c_1120352022.htm (Accessed 13 Mar 2018).

- 23. Xie X, Zhou W, Lin L, et al. Internet hospitals in china: Cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e239 10.2196/jmir.7854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jing S. China daily. Healthcare just a click away. 2016. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/tech/2016-11/18/content_27415845.htm (Accessed 13 Mar 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.