Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect, on birth weight and birth weight centile, of use of the PrenaBelt, a maternal positional therapy device, during sleep in the home setting throughout the third trimester of pregnancy.

Design

A double-blind, sham-controlled, randomised clinical trial.

Setting

Conducted from September 2015 to May 2016, at a single, tertiary-level centre in Accra, Ghana.

Participants

Two-hundred participants entered the study. One-hundred-eighty-one participants completed the study. Participants were women, 18 to 35 years of age, with low-risk, singleton, pregnancies in their third-trimester, with body mass index <35 kg/m2 at the first antenatal appointment for the index pregnancy and without known foetal abnormalities, pregnancy complications or medical conditions complicating sleep.

Interventions

Participants were randomised by computer-generated, one-to-one, simple randomisation to receive either the PrenaBelt or sham-PrenaBelt. Participants were instructed to wear their assigned device to sleep every night for the remainder of their pregnancy (approximately 12 weeks in total) and were provided a sleep diary to track their use. Allocation concealment was by unmarked, security-tinted, sealed envelopes. Participants and the outcomes assessor were blinded to allocation.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were birth weight and birth weight centile. Secondary outcomes included adherence to using the assigned device nightly, sleeping position, pregnancy outcomes and feedback from participants and maternity personnel.

Results

One-hundred-sixty-seven participants were included in the primary analysis. The adherence to using the assigned device nightly was 56%. The mean ±SD birth weight in the PrenaBelt group (n=83) was 3191g±483 and in the sham-PrenaBelt group (n=84) was 3081g±484 (difference 110 g, 95% CI −38 to 258, p=0.14). The median (IQR) customised birth weight centile in the PrenaBelt group was 43% (18 to 67) and in the sham-PrenaBelt group was 31% (14 to 58) (difference 7%, 95% CI −2 to 17, p=0.11).

Conclusions

The PrenaBelt did not have a statistically significant effect on birth weight or birth weight centile in comparison to the sham-PrenaBelt.

Trial registration number

Keywords: obstetrics, fetal medicine, maternal medicine, stillbirth, positional therapy, low birth weight

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A double-blind, sham-controlled, randomised clinical trial.

The first to investigate longitudinal use of positional therapy in pregnancy in the home setting.

Results may not be generalisable to pregnant women with medical or pregnancy complications, non-Ghanaian ethnicity or living in other parts of the world.

Determination of adherence to device use was largely subjective, relying mostly on participants’ self-reports.

May be underpowered to detect a clinically meaningful difference.

Introduction

Background

Stillbirth (SB; a baby born with no signs of life at or after 28 weeks' gestation) and low birth weight (LBW; weight less than 2500 grams at birth), two devastating complications of pregnancy, disproportionately impact low- and middle-income countries.1–3 Five recent studies have demonstrated an association between maternal supine sleeping position in late pregnancy and risk of third trimester SB (between 28 and 40 completed weeks’ gestation)4–8 and LBW.4 The authors were first to demonstrate that supine sleep during pregnancy is associated with SB via a mediating effect of LBW in an African population.4 The population attributable risk of supine sleep for SB is reported between 3.7% and 26%,4 6–8 suggesting that a significant proportion of third trimester SB could be averted if supine sleep was avoided. While several major risk factors for SB and LBW are not amenable to intervention during the course of the pregnancy (eg, elevated BMI, advanced maternal age), recent studies suggest that maternal sleep position can be modified.9 10 This has particular relevance given that pregnant women spend between 17% to 25% of their sleep time supine in the third trimester.11–13

The contribution of supine sleep to LBW and SB is biologically plausible via aortocaval compression by the gravid uterus when supine, which results in reduced maternal cardiac output, maternal aortic blood flow, placental perfusion and foetal oxygen saturation.14–31 The supine position also exacerbates sleep-disordered breathing (SDB),32 33 which has been linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes.34–36 In persons with mild- to moderate-SDB, the majority experience most of their breathing abnormalities while supine.37Positional therapy (PT) is a simple, safe and effective treatment that helps these individuals maintain a lateral position while sleeping, thereby significantly reducing or eliminating their breathing abnormalities.37 38 However, among persons with SDB, issues with long-term adherence to PT have been documented.38 Drawing on the concept of PT for SDB, the authors designed a PT device for pregnant women called ‘PrenaBelt’ to minimise supine sleep (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PrenaBelt.

Objectives

The primary objective was to determine the effect, on birth weight and customised birth weight centile, of use of the PrenaBelt during sleep in the home setting throughout the third trimester of pregnancy in comparison with a sham-PrenaBelt. Secondary objectives were to: evaluate participant adherence, assess the effectiveness of the PrenaBelt in reducing time sleeping supine, collect participant feedback on the PrenaBelt and evaluate the feasibility of introducing the PrenaBelt to third trimester pregnant women by maternity personnel at an antenatal care clinic in Ghana.

Methods

Trial design

A single-centre, double-blind, randomised (one-to-one), sham-controlled clinical trial. After trial commencement, three protocol amendments occurred: birth weight centile was added as a trial outcome, feedback was inadvertently elicited from some participants in the sham group and a subgroup analysis of the effect of adherence on the primary outcome was specified.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question or outcome measures, design of the study, recruitment process or conduct of the study. There was no formal plan to disseminate the results to the participants.

Participants

Participants were recruited by maternity personnel when presenting for antenatal care at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH) – a tertiary-level hospital in Accra, Ghana, with over 10 000 newborns delivered annually. The KBTH is affiliated with the University of Ghana and is the leading national referral centre. Accra is the capital of Ghana and has an urban population of approximately 2.3 million. Patients expressing interest in the study were screened for eligibility.

Participants were eligible if they had a low-risk singleton pregnancy, were ≥18 years of age, entering the third trimester of pregnancy (range 26 to 30 weeks’ gestational age), residing in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area or area served by the KBTH and fluent in either English, Twi or Ga. Exclusion criteria included body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2 at the first antenatal appointment, obstetrical conditions (chronic or gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, diabetes, intra-uterine growth restriction), sleep complicated by any medical conditions (known obstructive sleep apnoea, known to get <4 hours of sleep per night due to insomnia, musculoskeletal disorder that prevents sleeping on the side), multiple pregnancy, known foetal-abnormality and advanced maternal age (>35 years old).

All participants in the trial gave written (or verbal, thumbprint and witnessed if illiterate) informed consent, which was endorsed by the participant’s spouse where applicable. This trial was approved and monitored by the Ghana Food and Drugs Authority (Accra, Ghana; Clinical Trial Certificate FDA/CT/152), the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research Institutional Review Board (Accra, Ghana; CPN 069/14–15) and the IWK Health Centre Research Ethics Board (Halifax, Canada; Project No. 1019318). This study had a local independent trial monitor. There was no independent data monitoring committee.

Interventions

Each participant was instructed to use her assigned device (PrenaBelt or sham-PrenaBelt) every night for the remainder of her pregnancy (approximately 12 weeks) and was provided a sleep diary and pen to track use.

The PrenaBelt is worn at the level of the waist and has two back pockets each containing two rigid, hollow, polyethylene balls held securely in place by a foam insert (figure 1.). The theoretical mechanism of the PrenaBelt is based on the tennis-ball technique of positional therapy39–41: when supine, the balls apply pressure points across the user’s lower back, prompting her to reposition herself in a lateral position to maintain comfort. The sham-PrenaBelt was identical in appearance, materials and construction to the PrenaBelt, but had soft foam balls instead of firm plastic balls and did not have foam inserts. A body position sensor (BPS) – a commercially available three-axis accelerometer (MSR Electronics GmbH, Henggart, Switzerland) – was incorporated into a subset of the devices (hereinafter referred to as the ‘BPS cohort’) (figure 2).

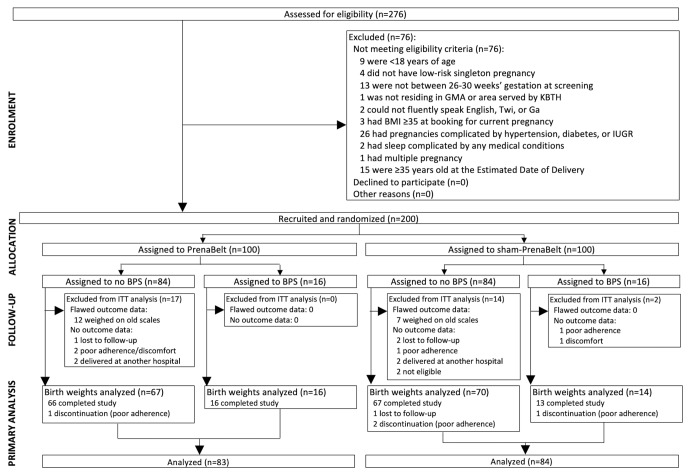

Figure 2.

Enrolment, allocation and analysis of trial participants. BMI, body mass index; BPS, body position sensor; GMA, Greater Accra Metropolitan Area; KBTH, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital; ITT=intention-to-treat; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Participants underwent an enrolment interview to elicit age, gestational age, gravidity, parity, education level, family income, current and pre-pregnancy BMI, nightly sleep duration, current and pre-pregnancy body position at sleep onset and waking, part of the bed the participant sleeps on, pillow use, presence of a bed partner, use of an insecticide treated bed net, participant snoring and past medical conditions.

During recruitment, participants were informed about the reason for the study, that is, recent studies have shown an association between supine sleep and stillbirth and low birth weight; however, the participants were not instructed to avoid or prefer any given sleeping position. Maternity personnel conducted introduction sessions to teach each participant how to use the device, practice trying it on and experience how it feels when lying down. Participants were instructed not to share their device with anyone. Participants were informed that it may take several nights to adjust to sleeping with the device and that they may discontinue use at any time. Participants were instructed to return to KBTH for their regular antenatal care (fortnightly from 28 to 36 weeks’ gestation then weekly until delivery) and labour/delivery. During antenatal care, each participant briefly met with maternity personnel who inquired regarding her willingness to continue participating in the study, continued eligibility, experience of any adverse effects and to remind her to return her device and sleep diary at labour/delivery.

After labour/delivery, participants in the treatment (PrenaBelt) group gave feedback on the PrenaBelt.

Outcomes

The primary outcome, birth weight, was measured using a Detecto newborn scale (Webb City, USA) and documented in the participant’s hospital folder immediately after delivery by a midwife who was not a part of the study team and was not aware of the treatment allocation. Birth weight was subsequently abstracted by the blinded outcomes assessor (MO).

Adherence to using the assigned device (percentage of nights used relative to the total number of nights in the trial) was determined from the sleep diary (all participants) and the BPS (BPS cohort). For the BPS cohort, the raw accelerometer data was resolved to yield body position during device use. Pregnancy outcomes were abstracted from the hospital folders by the blinded outcomes assessor: mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, sex, stillbirth and any obstetrical diagnosis during labour/delivery. Feedback from participants in the treatment group was collected by maternity personnel: experience understanding and learning to use the PrenaBelt, general use pattern, number of nights of use per week, deterrents to use, other uses, perception of effect on sleep position, quality, quantity and her level of satisfaction, comfort and intention to use the PrenaBelt in a future pregnancy on a 10-point Likert scale (10 out of 10=most favourable response, 1 out of 10=least). At completion of recruitment, the maternity personnel completing the device introduction sessions completed a questionnaire eliciting their training level, professional experience and perspectives on session duration, delivery method and challenges.

Birth weight centile was calculated using the gestation-related optimal weight (GROW) software,42 43 which accounts for the main non-pathological factors affecting birth weight (gestational age, maternal height, maternal weight at booking, parity, ethnicity and sex of the neonate) and, as such, enables delineation between constitutional and pathological smallness and more accurate detection of pregnancies at increased risk for adverse outcomes.44 45 This was an additional trial outcome specified after trial commencement. Small for gestational age was defined as a GROW birth weight centile less than 10%.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was performed using the ‘PS power and sample size programme’ (V.3.0). Based on a previous study in Ghana by members of our team, we expected a 300 g difference in birth weight between the treatment and sham groups and a SD (pooled) of 643 g.4 For a power (β) of 0.80 and type I error probability (α) of 0.05, we arrived at a sample size of 146 (73 per group) to reject the null hypothesis that the mean birth weight of the treatment and sham groups were equal. Based on an estimated lost-to-follow-up of 20% to 30%, target enrolment was 200 participants (100 per group).

Randomisation

Each participant was randomly allocated to either the treatment or sham group. The allocation sequence was concealed via unmarked, security-tinted, sealed envelopes and generated by a computerised (R statistical software, V.3.2.0),46 one-to-one, simple randomisation scheme by an independent statistician (MB) not involved in any study activities in Ghana. An envelope was drawn in sequence by the recruiters, opened and the participant’s name and birth date were recorded on an enclosed allocation form.

Blinding

Participants remained blinded to the allocation until after study completion. Efforts to ensure that each participant did not know what the alternate device looked or felt like included conducting separate introduction sessions for each group and ensuring no balls or foam inserts were in the device (so it was configured neither as a PrenaBelt nor sham-PrenaBelt) during demonstrations.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed in the R statistical software package (V.3.2.4).46 Data was double-entered (JW, SM) from scanned originals into Microsoft Excel files, double-entry checked (AK) using the Spreadsheet Inquire add-in and scrubbed prior to the final analysis (AK).

Primary, secondary and adverse event outcomes were compared between groups. Adverse events (AEs) were classified as ‘common AEs’ if they occurred in ≥1% of the participants in the treatment group. For continuous variables, normality was assessed using Q-Q plots and the Anderson-Darling test. T-tests were used for normally-distributed data and Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normal distributions. All statistical tests were two-sided. Dichotomous and categorical data was analysed using Fisher’s exact test. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant and CI of 95% were used.

Results

Between September 2015 and March 2016, 276 women were assessed for eligibility (figure 2). Seventy-six (28%) did not meet the eligibility criteria – we did not collect any data from them. When 200 participants were randomised (n=100 per group), the target enrolment was reached and recruitment stopped. After randomisation, 14 (7%) – five treatments and nine shams – were excluded from the all analyses because we lacked outcome data for them. Of these 14, five had dropped out due to poor adherence and/or discomfort, three were lost to follow-up, four had delivered at another hospital and two were excluded after it was discovered that they had been mistakenly enroled (one had not disclosed a pre-existing obstetrical complication, one was enrolled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to incorrect pregnancy dating). Further, 19 – 12 treatments and seven shams – delivering on or before 30 November, 2015, were excluded from the primary analysis (birth weight and GROW centile) and two secondary analyses that are dependent on birth weight (frequency of low birth weight and small for gestational age) because their birth weight data were flawed (their newborns were weighed on different newborn scales – analogue scales on the KBTH labour wards were replaced with new digital scales on 31 November, 2015). Thus, 167 participants (including four dropouts and one lost to follow-up) – 83 treatments and 84 shams – were included in the primary analysis, which was by intention to treat. The newborns included in the primary analysis were born from 31 November, 2015, through 13 May, 2016.

For those not completing the trial (n=19), there was no difference in time-before-discontinuation of participation between intervention groups (data not shown). See online supplementary file 1 for baseline characteristics of the participants included in the primary analysis (n=167) and those excluded (n=33) per randomised group.

bmjopen-2018-022981supp001.pdf (73.7KB, pdf)

Sample characteristics

Baseline demographical, obstetrical and previous sleep habit characteristics of the 167 participants included in the primary analysis are shown in table 1 per randomised group. The median age was 29 years and gestational age at recruitment was 28 weeks. The majority of participants were gravida 2 or greater and, hence, para 1 or greater. The majority had tertiary-level education. In the week previous to recruitment, left was the most common sleep onset and waking position, while prone was the most common when not pregnant. The majority of the participants slept with a pillow under their head and had a bed partner. The only statistically significant difference between the trial groups was nightly sleep duration.

Table 1.

Baseline demographical, obstetrical and sleep habit characteristics for participants included in the primary analysis

| Treatment (n=83) | Sham (n=84) | |

| Age (years) | 29 (27 to 31) | 29 (28 to 32) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 28.0 (26.4 to 28.2) | 28.0 (27.0 to 29.0) |

| Gravidity | ||

| 1 | 21 (25%) | 33 (39%) |

| ≥2 | 62 (75%) | 51 (61%) |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 30 (36%) | 40 (48%) |

| ≥1 | 53 (64%) | 44 (52%) |

| Education level | ||

| Tertiary | 51 (61%) | 50 (60%) |

| Vocational | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Senior high | 15 (18%) | 26 (33%) |

| Junior high | 12 (14%) | 5 (7%) |

| Primary | 3 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Undisclosed | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Household income (cedis/month) | 1200 (500 to 2500) [8] | 1400 (600 to 2500) [3] |

| Current BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9±4.2 [2] | 28.8±4.3 [2] |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1±4.1 [2] | 26.2±4.0 [3] |

| Nightly sleep duration (hours)* | 7.8±1.3 [1] | 8.2±1.3 |

| In the last week, usual | ||

| Sleep onset positions | ||

| Left | 42 (51%) | 48 (57%) |

| Supine | 12 (14%) | 10 (12%) |

| Right | 33 (40%) | 29 (34%) |

| Prone | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Waking positions | ||

| Left | 30 (36%) | 33 (39%) |

| Supine | 22 (27%) | 18 (21%) |

| Right | 27 (33%) | 34 (40%) |

| Prone | 4 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

| When not pregnant, usual | ||

| Sleep onset positions: | ||

| Left | 6 (7%) | 8 (10%) |

| Supine | 25 (30%) | 28 (33%) |

| Right | 10 (12%) | 9 (11%) |

| Prone | 43 (52%) | 40 (48%) |

| Waking positions | ||

| Left | 12 (14%) | 10 (12%) |

| Supine | 25 (30%) | 33 (39%) |

| Right | 15 (18%) | 14 (17%) |

| Prone | 33 (40%) | 27 (32%) |

| Part of bed sleeps on | ||

| Left | 42 (51%) | 34 (40%) |

| Right | 30 (36%) | 36 (43%) |

| Centre | 12 (14%) | 12 (14%) |

| Pillow use | ||

| None | 3 (4%) | 6 (7%) |

| Under head | 75 (90%) | 75 (89%) |

| Between knees | 7 (8%) | 5 (6%) |

| Under tummy | 4 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Behind back | 4 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Pregnancy pillow | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other (under feet or legs) | 2 (2%) | 6 (7%) |

| Sleeps with bed partner | 65 (78%) | 65 (77%) [2] |

| Insecticide treated bed net | 19 (23%) [1] | 19 (23%) [2] |

| Snores ≥3 nights per week | 10 (12%) [1] | 8 (10%) [3] |

| Past medical conditions† | 4 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean ±SD. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented as median (IQR). Count data are presented as frequency (%). Percentages for responses to some questions may add to greater than 100% because some participants checked more than one box in response to a question, eg, for sleep onset position in the last week, some responded ‘left’ and ‘right’. For the same reason, some count data may add up to more than the number of participants in the randomised group.

Square brackets [number] indicate that this number of participants did not disclose this data. If there are no square brackets, there are no missing data.

Average currency exchange rate for recruitment period: 1 USD=3.84 Cedis.

*Indicates a statistically significant difference between groups for these characteristics.

†Specifically, participants were asked about ‘intrauterine growth restriction, diabetes (gestational or not), hypertension (pre-eclampsia, gestational, chronic) or other medical conditions (please specify)’.

BMI, body mass index.

Primary outcome

The birth weight and GROW centile were higher by 110 grams and 7%, respectively, in the PrenaBelt group; however, this did not reach statistical significance on an unadjusted analysis (table 2) nor a multivariate linear regression controlling for the only difference in baseline characteristics between groups, that is, self-reported sleep duration (see online supplementary file 2).

Table 2.

Primary outcome: birth weight and GROW centile

| Treatment (n=83) | Sham (n=84) | Treatment – sham Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Birth weight (g) | 3191±483 | 3081±484 | 110* (−38 to 258) | 0.14 |

| GROW centile (%) | 43 (18 to 67) | 31 (14 to 58) | 7† (−2 to 17) | 0.11 |

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean ±SD. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented as median (IQR).

*Welch two sample t-test.

†Wilcoxon rank sum test.

GROW centile, Gestation Related Optimal Weight customised birth weight centile.

bmjopen-2018-022981supp002.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)

Secondary Outcomes

One-hundred-sixty participants (79 treatments, 81 shams) completed and returned the sleep diary (table 3). Overall adherence was 56%. There was no difference in adherence to using the assigned device between groups. For a subgroup analysis of the effect of adherence on the primary outcome, see online supplementary file 3 – the only statistically significant finding was that for the subgroup of participants with 50% or greater adherence (n=80), each 1% increase in adherence conferred a 0.5% increase in the GROW centile (p=0.046) independent of intervention group.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes: participant adherence per sleep diary

| Treatment (n=79) |

Sham (n=81) |

Treatment – sham Difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Number of nights of use | 42±21 | 43±22 | −1.4 (-8.0 to 5.2) | 0.67 |

| Number of days in trial | 76±16 | 75±17 | 1.3 (-4.0 to 6.5) | 0.63 |

| Adherence (%) | 55±27 | 58±26 | −2 (−11 to 6) | 0.57 |

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean ±SD and Welch’s two sample t-test is used to test for differences.

bmjopen-2018-022981supp003.pdf (48.2KB, pdf)

Pregnancy outcome data were available for 186 participants (95 treatments, 91 shams). There were no differences in pregnancy outcomes between groups (table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes: pregnancy outcomes

| Treatment (n=95) | Sham (n=91) | Treatment – sham Difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39.0 (38.0 to 39.9) | 39.0 (38.0 to 40.4) | −0.2* (−0.7 to 0.3) | 0.42 |

| OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Spontaneous vaginal | 55 (58%) | 43 (47%) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.9) | 0.19 |

| Caesarean section† | 40 (42%) | 46 (51%) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.3) | 0.30 |

| Vacuum extraction | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0 to 5.1) | 0.24 |

| Sex of newborn | ||||

| Male | 56 (59%) [2] | 43 (47%) [2] | 1.6 (0.9 to 3.0) | 0.14 |

| Stillbirth | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1.9 (0.1 to 113) | 1 |

| Low birth weight | 7 (8%) {12} | 6 (7%) {7} | 1.2 (0.3 to 4.5) | 0.78 |

| Small for gestational age | 12 (14%) {12} | 20 (24%) {7} | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.3) | 0.17 |

| Preterm delivery | 9 (9%) | 10 (11%) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.5) | 0.81 |

| Received ≥1 obstetrical diagnosis during labour/delivery | 39 (41%) | 46 (51%) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.3) | 0.24 |

Count data are presented as frequency (%) and Fisher’s exact test for count data was used to compute the OR.

Square brackets [number] indicate that data is missing for this number of participants.

Curly brackets {number} indicate that this number of participants were excluded from the analysis because their birth weight data were flawed (newborns were weighed on different newborn scales).

*Gestational age at delivery was non-normally distributed, is presented as median (IQR), and Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to test for difference.

†Note: the caesarean section rate at the study site for 2015, 2016 and 2017 was 47%, 47% and 46%, respectively.

Twenty-three participants (14 treatments, nine shams) in the BPS cohort had complete datasets for analysis and are presented in online supplementary file 4. There was no difference in adherence or sleep position between groups in the BPS cohort.

bmjopen-2018-022981supp004.pdf (52.2KB, pdf)

In the feedback interview, participants in the PrenaBelt group were more likely to state that with use of the PrenaBelt, over time, they learnt to not sleep on their backs and that they felt more alert during the day (see online supplementary file 5 for the complete analysis of participant feedback). Maternity personnel feedback indicates that introducing the PrenaBelt in an antenatal care setting by midwives in a timely fashion is feasible (see online supplementary file 6).

bmjopen-2018-022981supp005.pdf (108KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp006.pdf (19.2KB, pdf)

Adverse events

In assessing adverse events (AEs), all participants who entered the trial (n=200) were included. One-hundred-six AEs occurred. Ninety-five were classified as common AEs. Causality of all serious AEs (SAEs) and all AEs were assessed by the Principal Investigator and classified as related, probably, possibly or unrelated to the intervention/research. Of the 95 common AEs, nine (9.5%) were judged to be likely related to the intervention. This includes six (3% of n=200) who felt too hot and three (1.5% of n=200) who felt too itchy while wearing the device. Three stillbirths and six SAEs preceding or temporally associated with these stillbirths occurred, were assessed, and were judged unrelated to the research. There was no difference in the frequency of AEs or SAEs between groups by Fisher’s exact test.

Discussion

Principal findings

This was the first study to longitudinally assess the impact of an intervention for sleep position in pregnant women. Although birth weight and GROW centile were 110 g higher and 7% higher, respectively, in the PrenaBelt group than in the sham group, this was not statistically significant. Adherence was lower than anticipated. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated feasibility of introducing the PrenaBelt to pregnant women in an antenatal care setting by midwives and of use throughout the third trimester since participants were overall pleased with their experience using the PrenaBelt.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Throughout the third trimester (2.5 months), participants were adherent to the device a little over half (56%) of the time. This indicates that pregnant women may be less adherent to PT than non-pregnant individuals with obstructive sleep apnoea whose adherence to PT gradually decreases from 93% at 1 month,47 to 74% at 3 months48 and 60% at 6 months.49 The main factor reducing adherence to PT during late pregnancy in our trial was discomfort, and, specifically, that the PrenaBelt was too hot for the climate in Accra where average lows were ≥25°C during the trial period. Other factors inherent to pregnancy itself (eg, musculoskeletal pain, nocturia, sleep disruption) could have also reduced adherence.

For a discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the BPS datasets and analyses, see online supplementary file 4.

Meaning of the study

Low birth weight is a significant contributor to stillbirth and neonatal mortality and morbidity in Ghana and globally. Our results showed a 110 g and 7% increase in birth weight and GROW centile, respectively, with the PrenaBelt despite only 56% adherence, but this was not statistically significant. Perhaps low adherence hampered the ability of the PrenaBelt to increase birth weight and birth weight centile, and this may lend support from our subgroup analysis of participants with 50% or greater adherence where each 1% increase in adherence conferred a 0.5% increase in the GROW centile, but this was independent of the intervention. Strategies to maximise adherence to positional therapy in future studies are warranted.

The authors have previously called for the development and testing of a positional therapy device for pregnant women.4 11 The current study implemented such a device in a population of healthy, pregnant women during sleep in the home setting throughout the third trimester of pregnancy in Ghana. This study extends the work of previous studies demonstrating an association between maternal supine sleeping position in late pregnancy and the risk of late-term stillbirth4–8 and low birth weight4 by taking the next logical step in testing an intervention to minimise supine sleep throughout the third trimester. Birth weight was chosen as the primary outcome because it is a risk factor for stillbirth, and the latter outcome would demand a prospective cohort of thousands of women in order to be adequately powered, even in Ghana where perinatal mortality rates are higher than Western countries. Whereas efficacy research can maximise an intervention’s observed effect if one exists, the intervention’s effect in effectiveness research is often tempered by patient-, provider- and system-level50; therefore, this study also lends insight to our previous PrenaBelt studies in Australia and Canada9 10 by focusing on PrenaBelt performance under real-world conditions.

Our study demonstrates that left-sided sleeping position is common in late pregnancy, which is corroborated by other studies.7 9 10 Left-side preference is likely for comfort reasons as well as high prevalence of ‘sleep-on-side’ information from the internet, family and social networks and maternity care providers in Ghana.51 However, maternity care providers may need to recommend interventions to minimise unintentional supine sleep because, at baseline, most pregnant women continue to spend a significant amount of time sleeping supine in late pregnancy.9 11–13 Providers should be aware that pregnant women underestimate the time they spend sleeping supine.10 Further, a threshold for the proportion of supine sleep that is ‘acceptable’ is unknown. As with any intervention, providers should recognise that adherence will present challenges – its precise estimation is not easy and its underlying causes are often elusive. However, many of these challenges can be addressed and adherence optimised through a mutual provider-patient partnership that tailors the intervention to the unique characteristics of pregnant women.52

Strengths

This study was powered based on previous data from Ghana,4 and it was representative of the population of pregnant women receiving antenatal care at KBTH. The sham-PrenaBelt ensured that the participants in the sham group received every specific benefit of any element of the PrenaBelt above and beyond all benefits that might be attributed to its ability to cause pressure points and, thus, reduced treatment bias. Allocation concealment and randomisation of participants to the treatment or sham group helped avoid allocation bias. Blinding of participants and the outcome assessor further reduced potential sources of bias and strengthened data integrity as did double-entry of data and standardised birth weight measurement on digital newborn scales. This is the first study to investigate use of a positional therapy device by pregnant women in a longitudinal manner in the home setting – as such, the PrenaBelt was tested under real-world conditions. Inclusion of the GROW centile as a primary outcome enabled delineation between constitutional and pathological smallness.

Weaknesses

We did not incorporate infrared video confirmation of body position during sleep; however, use of video would not be practical or feasible in a longitudinal study, especially in a limited-resource setting.

Self-reporting of device use via the sleep diary introduced inaccuracy in estimating the adherence rate. A small number of participants indicated that they used their device more nights than they were in the trial; however, in our analysis, we accounted for and corrected this.

We did not include objective measures of sleep architecture, timing or duration via actigraphy or polysomnography; thus, we could not confirm sleep duration. However, in two previous studies of the PrenaBelt, the authors were unable to demonstrate an effect on sleep architecture or respiration using actigraphy9 and polysomnography.10

When instructed to sleep on their left, third-trimester pregnant women can increase the proportion of left-sided sleep and maintain this across multiple nights without a positional therapy device.13 Prior to randomisation, all participants learnt, during the consent process, that the reason for conducting the study was because supine sleep may be a risk factor for SB and LBW. Although participants were not instructed to avoid or prefer any given sleep position, they may have, by simple deduction, concluded that they should avoid supine sleep and prefer lateral sleep. However, since we did not ask participants about whether their sleep onset position changed after study entry, we were unaware of this happening, and this effect, if any, would have been equal across both groups.

Comparison of feedback between participants in the PrenaBelt and sham-PrenaBelt groups (see supplementary file 5) may be biased due to limited inclusion of the sham-PrenaBelt participants up until 2 March, 2016, when it was discovered that feedback from the sham-PrenaBelt participants was being inadvertently collected and this collection was subsequently stopped.

We acknowledge the possibility that a participant may have become un-blinded if she had a friend that was in the alternate treatment group and sought to compare devices. We also acknowledge that randomisation using unmarked, security-tinted, sealed envelopes can be subverted.53 However, we were unaware of anything like this happening or what effect it may have had.

The current study was conducted in a cohort of healthy, non-obese, Ghanaian pregnant women; as such, the results may not be generalisable to women with medical or pregnancy complications, differing ethnicity or living in other parts of the world. Household income of our participants was comparable to the national average, but the majority (85%) had a high-school or tertiary-level education, which is significantly more than the national average in Ghana and could limit the generalisability of our results.54

The current study may be underpowered because despite being based on a previous Ghanaian study by Owusu et al,4 the latter study was small. As women were adherent to the intervention for little over half the time, the current study may be underpowered to detect a clinically meaningful difference.

We did not collect smoking data, which is a relevant risk factor for low birth weight. However, among females in Ghana, the prevalence of current smoking is 0.3% (95% CI 0.1% to 0.4%) and the prevalence of ever smoking is 1.2% (95% CI 0.7% to 1.6%).55 Therefore, the impact of smoking on birth weight in the current study is, at most, negligible.

Future research

Given the impact that adherence has on outcomes, research that incorporates measures to accurately elucidate adherence rates and reasons for non-adherence is imperative. Feedback from participants in this trial can be used to improve the PrenaBelt design for increased adherence. Incorporation of accurate and objective measures of body position will eliminate the need to rely on participants’ self-reports and will enable quantification of supine time for linkage to outcomes. If sleeping supine is potentially harmful to the foetus, the amount of supine time that is harmful needs quantification in order to target interventions to avoid this. The results of this trial warrant future, large, multi-ethnic studies that include women with a range of pregnancy and medical conditions to ascertain if the observed effects persist.

Other information

Protocol

Full details of the trial protocol are available with the full text of this article (see online supplementary file 7).

bmjopen-2018-022981supp007.pdf (8.8MB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 200 pregnant volunteers who took part in this trial; Josephine Kwaw, Jemima Marfo, Rose Quartey and Joyce Doodo for their support as research assistants; Kevin Li for his expertise in writing the custom Java code to process the raw BPS data; Abdullah Saleh and David Janzen of ICChange (Edmonton, Canada) for administrative support; Dr Samuel Asiamah, Director of Medical Affairs, KBTH, and the late Professor Samuel Amenyi Obed, Head of Department, Obstetrics & Gynaecology Department, KBTH, for their support. There were no patient advisers. Dr Kember would like to especially thank the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation for support through the Lalia B. Chase Summer Research Studentship and Dalhousie Medical School for support through the Faculty of Medicine Summer Studentship.

Footnotes

Contributors: AK designed the protocol, secured funding, ethics approval and the research contracts, trained the study personnel, maintained the sponsor study master record, monitored data collection, cleaned and analysed the data and drafted and revised this manuscript. He is guarantor. AK and AB conceptualised the PrenaBelt. KC designed and manufactured the PrenaBelt research samples. JC, JS, HS, LMO’B, AB, MB, MO and AI designed the protocol. JC oversaw participant recruitment and follow-up, maintained the investigator study master record, hosted Ghana FDA trial site inspections and was the Principal Investigator responsible for all aspects of the trial. JC and AK liaised with the Ghana FDA to secure the clinical trial certificate and report trial activities and results. JS was the independent trial monitor and conducted quarterly monitoring reviews at the trial site. MB and MO wrote the statistical plan and oversaw the statistical analysis. MO was the blinded outcomes assessor. JW maintained the sponsor study master record, monitored data collection, double entered PDF data into Excel and cleaned and analysed the data. SM monitored data collection and double entered PDF data into Excel. AI negotiated the research contract and managed the trial funds. JC, JS, MO, MB, HS, LMO’B, AB, JW, SM, KC and AI made intellectual contributions to this manuscript.

Funding: This trial was supported by funding from Grand Challenges Canada Stars in Global Health Award, Round 7, Number 0629-01-10. Grand Challenges Canada is funded by the Government of Canada. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: Dr Kember and Dr Borazjani, are officers at GIRHL, which has a patent application for the PrenaBelt (#WO2016176632A1) on which Dr Kember, Dr Borazjani and Ms Chu are listed as Inventors. Dr Coleman, Mr Okere, Professor Seffah, Mr Wells, Ms MacRitchie, Dr Scott, Mr Butler, Dr Isaac and Dr O’Brien have declared no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data analysis scripts and output are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. WHO | Stillbirths [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization. 2018. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/stillbirth/en/ (cited 22 Sep 2018).

- 2. Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, et al. . National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. Elsevier 2011;377:1319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wardlaw T, Blanc A, Zupan J. Low Birthweight [Internet]. 2004. New York http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/low_birthweight_from_EY.pdf (cited 15 Jun 2016).

- 4. Owusu JT, Anderson FJ, Coleman J, et al. . Association of maternal sleep practices with pre-eclampsia, low birth weight, and stillbirth among Ghanaian women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;121:261–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stacey T, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, et al. . Association between maternal sleep practices and risk of late stillbirth: a case-control study. BMJ 2011;342:d3403 10.1136/bmj.d3403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gordon A, Raynes-Greenow C, Bond D, et al. . Sleep position, fetal growth restriction, and late-pregnancy stillbirth: the Sydney stillbirth study. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:347–55. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCowan LME, Thompson JMD, Cronin RS, et al. . Going to sleep in the supine position is a modifiable risk factor for late pregnancy stillbirth; Findings from the New Zealand multicentre stillbirth case-control study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179396 10.1371/journal.pone.0179396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heazell A, Li M, Budd J, et al. . Association between maternal sleep practices and late stillbirth - findings from a stillbirth case-control study. BJOG 2018;125:254–62. 10.1111/1471-0528.14967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warland J, Dorrian J, Kember AJ, et al. . Modifying Maternal Sleep Position in Late Pregnancy Through Positional Therapy: A Feasibility Study. J Clin Sleep Med 2018;14:1387–97. 10.5664/jcsm.7280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kember AJ, Scott HM, O’Brien LM, et al. . Modifying maternal sleep position in the third trimester of pregnancy with positional therapy: a randomised pilot trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020256 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Brien LM, Warland J. Typical sleep positions in pregnant women. Early Hum Dev 2014;90:315–7. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McIntyre JP, Ingham CM, Hutchinson BL, et al. . A description of sleep behaviour in healthy late pregnancy, and the accuracy of self-reports. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:115 10.1186/s12884-016-0905-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warland J, Dorrian J. Accuracy of self-reported sleep position in late pregnancy. PLoS One 2014;9:e115760 10.1371/journal.pone.0115760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Courtney L. Supine hypotension syndrome during caesarean section. Br Med J 1970;1:797–8. 10.1136/bmj.1.5699.797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holmes F. Spinal analgesia and caesarean section; maternal mortality. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1957;64:229–32. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1957.tb02626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holmes F. The supine hypotensive syndrome. 1960. Anaesthesia 1995;50:972–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb05931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holmes F. Incidence of the supine hypotensive syndrome in late pregnancy. A clinical study in 500 subjects. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1960;67:254–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1960.tb06987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kauppila A, Koskinen M, Puolakka J, et al. . Decreased intervillous and unchanged myometrial blood flow in supine recumbency. Obstet Gynecol 1980;55:203–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kinsella SM, Lee A, Spencer JA. Maternal and fetal effects of the supine and pelvic tilt positions in late pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1990;36(1-2):11–17. 10.1016/0028-2243(90)90044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kinsella SM, Lohmann G. Supine hypotensive syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 1994;83(5 Pt 1):774–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo CD, Chen GY, Yang MJ, et al. . The effect of position on autonomic nervous activity in late pregnancy. Anaesthesia 1997;52:1161–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.254-az0387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee SW, Khaw KS, Ngan Kee WD, et al. . Haemodynamic effects from aortocaval compression at different angles of lateral tilt in non-labouring term pregnant women. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:950–6. 10.1093/bja/aes349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lees MM, Scott DB, Kerr MG, et al. . The circulatory effects of recumbent postural change in late pregnancy. Clin Sci 1967;32:453–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lees MM, Taylor SH, Scott DB, et al. . A study of cardiac output at rest throughout pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1967;74:319–28. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1967.tb03956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Milsom I, Forssman L. Factors influencing aortocaval compression in late pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;148:764–71. 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90563-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rossi A, Cornette J, Johnson MR, et al. . Quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance in pregnant women: cross-sectional analysis of physiological parameters throughout pregnancy and the impact of the supine position. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2011;13:31 10.1186/1532-429X-13-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharwood-Smith G, Drummond GB. Hypotension in obstetric spinal anaesthesia: a lesson from pre-eclampsia. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:291–4. 10.1093/bja/aep003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Humphries A, Mirjalili SA, Tarr GP, et al. . The effect of supine positioning on maternal hemodynamics during late pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018;8:1–8. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1478958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khatib N, Haberman S, Belooseski R, et al. . 701: Maternal supine recumbency leads to brain auto-regulation in the fetus and elicit the brain sparing effect in low risk pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:S278 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.10.723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carbonne B, Benachi A, Lévèque ML, et al. . Maternal position during labor: effects on fetal oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:797–800. 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Humphries A, Stone P, Mirjalili SA. The collateral venous system in late pregnancy: A systematic review of the literature. Clin Anat 2017;30:1087–95. 10.1002/ca.22959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cartwright RD. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep 1984;7:110–4. 10.1093/sleep/7.2.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oksenberg A. Positional and non-positional obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med 2005;6:377–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ding XX, Wu YL, Xu SJ, et al. . A systematic review and quantitative assessment of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. Sleep Breath 2014;18:703–13. 10.1007/s11325-014-0946-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. . Snoring during pregnancy and delivery outcomes: a cohort study. Sleep 2013;36:1625–32. 10.5665/sleep.3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. . Pregnancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:487.e1–487.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oksenberg A, Gadoth N. Are we missing a simple treatment for most adult sleep apnea patients? The avoidance of the supine sleep position. J Sleep Res 2014;23:204–10. 10.1111/jsr.12097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ravesloot MJ, van Maanen JP, Dun L, et al. . The undervalued potential of positional therapy in position-dependent snoring and obstructive sleep apnea-a review of the literature. Sleep Breath 2013;17:39–49. 10.1007/s11325-012-0683-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berger M, Oksenberg A, Silverberg DS, et al. . Avoiding the supine position during sleep lowers 24 h blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients. J Hum Hypertens 1997;11:657–64. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Permut I, Diaz-Abad M, Chatila W, et al. . Comparison of positional therapy to CPAP in patients with positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:238–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eijsvogel MM, Ubbink R, Dekker J, et al. . Sleep position trainer versus tennis ball technique in positional obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:139–47. 10.5664/jcsm.4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gardosi J, Francis A. Customized Weight Centile Calculator [Internet]. Gestation Network 2016. www.gestation.net. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gardosi J, Chang A, Kalyan B, et al. . Customised antenatal growth charts. Lancet 1992;339:283–7. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91342-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gardosi J. New definition of small for gestational age based on fetal growth potential. Horm Res 2006;65 Suppl 3(SUPPL. 3):15–18. 10.1159/000091501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Odibo AO, Francis A, Cahill AG, et al. . Association between pregnancy complications and small-for-gestational-age birth weight defined by customized fetal growth standard versus a population-based standard. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:411–7. 10.3109/14767058.2010.506566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Core Team R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016. https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 47. van Maanen JP, Meester KA, Dun LN, et al. . The sleep position trainer: a new treatment for positional obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Breath 2013;17:771–9. 10.1007/s11325-012-0764-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Heinzer RC, Pellaton C, Rey V, et al. . Positional therapy for obstructive sleep apnea: an objective measurement of patients' usage and efficacy at home. Sleep Med 2012;13:425–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Maanen JP, de Vries N. Long-term effectiveness and compliance of positional therapy with the sleep position trainer in the treatment of positional obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 2014;37:1209–15. 10.5665/sleep.3840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Singal AG, Higgins PD, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2014;5:e45 10.1038/ctg.2013.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Okere M, Coleman J, Seffah JD, et al. . KBTH-GIRHL Healthy Birth Weight Study: A Cross-Section [Internet]. 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03062228 (cited 2018 Oct 6).

- 52. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, et al. . The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005;1:189–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vickers AJ. How to randomize. J Soc Integr Oncol 2006;4:194–8. 10.2310/7200.2006.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS-6) [Internet]. Accra 2014. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/glss6/GLSS6_Main Report.pdf (cited 2018 Oct 6). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Owusu-Dabo E, Lewis S, McNeill A, et al. . Smoking uptake and prevalence in Ghana. Tob Control 2009;18:365–70. 10.1136/tc.2009.030635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022981supp001.pdf (73.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp002.pdf (35.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp003.pdf (48.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp004.pdf (52.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp005.pdf (108KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp006.pdf (19.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022981supp007.pdf (8.8MB, pdf)