Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death globally. In outpatient care, the self-management of COPD is essential, but patient adherence to this remains suboptimal. The objective of this study is to examine whether an innovative mobile health (mHealth)-enabled care programme (MH-COPD) will improve the patient self-management and relevant health outcomes.

Methods and analysis

A prospective open randomised controlled trial has been designed. In the trial, patients with COPD will be recruited from The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia. They will then be randomised to participate in either the MH-COPD intervention group (n=50 patients), or usual care control group (UC-COPD) (n=50 patients) for 6 months. The MH-COPD programme has been designed to integrate an mHealth system within a clinical COPD care service. In the programme, participants will use a mHealth application at home to review educational videos, monitor COPD symptoms, use an electronic action plan, modify the risk factors of cigarette smoking and regular physical activity, and learn to use inhalers optimally. All participants will be assessed at baseline, 3 months and 6 months. The primary outcomes will be COPD symptoms and quality of life. The secondary outcomes will be patient adherence, physical activity, smoking cessation, use of COPD medicines, frequency of COPD exacerbations and hospital readmissions, and user experience of the mobile app.

Ethics and dissemination

The clinical trial has been approved by The Prince Charles Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/QPCH/252). The recruitment and follow-up of the trial will be from January 2019 to December 2020. The study outcomes will be disseminated according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement through a journal publication, approximately 6 months after finishing data collection.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618001091291.

Keywords: chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, randomized controlled trial, self-management, mobile health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Integration of an innovative mobile health (mHealth) system with a clinical chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) care service can potentially improve the self-management of COPD by patients.

The mHealth system being tested delivers core recommendations for the self-management of COPD as advocated by the evidence-based guidelines.

Specific health outcomes of relevance to the self-management will be measured in this mHealth study.

The study is limited to a 6-month intervention period, and as a purely self-management programme, the mobile phone application does not include remote, real-time monitoring of patient outcomes by clinicians.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive chronic lung disease, ranked as the fourth leading cause of death globally and affecting over 200 million people.1 Patients with COPD have persistent respiratory symptoms and chronic airflow limitation, and often experience episodic exacerbations of COPD. Consequently, they have high risks of hospital readmission, with reported 30-day readmission rates ranging from 10% to 20%.2 3

The self-management of COPD through clinical and social support, such as optimal use of medicines, lifestyle modification and avoidance of risk factors, is essential to improve health outcomes and prevent COPD progression.4 5 Accordingly, evidence-based self-management principles are recommended in clinical guidelines for COPD. Unfortunately, patient adherence with self-management is often suboptimal.6 For example, studies have demonstrated that only 40%–60% of patients with COPD adhere with their inhaled medicines to control COPD symptoms,7–9 and about 50% do not undertake physical activities regularly as recommended by the guidelines.10 Similarly, over 24% of patients with COPD remain current cigarette smokers in Australia,11 although smoking has been well known as the most important risk factor for COPD.12 Moreover, many patients often take a wait-and-see approach with self-management, and, hence, fail to seek timely interventions for exacerbations.13 Barriers to the patient adherence are complex and multifaceted, likely including limited health knowledge, difficulty to access resources, insufficient clinical support and lack of motivation.13 14

Recently, mobile health (mHealth)—defined as the use of mobile and wireless technologies for healthcare15—has become a new treatment approach which can empower self-management and enhance proactive clinical interventions.16 For COPD, a number of mHealth applications are now available in the market.17 Feasibility studies have demonstrated a high level of acceptance by patients18 and many potential benefits such as knowledge gained, improved physical activities, reduced dyspnoea19 and ability to remotely assess COPD exacerbations.20 21 A recent systematic review, evaluating outcomes from six randomised controlled trials (RCTs), demonstrated the potential to use smartphone applications to reduce COPD exacerbation rates, but at the same time indicated the limitations of studies to date, including inadequate sample sizes (≤100) and heterogeneity in study design.22 Therefore, additional high-quality evidence remains essential to enable practical implementation of mHealth for the management of COPD in clinical settings.

In this study, we propose an innovative mHealth programme for COPD (MH-COPD). The programme has been specifically designed to integrate an mHealth system within an existing COPD care service to deliver all core components advocated by the evidence-based clinical guidelines in Australia. The MH-COPD programme will make it easy for patients to access validated educational materials, and self-manage clinical symptoms. The integration with the clinical service will also enable care providers to support and motivate patients to adhere to the self-management of COPD. We hypothesise that the MH-COPD programme would enhance the self-management of COPD by patients that is consistent with guideline principles, and consequently improve health outcomes. We have therefore designed an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of the MH-COPD programme.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

The research questions on improving the self-management of COPD, and outcome measures were developed according to the clinical practice in Queensland, and suggestions from Lung Foundation Australia, a not-for-profit organisation representing consumers with respiratory conditions. In design of the mHealth system, we employed an existing framework developed by The Australian e-Health Research Centre (Brisbane, Australia). This framework has been successfully used in a number of studies to assist patients in managing health conditions23 24 and chronic diseases, including COPD,20 21 diabetes25 and cardiovascular disease.26 27 In this project, we also engaged with clinical nurses, general practitioners, thoracic physicians and a group of patients with COPD. With this engagement, we identified the care needs for the self-management of COPD. We accordingly designed the interventional components and care processes. Finally, we worked with the clinician and patient groups to design the user interface for the mobile app and clinician portal.

Patients with stable COPD will be recruited to examine the efficacy of the MH-COPD programme. The study outcomes will be disseminated through a journal publication, approximately 6 months after finishing data collection. For the participants to be informed of the outcomes, we will send the final publication to them by email.

Trial design and clinical setting

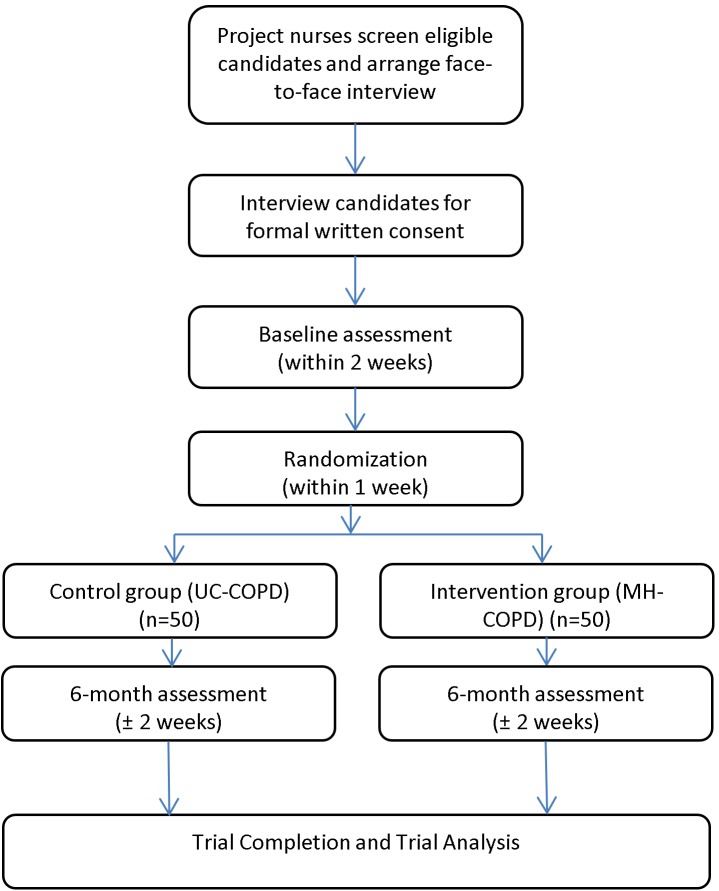

The clinical trial will be a prospective, open, parallel group, two-arm RCT. We will recruit 100 patients with COPD from The Prince Charles Hospital (TPCH), Brisbane, Australia. The recruitment and follow-up of the trial will be from January 2019 to December 2020. The study flow chart is shown in figure 1. Written informed consent will be obtained. Using allocation concealment, participants will be randomised to receive either the MH-COPD programme (n=50 patients) or usual care (UC-COPD) (n=50 patients) for a study duration of 6 months. All participants will be assessed at baseline, 3 months and 6 months.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart of the randomised controlled trial designed to evaluate the mobile health programme for the self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (MH-COPD). UC, usual care.

Patients with COPD attending the thoracic outpatient clinics at the hospital will be screened for eligibility. Each potential candidate will be provided with a participant information sheet about the research study and a consent form. If a candidate is willing to participate in the trial, written informed consent will be obtained. Each participant will be interviewed face to face by the clinical research staff (nurses or physicians) in the trial as a baseline assessment.

Eligibility criteria

Adult patients with COPD will be invited to participate in this trial. The inclusion criteria will be: (1) diagnosis of COPD, defined according to the international Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines,28 (2) chronic airflow limitation that is not fully reversible (postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC<70% and FEV1 <80% predicted) and (3) current or former smokers, with a smoking history of >10-pack years.

The exclusion criteria will be: (1) women who are pregnant, (2) with age less than 18 years, (3) with an intellectual or mental impairment, (4) other comorbid lung diseases that would potentially interfere with study outcomes (predominant asthma based on physician diagnosis, active lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, severe bronchiectasis) and (5) limitations to the use of mobile technology (non-correctable vision, hearing, cognitive or dexterity impairment).

Randomisation

A series of random assignment forms with permuted blocks will be generated according to a published method.29 The block size will be confidential. The randomisation will be stratified by participant’s sex (male and female) to ensure a balanced allocation. Assignment forms will be printed and sealed in opaque envelopes according to a predefined order. The envelopes will be stored in a secured cabinet. Following the order, the clinical research staff will open the next available envelope for each eligible participant, to reveal the assignment for the participant.

Baseline assessment

Clinical characterisation will be undertaken at baseline:

Demographics and respiratory history will be obtained, including smoking history, respiratory symptoms, chronic bronchitis, respiratory medications, oxygen use, frequency of exacerbations of COPD requiring antibiotics and/or steroids in the past 12 months.

COPD symptoms and quality of life: the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale will be administered.

Lung function: the most recent results for prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator spirometry, and gas transfer as physiological indicator of emphysema, will be recorded. These assessments will be performed, if they are unavailable within the previous 12 months.

COPD knowledge will be assessed with a questionnaire,30 based on the content of Lung Foundation Australia resources.

Questionnaire on mobile technology: participants will be surveyed on their attitudes and beliefs about using mobile technologies (eg, smartphones), and will be asked about their current use of mobile phone.

MH-COPD intervention group

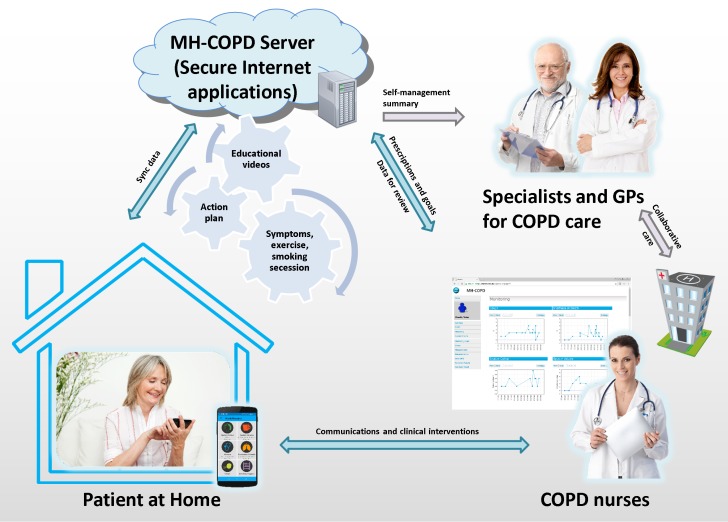

The MH-COPD programme will implement an mHealth system as an intervention, in addition to usual care. The mHealth system will comprise an Android smartphone application (app) and a secure online clinician portal. Participants will be informed that the MH-COPD programme is not a replacement for their usual clinical care, but is an add-on, and they should contact their general practitioner, respiratory nurse or respiratory specialist as usual if they have any concerns about their COPD. The care model of the MH-COPD programme is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

The care model of the mobile health programme for the self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (MH-COPD) includes the components of health education, electronic COPD action plan, symptom monitoring, physical activity, smoking cessation and inhaler technique. GP, general practitioner.

Resources provided

In the intervention group, an Android smartphone with a prepaid SIM card will be provided to each participant, with the COPD app fully installed. If a participant wishes to use his/her personal smartphone, the research staff will ensure the participant’s phone is compatible with the app and then will install the app. Participants using their own personal smartphone will be provided a mobile data voucher to cover the cost of Internet data transmission. A paper-based instruction manual of the MH-COPD programme will be provided to help the participant to use the app and receive interventions.

Study procedures and interventions

Each participant will be provided with an education and training session, of up to 1-hour duration, to provide instructions and demonstrate how to use the app. During the session, the research staff will introduce the MH-COPD programme, and will then register the participant through the online clinician portal. After the registration, an SMS message, containing the log-in formation and a website for downloading the app, will be automatically sent to the participant’s mobile phone. The research staff will then guide the participant to receive the message, download the app and log into the app. After the registration, the research staff will help the participant create self-management tools, according to the COPD app functions described below:

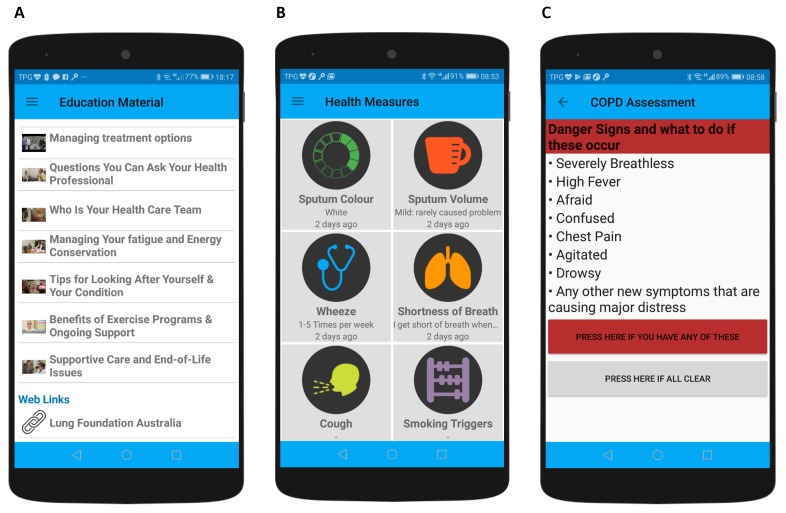

Health education: 10 video clips will be automatically provided to the participants via the app at scheduled times (figure 3A), at a rate of two videos per week for the first 5 weeks. The video clips have been prepared and validated by Lung Foundation Australia.31 Through the video clips, participants will gain essential knowledge on 10 topics: (1) managing your lung disease, (2) How do your lungs work? (3) managing your breathlessness, (4) managing treatment options, (5) questions you can ask your health professional, (6) Who is your healthcare team? (7) managing your fatigue and energy conservation, (8) tips for looking after yourself and your condition, (9) benefits of exercise programmes and ongoing support and (10) supportive care and end-of-life issues. The duration of each video clip ranges from 6 to 12 min. The video clips are integrated in the app, and after each video, a questionnaire will be given to help participants self-assess the knowledge obtained. Links to the webpages of Lung Foundation Australia, Asthma Australia and the Australian Government Quitline for smoking cessation will be included in the app, to enable direct access from the smartphone to these sites.

Symptom monitoring: participants will use the app each day to self-manage COPD symptoms, including breathlessness, cough, sputum colour, sputum volume and wheezing (figure 3B). The severity levels of the symptoms will be predefined, and scored on the app. The recorded symptoms of individual participants will be automatically compared with those in the previous day. If two or more symptoms of a participant are detected with increased scores, the participant will be notified via an automated smartphone notification to use an electronic COPD action plan in the app.

Electronic COPD action plan: participants will work through an electronic COPD action plan in the app on a daily basis. The action plan will contain three sections based on symptom severity: danger signs (figure 3C), signs of a flare-up and staying well. It will contain recommendations for medicines prescribed for worsening symptoms and exacerbations. The medicines will include bronchodilators, antibiotics and oral steroids, and will be entered into the action plan in the app by the research staff during the education and training session. The sections and corresponding recommendations in the app will replicate a paper-based COPD action plan clinically validated and used in Queensland Health. This will make it easy for patients to access and use the action plan. Participants in the intervention programme will still be required to engage with care providers to diagnose and treat clinical conditions, including acute exacerbations of COPD, as what they do in usual care.

Physical activity: the app will use inbuilt motion sensors in the smartphone to automatically record walking steps. Participants will be asked to carry the smartphone with the app during normal activity in waking hours in order to capture walking activity. An initial personal goal for steps to walk will be prescribed32 for each participant, and this goal will be automatically increased in the first 4 weeks. Motivational messages will also be automatically sent to the participant according to the number of steps and goal achievement each day.

Smoking cessation: for current smokers, the participants will use the app to record the number of cigarettes consumed each day, triggers and cues for smoking cigarettes, attempts to reduce cigarettes and use of pharmacotherapy (such as nicotine replacement or varenicline). A goal of the maximum number of cigarettes consumed each day will be provided to each participant. The goal of cigarettes smoked will be automatically reduced down to zero through the first 6 week time period. Clinicians in the programme will discuss with individual participants to set the goal, and adjust the goal during follow-up. Motivational messages will be automatically generated and sent according to the number of cigarettes recorded daily and the goal achievement through the 6-week period.

Inhaler technique: the participants will use the app to review videos to learn to how to use inhalers correctly. The videos have been prepared and validated by Lung Foundation Australia33 and will be preloaded in the app, according to inhalers prescribed to individual participants. Videos of each participant actually using their inhalers will also be recorded by the research staff during the education and training session, and stored in the app for the participant to review.

Figure 3.

Selected screenshots showing the user interface of the mobile application. (A) Scheduled educational videos preloaded in the app. (B) User interface to record symptoms and risk factors. (C) User interface showing an assessment of symptoms in the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) action plan.

Monitoring of patient adherence

All the data entries of the participants recorded via the app, such as symptoms, the action plan and cigarettes, will be automatically uploaded to the online portal and analysed to assess the patient adherence. If a participant does not adhere to programme for 2 days, alerts will be generated in the portal, and automated motivational messages will be sent to the participant via app notifications. The research staff will review the alerts in the portal and accordingly contact the participant to troubleshoot the nonadherence.

Diary card for exacerbations

Participants will keep a hard copy diary to record exacerbations and hospital admissions during the study. A COPD exacerbation will be defined as an increase in respiratory symptoms requiring treatment with systemic steroids and/or antibiotics.34 Participants will record the start and end date of treatment for the exacerbation. The research staff based at TPCH will phone each participant at 2 weeks, 2 months and 4 months, to ensure adherence to the exacerbation diary and reporting of exacerbations, as well as adherence to the app. The data in the diary will be collected and analysed to assess the frequency, duration and severity of exacerbations in the participants.

Usual care group

Usual care

Participants in the usual care (UC-COPD) group will receive standard care from respiratory clinics and primary care, throughout the trial period.

Resources provided

No COPD app will be provided to the usual care group. A standard care package will be provided to help participants with usual care, including general written advice about health education, the COPD action plan, symptom monitoring, physical activity, smoking cessation and inhaler technique. In the package, the information on the self-management of COPD from the Lung Foundation Australia and the corresponding web address will be provided.

Study procedures

After randomisation and baseline assessment, the research staff will train the participant on study procedures and take them through the instruction manual. These training and procedures will be the same as those provided in usual care in Queensland Health.

Diary card for exacerbations

Participants will keep a written, hard copy diary to record exacerbations and hospital admissions during the study, similar to the methods described in the intervention group.

Outcomes

The outcome measures of the study are shown in table 1. The primary outcome measures will be COPD symptoms and quality of life, assessed by the CAT,35 SGRQ36 and mMRC37 questionnaires at the baseline and 6-month time point. The CAT and SGRQ questionnaires will be used because they are responsive to interventions.38 We will also include mMRC because it is essential for assessing dyspnoea, and has been adopted in GOLD28 and Australian COPD-X guidelines.4 The secondary outcomes will include the inhaled medicine adherence (Test of the Adherence to Inhalers [TAI]),39 smoking cessation and physical activity by Global Physical Activity Questionnaire.40 Smoking cessation will be defined as zero cigarettes smoked in the last 7 days of the 6-month follow-up period after commencement of the intervention, as assessed through the self-reported diary. To assess the risk of COPD exacerbation, we will analyse the rate of COPD exacerbations recorded in the diary and MH-COPD system. Additionally, we will assess the healthcare utilisations relevant to hospital readmissions and visits of the emergency department. These events will be obtained from the hospital information systems in the trial.

Table 1.

Study outcome measures and assessment tools and data resources

| Baseline | 6 months | Methods/instruments | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| COPD symptoms and quality of life | Y | Y | CAT, SGRQ and mMRC |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| COPD knowledge | Y | Y | Lung Foundation Australia questionnaire on COPD knowledge |

| Inhaled medicine adherence | Y | Y | TAI questionnaire |

| Use of COPD action plan | N | Y | Self-reported in diary |

| Smoking cessation | Y | Y | Self-reported in diary |

| Physical activity | Y | Y | GPAQ (both groups), step count (intervention group) |

| Exacerbation rate | N | Y | Exacerbations recorded on hard copy exacerbation diary (both groups) and on the app (intervention group) |

| Healthcare utilisation | N | Y | Hospital readmissions and visits to the emergency department via hospital information systems |

| User experience of the mobile app | N | Y | Questionnaire (intervention group) |

CAT, COPD Assessment Test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GPAQ, Global Physical Activity Questionnaire; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TAI, Test of the Adherence to Inhalers.

Sample size

For the participants in the MH-COPD group, we will report the adherence quantified by the daily data entries recommended, and user experience assessed by a questionnaire previously applied in a previous mHealth-based study.25

The sample size has been calculated based on the coprimary outcomes of the CAT score and SGRQ score. One hundred patients, randomised 1:1 to intervention (MH-COPD) or usual care (UC-COPD), will have 80% power at significance level (alpha) of 0.05 to detect a clinically important reduction of 3 in the CAT score38 (primary outcome) in ~50% of intervention patients, compared with 20% in the control group, even with 40 patients in each final group (allowing for up to 20% withdrawal). In addition, this sample size will have 80% power at significance level (alpha) of 0.05 to detect a relative risk of 2 for a clinically important increase in SGRQ of 4 (coprimary outcome) in the intervention group, given a proportion of 30% of the control group achieving this with usual care, even with 40 patients in each final group (allowing for up to 20% withdrawal).

Blinding

This is an open RCT, due to the difficulty in effectively blinding participants and clinical researchers to the treatment groups. Data analysis of outcomes based on questionnaires and diary cards (common to both groups) will be analysed by a researcher not directly involved with recruitment and follow-up. In the analysis, only deidentified data will be provided.

Data collection and storage

The research staff will interview each participant at baseline to collect the data patient characteristics and conduct the assessments for those questionnaire-based outcomes. During the interview, the participant will receive paper-based assessment forms (questionnaires), and will be given sufficient time for the completion of these. The completeness of each questionnaire will be checked at the end of the interview by the research staff for quality purposes.

All study files, including the questionnaire forms, master list of participants and case report forms, will be stored securely, either in password-protected computer files (for electronic files) or in locked filing cabinets (for hard copies) in a secure area. Access to these files will only be granted to the study personnel trained in confidentiality and privacy procedures. All trial data provided for research analysis will be deidentified, including patient characteristics, primary and secondary outcomes, and data entries through the online portal systems used in the study.

All the trial files and data will be stored securely for a minimum of 5 years after the completion of the study and, finally, be securely destroyed according to the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council code for responsible conduct of research guidelines.41

Strategies for participant retention

Prior to the trial recruitment, the research team will discuss the importance of participant retention within the recruitment and care teams. During the trial, each participant will be provided with a telephone contact in the information package. Accordingly, the participants can contact the research staff for trial-related support. A structured procedure and log files will be in place to guide the research staff to document the participants’ enquiries, and ensure timely responses and/or follow-ups. Additionally, we will reimburse the participants for trial-related expenses including Android smartphone handsets if needed, mobile Internet costs and parking fees for interviews and assessments.

Statistical methods

All participants randomised into this study will be included in the final comparative analysis on an intention-to-treat basis. A χ2 test will be used to compare categorical variables between the MH-COPD and UC-COPD group. Analysis of variance will be applied to compare continuous variables between the groups. We will also analyse fluctuations of monitored symptoms to predict COPD exacerbations for early intervention. In this predictive analysis, we will use a nonlinear regression method, such as the exponential regression model previously applied,20 to analyse the relationship between the changes in symptoms and occurrence of exacerbations. In these comparison and analysis methods, a p-value less than 0.05 (two tailed) will be considered statistically significant. The analysis will be adjusted for confounding variables including age and sex. We will mainly use SPSS V.23 for the statistical analysis. Missing data at the case level will be imputed using a multiple imputation method implemented in SPSS.

Trial management

A trial steering committee will convene monthly (with additional meetings if needed) and take overall responsibility for the conduct of the trial. The committee will comprise representatives of the chief investigators, research staff and project managers from the collaborating organisations. The responsibilities of the committee include managing the trial progress, reviewing adverse events, resolving technical issues, monitoring trial data, providing reports to the project sponsors and ethics committees, and deciding budget and administration issues. If necessary, the committee will advise and make changes to the clinical trial protocol. The committee will be independent from project sponsors and free from competing interests.

Trial monitoring

A data monitoring committee (DMC), comprising four clinical researchers not directly involved in the study, will evaluate safety throughout the trial. The DMC will be independent from the trial sponsors and competing interests. The DMC will convene every 3 months (with additional meetings if needed) to review the risks and severity of adverse events or incidents reported. The statistical analysis methods and outcomes will be reviewed by a statistician. The DMC will assess the severity of adverse events and/or incidents, and provide recommendations if needed. If there are substantial differences in rates of serious adverse events (including mortality) or hospitalisation between the MH-COPD and UC-COPD groups, the DMC will investigate the potential reasons for the differences. If significant adverse events are caused by the MH-COPD programme, the DMC will recommend to terminate the trial early.

Limitations

A number of potential limitations should be considered. This study is limited to a 6-month intervention duration, which may be insufficient to reflect long-term effects of the intervention. The study is also not blinded to participants and clinicians, although analysis of 6-month outcomes will be blinded. This is a hospital-based study, which limits generalisability; however, future studies will address initiating of mHealth for patients with COPD in primary care.

Discussion

Currently, many mobile apps for COPD are available in the market, but they often have limited features or focuses.17 Importantly, the clinical evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness is generally absent.17 22 42 Recently, several RCT studies evaluated potential benefits to use mHealth for COPD, but they are normally limited by small sample sizes (n≤100) and narrow scopes, such as intervention of worsening COPD symptoms,43–45 physical activities19 46 47 or impacts of environment/climate change.48 Moreover, many mHealth studies for COPD have been found with many issues, such as high drop-out rates (20%,45 33%47 and 36%,19 large variations of patient adherence (20%47 to 98%44 adherence rates), and inconsistent user experience (mixed with technical challenges19 and good satisfactions47). Therefore, further clinical validation remains essential to use the mHealth for improving COPD care.

The MH-COPD programme has been deliberately designed to overcome those barriers stated before, and to focus on improving patient adherence to the self-management, consistent with the evidence-based clinical guidelines.4 In the programme, patients will use a mobile app to conveniently access educational videos to gain essential knowledge and skills as recommended by the guidelines. The app will also assist the patients in monitoring COPD symptoms and risk factors (low physical activity and smoking of cigarettes). Patients will interact with the electronic COPD action plan to make decision for significant changes in the symptoms, and receive automated motivational messages for the modification of the risk factors. The patients’ data, including monitoring symptoms, risk factors and adherence, will be automatically uploaded to the portal. Using the portal, the care providers are able to remotely monitor the patient conditions and adherence, and accordingly provide timely interventions. Compared with the paper-based approach in usual care, the use of mHealth would make it easier and simpler for the patients to access clinical resources and self-manage COPD. Additionally, it would allow the care providers to actively engage with the patients in COPD care. Therefore, we expect the MH-COPD programme to improve the patient compliance and health outcomes.

Different from many existing studies, our MH-COPD programme was designed to include all core components outlined by the evidence-based guidelines in Australia, and integrate within COPD clinics. Additionally, the programme aims at improving patient self-management. Although the nurses and COPD physicians in the programme will review the patients’ data through the clinician portal, their interventions mainly focus on supporting and motivating patients to adhere to the programme. Additionally, many automated messages and alerts will provided through the mHealth system to support the intervention. Therefore, the burden to the clinicians in the programme would be minimum. In all, the MH-COPD study will provide a unique opportunity to help understand the potential to use mHealth innovations to improve patient self-management and health outcomes, and hence add evidence for the effectiveness of using mHealth to improve COPD care in the community.

Summary

The study will specifically integrate an innovative mHealth system with a clinical COPD service and evaluate this approach through a RCT. The evaluation will provide a unique opportunity to improve COPD care in the community through mHealth innovations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients and staff of The Prince Charles Hospital for their involvement in this study, and contributors to the video clips prepared by Lung Foundation Australia.

Footnotes

Contributors: The MH-COPD program was designed by IAY, HD, DI, LM, RH, KP and PM. This study protocol was developed by IAY and HD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IAY and HD. All authors contributed to the design of the clinical study and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This project is funded by The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation, Brisbane, Australia (Experienced Researcher grant no. ER2015-21).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:404–6. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-405PS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harries TH, Thornton H, Crichton S, et al. Hospital readmissions for COPD: a retrospective longitudinal study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27:31 10.1038/s41533-017-0028-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shah T, Churpek MM, Coca Perraillon M, et al. Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansion. Chest 2015;147:1219–26. 10.1378/chest.14-2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang IA, Brown JL, George J, et al. COPD-X Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2017 update. Med J Aust 2017;207:436–42. 10.5694/mja17.00686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. COPD management. http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/management/en/ (Accessed 11 Nov 2017).

- 6. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, et al. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005;1:189–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cecere LM, Slatore CG, Uman JE, et al. Adherence to long-acting inhaled therapies among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD 2012;9:251–8. 10.3109/15412555.2011.650241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Restrepo RD, Alvarez MT, Wittnebel LD, et al. Medication adherence issues in patients treated for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008;3:371–84. 10.2147/COPD.S3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Low use and adherence to maintenance medication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:51–9. 10.1007/s11606-014-3029-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis AH. Exercise adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an exploration of motivation and goals. Rehabil Nurs 2007;32:104–10. 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Welfare AIoH. COPD, associated comorbidities and risk factors. 2016. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/asthma-other-chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd-associated-comorbidities-and-risk-factors/contents/risk-factors-associated-with-copd (Accessed 27 Nov 2017).

- 12. Tashkin DP, Murray RP. Smoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2009;103:963–74. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horie J, Murata S, Hayashi S, et al. Factors that delay COPD detection in the general elderly population. Respir Care 2011;56:1143–50. 10.4187/respcare.01109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanduzzi A, Balbo P, Candoli P, et al. COPD: adherence to therapy. Multidiscip Respir Med 2014;9:60 10.1186/2049-6958-9-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, et al. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ 2016;352:i1174 10.1136/bmj.i1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organisation. mHealth New horizons for health through mobile technologies. 2011. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf (Accessed 1 Jul 2017).

- 17. Sobnath DD, Philip N, Kayyali R, et al. Features of a Mobile Support App for Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Literature Review and Current Applications. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e17 10.2196/mhealth.4951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joe J, Demiris G. Older adults and mobile phones for health: a review. J Biomed Inform 2013;46:947–54. 10.1016/j.jbi.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nguyen HQ, Donesky-Cuenco D, Wolpin S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an internet-based versus face-to-face dyspnea self-management program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e9 10.2196/jmir.990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ding H, Karunanithi M, Kanagasingam Y, et al. A pilot study of a mobile-phone-based home monitoring system to assist in remote interventions in cases of acute exacerbation of COPD. J Telemed Telecare 2014;20:128–34. 10.1177/1357633X14527715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ding H, Moodley Y, Kanagasingam Y. A mobile-health system to manage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at home. Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference 2012. 2012:2178–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Alwashmi M, Hawboldt J, Davis E, et al. The effect of smartphone interventions on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e105 10.2196/mhealth.5921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duncan M, Vandelanotte C, Kolt GS, et al. Effectiveness of a web- and mobile phone-based intervention to promote physical activity and healthy eating in middle-aged males: randomized controlled trial of the ManUp study. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e136 10.2196/jmir.3107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ding H, Karunanithi M, Duncan M, et al. A mobile phone enabled health promotion program for middle-aged males. Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual Conference 2013. 2013:1173–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Ding H, Fatehi F, Russell AW, et al. User Experience of an Innovative Mobile Health Program to Assist in Insulin Dose Adjustment: Outcomes of a Proof-Of-Concept Trial. Telemed J E Health 2018;24:536–43. 10.1089/tmj.2017.0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walters DL, Sarela A, Fairfull A, et al. A mobile phone-based care model for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: the care assessment platform (CAP). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2010;10:5 10.1186/1471-2261-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varnfield M, Karunanithi M, Lee CK, et al. Smartphone-based home care model improved use of cardiac rehabilitation in postmyocardial infarction patients: results from a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2014;100:1770–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease I. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease pocket guide to copd diagnosis, management, and prevention: a guide for Health Care Professionals. 2017 edn, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care 2005;20:187–91. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lung Foundation Australia. C.O.P.E. Pre-Program Knowledge Questionnaire 2018. http://cope.lungfoundation.com.au/course/viewCourse/cid,26.html (Accessed 9 Feb 2018).

- 31. Lung Foundation Australia. Living with a lung condition. https://lungfoundation.com.au/patient-support/living-with-a-lung-condition/self-management/ (Accessed 11 Nov 2017).

- 32. Nolan CM, Maddocks M, Canavan JL, et al. Pedometer Step Count Targets during Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:1344–52. 10.1164/rccm.201607-1372OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lung Foundation Australia. Inhaler device technique. https://lungfoundation.com.au/patient-support/copd/inhaler-technique-fact-sheets/ (Accessed 11 Nov 2017).

- 34. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Inc. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2018 report). 2018.

- 35. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–7. 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, et al. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581–6. 10.1136/thx.54.7.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smid DE, Franssen FM, Houben-Wilke S, et al. Responsiveness and MCID Estimates for CAT, CCQ, and HADS in Patients With COPD Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Prospective Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:53–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Plaza V, Fernández-Rodríguez C, Melero C, et al. Validation of the ’Test of the Adherence to Inhalers' (TAI) for Asthma and COPD Patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2016;29:142–52. 10.1089/jamp.2015.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ v2.0). 2002. http://www.who.int/chp/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf (Accessed 9 Feb 2018).

- 41. National Health and Medical Research Council. Statement and Guidelines on Research Practice. 1997. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/r24 (Accessed 11 Nov 2017).

- 42. Velardo C, Shah SA, Gibson O, et al. Digital health system for personalised COPD long-term management. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017;17:19 10.1186/s12911-017-0414-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halpin DM, Laing-Morton T, Spedding S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effect of automated interactive calling combined with a health risk forecast on frequency and severity of exacerbations of COPD assessed clinically and using EXACT PRO. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:324–31. 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Farmer A, Williams V, Velardo C, et al. Self-management support using a digital health system compared with usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e144 10.2196/jmir.7116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pedone C, Chiurco D, Scarlata S, et al. Efficacy of multiparametric telemonitoring on respiratory outcomes in elderly people with COPD: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:82 10.1186/1472-6963-13-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu WT, Wang CH, Lin HC, et al. Efficacy of a cell phone-based exercise programme for COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:651–9. 10.1183/09031936.00104407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tabak M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, et al. A telehealth program for self-management of COPD exacerbations and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:935–44. 10.2147/COPD.S60179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jehn M, Donaldson G, Kiran B, et al. Tele-monitoring reduces exacerbation of COPD in the context of climate change--a randomized controlled trial. Environ Health 2013;12:99 10.1186/1476-069X-12-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.