Abstract

Objectives

Our aim was to assess the release level of heparin-binding protein (HBP) in sepsis and septic shock under the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3).

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

A general teaching hospital in China.

Participants

Adult infected patients with suspected sepsis and people who underwent physical examination were included. According to the health status and severity of illness, the research subjects were divided into healthy, local infection, sepsis non-shock and septic shock under Sepsis-3 definitions.

Main outcome measures

Plasma levels of HBP, procalcitonin (PCT), C reactive protein (CRP) and complete blood count were detected in all subjects. Single-factor analysis of variance was used to compare the biomarker levels of multiple groups. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the diagnostic capacity of each marker.

Results

HBP levels were significantly higher in patients with sepsis non-shock than in those with local infections (median 49.7ng/mL vs 11.8 ng/mL, p<0.01) at enrolment. Moreover, HBP levels in patients with septic shock were significantly higher than in patients with sepsis without shock (median 153.8ng/mL vs 49.7 ng/mL, p<0.01). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) of HBP (cut-off ≥28.1 ng/mL) was 0.893 for sepsis which was higher than those of PCT (0.856) for a cut-off ≥2.05 ng/mL and of CRP (0.699) for a cut-off ≥151.9 mg/L. Moreover, AUC of HBP (cut-off ≥103.5 ng/mL) was 0.760 for septic shock which was higher than the ROC curve of sequential [sepsis-related] organ failure assessment (SOFA) Score (0.656) for a cut-off ≥5.5. However, there was no significant difference between 28-d survivors (n=56) and 28-d non-survivors (n=37) with sepsis in terms of HBP value (p=0.182).

Conclusions

A high level of HBP in plasma is associated with sepsis, which might be a useful diagnostic marker in patients with suspected sepsis.

Keywords: heparin-binding protein, sepsis, septic shock, biomarkers

Strengths and Limitations of this study.

The research compared the concentrations of various biomarkers in groups with different disease statuses.

Sepsis 3.0 criteria were used in the study.

The single-centre source of patient samples was tested by the same laboratory using the same batch of reagents.

Some group was small in size and composition.

This is a non-consecutive study, in which data were obtained at one point in time with no serial measurements.

Introduction

The incidence of sepsis increases with ageing, rise in cancer incidence and popularity of invasive medical operations.1 2 Rapid detection and optimised treatment are the keys to successful treatment of sepsis.3 To facilitate earlier recognition and more timely management of patients with sepsis or those at risk of developing the condition, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and Society of Critical Care Medicine published new diagnostic criteria for sepsis and septic shock.4 Nevertheless, due to time delay, low sensitivity and lack of specificity,5 the existing diagnosis indicators such as microbial culture, complete blood count, and levels of procalcitonin (PCT) and C reactive protein (CRP) are inadequate for timely clinical diagnosis of sepsis and septic shock.

Heparin-binding protein (HBP) is precomposed and mainly exists in the azurophilic granules (almost 74% in content) and secretory vesicles (almost 18% in content) of neutrophils. Azurophilic granules show low tendency to be released from cells, and they are only released when neutrophils infiltrate tissues.6 The release of easily mobilised HBP from secretory vesicles has important functions during early events in inflammatory processes. HBP works by activating various cell types.7 Previous studies have shown that the plasma HBP level is significantly elevated in sepsis combined with organ dysfunction, which is the best probe for the progression of sepsis.3 8 Given the capacity of HBP to identify infection and vascular leakage in patients, it is also an interesting candidate marker to monitor patients with sepsis and septic shock. In this study, four groups (healthy, local infection, sepsis non-shock, septic shock) under the new diagnostic criteria were included. We analysed HBP and other biomarker levels in different groups to assess their diagnostic value in infected patients with sepsis and non-sepsis, as well as in patients with sepsis with septic shock and sepsis non-shock.

Materials and methods

Patient population

The case collection was performed at Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital (Zhejiang, China) between August 2017 and November 2017. The purpose of the research was explained in detail to all patients or their close relatives, and informed consent was obtained from themselves or next of kin (if the patient was in an unconscious state). The inclusion criteria were confirmed sepsis or clinically strongly suspected sepsis by the attending clinician. The exclusion criteria were as follows: age <18 years, pregnant, severe immunodeficiency and heparin therapy performed within 3 days of the study enrolment.

Data collection

Patients underwent an initial clinical assessment at enrolment, including demographics, comorbid conditions, medication usage, vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation) and mental status. Laboratory testing (HBP, PCT, CRP, white blood cells [WBCs], platelets, international normalised ratio, bilirubin, serum creatinine and arterial lactate) was performed. The sources of sepsis were identified by various body fluid cultures, including sputum, blood, serous effusion and cerebrospinal fluid. The final diagnoses were made by the attending physicians who were unaware of the research result.

Definitions

The diagnostic criteria of sepsis and septic shock were based on the International Consensus on the Definition of Sepsis and Septic Shock 3.0 published in 2016.4

Blood samples and laboratory analysis

Blood samples were collected at the time of inclusion. Sodium citrate tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) were used for the HBP test using the Axis-Shield HBP microtitre plate ELISA (Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK).6 Coagulant tubes with a silica clot activator, polymer gel, silicone-coated interior (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) were used to evaluate PCT and CRP levels. PCT levels were detected by enzyme-linked fluorescent immunoassay (bioMérieux, Marcy, France) and CRP levels were measured by latex immunoturbidimetry (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois, America) (detection limit, 0.05 ng/mL). These blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min immediately, and separate aliquots of the plasma supernatants were stored at −80°C until analysis. Plastic whole blood tubes with spray-coated K2EDTA (Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK) stored whole blood for cell counting detected within an hour.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software system V.22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and GraphPad Prism V.6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) were used for statistical calculations. Continuous variables were presented as medians (IQR), and categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Levels that could not be detected were assigned values equal to the lower detection limit of the test. Comparison between two groups was performed using independent sample T test. Comparison of multiple groups was performed using single-factor analysis of variance, among which each two comparisons was analysed by Tamhane’s T2 method when the variance showed disorder. χ2 test was used to analyse categorical variables. Areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUCs) were calculated to assess the diagnostic power of each marker. The optimal cut-off value was determined when the Youden Index reached the maximum value. All probabilities were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was regarded as significantly different.

Patient and public involvement

The study was designed to compare HBP, PCT and CRP, and other biomarkers for sepsis and septic shock diagnosis. No patients were involved in the design of the survey, recruitment and conduct of the study. No patients were asked for advice on interpretation or writing of the results. There are no plans to disseminate the findings to study participants.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

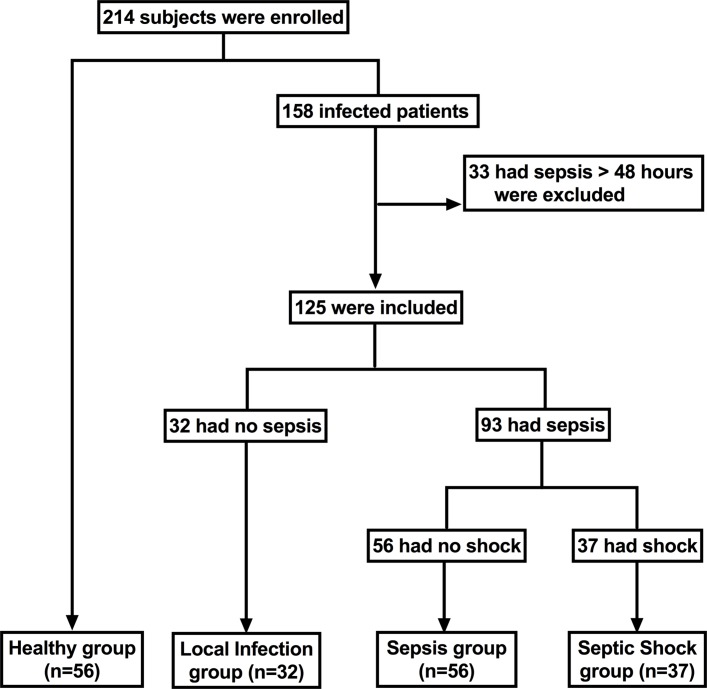

A total of 158 patients with suspected sepsis and 56 physical health examination personnel were enrolled. After retrospective review of complete patient charts, laboratory tests, microbiological tests, and considering the half-life of these biomarkers and the validity of the detection time window,9–11 33 patients (15.4%) diagnosed with sepsis or septic shock for more than 48 hours were excluded. According to the health status and severity of illness, the research subjects were divided into the healthy group (n=56), local infection group (n=32), sepsis non-shock group (referred to as sepsis group) (n=56) and septic shock group (n=37) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients in the study cohort.

The patients diagnosed with sepsis (including non-shock and shock) (n=93) mainly came from the hospital intensive care unit (76/93), while the others came from the wards. The aetiologies of sepsis were different: some had predefined foci and single-culture organisms, while others had multiple or undetermined foci and multiple organisms. Organism culture was performed: 33 patients were found to have Gram-positive organisms and 24 patients were found to have Gram-negative organisms. Additionally, three patients had multiple infections. Most patients had blood cultures (83/93), but only a few had positive results (20/83). All patients with sepsis received antibiotics, 74% (69/93) were treated with steroids and 83% (77/93) had been treated with vasopressors for more than 12 hours before the blood sample was taken. Three patients had used heparin 5 days earlier, three for a week earlier for sampling.

These patients (with local infection, sepsis or septic shock), who mainly had abdominal (43.9%, 25%, and 40.5%, respectively) and respiratory tract (3.1%, 26.8% and 27%, respectively) infections were principally infected with bacteria. However, some patients did not exhibit exact pathogen evidence. There was no significant difference in gender among these groups. The mean sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment (SOFA) score at enrolment was 6.0 in patients with sepsis and 7.0 in those with septic shock; the 28-day mortality rates were 23.2% and 64.8%, respectively. Both the SOFA Score and 28-day mortality rates were higher in patients with septic shock than in those with sepsis. The baseline characteristics of the study populations are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic (n) | Healthy (n=56) | Infection (n=32) | Sepsis (n=56) | Septic shock (n=37) | P values |

| Age, median (IQR) | 62 (54–67) | 59 (52–66) | 70 (56–78) | 70 (59–78) | |

| Gender, % male | 67.9 | 71.9 | 66.1 | 75.6 | >0.05 |

| SOFA Score | 0 | 1 (0–3) | 6 (4–7) | 7 (6–9) | <0.001 |

| 28-d mortality (n [%]) | 0 | 0 | 13 (23.2) | 24 (64.8) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | 3 (9.4) | 7 (12.5) | 2 (5.5) | |

| NYHA I/II | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| NYHA III/IV | 0 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Respiratory disease | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.1) | 15 (26.8) | 10 (27) | |

| Liver disease | 0 | 3 (9.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Child A | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Child B | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Child C | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Renal disease | 5 (8.9) | 2 (6.2) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Need haemodialysis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| No haemodialysis | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal disease | 14 (25) | 14 (43.9) | 14 (25) | 15 (40.5) | |

| Operation | 0 | 1 | 13 | 15 | |

| No operation | 14 | 13 | 1 | 0 | |

| Gynaecological disease | 6 (10.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Encephalopathy | 3 (5.4) | 2 (6.2) | 5 (8.9) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Malignancy | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Other* | 15 (26.8) | 5 (15.6) | 9 (16) | 2 (5.4) | |

| No comorbidities | 12 (21.4) | 1 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Aetiological agent, n (%) | |||||

| Gram-positive bacteria | 0 | 9 (28.2) | 17 (30.4) | 16 (43.2) | |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 0 | 7 (21.8) | 14 (25) | 10 (27) | |

| Virus | 0 | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | |

| Other microorganism† | 0 | 4 (13) | 4 (7.1) | 0 | |

| Culture-negative infection‡ | 0 | 10 (31) | 19 (33.9) | 10 (27) | |

| Polymicrobial infection | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 1 (2.8) | |

| No infection | 56 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blood cultures, n (%) | |||||

| Obtained | 0 | 5 (15.6) | 52 (92.9) | 31 (83.8) | |

| Positive | 0 | 0 | 9 (17.3) | 11 (35.4) | |

*Including diabetes, autoimmune disease, thyroid nodule and polyp of the vocal cord.

†Including Mycoplasma pneumoniae and mould pneumoniae.

‡Including chest radiography-positive pneumonia and fever of unknown origin with inflammatory markers elevated.

NYHA, New York Heart Association Functional Classification; SOFA, sequential [sepsis-related] organ failure assessment score.

Plasma levels of HBP, PCT, CRP, WBC, lactate and polymorphonuclear (PMN), as well as the SOFA Score at enrolment

The plasma levels of HBP, CRP, PCT, lactate and blood cells, as well as the SOFA Score, were analysed. At enrolment, the HBP level of the septic shock group was significantly higher than that of the other groups. The HBP level of the sepsis group was significantly higher than that of the normal local infection group. Compared with the healthy control group, the plasma level of HBP in the local infection group was also significantly increased (figure 2A). Similar to the HBP level, the PCT level and SOFA Score in patients with septic shock were significantly higher than those in the other groups and were obviously higher in patients with sepsis than in those with normal local infection. CRP was dramatically increased in patients with sepsis; however, no apparent difference was found between sepsis and septic shock. The numbers of WBCs and neutrophils were higher in the infection group than in the healthy group. Nevertheless, no obvious difference was found between local infection and sepsis (figure 2B–F). The plasma lactate levels in patients with septic shock were obviously higher than in patients with sepsis. Additionally, the specific data are presented in table 2.

Figure 2.

Plasma levels of HBP, PCT, CRP, WBC and neutrophils, as well as the SOFA Score, at enrolment. Each dot represents the HBP level (A), PCT level (B), SOFA Score (C) in an individual plasma sample at enrolment. (D–F) show the CRP level (D), WBC count (E) and neutrophil count (F) at enrolment among the healthy group, local infection group, sepsis (non-shock) group and septic shock group. Single-factor analysis was used for comparisons the differences among the indicators of the four groups, each two comparisons using Tamhane’s T2 method, and p values are given. Comparison between the survival and non-survival groups using independent sample T test. Star symbols indicate a significant difference, * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p<0.01. CRP, C reactive protein; HBP, heparin-binding protein; PCT, procalcitonin; WBC, white blood cell.

Table 2.

Laboratory measurements and SOFA Score at enrolment

| Healthy (n=56) |

Infection (n=32) |

Sepsis (n=56) |

Septic shock (n=37) |

|

| HBP (ng/ml) | 4.2 (2.8–6.2) | 11.8 (3.5–24.3) | 49.7 (31.9–95.9) | 153.8 (70.9–238.5) |

| PCT (ng/ml) | 0.05 | 0.15 (0.05–1.98) | 3.75 (1.28–8.07) | 4.50 (1.75–27.00) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.0 (1.0–2.1) | 118.2 (73.8–164.1) | 162 (102.6–200.7) | 181.5 (129.7–260.2) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | / | / | 1.24 (0.66–1.67) | 4.72 (3.09–6.35) |

| SOFA Score | 0 | 1 (0–3) | 6 (4–7) | 7 (6–9) |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.0 (4.9–6.8) | 11.6 (6.4–15.4) | 11.5 (9.4–14.9) | 10.8 (7.3–18.0) |

| PMN (109/L) | 4.3 (3.7–5.1) | 10.2 (5.2–13.1) | 9.7 (7.8–13.3) | 9.1 (6.3–16.3) |

CRP, C reactive protein; HBP, heparin-binding protein; PCT, procalcitonin; PMN, polymorphonuclear; WBC, white blood cell.

There were partial missing values on the lactate measurement in the healthy and the local infection group, so we using "/" instead.

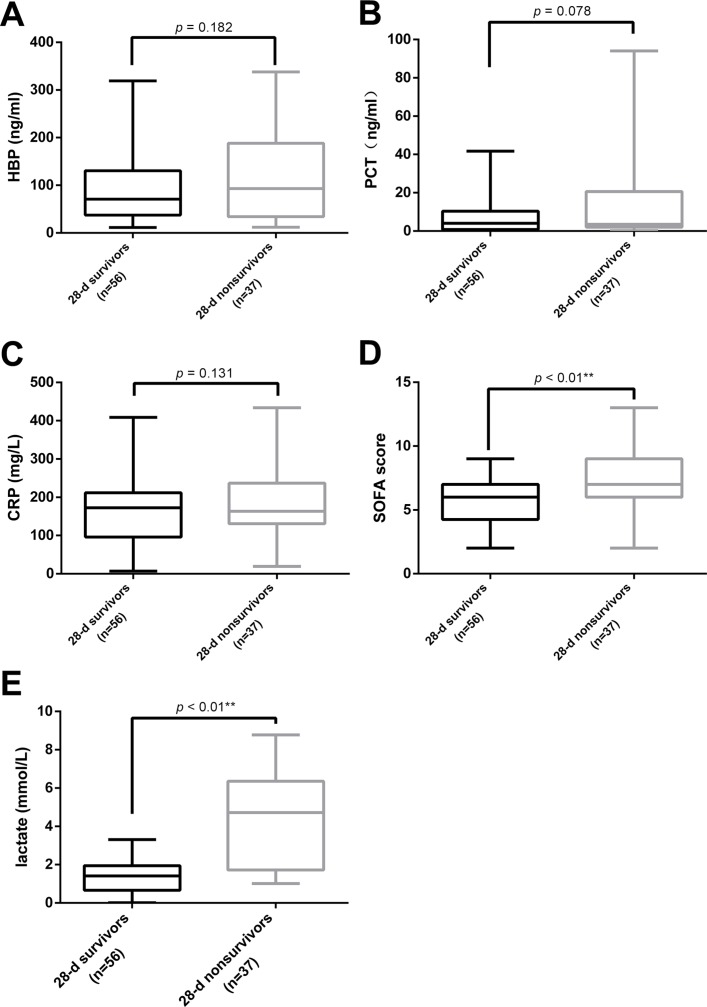

A total of 93 patients with sepsis (56 without shock and 37 with shock) were divided into two groups according to their survival after 28 days: 28-d survivor group (n=56) and 28-d non-survivor group (n=37). No difference was found in the plasma levels of HBP, PCT and CRP between surviving and non-surviving patients with sepsis (figure 3A–C). Nonetheless, the SOFA Score and lactate level of the 28-d non-survivor group was dramatically higher than those of the survivor group, respectively (6.0 vs 7.0 and 1.41 mmol/L vs 4.72 mmol/L) (figure 3D,E).

Figure 3.

Plasma levels of HBP, PCT, CRP and lactate, as well as the SOFA score, and the 28-d survival. (A–E) display the HBP level (A), PCT level (B), CRP level (C), SOFA score (D) and lactate level (E) at enrolment between the survival and non-survival groups in 93 patients with sepsis. CRP, C reactive protein; HBP, heparin-binding protein; PCT, procalcitonin.

Among the 125 infected patients, 86 had clear evidence of pathogens, including 42 with Gram-positive bacteria and 31 with Gram-negative bacteria. There was no significant difference in the plasma HBP levels between patients with Gram-positive bacterial infection and those with Gram-negative bacterial infection (p=0.371).

Plasma levels of HBP, PCT and CRP, as well as the SOFA score, for sepsis and septic shock diagnosis

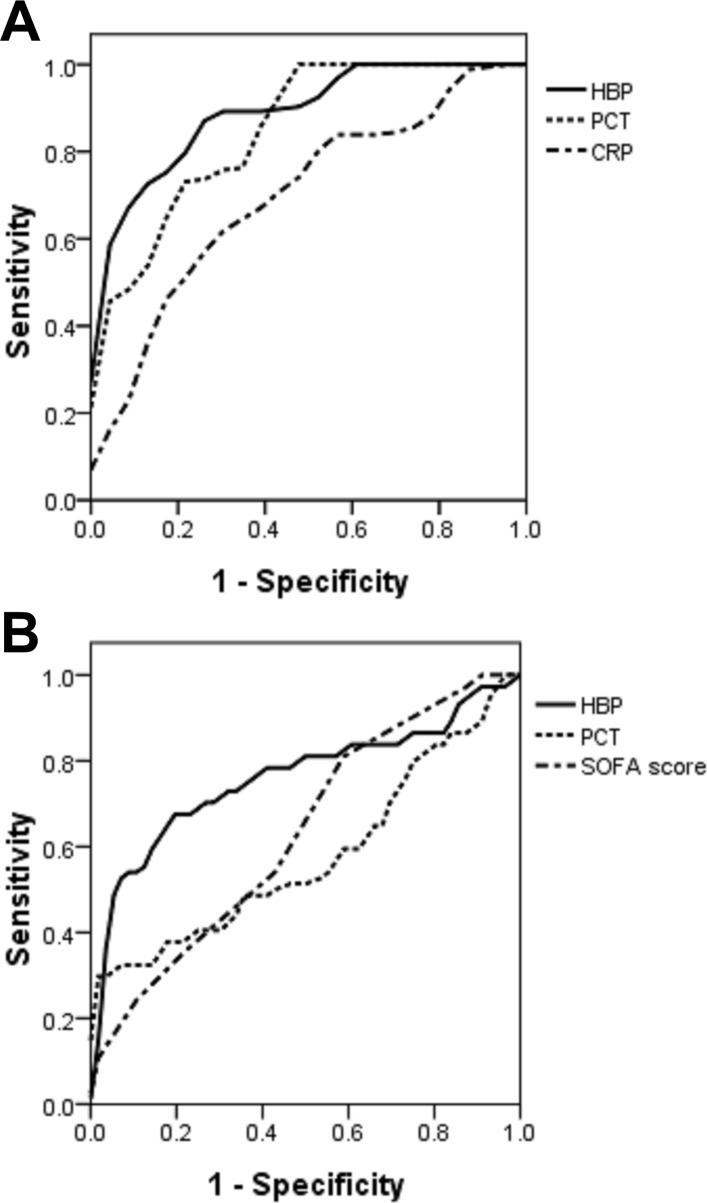

ROC curve analysis was used to evaluate the value of different biomarkers to identify the disease status. In the ROC for diagnosing sepsis from infected people, AUC of HBP was 0.893 (figure 4A), and the optimal cut-off value was HBP≥28.1 ng/mL, giving a sensitivity of 84.9%, a specificity of 78.3%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 94.0% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 65.9% in diagnosing sepsis. These values exceeded those for the other tested markers. The second best probe was the PCT level with an AUC of 0.856 (table 3).

Figure 4.

Plasma levels of HBP, PCT and CRP, as well as the SOFA Score, for sepsis and septic shock diagnosis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of HBP, PCT and CRP levels for diagnosing sepsis in infected people. (A) The area under the ROC curve (AUC) of HBP was 0.893, that of PCT was 0.856 and that of CRP was 0.699. (B) ROC curves for HBP, PCT and the SOFA Score for diagnosing septic shock in patients with sepsis. The AUC of HBP was 0.760, and the SOFA Score was 0.656. PCT cannot identify shock (p=0.195). CRP, C reactive protein; HBP, heparin-binding protein; PCT, procalcitonin.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of the tested variables in diagnosing sepsis from infected patients

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

AUC | AUC 95% CI | P values | |

| HBP (ng/ml) | ≥28.1 | 84.9 | 78.3 | 94.0 | 65.9 | 0.893 | 0.830 to 0.957 | 0.000 |

| PCT (ng/ml) | ≥2.05 | 70.9 | 82.6 | 84.6 | 42.6 | 0.856 | 0.770 to 0.943 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/L) | ≥151.9 | 60.2 | 73.9 | 82.3 | 35.1 | 0.699 | 0.583 to 0.816 | 0.003 |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CRP, C reactive protein; HBP, heparin-binding protein; NPV, negative predictive value; PCT, procalcitonin; PPV, positive predictive value.

In the ROC curve for diagnosing septic shock from patients with sepsis, the HBP level was also the best probe with an AUC value of 0.760 (figure 4B). A cut-off level for the HBP level of ≥103.5 ng/mL gave a sensitivity of 67.6%, a specificity of 82.1%, a PPV of 71.4% and an NPV of 79.3% in diagnosing septic shock. The second best was the SOFA score with an AUC of 0.656. The PCT level cannot identify septic shock (p=0.195) (table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of tested variables in diagnosing septic shock from patients with sepsis

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

AUC | AUC 95% CI | P values | |

| HBP (ng/ml) | ≥103.5 | 67.6 | 82.1 | 71.4 | 79.3 | 0.760 | 0.651 to 0.869 | 0.000 |

| SOFA score | ≥5.5 | 83.8 | 41.1 | 48.4 | 79.3 | 0.656 | 0.545 to 0.767 | 0.011 |

| PCT (ng/ml) | ≥22.15 | 29.7 | 98.2 | 91.6 | 67.9 | 0.580 | 0.453 to 0.706 | 0.195 |

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; HBP, heparin-binding protein; NPV, negative predictive value; PCT, procalcitonin; PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion

Sepsis 3.0 is based on a change in the understanding of its pathogenesis that emphasises the primacy of the non-homoeostatic host response to infection, potential lethality that is considerably greater than a straightforward infection, and the need for urgent recognition. In Sepsis 3.0, septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis in which particularly profound circulatory, cellular and metabolic abnormalities are associated with a greater risk of mortality than with sepsis alone. In this study, we applied the Sepsis 3.0 evaluation criteria4 and found that the plasma HBP level was significantly higher in patients with sepsis than in those with local infections. A cut-off value of HBP ≥28.1 ng/mL gave a sensitivity of 84.9% in diagnosing sepsis and a specificity of 78.3%. Six patients were diagnosed with sepsis 24 hours after sampling and four (67%) of them had a higher plasma HBP level (>24.5 ng/mL). This value was close to that in previous studies which identified severe sepsis with optimal cut-off values of HBP ≥15 ng/mL and ≥30 ng/mL.7 12 HBP has a higher value than the other investigated parameters in the identification of sepsis. HBP can increase capillary permeability, leading to endovascular liquid penetrant clearance and reduction of the effective circulating blood volume. These pathological processes are the important basis of septic shock.13 We also found that HBP level was higher in patients with septic shock than in those with sepsis non-shock. Linder et al performed serial HBP measurements in patients with sepsis before they developed septic shock and found that plasma HBP levels in patients with septic shock were obviously higher than in those with sepsis non-shock between 12 hours and 24 hours.3 HBP is strongly involved in the pathophysiology of sepsis and septic shock, representing a potential diagnostic marker and a target for treatment.14

In our study, among non-sepsis patients whose HBP level was greater than 28.1 ng/mL (six cases), three (50%) cases were diagnosed as aortic dissection with pulmonary infection, which comprises arterial dissection, activation of the coagulation system and elevated fibrinogen levels, causing leucocytes to release leukotriene B4, which binds to the BLT1 receptor on the surface of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and activates the intracellular phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling pathway to release HBP.15 Interestingly, among patients with sepsis without shock but with HBP >103.5 ng/mL (n=10), five (50%) were diagnosed with acute pancreatitis (biliary acute pancreatitis/hyperlipidaemic acute pancreatitis) complicated with abdominal cavity infection. All the patients were in the acute phase of the disease, during the strongest inflammatory response, when HBP acts as a chemoattractant to recruit more leucocytes to the site of local infection, enhancing the activation of monocytes, improving the phagocytosis of macrophages and increasing the pathogen-elimination effect.16 17

Neutrophils are considered the main source of HBP, and transient leucopenia is a relatively common feature of sepsis,18 possibly leading to the HBP level not being increased in patients with sepsis. The ratio of HBP (ng/mL)/WBC (109/L) was evaluated in a previous study, where a ratio >2 indicates an increased risk of sepsis.12 In our data, there were five cases of patients with sepsis with leucopenia (WBC <4 ×109/L). Among these cases, the HBP level of three patients was lower than the cut-off value (28.1 ng/mL), but all of them had an HBP/WBC ratio >2. Unsurprisingly, using the HBP/WBC ratio increased the sensitivity of diagnosing patients with transient leucopenia. Considering that heparin can inhibit the activity of HBP,19 the metabolism characteristics of heparin in the body also determined that the heparin elimination half-life varies with the dose. The half-life of heparin after intravenous injection is 1–6 hours, with an average of 1.5 hours. Therefore, we excluded individuals who had used heparin within 3 days at the time of enrolment. Although studies have confirmed that heparin affects the activity and measurement results of HBP, there is no clear research to prove the time-limiting node of heparin on HBP. Previous studies have confirmed that Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro, simvastatin and tezosentan20–22 can interfere with the release of HBP and that aprotinin23 can also inhibit the activity of HBP. These may affect the measurement of HBP. The patients enrolled in this study have not been treated with related drugs. Additionally, attention should be paid to the effect of therapeutic drugs on the detection value of clinical indicators in relevant studies.

In this study, we found no statistical relationship between the HBP level and the 28-day mortality among septic patients. Some previous studies13 have shown similar results, while others3 23 have not. HBP expression may result in the aggravation or enhancement of the host immune response and progression of the disease.6 However, HBP has been shown to increase the survival rate of cultured monocytes and protect them from oxidative stress.24 25 Treated endothelial cells also showed higher survival rates in apoptosis experiments, suggesting that HBP may play a protective role in the inflammatory response.26 Alternatively, the HBP levels could be underestimated in more severe disease. For example, haemodilution due to high fluid administration, leakage into the extravascular space and urine or increased uptake at sites of inflammation may decrease the plasma levels of HBP in patients with more severe disease.13 With the development of methodology, immunofluorescence can also be applied to HBP detection, which is less time-consuming and easier to handle than ELISA.

Our study includes different disease statuses in the population and comparison with many biomarkers on the same patients and during the same period, and the samples were tested by the same laboratory using the same batch of reagents. Moreover, our diagnostic criteria are up to date with Sepsis 3.0. However, this is a single-centre non-consecutive study; our experimental data were obtained at one point in time, and there were no serial measurements. Most of the patients with sepsis were from the intensive care unit and had been given antibiotics before admission; consequently, we did not assess the influence of antimicrobial therapy on the analysed biomarkers.

Conclusions

We found that, as a potential diagnostic tool, an elevated level of HBP in plasma is associated with sepsis and septic shock, and the HBP level was a potential diagnostic marker in patients with suspected sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study and their families. The authors also thank all doctors, nurses and support staff in their hospital for their indefatigable work on assisting patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: XX and JZ performed the HBP analysis, analysed the data and drafted parts of the manuscript. YZ and FL analysed the data and wrote parts of the manuscript. GL and JH participated in the study design and were responsible for including patients and data collection. ZL and YC participated in the study design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Cuthbertson BH, Elders A, Hall S, et al. . Mortality and quality of life in the five years after severe sepsis. Crit Care 2013;17:R70 10.1186/cc12616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Linder A, Fjell C, Levin A, et al. . Small acute increases in serum creatinine are associated with decreased long-term survival in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1075–81. 10.1164/rccm.201311-2097OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linder A, Åkesson P, Inghammar M, et al. . Elevated plasma levels of heparin-binding protein in intensive care unit patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care 2012;16:R90 10.1186/cc11353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. . The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pieri G, Agarwal B, Burroughs AK. C-reactive protein and bacterial infection in cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol 2014;27:113–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tapper H, Karlsson A, Mörgelin M, et al. . Secretion of heparin-binding protein from human neutrophils is determined by its localization in azurophilic granules and secretory vesicles. Blood 2002;99:1785–93. 10.1182/blood.V99.5.1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher J, Linder A. Heparin-binding protein: a key player in the pathophysiology of organ dysfunction in sepsis. J Intern Med 2017;281:562–74. 10.1111/joim.12604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linder A, Arnold R, Boyd JH, et al. . Heparin-Binding Protein Measurement Improves the Prediction of Severe Infection With Organ Dysfunction in the Emergency Department. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2378–86. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brunkhorst FM, Heinz U, Forycki ZF. Kinetics of procalcitonin in iatrogenic sepsis. Intensive Care Med 1998;24:888–9. 10.1007/s001340050683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takata S, Wada H, Tamura M, et al. . Kinetics of c-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A protein (SAA) in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), as presented with biologic half-life times. Biomarkers 2011;16:530–5. 10.3109/1354750X.2011.607189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beran O, Herwald H, Dzupová O, et al. . Heparin-binding protein as a biomarker of circulatory failure during severe infections: a report of three cases. Scand J Infect Dis 2010;42:634–6. 10.3109/00365541003754477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Linder A, Christensson B, Herwald H, et al. . Heparin-binding protein: an early marker of circulatory failure in sepsis. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:1044–50. 10.1086/605563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chew MS, Linder A, Santen S, et al. . Increased plasma levels of heparin-binding protein in patients with shock: a prospective, cohort study. Inflamm Res 2012;61:375–9. 10.1007/s00011-011-0422-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Linder A, Soehnlein O, Akesson P. Roles of heparin-binding protein in bacterial infections. J Innate Immun 2010;2:431–8. 10.1159/000314853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hui ST1, Andres AM, Miller AK, et al. Txnip balances metabolic and growth signaling via PTEN disulfide reduction. 3921-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:3921–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soehnlein O, Lindbom L. Neutrophil-derived azurocidin alarms the immune system. J Leukoc Biol 2009;85:344–51. 10.1189/jlb.0808495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holub M, Beran O. Should heparin-binding protein levels be routinely monitored in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock? Crit Care 2012;16:133 10.1186/cc11379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Funke A, Berner R, Traichel B, et al. . Frequency, natural course, and outcome of neonatal neutropenia. Pediatrics 2000;106(1 Pt 1):45–51. 10.1542/peds.106.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCabe D, Cukierman T, Gabay JE. Basic residues in azurocidin/HBP contribute to both heparin binding and antimicrobial activity. J Biol Chem 2002;277:27477–88. 10.1074/jbc.M201586200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McAuley DF, O’Kane CM, Craig TR, et al. . Simvastatin decreases the level of heparin-binding protein in patients with acute lung injury. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:47 10.1186/1471-2466-13-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Persson BP, Halldorsdottir H, Lindbom L, et al. . Heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37) - a link to endothelin-1 in endotoxemia-induced pulmonary oedema? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014;58:549–59. 10.1111/aas.12301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gautam N, Olofsson AM, Herwald H, et al. . Heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37): a missing link in neutrophil-evoked alteration of vascular permeability. Nat Med 2001;7:1123–7. 10.1038/nm1001-1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin Q, Shen J, Shen L, et al. . Increased plasma levels of heparin-binding protein in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2013;17:R155 10.1186/cc12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pereira HA, Shafer WM, Pohl J, et al. . CAP37, a human neutrophil-derived chemotactic factor with monocyte specific activity. J Clin Invest 1990;85:1468–76. 10.1172/JCI114593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shrotri MS, Kuhn JF, Peyton JC, et al. . Heparin-binding protein decreases apoptosis in human and murine neutrophils. J Surg Res 2000;89:53–9. 10.1006/jsre.1999.5803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edens HA, Parkos CA. Neutrophil transendothelial migration and alteration in vascular permeability: focus on neutrophil-derived azurocidin. Curr Opin Hematol 2003;10:25–30. 10.1097/00062752-200301000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.