Abstract

Objective

To review systematically the evidence on how deinstitutionalisation affects quality of life (QoL) for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Design

Systematic review.

Population

Adults (aged 18 years and over) with intellectual disabilities.

Interventions

A move from residential to community setting.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Studies were eligible if evaluating effect on QoL or life quality, as defined by study authors.

Search

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, CINAHL, EconLit, Embase and Scopus to September 2017 and supplemented this with grey literature searches. We assessed study quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme suite of tools, excluding those judged to be of poor methodological quality.

Results

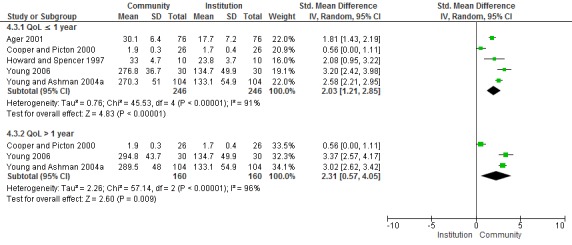

Thirteen studies were included; eight quantitative studies, two qualitative, two mixed methods studies and one case study. There was substantial agreement across quantitative and qualitative studies that a move to community living was associated with improved QoL. QoL for people with any level of intellectual disabilities who move from any type of institutional setting to any type of community setting was increased at up to 1 year postmove (standardised mean difference [SMD] 2.03; 95% CI [1.21 to 2.85], five studies, 246 participants) and beyond 1 year postmove (SMD 2.34. 95% CI [0.49 to 4.20], three studies, 160 participants), with total QoL change scores higher at 24 months comparative to 12 months, regardless of QoL measure used.

Conclusion

Our systematic review demonstrated a consistent pattern that moving to the community was associated with improved QoL compared with the institution. It is recommended that gaps in the evidence base, for example, with regard to growing populations of older people with intellectual disability and complex needs are addressed.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018077406.

Keywords: quality of life, intellectual disabilities, deinstitutionalisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted an extensive systematic search of academic databases, using two reviewers to assess eligibility independently.

Eligible quantitative and qualitative studies were required to meet a minimum quality threshold.

We excluded studies not reporting ethical approval, which minimises bias and improves quality standards but potentially excludes earlier studies conducted without reporting guidelines.

We did not include static cross-sectional studies, requiring that studies evaluated a move in residence for a person with intellectual disability.

The search strategy is greater than a year old, and further research might be available that would contribute to the review.

Introduction

Background/rationale

The right to live independently in a place of one’s own choosing reflects the guiding principles of the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.1 A process of ‘deinstitutionalisation’ - that is, moving people with disabilities and mental health problems from institutions to community-living arrangements that support autonomous decision-making and full participation in society - has occurred at different times and different speeds since the 1960s in Scandinavia, the UK, USA, Canada and Australia.2

We undertook a systematic review of the evidence on deinstitutionalisation for people with intellectual disabilities (ID). We examined specifically the effect of deinstitutionalisation on economic outcomes and on quality of life (QoL). In this paper we report the results for the QoL studies. The economics results, as well as further details on our search strategy, are available in a companion paper.3

QoL is a priority outcome measure for policy-makers but measurement is challenging due to the fluidity of definitions and variability in applications of the concept in practice.4 5 The Schalock framework of QoL is the most widely accepted within the field, with its eight core components of emotional well-being, interpersonal relations, material well-being, personal development, physical well-being, self-determination, social inclusion and rights.6 Research to date highlights that people with ID persistently score lower on QoL measures than the general population,7 and that level of ID, environmental factors and the level and nature of supports received can impact QoL for people with ID.7–9 Tracking outcomes, including QoL outcomes, for people with ID following deinstitutionalisation encounters measurement challenges both in the gathering of self-report, proxy and family data and in the value placed on each type of report.6 10–15 These issues are particularly challenging when engaging people with severe/profound ID yet inclusion of these subgroups is essential.16

The impetus for deinstitutionalisation arises from, inter alia, concerns about standards of care, poor outcomes and the recognition that people with ID were being unnecessarily deprived of ordinary lives.17 18 Research alludes to positive benefits of smaller community-based settings19 20 but also attests that gains in health and other outcome measures are not inevitable.19 In addition, improvements recorded shortly after a move may plateau after 1 year.21 The lack of community readiness to support people to live in the new setting has been proposed as a reason for poor outcomes. The primary focus of policy is on the closure of institutions rather than preparing the community to meet the needs of people with disability now living in the community.22 A reduction in the size of setting that the individual moves to cannot be assumed to result automatically in better outcomes in terms of health, well-being and overall QoL. This is particularly the case if the new community setting mirrors the culture and practices of the larger institutions with change in how people live, as well as how, when and what type of supports received, being minimal or not materialising.23 24

Given the lack of consensus on QoL outcomes as a consequence of deinstitutionalisation there is a need to consolidate the available evidence. This is particularly important in the context of countries that have recently begun or plan to begin implementing a policy of deinstitutionalisation. It is also important for countries that may be challenged by the sustainability and maintenance of the community models put in place in the context of coming demographic change. This is both in terms of the growing older cohort of the general population, which includes the ageing parents and siblings of people with ID, and the increased longevity of people with ID themselves.

Objectives

To review systematically the evidence on how deinstitutionalisation affects QoL for adults with ID.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies reporting on PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes and Study types) or PEOS (Participants, Exposure, Outcomes and Study types) were eligible for this review. While cross-sectional quantitative studies were generally excluded, as they lacked comparative data on a move, it was not by rule. For example, if a study cross-sectionally asked study participants after a move about changes in QoL arising from that move, this would be included. However, studies that cross-sectionally compared QoL for groups living in institutional and community settings without either group having moved were excluded. Only papers published in English language were eligible.

Types of participants

Adults (aged 18 years and over) with ID.

Types of intervention/exposure/comparators

Our intervention of interest was deinstitutionalisation—that is, a residential move from an institutional to a community setting.

We did not define institutional and community settings ex ante, since no widely accepted definitions (eg, according to the number of residents per unit) exist and we did not want to exclude arbitrarily studies of relevance. Additionally, we were conscious that processes of deinstitutionalisation have happened and are happening at different speeds in different countries, sometimes now involving reinstitutionalisation (moving back from the community to an institution) and transinstitutionalisation (moving between institutions).25

Consequently, we assessed the characteristics of institutions and community-living arrangements on the information provided in each paper.

Types of outcomes

Our prespecified primary outcome of interest was ‘QoL’ or ‘life quality’, as defined by study authors. There were no a priori restrictions on the operationalisation of QoL. To be eligible as a primary outcome, we required QoL to be measured both prior to and following a move.

Types of studies/reports

Study designs eligible for inclusion were: prospective/retrospective before and after studies, randomised trials, economic evaluations, qualitative/descriptive and exploratory studies.

Search strategy

Database search

To ensure a search strategy that was both sensitive and specific, a comprehensive search methodology to identify both published and grey (eg, policy reports, national/international guideline documents, etc) literature was developed and executed through routine scientific database searches and grey literature retrieval. Though eligibility was restricted to English language publications, by searching all languages, we were able to identify the extent of potentially eligible additional papers not initially included and assess whether this may have presented a source of possible language bias.

The following electronic databases were searched from date of inception to 11 September 2017: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CENTRAL, CINAHL, EconLit, Embase and Scopus. Search terms used to guide the review were developed and subsequently finalised by an information specialist (GS) in collaboration with the review team topic experts, and by executing ‘scoping’ and pilot searches to cross-reference search terms with prior studies and reviews. A combination of title/abstract keywords and related controlled vocabulary terms were incorporated into the search to ensure comprehensiveness. See online supplementary appendix 1 for details. No eligible study looked at both economics and QoL. We reviewed references of included studies and did not identify further eligible studies for inclusion.

bmjopen-2018-025735supp001.pdf (888.6KB, pdf)

Other sources

The search of grey literature was concerned with non-academic publications, readily available online and included a range of different types of documents such as government, statutory organisation, non-statutory organisation (with particular focus on national disability organisations and university based centres of disability studies) policy, guidance, standards or clinical audit documents which included analytical data—either primary or secondary data analysis. See online supplementary appendix 2 for details.

Study selection and quality assessment

Screening of titles and abstracts

Two reviewers (RLV and EM) screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved citations, independently, based on the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, approximately 600 conflicts were resolved between these two reviewers on the basis of consensus. Discussions were driven by closely referring to inclusion/exclusion criteria to reach consensus. A key discussion point was verifying that a move had taken place and it was not solely a cross sectional study. In the initial screening stage a particular feature was the inclusion of the concept of adaptation which was viewed through consultation with one of the SR’s topic experts not to warrant inclusion as an aspect for QoL. The online reviewer tool COVIDENCE (https://www.covidence.org/) was used to manage the screening process.

Screening of full text reports

Two independent reviewers (RLV and EM) screened the full texts papers independently, with any conflicts or uncertainties resolved in discussion between the two reviewers.

Assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias

Each included study was assessed for methodological quality using one of a group of standardised instruments developed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists). The CASP tool because it has been used previously in reviews, and tools have been developed for the varying study designs. Furthermore all CASP checklists cover the three main areas of validity, results and clinical relevance. A pair of reviewers conducted the quality assessment process whereby one reviewer (RLV or EM) assessed the studies’ methodological quality and a second reviewer (RLV or EM) performed their own rapid assessment to corroborate quality assessments. Any conflicts were resolved through discussion and consensus. Given that studies of low (or poor) methodological quality can lead to overestimates of the effects of interventions or variables under investigation, and can increase the potential for bias in the results, usually in a positive direction, an a priori decision was made to exclude studies assessed as being of low methodological quality (see online supplementary appendix 3).

Guided by the CASP quality assessment tool, studies involving primary data collection that did not demonstrate evidence of informed consent were excluded.

Secondary analyses of anonymised data, typically do not require consent as there is no human participation, were not excluded for failing to demonstrate consent agreement.

Data analyses

Data extraction

Comprehensive data extraction forms were predesigned and piloted to extract relevant data. One reviewer (RLV or EM) extracted the data from the included papers, and a second reviewer (RLV or EM) performed their own rapid assessment of the extracted data to corroborate the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the extracted data. Any conflicts were resolved by discussion and consensus. Relevant data included study design features (randomised trial, prospective or retrospective, etc), study setting (country of origin), participant details (characteristics, numbers, etc), recruitment and sampling, exposure/intervention details, ethical issues (eg, consent), QoL data before and after a move (including summary measures and their SD as well as qualitative themes) and author-identified implications.

Data syntheses

Quantitative studies

We aimed, a priori, to perform a meta-analysis of individual studies’ data to achieve an overall (higher level) effect estimate following a move from an institutional setting to a different/community-based setting on QoL. Inclusion in a meta-analysis required sufficient similarity in design (ie, include prospectively collected premove and postmove data) and had to provide overall QoL measures. Specifically they had to have measured QoL prospectively as a pretest (before the move) and post-test (at least one follow-up time point postmove) measure(s). For studies that used repeated post-test measures, we selected QoL measures at one time point for inclusion in the meta-analysis, to avoid over-counting, and described all other time point results narratively. To further reduce characteristic variances in the meta-analyses, we sub-grouped the data according to follow-up at either up to and including 1 year postmove and at more than 1 year following a move from any type of institutional setting to any type of community setting. In addition, while sub-scales of QoL might be chosen as a proxy measure of overall QoL, to be included in the meta-analyses, an overall QoL scale score had to be provided; where sub-scale results only were provided, we present the results for these narratively. High levels of statistical heterogeneity in the analyses were likely due to elements of clinical variation across the included studies (eg, participants with varying levels of ID across studies, and differing age profiles), rather than study design issues. To counterbalance the anticipated subtle differences across the studies (eg, varying degrees of ID/challenging behaviour, etc), we meta-analysed the data using a random-effects model, rather than a fixed-effects.26 Lastly, because the instruments used to measure QoL across the included studies differed, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) as per recommended meta-analytical methods.26 We interpreted the results as an average of the effect of a move from an institutional setting to a community setting, rather than a ‘best-estimate’ of the effect, as provided by a fixed-effect model. Studies not meeting these similarity criteria, are reported narratively.

Studies not meeting these similarity criteria, are reported narratively.

Qualitative studies

We employed a thematic narrative synthesis for identified qualitative studies and the qualitative elements of mixed methods studies.27

Patient and public involvement

The National Disability Authority of Ireland,28 an independent state body that advises government and the public sector on policy and practice, contributed to the search strategy.

Results

Search and selection results

Database search

The database search for both cost and QoL studies identified 25 853 citations for consideration against the eligibility criteria for the review. Following removal of duplicates (n=6568), 19 000 citations were excluded on title and abstract, as they clearly did not meet the review’s prespecified eligibility criteria (figure 1). A full-text review of the remaining 285 citations was performed, following which a further 217 were excluded and 32 were unobtainable. Reasons for exclusion were: no examination of a change in residential setting (127 articles), no cost or author-defined QoL as an outcome (46), opinion or commentaries and reviews (18), not in English language (12), not an adult population with ID (8) and miscellaneous (6).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for QoL search. ID, intellectual disability; QoL, quality of life.

Thirty-six articles were therefore identified as meeting the eligibility criteria, of which 21 were subsequently excluded following an assessment of their methodological quality using the CASP tool. Reasons for exclusion at quality assessment included no report of establishing consent of study participants, and insufficient and negligible data on participants and/or outcomes (see online supplementary appendix 3 for a list of studies excluded after quality assessment). Of the 15 studies remaining, two addressed economic outcomes only and are included in a separate paper.3 No eligible study looked at both economics and QoL. Thirteen QoL studies passed quality assessment; eight quantitative studies, two qualitative, two mixed methods studies and one case study (online supplementary appendix 4).

Grey literature search

A total of 74 specific reports were identified from the grey literature search. Following detailed review, 30 reports were identified as relevant to deinstitutionalisation from a cost and/or QoL perspective. Of these, six include data on premove and postmove measures and so were eligible for this review. Following a quality assessment of each of the six reports that met the eligibility criteria and focused on premove/postmove, none of the reports were included in the final analysis. See online supplementary appendix 2 for details.

Main results

Description of included studies

Of the 13 included QoL studies, eight were quantitative,29–36 two were qualitative,37 38 two were mixed methods studies39 40 and one was a case study.41

Characteristics of included studies are summarised in table 1. Sample size ranged from 1 to 76 persons and publication year was from 1994 to 2015. All studies originated from high-income countries, where deinstitutionalisation has been well established in policy and implemented, with six studies originated in Australia, four in the UK, two in Ireland and one in New Zealand. Of the six from Australia, two report different analyses of the same sample and these were dealt with in unison where it was more meaningful to do so.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies on quality of life

| Study | Location | Aim | Study design | Participants | Premove setting | Postmove setting | Quality of life tool or proxies | ||

| Description | No in institution | Description | No moving to community | ||||||

| Ager et al 29 | UK | To examine levels of social integration for individuals resettling into community provision following the phased closure of Gogarburn Hospital, Edinburgh, UK, and the personal and service-related characteristics which were influential on such integration. | Prospective cohort. Pre–post. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 6–9 months. |

Total sample=76. Age: mean=53 years (range: 21–92). Gender: not reported. Intellectual disability (ID) level: not reported. Time in institution: 1–66 years. Health status: not reported. |

One hospital | 76 | 19 community-based homes (18 voluntary funding, one private), OR one of two nursing homes (private), OR one of five older people’s homes (local authority). | 76 | LEC |

| Barber et al 30 | Australia | To report the immediate effects of relocation on those clients who were relocated during the first year of the (deinstitutionalisation) project. | Prospective cohort. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 1 month. |

Total sample=15. Age: mean=42.4 years (range 30–57, SD 8.51). Gender: eight females, seven males. ID level: mild=8, moderate=6, severe=1. |

One institution | 15 | Community-based group homes. | 15 | QoL-Q |

| Bigby40 | Australia | To examine changes in the nature of the informal relationships of residents 5 years after leaving an institution. | Mixed methods. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 1, 3 and 5 years. |

Total sample=24. Age: mean=51.5 years (range 39–68). ID level: mild=0, moderate=15, severe or Profound=6, unknown=3. Identified health issues=17, psychiatric diagnosis=7, mobility impairment=6. Some residents had more than one health issue. Time in institution prior to move: age: mean=38 years, (range 10–54). |

One large institution. | 24 | Small group home houses in the community. | 24 | Analysis of social networks (quantitative), and structure interviews (qualitative). |

| Cooper and Picton31 | Australia | To examine the long-term effects of relocation on a sample of 45 adults with ID who moved from a state residential institution to small group homes and to units within other institutions. | Prospective cohort. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 6 months and 3 years postmove. |

Total sample=45. Group moving to community=26: age: mean=52 years (SD=15.3); gender: 12 female, 14 male ID level: mild=24%, moderate=52%, severe/profound=24%. Group moving to refurbished institution=19: age: mean=55.2 (SD=12); gender: nine female, 10 male; ID level: mild=5%, moderate=47%, severe/profound=47%. The authors report no significant difference between groups in terms of ID level, though no statistics were reported. Health status: not reported. |

One institution—closure order. | 45 | Community group homes housing not more than six people (=26). Refurbished institution (=19). |

26 | QoL-Q |

| Di Terlizzi41 | UK | To describe ‘the life history of a woman with severe learning disabilities and communicative impairment’. | Case study | Total sample=1. Aged 36 when moved to community house. Severe learning disability and challenging behaviour. |

Residential hospital institution. | 1 | Small community staffed house. Shared with three other highly independent cotenants with mild learning disabilities. Service provided 1:1 staff ratio throughout the day. | 1 | Qualitative case study. |

| Golding et al 32 | UK | To evaluate the effects of relocation from institutional to specialised community-based provision for people with severe challenging behaviour. | Prospective cohort (+additional comparison group that already in community—irrelevant here). Premove: baseline. Postmove: 3 months, 9 months. | Total sample=6 males with mild to moderate ID and challenging behaviour. An additional six participants who were already in the community were also included in this study but are not reported on for the purposes of this review. |

Institution operated by the National Health Service. | 6 | Two separate houses managed by a specialist challenging behaviour residential service with an on-duty staffing ratio of four staff to every six residents between 07:00 and 22:00 hours. | 6 | LEC |

| Howard and Spencer33 | UK | To provide local management and staff with some insight into the effect of service changes (move from group home to smaller community settings) on the lives of the residents. | Prospective cohort. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 1 year. |

Total sample=10. Age: mean=61 years. Gender: seven females, three males; who had a preference to remain in a rural setting postmove. |

Large rural group home with institutional features. | 10 | One of two rural community houses. | 10 | LEC |

| Kilroy et al 37 | Ireland | To explore ‘key workers’ perceptions of the impact of a move to community living on the QoL of individuals with an ID’. | Qualitative. Proxy participants. | Eight people with severe ID who had had moved from a residential campus to the community over the past 4 years. Age: mean=37.4 years (range 26–44). Gender: two females, six males. |

One institution. | 8 | Two community houses that are owned by two housing associations set up by family of the individuals and staff of the disability organisation but are run as independent entities. | 8 | Qualitative interviews |

| O’Brien et al 39 | New Zealand |

To investigate the outcomes of the move into community homes for the 61 people who left the psychiatric hospital in 1988, including an exploration of the perceptions of the people who had been deinstitutionalised, their family members and staff about the effects of the move into the community. | Mixed methods. Retrospective cohort. |

Total sample=54. Age: mean=48 years (range=36–65, no SD reported). Gender: 31 females, 23 males; high support needs=41, medium=3, low=10. |

One long stay in hospital. | 54 | Group homes located in the community 1:1 on duty staff ratio to assist with integration. | 54 | Family ratings of quality of changes in quality of life, and qualitative interviews. |

| Sheerin et al 38 | Ireland | To explore whether, and to what extent, the move to the community led to the achievement of individualised and personal outcomes for tenants. In addition, it sought to understand the significance of the move in terms of where tenants had moved from and to examine the extent to which this had resulted in their integration in the local community’. | Qualitative. Proxy participants. | Total sample=7. Age: not reported; Gender: three females, two males; five people with ID two relatives of other tenants. Health status: not reported. |

One institution. | 7 | New residence. The new living unit is located within the commuter belt of Dublin and incorporates a number of self-contained living spaces with shared living areas within staffed houses. |

7 | Qualitative interviews. |

| Young34 | Australia | To ‘monitor changes in skills and life circumstances as residents of an institution that was to be permanently closed were progressively relocated into either dispersed homes in the community or cluster centres and to record any changes in adaptive and maladaptive behaviour, choice-making and objective life quality’. | Prospective cohort. Premove: baseline. Postmove: 12 months, 24 months. |

Total sample=60. Age: (range: 27 to 81). Gender: 22 females, 38 males. ID level: mostly moderate or severe/profound. Two groups of 30 matched post-hoc: demographic, health, impairment, adaptive behaviour variables. |

One institution. | 60 | Cluster centres: accommodating 20–25. 7–8 houses and an admin centre. Outer suburb. Resemble surroundings. Modified as required. Community: pre-existing outer-suburban houses, 2–3 residents. Good description in paper. |

30 | LCQ |

| Young and Ashman35 36 | Australia | To ‘monitor changes in skills and life circumstances as the participants were progressively relocated from an institution to community homes and to record any changes in quality of life that might be considered equivalent to the experiences of others without mental retardation in the community’. | Prospective cohort. Premove: baseline 6 months premove. 1, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months postmove. |

Total sample=104. Age: mean=47 years (range 21–84). Gender: 47 females, 57 males. ID level: 61% severe, 25% moderate, 14% mild. Majority: challenging behaviour, specific health needs or impairments (50 with visual, hearing or mobility impairment), long-term institutionalisation (in many cases most of their lives; 2 to 70 years, mean length of stay=26) |

one institution | 104 | Modern, brick, free-standing, public housing, which was typical of the surrounding neighbourhood in outer suburban areas and had more favourable staff-to-resident ratios. Additional info. In paper. | 104 | LCQ |

LCQ, Life Circumstances Questionnaire; LEC, Life Experiences Checklist; QoL-Q, Quality of Life Questionnaire.

QoL was operationalised in a range of ways, with some consequent diversity in measurement tools. Three studies used the Life Experiences Checklist (LEC),42 a tool which assesses both objective and some more subjective experiences of QoL, and for which validity and reliability data are available. Three studies used the Life Circumstances Questionnaire, a non-standardised tool to assess objective QoL developed by the authors of the studies in which it is used.35 Two studies used the QoL Questionnaire (QoL-Q), a validated tool providing information on subjective and objective QoL.43 Other ways of measuring QoL included aspects of informal social relationships (one study) and family ratings of QoL (one study).

Our quality appraisal assessed risk of bias within studies (online supplementary appendix 4). Of the 13 studies, 12 identified and accounted for important confounding factors. No study was found to have measured exposure or outcome inaccurately, but on these studies we concluded ‘can’t tell’ for seven and three studies respectively.

Five research studies were included which attempted to assess QoL longitudinally, that is, with multiple postmove assessments. Details on follow-up across studies are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Timings of postmove assessments in studies with quantitative quality of life data

| Study | Timing of postmove assessment | ||||||||

| 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months | 9 Months | 1 Year | 1.5 Years | 2 Years | 3 Years | 5–9 Years | |

| Ager et al 29 | Yes * | ||||||||

| Barber et al 30 | Yes | ||||||||

| Bigby40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Cooper and Picton31 | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Golding et al 32 | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Howard and Spencer33 | Yes | ||||||||

| O’Brien et al 39 | Yes | ||||||||

| Young34 | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Young and Ashman35 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Total | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Young and Ashman35 36 are combined in summary tables, as both papers analyse outcomes for the same cohort at the same time points.

*Between 6 and 9 months.

Key findings

Quantitative studies

The key findings of the ten studies with quantitative elements are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative QoL research

| Author (year) | Key findings on quality of life |

| Ager et al (2001)29 | Significant premove/postmove improvements in overall quality of life and on all five of the LEC subscales (all p<0.005). LEC change scores stratified by dependency level: postmove changes greater as dependency level increased, but not statistically significant. |

| Barber et al (1994)30 | No statistically significant change in quality of life 1 month postmove, as measured on four QoL-Q subscales, Satisfaction, Competence/Productivity, Empowerment/Independence and Social Belonging/Integration. Overall quality of life was not investigated. |

| Bigby (2008)40 | Slight, but not statistically significant downward trend from premove to 5 years postmove in the number of residents in contact with family members annually or more frequently (85% [20 individuals] to 75% [18]). Significant drop in the mean number of family members in contact with residents between one and 5 years postmove (p<0.05). Mean informal network size increased from premove to 1 year postmove, but then decreased at 3 years and again at 5 years; the overall decrease was not statistically significant (p>0.05). Reasons cited by family members for changes in/low levels of contact: changing circumstances (eg, ill health or movement for retirement), limited availability of service staff to support family visits, lack of knowledge of a resident’s daily life, frequent staff changes (most frequently cited), being unknown by staff, aggressive behaviour or lack of acknowledgement by the resident when contact was made. Often telephone contact replaced physical visits. The author also cited a lack of specific goals or strategies relating to maintenance of contact in residents individual programme plans, or lack of implementation of same, as a reason for contact with family and friends not being maintained. |

| Cooper and Picton (2000)31 | Significant improvement in quality of life (QoL-Q) at both 6 months and at 3 years following move to the community from a decommissioned institution. A subgroup of 19 individuals who moved to refurbished units in a different institution at also showed significant improvement in overall quality of life at both 6 months and at 3 years following the move. |

| Golding, Emerson, and Thornton (2005)32 | Improvements in overall LEC scores, for a small sample of six with mild to moderate ID and severe challenging behaviour, at both three and 9 months postmove; 49% increase between baseline and 3 months, and a further 24% increase between 3 months and 9 months, and in all five LEC domain scores (Home, Leisure, Freedom, Opportunities, Relationships), and all increases, other than Leisure, were maintained at 9 months postbaseline (p<0.05). |

| Howard and Spencer (1997)33 | Improvement in quality of life overall (LEC) for a small sample of ten moving to rural settings (as was movers’ preference). All domain areas (Home, Leisure, Freedom and Opportunities) except Relationships increased significantly at 1 year postmove compared with premove scores (p<0.01 or p<0.001). |

| O’Brien et al (2001)39 | Quantitative data was provided for a small subsample in this study (11 to 14). Better family ratings of quality of life compared with a 9 year retrospective estimation of quality of life in the institution, across all of the included domains at follow-up (Material Possessions, Health, Productivity, Safety, Place in Community, and Wellbeing). |

| Young (2006)34 | Individuals (with mostly moderate to severe/profound ID) who moved to either small group homes or cluster housing had significantly higher QoL scores at both 12 and 24 months compared with premove in an institution. Those who move to the community also had significantly better outcomes than those who moved to clustered settings at 12 (MD 26.9, 95% CI 1.27 to 52.53) and at 24 months (MD 39.2, 95% CI 14.31 to 64.09) postmove. All QoL sub-domains (material well-being, physical well-being, community access, routines, self-determination, social-emotional well-being, residential well-being, and general well-being) improved significantly with a linear trend from premove to 12 and 24 months for both groups (all p<0.001). Community settings afforded significantly better physical well-being (p<0.005), community access (p=0.001), routines (p<0.01), self-determination (p<0.01), residential well-being (p<0.01) and general life improvements (p<0.001) compared with clustered settings. The groups did not differ on material well-being and social/emotional well-being. |

| Young and Ashman (2004, 2004)35 36 | Improved quality of life, for a sample of 104 people described as having generally higher support needs, at both 12 and 24 months postmove. There was a significant linear increase in QoL scores, but also a significant quadratic trend suggesting a plateauing of QoL scores at 24 months postmove. Overall quality of life experienced by people with mild/moderate ID did not significantly improve following a move to a community setting for people aged 20–39 years or 40–59 years, and showed a non-significant reduction for the 60+ age group. There was a significant increase in overall QoL scores at 24 months postmove for those with severe/profound ID for all three age categories (p<0.01 or p<0.001). Participants with severe/profound ID had lower total QoL scores at both premove and at follow-up, than those with mild/moderate ID. Participants in all three age groups and both levels of ID had increased scores in the following domains: Material Well-being, Physical Well-being, Community Access, Routines, Self-determination, Social/Emotional Well-being, Residential Well-being, and General factors. The only exceptions were lack of significant improvement in physical well-being for the youngest mild/moderate ID group and the oldest severe/profound group. |

ID, intellectual disability; LEC, Life Experiences Checklist; MD, mean difference; QoL-Q, Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Of these, five were deemed suitable for inclusion in a meta-analysis to examine QoL outcomes for people with any level of ID who move from any type of institutional setting to any type of community setting.29 31 33–35 In secondary meta-analyses we performed subgroup analysis by QoL subscale, age and level of ID. In addition, outcomes following a move from one institutional setting to another institutional setting were analysed (two studies).31 34

Overall QoL

Meta-analysis of QoL outcomes for people with any level of ID who move from any type of institutional setting to any type of community setting are presented in figure 2. QoL was significantly increased at up to 1 year postmove (SMD 2.03; 95% CI [1.21 to 2.85], five studies, 246 participants, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) level of evidence: moderate) and beyond 1 year postmove (SMD 2.34. 95% CI [0.49 to 4.20], three studies, 160 participants, GRADE level of evidence: moderate), with total QoL change scores higher at 24 months comparative to 12 months.

Figure 2.

Quality of life with any level of intellectual disability postmove from any institutional setting to any community setting.

Level of ID

Some studies were not disaggregated by level of ID while others provided exact numbers for those with mild, moderate or severe/profound ID. To explore QoL specific to levels of ID, we were able to extrapolate data explicitly on people with mild to moderate ID from four studies,29 32 33 35 of which two were suitable for including in a sensitivity analysis (figure 3).33 36 Overall QoL experienced by people with mild/moderate ID did not significantly improve following a move from an institution to any community setting (mean difference (MD) 0.99, 95% CI [−0.41 to 0.46], two studies, 51 participants).

Figure 3.

Quality of life in people with mild/moderate intellectual disability only postmove.

One study provided data explicitly on a group of people with severe/profound ID.36 These data are also stratified by age (20–39, 40–59, 60+), but using the average mean and SD scores across the three age groups, results demonstrated significantly increased QoL scores at 24 months postmove in this cohort with severe/profound ID (MD 170.1, 95% CI [158.4 to 181.8]; p<0.0001).

One study assessed QoL in a hospital group (n=6) with mild/moderate ID and severe challenging behaviour (baseline data) prior to a move to community houses and again three and 9 months postmove.32 The authors narratively described significant improvements in overall LEC scores (baseline to 3 months, 49% increase; three to 9 months, additional 24% increase increase), and in all five LEC domains (between 46% and 53%) were described. Domain increases, except Leisure, were maintained 9 months postbaseline (p<0.05).

One study provided mean LEC change scores stratified by dependency level.29 These change scores increased (ie, representing improved QoL) as levels of dependency increased by 11.0 to 13.5 to 17.0 for low, medium and high dependency, respectively, but increases were not statistically significant.

Level of ID and age

One included study stratified ID by age (20–39, 40–59 and 60+) and by level of ID together (mild/moderate and severe/profound).36 As precise numbers in each age category were not provided, results are narratively presented. Following a move to the community at 24 months follow-up, people with mild/moderate ID had non-significant (p>0.05) increases in QoL scores in both the 20–39 and 40–59 age categories, while there were non-significant decreases for those aged 60+. For people with severe/profound ID, there were statistically significant QoL improvements across all age categories (age 20–39, p<0.001; age 40–59 p<0.001, age 60+, p<0.01). Furthermore, participants with severe/profound ID had significantly (p<0.01) lower total QoL scores than those with mild/moderate ID at both baseline and at follow-up. Participants in all age groups and both levels of ID had significantly increased scores across domains, with the exception of non-significant improvement in physical well-being for the youngest mild/moderate ID group and the oldest severe/profound group.

QoL when moving from institutional setting to institutional setting

Two studies evaluated QoL following a move from an institution to either another institution or to a clustered setting (figure 4).31 34 Cluster or campus living refers to specialised housing in an institutional setting or specialised housing for people with disabilities clustered together in an estate/street. This is in contrast to dispersed housing which is non-specialised accommodation spread across a neighbourhood among general population.44 Considerable differences in the type of settings the participants moved to precluded combination in a meta-analysis.

Figure 4.

Quality of life following move from one institution to a different institution.

Overall QoL-Q scores, at both 6 months and 3 years postmove, improved significantly for a sub-group of 19 who moved to refurbished units in a different institution.31 A sub-group of individuals (with challenging behaviour), who moved from institutions to cluster centres (accommodating between 20 and25 residents in each centre) had significantly higher QoL scores at 12 (MD 97.8, 95% CI [68.16 to 127.44]) and 24 months (MD 103.5, 95% CI [75.77 to 131.23]), postmove.34 All QoL sub-domains improved significantly with a linear trend from premove to 12 and 24 months postmove to cluster centres (all p<0.001).34

Direct comparison of two alternative settings demonstrated that individuals who moved from institutions to dispersed small group community homes had significantly higher QoL scores at 12 (MD 26.9, 95% CI [1.27 to 52.53]) and 24 months (MD 39.2, 95% CI [14.31 to 64.09]), postmove compared with clustered settings (figure 5).34 When subdomain outcomes were compared between dispersed community and clustered settings over time, dispersed settings afforded significantly better physical well-being (p<0.005), community access (p=0.001), routines (p<0.01), self-determination (p<0.01), residential well-being (p<0.01) and general life improvements (p<0.001). Groups did not differ on material well-being and social/emotional well-being.

Figure 5.

Quality of life in community versus cluster settings following a move from an institution.

Qualitative studies

The main themes identified in the five qualitative or mixed methods studies were: 1) positive changes experienced following the move to the community and a sense of ‘freedom’ and independence living in the community increased QoL; 2) compatibility among housemates; 3) perceived staff’s role in supporting community living; 4) social integration and family contact; 5) ongoing challenges for individuals’ QoL. Key qualitative findings are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Qualitative data results

| Theme | Qualitative data | Study reference |

| Positive outcome following move to the community | ‘She is happier since the move, more responsive and willing, now that she trusts other people.’ | OâBrien et al, 200139: 75 community staff member. |

| ‘It is a hugely positive, yeah, he has totally changed in his character, in his, the whole, his whole wellbeing has totally changed. He is totally content now’ | Kilroy et al, 201537: 72 people with an intellectual disability’s Key worker. | |

| ‘We actually came down to have a look and I said my God this is like a palace… Oh I loved it, yeah.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538: 271 Tenant 6. | |

| A sense of ‘freedom’ and independence living in the community improved quality of life | ‘My life is better, it’s changed a lot because I have much more freedom…I can get away from others but at the hospital I couldn’t get away… Here I can go out with the staff and I behave myself.’ | OâBrien et al, 200139: 79 people with an intellectual disability. |

| ‘He couldn’t go outside unless he was accompanied. Here, although he needs to be accompanied going out the front door, there is so much space in the back—once the gates are closed he can go on his own. You could see the joy on his face the first day he walked out on his own and he realised that nobody was following him. It was superb.’ | Kilroy et al, 201537: 74 people with an intellectual disability’s Key worker. | |

| Increased personal space and privacy in the community improved quality of life | ‘There is more space to move around in. Life has changed.’ | OâBrien et al, 200139: 79 people with an intellectual disability. |

| ‘It’s big, my room is big… much more room. Yeah, my room was small… terrible in [institutional service setting].’ | Sheerin et al, 201538 Tenant 1. | |

| ‘You have your own space, and then you have your own bedroom, and no one comes into your room without your permission.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538 Tenant 2. | |

| Considering compatibility between housemates critical to quality of life | ‘Once…what we used to have to do was, when he was screaming, we used to have to bring X out of the house, to another (community) house to settle him because he got so traumatised by it. He actually used to go really pale and he’d start sweating and he just wasn’t able to cope with the noise, so we used to have to leave the house without him.’ | Kilroy et al 201537: 72 people with an intellectual disability. |

| ‘I am happy with my life… I’ve got lovely friends. Why I am really happy is that nobody is picking on me or nasty to me. My life has really changed- because I am much more happier and not so stressed out…. I go out more on my own and I’m more independent.’ | OâBrien et al, 200139: 80 people with an intellectual disability. | |

| Perception of staff role in the community | ‘I suppose that there’s probably the same regular staff as well always here now, whereas in the centre it may have changed…so I think that has made a huge improvement too, that he knows exactly…who’s with him and the fact that the staff know him very well, and they know what he will and won’t do, so I think that’s kind of, he kind of trusts people I think.’ | Kilroy et al 201537: 73 people with an intellectual disability’s Key worker. |

| “I think that the staff up there are A1, and then that they’ll do anything for you… but… they might not come near you all night and check on you to see if you’re, you’re okay. One time I was out of work… sick… and then I saw the staff in the morning but in the afternoon no one came near me. I, I didn’t see anyone till about seven, seven or eight o’clock at night… but they stay upstairs in their own bedroom and then they have their own office up there.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538: 276 Tenant 2. | |

| Improved family contact | ‘They… are involved more now that I’m up [here].’ | Sheerin et al 201538: 277 Tenant 5. |

| ‘I wouldn’t have visited her too much in [institutional living setting]… I picked up going back up to visit her on a fairly regular basis.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538: 277 Relative of Tenant 4. | |

| Social integration outcomes | ‘Yeah I do more things… Going to the library… getting to know the people up here in. Sometimes I say hello to them and… They can be friendly yeah, but again if I say hello, certain people might say ‘hello’ and ask you ‘how are you’, you know but other people I think just ignore you.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538 276, Tenant 5. |

| Ongoing challenges | ‘I’m afraid I might fall and there’s nobody there and I might get a pain in my heart.’ | Sheerin et al, 201538: 275 Tenant 6. |

| ‘it’s just that when I get lonely like when the staff go off… I kind of felt a bit lonely today because I was sitting… it can be fairly lonely here… you can’t blame the staff with the cut backs’ | Sheerin et al, 201538: 275 Tenant 6. |

A sense of ‘freedom’ and independence living in the community increased QoL

Positive outcomes for individuals’ well-being following a move to the community were reported in all five studies. In contrast to the experience of living in an institutional setting, individuals’ new living arrangement in the community was perceived as a more suitable environment as it was more private, less noisy with more space including a garden area and wheelchair access.37 38 Increased independence regarding money management gave participants the freedom to make every day personal choices that positively impacted their QoL.38 Compared with their previous experience living in a more restricted residential environment, moving to the community for all participants in three studies was perceived as giving them a sense of ‘freedom’.37–39 Moving to the community was also connected with increased personal space and privacy resulting in improved QoL.

Considering compatibility among housemates increased QoL

More careful consideration of the impact of individuals’ compatibility with housemates when placing individuals in the community houses is reported as positively impacting individuals’ QoL.37 39 In one study, individuals were perceived by proxies to have been previously affected by housemates making noise or engaging in self-injurious behaviour and indicated the importance of housemate compatibility to QoL.37

Perceived staff roles in supporting community living

Staff’s support roles were perceived as contributing to individuals’ QoL.37 38 Permanent staff familiar with individuals’ interests and choices helped improve individuals’ participation in the community and alleviated some individuals’ stress related to staff turnover.37 38 However, some other participants had higher expectations of staff support and involvement, which subsequently negatively impacted their perceived QoL.38

Social integration and family contact

The impact of the move on the individuals’ social integration and family contact as it related to their QoL was a common theme in all five studies. The case study presents the life history of a woman with learning disabilities and severe challenging behaviour who after 30 years in UK institutions, experienced increases in QoL following her eventual move to a small community staffed house.41 In particular, access to individualised day programmes increased perceived positive social integration. Additionally, increased contact with her family due to the community home’s significantly closer proximity to her family meant she ultimately could get to know her siblings after years of separation, and visit her family more regularly. This increased integration into her family’s life had a perceived positive impact on her QoL, as noted especially by her mother.

An Australian mixed methods study specifically focused on the significance of the role of informal social networks on QoL. Four types of informal networks for residents were identified: (1) non-existent (n=4 participants); (2) special occasion family (n=6); (3) engaged family (n=9); (4) friendship-based (n=5). Although one of the community house staff’s key responsibilities was to support residents maintain contact with family and friends following relocation, this was not substantiated in residents’ individual plans.40

In another study, it was perceived that all participants were accessing more services within the community and also ‘getting out into the community’ more as a result of the move.37 However, the individuals with ID were not necessarily more integrated with people in the community, and instead showed a preference for being with people with whom they were more familiar (from the community house). In another study, relatives’ experiences differed on how socially integrated into the community their relatives with ID were, ranging from those who felt their relative was welcomed to others who perceived they were not.38 Overall, most of the participants in this study indicated that they did not feel integrated into the local community and stated that they did not know anyone there. Indeed, some participants appeared to be even more isolated than they were when living in their previous residential setting.

Ongoing challenges for individuals’ QoL

Although all five studies with a qualitative component reported positive outcomes for individuals with ID moving into the community, ongoing challenges to individuals’ QoL were also reported. Adjustment to the move could reportedly take months, depending on the individuals’ transition circumstances. Ongoing difficulties included day programmes being too cramped, with poor consideration of the individuals’ needs in particular in relation to challenging behaviours; unavailability of speech and language therapy or communication aids37; family contact was infrequent and accessing amenities was inconvenient due to a postmove rural location37; lack of adequate funding meant reduced night time community staffing and no overnight trips37; and some participants experienced a loss of security following the move related to change in staffing routines, leading to loneliness and insecurity.38

A summary of the main findings from this review is presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of findings: premove compared with postmove for quality of life in persons with any level of ID and any setting

|

Patient or population: Quality of life Setting: Institutional and Community Intervention:Postmove Comparison: Premove | |||

| Outcomes | No of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Quality of Life: ≤1 year postmove | 246 (5 observational studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate a,b |

|

| Quality of Life: >1 year postmove | 160 (3 observational studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate a,b |

|

GRADE working group grades of evidence.

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated effect.

Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimated effect, but there is a possibility that it is different.

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; ID, intellectual disability.

Discussion

Key findings

Our systematic review yielded quantitative and qualitative findings that deinstitutionalisation is associated with QoL improvements for people with ID. These findings are broadly consistent with prior reviews.23 45–47

There was substantial agreement across quantitative analysis regarding improved QoL which held for shorter (up to 1 year) and longer (more than 1 year) term QoL measures, with a slightly increased difference between premove and longer term QoL (overall) than shorter-term QoL. This challenges to some extent previous findings which indicated modest gains which occurred soon after the move and plateaued at 1 year, with these studies showing continued gains after 1 year.48

When institutional settings close, it tends to happen in a phased approach with evidence showing the younger less complex needs cohort moving first.19 49 The present analysis highlighted the positive gains in QoL that can be experienced by people with severe/profound ID and higher support needs. This finding also held for most aspects or sub-domains of QoL where these were studied.

Qualitative studies found that movement to community residences facilitated an improved sense of well-being, freedom and independent decision-making. When housemate compatibility was more carefully considered prior to their move, individuals had higher quality daily living experiences. There remain, however, challenges for aspects of QoL, including social integration and relationships, and physical well-being for certain subgroups.

Becoming part of the community is considered one of the main advantages associated with living in the community.40 44 In our review, mixed findings are reported on the impact of the move on individuals’ social integration into the wider community. Authentic community participation eluded many individuals and some individuals reported feeling lonelier since the move due to differing expectations of staff supports. This concurs with previous work with regard to the importance of the quality of supports provided and further highlights that an improvement in QoL is not inevitable but must be managed and supported.40 Prior to the move, individuals living in institutional settings had relied more heavily on staff to care for their basic living needs. Following the move to the community with an increased emphasis on nurturing independence, some individuals may experience a loss of security. Without the support from staff to maintain family contact and retain friendships from previous residential setting, individuals’ sense of disconnectedness could be compounded. It would be interesting in future research to see if this disconnect is better bridged over time.

This review indicates that support from staff to facilitate integration into the community while maintaining family and other social contacts is vital to the individuals’ QoL. Individual transition-planning requires thoughtful consideration to address the issue of housemate compatibility, and service user expectations about the level of support provided by staff. Increased contact with family could create new opportunities for family to participate more in supporting social activities (eg, overnight trips and excursions) that could otherwise be restricted due to limited funding. Yet, despite the ostensible QoL benefits of family contact and relationships, and that community living might facilitate same, there is evidence in the findings that social network sizes may not increase significantly in the longer term following a move, and that family contact in fact shows a downwards trend.

Strengths and limitations

This study has followed best practice guidelines in systematic evidence reviews where possible. A search strategy was devised following pilot searches and multiple meetings of a team that includes subject experts in ID, an information specialist and a systematic review specialist. The breadth and thoroughness of the search strategy was illustrated in a very large number (over 25 000) of returned titles and abstracts from databases, and each of these was independently reviewed by two team members. Likewise, all full texts accessed were independently reviewed by two team members. For studies included in the review, quality assessment and data extraction was performed by one reviewer with a corroborating rapid review by a second reviewer. It should be noted that all included studies originated from high-income countries, where deinstitutionalisation has been well established and implemented, and thus generalisability of the findings for low-to-middle-income countries is not clear due to local cultural challenges to implementation. However, the broad findings on enablers to de-institutionalisation in improving QoL, particularly those garnered from the qualitative studies, should provide useful indicators for implementation.

Nevertheless, there are a number of important limitations to our work. We were unable to define ex ante definitions of ‘congregated/institutional’ and ‘community’ settings. In practice, institutions were clearly institutions—places with a number of institutional features, and described as such. Community definitions were more nebulous and we made the best judgements we could as well as providing all available information on the precise conditions in each study, to allow for third party evaluation. We are satisfied retrospectively with this approach. Applying a hard definition would have been very problematic, due to reporting insufficiencies of the extant research. In devising our search strategy we were faced with profound challenges in defining our intervention. While every effort was made to include all potentially relevant terms, as the high number of reviewed titles and abstracts testifies, it is possible that we overlooked some terms that would have captured other relevant material.

Similarly, QoL is a multi-faceted concept with many potential definitions. We considered different approaches to capturing QoL, for example, including all identified sub-domains in the Schalock framework,6 but we did not consider it feasible to identify reliably all named domains and their synonyms. We therefore chose author-defined QoL as our outcome of interest.

In reviewing returned studies from the database search, we used two independent reviewers for title/abstract and full texts, but one reviewer at quality assessment and data extraction with a second reviewer providing a corroborating review. While corroboration by a second reviewer can be acceptable in the review process, the lack of independent second reviewer assessments does introduce the potential for bias in the quality assessment and data extraction phases of the review. Thirty-two (17%) of the studies that we identified as suitable for full text review proved unobtainable and so are not included in our final analyses, thus, potentially introducing selection bias. These studies, however, are on average older than those we were able to access and are listed in online supplementary appendix 5.

The decision to require documentation of consent obtained from participants with ID and ethical considerations did mean that a number of older studies were excluded as well as all of the grey literature. We considered that categorically requiring reporting of a consent process helped to safeguard against: (a) bias derived from inappropriately conducted research (eg, acquiescence), and (b) inclusion of research with inadequate ethical protocols in meta-analyses and consequent publication of new and original research findings based partly on such research. In consideration of the importance of choice and subjective evaluation, and the potential for conflict of interest, we viewed this as an unacceptable risk of bias. However, we are not implying that good or appropriate ethical practice was not adhered to in excluded studies, merely that we could not necessarily ascertain this. The clear majority of research excluded for reasons of ethical considerations also had other methodological shortcomings that would have been sufficient to exclude the study from our review, either in concert with the ethical considerations, or in and of themselves.

Included studies were all observational and had a sample size range of 1 to 76. It is not surprising that observational designs dominate in this field and to maximise confidence in our results we ensured that all included studies met a minimum threshold for methodological quality using the CASP quality assessment tool (that is ‘good/high’ quality). Additionally to assess the level and quality of the evidence for QoL, we performed a GRADE assessment of the summary results. GRADE provides a system for rating the quality of the evidence, based on a collective assessment of study design, risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and magnitude of effect, on the results of meta-analysed data. For both QoL measures, that is up to 1 year postmove, and more than 1 year postmove, the quality of evidence is moderate (downgraded due to observational study designs and statistical heterogeneity) indicating moderate confidence that the average effect estimates are reflective of ‘true’ estimates, and that the addition of further studies is unlikely to substantially change these results (table 5).

Acknowledging the challenges in measurement and reporting of QoL by proxy, particularly for people with severe/profound ID, the analysis used a random effects rather than a fixed effects model, to counterbalance any potential subtle differences across studies with regard level of ID and type of reporting. Future studies could explore the differences in type and change in proxies over time and the impact on QoL measurement. We note the high levels of heterogeneity in the synthesised results for QoL. This, we believe, is likely to be explained by both clinical and methodological variation within the included studies. While we attempted to explore this further through sub-groups analyses, we highlight that it needs to be considered when interpreting the results of the review.

We also included only English language studies in our review, excluding 12 studies on this basis, which is another potential source of bias. These studies are listed in online supplementary appendix 6 and were variously published in French (7), Croatian (2), German (2) and Japanese (1). It was therefore notable that no studies either included in the review or excluded due to language considerations originated in the Nordic countries with the longest history of deinstitutionalisation. It is possible that researchers and/or government agencies in these countries evaluated the impact of deinstitutionalisation prior to the mass uptake of online publishing, and that these evaluations exist somewhere purely offline.

The grey literature search was conducted by topic experts on the websites of research centres active in this field and those of governments in countries at the forefront of deinstitutionalisation in ID. This may have biased reviewed studies against other nations and research groups. While much grey literature was excluded from the review for considerations including lack of comprehensive reporting on ethics, there may be findings of import within that literature that may warrant separate review or discussion.

Future research

Subpopulations with additional needs or who require high-levels of support have received insufficient attention in the literature, and research of high methodological quality is required to better understand the needs of a range of groups. It could be reasonably concluded from the available evidence that a move to the community provides similar benefits for people with more severe levels of ID and that people with high-support needs or challenging behaviour experience similar benefits to their counterparts who have fewer additional needs. This conclusion is based on a few studies and is subject to limitations similar to the wider literature.

With people with ID now living much longer into old age than previous generations, how older age interacts with residential moves also needs comprehensive investigation. Physical well-being has emerged as an aspect of QoL which may not improve as much for groups encompassing younger people with mild ID and older people with severe ID. While it is possible that younger groups reach a relative ceiling of functioning and well-being, with little room for additional improvement per se, older adults with ID may require additional and different supports. Special attention must be paid to the population with dementia, a population which likely faces additional and growing challenges and may require specific supports for optimal QoL. Research is also lacking on people with other specific health needs or impairments (eg, those using ventilators), those who present a forensic risk and ex-prisoners. We have limited information about whether and how these particular groups’ QoL might be affected by where they live, and furthermore how such clients might ultimately be best supported to experience the benefits of community living and optimal QoL.

There is a scarcity of comprehensive data on outcomes more than 2 years postrelocation to the community. Existing evidence indicates that while QoL may increase following a move to a non-institutional setting, it begins to plateau between one and 2 years after the move. Longitudinal studies with longer follow-up periods are warranted to monitor whether the improvement of outcomes is maintained at least in the longer term. Again, serious attention must be paid to the different populations outlined above and to understanding the mechanisms by which changes or improvements in QoL occur, including the impact of changes in services available, proximity to important services and opportunities.

Conclusion

There was a substantial level of agreement between quantitative meta-analytic (ie, SMDs for all movers) and other results, supported by the qualitative findings, that a move to the community was associated with improved QoL compared with the institution. Qualitative studies in particular suggest that observed improvements occur through improved well-being, freedom and independent decision-making, more careful consideration of housemate compatibility, increased family contact and social integration opportunities.

While it is tempting to suggest sufficient evidence exists, there remain a number of unanswered questions. There is not yet enough knowledge about the long-term course of QoL outcomes, which is of particular interest considering the ageing nature of this population, or for specific aspects of QoL, including social integration and relationships. Subpopulations with additional needs or who require high-levels of support have received insufficient attention in the literature, and research of high methodological quality is required to better understand heterogeneity of need and outcome. Moreover, qualitative studies highlighted a number of negative QoL outcomes including insecurity, fear and loneliness that emphasise that gains do not come without a cost. These concerns also need further investigation.

Future research must address these issues to ensure that, as deinstitutionalisation continues around the world in the context of profound demographic change, people with ID are supported to live healthy, independent lives of their own choosing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MMC and PMC co-designed the original review protocol, oversaw all phases of the review process, and drafted and revised the paper. MMC is the guarantor. RLV and EM were lead researchers on all stages of the systematic review (title and abstract, full text, quality assessment, data analysis) and led authorship of the manuscript. PM co-designed the original review protocol, project-managed the review process and, drafted and revised the paper. NW conducted the grey literature search, and drafted and revised the paper. GS was the information specialist, co-designing and running the database searchers, and revising the paper. RS co-designed the original review protocol, advised and contributed throughout the review process as a topic expert, and drafted and revised the paper. VS co-designed the original review protocol, advised and contributed throughout the review process as a systematic review expert, and drafted and revised the paper. CN co-designed the original review protocol, advised and contributed throughout the review process as an economics expert, and drafted and revised the paper. M-AOD co-designed the original review protocol, led the grey literature search, advised and contributed throughout the review process as a topic expert, and drafted and revised the paper.

Funding: The study was funded by the Department of Health (Ireland), with commissioning assistance by the Health Research Board (Ireland).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unpublished data from this study. This is a systematic review that generates no new data. We make our results available in full in the manuscript. Further questions should be directed to the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Nations U. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mansell J, Beadle-Brown J. Deinstitutionalisation and community living: position statement of the comparative policy and practice special interest research group of the international association for the scientific study of intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010;54:104–12. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. May P, Lombard-Vance R, Murphy E, et al. The economic effects of deinstitutionalisation for adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sexton E, O’Donovan M-A, Mulryan N, et al. Whose quality of life? A comparison of measures of self-determination and emotional wellbeing in research with older adults with and without intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2016;41:324–37. 10.3109/13668250.2016.1213377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee McIntyre L, Kraemer BR, Blacher J, et al. Quality of life for young adults with severe intellectual disability: mothers’ thoughts and reflections. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2004;29:131–46. 10.1080/13668250410001709485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schalock RL, Brown I, Brown R, et al. Conceptualization, measurement, and application of quality of life for persons with intellectual disabilities: report of an international panel of experts. Ment Retard 2002;40:457–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schalock RL. The concept of quality of life: what we know and do not know. J Intellect Disabil Res 2004;48:203–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perry J, Felce D. Correlation between subjective and objective measures of outcome in staffed community housing. J Intellect Disabil Res 2005;49:278–87. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Totsika V, Felce D, Kerr M, et al. Behavior problems, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life for older adults with intellectual disability with and without autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:1171–8. 10.1007/s10803-010-0975-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stancliffe RJ. Proxy respondents and the reliability of the quality of life questionnaire empowerment factor. J Intellect Disabil Res 1999;43:185–93. 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simões C, Santos S. The quality of life perceptions of people with intellectual disability and their proxies. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2016;41:311–23. 10.3109/13668250.2016.1197385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stancliffe RJ. Proxy respondents and quality of life. Eval Program Plann 2000;23:89–93. 10.1016/S0149-7189(99)00042-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kane RA. Definition, measurement, and correlates of quality of life in nursing homes: toward a reasonable practice, research, and policy agenda. Gerontologist 2003;43:28–36. 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lesa H, Janet M, Denise P, et al. Assessing family outcomes: psychometric evaluation of the beach center family quality of life scale. Journal of Marriage and Family 2006;68:1069–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katja P, Bea M, Carla V. Domains of quality of life of people with profound multiple disabilities: the perspective of parents and direct support staff. J of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2005;18:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Townsend-White C, Pham AN, Vassos MV. Review: a systematic review of quality of life measures for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours. J Intellect Disabil Res 2012;56:270–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. School of Social Work and Social Policy, La Trobe University. : Bigby C, Fyffe C, Mansell J, From ideology to reality: current issues in implementation of intellectual disability policy. Bundoora, Victoria: Roundtable on intellectual disability policy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCallion P, Jokinen N, Aging JMP, et al. A comprehensive guide to intellectual and developmental disabilities. eds Baltimore: Paul Brookes Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emerson E, Hatton C. Deinstitutionalization in the UK and Ireland: outcomes for service users. J Intellect Dev Disabil 1996;21:17–37. 10.1080/13668259600033021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mansell J. Deinstitutionalisation and community living: progress, problems and priorities. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2006;31:65–76. 10.1080/13668250600686726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Monali C, Bb A. Deinstitutionalization and quality of life of individuals with intellectual disability: a review of the international literature. J of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 2011;8:256–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bigby C, Fyffe C. Tensions between institutional closure and deinstitutionalisation: what can be learned from Victoria’s institutional redevelopment? Disabil Soc 2006;21:567–81. 10.1080/09687590600918032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beadle-Brown J, Mansell J, Kozma A. Deinstitutionalization in intellectual disabilities. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:437–42. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32827b14ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burrell B, Trip H. Reform and community care: has de-institutionalisation delivered for people with intellectual disability? Nurs Inq 2011;18:174–83. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wiesel I, Bigby C. Movement on shifting sands: deinstitutionalisation and people with intellectual disability in Australia, 1974–2014. Urban Policy and Research 2015;33:178–94. 10.1080/08111146.2014.980902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]