Abstract

Purpose

The Trivandrum non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cohort is a population-based study designed to examine the interaction between genetic and lifestyle factors and their association with increased risk of NAFLD within the Indian population.

Participants

Between 2013 and 2016, a total of 2222 participants were recruited to this cohort through multistage cluster sampling across the whole population of Trivandrum—a district within the state of Kerala, South India. Data were collected from all inhabitants of randomly selected households over the age of 25.

Findings to date

Full baseline clinical and pathological data were collected from 2158 participants. This included detailed demographic profiles, anthropometric measures and lifestyle data (food frequency, physical activity and anxiety and depression questionnaires). Biochemical profile and ultrasound assessment of the liver were performed and whole blood aliquots were collected for DNA analysis.

The NAFLD prevalence within this population was 49.8% which is significantly higher than the global pooled prevalence of 25%. This highlights the importance of robust, prospective studies like this to enable collection of longitudinal data on risk factors, disease progression and to facilitate future interventional studies.

Future plans

The complete analysis of data collected from this cohort will give valuable insights into the interaction of the phenotypic and genotypic profiles that result in such a dramatic increased risk of NAFLD within the Indian population. The cohort will also form the basis of future lifestyle interventional studies, aimed at improving liver and metabolic health.

Keywords: hepatology, epidemiology, hepatobiliary disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This large population-based cohort is designed to examine the interaction between the genetic and lifestyle factors which contribute to increased non-alcoholic fatty liver disease risk in India.

Though limited to the district of Trivandrum, population-level sampling to include participants from both urban and rural domiciles makes it one of the largest cohort studies of its kind.

Extensive baseline data include detailed cohort phenotyping (including food frequency and physical activity data) as well as biochemical profiles and whole blood aliquots for DNA analysis.

Low rates of migration and robust cohort infrastructure will enable comprehensive longitudinal follow-up and form the basis for future interventional studies.

Introduction

Rising levels of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and the metabolic syndrome (MetS) are a global health concern. The risk of T2DM is increasing worldwide, particularly in Indian populations where the risk is higher in both native and migrant populations compared with other ethnicities,1 and at a lower body mass index (BMI).2

One of the consequences of this metabolic pandemic is increasing prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) which is thought to be the hepatic manifestation of MetS. NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of disease from simple steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, through increasing stages of fibrosis to cirrhosis—which may result in liver decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma and death. Individuals with NAFLD, particularly those with MetS, have higher overall mortality, cardiovascular mortality and liver-related mortality compared with the general population.3 NAFLD is particularly prevalent in Western populations,4 but with the westernisation of Asia-Pacific culture, we are seeing increasing levels of obesity, MetS and NAFLD in this group.5 The rise in MetS and its complications is variable according to region and degree of urbanisation—being induced by a variety of lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise habits.6

A recent meta-analysis showed that the pooled global prevalence of NAFLD is 25%.7 The issue with this generalisation is that it is mainly based on large studies from the USA, which include small numbers of people of Indian ethnicity. The documented prevalence of NAFLD also varies depending on the diagnostic tool used. In low/middle-income countries (like India) it is difficult to perform large population-based studies, with those that are published being biased towards urban, tertiary centres where ultrasound and biopsy are more readily available.8 Evidence has shown that within these urban areas—often of higher socioeconomic class—there are higher rates of NAFLD and as such these studies are likely to give an overestimate of NAFLD prevalence in India.9

The creation of the Trivandrum NAFLD cohort was funded and supported by the NIHR Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Unit, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University Of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, with data collection and management run through the Population Health and Research Institute (PHRI), Trivandrum, Kerala, India. PHRI has specific expertise in population-based studies, having established and run the Trivandrum Tobacco Study (a study of tobacco habits of 0.4 million men in Trivandrum), which has undergone five yearly follow-ups since 2002 (data can be found through https://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/research/the-trivandrum-tobacco-study). The Trivandrum NAFLD cohort was created to examine how the interaction between genetics and lifestyle factors results in increased risk of NAFLD within this population. The cohort will combat the paucity of population-based studies in India and enable accurate estimation of NAFLD prevalence within an Indian population as a whole (including both urban and rural domiciles). It will also allow the development of a nested case–control study to look at the impact of different variables on NAFLD risk. Through large, population-based sampling of a relatively static populace, this cohort will also facilitate further disease-specific studies (including interventional studies), genetic studies, and has the capability of generating longitudinal follow-up data.

Cohort description

Cohort creation

Trivandrum (Thiruvananthapuram) is the southernmost district in the state of Kerala, located on the south-western coast of India (figure 1). At the time of the Indian census in 2011, it had a population of 3.3 million divided into urban and rural domiciles (urban 54%, rural 46%—census data captured through https://www.census2011.co.in/). The Trivandrum NAFLD cohort was created between February 2013 and July 2016 through population-based sampling of all inhabitants over the age of 25 years.

Figure 1.

Map of Kerala.

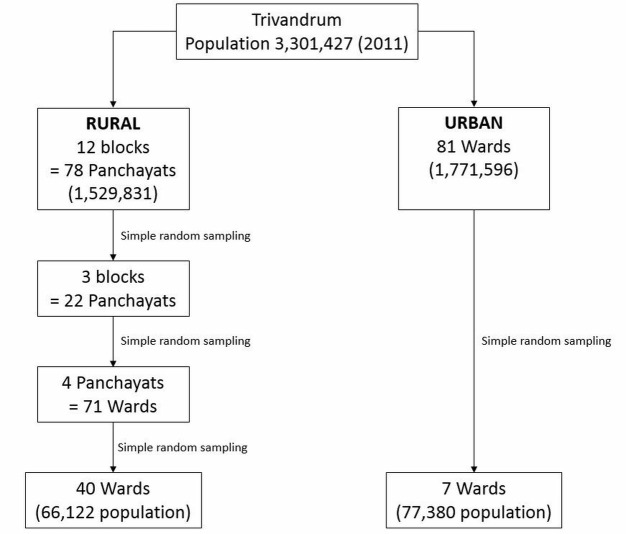

As described, Trivandrum has both urban and rural districts. As per the population census, the rural districts are divided into 12 blocks, which are themselves formed of 78 panchayats (originally denoting a village council). Panchayats are then subdivided further into wards (originally denoting a local authority area—usually indicating a neighbourhood). The urban districts are divided into wards only.

The enrolment of study participants was done through unweighted multistage cluster sampling. Using random number tables, 3 of 12 rural blocks were selected (made up of 22 panchayats), 4 rural panchayats were selected out of 22 (made up of 71 wards) and, finally, 40 of 71 wards were selected. Using the same technique, 7 of 81 urban wards were selected (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trivandrum non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cohort sampling framework.

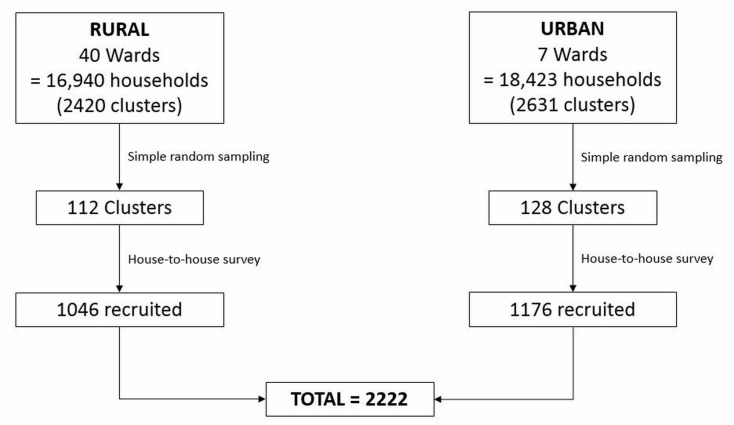

Using the Trivandrum electoral roll from 2011, households within these wards were grouped into clusters of seven. Using random number table, 112 of 2420 rural clusters and 128 of 2631 urban clusters were identified for sampling. Each household within the chosen clusters was sampled, and through house-to-house survey by local social workers all eligible inhabitants were invited to enrol. For some households this meant repeated visits to ensure all those who were eligible (anyone over the age of 25 years) were given the opportunity to participate. At the time of recruitment, within the household, baseline demographic, anthropometric and medical history data were collected.

Originally the aim was to recruit around 2000 cases of NAFLD. Based on an estimated NAFLD prevalence of 31.8% from a previous pilot study,10 this would mean recruiting a total cohort of 10 000 participants. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, cohort recruitment at household level was ceased at around 2000 participants (figure 3), which based on estimated prevalence would result in 840 NAFLD cases.

Figure 3.

Trivandrum non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cohort recruitment diagram.

In order to collect pathological data (including bloods and abdominal ultrasound), study camps were held within the area local to the selected wards and those who had been recruited were invited to attend. Of the original 2222 population sample, 2161 participants attended the camps—demonstrating a high attendance rate with only 3% dropout. Three participants did not have an ultrasound so were excluded, leaving the total number of participants as 2158. Analysis of the demographic/anthropometric data of those who did and did not have an ultrasound shows that a higher proportion of men (61% vs 40.6%, p<0.001) and a higher proportion of people within the rural setting (73.4% vs 46.3%, p<0.001) did not attend. This is likely due to the difficulty in getting to the rural camps (which covered a larger geographical area than the urban camps), and that men were often limited by their need to work.

Data collection

Clinical data were collected through house-to-house survey and pathological data were collected through the local study camps. This is outlined below.

Clinical data

Potential participants were approached and consented to the cohort through house-to-house survey by social workers within their wards. Initial clinical data were collected at the time of consent within the participant’s home. Baseline demographic data included date of birth, gender, level of education, work status, marital status and religion. Information on medical history was also documented along with history of tobacco smoking/chewing and alcohol intake. Anthropometric data collected during household visits included height measured in centimetres using a wall-mounted vertical rule, weight measured in kilograms using mechanical standing scales, waist circumference—taking an average of two measurements in centimetres using a non-expandable tape between the lower rib margin and iliac crest, and an average of three blood pressure readings in mm Hg taken using a manual cuff in a sitting position. Participants undertook a regional Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), designed to incorporate variation in nutrient intake attributed to local recipes according to domicile, social class and religion. The validation of this FFQ is ongoing—using repeated 24 hours’ food diaries and blood/urine biomarkers. Participants also undertook the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire11 and Duke Anxiety-Depression Scale (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).12

Pathological data

Participants who attended the study camps had blood taken for assessment of liver function, platelet count, fasting glucose, insulin and lipids. Additional whole blood aliquots were taken for DNA extraction. Participants then underwent abdominal ultrasonography to assess presence and grade of fatty infiltration (Grade 1: liver echogenicity is increased. Grade 2: echogenic liver obscures the echogenic walls of portal vein braches. Grade 3: echogenic liver obscures the diaphragmatic outline).13 Those who had evidence of NAFLD subsequently underwent transient elastography (FibroScan) as a surrogate marker to stage degree of fibrosis (≥8 kPa indicating presence of significant fibrosis).

Statistical analyses

Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentage) and continuous data as mean (SD) for normally distributed data and medians (range) for non-parametric data. Univariate analysis to compare characteristics of the cohort with/without NAFLD was undertaken using Student’s t-test (normal continuous), Mann-Whitney U test (non-normal continuous) and Χ2 test (categorical).

Baseline characteristics

Demographic data from the population sample (n=2222) and NAFLD cohort (n=2158) compared with the census data of Trivandrum in 2011 are outlined in table 1. The NAFLD cohort has a larger proportion of women to men and a larger proportion of Hindu population than the national average. Importantly, the proportion of rural and urban population within the cohort matches the census, implying adequate population-level sampling.

Table 1.

Comparison of the population sample demographics to the Trivandrum population census and comparison of the NAFLD cohort demographics to the population sample

| Demography | Census (n=3 301 427) |

Population sample (n=2222) |

p value | NAFLD cohort (n=2158) |

p value |

| Gender | |||||

| Male, n (%) | 1 581 678 (47.9) | 915 (41.2) | * | 876 (40.6) | * |

| Female, n (%) | 1 719 749 (52.1) | 1307 (58.8) | 1282 (59.4) | ||

| Domicile | |||||

| Rural, n (%) | 1 529 831 (46.3) | 1046 (47.1) | p=0.49 | 999 (46.3) | p=1.04 |

| Urban, n (%) | 1 771 596 (53.7) | 1176 (52.9) | 1159 (53.7) | ||

| Literacy (%) | 93.0 | 98.0 | p=0.09 | 98.0 | p=0.09 |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu, n (%) | 2 194 057 (66.5) | 1821 (81.9) | * | 1765 (81.8) | * |

| Muslim, n (%) | 452915 (13.7) | 170 (7.7) | * | 167 (7.7) | * |

| Christian, n (%) | 630573 (19.1) | 231 (10.4) | * | 226 (10.5) | * |

| Other, n (%) | 23882 (1) | 0 | 0 |

*p<0.001.

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Findings to date

A total of 2158 participants were included in the final cohort. The prevalence of NAFLD within this population-based cohort is 49.8% (n=1075).

Within this cohort, a nested NAFLD case–control study has been done to look at the difference in aetiological factors between those with NAFLD and those without. In order to do this, data from the original NAFLD cohort (2158) were cleaned to remove other causes of non-NAFLD-related liver disease such as alcohol intake >21 units per week and alternate causes of an echo-bright liver (such as history of viral hepatitis or other liver disease), leaving a subcohort of 2089 (NAFLD 49.8%). Baseline demographic data from this subcohort are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Nested NAFLD case–control demographics. Diabetes defined as formal diagnosis, treatment or fasting glucose >126 mg/dL

| Demography | NAFLD n=1040 | Control n=1049 | p value |

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.34 (10.74) | 45.98 (12.31) | * |

| Gender | |||

| Male, n (%) | 473 (45.5) | 339 (32.3) | * |

| Female, n (%) | 567 (54.5) | 710 (67.7) | |

| Domicile | |||

| Rural, n (%) | 417 (40.1) | 543 (51.8) | * |

| Urban, n (%) | 623 (59.9) | 506 (48.2) | |

| Literacy, n (%) | 1018 (97.9) | 1027 (97.9) | 0.978 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.90 (4.16) | 24.30 (4.08) | * |

| Underweight, n (%) <18.5 kg/m2 | 4 (0.4) | 68 (6.5) | |

| Normal weight, n (%) 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 | 165 (15.9) | 336 (32) | |

| Overweight, n (%) 23–24.9 kg/m2 | 195 (18.8) | 222 (21.2) | |

| Obese, n (%) >25 kg/m2 | 675 (64.9) | 423 (40.3) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 355 (34.13) | 195 (18.59) | * |

| HOMA-IR, median (IQR) | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.07 (0.07) | * |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 417 (40.1) | 240 (22.88) | * |

| Cholesterol, mean (SD) | 219.19 (44.05) | 212.26 (44.34) | * |

| HDL, mean (SD) | 47.65 (11.25) | 50.35 (11.83) | * |

| Triglycerides, median (IQR) | 133 (85) | 94.5 (59) | * |

| LDL-C, mean (SD) | 140.71 (39.04) | 140.03 (38.87) | 0.689 |

HOMA-IR ((fasting insulin*fasting glucose)/405) calculated for those not on treatment for diabetes. LDL-C=(total cholesterol−HDL cholesterol−(triglycerides/5)).

*p<0.001.

BMI, body mass index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Overall, females outnumbered males and constituted 1277 of the total 2089 participants. 55.2% of the urban population had NAFLD compared with 43.4% of the rural population (an unadjusted OR of 1.60, 1.35–1.91)—a finding which is consistent with the literature on increased NAFLD prevalence in areas of higher socioeconomic class.14 As expected, mean BMI was higher in the NAFLD group (OR 1.79 if overweight, OR 3.25 if obese) as was rate of diabetes (OR 2.27, 1.85–2.79) and MetS (OR 2.26, 1.86–2.74). These data are presented in table 3. Under logistic regression, for every unit increase in BMI, the odds of having NAFLD increases by 1.17 (17%) (1.15–1.20, p<0.001).

Table 3.

NAFLD ORs adjusting for sex, domicile, BMI category (with normal weight as baseline), diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Variables were mutually adjusted for each other with baseline categories being those variables presented

| Variable | Unadjusted OR (95% CI, p value) | Adjusted OR (95% CI, p value) |

| Male sex | 1.75 (1.46 to 2.09, p<0.001) | 2.22 (1.82 to 2.72, p<0.001) |

| Urban domicile | 1.60 (1.35 to 1.91, p<0.001) | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.46, p=0.048) |

| BMI | ||

| Underweight <18.5 kg/m2 | 0.12 (0.04 to 0.34, p<0.001) | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.41, p<0.001) |

| Overweight 23–24.9 kg/m2 | 1.79 (1.36 to 2.34, p<0.001) | 1.78 (1.34 to 2.35, p<0.001) |

| Obese >25 kg/m2 | 3.25 (2.58 to 4.10, p<0.001) | 3.27 (2.57 to 4.16, p<0.001) |

| Diabetes | 2.27 (1.85 to 2.79, p<0.001) | 1.63 (1.28 to 2.07, p<0.001) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 2.26 (1.86 to 2.74, p<0.001) | 1.62 (1.29 to 2.07, p<0.001) |

BMI, body mass index; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

These data confirm commonality of NAFLD risk factors between India and the Western world. Increasing levels of obesity and the dramatic rise in diabetes prevalence in India1 is reflected in the WHO Global Burden of Disease study, which shows that hypertension and raised fasting blood glucose are the leading cause of non-communicable disease in India, unlike other low/middle-income countries where childhood malnutrition and unsafe water predominate.15 This is reflected within this cohort, where we demonstrate high rates of diabetes—well above the 2011 estimated population prevalence of 8.3%1—even within the control group. The main reason for this is the fact that the inception cohort from which the case and control groups were identified included only people of 25 years of age and older, enriching the cohort with people with an age group where prevalence of type 2 diabetes is expected to be substantially higher. In addition, collection of fasting blood glucose levels at enrolment enabled us to identify those who meet the International Diabetes Federation criteria for diabetes without previous diagnosis.

Interestingly, presence of obesity conveys the strongest risk of NAFLD within this group (above diabetes) which highlights the ‘Asian paradox’—where cardiovascular risk increases with BMI in Asians, as in other ethnicities, but at a lower BMI. These data support the significant impact of BMI on risk of disease in this group and the reclassification of BMI cut-offs that was implemented in 2000.2

Recruitment to the Trivandrum NAFLD cohort was completed in July 2016. As yet, it has not undergone a complete follow-up. The aim of the project is to collect longitudinal data on risk factors for NAFLD progression and to make an assessment of long-term outcomes such as incident diabetes, cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality rates using verbal autopsy—a validated instrument used to ascertain time and cause of death.16 Further lifestyle data that were collected from the cohort were under review with the aim to look at the impact of diet and physical activity on risk of NAFLD, both in native Indians and on those who now live in the UK. Data on liver stiffness within the NAFLD subgroup will be combined with a larger piece of work looking at the identification and stratification of liver disease in Trivandrum as a whole.

The cohort also forms the basis of a Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) recently awarded to the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) in collaboration with PHRI to develop lifestyle interventions for improved liver and metabolic health in South India. As a part of GCRF, a pilot randomised controlled trial of 16 months’ dietary intervention with low glycaemic index food with yoga sessions versus yoga sessions alone has been initiated in the NAFLD cohort developed and described here (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03844165).

Finally, DNA has been extracted from whole blood aliquots from this cohort with the aim to complete the first genome-wide association study of NAFLD within an Indian population.

Strengths and limitations

The biggest strength of the Trivandrum NAFLD cohort is the fact that it was designed to collect detailed anthropometric, clinical and pathological data at a population level, representing the full spectrum of demography of a large Indian state. Through population-level sampling we have enabled accurate estimation of NALFD prevalence, which given its significant departure from the estimated global prevalence has filled an important gap in the knowledge base. NAFLD prevalence of 31.8% was estimated from a previous pilot study,10 which was reliant on raised liver enzymes to identify patients for further investigations, hence, underestimated the true prevalence in this population. Through the utilisation of local social workers within the community, PHRI has created a cohort with excellent uptake and retention of participants, has methods in place to document rates of migration and accurate mortality data as well as having the infrastructure and manpower in place to facilitate longitudinal and interventional studies.

The main limitation of the study from a clinical perspective is the use of ultrasound as the diagnostic tool for NAFLD. Ultrasound has been shown to have a poor yield in the diagnosis of microvesicular fat within the liver, with an overall sensitivity of 43% and specificity of 73%.17 This means that our NAFLD prevalence of 49.8% may in fact be an underestimate. Liver biopsy is generally considered to be the gold standard for NAFLD diagnosis, but its invasive nature combined with its inherent risk of sampling error makes it unsuitable for population-based studies. Despite this, the message that NAFLD prevalence is significantly higher in this Indian population compared with the global estimates is an important one. Finally, although representative of a large Indian population, the data collected from this cohort are not necessarily representative of the India as a whole—whose diverse population includes thousands of distinct and unique cultures.

Patient involvement

Participants of the Trivandrum NFALD cohort were not involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures of this project, but during data collection the patient and public involvement team from the NIHR Nottingham BRC ran a 3-day workshop alongside PHRI in Trivandrum. During this workshop, participants were consulted on their opinions of having lifestyle information collected, and the best way to do this. This qualitative feedback has helped shape the way we approach data collection from a cultural standpoint in this ethnic group.

Footnotes

Contributors: KTS and GPA contributed the original concept and design of the study. KTS, KBL and JLG were involved in data collection and sample management. JC and LB did the data analysis and interpretation while JC, LB and KLE drafted the work. All the authors have critically revised this article and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: The Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre (Digestive Diseases theme) supports PHRI and is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

Disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Sree Gokulam Medical College and Research Foundation, Venjaramoodu, Trivandrum, India.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Researchers may request access to data and biomaterial by contacting the corresponding author.

Collaborators: Both the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre (Gastrointestinal and Liver Disorder theme) and Population Health and Research Institute (PHRI) welcome interest and collaboration with national and international colleagues. For further information please contact the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;94:311–21. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong JP, Pitts A, Younossi ZM. Increased overall mortality and liver-related mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2008;49:608–12. 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S99-s112. 10.1002/hep.20973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohan V, Farooq S, Deepa M, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in urban south Indians in relation to different grades of glucose intolerance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;84:84–91. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohan V, Shanthirani S, Deepa R, et al. Intra-urban differences in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in southern India–the Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS No. 4). Diabet Med 2001;18:280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84. 10.1002/hep.28431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prashanth M, Ganesh HK, Vima MV, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India 2009;57:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh S, Kuftinec GN, Sarkar S. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in South Asians: A Review of the Literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2017;5:1–6. 10.14218/JCTH.2016.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. K T S. Prevalence and risk factors for non-alcoholic fatty liver in a transition society with high incidence of diabetes mellitus. in The 15th Annual Conference of the INASAL. Vellore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cleland CL, Hunter RF, Kee F, et al. Validity of the global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ) in assessing levels and change in moderate-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1255 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parkerson GR, Broadhead WE. Screening for anxiety and depression in primary care with the Duke Anxiety-Depression Scale. Fam Med 1997;29:177–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saadeh S, Younossi ZM, Remer EM, et al. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:745–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen KF, Dufour S, Feng J, et al. Increased prevalence of insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asian-Indian men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:18273–7. 10.1073/pnas.0608537103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jha P, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, et al. Prospective study of one million deaths in India: rationale, design, and validation results. PLoS Med 2006;3:e18 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Khiyami A, et al. Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 2009;51:1061–7. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]