Abstract

Ciliocytophthoria (CCP) defines a degenerative process of the ciliated cells consequent to viral infections, and it is characterized by typical morphological changes. We evaluated the distinct and characteristic phases of CCP, by means of the optical microscopy of the nasal mucosa (nasal cytology), in 20 patients (12 males and 8 females; aged between 18 and 40 years). Three phases of CCP by nasal cytology are detected. This outcome confirms that CCP represents a sign of suffering nasal epithelial cell. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: virosis, ciliocytophthoria, nasal cytology, rhinitis

It is well known that the term ciliocytophthoria defines a degenerative process of the ciliated cells consequent to viral infections, and it is characterized by typical morphological changes. Joseph Leidy firstly described asmathosis ciliaris in samples recovered from asthmatic patients: i.e. damaged respiratory cells (1). Later, Hilding reported aberrant nasal cells similar to parasitic cells (2). Papanicolau coined the term ciliocytophthoria (CCP) to identify the degenerative process in the bronchial ciliated cells observed during virosis and bronchial carcinoma (3). After that, other terms (pseudoprotozoa and “pseudomicrobe”) were used rather than CCP. It confirms the confusion between degenerative process of ciliated cells and flagellated protozoa frequently found in airways (4-7). Further, electron microscopy exactly characterized CCP and allowd to correctly include it into the degenerative phenomena during respiratory infections (8, 9).

Experimental CCP has been reproduced in an animal model, exposing porcine and equine respiratory epithelium to a wide variety of pathogens (10, 11). In human studies, CCP is observed during acute tonsillitis and viral infections (12, 13), as well as in vaginal smear and peritoneal lavages (3, 14-17). Most of studies report CCP as characterized by “cellular fragments”, without nuclei, with a regular rhythmic movement of the cilia at one edge and a well distinguishable “terminal bar”.

On the basis of this background, we evaluated the distinct and characteristic phases of CCP, by means of the optical microscopy of the nasal mucosa (nasal cytology), in 20 patients (12 males and 8 females; aged between 18 and 40 years), who attended the outpatient Center of Rhinology of the University Hospital of Bari (Italy). All patients were affected by viral infections of the upper airways. All patients signed an informed consent and the procedure was approved by the Review Board. Serological data confirmed virous infection (i.e. Influenza virus type A). All patients had nasal congestion, sneezes, watery rhinorrhea, cough, fever, headache, and chills. Anterior rhinoscopy showed hyperemia of the inferior turbinate and clear and abundant mucous. Oropharyngoscopy showed hyperemia of the tonsillar pillars and the oropharyngeal posterior wall. All patients underwent nasal cytology (20, 21).

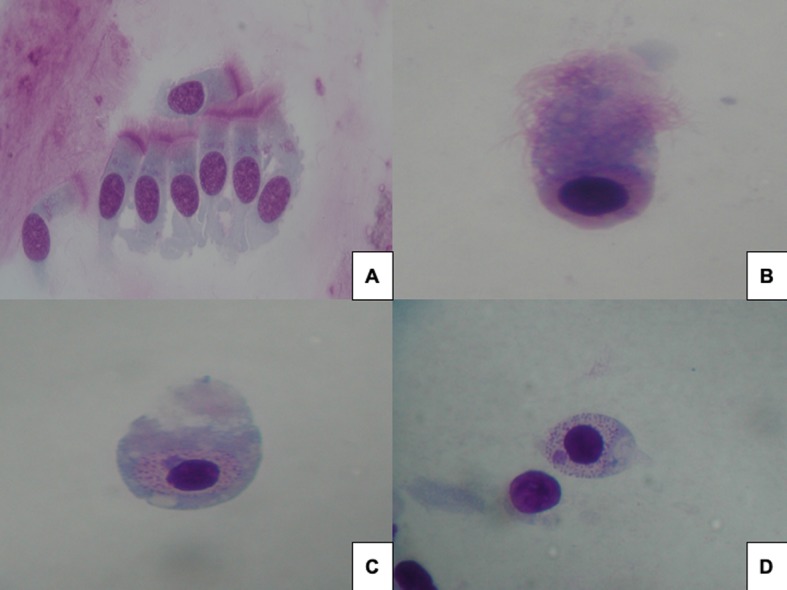

All patients had pathological rhinocytograms, characterized by cytopathic alterations consequent to viral infections, including numerous neutrophils and lymphocytes, some columnar cells, part of the ciliated cells, with various degrees of CPP. Figure 1a shows that the typical normal ciliated cell is visible, with its well-conformed ciliary apparatus, with a homogeneous cytoplasm, a finely represented chromatin in the nucleus, an easily recognizable nucleolus and the characteristic supranuclear hyperchromatic stria (SHS +). Notably, at least three distinct phases of CCP are distinguishable during viral infection. The first phase (Figure 1b) is characterized by an initial rarefaction of the ciliary apparatus, with disappearance of the SIS, early cytoplasmic vacuolization and internal reorganization of the chromatin (heterochromatin) forming little clumps. The second phase (Figure 1c) consists of further rarefaction of the ciliary apparatus, leading to its disappearance and confluence of the intracytoplasmic vacuoles; in the nucleus, chromatin tends to coalescence and to compact, with a peripheral halo where the nucleolus is clearly visible. The third phase (Figure 1d) is characterized by the “decapitation” of the apical portion of the ciliated cell, secondary to the latero-lateral confluence of the cytoplasmic vacuoles, so only the caudal portion of the cell (represented by the nucleus and its nucleolus, surrounded by a thin cytoplasm remnants) is visible.

Figure 1.

a) normal ciliated cell with hyperchromatic stria; b) initial rarefaction of cilia and disappearance of the stria; c) further rarefaction with disappearance of intracytoplasmic vacuoles; d) decapitation of apical part of ciliated cell

Acute upper airways inflammation is usually caused by viruses, even though after the viral infection a bacterial overlapped infection may occur, partly favored by the cytopathic effect of the virus itself on the mucosa. Ciliated cells are the most differentiated cells of the nasal mucosa and therefore they are more prone to attack by infections. The most common viruses are Rhinovirus, Myxovirus (Influenza virus), Paramyxovirus (Parainfluenza virus), Coronavirus, Adenovirus and Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).

CCP has a relevant diagnostic importance. However, a clear description of the cytomorphologic phases of this phenomenon are not depicted in the currently available literature. Nowadays, nasal cytology, a branch of Rhinology, allows to detect and define the different phases of CCP. The current findings are consistent with previous reports (22), except for the presence of the perinuclear halo, surrounding the nuclear chromatin, is just that portion of the nucleus where the chromatin is absent. The condensation of the hyperchromatic nuclear content could be responsible for formation of the rarefied “intranuclear halo” where the nucleolus is visible.

Of course, further studies of electron microscopy focused on CCP are needed to confirm our preliminary impressions.

In conclusion, the current study precisely describes the three phases of CCP by nasal cytology and confirms that CCP represents a sign of suffering nasal epithelial cell.

Conflict of interest:

None to declare

References

- 1.Wier A, Margulis L. The wonderful lives of Joseph Leidy (1823-1891) Int Microbiol. 2000;3:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilding AC. The common cold. Arch Otolaryngol. 1930;12:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papanicolaou GN. Degenerative changes in ciliatedd cells exfoliating from the bronchial epithelium as a cytologic criterion in the diagnosis of diseases of the lung. NY State J Med. 1956;56:2647–2650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce CH, Knox AW. Ciliocytophthoria in sputum from patients with adenovirus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960;104:492–495. doi: 10.3181/00379727-104-25886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblatt MB, Trinidad S, Lisa JR, Tchertkoff V. Specific epithelial degeneration (Ciliocytophthoria) in inflammatory and malignant respiratory disease. Chest. 1963;43:605–612. doi: 10.1378/chest.43.6.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadziyannis E, Yen-Lieberman B, Hall G, Procop GW. Ciliocytophthoria in clinical virology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1220–1223. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1220-CICV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutisova K, Kulda J, Cepicka I, et al. Tetratrichomonads from the oral and respiratory tract of humans. Parasitology. 2005;131:309–319. doi: 10.1017/s0031182005008000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy GF, Brody AR, Craighead JE. Exfoliation of respiratory epithelium in hamster tracheal organ cultures infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;389:93–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00428670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez-Giron R, Doganci L, Ribas A. From the 19th century to the 21st, an old dilemma: ciliocytophthoria, multiflagellated protozoa, or both? Diagn Cytopathol. 2008 Aug;36(8):609–11. doi: 10.1002/dc.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams PP, Gallagher JE, Pirtle EC. Effects of microbial isolates on porcine tracheal and bronchial explant cultures as observed by scanning electron microscopy. Scan Electron Microsc. 1981;4:141–150. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950040304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman KP, Roszel JF, Slusher SH. Inclusions in equine cytologic specimens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki Y, Abe H, Tokunaga E, Tsuzuki T, Fujioka T. Ciliocytophthoria (CCP) in nasopharyngeal smear from patients with acute tonsillitis. Acta Oto. 1988;454(suppl):175–177. doi: 10.3109/00016488809125022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasaki Y, Korematsu M, Naganuma M. Ciliocytophthoria (CCP) in nasal secretions: relation of viral infection to otorhinological disease [in Japanese] Josai Shika Daigaku Kiyo. 1987;16:441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahoney CA, Sherwood N, Yap EH, Singleton TP, Whitney DJ, Cornbleet PJ. Ciliated cell remnants in peritoneal dialysis fluid. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clocuh YP. Ciliocytophthoria in pulmonary and vaginal cytology [in German] Medizinische Welt. 1978;29:1044–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clocuh YP. Ciliocytophthoria in the cervical smear [in German] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1978;38:229–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubel E, Kanitz M, Kuhlmann U. Ciliocytophthoria in peritoneal dialysis effluent. Perit Dial Int. 1990;10:179–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidaway MK, Poonam C, Oertel YC. Detached ciliary tufts in female peritoneal washings: a common finding. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:841–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadziyannis E, Yen-Lieberman B, Hall G, Procop GW. Ciliocytophthoria in clinical virology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000 Aug;124(8):1220–3. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1220-CICV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelardi M, Fiorella ML, Russo C, Fiorella R, Ciprandi G. Role of nasal cytology. Int J Immunopathol Pharm. 2010;23:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelardi M. 2nd ed. Milan, Italy: Edi Ermes; 2012. Atlas of nasal cytology. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelardi M, Cassano P, Cassano M, Fiorella ML. Nasal cytology: description of a hyperchromatic supranuclear stria as a possible marker for the anatomical and functional integrity of the ciliated cell. Am J Rhinol. 2003 Sep-Oct;17(5):263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]