Abstract

Background:Unilateral twin tubal pregnancy is an extremely rare condition, occurring in 1/20.000-250.000 pregnancies and represents a major health risk for reproductive-aged women, leading to even life-threatening complications. Aim:We present a case of a 31-year-old woman with unilateral twin tubal pregnancy, treated with methotrexate and then surgically because of failure, followed by review of the literature. Methods: Researches for relevant data were conducted utilizing multiple databases, including PubMed and Ovid. Results: The most common type of twin ectopic pregnancy is the heterotopic (1/7000 pregnancies) in which in which both ectopic and intrauterine pregnancy occur simultaneously. Expectant, medical and surgical therapy have similar success rates in correctly selected patients. Two prospective randomized trials did not identify any statistically significant differences between groups receiving MTX as a single dose or in multiple doses. Among the 106 cases reported in literature, methotrexate was tried just in 4 patients (3 unilateral and 1 bilateral) before ours. Details are reported in the table 1. Conclusion: The recent shift in the treatment of singleton ectopic pregnancies to the less invasive medical therapy might apply even in the case of twin implants. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: unilateral, twin tubal pregnancy, rare condition

Case presentation

Our 31-year-old patient (gravida 2, para 0) had a history of endometriosis and right tubal pregnancy treated with laparoscopic salpingectomy 7 months earlier at our institution.

On a routine ultrasound, at an estimated gestational age of 6 weeks and 2 days given her last menstrual period, a left ectopic pregnancy was suspected so she was sent to our emergency room. Vitals were all stable and the patient was well, conscious and well-oriented.

On physical examination her abdomen wasn’t tender and just slight left adnexal tenderness was elicited. Vaginal bleeding was light.

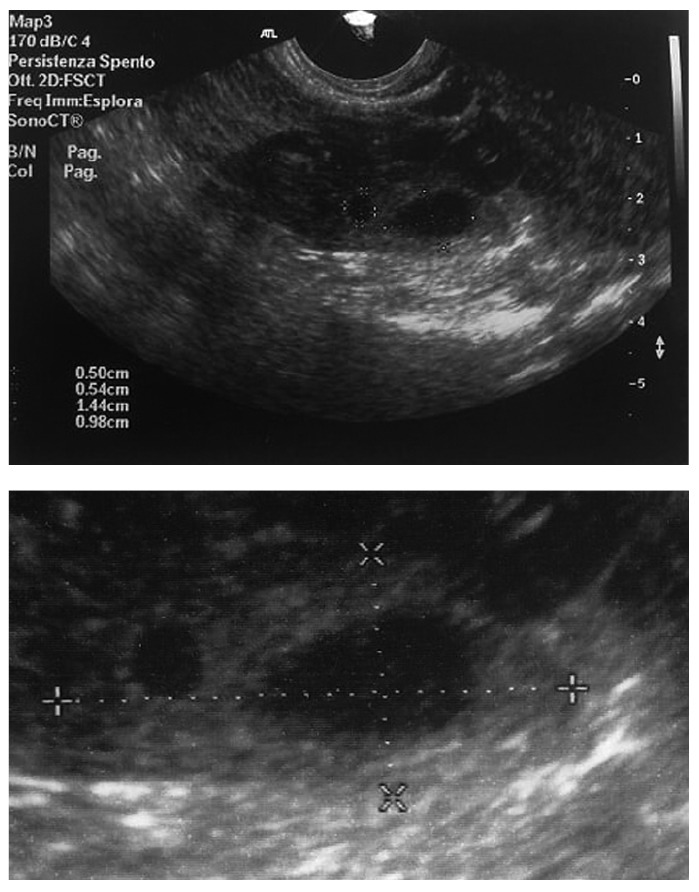

Ultrasound revealed an empty uterine cavity and in the left adnexa, adjacent to the ovary, a complex mass measuring 29 × 16 mm encompassing to a further evaluation 2 thick-walled fluid-filled cystic masses measuring 5 and 16 mm (Fig. 1). No fluid in the pouch of Douglas was identified. Serum βhCG level was 13217 mIU/ml. The patient was then diagnosed with unilateral twin tubal pregnancy. As she was stable without any sign of tubal rupture and considering as well the previous right salpingectomy, we administered a single dose of methotrexate (50 mg/m2, corresponding to 75 mg) + folinic acid rescue (5 mg once a day by mouth). 4 days later βhCG level was 23276 mIU/ml (+76%) and 7 days later 19783 mIU/ml (-15%). Ultrasound monitoring revealed no change. Patient was asymptomatic. A second dose of MTX (still 50 mg/mq) + folinic acid rescue was then administered.

Figure 1.

7 days after the second MTX dose βhCG level was 16000 mIU/ml (-19%), ultrasound was unchanged and the patient asymptomatic. A third dose of MTX (still 50 mg/mq) + folinic acid rescue was administered.

4 days after the last dose, the patient came to our emergency room complaining pelvic and abdominal mass. βhCG level was 3659 mIU/ml (-77%), ultrasound revealed increasing mass dimensions as 41 × 27 mm and estimated 100 ml of blood in the pouch of Douglas.

Laparoscopic left salpingectomy was performed, total blood loss was 2500 ml and the patient underwent intraoperatively a blood transfusion. The pathology specimen confirmed the twin tubal pregnancy. The post-operative course was regular. The patient was well on 6-months follow up.

Review and comparison

Methodology

Researches for relevant data were conducted utilizing multiple databases, including PubMed and Ovid. Searches included combinations of the key terms: ‘twin and ectopic pregnancy’, ‘twin and tubal pregnancy’, ‘twin heterotopic pregnancy’, ‘laparoscopy and twin pregnancy’, ‘laparoscopy and twin ectopic’, ‘laparoscopy and twin tubal pregnancy’, ‘surgery and twin pregnancy’, ‘surgery and twin ectopic’, ‘surgery and twin tubal pregnancy’, ‘methotrexate and twin pregnancy’, ‘methotrexate and twin ectopic’, ‘methotrexate and twin tubal pregnancy’.

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when blastocyst implants outside the uterine cavity, being this true for both singleton and multiple pregnancies.

The first un-ruptured twin tubal pregnancy was described in 1986 by Santos (1). Ectopic pregnancy develops in almost 2% while twin pregnancy counts for 1 every 80 spontaneous pregnancies (2). Unilateral twin ectopic pregnancy is though a rare condition occurring with a frequency of 1/20.000-125.000 pregnancy and 1/200 ectopic pregnancy, rarer than expected (3-5). Moreover, ectopic pregnancy has a recurrence rate of 10% for one and 25% for two or more previous (6).

Although the trend for ectopic pregnancy has been constantly increasing over the past 30 years (mainly because of Assisted Reproductive Technology and epidemiological reasons), unilateral twin ectopic pregnancies have remained anneddoctical, just approximately 106 cases described in literature, out of whose only 8 cases had live twin 1 a year.

In addition the incidence is likely to be underreported because the diagnosis is primarily surgical (<10 out of 106 were diagnosed preoperatively) and/or pathological (consider the well-known phenomenon of the vanishing twin and the deterioration of the material after medical therapy) (7).

30 years ago the mortality due to ectopic pregnancy ranged between 72 to 90% while recently, mainly thanks to early diagnosis, it dramatically dropped to 0.14% (2).

Risk factors are basically all conditions that might impaire the migration of the blastocyst/embryo to the endometrial cavity by distorting tubal anatomy i.e. prior pelvic inflammatory disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, tubal surgery or ligation, assisted reproductive technology and also congenital anomalies.

Other factors are, although less counting, increasing age, smoking, intrauterine contraceptive device and defects of the zygote itself or in the hormonal milieu (8). The most common type of twin ectopic pregnancy is the heterotopic (1/7000 pregnancies) in which in which both ectopic and intrauterine pregnancy occur simultaneously (1).

Based on case reports from the literature, monozygotic and monoamniotic are the most frequent (95%) among unilateral twin tubal pregnancies, nonetheless a DNA analysis theorized that many of these might be dizygotic (3). The delay in tubal transport may play a role in the extensiveness of unilateral twin ectopic implantation; conversely it has been also supposed that the larger size of the twin cell mass itself causes the transport retard (9). Some authors explain the twin ectopic pregnancy as a mere result of a bilateral ovulation. Just like in singleton ectopic pregnancy, fallopian tube is the most common site.

Compared to a same sized singleton pregnancy, the chance of rupture for a twin ectopic one are lower as trophoblastic invasion may be less due to lower gestational age at presentation in the latter case. Being somehow similar and somehow different, the management of twin ectopic pregnancy can’t just mirror the singleton one. The symptoms of the classic triad of amenorrhea, vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain are all presents in less than half patients.

Risk factors can prop up the diagnosis, especially a previous ectopic implant.

Serum βhCG can be much higher than the well-know discriminatory zone of 1500-2000 mIU/ml valid for singleton ectopic pregnancy (with a mean of 9846), due to the larger trophoblastic tissue (10). Interestingly, the value can thus resemble to the ones of normal intrauterine pregnancies: in the absence of an intrauterine gestational sac and normally rising βhCG the chance of a twin ectopic implant has to be considered, even if rare. The majority of tubal ectopic pregnancies are detected by transvaginal ultrasound with a sensitivity of 87.0-99.0% and a specificy of 94.0-99.9%.

In some cases the evaluation, even combining all the informations, is not discerning: the pregnancy is then classified of unknown location (PUL). The echographic signs might be, as well as in singleton ectopic implants, divided into direct and indirect. The only direct sign is the identification of a non homogeneous or solid-cystic adnexal mass encompassing two thick-walled fluid-filled cystic masses, formed by the gestational sacs (yolk sac and/or embryo are less often visualized than in singleton).

Indirect signs are the same as singleton: no evidence of intrauterine sac, fluid in the pouch of Douglas; sometimes fluid collects in the uterine cavity appearing as so-called ‘pseudosac’.

Management

The primary goals are fertility preservation (being the main predictive factor the status of the controlateral tube at surgery) and avoidance of unfavorable outcome as tubal rupture (9).

As reported by Mol, “laparoscopic surgical approach in the most cost-effective method for treating ectopic pregnancy, but in carefully selected cases, the use of systemic MTX is proved to be a great alternative with similar success rates, and it is completely non-invasive (11). Moreover, some studies agreed that medical treatment doesn’t impair tubal patency nor the ovarian reserve (it might spoil oocyte production but temporarily) (12-13).

Lastly, as reported by Menon, “rates of treatment failure are substantially and statistically greater if the initial values of βhCG exceed 5000 mIU/ml”, simultaneously the higher the level, the higher the risk for tubal obstruction (11).

Summarizing, expectant, medical and surgical therapy have similar success rates in correctly selected patients (14).

Two prospective randomized trials did not identify any statistically significant differences between groups receiving MTX as a single dose or in multiple doses (15,16).

Among the 106 cases reported in literature, methotrexate was tried just in 4 patients (3 unilateral and 1 bilateral) before ours. Details are reported in the table 1 (6, 17, 18).

Table 1.

Previous reported cases in literature

| Patient, Year | Gestation Days | Day 0 Bhcg | U/B | Crl Diameter-mm | MTX -TR | DOF | Simptoms | Blood-loss | Bhcg (before surgery) | Result |

| 1, 1993 | 77 | 3640 | U | 25 × 30; Crl 11 and 13 | 31.5 mg of MTX Into Each Gestational Sac; 2 Days Later a Systemic Dose Of 63 Mg (IM) | 31 | - | S | ||

| 2, 1997 | Unsure | 539 | B | Diameter 25 | Single Dose 50 Mg/M2) | 4 | Acute Abdomen | 100 | U | |

| 3, 2008 | Non Reported | 763 | U | Not Reported | Multiple Dose Regimen (1 Mg/Kg on Days 1,3,4 and 7 + 0.1 Mg/Kh of Folinic Acid on Days 2,4,6 and 8) + a Single Dose on Day 14 Th (1 Mg/Kg) | 32 | - | S | ||

| 4, 2009 | 49 | 18780 | U | CRL 11 Ans 8 Mm | Single Dose (1 Mg/Kg) | 42 | - | S | ||

| Ours, 2016 | 44 | 13217 | U | 5 and 16 | Multiple Dose (50 Mg/Mg) on Day 1, 7 and 14 + Folic Rescue (5 Mg/Die Per Os) | 18 | Acute Abdomen | 2500 | 3659 | U |

CRL: Crown-rump length; DOF: Duration of follow-up; U/B: Unilateral/Bilateral; U/S: Success/unsuccess; MTX-TR: Methotrexate Treatment Regimen

Conclusions

When making a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, even though rare, the chance of twin implant has to be considered. The recent shift in the treatment of singleton ectopic pregnancies to the less invasive medical therapy might apply even in the case of twin implants.

References

- 1.Santos CA, Sicuranza BS, Chatterjee MS. Twin tubal gestation diagnosed before rupture. Perinatol Neonatol. 1986;10:52–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dede M, Gezginç K, Yenen M, Ulubay M, Kozan S, Güran S, Başer I. Unilateral tubal ectopic twin pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;47(2):226–8. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goswami D, Agrawal N, Arora V. Twin tubal pregnancy: A large unruptured ectopic pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(11):1820–2. doi: 10.1111/jog.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam T, Khazaei A. Spontaneous unilateral dizygotic twin tubal pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009 Feb;Feb(37):2–104. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vohra S, Mahsood S, Shelton H, Zaedi K, Economides DL. Spontaneous live unilateral twin ectopic pregnancy - A case presentation. Ultrasound. 2014;22(4):243–6. doi: 10.1177/1742271X14555565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghanbarzadeh N, Nadjafi-Semnani M, Nadjafi-Semnani A, Nadjfai-Semnani F, Shahabinejad S. Unilateral twin tubal ectopic pregnancy in a patient following tubal surgery. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(2):196–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamane D, Stella M, Goralnick E. Twin ectopic pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 2015 Jun;48(6):e139–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker J, Hewson AD, Calder-Mason T, Lai J. Transvaginal ultrasound diagnosis of a live twin tubal ectopic pregnancy. Australas Radiol. 1999;43(1):95–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.1999.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hois EL, Hibbeln JF, Sclamberg JS. Spontaneous twin tubal ectopic gestation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(7):352–5. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eddib A, Olawaiye A, Withiam-Leitch M, Rodgers B, Yeh J. Live twin tubal ectopic pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93(2):154–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.02.009. Epub 2006 Mar 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cecchino GN, Araujo Júnior E, Elito Júnior J. Methotrexate for ectopic pregnancy: when and how. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(3):417–23. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elito J, Han KK, Camano L. Tubal patency after clinical treatment of unruptured ectopic pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 205;88:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oriol B, Barrio A, Pacheco A, Serna J, Zuzuarregui JL, Garcia-Velasco JA. Systemic methotrexate to treat ectopic pregnancy does not affect ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1579–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juneau C, Bates GW. Reproductive outcomes after medical and surgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(2):455–60. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182510a88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alleyassin A, Khademi A, Aghahosseini M, Safdarian L, Badenoosh B, Hamed EA. Comparison of success rates in the medical management of ectopic pregnancy with single-dose and multiple-dose administration of methotrexate: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1661–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guvendag Guven ES, Dilbaz S, Dilbaz B, Aykan Yildirim B, Akdag D, Haberal A. Comparison of single and multiple dose methotrexate therapy for unruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy: a prospective randomized study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:889–895. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.486825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S, Mol BW, Van der Veen F, Ankum WM, Bossuyt PM, Hemrika DJ, Lammes FB. Randomised trial of systemic methotrexate versus laparoscopic salpingostomy in tubalpregnancy. Lancet. 1997;350(9080):774–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arikan DC, Kiran G, Coskun A, Kostu B. Unilateral tubal twin ectopic pregnancy treated with single-dose methotrexate. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(2):397–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]