Abstract

Background and aim: Unplanned extubation (UE) in Intensive Care Units (ICU) is an indicator of quality and safety of care. UEs are classified in: accidental extubations, if involuntarily caused during nursing care or medical procedures; self-extubation, if determined by the patient him/herself. In scientific literature, the cumulative incidence of UEs varies from 0.3% to 35.8%. The aim of this study is to explore the incidence of UEs in an Italian university general ICU adopting a well-established protocol of tracheal tube nursing management and fixation. Methods: retrospective observational study. We enrolled all patients undergone to invasive mechanical ventilation from 1st January 2008 to 31st December 2016. Results: in the studied period 3422 patients underwent to endotracheal intubation. The UEs were 35: 33 self extubations (94%) and 2 accidental extubations (6%). The incidence of UEs calculated on 1497 patients intubated for more than 24 hours was 2.34%. Instead, it was 1.02%, if we consider the whole number of intubated patients. Only in 9 (26%) cases out of 35 UEs the patient was re-intubated. No deaths consequent to UE were recorded. Conclusions: The incidence of UEs in this study showed rates according to the minimal values reported in scientific literature. A standardized program of endotracheal tube management (based on an effective and comfortable fixing system) seems to be a safe and a valid foundation in order to maintain the UE episodes at minimum rates.

Keywords: unplanned extubation, self extubation, accidental extubation, adverse events

Background and aim

Intensive care units (ICU) are settings with a high risk of adverse events related to patients’ interferences with the treatment. Treatment interference is a concept which involves the self-removal of support or monitoring devices at various levels of invasiveness and it can determine clinical consequences with different levels of severity (1). Nurses perceive the burden of responsibility in protecting the patient from injuries and keeping the integrity of the devices, especially arterial catheters, venous catheters and endotracheal tube (1). Concerning the adverse events with endotracheal tubes, there is not only the risk of self extubation (SE), but also of accidental extubation (AE). AE is the extubation caused accidentally by healthcare workers during nursing or medical procedures. SE and AE are phenomena gathered under the whole concept of unplanned extubations (UEs) (2).

UEs are conditions with high relevance for ICU patients’ safety issues. A work group on patients’ safety of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine has recognized the UEs as quality care indicators because they are related to high rates of reintubation, increased nosocomial pneumonia incidence, and death (3-5). The AEs are often the result of errors occurred during the change of patient’s position, or tracheal tube handling and fixation. The SE, instead, can be due to failure in surveillance of the patients, or to the missed identification of the criteria to start the weaning from mechanical ventilation and subsequent extubation (3, 6).

Overall, the UEs in adult ICU patients show a very floating incidence. A recent systematic review of the literature shows a rate varying from 0.5% to 35.8% (7). In the studies using the incidence density rate to describe the phenomenon, the range is from 0.1 to 4.2 cases every 100 days of ventilation (7). The incidence density rate is the desirable indicator to compare different settings. The SEs characterize the larger part of UEs. In fact their incidence varies from 50% to 100% of all UEs (7).

The most important risk factors for UEs are (in a decreasing order): APACHE II score ≥17, patient’s agitation, physical restraints, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, use of midazolam, inadequate sedation and altered state of consciousness (7-9). Furthermore, some intrinsic risk factors have also been studied (e.g. age, gender and body mass index), but their role is still unclear (10).

Lastly, although there is no evidence about the superiority of one kind of tube fixation method over others, a weak fixation has also been acknowledged as a risk factor for UEs (10-12).

A survey performed in U.S. has showed that healthcare workers (doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists) considered risk factors for UEs the following conditions: the absence of physical restrain, a nurse patient ratio of 1:3, the trips out of ICU, light sedation, bedside radiographies and the night shift (13). The night shift seems to be an influential risk factor for UEs (Odds Ratio: 6.0-95% CI: 3.65-10.03), according to a case-control study carried out on 690 patients in Chorea (14).

The UE complications occurrence varies from 14% to 35% and can be related to problems concerning airway management (difficult laryngoscopy, esophageal intubation), respiratory system (tachypnea, hypoxemia, Ventilator Associated Pneumonia) and hemodynamic (tachycardia, hypertension, hypotension) (2, 3, 15).

The negative consequences of UEs can determine the increase of ventilation days, and the ICU and hospital lengths of stay (2, 3, 15). In scientific literature there are some ambiguous data about mortality related to UEs. An observational study on SE patients showed a difference of 22% in mortality rates of patients who had a UE compared with those who underwent to a well-planned extubation (p<0.01) (16).

The SE patients undergo to reintubation in a range from 0% to 63%, while those who experienced an AE can be reintubated up to 100% of the cases (3, 17). However, reintubation is an event which generally occurs immediately after the UE. In fact, 74% of the cases it is accomplished within an hour from the time of UE (3).

The need of reintubation is not different between medical and surgical patients (respectively 3.4%-74% and 22.6%-88%). Instead, there are lower reintubation rates in patients during weaning from mechanical ventilation (max 30%) when compared with those who are under a full ventilation support at the moment of UE occurrence (max 81%) (3).

Nevertheless, reintubation after UE is strongly associated to the rise of hospital expenses consequent to the increase of ventilation days and ICU length of stay (18).

Currently there are no data about UE from Italian ICU settings, except for a recent qualitative study exploring the phenomenon (19). For these reasons, a study to analyze the incidence and risk factors of UEs was performed in an Italian general ICU.

Material and methods

Study design and aims

An observational retrospective study was designed. The primary aim was to record the incidence of AE and SE. The secondary aims were to identify the outcomes of UE patients and the risk factors.

Sample

All the intubated patients in the general ICU of the San Gerardo Hospital in Monza were enrolled from the 1st January 2008 to the 31st December 2016. This ICU admits patients from the emergency room and operating theatre; moreover, it is an Italian referral center for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation support.

The UEs events were distinguished into: self extubation (SE) and accidental extubation (AE).

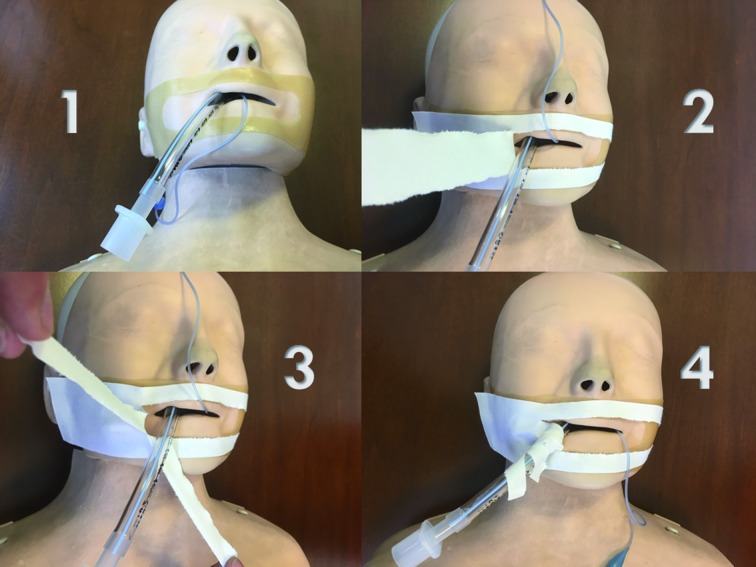

The endotracheal tube fixation in the enrolled patients was made according to the well-established local ICU procedure. In orotracheal intubated patients the fixing system is performed using a 5 cm tape (Durapore®), cut as shown in figure 1. Under the tape, the nurse applies a thin hydrocolloid film (Duoderm extrathin®) to protect the patient’s face skin, preventing the occurrence of pressure ulcers. This dressing is changed every 12 hours (at 8 am and 6 pm) and, simultaneously, the endotracheal tube is moved from a mouth side to the other. In nasotracheal intubated patients the fixing system is performed through of the utilization of a 1 cm tape (Durapore®) and the application of a thin hydrocolloid film (Duoderm extrathin®) to protect the skin of the patient’s nose and the nostril. This dressing is usually changed every 24 hours. In these patients the oral care is carried out three times a day.

Figure 1.

Data collection

The study data were collected from a dedicated section of the electronical clinical documentation. The collected respiratory parameters, ventilation settings and administered medications were those recorded one minute before the occurrence of UE. The electronic integrated clinical documentation system records patients’ data every 60 seconds. The analysis of patients’ sedation levels was performed using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) (20), as routinely done in the studied ICU. RASS evaluates the patient’s level of consciousness, sedation or agitation. The score varies from 0 (alert and calm) to +4 (combative) for awake patients. If the patient is not awake, the score varies from -1 (drowsy), to -5 (unarousable) (20).

During the study period RASS was measured every four hours. The last value of RASS scale before the UE was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and transposed on an xls file, and analyzed by the software SPSS ver. 22.0 for Windows©. The variables were analyzed as mean, standard deviation and range or median and interquartile interval, according to the type of statistical distribution. The comparison among groups was performed through non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney test). A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was submitted to the Local Ethical Committee and approved by the act number 874 on 15th May, 2018.

Results

In the studied period 3422 patients underwent to endotracheal intubation. The patients with an intubation duration time higher than 24 hours were 1497 (43.7%). The mean age of the patients was 66.12±20.22 years, with a mean ICU stay of 5.57±10.30 days (median 2, Q1-Q3: 1-5 days). The admission diagnosis was medical in 46% (n=1574) and surgical in 54% (n=1848) of the patients. The UEs were 35: 33 SEs (94%) and 2 AEs (6%). The UE incidence on the 1497 patients with an intubation duration time higher than 24 hours was 2.34%. The percentage of UE decreases to 1.02% if calculated on all the intubated patients’ population. For the years 2014, 2015 and 2016 we could estimate the incidence density of UEs. In these three years the density incidence was 0.31 for 100 ventilation days. Table 1 summarizes the cases of UE divided for years of occurrence. At the time of the UE occurrence, the patients had a median RASS of 0 (Q1-Q3: -2/0), a mean propofol dosage of 84.2±140.9 mg/h (in 7 patients), a mean midazolam dosage of 2.1±1.1 mg/h (in 4 patients) and a mean fentanyl dosage of 34.9±35 mcg/h (in 16 patients). A physical restrain by wrists lock was present in 17 (48.6%) patients. The other 18 (51.4%) UE patients were not restrained at the time of the event. At the time of the UEs, the ventilators settings were: Volume Controlled Ventilation in 2 (6%) cases (AE events – pediatric patients, events occurred during hygienic care); Pressure Support Ventilation with sigh in 15 (43%); Pressure Support Ventilation in 8 (23%); Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in 10 (29%). Table 2 summarizes the ventilation settings at the time of the UE events. Only 9 patients (26%) were reintubated. Eight patients were reintubated within an hour from the UE occurrence, while one patient was reintubated after 11 hours. In the 26 patients who were not reintubated, the respiratory supports used after the UE were: oxygen reservoir mask - 1 (4%), Venturi mask - 12 (46%), and helmet CPAP - 13 (46%).

Table 1.

Events per years

| Year | SE AE | Total UE | Intubated patients | (Patients >1 day mechanical ventilation) | % UE | Ventilation days | UE rate every 100 days of mechanical ventilation | Reintubated patients | ||

| n. | % | |||||||||

| 2008 | 6 | 6 | 273 | 204 | 2.20 | 1 | 17 | |||

| 2009 | 5 | 5 | 470 | 179 | 1.06 | 1 | 20 | |||

| 2010 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 389 | 248 | 1.29 | 2 | 40 | ||

| 2011 | 2 | 2 | 402 | 219 | 0.50 | 1 | 50 | |||

| 2012 | 1 | 1 | 372 | 198 | 0.27 | 0 | ||||

| 2013 | 2 | 2 | 318 | 213 | 0.63 | 1 | 50 | |||

| 2014 | 3 | 3 | 361 | 236 | 0.83 | 1410 | 0.2 | 0 | ||

| 2015 | 7 | 7 | 407 | 264 | 1.72 | 1505 | 0.47 | 2 | 29 | |

| 2016 | 4 | 4 | 430 | 171 | 0.93 | 1506 | 0.27 | 1 | 25 | |

| Total | 33 | 2 | 35 | 3422 | 1497 | 1.02 | 0.31 | 9 | 26 | |

Legend: AE: accidental extubation; SE: self extubation; UE: Unplanned extubation

Table 2.

Respiratory parameters before unplanned extubations events

| Parameters | Average (SD) | Range |

| Sigh Frequency rate (15 pts) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.5-1 |

| Sigh Pressure - cmH2O (15 pts) | 29.9 (11.0) | 25-36 |

| Pressure Support Ventilation cmH2O (24 pts) | 9 (3.3) | 4-14 |

| PEEP cmH2O | 7.6 (2.9) | 4-15 |

| RR | 19.2 (5.8) | 9-33 |

| FiO2 | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.3-1 |

| PO2mmHg | 108 (112) | 62-208 |

| PO2/FiO2 | 264 (112) | 62-693 |

| SpO2 % | 97.4 (1.7) | 94-100 |

Legend: FiO2: Fraction Of Inspirated Oxygen; PEEP: Positive Ending Expiratory Pressure, PO2: Partial Pressure Of Arterial Oxygen; RR: Respiratory Rate; SpO2: periferical oxygen saturation

In order to identify specific risk factors for reintubation after UE occurrences, an analysis of the differences in the parameters between the non-reintubated patients and the reintubated patients was performed. The respiratory rate (RR) before the UE event was higher in the reintubated patients’ group than the non-reintubated group (24.2±4.5 vs. 18.0±5.2 breaths/min. – p=0.005). Besides, the reintubated patients had a lower mean RASS value (-2.1±0.75 vs -0.3±1.3 – p=0.004).

We did not find statistically differences between the ventilation settings, the oxygenation levels and ventilation days in the two compared patients’ group. Table 3 summarizes all the investigated variables in the two subgroups. No episode of death related to UE was recorded in the 9 years observed.

Table 3.

Comparison between non-reintubated patients versus reintubated after unplanned extubation events

| No Reintubated Patients N=26 | Reintubated Patients n=9 | P value | ||

| Age | 63.7 (16.5) | 47.1 (30.9) | 0.054 | |

| Intubation Days | 4.9 (4.8) | 4.6 (3.9) | 0.875 | |

| Mode Of Ventilation | CPAP | 10 (38%) | 2 (25%) | 0.986 |

| PS | 5 (19%) | 3 (38%) | ||

| Sigh+CPAP | 2 (8%) | 1 (13%) | ||

| Sigh+PS | 9 (35%) | 2 (25) | ||

| Sigh | 6 (26%) | 6 (75%) | 0.434 | |

| PS | 9.2 (3.0) | 8.5 (4.0) | 0.647 | |

| PEEP | 7.1 (2.0) | 8.2 (2.8) | 0.241 | |

| RR | 18.0 (5.2) | 24.2 (4.5) | 0.005 | |

| pO2 | 156 (214) | 98 (18) | 0.455 | |

| FiO2 | 0.43 (0.7) | 0.41 (0.7) | 0.571 | |

| P/F | 281(121) | 240 (53) | 0.365 | |

| SpO2 | 97.6 (1.6) | 97.0 (1.5) | 0.355 | |

| RASS | -0.3 (1.3) | -2.1 (0.75) | 0.004 |

Legend: CPAP: Continous Positive Airway Pressure, FiO2: Fraction Of Inspired Oxygen PEEP: Positive End Expiratory Pressure, P/F: PO2/FiO2 ratio, PS: Pressure Support, PO2: Partial Pressure Of Arterial Oxygen, RASS: Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale, RR: Respiratory Rate, SpO2: Periferical Oxygen Saturation,

Discussion

The incidence of UEs reported by this study (1.02%) is similar the lowest UE values reported in literature (range from 0.5% to 35.8%). According to the international literature, in the studied sample most of the UEs were caused by the patients (94.3%), while only 5.7% was provoked by the healthcare workers.

The low incidence of the UEs found in this study could be affected by the appropriate nurse to patient ratio (1:2), kept as a constant work standard 24 hours a day (21). Moreover, the use of a protocol for endotracheal tube management shared by the whole staff (22) which has an efficient fixing system could have been a protective factor. These two variables probably allowed a sufficient level of patient’s direct surveillance, and the prevention of the loss of the stability of the endotracheal tube.

No UEs happened during the oral care performance or during the change of the tube fixing system. These data confirm the safety of the recommendation to carry out these nursing procedures more than once per day. However, in order to accomplish this task maintaining a good control of the risk for the patient, it’s mandatory to follow the procedure using an adequate level of attention. The patients with the highest risk of UE complications are those at the beginning of the respiratory weaning. In fact, at the time of the interruption of the sedation infusions, the patients could be agitated and confused and trying to self-remove the devices, since their presence can provide discomfort and pain.

However, the AEs remain the potentially most dangerous events because the patient often doesn’t show an efficient respiratory drive to provide a valid spontaneous breathing. In fact, 2 patients (100%) were reintubated within an hour from the time of the event. On the contrary, the SE patients were more awake and with lower ventilator support parameters (6, 12); therefore, only 21.2% was reintubated. About SE events, there were no sufficient data to demonstrate the occurrences of some delays in the identification of extubation citeria (success predictors of spontaneous breathing trial).

The physical restrain is a tool with ambiguous effectiveness in preventing SEs because half of the patients (48%) succeeded in removing the endotracheal tube. In the literature the usefulness of physical restrain systems as preventive measures for the removal of medical devices is still discussed (15, 23).

Concerning the issue of patients’ surveillance, the studied ICU is an open space type. This design could have exerted an influence on the low incidence of SEs, allowing an immediate awareness of the impending danger of SE and the consequent prevention of this kind of event. Currently, this consideration should deserve empirical demonstration, because there are no published studies comparing open bay ICUs and single box ICUs in terms of UE occurrence rates.

This study showed statistically significant differences in the mean RASS (p=0.004) score and in the mean RR (p=0.005) between UE patients undergone to reintubation versus those who were not reintubated. In fact, the reintubated patients had higher RR and lower RASS scores. These elements confirm the need of paying adequate attention to clinical evaluation (level of consciousness, breathing) immediately after the UE, besides the instrumental data which sometimes can be misleading. For example, patients during hypoxemic respiratory distress can maintain appropriate oxygen saturation values, at the cost of large increases of their RR.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First of all the retrospective design didn’t allow systematically to gather some potentially important data such as the number of nasotracheal intubated patients, even if we can affirm that they were surely the minor part of the studied sample. Besides, there was not the possibility to know the number of physical restrains implemented in the patients who did not undergo to UEs, thus limiting the possibility of making statistical comparisons. Lastly, the very low incidence of the UEs probably affected the level of statistical significance for the comparison of the subgroups of patients with AE versus SE, and reintubated versus no reintubated.

Conclusions

The incidence of UEs in the studied setting showed rates according to the minimal values reported in scientific literature. Furthermore, no episodes of death related to UEs occurred. Patients with lower RASS values and higher respiratory rates are likely to be reintubated after a UE event. A standardized program of endotracheal tube management (based on an effective and comfortable fixing system) seems to be a safe and a valid foundation to maintain low rates of UE episodes.

The results of this study seem to indicate that the patient’s surveillance cannot be substituted by the utilization of physical restrains in order to prevent SE events.

The study was performed at General Intensive Care Unit of S. Gerardo Hospital, Monza (Italy).

References

- 1.Happ MB. Preventing treatment interference: the nurse’s role in maintaining technologic devices. Heart Lung. 2000;29:60–9. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(00)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bambi S. Le estubazioni non pianificate nelle terapie intensive: quali implicazioni per l’assistenza infermieristica? Assist Inferm Ric. 2004;23:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhodes A, Moreno RP, Azoulay E, Capuzzo M, Chiche JD, Eddleston J, et al. Prospectively defined indicators to improve the safety and quality of care for critically ill patients: a report from the Task Force on Safety and Quality of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:598–605. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stalpers D, De Vos MLG, Van Der Linden D, Kaljouw MJ, Schuurmans MJ. Barriers and carriers: a multicenter survey of nurses’ barriers and facilitators to monitoring of nurse-sensitive outcomes in intensive care units. Nurs Open. 2017;4:149–156. doi: 10.1002/nop2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riera A, Gallart E, Vicálvaro A, Lolo M, Solsona A, Mont A, et al. Health-related quality of life and nursing-sensitive outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients in an Intensive Care Unit: a study protocol. BMC Nurs. 2016;5(15):8. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González-Castro A, Peñasco Y, Blanco C, González-Fernández C, Domínguez MJ, Rodríguez-Borregán JC. Unplanned extubation in ICU, and the relevance of non-dependent patient variables the quality of care. Rev Calid Asist. 2014;29:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cali.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Silva PSL, Fonseca MC. Unplanned endotracheal extubations in the intensive care unit: systematic review, critical appraisal, and evidence-based recommendations. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1003–14. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824b0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai ZP, Gao XL, Zhao XL. Factors associated with unplanned extubation in the Intensive Care Unit for adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;47:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aydoğan S, Kaya N. The Assessment of the Risk of Unplanned Extubation in an Adult Intensive Care Unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36:14–21. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosentino C, Fama M, Foà C, Bromuri G, Giannini S, Saraceno M, et al. Unplanned extubations in Intensive Care Unit: evidences for risk factors. A literature review. Acta Biomed. 2017;88:55–65. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i5-S.6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley JC, Brown AP, Shin JS, Rogers KM, Hoftman NN. A Comparison of the Haider Tube-Guard® Endotracheal Tube Holder Versus Adhesive Tape to Determine if This Novel Device Can Reduce Endotracheal Tube Movement and Prevent Unplanned Extubation. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1439–43. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner JL, Shandas R, Lanning CJ. Extubation force depends upon angle of force application and fixation technique: a study of 7 methods. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;24(14):74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanios MA, Epstein SK, Livelo J, Teres D. Can we identify patients at high risk for unplanned extubation? A large-scale multidisciplinary survey. Respir Care. 2010;55:561–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon E, Choi K. Case-control Study on Risk Factors of Unplanned Extubation Based on Patient Safety Model in Critically Ill Patients with Mechanical Ventilation. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2017;11:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee TW, Hong JW, Yoo JW, Ju S, Lee SH, Lee SJ, et al. Unplanned Extubation in Patients with Mechanical Ventilation: Experience in the Medical Intensive Care Unit of a Single Tertiary Hospital. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015;78:336–40. doi: 10.4046/trd.2015.78.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuang ML, Lee CY, Chen YF, Huang SF, Lin IF. Revisiting unplanned endotracheal extubation and disease severity in intensive care units. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiung Lee ES, Jiann Lim DT, Taculod JM, Sahagun JT, Otero JP, Teo K, et al. Factors Associated with Reintubation in an Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective Observational Study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21:131–137. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_452_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontenot AM, Malizia RA, Chopko MS, Flynn WJ, Lukan JK, Wiles CE, Guo WA. Revisiting endotracheal self-extubation in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit: Are they all fine? J Crit Care. 2015;30:1222–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danielis M, Chiaruttini S, Palese A. Unplanned extubations in an intensive care unit: Findings from a critical incident technique. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;47:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bambi S, Rodriguez SB, Lumini E, Lucchini A, Rasero L. Unplanned extubations in adult intensive care units: an update. Assist Inferm Ric. 2015;34:21–9. doi: 10.1702/1812.19748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chao CM, Sung MI, Cheng KC, Lai CC, Chan KS, Cheng AC, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of unplanned extubation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8636. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08867-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiekkas P, Aretha D, Panteli E, Baltopoulos GI, Filos KS. Unplanned extubation in critically ill adults: clinical review. Nurs Crit Care. 2013;18:123–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]