Abstract

Background: Thousands of caregivers around the world take care of impaired people, with negative repercussions on their physical, psychological, social and economic resources. The need to promote caregivers’ wellbeing is internationally recognized, thus reducing health inequalities. Mindfulness is a powerful tool, directly related to the reduction of stress, able to increase skills and attitudes promoting well-being. The basis of this project of community development based on active health, is the self-care achieved through mindfulness. Aims: The overall aim of this project is to improve the caregivers’ health and quality of life through community mapping strategies and mindfulness. Methods: According to the salutogenic model, and to the model of community development based on active health (ABCD) we will create a map of the caregivers’ internal and external health assets. The project will have a participatory action research methodology, and it will go throygh five different phases, with mindfulness as a central tool. Results: At the end of the project, results will be analyzed referring to structures, processes and objective and subjective outcomes. Conclusions: At the end of the project, we will evaluate if the Salutogenic ABCD methodology along with Mindfulness, will be able to reduce health inequalities improving caregivers’ wellbeing.

Keywords: assets, caregiver, Mapping party, Mindfulness, Salutogenesis, self-care

Introduction

All over the world, thousands of people need continuous assistance, and thousands of people have to take care of them. These are the caregivers, and it is estimated that there are 225,000 only in Spain, almost always women with an average age between 50 and 70 years. The evidence shows the negative repercussions on physical, psychological, social and economic resources that caring for others can have on these people. However, social, cultural, economic factors and factors such as gender are, in this case, much more relevant and determinant in the health disparities of the caregivers’ population (1). Different strategies at national and European level recognize the need to promote care for caregivers. The caregiver must take care of himself to guarantee a good level of care for another person but above all to maintain his health and well-being. But to take care of himself he must be able to ask for help, and request support from professionals and from his networks. The term Mindfulness taken from the Pali language, meaning full awareness or conscious attention to the present moment (2), is considered as one of the most powerful “tools” for understanding one’s own thoughts, emotions, and body signals, directly related, not only with the reduction of stress levels, but also with the increase of skills and attitudes (empathy, self-awareness, calm, concentration, attention, kindness) that promote well-being in people who practice it (3).

Mindfulness is also a lifestyle. A way of “being” against the “doing” way, continuously activated in the West countries. In other words, Mindfulness is a life philosophy. Practicing Mindfulness in a continuous way, encourages the development of this philosophy, and so, over time, can become a stable characteristic making the person “Mindful”, that means with an attitude of (4-5): curiosity for mental contents, acceptance of the present moment, openness to mental contents, no judgment towards the present experience, detachment, and kindness / love / affection. Therefore, an attitude of self-care and self-acceptance in the present moment, without which it is really difficult to develop full awareness.

Specifically, Minfulness is based on the practice of exercises (or meditations), centered on three fundamental pillars: Samatha (attention, concentration, calm), Vipassana (contemplation, mental clarity) and Metta (loving kindness).

At the beginning of Mindfulness practice, people perform Samatha exercises, to learn to keep their attention on a specific point in a quiet state, becoming aware of what happens. Subsequently Vipassana is practiced, including the contemplation of mental contents (thoughts, emotions) with an attitude on letting them flow freely. However, Metta is the prerequisite of the whole practice, as Mindfulness implies a person being always in a state of loving kindness, goodness, affection, and benevolence towards himself.

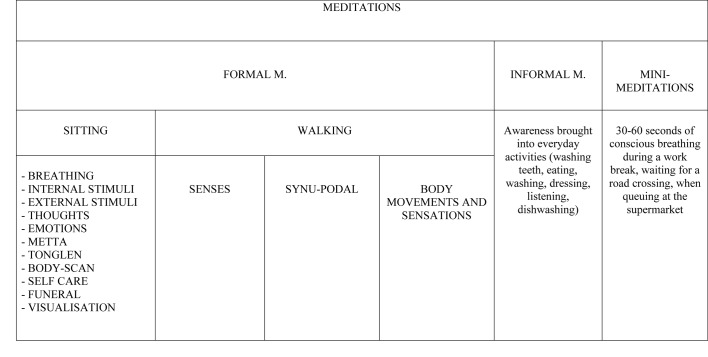

The different meditation exercises (fully shown in in table 1) can basically be divided into:

Table 1.

List of Mindfulness Meditations

1. - Formal meditations.

a) Sitting practices: meditations linked to the breath, to internal and external stimuli, to thoughts and emotions (Tonglen, Metta, Body-Scan)

b) Standing practices: walking meditations or conscious walking including “sensory”, “synupodal rhythm” and “bodily movements and sensations”.

2. - Informal meditations

Practices carried out taking advantage of any action put into practice during the day, being fully aware as brushing teeth, eating, listening to someone

3. - Mini-meditations.

Very short exercises (usually focused on breathing) performed at different times of the day.

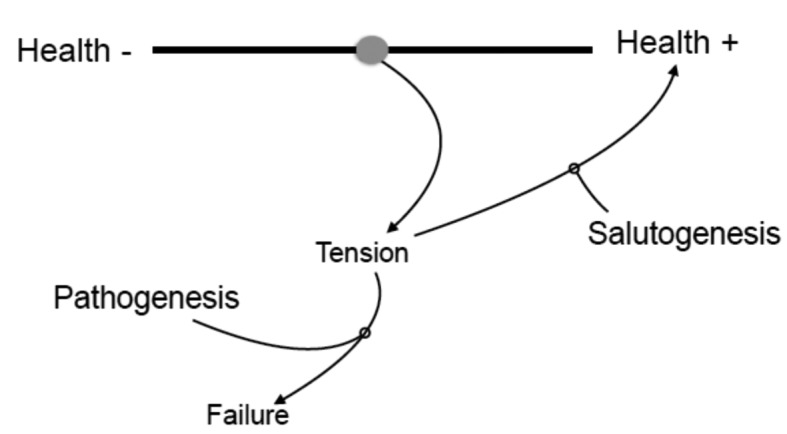

Practicing Mindfulness can change the relationship of a person with himself, also learning to respond in a different way to stressful situations, encouraging adjustment. This process of empowering one’s resources in favor of a better adjustment is extremely close the “salutogenic model” (6), which shows how people who are able to adjust to stressful situations can maintain a good health. Antonovsky identifies among the characteristics underlying the ability to promote health, the sense of coherence, as “a person’s view of life and capacity to respond to stressful situations. It is a global orientation to view as structured, manageable, and meaningful. It is a personal way of thinking, benefit and use, and re-use the resources at their disposal “(7). We can therefore find a great affinity between this characteristic and the awareness of rising from practicing Mindfulness. Awareness seems to offer people the resources and opportunities to move towards the health pole on the Antonovsky’s continuum (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antonovsky’s continuum

Furthermore, Mindfulness also seems to have a direct connection with the health-related conceptual framework of health developed by Morgan and Ziglio (8). According to this framework a health asset is “any factor or resource that increases the capacity of individuals, communities or populations to maintain health and well-being”. According to Botello and col., health assets can be connected to people, organizations and associations, institutions, economy, culture and available infrastructures (9). However, in the ABCD “Assets Based Community Development” methodology, the first basic component of assets is the individual one given by capacities, abilities and gifts of every single person (10, 11). Mindfulness can be central in the identification of these characteristics, which require self-awareness, together with a self-care attitude that allows to identify the best decisions and actions for oneself moment by moment.

As previously mentioned, the task of taking care of others is a complex activity. It requires dedication, often exclusive, so that the person treated is in the best physical, emotional and environmental conditions. This requires caregivers to use a multitude of resources and skills, psychological, behavioral, and attitudinal. These resources can be more or less developed in each caregiver, and require a great awareness of himself and of his own state, to prevent the onset of burnout related to his role (12-13).

But far more important, the caregiver needs to learn how to take care of himself.

On a cognitive level (thoughts), self-care means being able to identify thoughts accepting them, with the awareness of not being the thought itself. On an emotional level (emotions), self-care involves the identification of the emotion in the body, giving it an origin (internal and / or external) and labeling it. This can allow the person to find out which behavior is triggered by this emotion and the consequences it could have, from a perspective of acceptance and benevolence towards any kind of emotion. On a social level, self-care means being able to reconnect with one’s own, personal priorities. Exactly in this aspect, the practice of Mindfulness can lead to a significant improvement in life and in carrying out of the role of caregiver. So the basis of this proposed community development project, focused on the identification of health assets, is self-care.

Aims

Overall aim

The main aim of this project is to improve the health and quality of life, real and perceived, in caregivers, through community mapping strategies and Mindfulness.

Specific aims

- Identifying and enhancing individual and environmental resources that can be health assets for caregivers;

- Including caregivers in their salutogenic empowerment;

- Developing Mindfulness skills in caregivers;

- Encouraging and developing higher levels of personal self-care in caregivers;

- Strengthening the caregivers’ sense of coherence;

-Promoting networks and relationships, among caregivers providing mutual assistance, aid, and empowerment;

- Identifying elements that can be improved in the community and in the caregivers.

Methods

Starting from the salutogenic model, and using the tool of health assets mapping (according to the ABCD model of Kretzman & Mcknight), we will map the population, environment and logistic assets needed to promote this work perspective (14-18). The project proposed here, uses a participatory action research methodology. The target population will consist of female caregivers working the same environment (i.e. same neighborhood) and recruited in health houses, hospitals, palliative care structures, home care services. The project, clearly complex, needs several successive phases for a correct implementation.

PHASE 1 Definition of the Promoting Group (PG)

In this phase is defined the promoting group of the project and, subsequently, the group of targeted caregivers. This phase consists of three moments:

Moment 1: Searching for the PG

The PG will consist of health professionals directly connected with caregivers. These people may be part of the health staff of different clinics, health houses, hospitals, nursing homes, public and private non-profit organizations, entities that are dedicated to health care. The PG will be directly responsible for recruiting participants and monitoring the process.

Moment 2: Organization and training of the PG

Once the PG has been identified, the project will be explained in detail and the different roles will be defined. The fundamental principles of salutogenesis and of Mindfulness will be presented. At this moment of Phase 1 the GP will have to: participate in a Mindfulness course to learn the basics of full awareness (underlining the aspects of care and self-care), and acquire the minimum theoretical and practical knowledge to follow the project. Mindfulness exercises and full practices will be held by expert practitioners, preferably psychotherapists.

Moment 3: Recruitment and configuration of the Caregivers Group (CG).

The projects considers only one PG that will be in charge of recruiting the caregivers who will be part of the project. Once the CG has been identified, a session will be held to present and explain the project, the aims, the Mindfulness and the fundamental principles of salutogenesis. The CG will then begin to perform various Mindfulness practices (19) with a subsequent deepening of Samatha and Vipassana. Subsequently we will introduce practices related to relationships, gratitude and self-care, with Metta and Tonglen meditations. Finally, different types of walking meditation (of the senses, of the synupodal rhythm and of body movements and sensations) will be introduced.

PHASE 2: Organization and planning

In this phase the caregivers’ baseline levels of sense of coherence, perceived burden, quality of life, self-compassion and mindful attitude will be traced. An organizational agenda will also be defined, to finally proceed to the delimitation of the area to be mapped.

Moment 1: Test.

Compilation of questionnaires: Sense of Coherence (SOC; 20), Zarit Scale (ZS; 21) or Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS; 22), Cuestionario de Calidad de Vida de los Cuidadores Informales (23), Self-Compassión Scale (SCS; 24) and the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; 25).

Moment 2: Actualizing resources and agenda.

We will specify which resources (materials, time, and physical spaces) will be used to implement the project, together with a time schedule related to the conclusion of the project.

Moment 3: Delimitation of the Map.

We will define the internal and external areas that will be mapped:

1) Internal or personal resources promoting health: skills, abilities, characteristics, profiles, leisure time, passions, interests, personal relationships, defined using Mindfulness sessions and group therapy.

2) Existing external resources promoting health: organizations and associations, institutions, local economy, local culture, infrastructures and physical spaces, area (of the city, of the country, ...) where they will identify the external resources .

At this stage, the CG will continue to perform different Mindfulness exercises specifically designed to facilitate the identification of internal resources. To increase the participants’ familiarity with the maps, in this phase will be introduced formal and informal dynamic exercises of Mindfulness applied to the maps reading. At this stage, in order to allow participants to be more aware of the external resources, specific walking meditations will be practiced to facilitate the mapping party.

PHASE 3: Mapping party

This phase will be dedicated to the real mapping of the internal and external resources of each participant.

Moment 1: Practice of conscious walking (Walking Meditation).

This phase will begin with the realization of the three walking meditations directly related to the mapping party.

The walking meditations will be followed by general exercises of Samatha and Vipassana, by relational exercises of Metta and Tonglen to strengthen the emotional bonds and group cohesion, and by general self-care exercises.

Moment 2: Mapping party.

To help participants perform the actual mapping, several Mindfulness exercises will be performed immediately before the start of walking meditation, adapted according to the characteristics of the group.

Thereafter, the caregivers will be invited to go out together to the previously identified area (Phase 2, Moment 3) together with the PG. Once the identified area is reached, they will practice a conscious walk, identifying the different external health assets through observation of the context. This process will be videotaped for later analysis. The walking meditation session will also be an opportunity for caregivers to be more aware of some of their internal characteristics (skills, attitudes, interests, resources). Participants will be asked to share verbally or in writing what has emerged during the practice and they will be videotaped.

Moment 3: Identification of Assets.

At this point, the external resources identified (actual and potential) will be classified into six different types: individuals, associations and organizations, institutions, local economy, local culture and physical infrastructure and spaces (9).

After the implementation of the Mapping party, a meeting including PG and CG will be held, to share what happened during the walking meditation, with the visualization of the video realized and the sharing of the identified external assets. Finally, the external assets will be inserted in the map along with the other potential external resources that need to be improved in order to become proper assets.

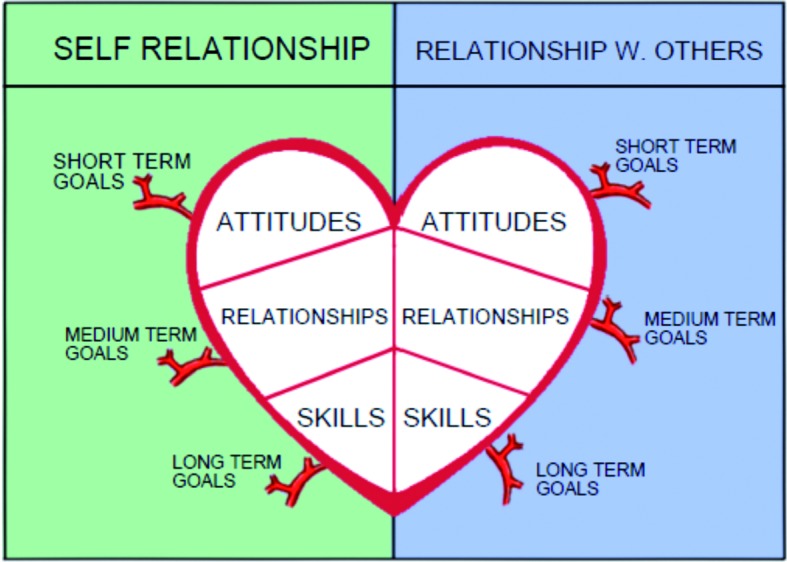

During this meeting, the personal assets will be determined, identified not only during the walking meditation but also during the whole project through the various exercises proposed and the experiences lived in everyday life. These internal assets will be tracked in what we will call “Mindful Map” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mindful Map

A heart-shaped illustration divided vertically into two quadrants or “petals” of the heart. A petal refers to the self relationship and the other petal refers to the relationship with others. Each petal of the heart in turn is divided into three other quadrants or shelters. These three shelters indicate the new attitudes, skills and relationships developed during the project. At the same time, the “Mindful Map” indicates the new objectives, interests, in the short, medium and long term, emerged during the project. These goals are reflected in the arteries or natural branches that leave the heart.

PHASE 4: Visibility

This phase will be centered on the diffusion and visibility of the effects that emerged from the whole project. This role will be played by the PG with the help of the CG.

We will use paper material with the maps of external and internal assets, distributed to associations, institutions, shared through the municipal council website, on local radios, in the local press, in posters, and electronic advertising.

We will also create online contents (e-Health site) not only to increase the visibility of the project, but also to continue to support, in an interactive way, the working group. It is assumed that CG and PG will continue to perform Mindfulness exercises regularly.

PHASE 5: Strengthening the relationships between the different parts of the community

According to the results of the mapping process, the interventions needed will be prioritized and modified according to their potential.

The map of assets created during the project will allow the health care context to choose strategies that centralize the local strengths, in order to address health issues appropriately, to define new actions in health policies and to favor a service orientation towards the promotion of health.

In addition, an informal sharing session will be organized to qualitatively evaluate the experience of the participants. Finally a final report will be drawn up on the health of this community, which will be delivered to local policy makers.

Also in this phase Samatha and Vipassana exercises will be practiced and specific exercises related to breathing will be added with the aim of generating greater mental calm, thus facilitating mental clarity, encouraging creativity and improving decision making, not neglecting, not even at this stage, self-care exercises. Finally, in this phase the CG will be asked to fill the same questionnaires filled in Phase 2, Moment 1.

Results analysis

Once the project is finished, a quantitative and qualitative assessment will be carried out using structure, process, outcomes and quality indicators. In particular:

1) Structure: every material and organizational element necessary to guarantee the correct execution of the project (human, physical, technical and financial organizational resources);

2) Process: procedures, activities, methods and organization suitable for the development of the project, best number of participants and activities that should be fulfilled;

3) General and specific aims that have been achieved;

3) The pre-post scores in the questionnaires administered to caregivers: SOC, Zarit, Burden and the Quality of Life.

4) The assessment of technical and organizational quality, as: effectiveness and efficiency (objective evaluation), acceptability and satisfaction of the assisted persons (subjective evaluation).

Conclusions

The project presented here is an innovative model to be implemented in health policies in the context of primary care.

The main objective of this project is not to identify the internal assets only during the mapping party, but throughout the entire project.

We are aware that Mindfulness has its limitations: it is an excellent tool to manage a multitude of stressful situations, but it is not a tool that by itself can solve psychopathological problems or symptoms already in progress. On the other hand, being able to be aware of the present moment by moment, is an important challenge in the current Western cultural approach, and represents a great space for growth. As Jon Kabat-Zinn states: “put awareness into your life and the changes will come by themselves” (2).

Given the lack of homogeneity in the management of health issues, the ABCD methodology with a salutogenic orientation reinforces and emphasizes the development of policies and activities based on the skills, abilities and resources of the less favored people and territories (11). It is an opportunity to promote active citizen participation and cooperation to achieve a sufficient level of empowerment to reduce these inequalities, thus maintaining an adequate level of health not completely influenced by social determinants.

Working with caregivers, with such a powerful tool as Mindfulness, is an opportunity that should not be left aside because of the idiosyncrasy of Mindfulness itself. The cross axis of this philosophy of life revolves around an indispensable pivot: remember people to take care of themselves, even when they are taking care of others.

References

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabat-Zinn J. Vivir con plenitud las crisis. como utilizar la sabiduría del cuerpo y de la mente para afrontar el estrés, el dolor y la enfermedad. [Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness] Barcelona: Ed. Kairós; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin L, He G, Yan J, Gu C, Xie J. The Effects of a Modified Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program for Nurses: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Workplace Health Saf. 2018:2165079918801633. doi: 10.1177/2165079918801633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol (New York) 2004;11:230–241. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel DJ. The mindful brain. New York: Ed. Norton & company; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Ed. Jossey-Bass; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindström B, Eriksson M. Guia del Autoestopista Salutogénico. Camino salutogénico hacia la promoción de la salud. [The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Salutogenesis: Salutogenic Pathways to Health Promotion] [Internet]. Documenta Universitaria, 2011. [Cited 2018 sett 30]. Available from: http://edu-library.com/es/show_oberts?id=410 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan A, Ziglio E. Hernán M, Morgan A, Mena AL, editors. Revitalizar la base de evidencias para la salud pública: un modelo basado en los activos. [Revitalizing evidence basis for public health: a model based on the assets] Formación en salutogénesis y activos en salud [Training on salutogenesis and health assets] Granada: Ed: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botello B, Palacio S, García M, Margolles M, Fernández F, Hernán M. Metodología para el mapeo de activos de salud en una comunidad [Methodology for mapping health assets in a community] Gac Sanit. 2013;27(2):180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kretzmann JP, McKnight JL. Introduction to Building Communities from the inside out: a path towards finding and mobilising a community’s assets. [Internet]. [Cited 2018 sett 3]. Available from: http://www.abcdinstitute.org/docs/abcd/GreenBookIntro.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segura del Pozo J. El enfoque ABCD de desarrollo comunitario. [The ABCD approach to community development] [Internet].[Cited 2018 sett 7]. Available from: http://www.ma.drimasd.org/blogs/salud_publica/2011/01/03/132305 . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pudelewicz A, Talarska D, Bączyk G. Burden of caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1111/scs.12626. doi: 10.1111/scs.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coppalle R, Platel H, Groussard M. Helping caregivers of people with dementia: a need to renew theoretical frameworks in France. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2018 doi: 10.1684/pnv.2018.0763. doi: 10.1684/pnv.2018.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hernán García M. Mapas de Activos y Desarrollo comunitario basado en activos.[ Asset Maps and Asset Based Community Development] Clase en el Seminario Avanzado de Promoción de la Salud. [Internet]. [cited 2018 ott 01]. Available from: http://www.gruse.es/pluginfile.php/113/mod_forum/attachment/532/GRUSE%20y%20activos_salud_F%20Exposito.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKnight J. Hernán M, Morgan A, Mena AL. El Mapeo de activos en la comunidad [Assets map in the community]. Formación en salutogénesis y activos en salud. [Training on salutogenesis and health assets] Granada: Ed: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKnight J, Kretzmann J. Mapping Community Capacity [Internet]. Institute for Policy Research. Northwestern University; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anaya Cintas F, Camacho, Alpuente A. Marcadelli S, Obbia P, Prandi C. Salutogenesi e promozione della salute. [Salutogenesis and health promotion] Assistenza domiciliare e cure primarie: Il nuovo orizzonte della professione infermieristica. [Domiciliary and primary care: a new horizion in nursing profession]. Milano: Ed. EDRA; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Community Toll Box. Identifying Community Assets and Resources. Kansas University Work Group on Health Promotion and Community Development. University of Kansas. [Internet].[Cited 2018 sett 09]. Available from: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/identify-community-assets/main . [Google Scholar]

- 19. Camacho Alpuente A. Meditaciones.[Meditations] [Audio]. [Internet]. [Cited 2018 oct 09]. http://mindfoodness.es/meditaciones/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci and Med. 1993;36(6):725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandri A, Anaya F. Adattamento al contesto italiano della scala di Zarit. Intervista di sovraccarico del caregiver [Adjustment to the Italian context of the Zarit Scale. Interview for caregiver’s burden] Obiettivo. 2004;2:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery RJV. Using and Interpreting the Montgomery Borgatta Caregiver Burden Scale. [Internet]. [Cited 2018 sep 29]. Available from: http://www4.uwm.edu/hbssw/PDF/Burden%20Scale.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuentelsaz Gallego C. Cuestionario de Calidad de Vida de los Cuidadores Informales [Questionnaire on the quality of Life of informal caregivers] J Advan Nursing. 2001;33:548–554. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neff KD. Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baer R, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Smith GT, Toney L. Using self-report assessments methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]