Abstract

Fractures of the acetabulum are rare in the pediatric age and may be complicated by the premature closure of the triradiate cartilage. We report a case of triradiate cartilage displaced fracture treated surgically. A 14 years old boy, following a high-energy road trauma, presented an hematoma in the right gluteal region with severe pain. According to radiographic Judet’s projections was highlighted a diastasis of the right acetabular triradiate cartilage. CT scan study with 2D-3D reconstructions confirmed as type 1 Salter-Harris epiphyseal fracture. Due to the huge diastasis of the triradiate cartilage, the patient was operated after 72 hours through a plating osteosynthesis. We decided during the preoperative study that the plates should not be removed. Two years after surgery, the patient is clinically asymptomatic; the radiographic evaluation shows a complete cartilage’s fusion and the right acetabulum is perfectly symmetrical to the contralateral. For the treatment of acetabular fractures in pediatric age should be carefully evaluated fracture’s pattern, patient’s age, skeletal maturity’s grade, acetabulum’s volume and diameter. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: acetabulum, triradiate cartilage, fracture, pediatric, surgery

Background

Fractures of the acetabulum are rare in the pediatric age and may be complicated by the premature closure of the triradiate cartilage hesitating in secondary acetabular dysplasia.

These injuries are mainly caused by high-energy trauma despite the energy required to fracture the strong and elastic pelvis in children is significant (1).

Among pediatric patients with pelvic trauma, the 1-15% have an acetabular fracture. Even fewer patients has a specific damage to the triradiate cartilage and the incidence of premature closure is less than 5% (0-11%) (2).

Due to the low frequency of these injuries, at this time, specified protocols of treatment were still not defined.

In literature both treatments, surgical and conservative, are supported with the common aim of restoring the anatomy without causing further damage to the triradiate cartilage’s blood supply, hoping to avoid symptomatic and dysplastic hip (3).

For these reasons, in the pediatric age, the early diagnosis and the choice of treatment of an acetabular fracture may be difficult.

We report a case of fracture of the triradiate cartilage we treated surgically.

Case presentation

A 14 years old boy, following a high-energy road trauma, arrived in the Emergency Room with pain in the right gluteal and inguinal region hightened by hip joint mobilization’s maneuvers. An evident hematoma was associated in the gluteal region. No other anatomic region was involved.

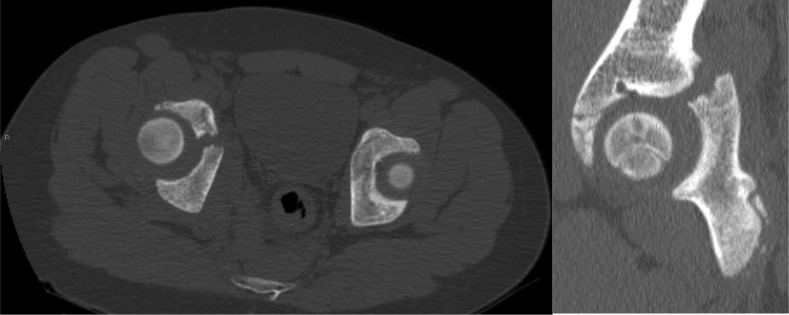

The radiographic study, according to Judet’s views, showed a right triradiate cartilage’s diastasis (Figure 1), later confirmed by CT scan performed in emergency.

Figure 1.

Outlet view: fracture-diastasis of the triradiate cartilage

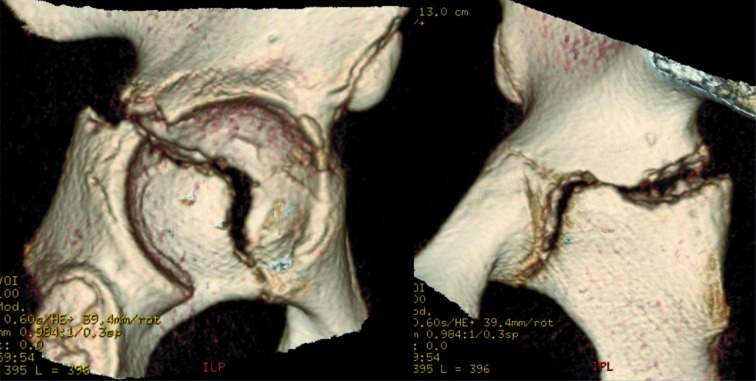

The lesion was evaluated with 2D-3D reconstructions and confirmed as Salter-Harris epiphyseal fracture-separation of ileum-ischium and ischium-pubis flanges of the triradiate cartilage (Figures 2a-b; 3a-b).

Figure 2a, b.

2 D CT reconstructions of the femoral head and quadrilateral surface

Figure 3a, b.

3 D CT reconstructions of the quadrilateral surface removing femoral head

Furthermore radiographic study of the pelvis showed us an advanced ossification valuable as Risser sign of a grade III (4).

Due to the huge diastasis of the triradiate cartilage and skeletal age, the patient was operated after 72 hours through ORIF with plate and screws.

The patient was positioned prone on the operating table with flexed knee 90°.

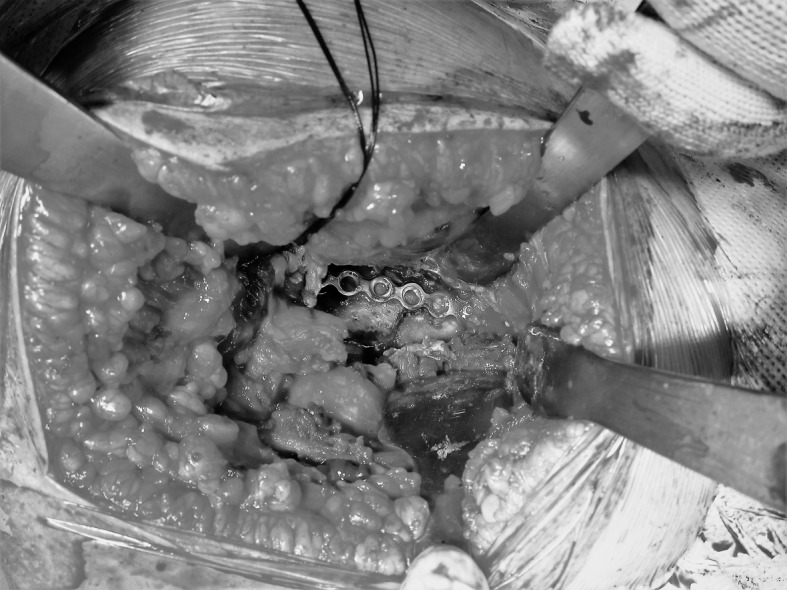

A Kocher-Langenbeck approach (5) was performed and the posterior column was exposed after aspiration of the fracture’s hematoma.

Fracture was reduced using dedicated retractors and levers avoiding further damage to ileo-ischiatic and ischio-pubic cartilage’s flanges.

Using C-arm with AP, Obturator and Iliac view the osteosynthesis with annealed steel Matta Plate (8 holes) and 4 screws, was performed.

Piriformis and external rotators tendons were reinserted, a drainage was placed suturing soft tissues. Postop X-ray control in Judet’s view was carried out (Figure 4a-b-c).

Figure 4.

Osteosynthesis with Matta Plates: antero-posterior (a), obturator (b) and iliac (c) view

The patient remained in bed-rest 45 days postop. Two weeks after surgery, he began hip passive mobilization and chair sitting; ten days later he got the active mobilization of the lower limbs.

45 days after surgery radiographic controls showed an epiphysiodesis bridge between ileum, ischium and pubis while respecting the coxofemoral anatomical relationship.

Therefore the patient started deambulation with 2 antibrachial crutches.

One month later he was walking freely without limping and pain.

He could come back to sport’s activity six months after surgery.

2 years later, the complete closure of the triradiate cartilage was displayed by a radiographic control (Figure 5a-b). The growth of the right acetabulum appeared well proportioned. The measurements of both acetabulum demonstrated a symmetrical development (Figure 5c-d).

Figure 5.

At 2 years complete healing of the right acetabulum in oblique views: obturator (a) and iliac (b). Symmetrical growth measuring the diameter (c) and the circumference (d) of both acetabulum

No radiographic signs of hip dysplasia was appreciated (shallow acetabulum, hip joint lateralization, femoral neck antiversion) as well as no signs of femoral head’s osteonecrosis.

The patient recovered a total hip range of motion (Figure 6) and came back to normal daily activities.

Figure 6.

At 2 years complete active range of motion: flexion and abduction

Discussion

The damage of the triradiate cartilage, caused by high-energy trauma, can lead to premature fusion with the formation of a bony bridge. If the acetabular cartilage remains entire and the triradiate closed, the growth will be not proportionate and will lead to a thickened medial wall with secondary lateralization of the hip joint.

The acetabulum becomes shallow deep whereby the femoral head will tend to subluxation.

The femoral neck antiversion will increase to avoid/reduce this dislocation.

Multiple events of subluxation could lead during the time to the cephalic osteonecrosis (2-6-7-8).

Clinically, patients may be asymptomatic even for a maximum of two following decades after trauma. As initial clinical signs may occur reduced range of motion, Trendelenburg positive sign and pain mobilization (8).

Radiographs can show the lateralization of the hip joint, an excessive femoral antiversion, a high acetabular index, up to joint degeneration’s signs (osteophytes, geodes, reducing joint space), osteonecrosis of the femoral head and other anomalies (2-8-9).

Treatment options are surgical and non-surgical. A lot of authors agree that the age at the time of the trauma, the breakdown of the fracture and the congruence of the articular surface are elements that influence the functional result of the patient. Few other authors stressed specific guidelines for surgical or nonsurgical treatment (3).

The majority of authors propose conservative treatment with bed rest and skeletal traction for 4-8 weeks (8).

Recently, the ORIF of unstable fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum was advocated even in childhood to restore symmetry, periarticular pelvic anatomy and function. This type of treatment has been shown to be associated with favorable clinical results with a low incidence of perioperative complications (10-11).

Bucholz et al. (7) suggested as an indication for surgical treatment, displaced fracture’s fragments (entity not well defined), patient’s age and fracture’s pattern.

Heeg et al. (12) recommended the surgical treatment in case of central fracture-dislocation, irreducible medial subluxation, intra-articular fragments, dislocated and exposed fractures and/or with posterior instability (12-13).

Brooks and Rosman (9) suggested ORIF when the central dislocation fracture is associated with central fragments.

The case presented in this study is one of the few cases in literature of epiphyseal acetabular fracture treated surgically.

The choice of surgical treatment was due after a careful radiographic study of the pelvis in AP obturator and iliac view and CT-scan 2D-3D reconstructions.

The main injury’s features were:

- a type I epiphyseal Salter-Harris fracture occurred trough the ischial-ileum flange and the ilium-pubic triradiate cartilage with a diastasis more than 2 mm enlarged

- an obvious deformity of the acetabular articular surface

- joint incongruence higher than 50% in a patient in teenage period (Risser III).

Then we decided for the surgical treatment.

In our case, considering patient’s age, acetabulum’s volume and diameter, skeletal maturity’s grade, we evaluated the expectation of acetabulum’s remaining growth during adolescence until adulthood (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurement (arithmetic mean) of the acetabular’s diameters and circumferences (100 cases for each age group)

| Age | Acetabular diameter (in mm) | Acetabular circumference (in mm) |

| 10 | 43,7 | 137,1 |

| 12 | 48,9 | 153,5 |

| 14 | 49,3 | 154,9 |

| 16 | 50,1 | 157,2 |

| 20 | 53 | 166,4 |

| CM (16yo) | 49,9 | 156,7 |

This study shows that the volumetric enhancement of the acetabulum is expected to be small.

The aspect that we considered most important was to prevent the acetabulum become shallow deep avoiding a development of excessive femoral neck antiversion.

After the acetabulum enhancement’s estimation (Table 1), we calculated that the deepening expected since the trauma to adulthood, would be less than 2 mm.

For this reason, surgical reduction was conducted creating an epiphysiodesis that could facilitate the achievement of size and volume of an adult acetabulum.

Accepting a reduction with a little diastasis between the growing flanges of the triradiate cartilage, any compression causing an early closure of the cartilage was avoided (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Reduction with a little diastasis between the growing flanges of the triradiate cartilage and osteosynthesis with annealed steel Matta Plate (8 holes)

Two years after surgery the growth of the right acetabulum seems to be regular.

The measurements on both acetabulums allow to appreciate a perfectly symmetrical eumorphisms (volumes and diameters) (Figure 5c-d).

At this time, the patient 16 years old is asymptomatic without radiographic signs of hip dysplasia.

Because estimated acetabulum enhancement from now to adulthood is minimal (Table 1), because of Risser IV sign, because of triradiate cartilage of both hip appeared fused (Figure 5c-d) don’t bring out indications that justify the removal of plate and screws by an additional surgical approach that would be invasive and not without risks.

Nevertheless it would be essential to follow the patient over time until the adulthood.

Conclusion

During the pediatric age the choice of epiphyseal hip fracture’s treatment is still controversial.

Fracture’s pattern, patient’s age, skeletal maturity’s grade, acetabulum’s volume and diameter should be carefully evaluated.

When the surgical treatment is chosen, an additional surgical time to remove fixation devices in adolescence may not be strictly necessary.

Conflict of interest:

None to declare

References

- 1.Smith WR, Oakley M, Morgan SJ. Pediatric pelvic fractures. J Pediatr Othop. 2004;24:130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scuderi G, Bronson MJ. Triradiate cartilage injury: report of the two cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop. 1987;217:179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liporace FA, Ong B, Mohaideen A. Development and Injury of the Triradiate Cartilage with its effects on acetabular Development: Review of the Literature. J Trauma. 2003;54:1245–1249. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000029212.19179.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risser JC. The Iliac apophysis: an invaluable sign in the management of scoliosis. Clin Orthop. 1958;11:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mudd CD, Boudreau JA, Moed BR. A prospective randomized comparison of two skin closure techniques in acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014 Sep;15(3):189–94. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0282-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponseti IV. Growth and development of the acetabulum in the normal child: anatomical, histological, and roentgenographic studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:575–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucholz RW, Ezaki M, Ogden JA. Injury to the acetabular triradiate physeal cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:600–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trousdale RT, Ganz R. Posttraumatic acetabular dysplasia. Clin Orthop. 1994;305:124–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks E, Rosman M. Central fracture-dislocation of the hip in a child. J Trauma. 1988;28:1590–92. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karunakar MA, Goulet JA, Mueller KL, et al. Operative treatment of unstable pediatric pelvis and acetabular fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:34–8. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magu NK, Gogna P, Singh A, Singla R, Rohilla R, Batra A, Mukhopadhyay R. Long term results after surgical management of posterior wall acetabular fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2014 Sep;15(3):173–9. doi: 10.1007/s10195-014-0297-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heeg M, de Ridder VA, Tornetta P III. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop. 2000;376:80–86. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heeg M, Visser JD, Oostvogel HJM. Injuries of the acetabular triradiate cartilage and sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:34–37. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B1.3339056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]