Abstract

Transdermal therapeutic systems (TTS) have become a popular method of drug delivery because they allow drugs to be delivered in a rate-controlled manner, avoiding first-pass metabolism and the fluctuating plasma concentrations encountered with oral medications. Unfortunately, TTS may provoke adverse skin reactions as irritating contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis: TTS seem to be ideally suited to produce sensitization because they cause occlusion, irritation, due to the repeated placement of the allergen in the same skin location. Since TTS consist of an adhesive, an active pharmaceutical drug and enhancing agents, sensitization may develop owing to one of these three agents. The purpose of this manuscript is to review known responsible allergens of contact dermatitis due to TTS. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: allergic contact dermatitis, drugs, excipients, rubber, transdermal therapeutic systems

Introduction

Transdermal absorption of pharmacological active ingredients has been carefully studied in the last 40 years as the skin, being the most extended and most easily accessible organ of the body, represents an attractive alternative to oral administration. Transdermal administration is of easy execution, compared to the intramuscular or intravenous methods, and it assures a constant absorption of the drug during the day, which is preferibile to the pulsed bioavailability caused by oral adminstration. Moreover, transdermal administration often succeeds in obviating the annoying and badly tolerated gastrointestinal side effects, typical of oral admnistration.

Beginning from the introduction of the first transdermal patch made of scopolamine, in 1979, successively numerous transdermal systems were created using several active principles. Currently, the most used ones are made of scopolamine, estrogens, nitroglycerin and clonidine. The drug, in order to be absorbed through the skin, must possess such properties to cross the corneous layer. The permeation of the active principle through the corneous layer is, in fact, the limiting phase of such modality of administration, since it consists of the processes of partitioning and diffusion through the lipophilic and then hydrophilic phase of the superficial layers of the epidemis, which are opposed to the last passage of diffusion in the capillary net of the derma. A candidate drug for transdermal transport must therefore possess both lipophilic and hydrophilic characteristics, so that the moderated hydrophilicity does not prevent the partition through the lipid-rich corneous layer, and the moderated lipophilicity does not obstacle the diffusion in the lower watery layers of the epidermis and beyond. In order to estimate the partitioning of a compound through the skin, the coefficient of division in octanol/water is used (1).

The application of transdermal patches is not free from disadvantages. In fact, irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) provoked by the adhesive, the active principle or the excipients may often appear, and also allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), consequent to sensitization to the administered active principles.

Methods

The literature was searched via the Medline/PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/pubmed) combining transdermal therapeutic systems and transdermal patches with contact dermatitis and skin reaction.

Allergic contact dermatitis and TTS

ACD is a type IV cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that usually presents with lesions that can vary from erythema and papules to vesicles and bullae. ACD to TTS can be caused by all the components of TTS that are an active drug, an adhesive and excipients; moreover, different kinds of TTS are currently available. Among these, the most common are matrix TTS that are characterized by a single-layer adhesive, active drug and other components that get in contact with the skin. Other kinds of TTS are local-action transcutaneous TTS and reservoir TTS: the former is similar to matrix TTS, except for a non-woven polyester backing that supports the active drug; the latter is characterized by a rate-controlling membrane that releases the active drug contained in a depot. Nowadays, ACD to TTS can be considered rare; conversely, irritant reactions are more common. Patients should follow simple recommendations to avoid these latter: TTS should be applied daily by rotating the application site and should be removed carefully; moisturizers and gentle cleansings are recommended, topical corticosteroids should be used only if necessary (2, 3). Irritant contact dermatitis to TTS may present with skin lesions similar to ACD ones (table 1). For this reason, patch testing is required in all cases of skin reaction onset after application of TTS.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICD and ACD from TTS (modified from (2))

| ICD | ACD | |

| Morphology | Erythematous-papular/vesicular/bullous lesions sharply circumscribed to the area of contact. | Erythematous-papular/vesicular/bullous lesions (vesiculation is more typical) circumscribed to the area of contact but with ill-defined limits. Dissemination of the lesions can occur |

| Symptoms | Burning, stinging, itching | Burning, stinging, itching |

| Resolution | Characterized by decrescendo phenomenon following patch removal; typically within 48 h | Characterized by crescendo phenomenon. Resolution is slower than ICD |

| Clinical diagnosis | On the basis of lesions and clinical course | Patch testing with the individual components of the TTS |

ACD to TTS

Nitroglycerin

The use of transdermal patches made of nitroglycerin represents a common antianginous treatment. In literature, numerous cases of ACD to transdermal patches made of nitroglycerin are reported (4-8). Kounis et al. (9) have demonstrated that the reactions to such patches are mostly irritative and only minimally allergic. In the suspicion of ACD to patches made of nitroglycerin, it is indispensable to carry out a patch test with the active principle in order to define the type of reaction (9).

Scopolamine

Scopolamine, also known as hyoscine, is used for the prevention of the symptomatology of motion sickness, generally in the form of transdermal patches to be applied for 72 hours behind the ear. Numerous cases of ACD due to such patches are reported in literature (10-12). Gordon et al. have evidenced that 10% of the crew of a ship, formed by 164 people, all using transdermal patches with scopolamine, showed eczematous reactions in the application area of the support (13). These patients, who underwent a patch test with the same transdermal patch, without the active principle, did not show any positivity, suggesting that scopolamine was responsible for the allergic reaction.

Nicotine

Transdermal patches made of nicotine are used as an aid to the interruption of the smoking habit. Although nicotine is a weak sensitizer, when transmitted through transdermal patches, it can provoke ACD (14-18).

Testosterone

Transdermal devices made of testosterone are used in clinical practice for the treatment of dysfunctional pathologies, correlated to the deficit of the hormone. Very rarely, also this drug can provoke ACD cases (19-21). However, the prevailing cutaneous reactions to such patches turn out to be irritative (17).

Estradiol

Commonly used for treating the symptoms of menopause, transdermal patches made of estradiol have been reported as a cause of sensitization towards such hormone (22-26). Moreover, Lamb and Wilkinson have assumed that the sensitization to topically applied estradiol can represent a risk factor for the development of ACD to corticosteroids (23). However, patients sensitized to estradiol seem to be able to take the same active principle orally, without the appearance of any cutaneous reactions.

Clonidine

Clonidine, a drug usually taken orally for the treatment of hypertension, can be successfully transmitted through transdermal patches kept in the area for a period of application of 7 days, which is a longer period, compared to the other active principles. Even if clonidine does not seem to possess a high sensitizing capability, probably due to the long period of application, the ACD for such drug is rather frequent (27-29). Maibach et al. (30) have pointed out the role of transdermal administration in causing allergic sensitization by comparing a group of 103 patients, who underwent a topical application of clonidine 9% in vaseline, with a group of 92 patients, who underwent the application of transdermal patches with clonidine. The results showed that after 3 weeks 4.3% of patients belonging to the 2nd group turned out sensitized to clonidine, while no case of sensitization was found among the patients in the 1st group.

Rotigotine

Rotigotine is a drug used for the treatment of the first stage of Parkinson’s disease. The treatment includes the application of a patch containing 2 mg of the active principle every 24 hours, paying attention to reapply it each time in a different place. Among the most common side effects, there are nausea, sleepiness, dyspepsia and asthenia. Adverse cutaneous reactions are considered rare; however, during the last few years two cases of ACD due to transdermal patches containing rotigotine were reported in literature (31, 32).

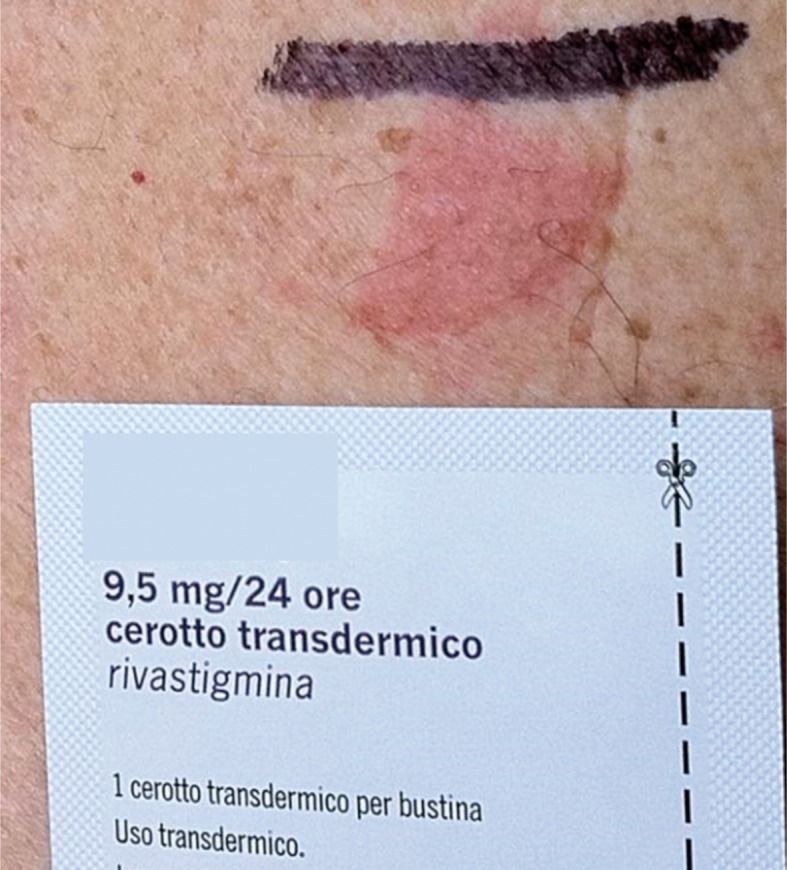

Rivastigmine

Rivastigmine is a cholinesterase inhibitor, used to improve cognitive functions in dementia forms of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Rivastigmine has been commercialized since 2007 also as a transdermal patch, in order to eliminate the gastrointestinal side effects of oral administration (vomiting, nausea and diarrhea). Recently, some cases of adverse reactions to transdermal patches made of rivastigmine were reported (33-35) (Fig. 1). Moreover, Makriset et al. (35)have studied the usefulness of the desensitizing therapy in a patient with Alzheimer’s dementia, who had developed ACD to the rivastigmine contained in the transdermal patch used for the therapy. In this case it was possible to demonstrate how, once an adequate desensitizing therapy was carried out, it was possible to administrate rivastigmine orally once again to patients previously sensitized because of the contact with the same active principle contained in transdermal patches.

Figure 1.

Positive patch test to a transdermal therapeutic system containing rivastigmine

Adhesives and excipients

ACD to transdermal patches, besides the active principles and excipients they contain, can also be caused by the adhesive substances that guarantee the adhesion of the support to the skin: rosin, rosin esters and silicone derivatives. In case of ACD to medicated patches, it is important, therefore, to carry out a patch test with a placebo patch, that is, a support identical to that constituting the transdermal system, devoid of the active principle, in order to verify the eligibility of the support in the determination of the reaction (9, 10, 36, 37).

Among the excipients responsible for ACD to patches, menthol is reported (Fig. 2, 3). An active principle contained in mint oil, it is a strongly aromatic, bitter compound, known for its anti-inflammatory, analgesic and vasodilatory effects. In the light of its properties, it is used in transdermal systems in order to facilitate the penetration of the active principle they contain. Menthol is a weak sensitizing agent and only very rarely it provokes ACD. However, cases of allergies due to contact with menthol can likely occur as a consequence of the metabolization of the menthol in mentone, a more powerful sensitizing agent. In literature, cases of ACD provoked by the use of cigarettes, tooth-pastes and scents made of menthol are reported (38), and also subsequent to the use of patches containing menthol as an excipient (39).

Figure 2.

Allergic contact dermatitis to a transdermal therapeutic system with flurbiprofen for lumbar pain. The culprit allergen was menthol, an excipient used to facilitate the penetration of the active drug

Figure 3.

Positive patch test to a transdermal therapeutic system caused by an excipient (menthol)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the majority of skin reactions to TTS are irritant reactions that self-heal once the exposure to the patch is avoided. On the basis of the reports on sensitization to TTS, there is sufficient evidence to confirm that such therapeutic systems can also cause ACD, being an ideal environment to elicit contact allergy. Skin reactions are usually mildly characterized by erythematous-vesicular lesions that heal in a few days, once exposure to patches is avoided, thanks to topical therapy with corticosteroids. Rarely, systemic skin reactions can be observed. Patients should be educated to properly use them and immediately seek evaluation by dermatologists in case of suspected skin reactions. ACD to TTS can be caused by drugs, or excipients and adhesives. Patch tests should be therefore performed with the same TTS, with active principles and with excipients, to perform a correct differential diagnosis versus irritant ICD. Further studies in this area are required as TTS become more widespread among several diseases.

Conflict of interest:

None to declare

References

- 1.Subedi RK, Oh SY, Chun M-K, Choi H-K. Recent avances in transdermal drug delivery. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:339. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-0301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ale I, Lachapelle J, Maibach H. Skin tolerability associated with transdermal drug delivery systems: an overview. Adv Ther. 2009;26:920–35. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warshaw EM, Paller AS, Fowler JF, Zirwas MJ. Practical management of cutaneous reactions to the methylphenidate patch: recommendations from a Dermatology Expert Panel Consensus Meeting. Clin Ther. 2008;30:326–37. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Calderon R, Gonzalo-Garijo MA, Rodriguez-Nevado I. Generalized allergic contact dermatitis from nitroglycerin in a transdermal therapeutic system. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:303. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machet L, Martin L, Toledano C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from nitroglycerin contained in 2 transdermal systems. Dermatology. 1999;198:106. doi: 10.1159/000018082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres V, Lopes JC, Leite L. Allergic contact dermatitis from nitroglycerin and estradiol transdermal therapeutic systems. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld AS, White WB. Allergic contact dermatitis secondary to transdermal nitroglycerin. Am Heart J. 1984;108:1061. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topaz O, Abraham D. Severe allergic contact dermatitis secondary to nitroglycerin in a transdermal therapeutic system. Ann Allergy. 1987;59:365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kounis NG, Zavras GM, Papadaki PJ, et al. Allergic reactions to local glyceryl trinitrate administration. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher AA. Dermatitis due to transdermal therapeutic systems. Cutis. 1984;34:526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Willigen AH, Oranje AP, Stolz E, van Joost T. Delayed hypersensitivity to scopolamine in transdermal therapeutic systems. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:146. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trozak DJ. Delayed hypersensitivity to scopolamine delivered by a transdermal device. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:247. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon CR, Shupak A, Doweck I, Spitzer O. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by transdermal hyoscine. BMJ. 1989;298:1220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6682.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bircher AJ, Howald H, Rufli T. Adverse skin reactions to nicotine in a transdermal therapeutic system. Contact Dermatitis. 1991;25:230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1991.tb01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan WP. Clinical evaluation of contact sensitization potential of a transdermal nicotine system (Nicoderm) J Fam Pract. 1992;34:709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eichelberg D, Stolze P, Block M, Buchkremer G. Contact allergies induced by TTS treatment. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1989;11:223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincenzi C, Tosti A, Cirone M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from transdermal nicotine systems. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Färm G. Contact allergy to nicotine from a nicotine patch. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb03545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley DA, Wilkinson SM, Higgins EM. Contact allergy to a testosterone patch. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shouls J, Shum KW, Gadour M, Gawkrodger DJ. Contact allergy to testosterone in an androgen patch: control of symptoms by pre-application of topical corticosteroid. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:124. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.045002124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ta V, Chin WK, White AA. Allergic contact dermatitis to testosterone and estrogen in transdermal therapeutic systems. Dermatitis. 2014;25:279. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehncke WH, Gall H. Type IV hypersensitivity to topical estradiol in a patient tolerant to it orally. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmichael AJ, Foulds IS. Allergic contact dermatitis from oestradiol in oestrogen patches. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch P. Allergic contact dermatitis from estradiol and norethisterone acetate in a transdermal hormonal patch. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:112. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.44020914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panhans-Gross A, Gall H, Dziuk M, Peter RU. Contact dermatitis from estradiol in a transdermal therapeutic system. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43:368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb SR, Wilkinson SM. Contact allergy to progesterone and estradiol in a patient with multiple corticosteroid allergies. Dermatitis. 2004;15:78. doi: 10.2310/6620.2004.03033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corazza M, Mantovani L, Virgili A, Strumia R. Allergic contact dermatitis from a clonidine etransdermal delivery system. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groth H, Vetter H, Knuesel , Vetter W. Allergic skin reactions to transdermal clonidine. Lancet. 1983;2:850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horning JR, Zawada ET, Simmons JL, et al. Efficacy and safety of two-year therapy with transdermal clonidine for essential hypertension. Chest. 1998;93:941. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maibach H. Clonidine: irritant and allergic contact dermatitis assays. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bershow A, Warshaw E. Cutaneous reactions to transdermal therapeutic systems. Dermatitis. 2011;22:193–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raison-Peyron N, Guillot B. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by rotigotine in a transdermal therapeutic system. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:121–2. doi: 10.1111/cod.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makris M, Koulouris S, Koti I, Aggelides X, Kalogeromitros D. Maculopapular eruption to rivastigmine’s transdermal patch application and succesful oral desensitization. Allergy. 2010;65:925. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grieco T, Rossi M, Faina V, De Marco I, Pigatto P, Calvieri S. An atypical cutaneos reaction to rivastigmine transdermal patch. J Allergy (Cairo) 2011;2011:752098. doi: 10.1155/2011/752098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenspoon J, Herrmann N, Adam DN. Transdermal rivastigmine: management of cutaneous adverse events and review of the literature. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:575. doi: 10.2165/11592230-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McBurney EI, Noel SB, Collins JH. Contact dermatitis to transdermal estradiol system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:508. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dwyer CM, Forsyth A. Allergic contact dermatitis from methacrylates in a nicotine transdermal patch. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;30:309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ale SI, Hostynek JJ, Maibach HI. Menthol: a review of its sensitization potential. Exog Dermatol. 2002;1:74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foti C, Conserva A, Antelmi A, Lospalluti L, Angelini G. Contact dermatitis from peppermint and menthol in a local action transcutaneous patch. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:312. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2003.0251i.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]