Abstract

Background: Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), are chronic, relapsing-remitting diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn’s disease (CD), Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Unclassified IBD (IBDU). Their pathogenesis involves genes and environment as cofactors in inducing autoimmunity; particularly the interactions between enteric pathogens and immunity is being studied. Helicobacter pylori (HP) is common pathogen causing gastric inflammation. Studies found an inverse prevalence association between HP and IBD, suggesting a potential protecting role of HP from IBD. Methods: A literature search of the PubMed database was performed using the key words‘’helicobacter pylori’’,‘’inflammatory bowel disease’’,‘’crohn disease’’, “ulcerative colitis”. Embase, Medline (OvidSP), Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed publisher, Cochrane and Google Scholar were also searched. Prevalence rate-ratios among HP in IBD patients, HP in CD patients, HP in UC patients, HP in IBDU patients were extracted, each group was compared with controls, to verify the inverse association between HP and IBD prevalence. Results: In all groups the dispersion of data suggested an inverse association between IBD group and controls, even when the comparison was carried out separately between each group of newly diagnosed patients and controls, to rule out the possible bias of ongoing pharmacologic therapy. Conclusions: The results of this review show a striking inverse association between HP infection and the prevalence of IBD, independently from the type of IBD considered across distinct geographic regions. Anyway, data should be interpreted cautiously, as wider, prospective and more homogeneous research on this topic are awaited, which could open new scenarios about environmental etiology of IBD. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, infection, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, prevalence, association

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), are chronic, relapsing-remitting diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn’s disease (CD), Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Unclassified IBD (IBDU). Their pathogenesis is still not completely understood; several environmental, immune and host (e.g., genetic, epithelial, immune and non-immune) factors are involved. Complex interactions between the immune system, enteric commensal bacteria/pathogens and host genotype are thought to underlie the development of IBD (1). Many factors have been examined as markers of environmental exposures in early life, including family size, sibship, birth order, country of birth, urban upbringing, socioeconomic status, and pet exposure (2).

Helicobacter pylori (HP) is a gram-negative, spiral-shaped pathogenic bacterium responsible for chronic gastritis. That mucosal inflammatory process is most likely driven by a cellular immune response to the on-going stimulation of the host’s immune system caused by the bacterium. This results in high production of interleukin (IL)-12, leading to a T helper type 1 (Th1)-polarized response and elevated levels of Th-1 cytokines (3, 4). Products of the local immune reactions may travel to extra-gastric sites, thus linking HP infection to the pathophysiology of a variety of extra-gastric diseases, including autoimmune disorder (5). Interestingly, however, HP has been proposed to play a protective role against the development of certain autoimmune disorders such as asthma and type 1 diabetes mellitus (6). The mechanisms underlying this protective role of HP infection is thought to be differential expression of an acute and/or chronic local mucosal inflammatory response, which may elicit a systemic release of cytokines, which in turn may down-regulate systemic immune responses and suppress autoimmunity (7).

In IBD, dysregulation of the immune response of the host to commensal bacteria has been proposed as an important underlying pathogenetic mechanism. Increased attachment of gut bacteria to the intestinal epithelium has been documented in IBD. Moreover, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, an up-regulation of cell signaling molecules and a Th1-driven immune reaction are characteristics implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD, especially CD (8).

The similarities between the immunobiology of IBD and that of HP infection provide background for the hypothesis that HP infection may be involved in the modulation of the pathogenesis of IBD.

Such speculation has been investigated in various studies. According to epidemiology data, IBD are more prevalent in developed countries than in developing countries, whereas HP infection shows higher prevalence in developing countries than in developed ones (9). Case control studies suggest an inverse association between HP and IBD.

In this review we analyze and evaluate a large volume of published data with the aim to clarify the proposed association between HP infection and IBD.

Materials and Methods

In order to verify the association between HP infection and IBD, we selected the studies focused on the evaluation of the prevalence of HP in IBD and in otherwise healthy controls.

A literature search of the PubMed database was performed using the key words‘’helicobacter pylori’’,‘’inflammatory bowel disease’’,‘’crohn disease’’, “ulcerative colitis”. Embase, Medline (OvidSP), Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed publisher, Cochrane and Google Scholar were searched as well. Only English language publications were included.

Inclusion criteria among these papers were: case study papers, case report, clinical trial, retrospective study or journal article, published in the last 10 years, addressed to study the prevalence rate of Helicobacter pylori in IBD patients; in case the study did not include a control cohort, the prevalence was compared with a study about HP prevalence regarding otherwise healthy people in the same country in the same period (+/-5 years). Papers with topic not regarding the relationship between HP and IBD to obtain a prevalence rate, reviews of literature or meta-analyses were excluded. Two investigators (SK and FG) independently reviewed and extracted data from the papers according to the predetermined criteria. For each study the following data were extracted: year of the study, country, number of patients affected by IBD, number of patients affected by CD, number of patients affected by UC, number of patients affected by IBDU, number of controls, percentage of HP infection in IBD, CD UC, and IBDU affected patients. Details are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Prevalence rate-ratios between HP in IBD patients and in controls, between HP in CD patients and in controls, between HP in UC patients and in controls, HP in IBDU patients and in controls were compared to verify the existence of an inverse association between HP and IBD prevalence. Since the results of the prevalence of HP infection in IBD affected patients could be theoretically influenced by the more frequent treatments with antibiotics, sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants, we considered separately those studies dealing with newly diagnosed IBD patients (therefore not exposed to antibiotics, sulfasalazine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants) and compared the same HP prevalence rate-ratio (Table 2).

Table 1.

HP prevalence in IBD patients

| Author | Country | Year | % HP in IBD | % HP in CD | % HP in UC | % HP in IBDU | % HP in Controls |

| So H. et al (10) | Korea | 2016 | 23,4 | 23,4 | / | / | 52,5 |

| Magalhaes MH et al (11) | Brazil | 2014 | 57,9 | 54,5 | 62,5 | / | 50 |

| Zhang S. et al (12) | China | 2011 | 19,7 | 18,3 | 21,2 | / | 48,8 |

| Sonnenberg A. Genta R. (13) | USA | 2012 | 4,4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Rosania R. et al (14) | Germany | 2018 | 11 | 12 | 11 | / | 25 |

| Lahat A. et al (15) | Israel | 2017 | 10,7 | 10,7 | / | / | 39 |

| K.Farkas, H.Chan et al (16) | Hungary | 2016 | 13,9 | 13,9 | / | / | 14,6 |

| K.Farkas, H.Chan et al (16) | China | 2016 | 4 | 4 | / | / | 15 |

| Roka et al. (17) | Greece | 2014 | 3,8 | 4,5 | 5,8 | 1,7 | 13,2 |

| Annunziata et al (18) | Italy | 2012 | 8,4 | 8,4 | / | / | 39 |

| Ando T. et al (19) | Japan | 2008 | 8 | 8 | / | / | 42 |

| Ram M. et al (6) | Israel, Italy, Serbia | 2012 | 2,5 | / | / | / | 39 |

| Sonnenberg A et al (20) | USA | 2011 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| Danelius M. et al (21) | Sweden | 2009 | 10,8 | 5,8 | 9,5 | 25 | 44,4 |

| Song M.J. Et al (22) | Korea | 2009 | 25,3 | 17,7 | 32 | / | 52,5 |

| Hong C.H. et al (23) | Korea | 2009 | 32,5 | 27 | 37,2 | / | 53,2 |

| Sakuraba A. et al (24) | Japan | 2014 | 10,8 | 10,8 | / | 42 |

HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBD: stands for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases; CD: stands for Crohn’s Disease; UC: stands for Ulcerative Colitis; IBDU: stands for Unclassified Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Table 2.

HP prevalence in newly diagnosed IBD

| Author | Country | Year | % HP in IBD | % HP in CD | % HP in UC | % HP in IBDU | % HP in Controls |

| Park J.H. et al (25) | Korea | 2017 | 5,8 | 5,8 | / | / | 52,5 |

| Hansen R. et al (26) | UK | 2013 | 2,3 | 0 | 7,7 | 0 | 14,3 |

| Xiang Z. et al (27) | China | 2013 | 27,1 | 27,1 | / | / | 47,9 |

| Kaakoush et al (28) | Australia | 2011 | 18,2 | 18,2 | / | / | 10,8 |

| Jin X. et al (29) | China | 2013 | 30,5 | / | 30,5 | / | 57 |

| Horje et al (30) | The Netherlands | 2016 | 6,7 | 6 | 8 | / | 30 |

HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBD: stands for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases; CD: stands for Crohn’s Disease; UC: stands for Ulcerative Colitis; IBDU: stands for Unclassified Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The techniques used to assess the HP infection in the selected studies were not uniform. Twelve studies based the HP infection diagnosis on the histopathologic analysis of gastric biopsies, 3 articles on Urease Breath Test positivity, 2 on the results of cultural tests, 1 on the research of fecal HP antigens and 2 on the result of the titer of serum anti-HP IgG (which was considered positive only if superior to 30 Enzyme Immune Unit (EIU)).

Results

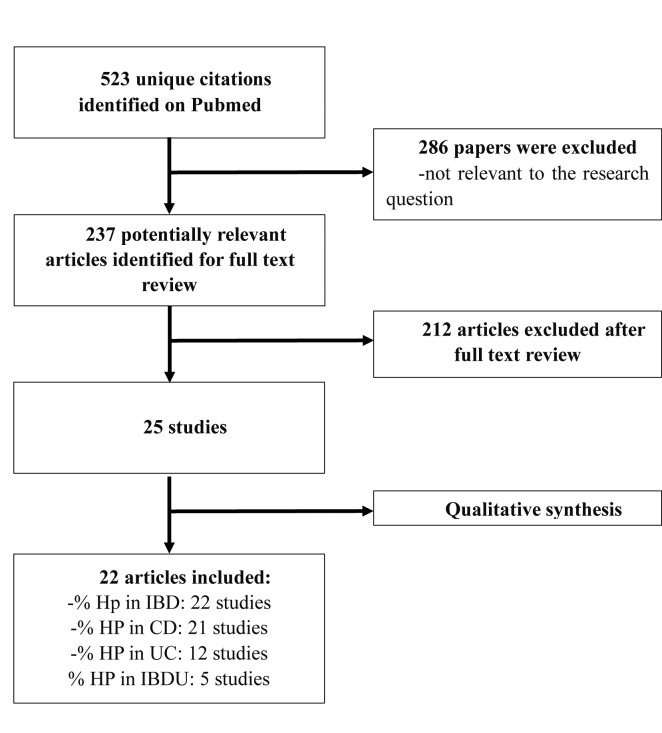

The literature search retrieved 523 papers, among whom 286 were excluded since not consistent with the aim of the present review. Full texts of 237 articles were reviewed to assess eligibility. After the assessment of eligibility, 22 articles about Helicobacter pylori infection and IBD and meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the selection of the included studies. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBD: stands for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases; CD: stands for Crohn’s Disease; UC: stands for Ulcerative Colitis; IBDU: stands for Unclassified Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The included studies report data from countries belonging to four different continents (China, Korea, Italy, Israel, USA, Germany, Hungary, Brazil, United Kingdom, Greece, Australia, The Netherlands, Japan and Sweden). There was considerable variability in the prevalence rates of HP infection both in IBD affected patients and in controls among the study populations. Prevalence rates of HP infection in IBD patients were the lowest in UK (2,3%) and the highest in Brazil (57.9%). Similarly, the highest prevalence rates for HP infection in controls were reported in Brazil and Korea (50 and 52,5% respectively), the lowest in USA (7%) as shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

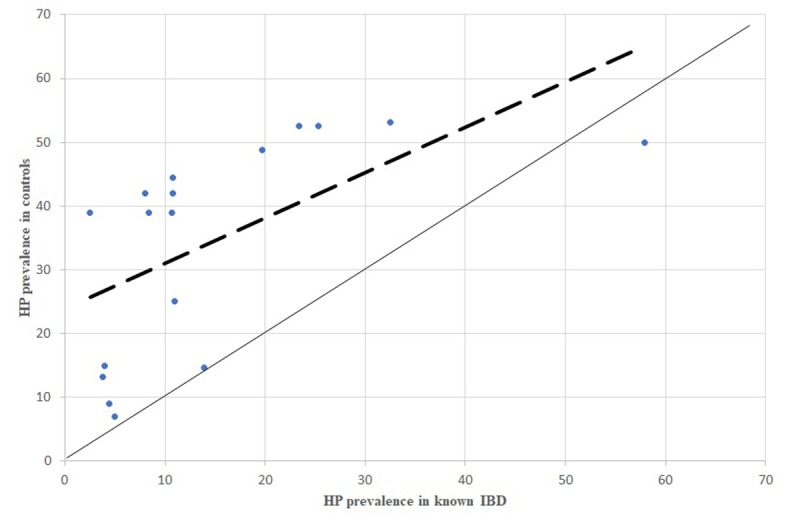

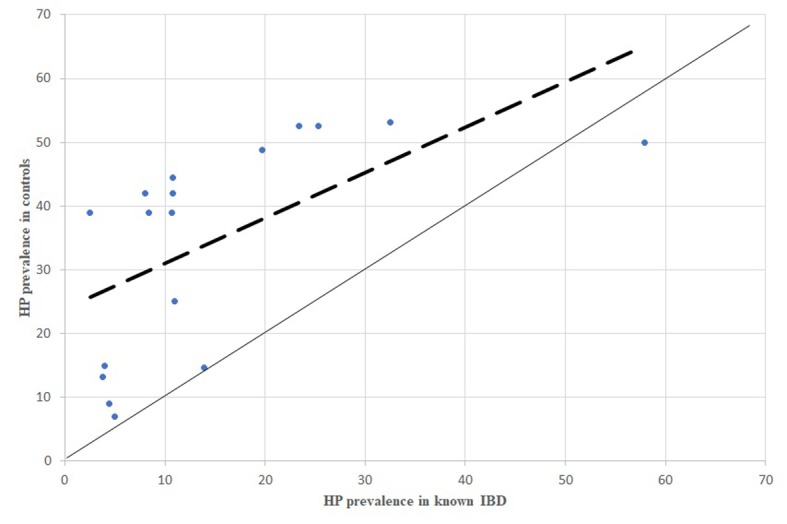

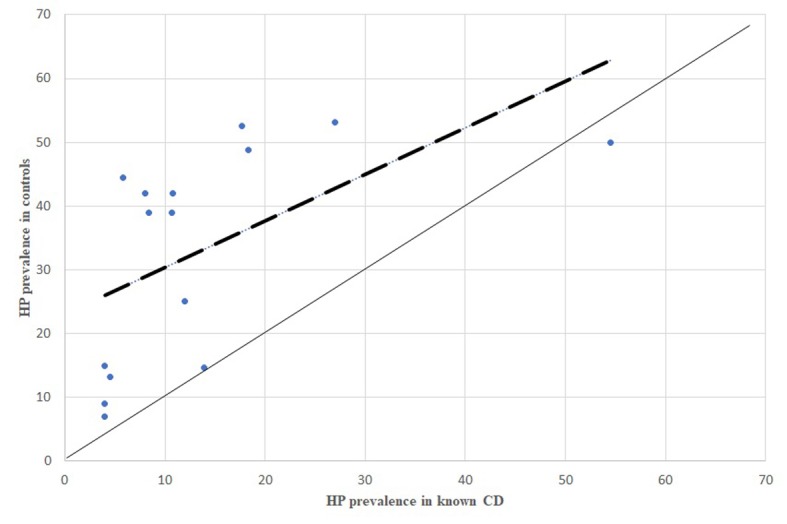

Overall, the difference in prevalence of HP infection between IBD affected patients and controls was significative in 16/22 studies. As shown in Figure 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, which were obtained by a comparison between the HP prevalence in IBD and controls in all the studies, the dispersion of data demonstrated higher prevalence in controls. This suggests the existence of an important inverse association between HP infection and IBD (both in CD and UC, and even in IBDU).

Figure 2.

HP prevalence in newly diagnosed IBD patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBD: stands for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Figure 3.

HP prevalence in known IBD patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBD: stands for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Figure 4.

HP prevalence in known CD patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; CD: stands for Crohn’s Disease

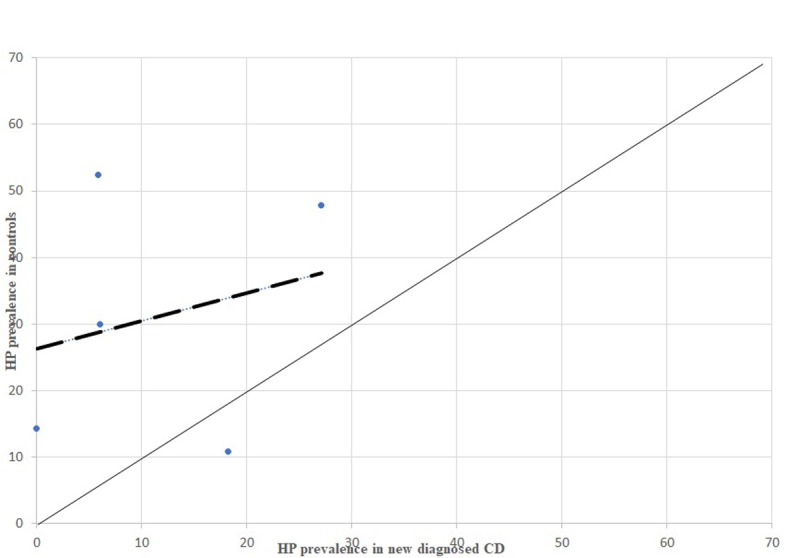

Figure 5.

HP prevalence in newly diagnosed CD patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; CD: stands for Crohn’s Disease

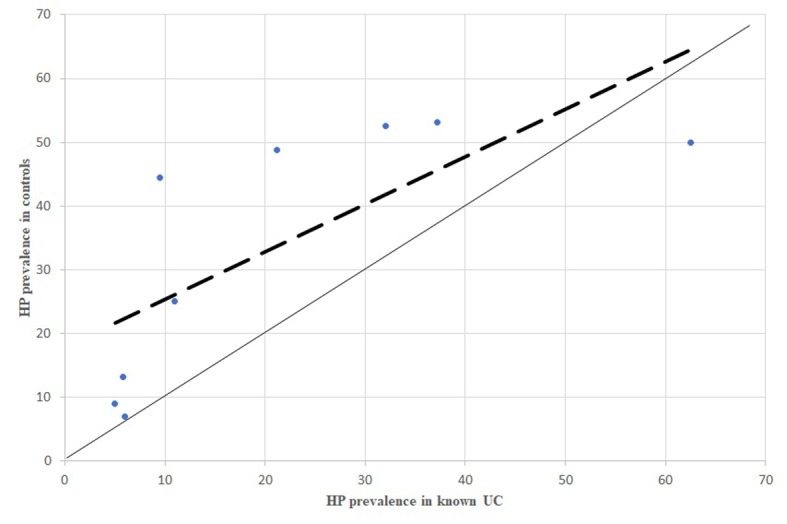

Figure 6.

P prevalence in known UC patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; UC: stands for Ulcerative Colitis

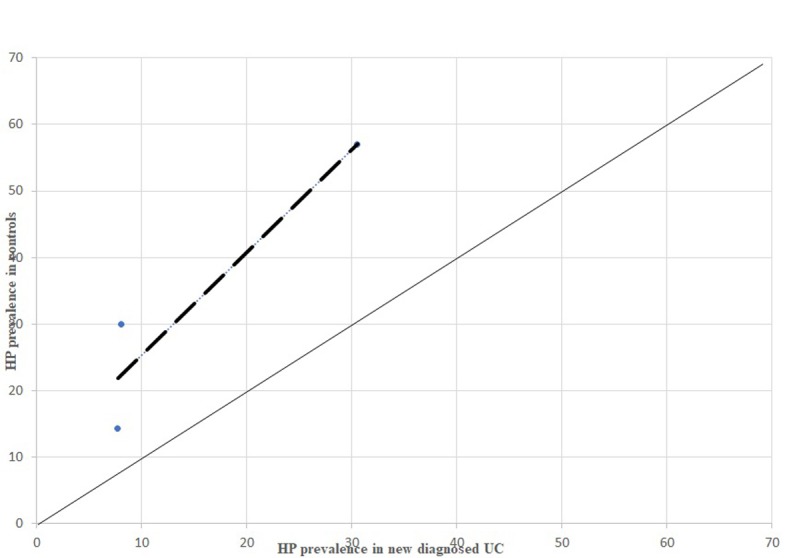

Figure 7.

P prevalence in newly diagnosed UC patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; UC: stands for Ulcerative Colitis

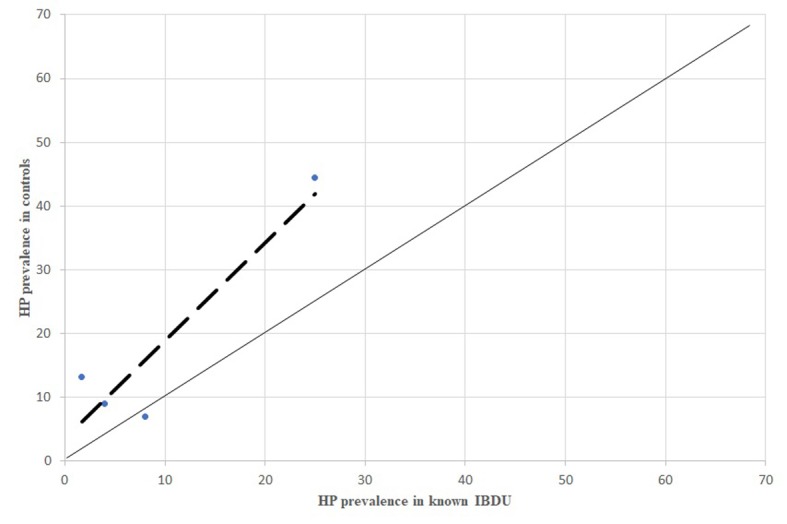

Figure 8.

P prevalence in known IBDU patients, comparison between dispersion line and 1:1 line. HP: stands for Helicobacter pylori; IBDU: stands for Unclassified Inflammatory Bowel Disease

From the analysis of HP prevalence carried out separately in studies considering newly diagnosed IBD patients (Figure 3, 5, 7) it is possible to assess that the inverse association previously reported is still confirmed in antibiotic- and immunosuppressant-free patients, even though less evident.

All the comparisons of HP infection prevalence carried out separately for CD, UC and IBDU patients showed the same inverse association between HP infection and the inflammatory bowel disease (Figures 4, 6, 8).

Conclusions

The key finding of this study is a striking inverse association between HP infection and the prevalence of IBD, independently from the type of IBD considered (CD, UC and IBDU) across distinct geographic regions.

The agreement among all the considered studies appears interesting from different points of view. Firstly, the same inverse association is confirmed by all the studies, although they considered different countries with different prevalence both of HP infection and IBD. Moreover, the analysis conducted separately on newly diagnosed IBD patients tends to eliminate the possible bias of previous use of antibiotics or immunomodulators which are routinely prescribed to followed up IBD patients, and still this analysis showed the same inverse association, although less strongly than if considering the overall population. Therefore, antibiotics seem to have an effect on HP infection prevalence, but they represent non-important confounders. However, case control studies displayed substantial methodologic and population heterogeneity, as well as publication bias which could have influenced the results (10). Furthermore, it is of note that many studies relied on HP serology with variable sensitivity and specificity compared to histology (11).

Several theories have proposed that IBD develop as a result of the dysbiosis between harmful and protective bacteria and also the imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory immune responses. Lack of childhood exposure to enteric pathogens responsible for gastroenteritis may have a role in the development of IBD. In this context, HP infection may simply be a marker of infection that reflects a generally increased exposure to gastrointestinal microbes.

In summary, the results from our review should be interpreted with caution. In our opinion HP infection could be a marker for an increased likelihood of exposure to other gastrointestinal infections or bacteria that, all together, may have an immunomodulatory effect. Anyway, we strongly disagree with any proposal against eradication of HP in infected patients, since it has been recognized as an human group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (12), this means a certain potential carcinogenic agent for gastric mucosa.

Overall, these first studies of association highlight the need of wider, prospective and more homogeneous research on this topic, which could open new scenarios on the theme of environmental etiology of IBD.

References

- 1.Matricon J, Barnich N, Ardid D. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Self/nonself. 2010;1(4):299–309. doi: 10.4161/self.1.4.13560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koloski NA, Bret L, Radford-Smith G. Hygiene hypothesis in inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review of the literature. World journal of gastroenterology. 2008;14(2):165–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valle J, Kekki M, Sipponen P, Ihamaki T, Siurala M. Long-term course and consequences of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Results of a 32-year follow-up study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1996;31(6):546–50. doi: 10.3109/00365529609009126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smythies LE, Waites KB, Lindsey JR, Harris PR, Ghiara P, Smith PD. Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosal inflammation is Th1 mediated and exacerbated in IL-4, but not IFN-gamma, gene-deficient mice. Journal of immunology. 2000;165(2):1022–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papamichael K, Konstantopoulos P, Mantzaris GJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: is there a link? World journal of gastroenterology. 2014;20(21):6374–85. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ram M, Barzilai O, Shapira Y, Anaya JM, Tincani A, Stojanovich L, et al. Helicobacter pylori serology in autoimmune diseases - fact or fiction? Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine. 2013;51(5):1075–82. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perri F, Clemente R, Festa V, De Ambrosio CC, Quitadamo M, Fusillo M, et al. Serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha is increased in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection and CagA antibodies. Italian journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 1999;31(4):290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elson CO. Genes, microbes, and T cells--new therapeutic targets in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):614–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202213460812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danese S, Sans M, Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: the role of environmental factors. Autoimmunity reviews. 2004;3(5):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Niv Y, O’Morain C. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease based on meta-analysis. United European gastroenterology journal. 2015;3(6):539–50. doi: 10.1177/2050640615580889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong YH, Sun LP, Jin SG, Yuan Y. Comparative study of serology and histology based detection of Helicobacter pylori infections: a large population-based study of 7,241 subjects from China. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;29(7):907–11. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0944-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearce N, Blair A, Vineis P, Ahrens W, Andersen A, Anto JM, et al. IARC monographs: 40 years of evaluating carcinogenic hazards to humans. Environmental health perspectives. 2015;123(6):507–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]