Abstract

Gastric cancer is, still nowadays, an important healthcare problem worldwide. In Italy, it represents the fifth tumour by frequency in both men and women over 70 years old. A crucial point is represented by the percentage of early gastric cancers usually found, which is actually very low, and it carries to a worse morbidity and mortality. The most important focus in this oncological disease, is to perform an effective detection of the most common precancerous lesion linked with this neoplasia, chronic atrophic gastritis, in order to avoid the future outcome of gastric cancer itself. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: gastric cancer, diagnosis, risk factors, epidemiology

About gastric adenocarcinoma (ADK), irrespective of histological classification, it is possible to divide the whole set in two main groups: ADK arising from the cardia (cardia gastric cancer or cardia GC) and from all other parts of stomach but cardia (no cardia gastric cancer or no cardia GC), as they have different epidemiologic patterns and causes (1).

Each year approximately 990.000 people are diagnosed with GC worldwide, of whom about 738.000 die from this disease. Concerning Italy, ISTAT (Istituto Superiore della Sanità, Higher Institute of Health) has elaborating interesting data about morbidity and mortality for cancer in Italy. Cancer is now the second cause of death (29%), right after cardiovascular diseases (37%). Concerning GC, in 2014 ISTAT reported 9,557 deaths caused by this disease (60% were men).

The 5-year survival in Italy for gastric cancer has a medium value of 31.8% with evident variations between young people (39.8%) and over 75 years old (21.6%).

Data provided by the Italian Association of Tumours Register (AIRTUM) in 2017 showed that GC is the fifth tumour by frequency (5%), in both men and women over 70 years old. Among patients with neoplasia, 6% of men between 50-69 years old and 7% over 70 years old dies because of GC; women over 70 years old are 7%.

In Italy the prevalence of GC varies from Southern Country (70 cases per 100,000 people) and Northern-Central Country (137 cases per 100,000 people), according with data given by AIRTUM.

GC incidence rates have been on decline in most part of the world (2,3). Despite this, there is a major exception: cardia GC rates have remained stable or increased (4,5), in Western Countries. Such contrasting trends between cardia and no cardia GC may result from different aetiologies. For example, Helicobacter Pylori doesn’t seem to be a risk factor for cardia GC in Western Countries (6), so its declining prevalence would not be expected to affect cardia GC rates. Conversely, obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), seem to be risk factors only for cardia GC. This is a very important notion because obesity has been increasing in prevalence in Western Countries (7) and GERD is an increasing pathology in our reality.

Comparing nations, the highest incidence rates are in East Asia, East Europe and South America, meanwhile the lowest rates are observed in North America and most parts of Africa (8). For example, the annual age-standardized GC incidence rates per 100.000 in men is 65.9 in Korea versus 3.3 in Egypt (9). Particular indigenous populations just like Inuits (in the circumpolar region) and Maoris (in New Zealand), suffer from high rates of GC (10).

This kind of cancer is more common in men (rates are 2 to 3 folds higher in men compared to women) (11).

Early gastric cancer (Early GC) is an invasive cancer confined to mucosa and/or submucosa, with or without lymph node metastases, irrespective of the tumour size (12). Most Early GC are small (up to 5 cm in size), and those are usually located at lesser curvature around angularis. Some Early GC are multifocal, often indicative of a worse prognosis. It is possible to divide Early GC into: type I (for a tumour with protruding growth), type II (superficial growth), type III (excavating growth), and type IV (infiltrating growth with lateral spreading).

The prognosis of Early GC is excellent, with a 5 years survival rate of 90% (13).

In contrast, the advanced gastric cancer (Advanced GC), that invades into muscularis propria or beyond, has a much worse prognosis, with a 5 years survival rate at about 60% or less (14). The appearance of Advanced GC can be exophytic, ulcerated, infiltrative or combined. Based on Borrmann’s classification, the appearance of this kind of cancer can be divided into type I (polypoid growth), type II (fungating growth), type III (ulcerating growth) and type IV (diffusely infiltrating growth).

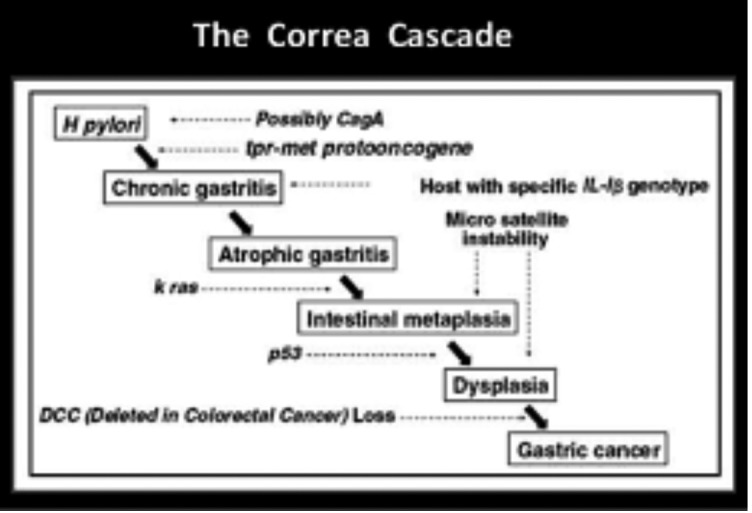

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma is the most frequent GC. It develops through a cascade of precancerous lesions such as atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia (Correa’s cascade of gastric carcinogenesis) (15) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correa’s cascade

Chronic gastritis is the result of a chronic inflammation of the mucosa, where the appropriate native gastric glands can be replaced by fibrous tissue, giving shape to non-metaplastic atrophic gastritis, and/or by pyloric type glands or, more often, by intestinal type glands that indicates the presence of a metaplastic atrophic gastritis (16).

Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia associate with an increased risk of developing gastric cancer as they constitute conditions in which dysplasia develops.

Risk factors

Several different risk factors are involved. It is possible to identify two different groups: not modifiable (older age, male sex, ethnicity, familiar history and presence of predisposing syndromes) and modifiable risk factors (voluptuous habits such as tobacco smoking, alcohol abuse, exposure to radiations, Helicobacter Pylori infection, etc...).

Moreover, is possible to identify risk factors that are typically linked with cardia gastric cancer, others linked with no cardia gastric cancer or linked with both kinds of neoplasia.

Common risk factors include:

Age: the incidence rate of GC rises progressively with age. Among all cases diagnosed between 2005 and 2009 in the USA, approximately 1% of those occurred in young patients (age between 20 and 34 years), meanwhile 29% occurred in old patients (age between 75 and 84 years). The median age at diagnosis of GC was 70 years (17).

Male sex: males have higher risk of both cardia and no cardia (5-fold) and no cardia (2-fold) GC (18). The exact reason is not actually clear. In past, men were more likely to smoke tobacco, and this could have been important, but this data is now of a lesser importance in most countries because smoking is nowadays, a very common habit in both sexes.

Tobacco smoking: in 2002 IARC (international agency for research on cancer) establish that smoking has a role as a risk factor in GC onset, saying that there is a “sufficient evidence of causality between smoking and GC (19).

Race: in white people, cardia GC is about twice as common as in the other racial groups, but no cardia GC is half as common (20). The association of race with incidence of GC seems to be mediated by environmental effects, rather than genetic variations.

Radiations: long-term follow up on Hiroshima and Nagasaki disaster established radiations as risk factor for GC (21). Even more recent studies were done on survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and also showed that radiation to the stomach has a dose-response association with higher risk of GC. This effect is particularly evident in patients that at the same time received procarbazine.

Cardia gastric cancer risk factors include:

Obesity: this is a growing problem in our society and it has been linked with several different diseases, including GC. People with a BMI of 30 to 35 have two-fold risk compared with people with BMI of <25 and those with a BMI > 40 have a three-fold risk of cancers of the esophagogastric junctional, including the cardia GC (22).

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD): this pathology is strictly connected with risk of onset of esophageal adenocarcinoma with a 5-7-fold increase risk (23). Several studies have reported statistically significant association between GERD and cardia GC (24), with increased risks of 2-4 folds, in most of studies.

No cardia gastric cancer risk factors include:

Helicobacter Pylori: H. Pylori is a sure cause of GC (23) with relative risks of approximately 6 for no cardia GC (25). The H. Pylori that are positive for the virulence factor cytotoxin-associated gene A (Cag A), are more likely to cause GC (26, 27). It is not sure how H. Pylori causes the cancer onset. Two potential pathways are mostly considered: indirect action of the bacteria on gastric epithelial cells by causing inflammation and direct action: H. Pylori could also directly modulate epithelial cells function through bacterial agents, such as Cag A. Nevertheless, the relation between the two pathways is still unclear, both ones seem to work together to promote GC development.

H. Pylori is estimated to cause from 65% to 80% of all GC cases, about 660.000 new cases each year (28, 29).

Intake of salty and smoked food: the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) has concluded that “salty and salt-preserved foods are probably cause of GC (30). Large cohort studies were done in Korea, they had shown that people who tend to prefer salty food have higher risk of GC (31). Salt may increase the risk of GC through direct damage to gastric mucosa conducing to gastritis or other mechanisms (32).

Genetic risk factors also exist:

Only 1-3% of GC cases are result of inherited syndromes (33).

Those syndromes include hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC), which is a rare disease. It is an autosomal dominant inherited form of GC usually with an highly invasive diffuse type cancer.

It has a late presentation and a poor prognosis. In this kind of cancers there is a loss of expression of cell adhesion protein: E-caderin. Furthermore, about 25% of families with HDGC have inactivating CDH1 germline mutations.

Another syndrome is FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis), an autosomal dominant colorectal cancer syndrome caused by a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Those patients have a risk of 100% of colorectal cancer by the age of about 40 as well as an high risk of other neoplasia, including GC.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: is a rare autosomal dominant condition, linked with hamartomatous gastrointestinal polyposis and melanin spots on the lips and buccal mucosa. The cause is mutation of LKB1 gene, which encodes a serine/threonine kinase that acts as a suppressor.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): before the advent and use of genome-wide scans, a lot of case-control studies examined in deep candidate polymorphisms (mostly chosen based on biologic plausibility) in relation to GC.

Although some of those associations showed promise, quite all failed to replicate. For example, the initially exciting associations among polymorphisms in inflammatory genes (especially IL-1B), were not replicated in future studies (34), including in genome wide association studies.

Significant associations between SNPs at 1q22, located in Mucin 1 gene (MUC1), and GC were reported in the GWAS of Japan and Korean studies. Meta-analysis of the results identified several other SNPs in MUC1 that were significantly associated with GC risk (35). The mechanism of action is not clear for any of those polymorphisms. However, these findings will lead to mechanistic insight into gastric carcinogenesis.

Concerning Helicobacter pylori infection, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, we associated eradication of H pylori infection with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer. The benefits of eradication vary with baseline gastric cancer incidence, but apply to all levels of baseline risk (36). Real world data showed that large-scale eradication therapy has been performed mostly for benign conditions in Japan. Since eradication effects in preventing gastric cancer are conceivably greater there, GC incidence may decline faster in Japan than expected from the previous meta-analyses data which were based on multi-national, mixed populations with differing screening quality and disease progression (37).

Concerning early diagnosis worldwide, an accurate review carried out in 2014 pointed out that its rate is actually very low and this state is also due to the lack of early symptoms and the high difficulty to make a proper endoscopic diagnosis (even because it often shows only subtle changes ) (38).

Further evaluations were recently carried out on some Italian areas. The situation in northern Italy shows a very poor early diagnosis percentage in two different populations that have been studied since 2011, Altovicentino (nearby Vicenza) and Parma district.

Early diagnosis rate in Parma district was of 10,5% and in Altovicentino of 6% (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Early diagnosis rates in Altovicentino and Parma district study groups.

Conclusion: As as it is possible to understand from the evaluated information, gastric cancer is, still nowadays, an important healthcare burden worldwide. Even if the global incidence is decreasing, the mortality rates among those patients are unfortunately high. Several different risk factors exist but the main recognized risk factor for no cardia GC is the H.pylori infection. Those data underline the effectiveness of H.pylori eradication in order to avoid further gastric lesions, especially in countries with an high rate of gastric cancer outset just like East Asia ones. The importance of early diagnosis of precancerous lesions (such as atrophic gastritis) is underlined too, even through non-invasive serological tests such as Gastropane®, trying to effectively prevent the onset of neoplasia, an even more decisive point in the oncological field than the diagnosis of early stage gastric cancer itself.

References

- 1.Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening and prevention. Cancer epidemiol biomarkers prev. 2014 May;32(5):700–13. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. In J Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:2137–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Levi F, Chatenoud L, Negri E, et al. Cancer mortality in Europe, 2005-2009and an overview of trends since 1980. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2657–71. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devesa SS, Blot JW, Fraumeni JF. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell J, McConkey CC. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia and adjacent sites. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:440–3. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavaleiro-Pinto M, Peleteiro B, Lunet N, Barros H. Helicobacter Pylori and gastric cardia cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:375–87. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields M, Carroll MD, Ogden LO. Adult obesity prevalence in Canada and the United States. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD. 2011 Data brief, no 56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forman D, Burley V. Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:633–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893–907. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold M, Moore SP, Hassler S, Ellison-Loschmann L, Forman D, Bray F. The burden of stomach cancer in indigenous populations: a systematic review and global assessment. Gut. 2014;63:64–71. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton R, Aatonen LA. Tumors of Digestive System. Lyon:IARC. 2000:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett SM, Axon AT. Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut. 1997;41:142–50. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa K, Maruyama K. Characteristics of gastric cancer invading to the proper muscle layer--with special reference to mortality and cause of death. Jpn J ClinOncol. 1985;15:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process- first American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Research. 1992;52(24):6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, et al. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) Endoscopy. 2012;44:74–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maehara Y, Kakeji Y, Koga T, et al. Therapeutic value of lymph node dissection and the clinical outcome for patients with gastric cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:S85–91. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2088; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–56. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Ingested nitrate and nitrite, and cyanobacterial peptide toxins. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;94:1–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Serag H, Mason A, Petersen N, Key C. Epidemiological differences between adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia in the USA. Gut. 2002;50:368–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preston DL, Ron E, Tokuoka S, Funamoto S, Nishi N, Soda M, et al. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors:1958-1998. Radiat Res. 2007;168:1–64. doi: 10.1667/RR0763.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyo C, Cook MB, Kamangar F, Freedman ND, Whiteman DC, Bernstein L, et al. Body mass index in relation to oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON Consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1706–18. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubenstein JH, Taylor JB. Meta-analysis: the association of oesophageal adenocarcinoma with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1222–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamangar F, Sheikhattari P, Mohebtash M. Helicobacter Pylori and its effects on human health and disease. Arch Iran Med. 2011;14:192–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gastric cancer and H. Pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Cag A seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiota S, Suzuki R, Yamaoka Y. The significance of virulence factors in H. Pylori. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:341–9. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiserman M. The second world cancer research fund/ American Institute for Cancer Research expert report. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:253–6. doi: 10.1017/S002966510800712X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, Park S, Nam BH. Gastric cancer and salt preference: a population-based cohort study in Korea. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1289–93. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsugane S, Sasazuki S, Kobayashi M, Sas AD, Ki S. Salt and salted food intADKe and subsequent risk of gastric cancer among middle-aged Japanese men and women. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:128–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch HT, Grady W, Suriano G, Huntsman D. Gastric cancer: new genetic developments. J Surg Oncol. 2005;90:114–33. doi: 10.1002/jso.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Y, Hu Z, Wu C, Dai J, Li H, Dong J, et al. A genome wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for non-cardia gastric cancer at 3q13.31 and 5p13.1. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1215–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee YC1, Chiang TH2, Chou CK, et al. Association Between Helicobacter pylori Eradication and Gastric Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016 May;150(5):1113–1124. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.028. e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.028. Epub 2016 Feb 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugano K. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric cancer. 2018 Sep 11 doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0. Doi:10.1007/s10120-018-0876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasechnikov V, Chukov S, Fedorov E, et al. Gastric cancer: prevention, screening and early diagnosis. World J Gastroenterology. 2014 October 14 doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]