Abstract

Background:

Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe diarrhea among young children worldwide. Rotavirus vaccines have demonstrated substantial benefits in many countries that have introduced vaccine nationally. In China, where rotavirus vaccines are not available through the national immunization program, it will be important to review relevant local and global information to determine the potential value of national introduction. Therefore, we reviewed evidence of rotavirus disease burden among Chinese children <5 years of age to help inform rotavirus vaccine introduction decisions.

Methods:

We reviewed scientific literature on rotavirus disease burden in China from 1994 through 2014 in CNKI, Wanfang and Pubmed. Studies were selected if they were conducted for periods of 12 month increments, had more than 100 patients enrolled, and used an accepted diagnostic test.

Results:

Overall, 45 reports were included and indicate that rotavirus causes ~40% and ~30% of diarrhea-related hospitalizations and outpatient visits, respectively, among children aged <5 years in China. Over 50% of rotavirus-related hospitalizations occur by age 1 year; ~90% occur by age 2 years. Regarding circulating rotavirus strains in China, there has been natural, temporal variation, but the predominant local strains are the same as those that are globally dominant.

Conclusions:

These findings affirm that rotavirus is a major cause of childhood diarrheal disease in China and suggest that a vaccination program with doses given early in infancy has the potential to prevent the majority of the burden of severe rotavirus disease.

Keywords: rotavirus, diarrhea, gastroenteritis, rotavirus vaccines

INTRODUCTION

Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhea in children worldwide [1]. Annually, it causes approximately 200,000–453,000 deaths [2], 2 million hospitalizations, and 25 million outpatient visits in children <5 years of age [3]. Currently, vaccination is the primary tool for prevention of rotavirus disease, and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that rotavirus vaccines be included in all national immunization programs as part of a comprehensive strategy to control diarrheal diseases [4]. In China, past studies have indicated that rotavirus infection accounts for ~40% of all acute gastroenteritis hospitalizations in children aged<5 years [5]. However, rotavirus vaccine currently is not included in the Chinese Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) routine immunization schedule. As opposed to a vaccine provided through the EPI (also known as “Type 1” vaccines), a locally manufactured, live attenuated, oral, lamb rotavirus G10P[12] strain vaccine, Lanzhou Lamb Rotavirus (LLR) vaccine (Lanzhou Institute of Biological Products, Lanzhou, China), has been available on the private market since 2000 as a “Type 2” vaccine (i.e., a vaccine licensed for the manufacturer to sell in clinics or provider offices) [6].

Given the WHO recommendation for inclusion of rotavirus vaccines in all national immunization programs and the increasing evidence of the benefits of rotavirus vaccination in other countries [6], it will be important for decision makers to review relevant local and global information to determine the potential value of a national rotavirus vaccination program in China. This paper provides a comprehensive review of the scientific literature published over the last two decades on rotavirus disease burden and strain distribution in children <5 years of age in China, and considerations for vaccine introduction in China.

METHODS

Sources of data

For rotavirus disease burden estimates and strain distribution, we identified references through searches of PubMed and two Chinese literature databases (National Knowledge Infrastructure, China [CNKI] and Wanfang) for articles published from 1 January 1994 to 31 December 2014, by use of the terms (“rotavirus” and “China”) or (“diarrhea” and “China”). The term “China” was used for PubMed search only. Chinese language (”腹泻”或“轮状病毒”) was used for the CNKI and Wanfang searches. We then manually screened all English and Chinese language articles resulting from these searches for study population, study duration, and rotavirus diagnostic methods. Articles that met the following criteria were fully abstracted and included in this report: 1) data available for 100 or more patients <5 years of age; 2) study duration of at least 12 month increments (to account for seasonality of disease); and 3) use of the following rotavirus laboratory tests on fecal samples – enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for rotavirus detection and/or reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for strain typing. We excluded literature reviews, studies reporting on adults only, and reports on outbreaks and nosocomial infections.

Categorization of rotavirus disease burden and strain distribution studies

We stratified rotavirus disease burden studies by health care setting (inpatient and outpatient) and by geographic location (urban and rural). For each study reviewed, we used a standardized form to abstract the rotavirus detection rate, health care setting, geographic location, study duration, and study population size. For inpatient studies that provided age-stratified data, we pooled the number of children enrolled by age to determine the cumulative age distribution for rotavirus-related hospitalizations. Since predominant rotavirus strains may change over time, we examined strain distribution by the following time periods for which data were available: 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2013.

RESULTS

Rotavirus disease burden

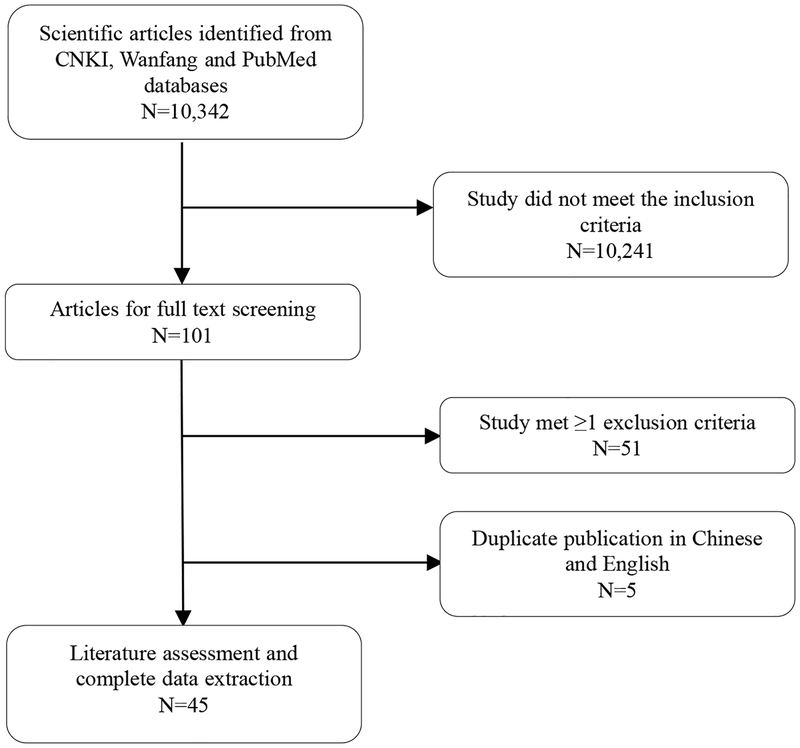

The initial search identified 10,342 rotavirus-related citations from CNKI, Wanfang, and PubMed. Forty-five studies met the inclusion criteria for review (Figure 1). Thirty-nine studies were published in Chinese, and six were published in English. Of the 45 included studies, 39 provided data on inpatient health care visits, with study periods ranging 12–60 months [7–45]and 10 provided data on outpatient health care visits, with study periods ranging 12–36 months [7, 8, 36, 42, 46–51].

Figure 1.

Eligibility of studies for inclusion in the systematic review

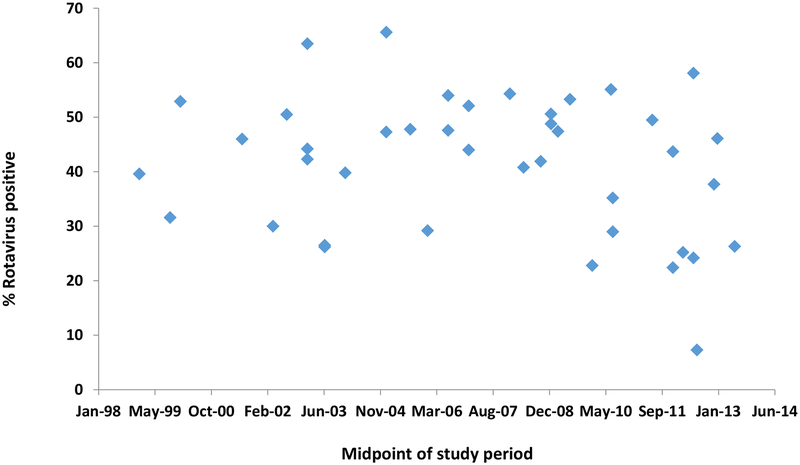

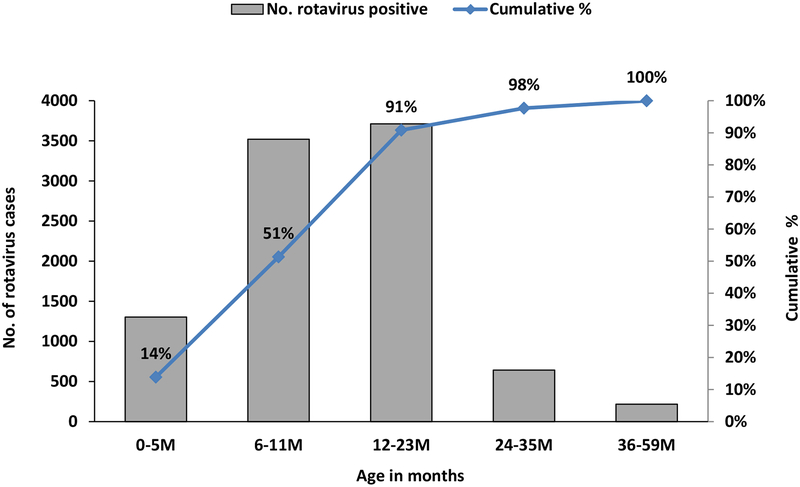

For the 39 inpatient studies conducted between 1998 and 2013, a total of 74,846 (range per study: 169–14,511) children <5 years of age with acute gastroenteritis were evaluated (Table 1) for which a median of 44% (range: 7.3%−65.6%) of these children tested positive for rotavirus; the proportion of diarrhea hospitalizations due to rotavirus was stable over the 16 year period (Figure 2). The median proportion of children that tested positive for rotavirus did not vary greatly by geographic region (range for North, Central, and Southern regions: 37.7%−47.3%). Thirty-three studies were conducted in urban areas (median rotavirus positive: 39.8%, range: 7.3%−65.6%), and 6 were conducted in rural areas (median rotavirus positive: 46.7%, range: 43.7%−54.3%). For pooled data on cumulative rotavirus hospitalization incidence from 12 studies, 14% of rotavirus gastroenteritis hospitalizations occurred in children aged <6 months, and 91% of rotavirus gastroenteritis hospitalizations occurred by age <24 months (Figure 3) [8, 12–14, 26, 29, 31, 49, 52–55].

Table 1.

Rotavirus detection rates for 41 inpatient studies of pediatric diarrhea among children <5 years of age in China, 1998–2013

| Location | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period (year/month) | Duration (months) | Number | % rotavirus positive | Reference | |

| Northern China | |||||

| Urban | |||||

| Beijing | 1998/4–2001/3 | 36 | 209 | 31.6 | [7] |

| Beijing | 2013/1–2013/12 | 12 | 243 | 26.3 | [43] |

| Changchun | 1998/7–2001/6 | 36 | 1056 | 52.9 | [8] |

| Changchun | 2001/8–2004/7 | 36 | 1227 | 63.5 | [9] |

| Changchun | 2004/7–2005/6 | 12 | 400 | 47.3 | [10] |

| Changchun | 2010/1–2010/12 | 12 | 460 | 35.2 | [11] |

| Changchun | 2005/1–2013/12 | 108 | 3934 | 53.3 | [45] |

| Changchun | 2012/1–2012/12 | 12 | 387 | 58.1 | [44] |

| Hebei | 2006/1–2006/12 | 12 | 454 | 47.6 | [12] |

| Lanzhou | 2005/1–2007/12 | 36 | 544 | 54.0 | [14] |

| Liaoning | 2009/1–2011/12 | 36 | 169 | 29.0 | [15] |

| Chizhou | 2005/1–2006/12 | 24 | 428 | 29.2 | [33] |

| Rural | |||||

| Lulong | 1999/7–2003/6 | 48 | 1236 | 46.0 | [16] |

| Lulong | 2001/8–2004/7 | 36 | 945 | 44.2 | [9] |

| Lulong | 2007/1–2010/12 | 48 | 1643 | 48.8 | [13] |

| Lulong | 2008/9–2009/8 | 12 | 426 | 47.4 | [17] |

| Lulong | 2011/1–2012/12 | 24 | 741 | 43.7 | [34] |

| Northern China median (range) | 460 (169–3934) | 47.3 (26.3–63.5) | |||

| Central China | |||||

| Urban | |||||

| Henan | 2004/1–2005/12 | 24 | 1628 | 65.6 | [18] |

| Hunan | 2009/1–2010/12 | 24 | 759 | 22.8 | [19] |

| Taiyuan | 2007/11–2008/10 | 12 | 346 | 40.8 | [20] |

| Taiyuan | 2010/1–2012/12 | 36 | 989 | 49.5 | [35] |

| Nanchang | 2009/7–2011/6 | 24 | 390 | 55.1 | [36] |

| Anhui | 2011/1–2012/12 | 24 | 549 | 22.4 | [37] |

| Anhui | 2011/4–2013/3 | 24 | 310 | 25.2 | [38] |

| Central China median (range) | 549 (310–1628) | 40.8 (22.4–65.6) | |||

| Southern China | |||||

| Urban | |||||

| Guangzhou | 2002/1–2005/12 | 48 | 399 | 39.8 | [21] |

| Hong Kong | 2001/4–2003/3 | 24 | 5881 | 30.0 | [22] |

| Kunming | 2001/8–2004/7 | 36 | 949 | 42.3 | [9] |

| Meizhou | 2008/4–2009/3 | 12 | 568 | 41.9 | [23] |

| Shanghai | 2001/1–2005/12 | 60 | 5534 | 26.2 | [24] |

| Shanghai | 2001/1–2005/12 | 60 | 5411 | 26.5 | [25] |

| Shanghai | 2012/2–2013/1 | 12 | 619 | 7.3 | [39] |

| Zhuhai | 2008/7–2009/6 | 12 | 478 | 50.6 | [26] |

| Shenzhen | 2011/1–2013/12 | 36 | 14511 | 24.2 | [41] |

| Guiyang | 2012/1–2013/12 | 24 | 1607 | 37.7 | [40] |

| Rural | |||||

| Luocheng | 2007/1–2008/12 | 24 | 617 | 54.3 | [27] |

| Southern China median (range) | 949 (399–14,511) | 37.7 (7.3–54.3) | |||

| Various locations | |||||

| 8 cities | 1998/1–1999/12 | 24 | 1093 | 39.6 | [28] |

| 6 sentinel hospitals | 2001/8–2003/7 | 24 | 3149 | 50.5 | [29] |

| 11 sentinel hospitals | 2003/8–2007/7 | 48 | 7846 | 47.8 | [30] |

| 9 cities | 2006/1–2007/12 | 24 | 3862 | 44.0 | [31] |

| 3 cities | 2006/1–2007/12 | 24 | 2328 | 52.1 | [32] |

| 2 cities | 2012/8–2013/7 | 12 | 521 | 46.1 | [42] |

| Median (range) of all studies | 741 (169–14,511) | 44 (7.3–65.6) | |||

Figure 2.

Rotavirus positivity by study midpoint in children age <5 years hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis, 1998–2013

Figure 3.

Age distribution of children hospitalized with acute rotavirus gastroenteritis in China, 1998–2013. Bars denote the number of hospitalizations in different age groups and the line represents the cumulative rotavirus-positive rate.

In 10 outpatients studies conducted between 1998 and 2013, a total of 16,994 (range per study: 155–10,140) children <5 years of age with acute gastroenteritis were evaluated (Table 2). A median of 30.7% (range: 12.3%−35.4%) of these children tested positive for rotavirus. The proportion of children that tested positive for rotavirus was reported as 27.3%−35.4% in 3 studies conducted Northern China, 30.8% in 1 study conducted in Central China, 12.3%−30.7% in 5 studies conducted in Southern China, and 31% in one study conducted various locations in Gansu Province. All studies were conducted in urban areas.

Table 2.

Rotavirus detection rates for 10 outpatient studies of pediatric diarrhea among children <5 years of age in urban China, 1998–2013

| Location | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period (year/month) | Duration (months) | Number | % rotavirus positivea | Reference | |

| Northern China | |||||

| Beijing | 1998/4–2001/3 | 36 | 275 | 27.3 | [7] |

| Changchun | 1998/7–2001/6 | 36 | 155 | 31.0 | [8] |

| Rizhao | 2007/1–2009/12 | 36 | 997 | 35.4 | [46]b |

| Central China | |||||

| Nanchang | 2009/7–2011/6 | 24 | 234 | 30.8 | [36] |

| Southern China | |||||

| Jinzhou | 2003/1–2004/12 | 24 | 646 | 30.7 | [48] |

| Xiamen | 2009/1–2011/12 | 36 | 2566 | 30.6 | [49] |

| Shaoxing | 2010/1–2012/12 | 36 | 10140 | 12.3 | [55] |

| Guangzhou | 2011/6–2013/5 | 24 | 709 | 21.6 | [50] |

| Pinghu | 2013/1–2013/12 | 12 | 1059 | 23.6 | [51] |

| Various locations | |||||

| 2 cities | 2012/8–2013/7 | 12 | 213 | 31.0 | [42] |

| Median(range) | 623(155–10,140) | 30.8(12.3–52.0) | |||

Detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay;

included children 60 months of age

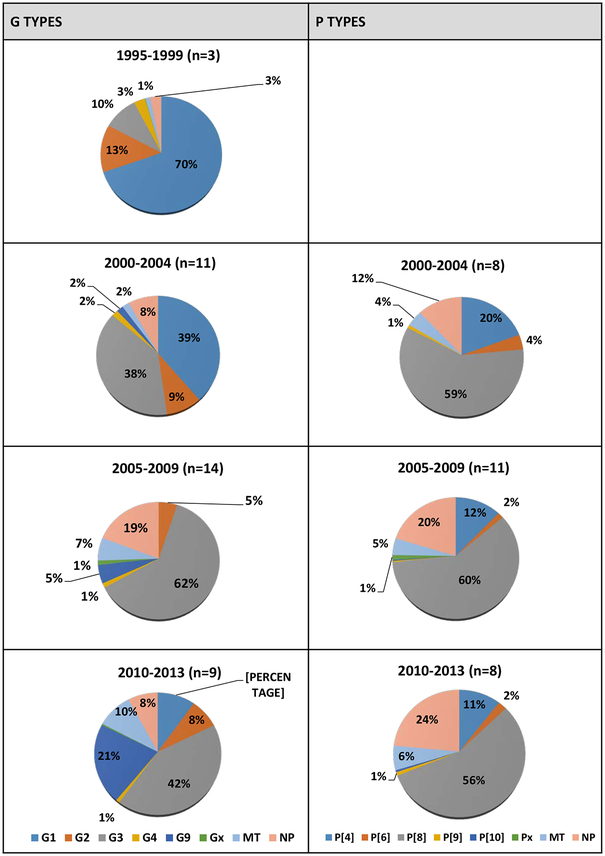

Rotavirus strain distribution

We examined rotavirus strain distribution data for the years 1995–2013 from 35 studies that met the inclusion criteria [7, 8, 10–14, 17, 19, 20, 24, 27–29, 32, 35, 38, 45, 47, 52–67] (Figure 4). In 3 studies with data for 1995–1999, G1 was the predominant reported G type, accounting for 70% of strains; data on P types were not available for this time period. In 11 studies with data for 2000–2004, G1 and G3 were the predominant reported G types, accounting for 39% and 38% of strains, respectively. In 8 studies for which P types were reported during the same period, P[8] was predominant, accounting for 59% of strains. In 14 studies with data for 2005–2009, G3 was the predominant reported G type, accounting for 62% of strains, while in 11 studies for the same time period, P[8] was the predominant reported P type, accounting for 60% of strains. In 9 studies with data for 2010–2013, G3 was the predominant reported G type, accounting for 42.3% of strains, while in 8 studies for the same time period, P[8] was the predominant reported P type. No uniform differences in genotype predominance by region were seen within each time period.

Figure 4.

Distribution of common G and P types in children<5 years old in China, 1995–2013a

a MT=mixed type, NP=non-typeable

DISCUSSION

The findings of this comprehensive, up-to-date literature review affirms that rotavirus is a leading cause of severe diarrheal disease among children in China, causing over 40% of diarrhea hospitalizations and ~30% of diarrhea-related outpatient visits in children aged <5 years. The proportion of diarrhea hospitalizations due to rotavirus was remarkably stable over the 16 year period from 1998 to 2013 and also was similar in different geographic regions and urban/rural settings. Severe rotavirus disease occurs early in life in China with over half of rotavirus-related hospitalizations occurring in the first year of life and 91% of rotavirus related hospitalizations occurring by 2 years of age. However, it is important to note that only 14% of hospitalizations occurred prior to the age of 6 months. Therefore, a vaccination program with doses given early in infancy has the potential to prevent the majority of the burden of severe rotavirus disease. Our review also demonstrates that, while there has been natural, temporal variation in circulating rotavirus strains in China, the predominant local strains are the same as those that are globally dominant [68, 69].

Using estimates of approximately 30 million doses of LLR vaccine distributed since 2000 and a birth cohort of 16 million, the crude national LLR vaccination coverage is only 15.6% with one dose. This may help explain why we observed steady rotavirus positivity rates in our review of the literature even after 2000, the year of vaccine licensure. However, without accurate national and local population coverage data, it is difficult to gauge the true level of impact that LLR vaccine may have had on rotavirus disease trends in China and whether decreases in rotavirus disease in specific areas were due to vaccine use. More scientifically rigorous studies are essential to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of this vaccine.

This review has some limitations. First, due to its retrospective nature, people in studies are not the same. Second, given strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, a greater proportion of the included studies were from urban location, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, we were unable to obtain national level data that would have covered more provinces of China, including the poorest areas in western China. Third, we were unable to include all studies identified through the literature searches given different study periods, ages of enrollment, case definitions of severity, and diagnostic assays used. However, by using a uniform set of inclusion criteria, we were able to compare studies over time, across regions, by urban/rural location, and by clinical setting as a marker of disease severity where hospitalizations represent more severe disease. Despite these limitations, we were able to review a large number of studies, and the detection rates observed in this review are similar to those found in the most recent large prospective study in China [70].

The introduction of rotavirus vaccines into routine immunization programs worldwide has resulted in substantial declines in rotavirus-related morbidity and mortality in the countries that have introduced vaccine [6, 71]. The two globally recommended rotavirus vaccines, Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) and RotaTeq (Merck and Co. Inc, Pennsylvania, USA), have been introduced into over 75 countries worldwide since 2006 and have had good effectiveness against severe rotavirus disease under conditions of routine use and a notable impact in reducing rotavirus hospitalization in many countries 72, 73]. Currently in China, the two globally recommended rotavirus vaccines and a new trivalent lamb-human reassortant rotavirus vaccine are in pre-licensure clinical trials, and several other locally manufactured rotavirus vaccines are in development.

Our findings affirm that rotavirus is the major cause of childhood diarrheal disease in China and suggest that a vaccination program with doses given early in infancy has the potential to prevent the majority of the burden of severe rotavirus disease. This information should help inform future decisions on national rotavirus vaccine introduction in China.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to Zijian Feng and Zhaojun Duan of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their grant support.

Financial support: Grant support provided by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, et al. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. ; WHO-coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresee JS, et al. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:304–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Rotavirus vaccines. WHO position paper – January 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;88:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YYW. Annual report on surveillance of selected infectious diseases and vectors, China, 2007. Annual report of viral diarrhea surveillance; 2009:279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu QL, et al. Aetiology surveillance of virus diarrhea in Hebei Province in 2006. Chinese Gen Practice. 2008;11:479–481. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel MM, Glass R, Desai R, et al. Fulfilling the promise of rotavirus vaccines: how far have we come since licensure? Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong ZL, Ma L, Zhang J, et al. Epidemiological study of rotavirus diarrhea in Beijing, China - a hospital-based surveillance from 1998 – 2001. 2003;24:1100–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun LW, Tong ZL, Li LH, et al. Surveillance finding on rotavirus in Changchun children’s hospital during July 1998-June 2001. Chinese J Epidemiol. 2003;24:1010–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang LJ, Fang ZY, Sun LW, et al. Rotavirus diarrhea among children in three hospitals under sentinel surveillance, from August 2001 to July 2004. Chinese J Epidemiol. 2007;28:473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye XH, Jin Y, Fang ZY, et al. Etiological study on viral diarrhea among children in Lanzhou, Gansu, from July 2004 through June 2005. Chinese J Epidemiol. 2006;27:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang XE, Li DD, Li X, et al. Etiological and epidemiological study on viral diarrhea among children in Changchun. Chinese J Exp Clin Virol. 2012;26:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu QL, Shen YX, Xie Y, et al. Surveillance of group A rotavirus infection in children with diarrhea in Lulong County, Hebei Province, 2007–2010. Int J Virol. 2011;18:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y, Cheng WX, Yang XM, et al. Viral agents associated with acute gastroenteritisin children hospitalized with diarrhea in Lanzhou, China. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An SY, Zhao Z, Guo JQ, et al. Epidemiological study on viral diarrhea during 2009–2011 in Liaoning Province. Chinese J Infectious Dis. 2013;31:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Q, Tang JY, Hu HK, et al. Epidemiology survey on virological diarrhea among children in rural of Qinhuangdao city. Chinese J Public Health. 2006;22:1048–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li DD, Yu QL, Qi SX, et al. Study on the epidemiological of rotavirus diarrhea in Lulong in 2008–2009. Chinese J Exp Clini Virol. 2010;24:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qun-li H and Li-qun M. Research on etiology of infantile diarrhea in Northern Henan. J Applied Clin Pediatr. 2007;22:497–527. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li JH, Zhou SF, Liu YZ, et al. Etiological study on viral diarrhea among infants and young children in surveillance hospitals of Hunan Province from 2009 to 2010. Pract Prev Med. 2012;19:337–341. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan B, Li J, Li DD, et al. Analysis on epidemiologic characteristics of viral diarrhea among infants in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, 2007–2008. Chinese J Exper Clin Virol. 2010;24:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jian-zhong M and Qing-ri M. Clinical and etiological analysis of 452 infectious diarrhea cases in children. Public Med Forum Mag. 2006;10:312–313. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson EA, Tam JS, Bresee JS, et al. Estimates of rotavirus disease burden in Hong Kong: hospital-based surveillance. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(suppl 1):S71–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guang-wen X, Wei-dong W, Yan-peng X. Survey of pathogen of acute infant viral diarrhea in Meizhou City. China Trop Med. 2010;10:417–418. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin X, Sun JE, Ding YZ, et al. Molecular epidemiology of group A rotavirus in 1450 hospitalized children in Shanghai, China, 2001–2005. Chinese J Evid Pediatr. 2007;2:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Yang Y, Sun J, et al. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus infections among children hospitalized for acute gastroenteritis in Shanghai, China, 2001 through 2005. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng FP, Cheng HJ, Huang H. Epidemiology survey of infection of human rotavirus. China Med Pharm. 2011;01:132,134. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Min-mei C, Kai-jiao C, Zhao-jun M, et al. Molecular epidemiologic study of rotavirus diarrhea among children in Luocheng County, Guangzhou, 2007–2008. J App Prev Med. 2010;16:75–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang ZY, Qi J, Yang H, et al. Genotyping of rotavirus diarrhea in infants and young children from 1998 to 1999. Chinese J Virol. 2001;17:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang ZY, Wang B, Kilgore PE, et al. Sentinel hospital surveillance for rotavirus diarrhea in the People’s Republic of China, August 2001-July 2003. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(Suppl 1):S94–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan ZJ, Liu N, Yang SH, et al. Hospital-based surveillance of rotavirus diarrhea in the People’s Republic of China, August 2003-July 2007. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(Suppl 1):S167–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su-hua Y, Hong W, Na L, et al. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus among children under 5 years old hospitalized for diarrhea in China. Chinese J Exper Clin Virol. 2009;23:168–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li DD, Liu N, Yu JM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of G9 rotavirus strains in children with diarrhoea hospitalized in Mainland China from January 2006 to December 2007. Vaccine. 2009;27(suppl 5):F40–F45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ping WG. Study on viral pathongens for infant diarrhea in Chizhou, Anhui. Chinese J Exper Clin Virol. 2009;23:292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu CX, Duan ZJ, Liu N, et al. Epidemiological study on infantile viral diarrhea in rural areas from 2011 to 2012. Maternal Child Health Care China. 2014;29:2915–2917. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren BZ, Zhao R, Wang NC, et al. Study on the epidemic characteristics and serotype diversifies of rotavirus among patients with viral diarrhea under five years old in Taiyuan between 2010 and 2012. J Pract Med Tech. 2014;21:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou BH, Tu QF, Shen L, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and molecular epidemiology study on rotavirus diarrhea among children under five years old in Jiangxi Province, 2009–2011. Chinese J Vaccin Immun. 2014;1:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi YL, Zhang ZQ, Hu WF, et al. Molecular epidemiological characters of viral diarrhea in infants and young children less than 5 years old in surveillance hospitals from Anhui Province, 2011–2012. Chinese J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18:508–511. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng-dong Y Analysis of the pathogen microbes in 0 to 5 years old children with acute diarrhea. J Bengbu Med Coll. 2014;8:1107–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fei Y, Sun Q, Fu YF, et al. Study on the infectious status and risk factors of virus diarrhea among children under the age of five in Pudong New Area. Chinese J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronghai LLG. Pathogenic analysis of 1607 infants with diarrhea in a hospital during 2012–2013. J Mod Med Health. 2014;14:2128–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang HM, Liu XJ, Pei YY, et al. Analysis of the group A rotavirus infection in children with diarrhea in Shenzhen. Intl J Lab Med. 2014;22:3068–3069. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu HX, Liu XF, Liu DP, et al. Analysis on economic burden evaluation and epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea among children under five years old. Chinese Prim Health Care. 2014;6:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang S, Wang YQ, Miao Y, et al. Etiology of viral diarrhea in children aged < 5 years in Beijing, 2013. Dis Surv. 2014;29:344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao QL, Yang XD, Li WM, et al. Surveillance for diarrhea caused by rotavirus in children hospital in Changchun, 2012. Dis Surv. 2014;29:615–618. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang CX, Li WM, Sun LW et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in Changchun from 2005–2013. Jilin Med J. 2014;32:7145–7146. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang-hong X, Liang-ju X, Xiao-mei D. Analysis on rotavirus infection among outpatient infant cases under 5 in Rizhao City from 2007 to 2009. Prev Med Trib. 2010;8:728–729. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jian-yang W, Xiao-qing S, Meng-lei L, et al. Surveillance result of rotavirus of babyhood acute diarrhea in Henan. J Mod Lab Med. 2008;23:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao-bo S, Fang-biao T, Hui D, et al. Study on clinical features of rotavirus diarrhea and G type serum in infants and children in Maanshan and Suzhou Area. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2005;20:208–210. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ming-xiang L Analysis of status of group A rotavirus infection in 2581 cases of infants with diarrhea. Yiayai Qianyan. 2012;2:78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hui-fang C, Ting-ting H, Yue-xian Y, et al. Etiological and epidemic characterization of viral diarrhea in children under the age of 5 years in Guangzhou City. Chinese J Dis Control Prev. 2014;4:900–902. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhi-ying X Etiology of Diarrhea in 1059 Children. Med Aesth Cosmetol. 2014;7:574–574. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang LJ, Du ZQ, Zhang Q, et al. Rotavirus surveillance data from Kunming Children’s Hospital, 1998–2001. Chinese J Epidemiol. 2004;25:396–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin Y, Huang X, Fang ZY, et al. Molecular epidemiology of virus diarrhea among infants and young children in Lanzhou. Chinese J Pract Pediatr. 2006;21:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma H, OuYang YB, Lin SX, et al. Detection and genotyping of rotavirus among children under 5 years old hospitalized with diarrhea in Tianjin. Chinese J Lab Med. 2010;33:752–755. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu JK, Zhen GD, Wang QP, et al. Analysis of group A rotavirus infection in children with acute diarrhea in western area of Shaoxing. Chinese J Health Lab Tech. 2014;7:970–971. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adhikary AK, Zhou Y, Kakizawa J, et al. Distribution of rotavirus VP4 genotype and VP7 serotype among Chinese children. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1998;40:641–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiao H, Nilsson M, Abreu ER, et al. Viral diarrhea in children in Beijing, China. J Med Virol. 1999;57:390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jian-ping X, Zhao-yin F, Jing Z, et al. Rotavirus positive rate and genotyping in children with diarrhea in Guangzhou from 1998 to 2001. Chinese J Exper Clin Virol. 2004;18:82. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang ZY, Yang H, Qi J, et al. Diversity of rotavirus strains among children with acute diarrhea in China: 1998–2000 surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1875–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li DD, Duan ZJ, Zhang Q, et al. Molecular characterization of unusual human G5P[6] rotaviruses identified in China. J Clin Virol. 2008;42: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo JY, Szeto KC, Tsang DN, et al. Changing epidemiology of rotavirus G-types circulating in Hong Kong, China. J Med Virol. 2005;75:170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiao-jie Z, Cheng-xun W, Li-wei S, et al. Survey of infants with rotavirus diarrhea in Changchun City in 2007. Chinese J Lab Diagnosis. 2009;13:1753–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang L Molecular epidemiologic characterization and clinical related data analysis of rotavirus in infants of Chongqing[D]. Chongqing Medical University. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jie G, Lin Z, Qiong H, et al. Analysis on clinical characteristics and molecular epidemiology of infantile rotavirus diarrhea. Maternal Child Health Care China. 2011;26:4758–4761. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qian L, Jin-su Z, Fen L, et al. Study on clinical characteristics and molecular epidemiology of younger than 5 years old children with diarrhea caused by rotavirus infection in Nanjing city in 2009–2010. Chinese J Pract Pediatr. 2011;26:1709–1711. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li-na R, Jian W, Ping L, et al. Analysis of rotavirus VP7G genotyping in Harbin in 2010. China Mod Med. 2012;19:150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fang ZY, Yang H, Zhang J, et al. Child rotavirus infection in association with acute gastroenteritis in two Chinese sentinel hospitals. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matthijnssens J, Bilcke J, Ciarlet M, et al. Rotavirus disease and vaccination: impact on genotype diversity. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:1303–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organization. Building rotavirus laboratory capacity to support the Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;88:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bresee J, Fang ZY, Wang B, et al. ; Asian Rotavirus Surveillance Network. First report from the Asian Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:988–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yen C, Tate JE, Hyde TB, et al. Rotavirus vaccines: current status and future considerations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1436–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Field EJ, Vally H, Grimwood K, et al. Pentavalent rotavirus vaccine and prevention of gastroenteritis hospitalizations in Australia. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e506–e512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paulke-Korinek M, Kollaritsch H, Aberle SW, et al. Sustained low hospitalization rates after four years of rotavirus mass vaccination in Austria. Vaccine. 2013;31:2686–2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]