Abstract

Fatigue is a common and distressing symptom in cancer patients and survivors. There is substantial variability in the severity and persistence of cancer-related fatigue that may be driven by individual differences in host factors, including characteristics that predate the cancer experience as well as responses to cancer and its treatment. This review examines biobehavioral risk factors linked to fatigue and the mechanisms through which they influence fatigue across the cancer continuum, with a focus on neuro-immune processes. Among psychosocial risk factors, childhood adversity is a strong and consistent predictor of cancer-related fatigue; other risk factors include history of depression, catastrophizing, lack of physical activity, and sleep disturbance, with compelling preliminary evidence for loneliness and trait anxiety. Among biological systems, initial work suggests that alterations in immune, neuroendocrine, and neural processes are associated with fatigue, though research is sparse. Identification of key risk factors and underlying mechanisms is critical for the development and deployment of targeted interventions to reduce the burden of fatigue in the growing population of cancer survivors. Given the multidimensional nature of fatigue, interventions that influence multiple systems may be most effective.

Keywords: Fatigue, Inflammation, Biobehavioral, Psychosocial, Neuro-Immune

Precis:

Neuro-immune processes play a critical role in cancer-related fatigue. This review examines biobehavioral risk factors and mechanisms for fatigue with a focus on psychological, neural, neuroendocrine, and immune processes and considers implications for treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Fatigue is widely recognized as one of the most common and distressing side effects of cancer and its treatment. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) has been defined as a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer and/or cancer treatment that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning.1 This definition nicely captures several key aspects of CRF that emerge from qualitative reports, namely that it is more pervasive and more intense than “normal” fatigue, not relieved by adequate sleep or rest, and may involve mental, physical, emotional, and motivational dimensions. In addition, cancer-related fatigue can arise suddenly and is very difficult to “push through”. As might be expected, fatigue leads to significant disruption in occupational, social, and leisure activities, impacting patients’ ability to perform daily activities and lead a “normal” life.2

Fatigue occurs across different types of cancer and treatment modalities. Fatigue may be elevated before treatment onset3 and typically increases over the course of treatment,4, 5 with 30% to 60% of patients reporting moderate to severe fatigue during treatment.6, 7 Although fatigue typically declines after treatment completion, symptoms may persist for months or even years in a subgroup of patients. Prevalence estimates vary, but reports suggest that approximately 20% of cancer survivors report persistent fatigue after curative treatment.8,9

Reports on cancer-related fatigue emerged in the 1980s, primarily in the nursing literature, followed by empirical studies documenting the prevalence of this symptom and its impact on quality of life.10 More recent work has examined the longitudinal course of fatigue, its predictors and correlates, and underlying mechanisms. The current review provides an overview of this recent work, focusing on neuro-immune mechanisms for fatigue and risk factors that contribute to fatigue before, during, and after treatment. The review is organized around a conceptual model that integrates across the multiple systems that have been implicated in cancer-related fatigue – psychological, neural, neuroendocrine, and immune – and can potentially serve as a framework and springboard for future research.

BIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS UNDERLYING CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

Fatigue is a complex symptom that involves input from various physiological systems resulting in the subjective experience of mental, physical, and/or emotional tiredness and lack of energy. Cancer and its treatment can have a profound effect on the brain and body, impacting multiple systems that may be relevant for fatigue. Indeed, a variety of biological mechanisms for cancer-related fatigue have been proposed, including anemia, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, serotonin dysregulation, alterations in cellular metabolism, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and inflammation.11 To date, the mechanism that has garnered the most empirical attention and support is inflammation. The so-called cytokine hypothesis of cancer-related fatigue is based on research showing that activation of proinflammatory cytokines in the periphery signals the brain, leading to fatigue and other behavioral changes.12 These changes have been collectively described as “sickness behavior”, reflecting their common appearance across different types of illness.

Inflammation in cancer patients can arise from multiple sources. Proinflammatory cytokines can be produced by tumor cells themselves and by surrounding stromal and immune cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment.13 In addition, common treatments for cancer, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, can induce inflammation as result of cellular damage and tissue injury. Further, inflammation can be triggered by psychological factors, including psychological stress14 associated with cancer diagnosis and treatment. Thus, it has been proposed that cancer and/or its treatment leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines which then act on the brain to provoke a sickness behavior response, including symptoms of fatigue.15–17

What is the evidence to support an association between inflammation and fatigue in the context of cancer? First, tumor-associated cytokines are associated with fatigue and other sickness behaviors in preclinical and human research.18 Further, preclinical models have demonstrated that radiation and chemotherapy can induce both inflammation and behavioral changes, though the role of specific cytokines in these pathways is variable.19, 20 In human studies, there is evidence that circulating cytokine concentrations are correlated with fatigue and other symptoms before, during, and after treatment.15, 21, 22 For example, studies have demonstrated links between inflammation and fatigue in the context of radiation therapy for early-stage breast and prostate cancer23 and head and neck cancer,24 chemotherapy for breast cancer,25 chemoradiation for gastrointestinal cancer,26 and autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma,27 among others. In addition, survivors of multiple cancer types with persistent fatigue show elevations in inflammatory markers.15 Finally, there is preliminary evidence that targeting inflammation with anti-cytokine agents may have beneficial effects on fatigue in cancer patients,28 similar to effects seen in other populations,29 providing stronger support for a causal association between inflammation and cancer-related fatigue.

Importantly, inflammation does not occur in isolation, but is closely regulated by psychological, neural, neuroendocrine, and immune processes. The state of these systems prior to cancer diagnosis and treatment influences one’s “baseline” inflammatory state as well as the inflammatory response to diagnosis and treatment. Cancer can also have a direct impact on these systems, which may further exacerbate or maintain inflammatory signaling after tumor removal and treatment completion. Of course, these systems may also have independent effects on fatigue that are not mediated by inflammation. In the following sections, we consider factors in each system that have been linked with fatigue before, during, and after cancer treatment.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

The prevailing model of CRF suggests that fatigue is induced by cancer treatment and resolves after treatment completion in the majority of patients. This model is based primarily on longitudinal studies focusing on mean levels of fatigue throughout the treatment trajectory. This work has been instrumental in documenting the prevalence and importance of fatigue, but it may mask important individual differences in response to tumor development, diagnosis, and treatment. Indeed, there is tremendous variability in the experience of fatigue at every stage of the cancer continuum that is not captured by a focus on mean levels.

Recently, investigators have begun to capture individual differences in symptom trajectories using an analytic approach that identifies subgroups of patients who show distinct patterns of change over time. This approach has been widely used to examine profiles of psychological adjustment to stress and has identified several prototypical trajectories of adjustment.30 To date, only a handful of studies of have used this approach to examine trajectories of fatigue in cancer patients. One study followed 261 breast cancer patients who completed assessments after treatment and over a 6 month follow-up and identified two distinct fatigue groups: one that reported consistently low fatigue (33%), and one that reported consistently high fatigue (67%).31 Similar results were observed in a study of 398 breast cancer patients assessed before surgery and monthly for 6 months, where 38.5% were classified as low fatigue and 61.5% were classified as high fatigue.32 Another study of 290 breast cancer patients assessed before surgery and over an 8 month follow-up also found two fatigue groups, although here the majority of women fell into the low fatigue group (79%) rather than the high fatigue group (21%).33 One study followed 77 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and identified three groups, including one with low fatigue (23%), one with transient fatigue (27%), and one with high fatigue (50%).34 Work by our group focused on the post-treatment period and conducted assessments with breast cancer survivors after treatment completion and over a 3–6 year follow-up, identifying 5 distinct trajectory groups: two with consistently low or very low fatigue, one with consistently high fatigue, one with initially high fatigue that declined over time, and one with initially low fatigue that increased slowly over time.35

These studies are interesting because they indicate that some patients experience very little fatigue, even during and immediately following cancer treatment, whereas others report elevated fatigue of short or longer duration. This shifts the question from “what causes fatigue?”, to “why are some patients more vulnerable to fatigue than others?”.

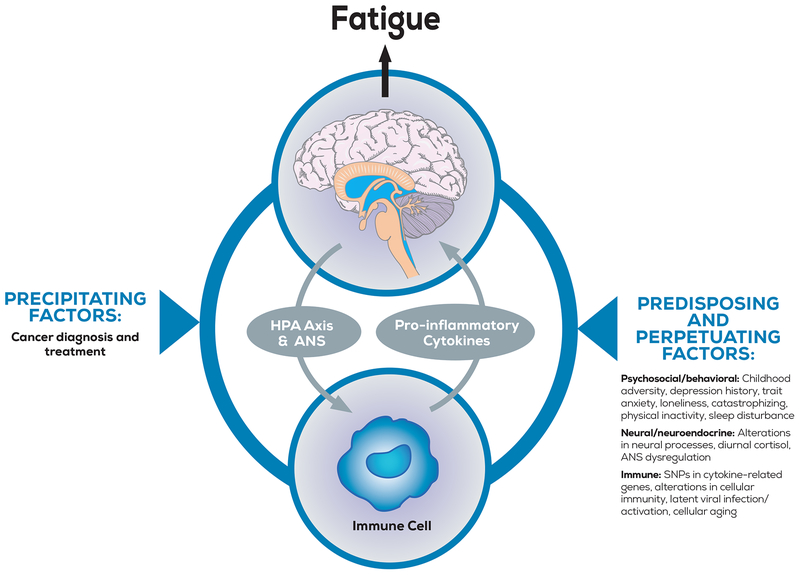

One approach to conceptualizing risk factors for cancer-related fatigue is to differentiate between predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors. Predisposing factors are enduring traits that increase an individual’s general vulnerability to develop symptoms, precipitating factors are situational conditions that trigger the onset of symptoms, and perpetuating factors contribute to the maintenance of symptoms over time. Applying this framework to the cancer context, the effects of cancer and its treatment on the body and brain are thought to be the precipitating cause of fatigue. Predisposing factors are characteristics that were present prior to the cancer experience and increase vulnerability to fatigue, whereas perpetuating factors include biological, affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to diagnosis and treatment that may influence the severity and persistence of fatigue over time. Of note, these different categories of risk factors are related; that is, predisposing factors may increase risk for fatigue by influencing more proximal perpetuating responses to diagnosis and treatment. Research on cancer-related fatigue has typically not conceptualized correlates of fatigue in this way though it may be helpful in identifying vulnerable patients as well as targets for intervention.36

Here, we consider psychosocial and biological factors that have been linked with cancer-related fatigue. Given our focus on host- rather than disease-related factors, precipitating factors (i.e., characteristics of cancer and its treatment) are not included in this review. There are enough empirical studies on psychosocial risk factors to distinguish between predisposing and perpetuating factors in that section of the review. However, the literature on biological processes is more sparse and predisposing and perpetuating factors are combined in that section. Across sections, factors linked with inflammation are of particular interest, given the importance of inflammatory processes for cancer-related fatigue.

PSYCHOSOCIAL RISK FACTORS FOR CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

Predisposing Risk Factors

Broadly defined, predisposing factors are enduring characteristics that may increase vulnerability to fatigue through effects on psychological, neural, neuroendocrine, and immune processes. Individuals with these risk factors may be fatigued before cancer; indeed, many of these risk factors have been linked with fatigue outside of the cancer context. They may also influence the response to cancer and its treatment, the regulation of that response, and/or how that response is experienced and expressed.

Childhood adversity.

Childhood adversity is unfortunately common, with more than 50% of adults reporting exposure to adverse events during childhood.37 Childhood adversity is known to predict a range of poor mental and physical health outcomes in adulthood,37 including fatigue in community dwelling adults,38, 39 and is also linked to inflammation and other neurological and neuroendocrine processes relevant for fatigue.40 Investigators have begun to examine links between exposure to various types of childhood trauma and cancer-related fatigue, primarily in breast cancer patients and survivors. Typically, studies have focused on childhood maltreatment, which includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse as well as physical and emotional neglect. However, some studies have included a broader range of childhood stressors, including conflict and chaos in the home, parental divorce, and other major life events occurring in childhood.

In a recent study of 270 women with early stage breast cancer assessed before onset of adjuvant therapy, we found that childhood trauma was the strongest and most consistent predictor of fatigue in multivariable models that included other key demographic, medical, and biological risk factors.41 Of note, 40% of the women in this study reported physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse or neglect. Longitudinal studies have yielded similar results, with higher levels of childhood adversity associated with elevated fatigue in two small studies of breast cancer patients undergoing treatment.42, 43

Studies have also examined childhood trauma and fatigue in post-treatment survivors. In an early study of 132 women who had completed treatment for breast cancer within the past 2 years, Fagundes and colleagues found that exposure to childhood maltreatment was associated with higher levels of fatigue.44 Our group used an interview-based approach to assess a range of childhood stressors in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue and found significantly higher stress exposure in the fatigued group relative to non-fatigued controls.45 Finally, we examined predictors of fatigue trajectories in 191 women with early stage breast cancer assessed for 3–6 years after cancer treatment.35 Five distinct trajectory groups were identified, including two with elevated fatigue. These groups reported higher levels of childhood adversity than the other trajectory groups, including emotional and physical abuse/neglect as well as conflict and chaos in the family.

Together, these results strongly indicate a role for childhood adversity in the experience of cancer-related fatigue before, during, and for years after treatment. There are multiple mechanisms through which childhood adversity might influence fatigue in the cancer context. First, childhood adversity is associated with low grade inflammation and an exaggerated inflammatory response to challenge,46 and could thus influence one’s baseline state and the inflammatory response to cancer diagnosis and treatment. Indeed, in a study of breast cancer patients undergoing treatment, childhood adversity was associated with elevated inflammatory activity which was in turn associated with symptoms of fatigue, suggesting a role for inflammation in the link between childhood trauma and cancer-related fatigue.43

Childhood adversity may also influence neuroendocrine systems relevant for fatigue, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system.40 Further, childhood adversity affects neural development, including alterations in threat and reward systems relevant for inflammation and other biological processes, and may also amplify signaling between the nervous and immune systems.47 In preclinical models, neonatal stress leads to long-term alterations in neuroimmune function, including chronically primed microglia that demonstrate an exaggerated response to subsequent inflammatory challenge.48 This may account in part for differences in fatigue observed in patients with the same treatment exposures but different experiences with childhood adversity. Finally, exposure to childhood adversity is known to influence affective, cognitive, and behavioral processes linked to inflammation and potentially to fatigue.46

History of depression.

History of major depressive disorder is a general risk factor for poor psychological adjustment to stress, including cancer diagnosis,49 and may also influence cancer-related fatigue. Indeed, depression and fatigue are highly correlated in cancer patients and survivors, and longitudinal studies show that depressed mood predicts elevated fatigue during and after treatment.5, 50 However, the association between these constructs is complex; fatigue is a symptom of depression, but depression can also result from the experience of fatigue.51 Here, we focus on studies that assessed past history of depression (rather than current depressed mood) to identify “predisposing factors” and clarify the temporal nature of the relationship between depression and cancer-related fatigue.

In our recent study of 270 women with early-stage breast cancer, interview-diagnosed history of major depressive disorder was associated with elevated fatigue before treatment onset, and specifically with emotional and mental dimensions of fatigue. Of note, these effects were independent of childhood adversity, although these predictors are closely related. In a longitudinal study of 288 women with early-stage breast cancer scheduled to undergo adjuvant therapy, Andrykowski and colleagues found that history of major depressive disorder predicted a diagnosis of cancer-related fatigue at post-treatment.52 History of depression was also associated with moderate to severe fatigue in a mixed sample of 515 cancer survivors,53 and predicted increases in fatigue in a mixed sample of 3032 outpatients with solid tumors assessed over a one-month period.54 However, a smaller study of 61 breast cancer survivors did not find that a history of psychiatric disorder was associated with elevated fatigue, though only 10% of the sample had a history of major depression.55 Overall, these findings suggest that history of depression may increase risk for fatigue early in the cancer trajectory, though effects on more persistent fatigue have rarely been examined.

Like childhood adversity, depression is associated with alterations in neural, neuroendocrine, psychological, behavioral, and immune processes relevant for fatigue. Even mild depressive symptoms can augment the inflammatory response to challenge,56 potentially increasing risk for fatigue. In addition, patients with a history of depression may be more likely to experience depressed mood in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis,57 with subsequent effects on fatigue.

Trait anxiety.

Relative to depression, anxiety has received little attention in research on cancer-related fatigue, perhaps because it shares less conceptual overlap with this symptom. However, the few studies that have included measures of trait anxiety have typically found positive associations with fatigue in patients and survivors.5, 9, 58–60 Trait anxiety represents a general tendency to experience anxiety and is thought to be stable over time, and is thus less likely to be influenced by cancer diagnosis and treatment than state measures. In a cross-sectional study of breast cancer survivors, trait anxiety was elevated in those with persistent cancer-related fatigue relative to non-fatigued survivors and to normal controls (who did not differ).58 Further, longitudinal assessment of these patients found that survivors with higher trait anxiety were more likely to report persistent fatigue over a 2-year follow-up period.9 In a longitudinal study of 117 breast cancer patients, trait anxiety before diagnosis predicted elevated fatigue at 6, 12, and 24 month post-surgery follow-ups.59, 60 Trait anxiety was also associated with elevated morning fatigue in breast cancer patients before and during treatment with radiation therapy.5 The mechanisms through which anxiety might influence fatigue have not been determined, but may include effects on neural and cognitive/behavioral processes. In the pain literature, catastrophizing mediates the association between anxiety and both acute and chronic pain,61 though this pathway hasn’t been examined in the context of cancer-related fatigue.

Loneliness.

Loneliness, or perceived social isolation, is a growing problem and has been linked with morbidity and mortality as well as inflammation.62, 63 There is compelling preliminary evidence that loneliness may also be relevant for cancer-related fatigue. In a cross-sectional study of 200 breast cancer survivors, loneliness was associated with higher levels of fatigue as well as pain and depression.64 Loneliness was also associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibody titers, which were in turn associated with fatigue, suggesting a role for immune dysregulation.64 Further, a longitudinal study of cancer survivors and non-cancer controls found that loneliness predicted increases in fatigue over time.65 Although we are characterizing loneliness here as a risk factor that may have predated the cancer diagnosis, it is also possible that cancer and associated symptoms, including fatigue, may precipitate feelings of social isolation;66 longitudinal research is required to disentangle these pathways.

Perpetuating Risk Factors

As noted above, predisposing factors can influence patients’ fatigue status even before cancer diagnosis, and may also influence affective, cognitive, behavioral, and biological responses to diagnosis and treatment. We consider these more proximal causes of fatigue here, focusing on cognitive and behavioral factors that have been examined in relation to cancer-related fatigue. The importance of cognitive and behavioral processes for fatigue and related symptoms has been clearly demonstrated in other areas of research, including work on chronic fatigue syndrome and pain. For example, the tendency to interpret everyday symptoms as physical in nature, negative beliefs about the experience of illness and symptoms, and an “all-or-nothing” coping response have been shown to predict chronic fatigue syndrome following viral infection.67, 68 Similarly, research on chronic pain has emphasized the importance of cognitive and emotional factors in pain persistence.69

Catastrophizing.

There is compelling evidence that illness perceptions and coping strategies play a role in fatigue in cancer patients and survivors. In particular, catastrophizing has emerged as a strong predictor of fatigue before, during, and after treatment. Catastrophizing is a cognitive process characterized by a lack of confidence and an expectation of negative outcomes. In the context of cancer-related fatigue, catastrophizing is operationalized as a maladaptive focus on fatigue, expectations that the fatigue will get worse, and perceived inability to cope with fatigue. An early longitudinal study found that breast cancer patients who endorsed more fatigue catastrophizing reported higher levels of fatigue before and at the end of radiation therapy, though catastrophizing was not related to fatigue among women receiving chemotherapy.70 In a larger group of breast cancer patients with a longer follow-up, catastrophizing emerged as one of the strongest predictors of post-treatment fatigue across treatment groups.31 These findings are consistent with cross-sectional studies showing higher levels of catastrophizing among fatigued survivors,55 and suggest that catastrophizing may play a causal role in the persistence of fatigue. Perceptions of low control over fatigue and intrusive thoughts about cancer and associated symptoms are conceptually related to catastrophizing and have also been linked with fatigue in cancer survivors.9, 71

Physical activity.

Behavioral processes are also relevant for cancer-related fatigue, particularly physical activity. Fatigue is associated with lower levels of physical activity in cross-sectional reports,72 and longitudinal studies suggest that reductions in physical activity following cancer diagnosis predict higher levels of post-treatment fatigue.52, 73 In addition, a study of fatigue trajectories found that breast cancer patients with low exercise participation at treatment completion were more likely to report elevated fatigue in the 6 months post-treatment.31 There are several pathways through which physical activity can influence fatigue. Patients who reduce activity after diagnosis and treatment may experience physical deconditioning and may also feel less confident about their ability to exercise, both of which may contribute to fatigue.74 Physical inactivity can also lead to elevated inflammation,75 with potential effects on fatigue. Fatigue may then lead to further reductions in activity,76 creating a self-perpetuating cycle. It has also been proposed that increased energy expenditure combined with decreased energy availability may lead to persistent fatigue in cancer survivors;77 this intriguing hypothesis requires evaluation in longitudinal research.

Sleep disturbance.

Sleep disturbance is common in cancer patients and survivors and is strongly correlated with fatigue.3 In longitudinal studies examining sleep as a predictor of fatigue, pre-treatment sleep disturbance was associated with elevated fatigue during treatment,5, 78 and impaired sleep at treatment completion predicted more severe fatigue in the year after treatment79 and an elevated trajectory of fatigue over a 3–6 year post-treatment follow-up.35 Of note, these longitudinal reports do not always control for concurrent fatigue, making it difficult disentangle the causal association between these symptoms. One study examined the lagged relationships among sleep, fatigue, and depression during chemotherapy and found that objective sleep disturbance (more minutes awake at night) predicted subsequent elevations in fatigue, which then predicted elevations in depressed mood.51 Sleep disruption can influence fatigue through multiple pathways, including effects on inflammatory activity.80

The relevance of cognitive and behavioral processes for fatigue in cancer survivors is supported by the success of intervention trials targeting these factors.81 Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found that cognitive behavioral therapies were the most effective type of psychological intervention for reducing cancer-related fatigue, particularly in post-treatment survivors.82 Exercise interventions designed to increase physical activity are also effective in reducing fatigue during and after treatment,82, 83 and interventions targeting insomnia have been shown to reduce fatigue in cancer survivors.84 Intervention studies can also provide clues about factors that may influence fatigue. For example, mindfulness meditation-based interventions have been shown to reduce fatigue in cancer patients and survivors,1, 85 suggesting that patients who are more “mindful” (i.e., who pay attention to present moment experiences with openness, curiosity, and lack of judgement) may be less likely to experience fatigue. Further, mindfulness, exercise, and other mind-body interventions have been shown to decrease inflammatory signaling, another potential mechanism for effects on fatigue.86

NEURO-IMMUNE PROCESSES AND CANCER-RELATED FATIGUE

This section reviews research on biological systems related to fatigue, focusing on the immune system, the neuroendocrine system, and the nervous system.

Immune system.

Alterations in the cellular immune system may drive inflammatory biology before cancer and may also influence the inflammatory response to cancer and its treatment, with potential implications for fatigue. Indeed, preclinical models demonstrate that individual differences in peripheral immune status can influence inflammatory and behavioral responses to subsequent challenge. For example, preexisting differences in leukocyte number and function predicted greater increases in IL-6 and depression-like behavior in mice exposed to social defeat stress.87 In the cancer context, studies have documented alterations in immune cell subsets and in antibody titers to latent viruses in cancer survivors with persistent fatigue,64, 88, 89 as well as genomic indicators of immune alterations (e.g., increased activation of B lymphocytes and CD8-positive T cells).90 However, it is unclear whether these alterations are a cause or consequence of fatigue, given that they were assessed in post-treatment survivors. We identified only one study that examined latent virus antibody titers in relation to fatigue before treatment in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer, which found that antibody titers to CMV (but not Epstein-Barr virus) were associated with fatigue.91 Of note, human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is associated with increased incidence of head and neck cancers and also appears to influence inflammatory activity and fatigue before and during radiation therapy.92 Polymorphisms in cytokine genes are also associated with fatigue in cancer patients and survivors and may serve as a predisposing risk factor.15, 21, 93

Cancer treatments can also influence the immune system in ways that precipitate or perpetuate fatigue. In particular, treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy can induce DNA damage and cellular senescence, both of which are considered markers of biological aging and are associated with production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.94 These effects have been documented in preclinical studies95 and recent work in humans has shown treatment effects on markers of biological aging relevant for fatigue.96, 97 Importantly, this provides a potential explanation for the persistence of elevated inflammation (and associated symptoms of fatigue) in cancer survivors after removal of the primary tumor and completion of treatment.

Although the focus here is on the peripheral immune system, which is more readily accessible in human studies, preclinical work has highlighted the important role of immune and inflammatory activity in the brain for fatigue and other cancer-related behavioral symptoms. Tumors and cancer treatments have been shown to have effects on neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory processes, including alterations in brain proinflammatory cytokines and microglia that influence neural activity and are correlated with behavioral changes in preclinical models.98 In addition, cancer treatments can influence the integrity of the blood brain barrier and potentially trafficking of peripheral immune cells to the brain, with implications for behavior.98 Of note, stress can also influence neuroimmune dynamics, including activation of microglia and peripheral immune trafficking to the brain which underlie behavioral changes in a rodent model of repeated social defeat model.99 Thus, both the psychological and physical challenges of cancer and its treatment may lead to neuroimmune alterations that influence behavior, including fatigue.

Neuroendocrine alterations.

Neuroendocrine systems, including the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, play a critical role in regulating immune and inflammatory processes100 and have been linked with fatigue outside of the cancer context (e.g., chronic fatigue syndrome101). Despite the potential relevance of these systems for cancer-related fatigue, there is a dearth of research in this area. Initial findings are promising; in particular, Lutgendorf and colleagues have documented associations between diurnal cortisol profiles and fatigue among women with ovarian cancer before diagnosis102 and in the initial months post-treatment103 that endured for up to 5 years.104 Other groups have also found alterations in diurnal cortisol and other aspects of the HPA axis in survivors with persistent fatigue,104–106 and there is recent evidence for an association between alterations in cortisol and fatigue among patients undergoing treatment.107 Dysregulation in diurnal cortisol secretion may be an indicator of circadian rhythm disturbance, which has also been implicated in cancer-related fatigue. Indeed, one study found that women with breast cancer had more disrupted circadian activity rhythms (as determined by actigraphy) and worse fatigue than healthy controls before onset of chemotherapy that worsened after treatment exposure.3 Preliminary evidence also suggests an association between autonomic dysregulation and post-treatment fatigue in cancer survivors.108, 109 However, more work is needed to determine whether dysregulation in these systems predates cancer diagnosis and treatment (and may thus be a predisposing factor for fatigue), or whether changes in these systems perpetuate fatigue or are a consequence of it.

Neural processes.

Very few neuroimaging studies in cancer patients have examined links with fatigue, focusing instead on cognitive function. However, there is growing interest in the neural processes that underlie fatigue in the context of cancer and other medical conditions, with conceptual models focusing on the anterior insula and frontostriatal network as key pathways involved in fatigue.110, 111 This work builds on research examining inflammatory mechanisms underlying depression, which has highlighted a role for the dopamine system in fatigue and other neurovegetative symptoms of depression.112

A handful of studies have examined neural processes related to fatigue in cancer patients and survivors, though methods and processes vary across reports. One cross-sectional study found an association between task-related prefrontal activation and fatigue in patients before treatment onset, and another found alterations in resting state brain connectivity in cancer survivors with persistent fatigue.113 A longitudinal study found that neural inefficiency in the executive control network at pre-treatment was associated with post-treatment fatigue,114 suggesting that alterations in neural processes may be a predisposing risk factor for fatigue. In preliminary work conducted by our group, we found that fatigue was associated with elevated amygdala reactivity in response to threatening faces, but was not associated with reward-related neural activity in breast cancer survivors.

Identifying the neural processes underlying cancer-related fatigue is an important focus for future research and has significant implications for interventions. For example, if fatigue is associated with hypervigilance and elevations in threat-related neural processes, interventions focusing on stress and anxiety-reduction might be effective; however, if fatigue is associated with disruption in dopamine and reward pathways, interventions focusing on positive affect and dopamine regulation might be more beneficial. Indeed, preliminary evidence suggests that buproprion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, may be effective in reducing cancer-related fatigue,115 and a large clinical trial was recently initiated to test this medication in fatigued breast cancer survivors. In contrast, medications targeting serotonin (i.e., paroxetine) are effective in reducing depression but not fatigue in cancer patients.116

SUMMARY AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

This review considered risk factors and mechanisms for cancer-related fatigue at multiple levels, including psychosocial, neural, neuroendocrine and immune processes involved in the initiation and maintenance of fatigue in cancer patients and survivors. A primary goal of the review was to highlight individual variability in the experience of fatigue before, during, and after treatment, and to identify factors that may contribute to fatigue at each stage of the cancer continuum. Among psychosocial risk factors, childhood adversity has emerged as a strong and consistent predictor of cancer-related fatigue; other risk factors include history of depression, catastrophizing, physical activity, and sleep disturbance, with compelling preliminary evidence for loneliness and trait anxiety. Among biological factors, polymorphisms in cytokine-related genes are associated with fatigue, and preliminary work suggests that alterations in immune, neuroendocrine, and neural processes may also play a role.

To advance our understanding of this complex symptom, longitudinal studies are needed that examine these and other key risk factors and their association with fatigue from diagnosis through survivorship. Although certain processes have received a fair amount of attention (e.g., circulating markers of inflammation), others have not (e.g., neural processes), and very few studies have integrated across systems to provide a comprehensive assessment of biobehavioral contributors to fatigue. In addition to the systems identified in this review, recent studies have highlighted other processes and systems relevant for cancer-related fatigue, including mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic disturbance, and the gut microbiome,21, 117–119 all of which interact with inflammation and merit focused attention in future research.

It is likely that different combinations of “predisposing”, “precipitating”, and “perpetuating” factors will interact to influence fatigue in a particular patient, and may have different effects on the severity and course of fatigue over time. To deal with this complexity, research on cancer-related cognitive impairment has drawn from the aging literature to identify models that describe dynamic changes in complex systems over time.120 Research on cancer-related fatigue would benefit from a consideration of similar models, such as the reliability theory of aging which helps to describe how vulnerabilities in different systems may intersect with cancer and its treatment to influence fatigue and other side effects of cancer treatment in a particular individual. Aging models may prove to be particularly helpful if fatigue is driven in part by biological aging processes.

Ultimately, the identification of key vulnerability factors and the mechanisms through which they influence fatigue will lead to the development of targeted intervention for those most in need. It is possible that there may be “subtypes” of cancer-related fatigue that are driven by different processes, similar to the idea of an inflammatory subtype of depression, and that could be used to direct interventions.121 For example, anti-cytokine therapies may be beneficial for patients with elevated inflammation,28, 122 though concerns about adverse effects limits the use of these agents in cancer patients. Pharmacologic agents could also be used to target neurotransmitter, neuroimmune, and other systems related to fatigue (e.g., buproprion, minocycline), while bright light therapy could target circadian rhythm disturbance.123 Of note, given the multidimensional nature of fatigue, interventions that influence multiple systems may be most effective. Indeed, psychosocial, exercise, and mind-body interventions appear to be more beneficial for cancer-related fatigue than pharmacotherapy,82 perhaps because these approaches have effects on a range of biobehavioral processes relevant for fatigue. The development and deployment of effective interventions is essential for reducing the burden of cancer-related fatigue and improving quality of life in the growing population of cancer survivors.

Figure 1.

The figure highlights key pathways and factors that may influence CRF based on a biobehavioral model. In this model, fatigue is precipitated (or worsened) by the effects of cancer and its treatment on the brain, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. These lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines from immune cells, which signal the brain to induce fatigue. Individual differences at each level of the model can modulate the severity and duration of this response. Predisposing factors are present before diagnosis and treatment and may increase vulnerability to CRF. potentially through effects on inflammatory processes as well as regulation of and sensitivity to those processes. Perpetuating factors include psychological/ behavioral and biologic responses to diagnosis and treatment that potentially can be targeted for intervention. ANS indicates autonomic nervous system: HPA axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: SNPs. single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Financial support:

Dr. Bower is supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF) and the National Cancer Institute (R01 5R01CA160427).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bower JE, Bak K, Berger AM, et al. Screening, Assessment and Management of Fatigue in Adult Survivors of Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation J Clin Oncol 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist 2000; 5(5): 353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ancoli-Israel S, Liu L, Rissling M, et al. Sleep, fatigue, depression, and circadian activity rhythms in women with breast cancer before and after treatment: a 1-year longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22(9): 2535–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Laronga C, Jacobsen PB. Prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2010; 116(24): 5740–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhruva A, Dodd M, Paul SM, et al. Trajectories of fatigue in patients with breast cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. Cancer Nurs 2010; 33(3): 201–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. EurJ Cancer 2002; 38(1): 27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence DP, Kupelnick B, Miller K, Devine D, Lau J. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. JNatlCancer InstMonogr 2004; (32): 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer 2006; 106(4): 751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Servaes P, Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. The course of severe fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2006; 16(9): 787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leak Bryant A, Walton AL, Phillips B. Cancer-related fatigue: scientific progress has been made in 40 years. Clinical journal of oncology nursing 2015; 19(2): 137–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell SA. Cancer-related fatigue: state of the science. PMR 2010; 2(5): 364–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. NatRevNeurosci 2008; 9(1): 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002; 420(6917): 860–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsland AL, Walsh C, Lockwood K, John-Henderson NA. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating and stimulated inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 64: 208–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue--mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2014; 11(10): 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleeland CS, Bennett GJ, Dantzer R, et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biologic mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer 2003; 97(11): 2919–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller AH, Ancoli-Israel S, Bower JE, Capuron L, Irwin MR. Neuroendocrine-immune mechanisms of behavioral comorbidities in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(6): 971–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrepf A, Lutgendorf SK, Pyter LM. Pre-treatment effects of peripheral tumors on brain and behavior: neuroinflammatory mechanisms in humans and rodents. Brain Behav Immun 2015; 49: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald TL, Hung AY, Thomas CR, Wood LJ. Localized External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) to the Pelvis Induces Systemic IL-1Beta and TNF-Alpha Production: Role of the TNF-Alpha Signaling in EBRT-Induced Fatigue. Radiation research 2016; 185(1): 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahoney SE, Davis JM, Murphy EA, McClellan JL, Gordon B, Pena MM. Effects of 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy on fatigue: role of MCP-1. Brain Behav Immun 2013; 27(1): 155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacourt TE, Heijnen CJ. Mechanisms of Neurotoxic Symptoms as a Result of Breast Cancer and Its Treatment: Considerations on the Contribution of Stress, Inflammation, and Cellular Bioenergetics. Current breast cancer reports 2017; 9(2): 70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saligan LN, Kim HS. A systematic review of the association between immunogenomic markers and cancer-related fatigue. Brain Behav Immun 2012; 26(6): 830–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Tao ML, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and fatigue during radiation therapy for breast and prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15(17): 5534–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao C, Beitler JJ, Higgins KA, et al. Fatigue is associated with inflammation in patients with head and neck cancer before and after intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 52: 145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(26): 3517–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XS, Williams LA, Krishnan S, et al. Serum sTNF-R1, IL-6, and the development of fatigue in patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemoradiation therapy. Brain BehavImmun 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang XS, Shi Q, Shah ND, et al. Inflammatory markers and development of symptom burden in patients with multiple myeloma during autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20(5): 1366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monk JP, Phillips G, Waite R, et al. Assessment of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade as an intervention to improve tolerability of dose-intensive chemotherapy in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(12): 1852–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. The Lancet 2006; 367(9504): 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonanno GA, Westphal M, Mancini AD. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual review of clinical psychology 2011; 7: 511–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donovan KA, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Munster P, Jacobsen PB. Utility of a cognitive-behavioral model to predict fatigue following breast cancer treatment. Health Psychol 2007; 26(4): 464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kober KM, Smoot B, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Polymorphisms in Cytokine Genes Are Associated With Higher Levels of Fatigue and Lower Levels of Energy in Women After Breast Cancer Surgery. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52(5): 695–708 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bodtcher H, Bidstrup PE, Andersen I, et al. Fatigue trajectories during the first 8 months after breast cancer diagnosis. Qual Life Res 2015; 24(11): 2671–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Junghaenel DU, Cohen J, Schneider S, Neerukonda AR, Broderick JE. Identification of distinct fatigue trajectories in patients with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23(9): 2579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bower JEW J; Petersen L; Irwin MR; Cole SW; Ganz PG. Fatigue after breast cancer treatment: biobehavioral predictors of fatigue trajectories. Health Psychology in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gielissen MF, Schattenberg AV, Verhagen CA, Rinkes MJ, Bremmers ME, Bleijenberg G. Experience of severe fatigue in long-term survivors of stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation 2007; 39(10): 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. AmJ PrevMed 1998; 14(4): 245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heim C, Wagner D, Maloney E, et al. Early adverse experience and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome: results from a population-based study. ArchGenPsychiatry 2006; 63(11): 1258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho HJ, Bower JE, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE, Irwin MR. Early life stress and inflammatory mechanisms of fatigue in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Brain BehavImmun 2012; 26(6): 859–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhlman KR, Chiang JJ, Horn S, Bower JE. Developmental psychoneuroendocrine and psychoneuroimmune pathways from childhood adversity to disease. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2017; 80: 166–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bower JE. Biobehavioral risk factors for cancer-related fatigue: focus on childhood maltreatment. American Psychosomatic Society; Louisville, KY; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witek JL, Tell D, Albuquerque K, Mathews HL. Childhood adversity increases vulnerability for behavioral symptoms and immune dysregulation in women with breast cancer. Brain BehavImmun 2013; 30 Suppl: S149–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han TJ, Felger JC, Lee A, Mister D, Miller AH, Torres MA. Association of childhood trauma with fatigue, depression, stress, and inflammation in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Psycho-oncology 2016; 25(2): 187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fagundes CP, Lindgren ME, Shapiro CL, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Child maltreatment and breast cancer survivors: Social support makes a difference for quality of life, fatigue and cancer stress. EurJ Cancer 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bower JE, Crosswell AD, Slavich GM. Childhood Adversity and Cumulative Life Stress: Risk Factors for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Clin PsycholSci 2014; 2(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. PsycholBull 2011; 137(6): 959–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nusslock R, Miller GE. Early-Life Adversity and Physical and Emotional Health Across the Lifespan: A Neuroimmune Network Hypothesis. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 80(1): 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 2012; 33(3): 267–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanton AL, Bower JE. Psychological Adjustment in Breast Cancer Survivors. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2015; 862: 231–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geinitz H, Zimmermann FB, Thamm R, Keller M, Busch R, Molls M. Fatigue in patients with adjuvant radiation therapy for breast cancer: long-term follow-up. JCancer ResClinOncol 2004; 130(6): 327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jim HS, Jacobsen PB, Phillips KM, Wenham RM, Roberts W, Small BJ. Lagged relationships among sleep disturbance, fatigue, and depressed mood during chemotherapy. Health Psychol 2013; 32(7): 768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andrykowski MA, Schmidt JE, Salsman JM, Beacham AO, Jacobsen PB. Use of a case definition approach to identify cancer-related fatigue in women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(27): 6613–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang XS, Zhao F, Fisch MJ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of moderate to severe fatigue: a multicenter study in cancer patients and survivors. Cancer 2014; 120(3): 425–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisch MJ, Zhao F, O’Mara AM, Wang XS, Cella D, Cleeland CS. Predictors of significant worsening of patient-reported fatigue over a 1-month timeframe in ambulatory patients with common solid tumors. Cancer 2014; 120(3): 442–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broeckel JA, Jacobsen PB, Horton J, Balducci L, Lyman GH. Characteristics and correlates of fatigue after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. JClinOncol 1998; 16(5): 1689–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Archives of general psychiatry 2003; 60(10): 1009–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jim HS, Small BJ, Minton S, Andrykowski M, Jacobsen PB. History of major depressive disorder prospectively predicts worse quality of life in women with breast cancer. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 2012; 43(3): 402–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Servaes P, Verhagen S, Bleijenberg G. Determinants of chronic fatigue in disease-free breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. AnnOncol 2002; 13(4): 589–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Vries J, Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA. Determinants of fatigue 6 and 12 months after surgery in women with early-stage breast cancer: a comparison with women with benign breast problems. J Psychosom Res 2009; 66(6): 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lockefeer JP, De Vries J. What is the relationship between trait anxiety and depressive symptoms, fatigue, and low sleep quality following breast cancer surgery? Psycho-oncology 2013; 22(5): 1127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, Gramke HF, Marcus MA. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. The Clinical journal of pain 2012; 28(9): 819–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation. Social and personality psychology compass 2014; 8(2): 58–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annual review of psychology 2015; 66: 733–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Bennett JM, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: understanding the role of immune dysregulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013; 38(8): 1310–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jaremka LM, Andridge RR, Fagundes CP, et al. Pain, depression, and fatigue: loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor. Health Psychol 2014; 33(9): 948–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deckx L, van den Akker M, van Driel M, et al. Loneliness in patients with cancer: the first year after cancer diagnosis. Psycho-oncology 2015; 24(11): 1521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moss-Morris R Symptom perceptions, illness beliefs and coping in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Mental Health 2005; 14(3): 223–35. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hulme K, Hudson JL, Rojczyk P, Little P, Moss-Morris R. Biopsychosocial risk factors of persistent fatigue after acute infection: A systematic review to inform interventions. J Psychosom Res 2017; 99: 120–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nature reviews Neuroscience 2013; 14(7): 502–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA, Thors CL. Relationship of catastrophizing to fatigue among women receiving treatment for breast cancer. JConsult ClinPsychol 2004; 72(2): 355–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dupont A, Bower JE, Stanton AL, Ganz PA. Cancer-Related Intrusive Thoughts Predict Behavioral Symptoms Following Breast Cancer Treatment. Health Psychol 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Winters-Stone KM, Bennett JA, Nail L, Schwartz A. Strength, physical activity, and age predict fatigue in older breast cancer survivors. Oncol NursForum 2008; 35(5): 815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, et al. Physical activity, long-term symptoms, and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv 2007; 1(2): 116–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Phillips SM, McAuley E. Physical activity and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a panel model examining the role of self-efficacy and depression. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2013; 22(5): 773–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elhakeem A, Murray ET, Cooper R, Kuh D, Whincup P, Hardy R. Leisure-time physical activity across adulthood and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease at age 60–64: A prospective cohort study. Atherosclerosis 2018; 269: 279–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hacker ED, Kim I, Park C, Peters T. Real-time Fatigue and Free-Living Physical Activity in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Cancer Survivors and Healthy Controls: A Preliminary Examination of the Temporal, Dynamic Relationship. Cancer nursing 2017; 40(4): 259–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lacourt TE, Vichaya EG, Chiu GS, Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ. The High Costs of Low-Grade Inflammation: Persistent Fatigue as a Consequence of Reduced Cellular-Energy Availability and Non-adaptive Energy Expenditure. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2018; 12: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smets EM, Visser MR, Willems-Groot AF, et al. Fatigue and radiotherapy: (A) experience in patients undergoing treatment. BrJCancer 1998; 78(7): 899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G. Development of fatigue in cancer survivors: a prospective follow-up study from diagnosis into the year after treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45(2): 213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Irwin MR, Opp MR. Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 42(1): 129–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, Witjes F, Bleijenberg G. Effects of cognitive behavior therapy in severely fatigued disease-free cancer patients compared with patients waiting for cognitive behavior therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(30): 4882–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, et al. Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue A Meta-analysis. Jama Oncol 2017; 3(7): 961–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. CochraneDatabaseSystRev 2012; 11: CD006145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, et al. Tai Chi Chih Compared With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Insomnia in Survivors of Breast Cancer: A Randomized, Partially Blinded, Noninferiority Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(23): 2656–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haydon MB CC; Bower JE Mindfulness interventions in breast cancer survivors: current findings and future directions. Current breast cancer reports 2018; 10(1): 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bower JE, Irwin MR. Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: A descriptive review. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 51: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hodes GE, Pfau ML, Leboeuf M, et al. Individual differences in the peripheral immune system promote resilience versus susceptibility to social stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111(45): 16136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Fahey JL, Cole SW. T-cell homeostasis in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue. JNatlCancer Inst 2003; 95(15): 1165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12(9): 2759–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Black DS, Cole SW, Christodoulou G, Figueiredo JC. Genomic mechanisms of fatigue in survivors of colorectal cancer. Cancer 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Alfano CM, et al. Fatigue and herpesvirus latency in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Brain BehavImmun 2012; 26(3): 394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xiao C, Beitler JJ, Higgins KA, et al. Associations among human papillomavirus, inflammation, and fatigue in patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer 2018; 124(15): 3163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang T, Yin J, Miller AH, Xiao C. A systematic review of the association between fatigue and genetic polymorphisms. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 62: 230–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013; 153(6): 1194–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Demaria M, O’Leary MN, Chang J, et al. Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer discovery 2017; 7(2): 165–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sanoff HK, Deal AM, Krishnamurthy J, et al. Effect of cytotoxic chemotherapy on markers of molecular age in patients with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106(4): dju057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Scuric Z, Carroll JE, Bower JE, et al. Biomarkers of aging associated with past treatments in breast cancer survivors. NPJ breast cancer 2017; 3: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Santos JC, Pyter LM. Neuroimmunology of Behavioral Comorbidities Associated With Cancer and Cancer Treatments. Frontiers in immunology 2018; 9: 1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weber MD, Godbout JP, Sheridan JF. Repeated Social Defeat, Neuroinflammation, and Behavior: Monocytes Carry the Signal. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 42(1): 46–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Irwin MR, Cole SW. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat RevImmunol 2011; 11(9): 625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cleare AJ. The neuroendocrinology of chronic fatigue syndrome. EndocrRev 2003; 24(2): 236–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weinrib AZ, Sephton SE, Degeest K, et al. Diurnal cortisol dysregulation, functional disability, and depression in women with ovarian cancer. Cancer 2010; 116(18): 4410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schrepf A, Clevenger L, Christensen D, et al. Cortisol and inflammatory processes in ovarian cancer patients following primary treatment: relationships with depression, fatigue, and disability. Brain BehavImmun 2013; 30 Suppl: S126–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cuneo MG, Schrepf A, Slavich GM, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythms, fatigue and psychosocial factors in five-year survivors of ovarian cancer. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017; 84: 139–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N. Altered cortisol response to psychologic stress in breast cancer survivors with persistent fatigue. PsychosomMed 2005; 67(2): 277–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Dickerson SS, Petersen L, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Diurnal cortisol rhythm and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005; 30(1): 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schmidt ME, Semik J, Habermann N, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM, Steindorf K. Cancer-related fatigue shows a stable association with diurnal cortisol dysregulation in breast cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 52: 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Crosswell AD, Lockwood KG, Ganz PA, Bower JE. Low heart rate variability and cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014; 45: 58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fagundes CP, Murray DM, Hwang BS, et al. Sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in cancer-related fatigue: more evidence for a physiological substrate in cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011; 36(8): 1137–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, Laye S, Capuron L. The neuroimmune basis of fatigue. Trends Neurosci 2014; 37(1): 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Karshikoff B, Sundelin T, Lasselin J. Role of Inflammation in Human Fatigue: Relevance of Multidimensional Assessments and Potential Neuronal Mechanisms. Frontiers in immunology 2017; 8: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Demetrashvili MF, et al. Basal ganglia hypermetabolism and symptoms of fatigue during interferon-alpha therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32(11): 2384–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Menning S, de Ruiter MB, Veltman DJ, et al. Multimodal MRI and cognitive function in patients with breast cancer prior to adjuvant treatment--the role of fatigue. NeuroImage Clinical 2015; 7: 547–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Askren MK, Jung M, Berman MG, et al. Neuromarkers of fatigue and cognitive complaints following chemotherapy for breast cancer: a prospective fMRI investigation. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014; 147(2): 445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ashrafi F, Mousavi S, Karimi M. Potential Role of Bupropion Sustained Release for Cancer-Related Fatigue: a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP 2018; 19(6): 1547–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Morrow GR, Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, et al. Differential effects of paroxetine on fatigue and depression: a randomized, double-blind trial from the University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program. JClinOncol 2003; 21(24): 4635–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chae JW, Chua PS, Ng T, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA content in peripheral blood with cancer-related fatigue and chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in early-stage breast cancer patients: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018; 168(3): 713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hsiao CP, Wang D, Kaushal A, Saligan L. Mitochondria-related gene expression changes are associated with fatigue in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving external beam radiation therapy. Cancer nursing 2013; 36(3): 189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jordan KR, Loman BR, Bailey MT, Pyter LM. Gut microbiota-immune-brain interactions in chemotherapy-associated behavioral comorbidities. Cancer 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ahles TA, Root JC. Cognitive Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatments. Annual review of clinical psychology 2018; 14: 425–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Miller AH, Raison CL. Are Anti-inflammatory Therapies Viable Treatments for Psychiatric Disorders?: Where the Rubber Meets the Road. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72(6): 527–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kappelmann N, Lewis G, Dantzer R, Jones PB, Khandaker GM. Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions. Mol Psychiatry 2018; 23(2): 335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Johnson JA, Garland SN, Carlson LE, et al. Bright light therapy improves cancer-related fatigue in cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice 2018; 12(2): 206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]