Abstract

Social impairment represents one of the most challenging core deficits of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and greatly affects children’s school experiences; however, few evidence-based social engagement programs have been implemented and sustained in schools. This pilot study examined the implementation and sustainment of a social engagement intervention, Remaking Recess, for four elementary-aged children with ASD and four school personnel in two urban public schools. The improved peer engagement and social network inclusion outcomes suggest that Remaking Recess can be feasibly implemented in under resourced public schools with fidelity and has the potential to improve child outcomes for children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, school-based social engagement intervention, implementation fidelity

The literature has documented the challenges that some children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience in school (Bauminger, Solomon, & Rogers, 2010; Frankel, Gorospe, Chang, & Sugar, 2011). These studies have highlighted the differences in: 1) solitary engagement and isolation on the playground (Frankel et al., 2011; Macintosh & Dissayanake, 2006; Corbett et al., 2014; Kasari et al., 2011; Locke et al., 2016); 2) inclusion in classroom social networks (Rotheram-Fuller, Chamberlain, Kasari, & Locke, 2010); 3) reciprocal friendships (Bauminger, Solomon, & Rogers, 2010); and 4) rejection (Locke, Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Kretzmann, & Jacobs, 2013) in children with ASD in comparison to their typically developing peers. While these studies have identified discrepancies in areas of social development and raise concerns about the extent to which schools are equipped to support children with ASD, they do not highlight the strengths and abilities of children with ASD. There are some children with ASD who are socially successful with peers in school settings (Locke et al., 2017); however, many children with ASD may need additional supports in school. Several interventions have shown efficacy in improving social outcomes for children with ASD in schools (Strain & Bovey, 2011; Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Locke, & Gulsrud, 2012; Kamps et al., 2014; Stahmer, Suhrheinrich, Reed, Bolduc, & Shreibman, 2011), yet few have been effectively implemented and sustained in schools (Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011). Conducting implementation research in the real-world setting can maximize the potential that study results will be more relevant to the setting, that schools will continue to use the intervention, and that its use will result in positive outcomes for students (Weisz, Chu, & Polo, 2004; Green, 2008; Green, Glasgow, Atkins, & Stange, 2009). The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the feasibility of the implementation and sustainment of Remaking Recess, a social engagement intervention, (Kretzmann, Locke, & Kasari, 2012) in two inclusive under resourced public elementary schools.

Many school-based interventions for children with ASD consist of comprehensive treatment packages that include multiple components, delivered using a variety of instructional techniques within the classroom (Arick et al., 2003; Lopata et al., 2012; Odom, Boyd, Hall, & Hume, 2010; Tucci, Hursh, Laitinen, & Lambe, 2005). These classroom-based instructional interventions, though critical for cognitive and academic development, may not effectively improve social functioning, a core deficit in ASD (Locke et al., 2014). Rather interventions that specifically target social skills and peer engagement may be needed alone and in conjunction with these practices (Bellini, Peters, Benner, & Hope, 2007; Kasari et al., 2012). However, less is known about the implementation process of social skills interventions in public schools.

Adult-facilitated and peer-mediated social skills interventions are promising evidence-based interventions to improve socialization in children with ASD (Rogers, 2000; Laushey & Heflin, 2000; Harper, Symon, & Frea, 2008; Kasari et al., 2012). Adult-facilitated intervention components may include transitioning children into a structured activity on the playground, modeling appropriate social behaviors (e.g. good sportsmanship, turn-taking, sharing, being flexible), building interpersonal communication skills, and addressing problematic and challenging social behavior (Kasari et al., 2016). In contrast, peer-mediated interventions entail training typically developing peers to interact with children with ASD (Kasari et al., 2012). Peers often are taught a series of strategies (e.g. understanding differences, using patience, redirecting, sustaining engagement, initiating, responding) that cultivate an environment of understanding, sensitivity, and acceptance that engages children with ASD. These different types of intervention strategies may be needed to address distinctive domains of social functioning in schools (i.e., playground engagement versus social network inclusion).

There are little data on the best ways to implement evidence-based interventions in schools in a way that achieves the same outcomes observed when expert, university-based interventionists implement them (Kasari et al., 2012). Evidence from other disciplines suggests that interventions often are not adopted, used, and maintained in the community in the way that they were designed (Glasgow, Vogt, & Boles, 1999). This is in part because these interventions were not developed for implementation with the barriers and constraints (e.g. number of staff, quality of training, level of expertise) that exist in most under resourced public schools (Locke et al., 2015).

Most school-based instructional programs for students with ASD are designed for teachers; however, social skills interventions can be effectively implemented by a variety of instructors including school personnel such as paraprofessionals (Licciardello, Harchik, & Luiselli, 2008). These intervention agents may be more appropriate, especially for children with ASD who are included in general education classrooms, since school personnel often directly supervise children with ASD in these settings (Robertson et al., 2003). Training school personnel who work directly with children with ASD every day to implement social skills interventions is likely to increase the generalization and maintenance of fundamental social skills for children with ASD. Yet, school personnel have not traditionally used these interventions in public schools (Rispoli, Neely, Lang, & Ganz, 2011). One intervention, Remaking Recess, combines both adult-facilitated and peer-mediated intervention strategies and has shown promising results in improving children’s social outcomes in well-resourced public schools (Kretzmann, Shih, & Kasari, 2015). The proof of concept phase in the ORBIT model for behavioral intervention development guided the methods employed in this study. The ORBIT model uses a flexible and progressive process that prespecifies clinically significant milestones and allows for iterative refinement and optimization (Czajkowski et al., 2015). Because the goal of this study was to determine whether or not Remaking Recess merits more rigorous and costly testing using a randomized controlled design, the ORBIT model suggests that a small sample size may be warranted to determine whether the treatment merits more rigorous testing (Czajkowski et al., 2015). Our study aimed to pilot test the feasibility of implementing and sustaining Remaking Recess in two under resourced public schools by measuring the fidelity of the intervention and identifying potentially important child outcomes.

Method

Participants

Four children with ASD from grades 1–5 and four school personnel from two under resourced public schools in an urban school district participated in this pilot study. The schools in which this study was carried out comprise 85% racially/ethnically diverse minorities and experience deep poverty with 70% of students who receive free/reduce lunch. Both schools had a playground; however, there was no equipment (e.g., balls, sidewalk chalk) or suitable playground structures to use. The study team provided playground equipment to ensure intervention delivery.

The average age of children with ASD was 9 (SD = 1.4) years; all were male. Two children with ASD were in second grade, one in third grade, and one in fifth grade. Three children were white and one was African American. The average IQ, as measured by the Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition (Elliott, 2007), was 88.3 (SD = 20.0). The average score on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale severity algorithm (Gotham et al., 2009) was 5.1 (SD = 3.7). Children were included if they: 1) were referred by school administrators and had a confirmed classification of ASD from an independent assessor; 2) had an IQ of 65 or higher; and 3) were included in a general education 1st-5th grade classroom for at least 80% of the school day. Children were excluded if they: 1) were not expected to stay in the school or the classroom for the duration of the study; and 2) did not have a participating school staff member who was present during their recess period.

School personnel were all female, averaged 45 years of age (SD = 8.5), and had a wide range of experience working with children with ASD (1–18 years; M = 7.8, SD = 7.3). Two school personnel were African American, one white and one identified as Other; 25% had a bachelor’s degree and 75% had an associate’s degree.

Materials and Procedure

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000).

The ADOS is a standardized clinician administered observational measure of social and communication skills used to classify children as meeting criteria for an ASD. ADOS symptom severity scores were calculated for each administration using the ADOS symptom severity algorithm (Gotham et al., 2009). All children with ASD were given the ADOS Module 3 to confirm an autism diagnosis for research participation. Data for this pilot study were gathered prior to the release of the ADOS-2.

Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition (DAS-II; Elliott, 2007).

The DAS-II is designed to assess cognitive abilities in children ages 2 years 6 months through 17 years 11 months across a broad range of developmental levels. The DAS-II yields a General Conceptual Abilities score (M = 100, SD 15) that is highly reliable, with internal consistency scores ranging from .89 to .95 and a test-retest coefficient of .90. All children with ASD were administered the DAS-II by an independent assessor to confirm eligibility.

Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE; Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, & Locke, 2005).

The POPE is a timed interval behavior coding system. Two independent observers blinded to group assignment, rated children on the playground during the lunch recess play period. Observers were trained and considered reliable with percent agreement ≥ 80. Overall, percent agreement was excellent (range 87–97%; mean = 92%). Playground engagement states were expressed as the percentage of intervals children spent in solitary engagement (i.e., unengaged with others) or alone on the playground and joint engagement with peers (i.e., playing a game, participating in a conversation or other joint activity).

Friendship Survey.

Sociometric data were gathered within each participating class to describe children’s peer groups (Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Gest, & Gariepy, 1988). Participating students were asked: “Are there kids in your class who like to hang out together? Who are they?” as a method of identifying specific children in each classroom’s social network grouping (see coding below). Children listed the names of all children in their classroom who hung out together in a group using free recall without additional prompting, class lists, or pictures. Children were reminded to include themselves in groups as well as students of both genders. Children with reading or writing difficulty were provided assistance.

Coding Social Network Inclusion (Cairns & Cairns, 1994).

Social network inclusion refers to the prominence of each individual in the overall classroom social structure. Traditional social network classifications (Cairns & Cairns, 1994) were designed to be cross-sectional measures of children’s classroom social network at one time-point. A series of social network analyses were conducted to obtain each student’s social network inclusion score following the procedures outlined by Cairns and Cairns (1994). Two related scores were calculated: 1) the student’s “individual centrality” or the total number of nominations to any peer group within the classroom; and 2) the student’s social network inclusion score. Children’s social network inclusion scores were normalized on the most nominated subject in the classroom during baseline and were calculated using children’s individual centrality at each time point divided by the highest individual centrality score within their classroom at baseline to examine the change of children’s social network inclusion over time.

Procedure

The research team met with the school district officials to obtain a list of schools with children with ASD who were included in general education classrooms. The school district nominated two under resourced schools for two reasons. First, both schools had more than one child with ASD included in general education settings, which was relatively uncommon in this particular school district as many children with ASD were primarily placed in self-contained settings regardless of ability. Second, the school district indicated that both schools needed direct training and support for their paraprofessional staff. The research team met with the principal at each prospective school and obtained a letter of agreement to participate in the study. Subsequently, recruitment materials were distributed to the schools. Ethical safeguards were in place to ensure the protection of all research participants. First, research personnel described all study activities verbally and in writing during the informed consent process. The consent form included a description of the study and expected roles and responsibilities, risks and benefits to participants, and confidentiality procedures. Research personnel clearly communicated that participation in each component of the study was completely voluntary, and participants were allowed to withdraw from the study without penalty (e.g., loss of services, etc.) at any time. All consented children with ASD in this study also provided assent as discussed below. Once families completed the consent process, recruitment materials were distributed to potential participants. Concurrently, independent assessors administered the ADOS and DAS-II to determine research eligibility. Research personnel then distributed consent forms to all children in the target child’s classroom for participation in the Friendship Survey and reviewed the purpose of the study as well as all research activities in lay language. Once informed consent from the target child’s classmates was obtained, research personnel administered an assent comprehension test to ensure children understood the study and their rights as research participants. Consented and assented children completed the Friendship Survey while blind observers recorded children’s peer engagement on the playground using the POPE and school personnel’s implementation fidelity at baseline, exit, and a 6-week follow-up. The observations did not disrupt children’s normal daily activities, and only children with ASD were observed. School personnel received $50 for their participation.

All school personnel were trained in Remaking Recess during the child’s lunch recess period (approximately 30–45 minutes) for 12 sessions over six weeks. The majority of study activities took place with participating children and school personnel outside of the classroom environment during the lunch recess period. All intervention activities were embedded into children’s daily activities, the setting in which staff were already working.

Remaking Recess

Remaking Recess is a school-based social engagement intervention for children with ASD that involves direct training and in vivo consultation with school personnel (Kretzmann, et al., 2012). All school personnel were paired with a PhD-level consultant from the research team. The training modules include the following topic areas: 1) scan and circulate the cafeteria/playground for children who may need additional support to engage with their peers; 2) identify children’s engagement states with peers; 3) follow children’s lead, strengths, and interests (engaging in activities that are motivating and of interest to the student with ASD); 4) provide developmentally and age appropriate activities and games to scaffold children’s engagement with peers; 5) support children’s social communicative behaviors (i.e., initiations and responses) and conversations with peers; 6) create opportunities to facilitate reciprocal social interaction; 7) sustain children’s engagement within an activity or game; 8) coach children through difficult situations with peers should they arise; 9) provide direct instruction on specific social engagement skills; 10) individualize the intervention to specific children in order to generalize the intervention to other students in their care; 11) work with typically developing peers to engage children with ASD; and 12) fade out of an activity/game so children learn independence (Kretzmann et al., 2015; Locke et al., 2015).

Each session took place during the child’s lunch period and targeted one didactic skill. A PhD level clinician from the research team consulted with school personnel. The consultant first explained the skill, how it applies to children with ASD, and its importance in relation to the development of children’s social functioning to school personnel. Subsequently, the consultant modeled how to use the targeted skill with children with ASD and their peers. Then, school personnel were asked to try the skill, so the consultant could provide immediate feedback. At the end of the session, school personnel were given “homework” to practice the skills during the days when the consultant was not present. Homework was reviewed at the next session.

Implementation Fidelity

Implementation fidelity, the degree to which an intervention is implemented as designed (Proctor et al., 2011), was measured using an observer-rated fidelity checklist that examined seven core components (i.e., attended to child engagement on the playground, transitioned child to an activity, facilitated activity, participated in activity, fostered communication and peer engagement, employed peer models, and provided direct instruction of social skills) of Remaking Recess. Specifically, we measured the use, whether school personnel used the intervention or not, and the quality of intervention delivery, how well they used the intervention. Use was scored “0” for “no” and “1” for “yes” to determine whether school personnel used the component of Remaking Recess. The number of components or steps were totaled and used for analysis. Quality of intervention delivery was coded on a Likert scale from “1” (not well) to “5” (very well) for each component of Remaking Recess that was used. The average quality rating across all intervention components was used for analysis. Observer-rated implementation fidelity was collected during each POPE observation. Observers were trained to percent agreement ≥ 80 on each item. Although this fidelity scale has been used in previous studies (Kretzmann et al., 2015; Locke et al., 2015), we note these data should be considered exploratory in the context of this feasibility trial.

Data Analysis

Due to the small sample size of this pilot study, statistical significance tests over time were not conducted.

Results

Table 1 presents the mean scores of social engagement outcomes at baseline, exit and follow-up.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) scores of social engagement outcomes of children with ASD

| Baseline | Exit | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social engagement outcome | Mean (SD)/Median | ||

| Playground Observation of Peer Engagement | |||

| Joint engagement | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.29 (0.08) | 0.42 (0.04) |

| Solitary engagement | 0.44 (0.42) | 0.18 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.14) |

| Social network inclusion | 0.16 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.22) | 0.13 (0.09) |

| Implementation components completed | 0.25 (0.50) | 4.00 (0.82) | 2.50 (3.32) |

| Average fidelity quality score | 0.50 (1.00) | 4.12 (1.08) | 2.20 (2.55) |

Implementation Fidelity

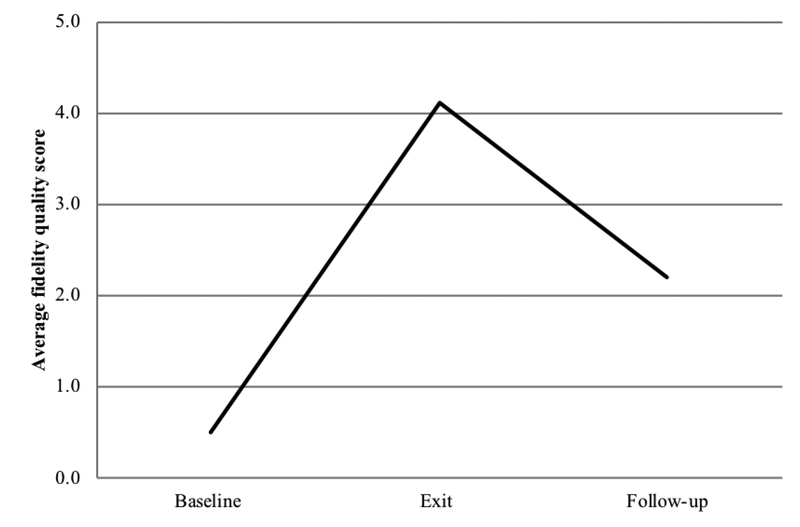

The implementation fidelity score measured by the number of completed implementation components improved immediately after training in Remaking Recess and decreased at follow-up, once consultation ended. As shown in Table 1, the fidelity score for school personnel was 0.3 at baseline and increased to 4.0 at exit, and then, decreased to 2.5 at follow-up. The average fidelity quality scores were 0.5 (SD = 1.0) at baseline, 4.1 (SD = 1.08) at exit and 2.2 (SD = 2.55) at follow-up (see Figure 1). Similar to the number of completed components, the fidelity quality scores improved significantly after the intervention and decreased at follow-up, once consultation ended.

Figure 1.

Average fidelity qualtiy score.

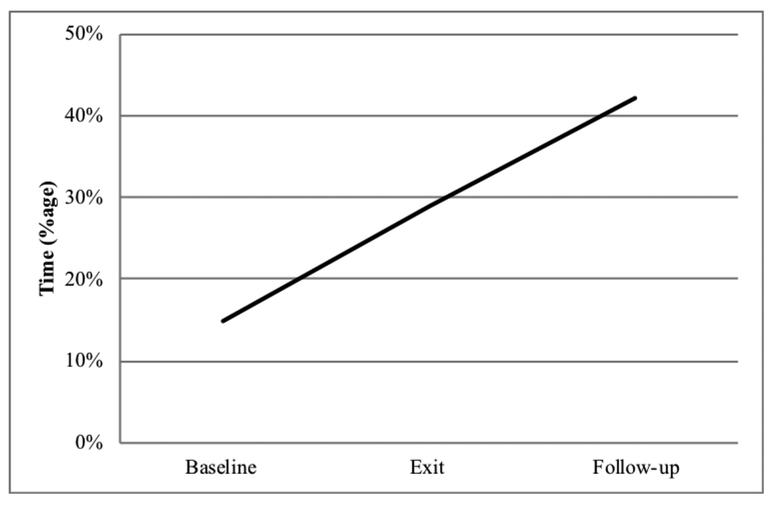

Playground Engagement

Solitary engagement on the playground decreased between baseline and exit and remained at a similar level at follow-up. The mean percentages of time spent in solitary engagement on the playground were 44% at baseline, 18% at exit and 19% follow-up. For joint engagement on the playground, the mean percentages were 15% at baseline, 29% at exit and 42% at follow-up. Joint engagement on the playground increased after the intervention and continued to increase at follow-up. Visual representations of these data are presented in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Mean percentage of time spent in solitary engagement on the playground during baseline, exit, and follow-up.

Figure 3.

Percentage of time spent in joint engagement with peers on the playground at baseline, exit, and follow-up.

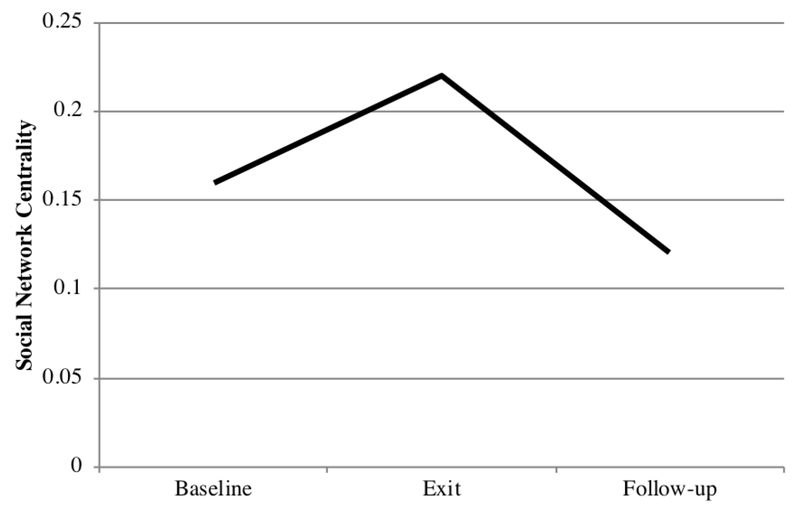

Social Network Inclusion

Figure 4 shows the visual analysis of social network inclusion. The mean score increased from 0.16 (SD = 0.11) at baseline to 0.22 (SD = 0.22) at exit and then decreased to 0.13 (SD = 0.09) at follow-up.

Figure 4.

Social network inclusion.

Discussion

This pilot study examined the use of Remaking Recess for children with ASD in general education classrooms in two under resourced public schools in a large urban city in the Northeastern United States. This study provided “proof of concept” that it is feasible for school personnel to deliver Remaking Recess in public schools. Our pilot data suggest that school personnel improved in their Remaking Recess fidelity in both use and quality of intervention delivery; however, scores decreased at the follow-up period. While these data were exploratory, the data indicate that overall implementation fidelity was low to moderate. School personnel implemented approximately half of the Remaking Recess components and were mostly accurate in their use of these strategies.

Although additional research is warranted in understanding why only half of the Remaking Recess components were accurately used, we suspect that these components were more straightforward and easier to implement for participating school personnel. Perhaps these strategies align more closely with their usual care practices. These pilot data suggest that it may be possible to train school personnel in some components of Remaking Recess more successfully than in others. Although school personnel demonstrated improvement across the six weeks of training in that they used more components (moderately well) after intervention training than they did at baseline, autism evidence-based interventions may be too difficult and complex to train school personnel to the necessary skill level that is observed in clinic or university-based settings (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011). Achieving benchmark ratings equivalent to university based and research standards may not be feasible in real-world implementation settings (Kendall & Beidas, 2007) as only 25–50% of evidence-based practices are implemented with fidelity in public schools (Cook & Odom, 2013; Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 2002). Kendall and Beidas (2007) advise that there be flexibility with fidelity to ease the implementation of a new intervention in community settings. These findings parallel previous implementation studies of autism related interventions in public schools, where implementation fidelity was much lower when the intervention was delivered in school settings, by school staff (Mandell et al., 2013; Suhrheinrich et al., 2013; Pellecchia et al., 2015; Stahmer et al., 2015; Locke et al., 2015). It is important to note that to date, relatively little is known about the factors that influence the successful use of evidence-based practices for children with ASD in under resourced public schools. There are many barriers to implementation that are exacerbated in under resourced settings that make successful implementation more challenging particularly surrounding interventions that occur at recess (Locke et al., 2015). Understanding the factors that facilitate or hinder successful implementation in these contexts may lead to more effective and targeted strategies to support the use of these interventions in real-world settings (Odom, Duda, Kucharczyk, Cox, & Stabel, 2014).

While this study informed the implementation process of Remaking Recess in schools, there also were noteworthy improvements in child outcomes. Consistent with Kretzmann and colleagues (2015), the child outcomes in this study show the potential that Remaking Recess may have in increasing joint engagement and reducing solitary engagement on the playground and improving children’s social networks. It is possible that Remaking Recess may lead to improved playground peer engagement and social network inclusion as school personnel are trained to facilitate activities and games on the playground, but future research with larger sample sizes is warranted to detect statistically different changes. Structured activities and games at recess may provide children with ASD the opportunity to learn and practice their social skills naturally that in turn, may improve peer engagement and social network inclusion. Given that social impairment is a core deficit affecting many children with ASD, future studies are warranted to dismantle the active ingredients of interventions like Remaking Recess to support children with ASD with their peers in schools. It also is noteworthy to mention that the social network inclusion scores were lower at follow-up than at exit. This pattern may suggest that ongoing consultation or training may be needed to continue school personnel’s use of Remaking Recess after external support from the research team is withdrawn. Future studies should examine this issue.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. First, although there is much to be gleaned from intervention studies of children with ASD with smaller sample sizes (Kalyva & Avramidis, 2005; Rogers et al., 2015), there were only four children with ASD and four staff members that participated in this pilot feasibility implementation study, making it difficult to conduct statistical significance tests. Second, this pilot study included only male children with ASD. Additional research on females with ASD is needed given the gender differences in socialization patterns observed between male and female children with ASD in schools (Dean et al., 2014; Dean et al., 2017). Third, it is not possible to discern whether the trends in gains children with ASD made were strictly due to inclusion in the intervention or other factors unrelated to their participation. While these data are messy, the outcome of intervention in under resourced public schools is real and warrant further research. In the United States, public schools are the most common setting for the delivery of mental health services to youth (Costello, He, Sampson, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2014; Farmer, Burns, Phillips, & Angold, 2003; Langer et al., 2015; Lyon, Ludwig, Vander Stoep, Gudmundsen, & McCauley, 2013; Merikangas et al., 2011). Therefore, it is critical that we identify the best ways in which to improve the adoption and successful implementation of evidence-based practices for children with ASD in public schools. Fourth, we note the number of measures may be excessive in this study. However, the selection of measures was purposeful and based on the extant literature that suggests peer engagement and social network inclusion are meaningful social outcomes for children with ASD in public schools (Locke et al., 2016; Kasari et al., 2011; Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010) and have been outcomes in many school-based intervention trials (Kasari et al., 2012; Kretzmann et al,. 2015; Kasari et al., 2016; Frankel et al., 2011). We also highlight that in a pilot feasibility trial, it is important to understand the potential benefits that the intervention may have on the target population (Czajkowski et al., 2015), in this case, whether Remaking Recess may improve the social outcomes of children with ASD.

Despite these limitations, there also are several notable strengths in this pilot study. First, the use of existing school personnel to implement the intervention during recess is novel and addresses a critical research to practice gap. There is some evidence that suggests it takes approximately 17 years for original research to make it into community settings (Green, Ottoson, Garcia, & Haite, 2009). In theory, training school personnel in Remaking Recess allows schools to have a cost-effective built-in mechanism to support children with ASD that also has the potential of being used school-wide to support all students during recess. Additional research is needed to test whether this is possible. Second, few studies have specifically focused on training school personnel such as classroom assistants, one-to-one assistants, and noontime aides –school staff with minimal training in autism – as intervention agents (Locke et al., 2015). This pilot study demonstrated that it was possible to train school personnel with some degree of fidelity that showed positive trends in child outcomes. These preliminary data have potential implications for the feasibility of this type of intervention for schools with limited staff resources. A third strength is the use of independent assessors to confirm research eligibility on the ADOS and DAS-II as well as blinded observers to collect child outcome data (i.e., playground engagement and social network centrality) as well as implementation fidelity to ensure data collection was unbiased.

Conclusion

This study provided “proof of concept” for Remaking Recess implementation in two under resourced public schools. Our pilot study data suggest that interventions aimed at improving social engagement for children with ASD can be successfully implemented in public school settings. Specifically, it is possible to train existing school personnel to use autism interventions in schools. These interventions can be implemented with some fidelity during naturally occurring opportunities for social interaction. Using existing school personnel as intervention agents may offset some of the barriers to implementation often observed in school settings. Short-term targeted intervention strategies, similar to the intervention used in this pilot study, may present an effective option for improving the adoption and feasibility of school-based interventions for children with ASD. Although our data are limited, they suggest an exciting path for future research investigating the implementation and effectiveness of school-based social engagement interventions for children with ASD, an important and often-overlooked area of research.

Research Involving Human Participants:

Ethical approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Autism Science Foundation (Grants # 11–1010 and #13-ECA-01L) and FARFund Early Career Award, as well as NIMH K01MH100199 (Locke). We thank the children, staff, and schools who participated and the research associates, Emily Bernabe, Margaret Mary Downey, Laura Freeman, and Rukiya Wideman, who were instrumental in data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

DR. Jill Locke, University of Washington.

Christina Kang-Yi, University of Pennsylvania.

Melanie Pellecchia, University of Pennsylvania.

David S. Mandell, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Arick J, Loos L, Falco R, & Krug D (2004). The STAR Program: Strategies for Teaching based on Autism Research. Austin, TX: PRO-ED. [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, & Rogers SJ (2010). Predicting friendship quality in autism spectrum disorders and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S, Peters JK, Benner L, Hope A. (2007). A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, & Cairns B (1994). Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Gest SD, & Gariepy JL (1988). Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology, 24, 815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Cook BG, & Odom SL (2013). Evidence-based practices and implementation science in special education. Exceptional Children, 79, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Swain DM, Newsom C, Wang L, Song Y, & Edgerton D (2014). Biobehavioral profiles of arousal and social motication in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 924–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, He J, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, & Merikangas KR (2014). Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent. Psychiatric Services, 65, 359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, ... & Epel E (2015). From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychology, 34, 971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Harwood R, & Kasari C (2017). The art of camouflage: Gender differences in the social behaviors of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21, 678–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Kasari C, Shih W, et al. (2014). The peer relationships of girls with ASD at school: Comparison to boys and girls with and without ASD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1218–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingfelder HE, & Mandell DS (2011). Bridging the research-to-practice gap in autism intervention: An application of diffusion of innovation theory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, & DuPre EP (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CD (2007). Differential Ability Scales–Second Edition (DAS-II). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Angold A, & Costello EJ (2003). Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Prevention Science, 54, 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel FD, Gorospe CM, Chang Y, & Sugar CA (2011). Mothers’ reports of play dates and observation of school playground behavior of children having high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 571–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R, Vogt T, & Boles S (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM Framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Pickles A, & Lord C (2009). Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 693–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, & Gottfredson GD (2002). Quality of school-based prevention programs: Results from a national survey. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 39, 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW (2008). Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Family Practice, 25, i20–i24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Glasgow RE, Atkins D, & Stange K (2009). Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning and practice: Slips “twixt cup and lip”. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, S187–S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Ottoson JM, Garcia C, & Hiatt RA (2009). Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 30, 151–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CB, Symon JBG, & Frea WD (2008). Recess is time-in: Using peers to improve social skills of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyva E, & Avramidis E (2005). Improving communication between children with autism and their peers through the ‘Circle of Friends’: A small-scale intervention study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 18, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps DM,Thiemann-Bourque K,Heitzman-Powell L,Schwartz I,Rosenberg N,Mason RA, and Cox S (2014).A comprehensive peer network intervention to improve social communication of children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized trial in kindergarten and first grade,Journal of Autism and Development Disorders, 45, 1809–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Dean M, & Orlich F (2016). Children with ASD and social skills groups at school: randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57,171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Locke J, Gulsrud A, & Rotheram-Fuller E (2011). Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller, & Locke J (2005). The Development of the Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE) Measure Unpublished manuscript: Los Angeles, CA: University of California Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, & Gulsrud A (2012). Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC & Beidas RS (2007). Smoothing the trail for dissemination of evidence-based practices for youth: Flexibility within fidelity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzmann M, Locke J, & Kasari C (2012). Remaking Recess: The Manual. Unpublished manuscript funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number UA3 MC 11055 (AIR-B). http://www.remakingrecess.org

- Kretzmann M, Shih W, & Kasari C (2015). Improving peer engagement of children with autism on the school playground: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 46, 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer DA, Wood JJ, Wood PA, Garland AF, Landsverk J, & Hough RL (2015). Mental health service use in schools and non-school-based outpatient settings: comparing predictors of service use. School Mental Health, 7, 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laushey KM, & Heflin LJ (2000). Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licciardello CC, Harchik AE, & Luiselli JK (2008). Social skills intervention for children with autism during interactive play at a public elementary school. Education & Treatment of Children, 31(1), 27–37. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Kretzmann M, & Jacobs J (2013). Social network changes over the school year among elementary school-aged children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. School Mental Health, 5, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Olsen A, Wideman R, Downey MM, Kretzmann M, Kasari C, & Mandell DS (2015). A tangled web: The challenges of implementing an evidence-based social engagement intervention for children with autism in urban public school settings. Behavior Therapy, 46, 54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Rotheram-Fuller E, Xie M, Harker C, & Mandell DS (2014). Correlation of cognitive and social outcomes among children with autism spectrum disorder in a randomized trial of behavioral intervention. Autism: International Journal of Research and Practice, 18, 370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Shih W, Kretzmann M, & Kasari C (2016) Examining playground engagement between elementary school children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20, 653–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Williams J, Shih W, & Kasari C (2017). Characteristics of socially successful elementary school‐aged children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata C, Thomeer ML, Volker MA, Lee GK, Smith TH, Smith RA, . . . Toomey JA (2012). Feasibility and initial efficacy of a comprehensive school‐based intervention for high‐functioning autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools, 49(10), 963–974. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. , Rutter M (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule--Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Ludwig KA, Vander Stoep A, Gudmundsen G, & McCauley E (2013). Patterns and predictors of mental healthcare utilization in schools and other service sectors among adolescents at risk for depression. School Mental Health, 5, 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh K, & Dissanayake C (2006). A comparative study of the spontaneous social interactions of children with high-functioning autism and children with Asperger’s disorder. Autism, 10, 199–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Stahmer AC, Shin S, Xie M, Reisinger E, & Marcus SC (2013). The role of treatment fidelity on outcomes during a randomized field trial of an autism intervention. Autism, 17, 281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 32–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, Boyd BA, Hall LJ, & Hume K (2010). Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, Duda MA, Kucharczyk S, Cox AW, & Stabel A (2014). Applying an implementation science framework for adoption of a comprehensive program for high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Remedial and Special Education, 35, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pellecchia M, Connell JE, Beidas RS, Xie M, Marcus SC, & Mandell DS (2015). Dismantling the active ingredients of an intervention for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi 10.1007/s10803-015-2455-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, ... & Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38, 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli M, Neely L, Lang R, & Ganz J (2011). Training paraprofessionals to implement interventions for people autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14, 378–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Chamberlain B, & Kasari C (2003). General education teachers’ relationships with included students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S (2000). Interventions that facilitate socialization in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Vismara L, Wagner AL, McCormick C, Young G, & Ozonoff S (2015). Autism treatment in the first year of life: A pilot study of infant start, a parent-implemented intervention for symptomatic infants. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2981–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram‐Fuller E, Kasari C, Chamberlain B, & Locke J (2010). Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer AC, Reed S, Lee E, Reisinger EM, Mandell DS, & Connell JE (2015). Training teachers to use evidence-based practices for autism: Examining procedural implementation fidelity. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer A, Suhrheinrich J, Reed S, Bolduc C, & Schreibman L (2011). Classroom Pivotal Response Teaching: A Guide to Effective Implementation. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strain PS, & Bovey ED (2011). Randomized, controlled trial of the LEAP model of early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31, 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Suhrheinrich J, Stahmer AC, Reed S, Schriebman L, Reisinger E, & Mandell D (2013). Implementation challenges in translating pivotal response training into community settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2970–2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci V, Hursh D, Laitinen R, & Lambe A (2005). Competent learner model for individuals with Autism/PDD. Exceptionality, 13(1), 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chu BC, & Polo AJ (2004). Treatment dissemination and evidence-based practice: Strengthening intervention through clinician-researcher collaboration. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 11, 300–307. [Google Scholar]