Abstract

Abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae are due to postoperative, spontaneous, and inflammatory etiologies. Conservative, percutaneous, endoscopic, and surgical treatment options are available options. Interventional radiologists have an array of different treatment strategies, often starting with percutaneous drainage of associated intra-abdominal abscesses. This review article details different percutaneous management strategies, focusing on percutaneous catheter strategies for abscess-fistula complexes along with tract closures strategies for enterocutaneous fistulae.

Keywords: Abscess-fistula-complex, enterocutaneous fistula, percutaneous drainage, fistula tract embolization, Crohn disease, interventional radiology

INTRODUCTION

Abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae often occur due to postoperative state or as a complication of inflammatory bowel disease and pose a difficult entity for interventional radiologists and surgeons to treat. Enterocutaneous fistulae are evident or suspected on clinical examination and supplemented by imaging. Abscess–fistula complexes are often diagnosed by catheter sinogram or computed tomography (CT) in the treatment course of percutaneous abscess drainage. Treatment is varied and includes conservative management with nutritional support, percutaneous interventions, endoscopic procedures, and surgical resection with or without surgical drainage.1–3 The purpose of this review is to describe percutaneous management strategies for abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae with a focus on the authors’ preference of a catheter- based approach.

Abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae often occur due to postoperative state or as a complication of inflammatory bowel disease and pose a difficult entity for interventional radiologists and surgeons to treat. Enterocutaneous fistulae are evident or suspected on clinical examination and supplemented by imaging. Abscess–fistula complexes are often diagnosed by catheter sinogram or computed tomography (CT) in the treatment course of percutaneous abscess drainage. Treatment is varied and includes conservative management with nutritional support, percutaneous interventions, endoscopic procedures, and surgical resection with or without surgical drainage.1–3 The purpose of this review is to describe percutaneous management strategies for abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae with a focus on the authors’ preference of a catheter- based approach.

Etiology, Demographics, and Diagnosis

Abscess–fistula complexes are intra-abdominal abscesses caused by leakage of enteral content into the abdominal cavity from a mechanical or inflammatory bowel perforation. The majority (75–85%) are postoperative or postprocedural, and the remaining are due to inflammatory or spontaneous causes, for example, inflammatory bowel disease, perforated diverticulitis or appendicitis, and necrotic tumors.1,2,4 Bowel perforation abscesses are complex collections due to the presence of viscous enteral content containing particles. The process of abscess–fistula complexes formation is often initiated from a traumatic perforation of the bowel. Causes include unrecognized intraoperative or postoperative bowel injury, perforation during minimally invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (e.g., endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), and perforation from blunt or penetrating trauma (e.g., gunshot wound). Common surgical causes include disruption of anastomosis, inadvertent enterotomy, and/or bowel puncture.1–3 After bowel perforation, the enteral content leaks into the abdominal cavity and can either spread diffusely, resulting in peritonitis, or become walled off by an anatomical compartment, forming a localized abscess. The abscess will continue to expand toward the area of least resistance, whether this is an adjacent intra-abdominal site or the surface of the overlying abdominal wall. Quite commonly, in the case of postoperative abscesses, the abdominal incision site is where these abscesses seek decompression. Enterocutaneous fistulae have a similar etiology but have direct contact with skin often apparent by leaking enteral content. Enterocutaneous fistulae will often be apparent at physical examination, either by leakage of enteral content or by skin erythema at a developing cutaneous fistula tract that has not yet broken through the skin.

Imaging diagnosis of abscess–fistula complexes is often found at follow-up catheter sinogram or CT in patients with abdominal fluid collection managed with percutaneous drainage.1,2,4 Enterocutaneous fistulae will often be suspected or diagnosed on physical examination and confirmed or demonstrated on imaging (Figure 1). Less frequently, abscess–fistula complexes or enterocutaneous fistulae may be diagnosed on screening magnetic resonance (MR) enterography (MRE) in the inflammatory bowel patient population or by diagnostic water-soluble contrast fluoroscopy studies (not related to catheter sinogram/abscessogram) (Figure 1b, c).5,6 MR or MRE can be advantageous in patients with inflammatory bowel disease to assess for abscess–fistula complexes or enterocutaneous fistulae along with active or chronic inflammation and stenosing disease.2 Advantage of CT includes the short period compared with MR and ability to see noncontiguous lesions and extraluminal pathology.2 CT should be performed with intravenous and oral contrast, unless contraindicated.

Figure 1.

Example of progression of an enterocutaneous fistula progression to an enteroatmospheric fistula. A 66-year-old male presented with multiple small bowel resections due to adhesions from prior abdominal surgery requiring surgical bowel resection, subsequently complicated by enterocutaneous fistula. Postoperatively, the patient had clinically apparent enteral content from his laparotomy incision. (a) Initial computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral but no intravenous contrast demonstrates a high attenuation tract (arrow) adjacent to contrast-containing small bowel most consistent with enterocutaneous fistula. (b,c) Cannulation of this cutaneous tract and defect with water soluble contrast injection demonstrates opacification of adjacent bowel (arrows), suggestive of enterocutaneous fistula. (d) At 3-month follow- up, the patient’s laparotomy incision dehisced, resulting in a clinically apparent enteroatmospheric fistula (e) CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous but not oral contrast demonstrates a defect of the bowel wall within a ventral hernia defect, with the sagittal reconstruction demonstrating the clinically apparent enteral content pooling in the wound’s defect (arrows).

Although CT offers better spatial resolution of small bowel compared with MR, where peristalsis often leads to elements of motion artifact (attempted to be decreased by administration of intravenous or intramuscular glucagon) and slice thickness is often thicker in MR, the better spatial resolution does not always translate into better imaging demonstration of the fistulous tract. If the fistulous tract is small and not well distended on either cross-sectional imaging modality, the signal characteristics reflecting inflammatory change and fluid on T2-weighted sequences on MR may help delineate the fistulous tract (Figure 2). The advantage and sensitivities of traditional CT with oral and intravenous contrast, CT enterography, and MR enterography have shown to be similar in small studies.2,5,6 Although the practical nature of these studies with cost and time give traditional CT examinations an advantage, cumulative radiation exposure in patients.

Figure 2.

37-year-old male with Crohn’s disease status postsubtotal colectomy with J-pouch formation complicated by proctitis flares and persistent perianal fistulas. The patient presented with new midline fecal material draining from laparotomy incision. (a–c) Precontrast (a) and postcontrast (b) T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) axial images demonstrate a midline-enhancing inflammatory tract that restricts diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (c, arrow), consistent with the known midline enterocutaneous fistula. (d–g) More caudally to the midline enterocutaneous fistula above the urinary bladder an organized collection demonstrates enhancement (precontrast T1 [d] and postcontrast T1 [e]) and diffusion restriction (f) (arrows). The collection is also delineated on precontrast coronal T2-weighted sequence (g). This is all in keeping with a postoperative abscess–fistula complex in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease.

Principles of Management

Conservative treatment for enterocutaneous fistulae and rarely abscess–fistula complexes with a diminutive abscess cavity can be managed conservatively with maximizing nutrition, keeping external wounds clean, and treating and preventing infection.3 Somatostatin is a gastrointestinal peptide hormone with an inhibitory effect on gastrointestinal secretions that is used to aid in closure of enterocutaneous fistulae. The disadvantages of this treatment are the need for intravenous administration and short half-life (minutes). Somatostatin analogues, such as octreotide and lanreotide, have been developed with longer half-lives and the ability to administer intramuscularly.7,8 Both somatostatin and somatostatin analogues have been shown in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (comparison of 234 treatment arm patients compared with 240 controls) to have significantly faster time in closure of enterocutaneous fistulae and a significantly higher proportion of fistulae closed compared with controls; no significant differences between somatostatin and somatostatin analogues were demonstrated.8 Interventional, endoscopic, or surgical approaches to enterocutaneous fistula closure are often chosen over conservative therapy, especially in patients with high output, short tract lengths, large enteric defects, or complicated fistula location. Surgical repair includes resection of the fistula with primary bowel anastomosis or fecal diversion. While surgical repair is the definitive treatment, with success rates ranging from 58 to 89%,3,9 it carries increased risk of morbidity and is often avoided, if possible, because of challenging dissections and possibility of recurrence. Interventional radiology offers effective alternatives to surgical treatment, including catheter drainage and fistula tract closure procedures. Alternatively, percutaneous strategies can bridge the patient to surgical resection by optimizing nutrition and maturing the fistulous tract. The remainder of this work will focus on percutaneous management, including the primary focus of catheter-based management, and noncatheter management strategies, including glue, plugs, and other treatments.

Catheter-Based Treatments

Catheter-based treatments are most appropriate for abscess– fistula complexes and are effective in some cases of enterocutaneous fistulae. Success rates range from 57 to 100% for resolution of abscess and fistula.1,10–16 Example cases are demonstrated in Figures 3 and 4. Various percutaneous drainage strategies have been used for more than 30 years at the time of writing. The key element in successful management of abscess–fistula complexes is aggressive and adequate drainage of the abscess cavity. Differences in various described techniques include the decision of whether or not to attempt cannulation of the fistulous tract with a drainage catheter.

Figure 3.

34-year-old morbidly obese woman presented with pelvic pain, fever, and leukocytosis. (a). Scout topogram of computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates the patient’s habitus. (b). Contrast-enhanced transaxial CT image demonstrates a large left adnexal fluid collection. This was initially managed with percutaneous drainage, which evacuated a large volume of purulent material (not pictured). (c,d) Follow-up catheter sinogram demonstrates opacification of the adjacent bowel loop (better appreciated on dynamic images) (e–g) Follow-up CT without intravenous contrast and with injection of indwelling drainage catheter demonstrates opacification of the adjacent loop of the sigmoid colon, consistent with fistulous communication.

Figure 4.

36-year-old female presented with Crohn’s disease and a history of multiple bowel resections and a chronic right lower quadrant abscess–fistula complex. (a) Initial contrast-enhanced transaxial computed tomography (CT) image demonstrates a large fluid collection; the patient was 2 weeks postoperative from an ileocecectomy. This was managed by percutaneous drainage. (b–f) On follow-up imaging, CT demonstrates that the fluid collection has resolved with an inflammatory tract about the course of the drainage catheter (b,c). Sinogram through existing catheter reveals a persistent fistulous tract to the adjacent bowel (d–f).

Drain, Cannulate, and Downsize

In abscess–fistula complexes and selected enterocutaneous fistula, the authors prefer the approach of aggressively and adequately draining fluid collections associated with the fistula often with multiple drainage catheters with interval imaging follow-up, catheter manipulations, selectively cannulating fistula based on their output or if they are recurrent, and downsizing catheters draining an abscess or cannulating the fistula. An illustrative diagram of this is shown in Figure 5. This management strategy has been effective in reported series ranging from 86 to 100% in postoperative populations1,10,11; this approach is less successful in those with inflammatory bowel disease or bowel perforations due to spontaneous or other inflammatory causes.10

Figure 5.

Steps for catheter management of abscess-fistula complexes. White arrow indicates direction of intestinal peristalsis, and black arrows depict enteric fluid leaking into the inflammatory walled-off abscess cavity. (a) Percutaneous abscess evacuation using two drainage catheters. (b) After the abscess cavity has decreased in size, a catheter is inserted in the loop of the bowel in the direction of peristalsis (white arrow) to cannulate the fistulous tract. One of the pigtail catheters draining the abscess has been removed as the cavity is resolving. As the residual abscess cavity is collapsed, the pigtail catheters are either downsized or removed. (c) By this time, there is a walled-off inflammatory tract from the intestine to the skin. The catheter cannulating the fistulous tract is removed after 48 hours of keeping it closed. (d) Abscess-fistula complex resolution.

Reproduced with permission from (1): Ballard DH, Hamidian Jahromi A, Li AY, Vea R, Ahuja C, D’Agostino HB. Abscess-Fistula Complexes: A Systematic Approach for Percutaneous Catheter Management. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:1363–1367; Elsevier, 2015.

Considerations in effective abscess drainage include identifying the shortest, safest pathway, drainage catheter selection and number, pursuing short-term interval imaging follow-up with catheter sinogram or CT, and downsizing/ removing catheters as collections decrease in size. For pathway and approach of intra-abdominal and high pelvic abscesses, the authors prefer a percutaneous transabdominal ultrasound and fluoroscopic image guidance for collections easily identified by ultrasound, with selective use of CT guidance for deeper collections or collections not well seen by ultrasound. For deep pelvic abscesses, the authors prefer transvaginal or transrectal drainage over a transgluteal approach. Catheter selection stems on the principles of flow governed by Poiseuille’s law (Qlaminar 1⁄4 ΔPπr4/8μl [Qlaminar 1⁄4 ΔPπr4/μl. Qlaminar 1⁄4 laminar flow rate; ΔP 1⁄4 change in pressures; π 1⁄4 3.14; r 1⁄4 radius; μ 1⁄4 viscosity; l 1⁄4 length]).17,18 Catheter diameter is the most important factor in achieving adequate initial abscess evacuation.18 Viscosity and change in pressure is influence by catheter flushing and selective use of suction. In larger abscesses, ≥6 cm, and those that demonstrate complexity by viscous effluent with debris or enteral content, the authors use a paired catheter approach in draining the abscess (Figure 5a).1 Many to the majority of fistula associated with a de novo abdominal abscess are diagnosed on follow-up imaging (rather than being diagnosed on the initial imaging study or at the initial percutaneous drainage), particularly with catheter sinogram.1,3

The authors cannulate high-output and recurrent fistula with standard drainage catheters and cannulate patients who may benefit from enteral nutrition through the fistulous tract (e.g., cannulating a jejunal fistula with an enteral feeding tube as a functional jejunostomy is termed fistuloclysis).1 Selection of cannulation of the fistula can be stratified using high or low 24-hour catheter output. The authors use a reference of <200 mL per day as low output and !200 mL per day as high output. Other authors use >500 mL per day as high output and may have an intermediate range.3 Similar principles to abscess–fistula drainage can be applied to fistula cannulation and downsizing. Catheters ranging from 8.5- to 14-Fr can be used to initially cannulate the tract and progressively downsized to a small diameter red rubber catheter. The decision of using the fistula tract for enteral nutrition is dependent on fistula location, with a jejunal location being ideal.

Success of Catheter Management of Abscess–Fistula Complexes and Enterocutaneous Fistula

D’Harcour et al10 presented the largest series on catheter management of enterocutaneous fistula. Their overall success rate was 81% in 147 patients, including 86% success in 111 postoperative patients with a mean treatment duration of 39 days and 67% in 36 “spontaneous fistula” patients (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease) with a mean treatment duration of 51 days. In patient selection, they use a criterion of at least 1- month failed conservative management before attempting percutaneous catheter management, which was not taken into account for their mean treatment duration. In contrast to the “drain, cannulate, and downsize” technique described earlier, D’Harcour et al10 cannulated all fistulae regardless of output, except for colonic fistulae. Young et al13 reported a series of 46 patients, primarily postoperative (67%; 31 of 46 patients) with persistent fistula after successful abscess drainage of an abscess–fistula complex. After abscess resolution with percutaneous drainage, they cannulated the fistulous tract with a latex catheter. This strategy was successful in 57% of the 46 patients with a mean treatment duration of 151 days. Ballard et al1 reported a cohort of 27 patients, all of whom were postoperative or postprocedural, with abscess– fistula complexes with a success rate of 89% and a mean treatment duration of 76 days. In that series, patients with high-output fistulae had similar treatment duration but significantly more procedures. Patients with fistulae who required cannulation had significantly longer period of treatment duration and required significantly more procedures.

Other reported series have success rates ranging from 57 to 100%.11,12,14–16

Fistula Tract Closure Treatment Strategies

If sequential catheter downsizing and repositioning is unsuccessful for enterocutaneous fistula tract closure, additional interventions may be performed, all of which involve embolizing the fistulous tract with various materials and are typically well-tolerated. Most of the patients referred for closure procedures have chronic tracts lined by granulation or fibrous tissue, as their tracts have had time to mature during other failed attempts at management. Success of tract embolization can be improved by debriding the tract wall before the injection,19 thereby removing the mature surface of the wall and encouraging healing. An assortment of abrasive tools is available for this step, such as the brush included with Cook’s fistula plugs, which can access the tract from the bowel through an endoscopic approach or percutaneously, and several off-label instruments that can be inserted from the skin surface. After debridement, the tract is irrigated with hydrogen peroxide for sanitation.

The interventional radiologist has the option of several substances for tract embolization following tract preparation. Fibrin glue, which is provided as separate solutions of fibrin and thrombin that form clot upon injection, was first introduced as a treatment for enterocutaneous fistulae in the 1990s. Fibrin glue is injected along the tract site, beginning at the mouth along the bowel wall. Avalos-González et al21 reported shorter closure time for fistula tracts treated with fibrin glue versus conservative management only. This study included esophageal, gastric, small bowel, and large bowel fistulas with output < 500 mL per day. Each subgroup demonstrated statistically significant differences in closure time favoring fibrin injection, with the exception of the large bowel subgroup, which also trended toward this conclusion. Overall closure time was 12.5 ` 14.2 days for the group treated with fibrin glue and 32.5 ` 17.9 days for the group treated with conservative management only (p < 0.001).21

Wu et al22 evaluated the efficacy and safety of autologous, plate-rich fibrin glue (PRFG) for the treatment of low-output enterocutaneous fistulae. After propensity matching to account for baseline clinical differences in the treatment groups, they found a significantly shorter closure time in those treated with PRFG (median: 8 days) versus those receiving only supportive care (median: 25 days).22 Synthetic glues have also been used for fistula tract embolization. For example, n- butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol successfully treated seven large bowel, low-output fistulae.23 Overall, glue is more effective for long-tract, low-output fistluae.24

In contrast to the glue products described earlier, there are many extracellular matrix materials that provide a biological scaffold to promote tissue growth and therefore occlude the fistula tract. Early biological plugs consisted of only collagen and are not well studied. More recently, Cook developed SurgiSIS, a material comprising decellularized porcine small intestine submucosa.25 This material is found in the Anal Fistula Plug (Cook), which allows for a bidirectional treatment approach; the proximal end of the plug may be anchored within the rectal lumen, and a snare or suture may pull the cutaneous end of the plug into position. Alternatively, a solely percutaneous approach may be employed, which would be more practical in enterocutaneous fistula cases that do not involve the anus or rectum. The Anal Fistula Plug has been shown to outperform fibrin glue in the treatment of high transsphincteric anocutaneous fistulas; in the same study, the Anal Fistula Plug offered equivalent success but was associated with less morbidity when compared with surgery.25 The Biodesign Enterocutaneous Fistula Plug (Cook), which also uses SurgiSIS, provides a simpler percutaneous approach than the Anal Fistula Plug. Six cases using Biodesign were described by Lyon et al, with a clinical success rate of 85% and a mean closure time of 2 weeks.26 It is suggested that biological plugs may be particularly useful in the treatment of high-flow fistulae.27 Figure 6 depicts a case at our institution that involved treatment of an enterocutaneous fistula with a Biodesign plug in a patient with Crohn’s disease.

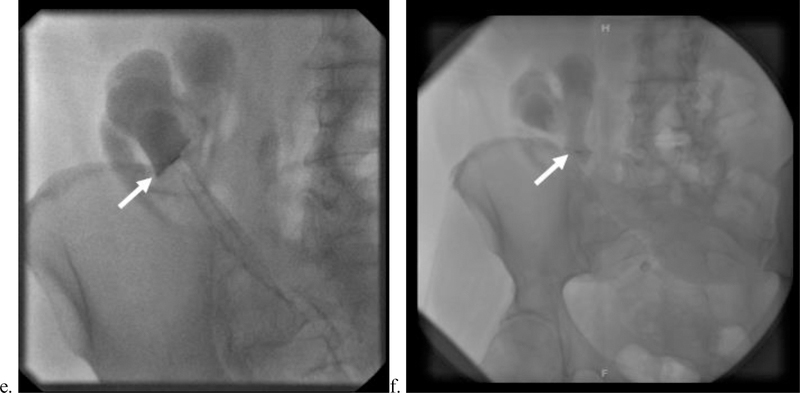

Figure 6.

53-year-old female with Crohn’s disease and a history of total abdominal colectomy (recently status: postloop ileostomy takedown and lysis of adhesions) presented with foul-smelling drainage from her surgical wound. (a,b) Transaxial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis shows a gas-filled, thickened tract extending from the inferior aspect of the patient’s surgical wound into the right lower quadrant toward a loop of the small bowel with surrounding fat stranding (arrows), consistent with an enterocutaneous fistula. (c–f) The enterocutaneous fistula was refractory to catheter drainage. Ten months after diagnosis, the patient underwent percutaneous closure of the fistula with a Biodesign plug. Part c shows a fistulous tract (yellow arrow) communicating with a loop of ileum (red arrow) in the right lower quadrant upon injection of contrast through the skin drainage site under fluoroscopy. Note the additional tract in the left lower quadrant (white arrow head) that is not in communication with bowel. Guidewire access and loading of the Biodesign plug into the fistulous tract are depicted in parts d to f. The arrows in parts e and f denote the plug device. The patient required surgical takedown of the enterocutaneous fistula and small bowel resection 2 months after this procedure.

Gelfoam (Pfizer) is a sponge containing porcine skin, gelatin, and water and has gained popularity for the purpose of hemostasis due to its ability to absorb many times its weight of blood and other fluids.28 Although it has been described as an embolic agent in the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulae,29 it is rarely used.

It is essential that multiple subspecialties are involved in the care of patients with enterocutaneous fistulae, who often are medically complicated due to active cancer, history of radiation, poor nutritional status, and sepsis. While interventional radiology is frequently indispensable in the treatment of enterocutaneous fistulae, gastroenterology can also play an important role. Many of the embolic agents described earlier can be injected through an endoscopic approach.30 Additionally, occlusion of the bowel orifice of a fistula through placement of an endoluminal covered stent may be a worthwhile palliative approach in patients who have failed other treatments or who cannot safely undergo the aforementioned procedures.30

Future Directions

There are many case reports of novel or uncommon strategies used to manage abscess–fistula complexes and enterocutaneous fistulae.31–34 With the similar reported success rates in various percutaneous approaches and even when comparing percutaneous and endoscopic management strategies to surgical approaches, the ideal approach has not been clearly defined. Emerging technologies such as three- dimensional (3D) printing may stimulate new ad hoc management strategies for patient-specific fistulae management.35,36 Huang et al35 reported the use of a novel 3D- printed patient-specific fistula stent based on reconstructing the trajectory of the patient’s enterocutaneous fistulous tract from CT data. In that case, the custom stent helped to mature the tract, bridging the patient to a fistulectomy.

Conclusions

There are a variety of percutaneous management strategies for both enterocutaneous fistulae and abscess–fistula complexes. Interventional radiologists should be aware of different options as many abscess–fistula complexes will be diagnosed in the treatment course of percutaneous management of intra- abdominal abscesses. The authors prefer a catheter strategy described earlier as a “drain, cannulate, and downsize” approach. Abscess drainage is paramount for any fistula associated with an intra-abdominal abscess. Catheter cannulation of the fistulous tract has been associated with moderate-to- good rates of tract closure. Fistula tract closure devices have also demonstrated moderate-to-good closure rates. The ideal management for enterocutaneous fistulae and abscess–fistula complexes is yet to be defined. Prospective studies comparing patients with different treatment strategies would be helpful areas of future work.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

Dr. Ballard receives salary support from National Institutes of Health TOP-TIER grant T32-EB021955.

Footnotes

Reproduce figure:

Figure 5, a figure from the authors’ previous publication has been reproduced with permission from Elsevier. This line is included with the figure legend: Reproduced with permission: Ballard DH, Hamidian Jahromi A, Li AY, Vea R, Ahuja C, D’Agostino HB. Abscess-Fistula Complexes: A Systematic Approach for Percutaneous Catheter Management. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2015; 26(9):1363-7; Elsevier, 2015.

Published in Digestive Disease Interventions as:

Ballard DH, Erickson AEM, Ahuja C, Vea R, Sangster GP, D’Agostino HB. Percutaneous Management of Enterocutaneous Fistulae and Abscess–Fistula Complexes. Digestive Disease Interventions 2018;02:131–140. DOI: 10.1055/s-0038-1660452.

References

- 1.Ballard DH,Hamidian Jahromi A,Li AY,Vea R,Ahuja C, D’Agostino HB. Abscess-fistula complexes: a systematic approach for percutaneous catheter management. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015;26(09): 1363–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JK, Stein SL. Radiographic and endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of enterocutaneous fistulas. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2010;23(03):149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman FN, Stavas JM. Interventional radiologic management and treatment of enterocutaneous fistulae. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015;26(01):7–19, quiz 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerlan RK Jr,Jeffrey RB Jr,Pogany AC,Ring EJ.Abdominalabscess with low-output fistula: successful percutaneous drainage. Radiology 1985;155(01):73–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SS, Kim AY, Yang S-K, et al. Crohn disease of the small bowel: comparison of CT enterography, MR enterography, and small- bowel follow-through as diagnostic techniques. Radiology 2009; 251(03):751–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amzallag-Bellenger E, Oudjit A, Ruiz A, Cadiot G, Soyer PA, Hoeffel CC. Effectiveness of MR enterography for the assessment of small- bowel diseases beyond Crohn disease. Radiographics 2012;32 (05):1423–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gayral F, Campion J-P, Regimbeau J-M, et al. ; Lanreotide Digestive Fistula. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy of lanreotide 30 mg PR in the treatment of pancreatic and enterocutaneous fistulae. Ann Surg 2009;250(06):872–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahbour G, Siddiqui MR, Ullah MR, Gabe SM, Warusavitarne J, Vaizey CJ. A meta-analysis of outcomes following use of somatostatin and its analogues for the management of enterocutaneous fistulas. Ann Surg 2012;256(06):946–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon SH, Oh JH, Kim HJ, Park SJ, Park HC. Interventional management of gastrointestinal fistulas. Korean J Radiol 2008;9(06):541–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Harcour JB, Boverie JH, Dondelinger RF. Percutaneous management of enterocutaneous fistulas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167 (01):33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean GK, Mackie JA, Freiman DB, Ring EJ. Enterocutaneous fistulae: interventional radiologic management. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138(04):615–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papanicolaou N, Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT Jr, et al. Abscess-fistula association: radiologic recognition and percutaneous management. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;143(04):811–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaBerge JM, Kerlan RK Jr, Gordon RL, Ring EJ. Nonoperative treatment of enteric fistulas: results in 53 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1992;3(02):353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young S, D’Souza D, Hunter D, Golzarian J, Rosenberg M. The use of latex catheters to close enterocutaneous fistulas: an institutional protocol and retrospective review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017;208 (06):1373–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AAssar OS, LaBerge JM, Gordon RL, et al. Percutaneous management of abscess and fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1999;22(01):25–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambiase RE, Cronan JJ, Dorfman GS, Paolella LP, Haas RA. Post- operative abscesses with enteric communication: percutaneous treatment. Radiology 1989;171(02):497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flancbaum L, Nosher JL, Brolin RE. Percutaneous catheter drainage of abdominal abscesses associated with perforated viscus. Am Surg 1990;56(01):52–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballard DH, Alexander JS, Weisman JA, Orchard MA, Williams JT, D’Agostino HB. Number and location of drainage catheter side holes: in vitro evaluation. Clin Radiol 2015;70(09):974–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballard DH, Flanagan ST, Li H, D’Agostino HB. In vitro evaluation of percutaneous drainage catheters: flow related to connections and liquid characteristics. Diagn Interv Imaging 2018;99(02):99–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchanan GN, Sibbons P, Osborn M, et al. Pilot study: fibrin sealant in anal fistula model. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48(03):532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avalos-González J, Portilla-deBuen E, Leal-Cortés CA, et al. Reduction of the closure time of postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas with fibrin sealant. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16(22):2793–2800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Ren J, Gu G, et al. Autologous platelet rich fibrin glue for sealing of low-output enterocutaneous fistulas: an observational cohort study. Surgery 2014;155(03):434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cambj Sapunar L, Sekovski B, Matić D, Tripković A, Grandić L, Družijanić N. Percutaneous embolization of persistent low-output enterocutaneous fistulas. Eur Radiol 2012;22(09):1991–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Melton GB. Enterocutaneous fistula: proven strategies and updates. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2016;29(02):130–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung W, Kazemi P, Ko D, et al. Anal fistula plug and fibrin glue versus conventional treatment in repair of complex anal fistulas. Am J Surg 2009;197(05):604–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyon JW, Hodde JP, Hucks D, Changkuon DI. First experience with the use of a collagen fistula plug to treat enterocutaneous fistulas. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(10):1559–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crespo Vallejo E, Martinez-Galdamez M, Del Olmo Martínez L, Crespo Brunet E, Santos Martin E. Percutaneous treatment of a duodenocutaneous high-flow fistula using a new biological plug. Diagn Interv Radiol 2015;21(03):247–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadhwa V, Leeper WR, Tamrazi A. Percutaneous BioOrganic sealing of duodenal fistulas: case report and review of biological sealants with potential use in interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2015;38(04):1036–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lisle DA, Hunter JC, Pollard CW, Borrowdale RC. Percutaneous gelfoam embolization of chronic enterocutaneous fistulas: report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50(02):251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rábago LR, Ventosa N, Castro JL, Marco J, Herrera N, Gea F. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative fistulas resistant to conservative management using biological fibrin glue. Endoscopy 2002;34(08):632–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang YJ, Oh JH, Yoon Y, et al. Covered metallic stent placement in the treatment of postoperative fistula resistant to conservative management after Billroth I operation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2005;28(01):90–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limengka Y, Jeo WS. Spontaneous closure of multiple enterocutaneous fistula due to abdominal tuberculosis using negative pressure wound therapy: a case report. J Surg Case Rep 2018; 2018(01):rjy001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musa N, Aquilino F, Panzera P, Martines G. Successful conservative treatment of enterocutaneous fistula with cyanoacrylate surgical sealant: case report. G Chir 2017;38(05):256–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasa RN, Srinivasa RN, Gemmete JJ, Hage AN, Sherk W, Chick JFB. Laser ablation facilitates closure of chronic enterocutaneous fistulae. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018;29:335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J-J, Ren J-A, Wang G-F, et al. 3D-printed “fistula stent” designed for management of enterocutaneous fistula: an advanced strategy. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23(41):7489–7494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballard DH, Trace AP, Ali S, et al. Clinical applications of 3D printing: primer for radiologists. Acad Radiol 2018;25(01):52–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]