Abstract

We explore the first period of sustained decline in child mortality in the U.S. and provide estimates of the independent and combined effects of clean water and effective sewerage systems on under-five mortality. Our case is Massachusetts, 1880 to 1920, when authorities developed a sewerage and water district in the Boston area. We find the two interventions were complementary and together account for approximately one-third of the decline in log child mortality during the 41 years. Our findings are relevant to the developing world and suggest that a piecemeal approach to infrastructure investments is unlikely to significantly improve child health.

“The interactions of water, sanitation, and hygiene with health are multiple. On the most direct level, water can be the vehicle for the transmission of a large number of pathogens. Human faeces is a frequent source of pathogens in the water and the environment … In fact, it is virtually impossible to have a safe water supply in the absence of good sanitation.”

Director-General, World Health Organization

I. Introduction

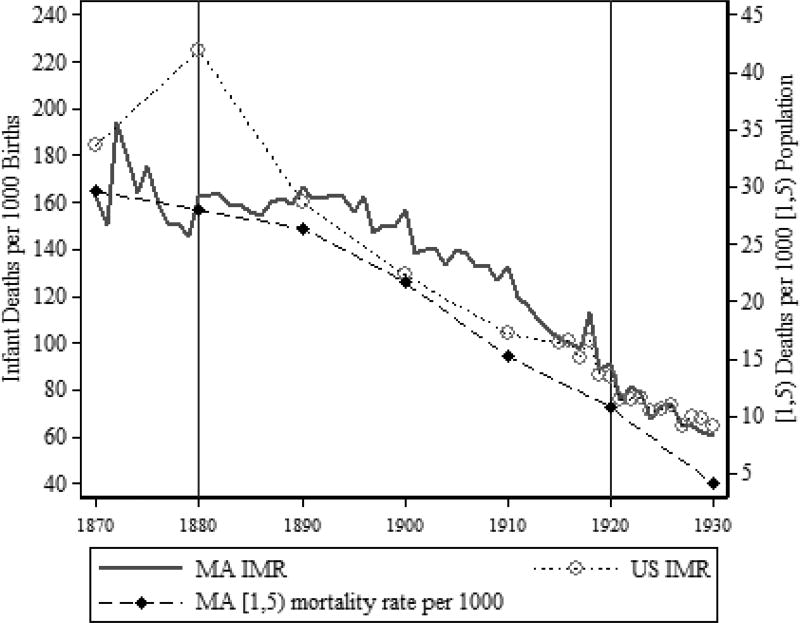

For much of the nineteenth century child mortality was the prime cause of short lifetimes at birth in the U.S. and much of Europe. In 1880 Massachusetts, for example, infant deaths were 20.4 percent of all deaths even though births were just 2.5 percent of the total population. Similarly, in 1900 infant deaths were 22.5 percent of all deaths, whereas births were 2.6 percent of the population. But change occurred swiftly and for reasons that often eluded contemporary observers and later researchers. From 1870 to 1930, life expectation conditional on reaching age 20 changed little, but infant mortality plummeted from around 1 in 5 to 1 in 16 white infants for the U.S. and Massachusetts, and deaths of non-infants under five years decreased by a factor of seven in Massachusetts (Figure 1).1 Why the rapid change?

FIGURE 1.

Infant and [1, 5) Mortality in the U.S. and Massachusetts: 1870 to 1930

Notes: The U.S. IMR series for 1850 to 1910 is probably less accurate than the Massachusetts series, which is at an annual frequency and from actual vital statistics data. See Haines (1998a) and Carter et al. (2006, p. 1–461). The right axis plots the death rate of those [1, 5) for Massachusetts based on the (yearly) registration reports and age-specific population counts from the federal decennial censuses. The U.S. aggregate series for the children [1, 5) death rate begins in 1900.

An extensive and important literature has explored the role of public health interventions in reducing the pathogenic environment of early twentieth century cities in the U.S. and Europe, and the concomitant decline of urban morbidity and mortality. Some researchers have emphasized the roles of public water and sewerage systems, whereas others have stressed additional public health factors. Analyses have been done both across and within cities. As impressive as these studies are, few can pinpoint a specific exogenous intervention. But the weight of the evidence is that cities began to clean up their acts in the early twentieth century.

Among the best identified of the research is that by Cutler and Miller (2005) on the impact of water chlorination and filtration on the death rate from waterborne diseases across 13 U.S. cities. Their estimates suggest that improved water quality accounted for 47 percent of the decline in log infant mortality from 1900 to 1936.2 In addition to purer water, effective sewerage systems were installed across many U.S. and European metropolitan areas, but their role in the mortality decline for children under five in the U.S. has yet to be rigorously assessed.3

Water and sewerage interventions interrupt different points on the fecal to oral transmission pathway. Sewerage reduces the fecal-oral transmission of pathogens by removing excrement from drinking water sources, reducing human contact with feces, and limiting exposure to the gastrointestinal diseases transmitted by flies.4 Clean water interventions remove impurities, making water safe for consumption and washing. Whether the improvements are substitutes or complements depends on their overall efficiency as well as the prevailing burden of disease. Technical complementarities between sewerage and water also existed. For instance, piped water was used to flush sewage down home drain pipes.

Our contribution to the impressive literature on public health and mortality is to provide an empirical examination, possibly the first, of the earliest sustained decline in child mortality in U.S. history. Because we use data from the state that pioneered the collection of U.S. vital statistics, our data are annual and include large and small municipalities for a period that predates national mortality statistics. Most important is that we exploit exogenous variation in both sewerage and water treatments and have information on mortality and cause of death for those under five years of age. We thus have exogenous variation in both water and sewerage treatments and examine their complementarity in the production of health using high frequency and rich mortality data.

The estimation strategy exploits a mandate originating from the Massachusetts State Board of Health that all municipalities surrounding Boston join the Metropolitan Sewerage District.5 We also rely on the fact that infrastructure rollout was based on technocratic considerations (such as the distance to various outfalls and terrain).6 Unanticipated delays further staggered the rollout, thus infrastructure completion dates were not very predictable. Because of the negative externalities associated with upstream dumping of sewage, all municipalities located within the watershed area of the Boston Harbor were compelled by law to join (and pay for) the sewerage district. Although each could elect to receive water from the Metropolitan Water District, the timing of the intervention was beyond the control of any given municipality.

Our difference-in-differences estimates show that effective sewerage and safe water systems are complements in the production of child health and their combination was a major factor contributing to the initial decline in child mortality in U.S. history. Using our preferred specification, the combination of sewerage and safe water treatments lowered child (under-five) mortality by 26.6 log points (out of a 79.2 log point decline), or 33.6 percent. The treatments lowered infant mortality by 22.8 log points (out of a 47.7 log point decline), or by 48 percent. Each intervention in isolation had a small positive health effect, but their combination caused a powerful health improvement. As the financial and political powerhouse of the Commonwealth, as well as the recipient of much of the downstream waste, Boston initiated the pure water and sewerage projects. In consequence, we exclude Boston from our analysis.

A variety of informal tests bolster our main findings about the complementarity of water and sewerage. These include: (1) that our treatment and control municipalities show minor baseline differences in infant or child mortality (also in general health determinants or in outcome variable trends prior to the interventions); (2) a sharp and persistent shift in the evolution of infant or child mortality with the introduction of the two technologies that is not as prominent with the introduction of just one; and (3) the robustness of our results to time-varying municipality-level controls and various trends.

We provide further support of a causal interpretation by examining age- and cause-specific mortality (see also Galiani, Gertler and Schargrodsky 2005). Diseases related to the gastrointestinal system and those that require fecal to oral transmission are heavily affected by the introduction of the sewerage and safe water interventions in our analysis. However, deaths from non-waterborne diseases, such as tuberculosis, or among older children and adults, are not. The age-specific result is relevant because the less than five-year-old population was most likely to succumb to gastrointestinal disease given their susceptibility to dehydration. In addition, the infrastructure improvements had larger impacts on children in municipalities that experienced more rapid population growth and had a higher fraction of certain foreign-born groups.

II. Mortality Decline and the Two Treatments: Historical Background

A. Infant and Child Mortality

Infant mortality data for the U.S. and Massachusetts start around 1850, no coincidence given the origins of U.S. vital statistics collection.7 For both series, as shown in Figure 1, the infant mortality rate (IMR) begins its long-term descent starting in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The decrease in the mortality series of children one to five years old in Massachusetts shows similar trends. We present the Massachusetts data that we construct from 1870 to 1930 because the U.S. data begin in 1900. We refer in this paper to the death rate of those less than five years as the child mortality rate (CMR).

Although the Massachusetts IMR series is highly volatile to around 1880, likely due to epidemics, the infant death rate clearly underwent a watershed event in the late 1890s. The rate fell from around 163/1,000 (1 in 6.14) in 1896 to 151/1,000 (1 in 6.62) in 1898, and then to around 91/1,000 (less than 1 in 10) by 1920.8 To understand the initial period of decline, we focus our analysis of the Massachusetts data from 1880 to 1920. What enabled more babies and children in the Commonwealth to escape death?

Several facts from the Massachusetts data provide clues regarding the cause of the initial decline in the mortality of those under five years. The first is that there was a decrease in the “urban penalty.” The initial decrease was greater in the more urbanized areas of the Commonwealth (Appendix Figure B1).9 Another clue is that whatever enabled the youngest members of society to survive apparently had little mortality impact on older individuals. Infants and young children were primarily dying of diarrheal-related illnesses, whereas adults were succumbing mainly to pulmonary tuberculosis.10

We focus on a specific group of municipalities that experienced sharp changes to their water supply and sewerage systems. These cities and towns underwent a larger decrease in both CMR and IMR than occurred in the entire Commonwealth during our analysis period, 1880 to 1920. These cities and towns also underwent a larger decrease than in comparable urban areas with no treatment. For example, CMR declined by 62 log points in our full sample of municipalities but by 79 log points in the 15 municipalities that received both treatments, compared with a 53 log point decrease in the sample that received no treatment.11

Our answer to what caused the initial decline in child mortality in Massachusetts is the radical change in water and sewage disposal and the protection of watersheds that provided purer water to the greater Boston area. An extensive public water and sewerage project created a large watershed area from which potable water could flow to homes and in which water would be protected from potentially polluting sewage that would be piped and pumped into the Boston Harbor. The area eligible to receive pure water contained more than one-third of the state’s population at the time, but included only cities and towns within a ten-mile radius of the Massachusetts State House in Boston. Even though much of the state was not directly affected by the water project, the Commonwealth in 1886 began to protect all inland waterways and to employ water engineers who aided its cities and towns.12

B. The Creation of the Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Districts

The Boston Metropolitan District had rapidly increasing population density in the post-Civil War era.13 The immediate impetus behind the creation of the Metropolitan Sewerage District (MSD) came from complaints among Boston’s wealthier citizens about the stench of sewage: “The first of a series of hearings was given by the sewerage commission at the City Hall … it would appear in various parts of the district including most of the finest streets, the stench is terrible, often causing much sickness” (Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1875, p. 79).

The sewage had two main sources. The direct outfalls from Boston dumped into the Harbor: “As early as 1870, an aggregation of old sewers discharged by about seventy outlets into tide water, chiefly along the harbor front.”14 The second was that surrounding municipalities discharged into the Mystic, Charles, and Neponset Rivers, which eventually emptied into the Harbor. Thus, Boston was the terminus for the region’s sewage. A joint engineering and medical commission was appointed in 1875 to devise a remedy.

The report of the 1875 Sewerage of Boston Commission (Chesbrough et al. 1876) recommended a drainage system for Boston and its surrounding municipalities. Boston City authorities acted and, from 1877 to 1884, constructed a comprehensive system of sewage disposal works that discharged into the deep shipping channels off Moon Island (in Quincy Bay, Boston Harbor). Attention then shifted to sources of pollution beyond its immediate control, namely the municipalities of the Neponset, Charles and Mystic River Valleys that comprised the Harbor’s immediate watershed area.15 But the obvious problems of public works coordination across municipalities complicated the control of sewage.

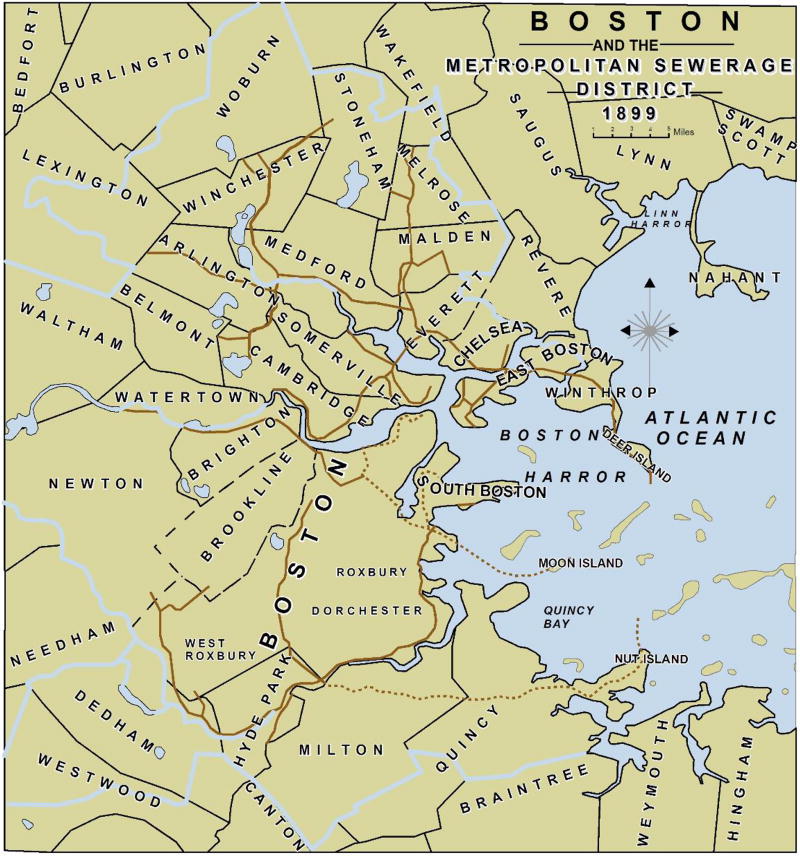

In 1887, the Boston General Court instructed the State Board of Health to revisit the regional sewerage system for the MSD. The Board was authorized to pick the included municipalities and to determine how the sewerage system would be constructed.16 The report divided the District into separate sewerage systems by geographical features. The 1889 Report (Massachusetts State Board of Health 1889) suggested an additional outfall at Deer Island (near Winthrop in Boston Harbor) draining the northern Charles River Valley and the Mystic River Valley and intercepting sewers connecting the southern portion of the Charles River Valley to the outfall on Moon Island. The Court approved recommendations by the Board to drain the Neponset River Valley with a separate outfall off Nut Island (in Quincy Bay) in 1895 (Map 1).

MAP 1.

Metropolitan Sewerage District (circa 1899)

Notes: This map depicts the Metropolitan Sewerage System circa 1899 (Source: Metropolitan Sewerage Commission of Boston, MA (1899)). The rivers draining into the Boston Harbor (from north to south) include the Mystic, Charles, and Neponset. The red solid lines depict the North and South Metropolitan Districts, the dotted lines to Moon Island trace the trajectory of the Boston sewerage system and the dotted line from Hyde Park to Nut Island demonstrates the High Level System.

As mentioned above, completion dates were determined mainly by engineering considerations. Unanticipated delays further staggered the rollout. The engineers considered the proximity of the municipalities to the harbor (which was the location of the three major outlets) as well as elevation. A Cox hazard model (Appendix Table B1) demonstrates that the timing of water and sewerage interventions was strongly affected by geographic features and not influenced significantly by pretreatment demographic characteristics of the municipality. The analysis provides further evidence that technocratic considerations, rather than immediate need, were paramount. The construction teams encountered numerous challenges, including quicksand and boulders, further delaying the completion of specific lines in an idiosyncratic manner.17

Coincidental with the construction of a regional sewerage district, Massachusetts took several steps to ensure a safe water supply. The “Act Relative to the Pollution of Rivers, Streams and Ponds Used as Sources of Water Supply,” passed in 1878, forbade persons and corporations from dumping human excrement or effluent into any pond, river or stream used as a source of water supply (Secretary of the Commonwealth 1878, p. 133). But three of the most polluted rivers—the Merrimack, Connecticut and Concord Rivers—were exempt from the law. They were heavily used by industry and manufacturers objected to their protection.

In 1886, the General Court extended the State Board of Health oversight of all inland bodies of water and directed the Board to offer advice to municipalities on water and sewerage and to employ engineers to aid the process. The Board was reorganized that year, and Hiram Mills, a hydraulic engineer, became chair of the Committee on Water Control and Sewerage. A resident of Lawrence, Mills established the Lawrence Experiment Station to test the filtration of tainted water, the first in the nation. Mills persuaded Lawrence to adopt a sand filter since its water supply was taken from the heavily polluted Merrimack River.18

In general, however, the State Board of Health eschewed filtration techniques for water purification, instead preferring that the water be derived from impounding reservoirs in which spring floodwaters were stored. The storage process clarified the water and killed off bacteria, which eventually starved or burst. The distinctive Massachusetts methods for providing pure water would soon be contrasted to those of other cities that, in the early twentieth century, began using the new filtration and chlorination techniques.

Because of the safe water strategy that Massachusetts adopted, population growth posed a serious threat to the water supply because growth inevitably led to encroachment on watersheds. The concern led to the passage of an act by the General Court in 1893 that paved the way for the creation of the Metropolitan Water District (MWD).19

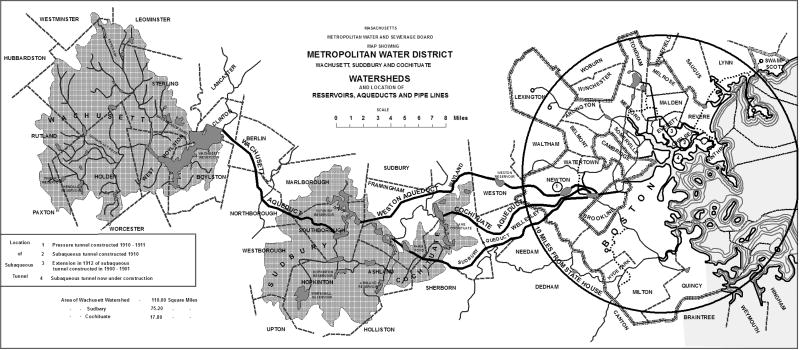

In 1895, the Board of Health recommended the creation of reservoirs in Sudbury and Wachusett by taking water from the South Branch of the Nashua River and flooding the town of West Boylston (Whipple 1917). Large aqueducts would bring fresh water to a renovated Chestnut Hill Pumping Station where it would be distributed through newly constructed iron main lines to municipalities in the MWD (Map 2). Construction on the waterworks began soon after and water started to flow to municipalities in January 1898.

MAP 2.

Metropolitan Water District (circa 1910)

Source: Engineering and Contracting (1914, p. 84).

Notes: This map depicts the Metropolitan Water District circa 1910. The circle gives the 10-mile radius from the State House that defined the eligible municipalities. Aqueducts (dark black lines) and a series of reservoirs (bodies of water labeled as such) were constructed to bring water from the south branch of the Nashua River to communities in and around Boston.

Evidence that water quality improved after the intervention comes from a report of the Metropolitan Water Board. Bacteria, fungi and other parasites were reduced from 351 per cubic centimeter in 1897 before the intervention to 192 per cubic centimeter in 1899.20 Similar observations came from the Lawrence filter. The average number of bacterial counts per cubic centimeter fell from 10,800 to 110 after filtration in 1894 (JAMA 1903). But were these interventions responsible for the initial decline in child mortality in Massachusetts?

III. Estimating Equations and Empirical Results

A. Empirical Strategy

Our empirical analysis exploits the plausibly exogenous timing and geographic penetration of safe water and sewerage interventions. We assume that child mortality in municipalities with differentially timed access to clean water and sewerage would have evolved similarly in the absence of the interventions. The validity of that assumption is assessed below.

We use a difference-in-differences framework to estimate the impact of these interventions on population health. Specifically, we estimate:

| eq. (1) |

where i is municipality and t is year. Water and Sewerage are dummy variables indicating if a municipality had adopted the safe water (Water) and/or sewerage (Sewerage) intervention by year t. The interaction of safe water and sewerage assesses whether infrastructure investments are complements or substitutes. The coefficients are difference-in-differences estimates of the impact of the interventions on the outcome, and the sum is the combined effect of the interventions, conditional on municipality and time fixed effects, municipality-specific time trends and a vector (X) of time- and municipality-varying demographic controls including (the log of) population density, percentage foreign-born, percentage male and the percentage of females employed in manufacturing. The latter variable might be important if mothers who work in factories are less likely to breastfeed and if breastfed infants are less likely to be exposed or succumb to diarrheal illness. In robustness tests, we include county-level time-varying covariates, such as dairy milk quality and a vector of dichotomous county-year fixed effects.

The main outcome of interest is the (log) under-five mortality rate, although we also explore mortality rates at other ages (under-one, under-two and over-five) and cause-specific mortality rates. The log outcome is preferred since a linear-in-levels specification constrains the mortality rate to decrease by the same amount each year across municipalities. Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level throughout the analysis since the water and sewerage treatments were at the municipality level. There are 60 clusters in our main analysis sample and we describe their selection below.

The results from our analysis of eq. (1) will show that the combination of safe water and sewage removal was an effective intervention for reducing child mortality. Each intervention separately had much smaller effects. We augment the main estimating equation by including a series of leads and lags:

| eq. (2) |

where k is event time and spans the entire range of our 41-year analysis period. We group event time into two-year bins surrounding the year immediately prior to the intervention.21 That is, we include dummy variables for whether the sewerage, water, or their interaction (meaning both sewerage and water) will take effect in (or have been in effect for) 0 to 1 years, 2 to 3 years, and so on. Leads and lags before and after nine years are coded as separate groups. The two-year bins improve the precision of the estimates by increasing the number of observations used to estimate the lead and lag coefficients.

The intervention municipalities are represented in both the pre- and post-intervention period and the analysis period is well balanced in terms of the number of treatment and control observations for all event years except the two extreme tails.22 The coefficients from eq. (2) give the dynamic response to the introduction of safe water and sewerage, and their combination.23

B. Intervention Dates and Sources

The dates of water and sewerage interventions are crucial to our empirical strategy. The treatment dates we use are when the main water and sewerage lines were completed for a given municipality rather than when homes and areas were linked to the system. In the case of water, the two dates were largely coterminous. But that was not the case for sewerage, which we will also soon discuss. The strategy we use circumvents various endogeneity concerns, and it is supported by our event studies demonstrating that the effects of only water or sewerage did not have significant lagged effects.

We obtained the intervention dates mainly from annual reports of the State Board of Health, the Metropolitan Sewerage Commission, the Metropolitan Water District (MWD) and the Metropolitan Water and Sewerage Board. We code a municipality as treated if a main sewerage or water pipe was linked to the municipality from the Metropolitan System or if a local innovation was adopted at the request and expense of the Board of Health (see Appendix Table A1 for the dates).24

None of our control municipalities is a pure control since attempts were made to improve water and sanitation across the Commonwealth. If these efforts were successful, our estimates would be biased towards the null. But we have found limited evidence that water quality was greatly improved elsewhere except for Lawrence, which is part of the treatment group. Another instance was Springfield, which used water from the Ludlow Reservoir until 1910 when the water was deemed low quality and then switched to using the Little River.25 Control towns on the Connecticut River struggled to find clean water in other waterways and create reservoirs, but they lacked the coordination provided by the Board of Health in the Boston Metropolitan Area.

Municipality-level data on births are drawn from annual vital statistics registration reports of births, marriages, and deaths (Secretary of the Commonwealth 1870–1920).26 Although the annual reports prior to 1891 included deaths by age category for every municipality, between 1891 and 1897 the data was published at the county level only. But the cost-cutting decision was later reversed and after 1897 deaths by age were reported for all counties and cities.27

To establish a consistent measure of child mortality for our sample of municipalities during our analysis time period, we created a data set of child deaths from FamilySearch.org, which is a typescript of most information contained in the death records.28 The same death certificates and death registries at the municipality level are the basis of both the Secretary of the Commonwealth’s Reports and the FamilySearch.org compilation.29 The source includes deaths of young children for (almost) every year and for every municipality in our main sample. Stillbirths and early infant deaths were not reliably distinguished.30 In compiling births, the Secretary of Commonwealth data tried to exclude stillbirths, whereas the FamilySearch.org data does not. To harmonize the two data sources, we chose to include stillbirths in both the numerator and denominator, since the definition was fluid during our period. Therefore, we add stillbirths to the official birth data. To construct the under-five population, we subtract lagged deaths at infancy and other early ages from lagged births (Data Appendix). In our robustness tests, we normalize under-five deaths by total population (Appendix Table B4).31

We also entered cause of death and grouped causes into major disease categories (such as ailments afflicting the gastrointestinal versus the respiratory system and tuberculosis). These data allow us to probe whether deaths that a priori would be more responsive to sewerage and water interventions due to fecal-oral transmission declined more than deaths from communicable disease transmitted via alternative routes (i.e., respiratory droplets in tuberculosis). Graphs of the category of death data and deaths by age are in Appendix Figures B2 to B5.

Given the importance of clean milk for the health of babies and its role in the literature on IMR, we include data on the fraction of dairies at the municipality level that passed State Board of Health inspection.32 The policy to inspect dairies and their milk started in 1905 and lasted until 1914 when the inspection authority devolved to the municipality level. For Suffolk County, milk was transported by refrigerated trains and tested for bacteria on arrival, in transit and at stores. We define the milk market at the county level and define milk purity the percentage of dairies that passed inspection and the percentage of tested milk relatively free from bacteria.

The impact of lead water pipe materials, shown to be of importance to IMR in Clay et al. (2014), is incorporated by using a cross section from 1897 of pipe materials by municipality.33 Time-varying demographic features of municipalities, such as the percentage foreign-born, age and sex distribution, and percentage of females employed in manufacturing, are obtained from state and federal censuses, linearly interpolated every five years between censuses (Appendix A).

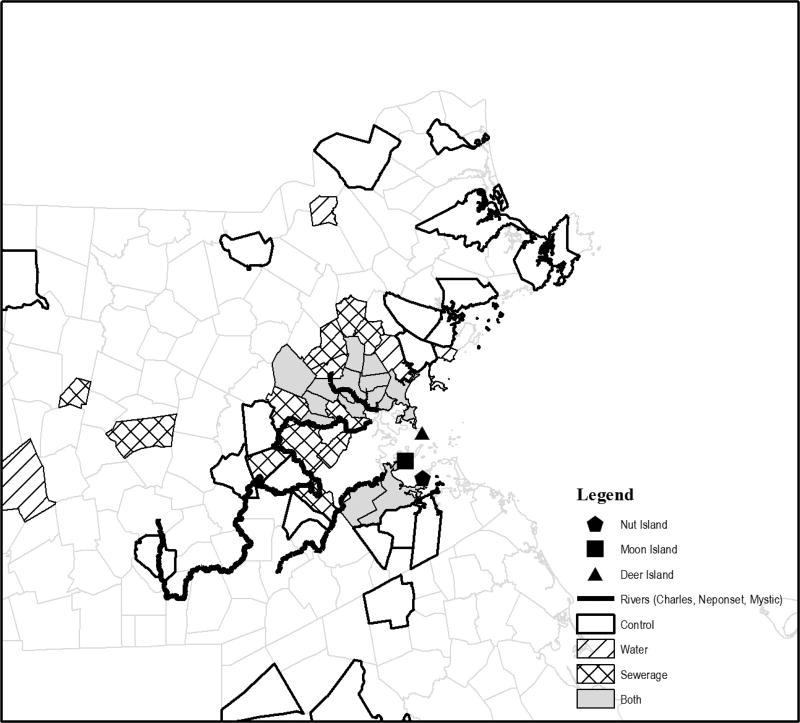

Our main sample is a panel of 60 Commonwealth municipalities (excluding Boston) from 1880 to 1920. The sample contains all municipalities within the immediate Harbor watershed area (about 12.5 miles from the Massachusetts State House) as well as municipalities outside the immediate Boston area that were incorporated cities as of 1895.34 To this list, we add two coastal municipalities (Ipswich and Weymouth) and five (Attleboro, Clinton, Milford, Natick and Peabody) with the largest 1880 populations among those that did not meet the other criteria.

In Map 3 we shade municipalities in the Boston Metropolitan Area by whether they received water (hatched), sewerage (cross-hatched), both (grey) and neither (white). Control municipalities are all in the Commonwealth since Massachusetts was unique in its early collection of detailed birth and death records. Moreover, all municipalities in the Commonwealth were exposed to other statewide Board of Health regulations, mentioned previously, that protected inland water.

MAP 3.

Safe Water and Sewerage Treatments in the Boston Metropolitan Area

C. Results

1. Main results

We first test whether there were preexisting differences in infant and child mortality, as well as other demographic variables, between municipalities that would eventually receive a safe water and sewerage treatment and those that would not. That is, we examine whether eventual participation in safe water, sewerage or both interventions is correlated with covariates in 1880 and changes in our mortality measures of interest before the interventions were formally announced.35 Table 1 presents these results.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Municipality Characteristics and Trends in Outcome Variables

| Relative to No Intervention

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All | Safe Water Only | Sewerage Only | Both Interventions | Difference (2–3) | Difference (2–4) | Difference (3–4) |

|

|

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Percentage Foreign-Born | 24.019 | 2.074 | 4.150* | −1.185 | −2.076 | 3.258 | 5.334*** |

| [8.236] | (6.344) | (2.324) | (2.157) | (6.229) | (6.168) | (1.789) | |

| Percentage Male | 47.924 | −0.320 | −0.835 | 0.210 | 0.516 | −0.529 | −1.045 |

| [2.017] | (0.906) | (0.849) | (0.620) | (1.125) | (0.964) | (0.910) | |

| Log Population Density | 0.108 | 0.689 | 0.563* | 0.437 | 0.126 | 0.252 | 0.126 |

| [0.939] | (0.606) | (0.285) | (0.326) | (0.634) | (0.654) | (0.375) | |

| Percentage Female in Manufacturing | 9.864 | 1.721 | −2.466 | −7.641*** | 4.187 | 9.362* | 5.175* |

| [7.831] | (5.456) | (3.013) | (1.721) | (5.899) | (5.356) | (2.828) | |

| Percentage Female Illiterate | 5.309 | −1.087 | 0.217 | −1.391 | −1.304 | 0.304 | 1.608* |

| [3.448] | (1.502) | (1.068) | (0.982) | (1.435) | (1.373) | (0.877) | |

| Number Neighboring Municipalities | 5.345 | −0.483 | −0.083 | −0.349 | −0.400 | −0.133 | 0.267 |

| [1.528] | (1.132) | (0.499) | (0.513) | (1.177) | (1.182) | (0.605) | |

| Log Infant Mortality Rate | 4.974 | −0.310 | −0.134 | 0.029 | −0.175 | −0.339 | −0.164* |

| [0.386] | (0.330) | (0.109) | (0.103) | (0.329) | (0.327) | (0.097) | |

| Log Under-Five Mortality Rate | 4.067 | −0.055 | −0.112 | 0.077 | 0.057 | −0.131 | −0.189* |

| [0.450] | (0.281) | (0.120) | (0.135) | (0.268) | (0.275) | (0.106) | |

| Change in Log Infant Mortality (1880–1889) | 0.151 | 0.347 | −0.014 | 0.004 | 0.361 | 0.343 | −0.018 |

| [0.429] | (0.234) | (0.164) | (0.133) | (0.262) | (0.243) | (0.178) | |

| Change in Log Under-Five Mortality (1880–1889) | 0.012 | 0.297 | 0.068 | 0.091 | 0.229 | 0.206 | −0.024 |

| [0.418] | (0.225) | (0.138) | (0.120) | (0.229) | (0.219) | (0.126) | |

Notes: Col. (1), rows (1) through (8) report average values for municipalities in 1880 with standard deviations in brackets. Cols. (2), (3) and (4) report coefficients from a single regression of the indicated characteristic in the leftmost column on an indicator variable for eventual participation in sewerage, safe water or both interventions. This categorization of the treatment differs from that in the regression analysis because the regression exploits variation across space and time, whereas this table gives the ex post treatment. The final two rows report coefficients for a similar regression, of the change in log infant mortality or child mortality between 1880 to 1889, the year of the report on a Metropolitan Sewerage District put forth by the State Board of Health as legislated in 1887, on only water, only sewerage or both in columns (1) to (4). Standard deviations are in brackets. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

The first column of Table 1 gives the mean health and demographic characteristics across the main sample. Col. (2) presents differences between municipalities that improved water without the sewerage treatment and those that did neither. Col. (3) repeats the exercise for sewerage and col. (4) gives the difference between municipalities that received both treatments versus neither. The last three columns (5 to 7) give differences between the treatment groups.

The results from rows (1) to (8) demonstrate that there are few highly significant baseline differences in demographics, the number of neighboring municipalities, and infant and child mortality across the intervention groups in 1880. Because some of the cities and towns outside the Boston metropolitan area were manufacturing hubs, the percentage of women employed in manufacturing was generally lower in the municipalities that received infrastructure interventions (Table 1, row 4) and the percentage foreign was 5.3 percentage points higher in municipalities that only received sewerage versus those that received both in the first year of the analysis (27.6 versus 22.3 percent). However, directly adding the percentage of females working in manufacturing or the percentage foreign-born as a control or dropping the untreated group from the analysis (thus using only variation in the timing of interventions) does not significantly change our estimates, suggesting that baseline differences do not bias our results.

In the last two rows, we assess for differences in infant and child mortality rates between groups of municipalities that eventually received one or more interventions using data from 1880 and 1889, the year the State Board of Health issued its report on a sewerage system for the Charles and Mystic River Valleys. Note that in the nine years prior to the interventions, the change in mortality rates was modest. In addition, whether a municipality eventually received safe water, sewerage, or both is not significantly correlated with the changing mortality pattern of young children prior to when the interventions were rolled out.

Our baseline estimates of the impact of the sewerage and water interventions, from estimating eq. (1), are presented in Table 2 Panel A for the 60 control and treatment cities and towns. The regressions are unweighted and contain municipality and year fixed effects, as well as municipality-specific linear trends and demographic controls, in every specification. By not weighting we are considering each city or town to be a separate experiment. We prefer this approach and directly model heterogeneity by population growth, a potential contaminant for the watershed areas, in Section II B (Table 3, Panel B).

TABLE 2.

The Effect of Safe Water and Sewerage on Child Mortality

| Panel A: Outcome is Log Child Mortality Rate, Main Specification |

Panel B: Outcome or Specification Varies

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOG CHILD MORTALITY | CHILD MORTALITY | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| County-Year FE | Count Model | Weighted | Unweighted | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Safe Water | −0.126 | −0.101 | 0.109 | 0.119 | 0.089 | 1.497 | 5.571 | ||

| (0.080) | (0.078) | (0.079) | (0.083) | (0.055) | (3.243) | (4.258) | |||

| Sewerage | −0.123** | −0.106** | −0.067 | −0.073 | −0.039 | −2.403 | −4.037 | ||

| (0.047) | (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.062) | (0.040) | (2.227) | (2.748) | |||

| Interaction of Safe Water and Sewerage | −0.238*** | −0.307*** | −0.298*** | −0.199** | −1.006 (3.253) | −13.498** | |||

| (0.081) | (0.106) | (0.111) | (0.079) | (3.253) | (5.102) | ||||

| −0.266*** | −0.252** | −0.149** | −1.911 | −11.963*** | |||||

| Safe Water+ Sewerage+ Interaction | p-value=0.006 | p-value=0.025 | p-value=0.029 | p-value=0.581 | p-value=0.008 | ||||

| Observations | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,440 | 2,440 | 2,440 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | County-Year | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Demographics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality -Linear Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adj R-squared | 0.655 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.658 | 0.658 | 0.642 | 0.144 | 0.789 | 0.663 |

| No. Clusters | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Notes: OLS estimates of eq. (1) are shown except for col. (7) which reports coefficients from a negative binomial model. The sample spans 1880 to 1920 and includes 60 municipalities (Swampscott and Nahant are combined). The dependent variable is the log of the child mortality rate (in Panel A), the number of child deaths in col. (7) of Panel B and the child mortality rate (in cols. 8 and 9 of Panel B). Safe water is an indicator variable equal to one during the year when municipal water or a water filter (in the case of Lawrence) was introduced. Sewerage is an indicator variable that equals one in the year a municipality was connected to the metropolitan sewerage district or had a sewerage system financed by the Commonwealth (in the case of Marlborough and Clinton). The interaction is an indicator variable that equals one in the first year both interventions are provided to a municipality. The combination of the estimated effects of water, sewerage and their interaction is in italics and the p-value associated with the combination is shown below it. Demographic controls include percentage of the population that is foreign-born, percentage male, percentage females in manufacturing and the log of population density.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

TABLE 3.

The Effect of Safe Water and Sewerage on Specific Categories of Death and Heterogeneous Effects

| Panel A: Category of Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Spring-Summer | Fall-Winter | Gastrointestinal | Respiratory | Tuberculosis |

Non-Child Mortality Rate |

|

|

|

||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

|

||||||

| Safe Water | 3.542 | 2.413 | 1.193 | 1.045 | 0.136 | −0.021 |

| (2.569) | (1.885) | (0.783) | (0.829) | (0.527) | (0.445) | |

| Sewerage | −1.965 | −1.475 | −1.709 | 0.407 | −0.195 | 0.346 |

| (1.964) | (0.983) | (1.241) | (0.529) | (0.308) | (0.299) | |

| Interaction of Safe Water and Sewerage | −8.249** | −6.053*** | −3.883*** | −3.208*** | −0.348 | 0.504 |

| (3.088) | (2.229) | (1.158) | (1.056) | (0.634) | (0.574) | |

| −6.672** | −5.114*** | −4.399*** | −1.756* | −0.407 | 0.828 | |

| Safe Water + Sewerage + Interaction | p-value=0.021 | p-value=0.005 | p-value=0.001 | p-value=0.052 | p-value=0.527 | p-value=0.144 |

| Observations | 2,440 | 2,440 | 2,440 | 2,440 | 2,440 | 2,440 |

| Adj R-squared | 0.651 | 0.449 | 0.631 | 0.324 | 0.233 | 0.616 |

| No. Clusters | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

|

| ||||||

| Panel B: Heterogeneous Effects | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| > 50th pctile Population Growth Rate (1880–1920) | ≤50th pctile Population Growth Rate (1880–1920) | > 50th pctile British (1880) | ≤50th pctile British (1880) | > 50th pctile Irish (1880) | ≤50th pctile Irish (1880) | |

|

|

||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

|

||||||

| Safe Water | 0.172 | 0.051 | 0.156 | 0.015 | 0.174** | 0.130 |

| (0.106) | (0.045) | (0.093) | (0.041) | (0.083) | (0.082) | |

| Sewerage | −0.028 | −0.059 | −0.029 | −0.083 | −0.027 | −0.094 |

| (0.067) | (0.062) | (0.057) | (0.059) | (0.055) | (0.056) | |

| Interaction of Safe Water and Sewerage | −0.348** | −0.175 | −0.285** | −0.323** | −0.502*** | −0.184* |

| (0.134) | (0.197) | (0.126) | (0.134) | (0.150) | (0.093) | |

| −0.203* | −0.183 | −0.158 | −0.391*** | −0.355** | −0.148 | |

| Safe Water + Sewerage + Interaction | p-value=0.065 | p-value=0.399 | p-value=0.187 | p-value=0.002 | p-value=0.010 | p-value=0.146 |

| Observations | 1,189 | 1,187 | 1,187 | 1,189 | 1,189 | 1,187 |

| Adj R-squared | 0.710 | 0.623 | 0.697 | 0.630 | 0.611 | 0.711 |

| No. Clusters | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

Notes: OLS estimates of eq. (1). The sample is unbalanced spanning the years 1880 to 1920 and includes the 60 sample municipalities when feasible. The dependent variables for Panel A are category- and age-specific mortality rates: col. (1) Spring-Summer = child mortality rate constructed from deaths during the months of April to September; col (2) Fall-Winter = child mortality constructed from deaths during the months October to March; col. (3) Gastrointestinal = child mortality from diseases that are associated with the gastrointestinal tract and/or are transmitted by fecal-oral route; col (4) Respiratory = child mortality from diseases that affect the lungs, exclusive of tuberculosis; col. (5) Tuberculosis = child mortality from tuberculosis in all forms; and col. (6) Non-child mortality rate (over-five mortality). For precise definitions and data sources see the Appendix. The dependent variable for Panel B is the log of the child mortality rate. The sample is described at the top of the column heading, with >50th percentile Irish, denoting municipalities in the top 50th percentile of the percent foreign who are Irish-born, in the baseline year of 1880. Other columns are defined similarly. Safe water is an indicator variable equal to one during the year in which municipal water or a water filter (in the case of Lawrence) was introduced. Sewerage is an indicator variable that equals one in the year a municipality was connected to the metropolitan sewerage district or had a sewerage system built for it by the Commonwealth (in the case of Marlborough and Clinton). The interaction is an indicator variable that equals one in the first year both interventions are provided to a municipality. The linear combination of water, sewerage and the interaction is provided in italics. Demographic controls included in every regression include percentage of the population that is foreign-born, percentage male, percentage females in manufacturing and log population density. Also included are municipality and year fixed effects and municipality-specific linear trends. Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Cols. (1) and (2) test whether the water or sewerage intervention had a significant impact on child mortality. These regressions provide estimates of the impact of one of the interventions neglecting the role of the other. The results suggest that the introduction of water (ignoring the role of sewerage) reduced child mortality by 12.6 log points and the introduction of sewerage (ignoring the role of water) reduced it by 12.3 log points. In col. (3) we include both safe water and sewerage. Each estimate has the expected sign, but only sewerage is significant. Sewerage and water (in col. 4) taken together are economically and statistically significant. These regressions do not include the separate main effects and thereby consider the full treatment as the combination of sewerage and safe water (as in a fixed proportions production function).

We next test whether the two interventions are complements or substitutes by adding the interaction of the two in col. (5). By including the main effects with the interaction term, the coefficient on water identifies the effect of having only water (similarly only sewerage), whereas the interaction tests if the two are complements or substitutes. The sum of the difference-in-differences coefficients reflects the full effect of implementing water and sewerage interventions.

Our evidence points to a strong complementarity between the two interventions and indicates their combined effect reduced child mortality by 26.6 log points (and that much of the reduction is driven by the interaction term).36 In Appendix Table B2, we repeat the analysis focusing exclusively on infant and under-two mortality. The results obtained are similar.37

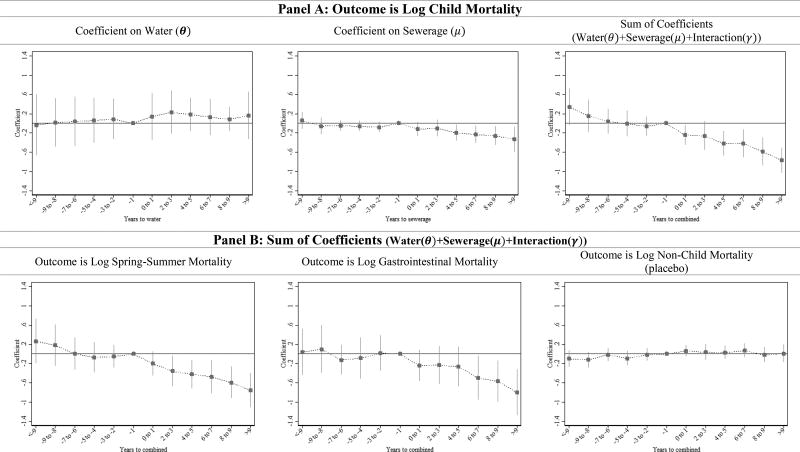

Figure 2 uses eq. (2) to map out the dynamic response to the introduction of the combination of the safe water and sewerage interventions. Panel A plots coefficients from a single regression. The outcome variable is the log of the child mortality rate. The graph on the left plots the event study coefficients on water, the middle graph plots sewerage coefficients, and that on the right plots the full effect of the interventions by adding together the coefficients on water, sewerage and the interaction. Panel B also plots the total combined effect of the interventions for three different outcomes: the graph on the left plots the event-study coefficients for (log) seasonal mortality (spring and summer), the middle plots the same for (log) gastrointestinal mortality and the graph on the right plots the coefficients for a placebo outcome, the (log) mortality rate for those five years and older.38

FIGURE 2.

Event Studies of the Efect of Sewerage, Water, and their Combination on Mortality by Age and Category of Death

Notes: OLS estimates of eq. (2) and their 95 percent confidence intervals are given. Panel A plots coefficients from one regression with the outcome log of child mortality, which includes the deaths of infants and young children [1, 5) years of age per 1,000 under-five population. Reading from left to right are the coefficients on water (θk), the coefficients on sewerage (μk), and the sum of coefficients: Water(θ)+Sewerage(μ)+Interaction(γ). Plotted in Panel B are the sum of coefficients: Water(θ)+Sewerage(μ)+Interaction(γ) using three different outcome variables (i.e., three different regressions): the log of the child mortality rate during the spring and summer, which is deaths during the months of April to September per 1,000 under-five population; the log of the child mortality rate from gastrointestinal disease; and the log of the non-child mortality, which is deaths of those five and above per 1,000 relevant population. See Data Appendix (variables definition), and text for further details. Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level.

All six of the event studies demonstrate that in the years preceding the intervention, conditions were neither systematically getting worse nor were they getting better. Comparing across the event studies in Panel A demonstrates that water alone did not have an appreciable effect on child mortality, sewerage had a small effect, and the combination produced a rapid decline. The set of figures also weakens the notion that a lagged effect of sewerage or water could be driving the main results. The results in Panel B indicate that the combination of interventions led to an immediate and persistent decrease in gastrointestinal and spring-summer mortality. The effects, moreover, increased with time probably due to the spread of sewerage connections within the treated municipalities. The connection to safe water was more immediate.

Each of the municipalities was required to own their water pipes before the water intervention.39 When the new source was available, water could immediately flow into residences. In fact, after the water was available the Metropolitan Water Board was alarmed by what they saw as rampant wastage, and their concern prompted the installation of water meters. Regarding sewerage, however, after the main trunk lines were connected to the outfalls in the Harbor, branching lines within the municipality and some separate residences had to be connected. Although there was an immediate jump in the miles of local sewerage connected to the District (Appendix Figure B8), connections continued to increase as more neighborhoods were “drained.” The need for connections within municipalities could account for the increased beneficial effect of the sewerage and combined treatment with time.

Thus, the time pattern of change we show in Figure 2 accords well with the historical information about the safe water and sewerage projects and with the time course of disease. Since diarrhea is an acute disease, interventions that protect children from transmission should translate into a swift decline in mortality.

In Table 2 Panel B we report results obtained using variations in our baseline specification. These alternative specifications vary by column heading. We assess the robustness of our results to county-year fixed effects (col. 6), the use of a count model (col. 7) and a linear-in-levels model specification both weighted (col. 8) and unweighted (col. 9). The results presented in Panel B are generally consistent with those reported in Panel A, and demonstrate the failure of a piecemeal approach to infrastructure improvements. Weighting by the under-five population attenuates our results; though as we show in Table 3 this is likely due to smaller municipalities with higher population growth rates benefitting more from the combination of interventions.40

2. Channels

How were young children affected by potentially contaminated water and why did they benefit so greatly from both safe water and sewerage interventions? Most babies were not exclusively breastfed throughout but were, instead, often fed a gruel that contained water as were toddlers. Detailed information on breastfeeding practices from the extensive Children’s Bureau Bulletins of the late 1910s and early 1920s shows that around half of all surviving infants were exclusively breastfed at six months, about a quarter were wholly bottle fed at six months and the rest were nurtured by a combination of the two methods (U.S. Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau 1923).41 Women in low-income families who worked outside the home were less likely to breastfeed, although differences in breastfeeding practices by family income were not large. Furthermore, some women were not able to breastfeed independent of family income.

Even for women who did breastfeed, it was a common practice, later condoned and recommended by the Children’s Bureau, to feed infants water. The advice often came with the admonition to boil water, but that was not always the case. “When the baby cries between feedings [at the breast] give him pure, warmed water without anything in it. Then let him alone” (U.S. Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau 1914, p. 50).42 Even if babies were not deliberately given water, they were bathed in water that may have been polluted. Finally, flies landing on feces could have spread disease to milk or gruel that was fed to young children.

Evidence presented in Table 3 on deaths by season and disease category bolsters the claim that the water and sewerage interventions greatly reduced gastrointestinal disease and improved the survival of children. The table begins with seasonal mortality since the prevalence of gastrointestinal disease increases in warmer months due to spoilage and flies, and the mortality rate conditional on infection rises as children more easily succumb to dehydration.43 We find that the full effect of water and sewerage reduced deaths during the warmer months by 6.7 per 1,000 under-five population as compared to fall-winter mortality by 5.1 per 1,000 under-five population. In cols. (3) and (4) we find that the full effect was greater for gastrointestinal mortality (4.4 per 1,000) than for respiratory mortality exclusive of tuberculosis (1.8 per 1,000).

In cols. (5) and (6) we find no significant effect of the interventions on tuberculosis or on the non-child mortality rate. Tuberculosis is generally transmitted through airborne droplets and should be less affected by water and sewerage interventions, though contaminated dairy products might have played a role in transmission during this period. Given that the overwhelming cause of death for adults at the time was pulmonary tuberculosis, we view these findings as supportive of the notion that the channel by which safe water and sewerage interventions improved child survival was by greatly reducing deaths from diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

3. Heterogeneous Effects

We investigate whether the impact of the infrastructure improvements depended on the percentage of foreign-born by municipality. We divide municipalities by the median percentage of various demographic groups in 1880 (the last U.S. census before the interventions). Using the period prior to interventions obviates concerns about endogenous migration response to the interventions (though Table 4 fails to demonstrate any significant migration response).

TABLE 4.

The Effect of Safe Water and Sanitation on the Composition and Demographic Features of the Municipality

|

Percentage Foreign |

Percentage Male |

Percentage Females in Mfg |

Percentage Females Illiterate |

Percentage British |

Percentage Irish |

Log Total Population |

Log Total Births |

Log Foreign Births |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| Safe Water | −0.020 | −0.158 | −0.256 | 0.104 | 0.390 | −0.055 | 0.030 | 0.021 | 0.040 |

| (0.752) | (0.753) | (0.682) | (0.432) | (0.298) | (0.399) | (0.037) | (0.039) | (0.064) | |

| Sewerage | 0.749 | −0.450 | 0.541 | −0.248 | −0.011 | 0.753** | 0.070 | 0.048* | 0.070 |

| (1.024) | (0.577) | (0.340) | (0.269) | (0.147) | (0.319) | (0.043) | (0.027) | (0.055) | |

| Interaction of Safe Water and Sewerage | −0.667 | −0.570 | 0.202 | 0.200 | −0.188 | −0.377 | −0.051 | −0.027 | −0.041 |

| (1.013) | (0.835) | (0.646) | (0.524) | (0.312) | (0.436) | (0.040) | (0.053) | (0.079) | |

| Safe Water + Sewerage + Interaction | 0.062 | −1.178 | 0.487 | 0.055 | 0.192 | 0.321 | 0.050 | 0.043 | 0.068 |

| p-value=0.970 | p-value=0.131 | p-value=0.286 | p-value=0.882 | p-value=0.337 | p-value=0.267 | p-value=0.333 | p-value=0.333 | p-value=0.383 | |

| Observations | 535 | 535 | 535 | 535 | 535 | 535 | 535 | 2,440 | 2,440 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Demographics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality -Linear Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adj R-squared | 0.878 | 0.643 | 0.975 | 0.928 | 0.967 | 0.982 | 0.992 | 0.990 | 0.982 |

| No. Clusters | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Notes: OLS estimates of eq. (1). The sample is unbalanced spanning 1880 to 1920 and includes the 60 sample municipalities. Each column is a separate regression with a different outcome variable. The outcome variables listed under the column numbers are derived from the MA and U.S. Censuses as described in Appendix A. Safe water is an indicator variable equal to one during the year in which municipal water or a water filter (in the case of Lawrence) was introduced. Sewerage is an indicator variable that equals one in the year a municipality was connected to the metropolitan sewerage district or had a sewerage system built for it by the Commonwealth (in the case of Marlborough and Clinton). The interaction represents an indicator variable that equals one in the first year both interventions are provided to a municipality simultaneously. The linear combination of water, sewerage and the interaction is in italics. Demographic control variables (percentage foreign-born, percentage male, percentage females in manufacturing, log population density) exclude the outcome variable when applicable. Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Our findings, presented in Table 3 Panel B demonstrate that the full effects of water and sewerage had a significant effect on the mortality of children in certain municipalities. As alluded to above in the discussion of weighting, we find effects of the interventions are largest and only statistically significant for municipalities that experienced the most rapid population growth during the analysis period (cols. 1 and 2). Municipalities with more foreign-born residents, especially those who lived in crowded and squalid conditions, would have had the most to gain from sewage removal and clean water interventions. But political economy considerations could have led the foreign-born enclaves to be excluded from the expansion of sewerage connections. But when we decompose the foreign population by major ethnic groups, we find that sewerage and water combined led to a 35.5 log point decline in child mortality for municipalities with more Irish-born inhabitants. These effects are much larger than are those for places with more foreign-born of British descent (full effect of 15.8 log points) and larger than places with fewer Irish, suggesting that a socially and economically marginalized group in the Boston area gained disproportionately from the public health investments.

We have presented evidence bolstering the notion that clean water and sewerage interventions together greatly reduced child mortality. But could the interventions have not directly improved health but, instead, changed the composition of the population? Higher income persons and the health conscious could have migrated to less odiferous and clean water places.

To examine the possibility of a composition effect we modify eq. (1) and replace mortality rates with the percentage of the population that meets some demographic criteria. The analysis, given in Table 4 cols. (1) through (6), is estimated on a limited sample due to the availability of the dependent variable only in the quinquennial state and decennial federal censuses. Nevertheless, the results point in the direction that compositional changes are not a major explanation for our findings. An unusual exception is the positive correlation between the variation in the sewerage intervention and the percentage Irish.

Another possibility is that changes in child mortality led to a decline in fertility or to migration. But we find no migration response to the interventions (col. 7). At the annual level, there does not appear to have been an immediate fertility response to the combination of the interventions in the general population (Table 4, col. 8), consistent with a fairly stable fertility rate for the period (Haines 1998b).44 There is, moreover, no statistically significant correlation between foreign births and the rollout of the interventions (col. 9).

4. Robustness

We assess the robustness of our results in Table 5 and Appendix Table B3 to adding further time-varying municipality-level controls, using different samples, changing the mode of statistical inference, and removing or adding various trends. We begin, in Table 5 col. (1), by adding a proxy for milk supply quality at the county level. Milk quality is measured imprecisely and does not reach statistical significance. In col. (2) we control for the percentage of females who were illiterate since maternal education is known to be a strong predictor of child survival. But inclusion of the variable does not change the relevant point estimates.45

TABLE 5.

The Effect of Safe Water and Sewerage on Log Child Mortality

| Dairy Quality | Female Literacy | Externalities | Treated Only | Drop 3 Municipalities |

Move 3 Municipalities to Controls |

Move Springfield to Treated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Safe Water | 0.109 | 0.110 | 0.086 | 0.106 | 0.123 | 0.129 | 0.124* |

| (0.080) | (0.085) | (0.086) | (0.103) | (0.102) | (0.101) | (0.067) | |

| Sewerage | −0.066 | −0.075 | −0.100 | −0.080 | −0.048 | −0.045 | −0.068 |

| (0.045) | (0.046) | (0.061) | (0.069) | (0.049) | (0.048) | (0.045) | |

| Interaction of Safe Water and Sewerage | −0.307*** | −0.303*** | −0.328** | −0.297** | −0.334*** | −0.334*** | −0.322*** |

| (0.106) | (0.112) | (0.129) | (0.114) | (0.121) | (0.121) | (0.102) | |

| Safe Water + Sewerage + Interaction | −0.264*** | −0.267*** | −0.343*** | −0.271* | −0.259*** | −0.250*** | −0.265*** |

| p-value=0.006 | p-value=0.006 | p-value=0.003 | p-value=0.070 | p-value=0.009 | p-value=0.010 | p-value=0.006 | |

| F-test of Joint Significance | p-value=0.367 | ||||||

| Observations | 2,438 | 2,438 | 2,438 | 1,269 | 2,315 | 2,438 | 2,438 |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Demographics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Municipality -Linear Trends | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| No. Clusters | 60 | 60 | 60 | 31 | 57 | 60 | 60 |

Notes: OLS estimates of eq. (1). Each column is a separate regression. The sample specification varies across columns. Col. (1) adds the percent of dairy milk at the county level that is high quality (see Appendix A); col. (2) adds the percentage of females illiterate; col. (3) adds controls for the percent of neighbors with sewerage or water or both; col. (4) limits the sample to only those municipalities that eventually received an intervention; col. (5) drops three municipalities: Lawrence (which had a filter) and Clinton and Marlborough (which had sewerage systems financed by the Commonwealth); col. (6) treats Clinton, Marlborough and Lawrence as controls; col. (7) adds Springfield as a water intervention municipality. Safe water is an indicator variable equal to one during the year in which municipal water or a water filter (in the case of Lawrence) was introduced. Sewerage is an indicator variable that equals one in the year a municipality was connected to the metropolitan sewerage district or had a sewerage system financed by the Commonwealth (in the case of Marlborough and Clinton). The interaction is an indicator variable that equals one in the first year both interventions were provided to a municipality. The linear combination of water, sewerage and the interaction is provided in italics. Year and municipality fixed effects are included in every specification as are demographic variables (percentage of the city population that is foreign-born, percentage male, percentage females in manufacturing and log population density). Municipality-linear trends included except when replaced with alternative trends or dropped from the analysis as indicated in column heading. Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

We also assess whether our results are driven by externalities among municipalities by including the share of neighboring municipalities with either sewerage or water interventions (those with both contribute to each separately). We find that controlling for spillover effects has no meaningful impact on the main results concerning the impact of pure water and sewerage for a given municipality.46

We next check the robustness of our results to varying the sample in ways that are meaningful to how it was selected. In col. (4) we use only municipalities that eventually received at least one intervention, thus exploiting variation in time to the intervention only. The estimate of the combined effect is almost identical to that for the full sample, though with a somewhat larger standard error. In col. (5) we exclude three municipalities: Lawrence (which had a filter), and Marlborough and Clinton (whose sewerage systems were financed by the state). In col. (6) we move the three municipalities to the control category. In both cases, the estimates of the combined effect are relatively unchanged (25.9 and 25.0 log point decline in mortality) and remain significant. In the last column of Table 5, we consider Springfield as a treatment municipality because it improved its water supply during our analysis period. Changing the sample in these ways has little effect on our results.

In Appendix Table B3, we use standard errors that correct for: (col. 1) spatial correlation, and (col. 2) a small number of clusters. The combined effect of water and sewerage remains highly significant. In the last set of robustness checks, we vary the included trends. In col. (3) we add quadratic trends, in col. (4) intervention-specific linear trends, in (col. 5) we add breaks in trends by intervention date, in col. (6) we include trends by baseline demographic features of the municipality as well as distance from the State House, and in (col. 7) we exclude all trends. These robustness checks provide further support for the notion that municipalities were not chosen based on patterns of survival of their youngest residents and are not particularly sensitive to various samples or specifications.

IV. Concluding Remarks

We find robust evidence that the pure water and sewerage treatments pioneered by far-sighted public servants and engineers in the Commonwealth saved the lives of many infants and young children. These interventions must also have improved the health of and enhanced the quality of life for the citizens of the Greater Boston area even if they did not greatly reduce the non-child death rate.47

Using our preferred specification, the combination of sewerage and safe water together lowered the child mortality rate by 26.6 log points or 33.6 percent of the total change in treatment municipalities. The combination also lowered the infant mortality rate by 22.8 log points or 48 percent of the total change in treatment municipalities, which is close to the 47 percent estimate from Cutler and Miller (2005) in their study of filtration and chlorination for a somewhat later period across 13 U.S. cities.

Can we say that the benefits from the treatments were worth the cost? The question is a difficult one since there were many benefits and we focus on just one. If the only benefit was the reduction in child mortality, what was the cost of an averted death? We answer the question using data for 1910, about in the middle of the treatment period we consider. We produce hypothetical child deaths as of 1910 in the 15 municipalities (excluding Boston) that received both water and sewerage treatments.

In 1910, there were 36,801 children less than five years in these municipalities, and the deaths of 440 were averted in that year by the treatments. What about the cost? Since the benefit (averted deaths) is on an annual basis, the cost must be. We consider the cost only for the sewerage system since it was imposed on the municipalities. The total sewerage assessment for the 15 municipalities in 1910, which was to cover the interest and sinking fund on the project plus maintenance, was around $300K.48 Therefore, each death prevented per year came at a cost of $682, about equal to the annual earnings of a manufacturing worker.

But there were a great many other benefits from the projects. Illness must have declined for all and the quality of life was improved. In fact, the “stench” was what first sparked public activism to rid Boston of the sewage. The water project was also an expense, but it alone had little impact on child mortality and the creation of the watershed area was completely dependent on the removal of effluent. All towns had a water supply before the watershed project but in many cases the water was of questionable purity because of sewage.

The answer we have offered for the first decline in child mortality differs from that of many contemporary observers in the early twentieth century, and some who have contributed to the literature on the historical decline for the U.S. and Europe.49 Yet a spate of research in economics has focused on clean water technologies and their influence on public health, particularly typhoid mortality.

The lessons from our historical study are clear. Without proper disposal of fecal material, the benefits of clean water technologies for the health of children are limited. Although the management of diarrheal illness has improved greatly since the early twentieth century, clean water and sanitation still pose daunting global challenges. According to UNICEF (2014) more than 700 million people lack ready access to improved sources of drinking water and some 2.5 billion people do not have an improved sanitation facility. Each day, an estimated 3,000 children under five years of age die because of diarrheal disease and millions of school days are lost. Further, chronic exposure to fecal pathogens may lead to inflammatory changes in the gut that preclude the absorption of essential nutrients and that stunt height, retard cognitive development and increase susceptibility to other diseases (Korpe and Petri 2012; Yu et al. 2016).50

Although health challenges in late nineteenth century U.S. cities were similar to those in modern day developing nation cities, there are important differences. The clean water technology we investigate was primitive. It consisted of protecting watersheds rather than employing a later technology of chlorination, which has a more persistent germ killing effect. Still, the impact of chlorination on health might be muted if systems for sewage disposal are not also in place.51 Our findings accord with recent results from community-level water and sanitation infrastructure improvements in India. Together, the interventions were found to reduce diarrheal episodes by 30 to 50 percent (Duflo et al. 2015).

Finally, one may wonder why the Commonwealth government was so foresighted and why municipalities agreed to raise taxes to prevent downstream pollution and protect the watersheds. Although a full account of political economy considerations is beyond the scope of our work, extensive writing on this important issue reveals the respect that politicians and the people gave to the water engineers and health officials who, in their writings, showed an understanding of the roles of unsafe water and sewage in spreading disease, even as miasmatic theories still abounded in the population. We quote Whipple (1917, p. 134) on these matters: “so great has been the confidence of the public in the ruling of the [State] Board [of Health] that its letters have come to have almost the force of law.”

We have identified that the combination of safe water and sewerage interventions was responsible for much of the first sustained decrease in child mortality in the U.S. Yet child mortality continued its long decline. Later in the Progressive Era, the purification of the milk supply, street cleaning, health stations, vaccinations and nurse home visits reduced mortality.52 Still later in the twentieth century, a host of medical technologies, including antibiotics, continued to lower infant and child death rates. Closer to the present, the use of neonatal intensive care units has spared many premature babies. Yet improving the lives of young children in much of the developing world still involves decreasing morbidity from diarrheal disease through a combination of safe water and sewerage system interventions just as it did during the first decline in the U.S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Anjali Adukia, Ben Arnold, Jay Bhattacharya, Hoyt Bleakley, Prashant Bhardwaj, Pascaline Dupas, Steve Cicala, David Cutler, Daniel Fetter, Will Dow, Joseph Ferrie, Paul Gertler, Michael Haines, Rick Hornbeck, Larry Katz, Steve Luby, David Meltzer, Grant Miller, Nathan Nunn and participants at the DAE NBER Summer Institute, University of Chicago Harris School Seminar, the All-UC Conference “Unequal Chances and Unequal Outcomes in Economic History,” Harvard Economic History Workshop, the Mini-Conference on Inequality and Mortality at University of California, Berkeley and the Population Association of America Conference. For outstanding research assistance, we thank Natalia Emanuel, Megan Prasad, Ali Rohde, Alex Solis, Anlu Xing, Morgan Foy and Mario Javier Carrillo. We also thank the editor of this journal and the referees, who offered informed and beneficial suggestions.

Footnotes

Child mortality means deaths to those less than five years of age and includes infant mortality. The “infant mortality rate” is the number of infants less than one year of age who died during a year divided by the number of births in that year. The historical literature on U.S. infant mortality includes Cheney (1984), Condran and Lentzner (2004), Condran and Murphy (2008) and Preston and Haines (1991). Seminal contributions include Cain and Rotella (2001), on water and sewerage infrastructure by major city; Condran and Cheney (1982), on mortality changes within Philadelphia; Condran and Crimmins-Gardner (1978), demonstrating the importance of public works in the decrease of waterborne diseases; Ferrie and Troesken (2008), on clean water and a general decline of non-waterborne diseases; and Meeker (1972), a pioneering piece on waterborne disease and river spillovers. See also Beach, Ferrie, Saavedra and Troesken (2016), on long-run payoffs to water purification; Galiani, Gertler and Schargrodsky (2005), on privatization of water services in Argentina; and Troesken (2001, 2002) on race-specific typhoid mortality and water provision. How cities began to clean up their acts in the early twentieth century is told in part by Cutler and Miller (2006), which emphasizes the growth of financial markets.

Cutler and Miller (2005, table 5) compute the decrease in IMR due to clean water and sanitation to be 46 log points from 1900 to 1936 in their 13 cities. The total decrease was 98 log points (log [189.3/71.3], table 2) or 47 percent. Their paper reports a 74 percent change, but they have posted a correction.

Cutler and Miller (2005) analyze two discrete water interventions, not sewerage. Research contributions on sanitation interventions and mortality include, but are not limited to, Brown and Guinnane (2015) on Bavaria, Kesztenbaum and Rosenthal (2014) on early twentieth century Paris, Preston and Van de Walle (1978) on nineteenth century France, and Watson (2006) on U.S. Indian reservations.

The aptly named “F-diagram” of fecal-oral disease transmission and control (Wagner and Lanoix 1958) demonstrates how feces can lead to disease transmission through the “5 F’s” fingers, fluids (water supply), flies, fields/floor and food (occasionally flooding is included). Even with clean water, feces can re-contaminate water.

See Whipple (1917).

We provide evidence in Section II B and Appendix Table B1 that intervention completion dates were determined largely by technical engineering factors, not political issues or health concerns.

See Haines (1979, 1998a) on the aggregate series, which is largely inferred from model life tables and also uses the 1900 and 1910 U.S. population censuses on ever born and surviving children. See Shattuck (1850) on the establishment of the Commonwealth’s vital statistics collection.

The United Nations data (2005–10) on infant mortality lists eight nations with a rate exceeding 100/1,000 (all under 127 and in Africa). See http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Excel-Data/mortality.htm

Preston and Haines (1991) confirms the urban penalty. See also Glaeser (2014).

In Appendix Figure B2 to B5 we demonstrate the distribution of deaths by age and by broad categories for children under five and the seasonality of deaths from all causes.

The unweighted sample is used and a five-year average of log CMR is used at the start and at the end because of volatility.

Infant mortality also declined in Europe in the early twentieth century. In England and Wales the rate remained in the 150/1,000 range until around 1900 when it decreased to 130 and then to 100 by 1910. See Woods, Watterson and Woodward (1988, 1989) who discuss the roles of clean water and proper sanitation but not as the major causes.

In 1898 the Metropolitan Sewerage District, with Boston, had 36 percent of the state’s population and 55 percent of its total assessed valuation, but just 2.5 percent of its land area. The “District” included 23 towns: Arlington, Belmont, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Dedham, Everett, Hyde Park (became part of Boston), Lexington, Malden, Medford, Melrose, Milton, Newton, Quincy, Somerville, Stoneham, Wakefield, Waltham, Watertown, Winchester, Winthrop, and Woburn (Metropolitan Sewerage Commission of Boston 1899, p. 3).

In addition to the immediate Harbor watershed area of the Charles, Mystic and Neponset River Valleys, the Commonwealth paid for sewerage infrastructure in the towns of Clinton and Marlborough. Both are included in our main analytical sample but are dropped, and moved to control municipalities in robustness checks (see Table 5 and Appendix Table B3).

The General Court of Massachusetts resolved that the engineers appointed to the Sewerage Commission were to “designate the cities and towns…which shall be tributary to and embraced by the district” and “determine and show, by suitable plans and maps, such trunk lines and main branches as it shall recommend to be constructed, with outlet” (Massachusetts State Board of Health 1889, p. 3–4).

Timing to sewerage and water are modeled separately since distinct engineering factors affected each. Time to the interaction is difficult to model since many geographic considerations may have differentially impacted the infrastructure timing. The Charles River System, begun in May 1890, was completed in spring 1892 despite “difficulties.” It was the fastest to complete since it was an extension of the extant Boston system. The North Metropolitan System began the same time as the Charles River System but “was slower in progress and much later in its completion” since it required a new pumping station and other engineering challenges. The Neponset Valley System was mainly completed in 1897. The High-level System was still in progress in 1899 (Metropolitan Sewerage Commission of Boston 1899, p. 15).