Abstract

Metalloamination-alkylation of representative N,N-dimethyl-hydrazinoalkenes has been shown to be effectively catalyzed by CuBr-SMe2, CuCN, and Cul. The current method obviates the use of stoichiometric CuCN(LiCl)2 as a promoter for the electrophilic functionalization event.

Keywords: metalloamination–cyclization, Cu(I) catalysis, allylation

Graphical Abstract

Saturated N-heterocycles have come to be recognized as privileged scaffolds for drug discovery and development as a consequence of their decreased lipophilicities, improved solubility, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics.1a,b This class of heterocycles, many of which contain chiral centers, presents synthetic challenges that are often not well addressed by traditional synthetic methods.1c We have previously advanced a powerful new method for achieving N- C/C-C bond construction by way of simultaneous N-C/C-Zn metalloamination.2a,b Several laboratories have documented synthetically viable methods for achieving sequential N-C → C-M → C-C bond formation, with the seminal discoveries of the Bower,3a,b Chemler,3c,d Knowles3e-g and Wolfe3h-k laboratories being major advancements.4 From a synthetic standpoint, it is significant that virtually all current procedures are limited in the final C-C bond-forming step due to the fleeting nature of their requisite organometallic or free-radical intermediates. By way of contrast, our work involves the intermediacy of organozinc reagents, which are comparatively robust and can be synthetically differentiated via numerous C-Zn functionalization procedures. In addition, many of the catalytic metalloamination methods for forming five-membered rings (as well as the very few that give six-membered rings) greatly benefit from conformational biasing effects favoring annulation. In contrast, our Zn(II)- mediated annulation procedure is not reliant on conformational constraints. We have previously reported that stoichiometric CuCN(LiCl)25 is an effective reagent for promoting allylations of the C-Zn bond present in nitrogenous heterocycles of the type 2.2a,b In this communication we show that CuBr-SMe2, CuCN, and CuI are effective catalysts for allylation at carbon.

The influence of aromatic solvents on the efficiency of metalloamination was initially investigated by a direct comparison of toluene to its more polar counterpart benzotrifluoride (BTF).6 Whereas the use of each of these solvents resulted in excellent conversion (>95%) of the N,N-dimethylhydrazinoalkene 1a to the corresponding cyclic organozinc 2a at 90 °C, reactions conducted in BTF proceeded more rapidly, requiring six hours compared to 24 hours when PhMe was employed. From the standpoint of economics, the use of chlorobenzene led to metalloamination in the intermediate range of 12 hours. In addition, the ‘π- excessive’ aromatic thiophene was found to offer no obvious advantages as a solvent over chlorobenzene or PhMe (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Metalloamination-allylation of N,N-dimethyl-hydrazinoalkenes

The efficacy of selected Cu(I) salts (and complexes) as allylation catalysts was then studied. From the standpoint of experimental simplicity, it is noteworthy that the ‘conventional’ Cu(I) sources CuBr-SMe2, CuCN, and CuI proved to be excellent catalysts for the conversion of 2a to 3a.

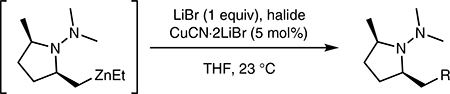

In a representative experimental procedure, exposure of 1a (0.10 mmol) to Et2Zn (1.0 equiv as a 2.0 M solution in BTF) in BTF (0.4 mL) at 90 °C for six hours generated 2a (≥95%, as a 20:1 cis/trans diastereomeric mixture).7 Subsequently, tetrahydrothiophene (THT, 0.1 mL), CuBr-SMe2 (1.02 mg, 5 mol%), and allyl bromide (4 equiv) were added in succession. Allylation was monitored by 1H NMR at 23 °C for 12 hours, whereupon complete conversion into 3a was achieved. Upon workup (vide infra) the pyrrolidine 3a (95%, dr ≥ 20:1) was furnished as a clear liquid (which could also be conveniently isolated as the trifluoroacetate salt). Although methallyl chloride had previously been found highly satisfactory as a trapping agent when stoichiometric CuCN(LiCl)22a was used as a promoter, this complex proved much less effective when used as a catalyst (5 mol%) with the less reactive methallyl chloride. In sharp contrast, the use of CuCN(LiBr)2 admixed with LiBr (1 equiv) led to rapid and highly efficient methallylation (possibly due to an internal Finkelstein activation process). Additionally, the use of THT as a Cu(I) stabilizer was determined unnecessary. The simple addition of LiBr (1 equiv) also provided solutions of mixed Cu/Zn intermediates that were endowed with substantial lifetimes. Alternative Cu(I) complexes [i.e., CuBr-P(n-Bu)3, CuBr-P(2-furyl)3, CuCl-(PPh3)2] and CuSPh were subsequently tested and found to be inferior as catalysts, as was AuCl-PPh3. The results of this study are summarized in Table 1. In addition, Mo(CO)6 and Mo(CO)4 bipy8 were not competent as catalysts for the present transformation.

Table 1.

Catalyst Evaluation Using Allyl Bromide as the Electrophile

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst | tfinal | Yielda |

| 1 | CuBr.DMSc | 12 h | ≥95% |

| 2 | CuBr.DMSb,d | 3 h | ≥95% |

| 3 | CuCN.2LiBrb,d | 8 h | ≥95% |

| 4 | CuIc | 15 h | ≥95% |

| 5 | CuBr.P(2-furyl)3c | 12 h | 74% |

| 6 | CuBr.P(n-Bu)3c | 12 h | 70% |

| 7 | CuCl.2PPh3c | 22 h | 67% |

| 8 | PhSCub,c | 10 h | 65% |

| 9 | AuCl.PPh3c | 22 h | 25% |

Monitored by No-D 1H NMR7 using disappearance of C-Zn methylene peak to determine completion.

BTF was removed and allylation was performed in THF.

Reaction conducted with 1.1 equiv of THT.

One equiv of LiBr was added.

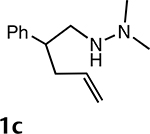

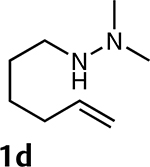

The synthetic scope of metalloamination-allylation was explored by subjecting additional N,N-dimethylhydrazino- alkenes (e.g., 1a-d) to an experimental protocol closely related to that described for the conversion of 1a into 3a. The details of this study are summarized in Table 2. The results presented in Table 2 are noteworthy in that the isolated yields are excellent in almost all cases. Significantly, the presence of Thorpe-Ingold conformational acceleration that is of crucial importance in many hydroamination- cyclizations is not a prerequisite for successful metalloami- nation-cyclization. In addition, these reactions were readily scalable (e.g., ≥1 mmol). Two examples are presented in entries 1 and 4, in which simple 5- and 6-membered rings are formed efficiently and with faster rates than observed for 1b (entry 2). In addition, excellent levels of diastereoselec- tivity are achievable. Specific cases include the metalloamination-allylation of 1a to provide pyrrolidines 3a (cis/trans ≥20:1) and 1c to give pyrrolidine 3c (cis/trans = 1:15).2a As revealed by Table 2, entry 4, facile metalloamination-allyla- tion is also extendible to the formation of piperidines from a Ν,Ν-dimethylhydrazinoalkene that lacks conformational biasing favoring ring closure (1d → 3d).

Table 2.

Metalloamination-Allylation of N,N-Dimethylhydrazinoalkenes Utilizing Allyl Bromide as the Electrophile

| Entry | Hydrazine | tcylclizea | tallylatione,f | drd | Productb | Yielda,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

6 h (90 °C) | 12 h (23 °C) | 20:1 |  |

≥95% |

| 2 |  |

18 h (90 °C) | 24 h (23 °C) | - |  |

≥95% |

| 3 |  |

24 h (23 °C) | 22 h (23 °C) | 15:1 |  |

90% |

| 4 |  |

1 h(60 °C) | 8 h (23 °C) | - |  |

≥95% |

| 5 |  |

24 h (23 °C) | 12 h (23 °C) | 6:1 |  |

80% |

| 6 |  |

– | – | – | – 3f |

– |

Monitored by No-D 1H NMR using BTF as the internal standard.7

Products were isolated as TFA salts.

A small quantity of the TFA salt of the starting N,N-dimethylhydrazinoalkene (1) was admixed with the product.

Diastereomeric ratios were derived from proton NMR.3e

Monitored by the disappearance of C-Zn methylene peak to determine completion.7

The allylation was catalyzed by CuCN(LiBr)2 and conducted in THF.

It is also significant that alternative halides readily participate in the C-functionalization process. Thus, the use of propargyl bromide provided allene 3aallene and methyl 2- (bromomethyl)acrylate furnished enoate 3amethacrylate in respectable yields (Table 3, entries 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Catalytic CuCN.2LiBr (5 mol%) Mediated Allylation of 1-Methyl- N,N-Dimethyl-4-pentene in THF with Representative Halides

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Halides | Time | Temp | Productb | Yielda,c |

| 1 | 12 h | 23 °C |  |

≥ 95% | |

| 2 |  |

10h | 23 °C |  |

≥ 95% |

| 3 |  |

5 h | 23 °C |  |

60% |

| 4 |  |

4 h | 23 °C |  |

65% |

Monitored by No-D 1H NMR using disappearance of C-Zn methylene peak to determine completion.7

Products were isolated as TFA salts subsequent to allylation in THF.

A small quantity of the TFA salt of the starting N,N-dimethylhydrazinoalkene 1 was admixed with the product.

In conclusion, we have shown that the readily available Cu(I) derivatives CuBr-SMe2, CuCN, and Cul are highly effective catalysts for the allylation of zinc-bearing azacycles generated by Et2Zn-driven metalloamination-cyclization of representative Ν,Ν-dimethylhydrazinoalkenes.9 Metalloamination-cyclization proceeded more rapidly in benzotrifluoride (BTF) and chlorobenzene than toluene, but all three solvents proved very well suited for overall cyclization-allylation. In addition, alternative attractive modes of electrophilic functionalization of the intermediate C-Zn bond have been revealed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

Generous financial support from the NIGMS (GM116949) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

This manuscript is dedicated to Professor Albert Padwa on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

Supporting Information

Supporting information for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1588578.

References and Notes

- (1) (a).Meanwell NA Chem. Res. Toxicol 2011, 24, 1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Welsch ME; Snyder SA; Stockwell BR Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Roughley SD; Jordan AM J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).Sunsdahl B; Smith AR; Livinghouse T Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 14352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sunsdahl B; Mickelsen K; Zabawa S; Anderson BK; Livinghouse TJ Org. Chem 2016, 81, 10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3) (a).Race NJ; Faulkner A; Fumagalli G; Yamauchi T; Scott JS; Ryden-Landergren M; Sparkes HA; Bower JF Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Faulkner A; Scott JS; Bower JF J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Turnpenny BW; Chemler SR Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liwosz TW; Chemler SR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Musacchio AJ; Nguyen LQ; Beard GH; Knowles RR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Choi GJ; Zhu Q; Miller DC; Gu CJ; Knowles RR Nature 2016, 539, 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Choi GJ; Knowles RR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Garlets ZJ; Parenti KR; Wolfe JP Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) White DR; Wolfe JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 11246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Babij NR; Wolfe JP Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Mai DN; Wolfe JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).For additional references, see:Piou T; Rovis T Nature 2015, 527, 86.Rong Zhu R; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 8069.Nicolai S; Sedigh-Zadeh R; Waser JJ Org. Chem 2013, 78, 3783.Nicolai S; Piemontesi C; Waser J Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 4680.Nicolai S; Waser J Org. Lett 2011, 13, 6324.Hoover JM; DiPasquale A; Mayer JM; Michael FM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 5043.Hoover JM; Freudenthal J; Michael FE; Mayer JM Organometallics 2008, 27, 2238.Hewitt JFM; Williams L; Aggarwal P; Smith CD; France DJ Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 3538.Cernak TA; Lambert TH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3124.Jana R; Pathak TP; Jensen KH; Sigman MS Org Lett. 2012, 14, 4074.Zhang G; Cui L; Wang Y; Zhang LJ Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 1474.Roveda J; Clavette C; Hunt AD; Gorelsky SI; Whipp CJ; Beauchemin AM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 8740.

- (5).Knochel P; Yeh MCP; Berk SC; Talbert JJ Org. Chem 1988, 53, 2390. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ogawa A; Curran DP J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hoye TR; Eklov BM; Ryba TD; Voloshin M; Yao L Org. Lett 2004, 6, 953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Trost BM; Lautens MJ Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 5543. [Google Scholar]

- (9).General Procedure for CuBr-SMe2-Catalyzed Metalloamination-AllylationAn oven-dried J. Young tube under an argon atmosphere was charged with Et2Zn (50 μL, 2.0 M in BTF, 0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), BTF (0.4 mL), and the requisite N,N-dimethylhydrazinoalkene (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The tube was then placed into an oil bath (of indicated temperature) and metalloamination-cyclization was monitored using BTF as an internal standard (as evidenced by the disappearance of the alkene signals with concurrent emergence of new C-Zn methylene peaks). The temperature of the reactant mixture was subsequently returned to 23 °C for the addition of THT (0.1 mL) followed by the addition of the Cu(I) catalyst (5 mol%). Allyl bromide (4.0 equiv) was then added and its consumption, with simultaneous recession of the intermediate C-Zn methylene resonance, was monitored by No-D proton NMR. Upon completion of allylation, the reactant mixture was dispersed in Et2O (2 mL) and washed with 1:1 sat. NH4Cl (aq)/sat. aq NH4OH (3 × 3mL). The aqueous layers were then extracted with Et2O (3 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried successively with brine (5 mL) and MgSO4, and then filtered through a plug of silica. To the ethereal solution was added TFA (8.5 μL, 0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv), and the mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The resulting salt was triturated with pentane (3 × 1 mL), and the volatiles were removed to provide the cyclization-allylation product (>95%) as a clear viscous oil (which could also be isolated as the mono-TFA salt).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.