ABSTRACT

Questionnaires were used to compare the characteristics and views of early retirees with those of doctors who were still working. Of doctors aged under 60 years, 88% were still working in medicine, 5% were fully retired and 7% were ‘returners’ (had retired and returned to do work). More women (8%) than men (4%) were fully retired. More GPs (13%) than hospital doctors (8%) had retired: male hospital doctors had a low retirement rate of 5.3%. More working doctors (28%) than fully retired doctors (20%) agreed that there were good prospects for improvement of the NHS in their specialty. More fully retired doctors (67%) and returners (67%) than working doctors (55%) referred to adverse health effects of working as a doctor. Early retirement decisions were motivated by the doctors’ views of what is happening in their own specialty and by adverse health effects that they attributed to their work.

KEYWORDS: Attitude of health personnel, physicians, workforce, medical, retirement

Introduction

A recent survey of consultant physicians in the UK found an average intended retirement age of 62 and 72% of these doctors did not intend to work beyond their contracted retirement age. Early retirement, and increasing numbers of doctors working less than full time, lessen the service benefit of increases in workforce numbers.1 Among GPs, 61% of those aged over 50 years are likely to retire within the next 5 years;2 this specialty in particular faces challenges in recruitment and retention.3,4

Commonly cited reasons for early retirement include wanting increased leisure time, and excessive work pressure.5 In the aforementioned survey,6 doctors cited similar reasons for retiring which included work pressure and excessive working hours. A recent systematic review of studies of motivations for early retirement suggested that high workload and burnout can lead to doctors’ earlier retirement.7 Given recent uncertainty around NHS contracts,8,9 and the UK’s impending exit from the EU,10 it is timely to update knowledge in this area with regard to UK-trained doctors.

Previously surveyed late-career doctors were predominantly aged over 60.5 For this paper we wanted to survey a sample of younger doctors aged under 60. This would allow a contemporaneous insight into the views and characteristics of a group of doctors who were thinking about retiring, or in some cases had already retired.

Our aim was to compare the characteristics and views of early retirees with those of doctors who are still working.

Methods

In 2016, the UK Medical Careers Research Group surveyed the UK medical graduates of 1983. Non-respondents were sent up to four reminders. Full methodological details are available elsewhere.11

The survey included structured, ‘closed’ questions and statements about employment. In designing the questionnaire we used two data sources: a) recurring themes in the literature and b) themes raised, in other surveys, by doctors arising in comments made to us.

Doctors were asked to indicate which one of seven phrases best described their current employment status: working full time in medicine; working part time in medicine; working full time outside medicine; working part time outside medicine; retired, not now working in medicine; ‘retired and returned’ for some medical work (‘returners’); other. We created two ‘employment status’ groups comprising doctors who: 1) were still in medicine and were under 60, and 2) had retired and were under 60 (including returners). We refer to these two groups as: 1) doctors still in medicine, and 2) early retirees.

Doctors still in medicine were asked: ‘Thinking of your career in medicine to date, how much have you enjoyed it overall?’ and retired doctors were similarly asked: ‘Thinking of your career in medicine, how much did you enjoy it overall?’ In each case, a 10-point scale was presented with two extremes: ‘I haven’t enjoyed / didn’t enjoy it at all’ (1) and ‘I have enjoyed / enjoyed it greatly’ (10); respondents were asked to give a score on this scale.

Doctors still in medicine were asked: ‘How much do you enjoy your current work?’ and doctors who had retired were asked: ‘How much did you enjoy your last post?’ In each case, a 10-point scoring scale was presented with two extremes: ‘I don’t/didn’t enjoy it at all’ (1) and ‘I enjoy/enjoyed it greatly’ (10).

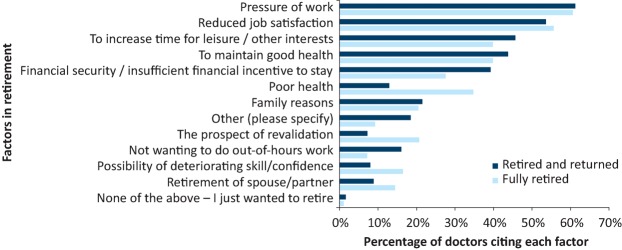

Retired doctors were also asked: ‘What were the circumstances of your retirement?’ with four options for reply (see Supplementary file 3). Finally, the retired doctors were asked ‘Which of these, if any, was a factor in your decision to retire when you did?’ The doctors were presented with thirteen factors (listed in Fig 1) and were asked to tick all that applied. Those who chose the factor listed as ‘Other’ were asked to provide further detail in text comment, which we analysed for content.

Fig 1.

Reasons for retirement, comparing fully retired doctors with retired and returned doctors.

All doctors were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements covering areas such as professional opportunities, working practices, NHS prospects and equal opportunities (see supplementary file 1 for details), using a five-point scale covering ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’, and ‘strongly disagree’. The questions selected were chosen for their relevance from a question bank of statements we have used over the last 25 years in our studies. These in turn were developed in part from the literature, in part from our own ideas of potentially important areas, and in part from themes raised with us by respondents in free text comments. For this paper we chose those statements which we hypothesised a priori may be related to retirement issues.

All doctors were also asked: ‘Do you feel that working as a doctor has had any adverse effects on your own health or wellbeing?’ with the options of Yes, No, or Prefer not to answer.

To facilitate comparison of responses from doctors in different specialties, we allocated a career specialty to each respondent using their job history as reported to us and additional information they provided about their specialist registration with the General Medical Council (GMC). We were unable to assign a small number of respondents to a single career specialty, either because we did not have sufficient data about the doctor’s career or because the doctor had worked in different specialties during their career. Respondents were grouped for analysis into these groups: hospital medical specialties, surgical specialties, paediatrics, emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, anaesthesia, radiology, clinical oncology, pathology, psychiatry, general practice / family medicine (GP).

We used χ2 tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests to explore differences in characteristics between doctors still in medicine and early retirees. We also compared differences in views between doctors still in medicine and early retirees, men and women, and doctors working in different career specialties.

This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service, following referral to the Brighton and Mid-Sussex Research Ethics Committee in its role as a multicentre research ethics committee (ref 04/Q1907/48 amendment Am02 March 2015). Under the terms of the ethical approval, and with the consent of the GMC, researchers were permitted to contact all doctors in the study cohort who had replied to at least one previous survey.

Results

Response rate

In 2014, we were able to contact 2690 (70%) of the original graduation cohort in 1983 of 3845 doctors (2379 men, 1466 women). Of these, 2106 responded (78.3%; 76.6% men, 81.0% women). The 1155 members of the cohort who we could not contact included 78 known to be deceased, 34 who declined to participate, 13 for whom no contact details could be found and 1030 who had not replied to any of our previous surveys. The median age of respondents at the time of the survey was 57 years for both men and women.

Current employment status

Of 2103 respondents who gave their employment status, 5.6% had retired (4.0% of men, 7.9% of women); 8.6% had retired and returned for some medical work (9.5% of men, 7.2% of women); 84.5% were still working in medicine (85.5% of men, 83.0% of women); 0.7% were working outside medicine; and 0.6% replied ‘other’. Therefore, 93.1% of respondents overall were still working in medicine (whether they didn’t retire or had retired and returned; 95.0% of men, 90.2% of women).

Characteristics of doctors still in medicine and early retirees

To ensure we were comparing doctors from a uniform demographic, we restricted analysis to doctors who were UK based and under 60. This reduced the sample from 2103 respondents to 1917 (Table 1), of which 88% were still working in medicine (89% of men, 86% of women); and 12% were early retirees (11% of men, 14% of women, a marginally significant difference, p=0.044).

Table 1.

Retirement status of doctors aged under 60, by specialty and gender

| All retired | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Not retired % (N) | All retired % (N) | Retired and returned % (N) | Fully retired % (N) | Total N (100%) |

| All responders | 87.7 (1681) | 12.3 (236) | 6.9 (133) | 5.4 (103) | 1917 |

| Men | 88.9 (1020) | 11.1 (127) | 7.4 (85) | 3.7 (42) | 1147 |

| Women | 85.8 (661) | 14.2 (109) | 6.2 (48) | 7.9 (61) | 770 |

| General practice | 87.1 (838) | 12.9 (124) | 7.2 (69) | 5.7 (55) | 962 |

| Hospital medicinea | 92.5 (727) | 7.5 (59) | 3.3 (26) | 4.2 (33) | 786 |

| GP men | 86.8 (465) | 13.2 (71) | 8.8 (47) | 4.5 (24) | 536 |

| GP women | 87.6 (373) | 12.4 (53) | 5.2 (22) | 7.3 (31) | 426 |

| Hospital mena | 94.7 (501) | 5.3 (28) | 3.0 (16) | 2.3 (12) | 529 |

| Hospital womena | 87.9 (226) | 12.1 (31) | 3.9 (10) | 8.2 (21) | 257 |

All retired (vs rest): men vs women χ21 = 3.8, p=0.052; GP vs hospital medicine χ21 = 12.8, p<0.001; 4 groups χ23 = 22.0, p<.001

Retired and returned (vs rest): men vs women χ21 = 0.8, p=0.36; GP vs hospital medicine χ21 = 11.8, p<0.001; 4 groups χ23 = 18.8, p<0.001

Fully retired (vs rest): men vs women χ21 = 15.6, p<0.001; GP vs hospital medicine χ21 = 1.8, p=0.182; 4 groups χ23 = 18.6, p<.001

aOmits psychiatry (see text)

We distinguished between doctors who were fully retired from medicine and doctors who had retired and returned to do some medical work (see methods section). A higher proportion of women than men were fully retired (p<0.001), but similar proportions of men and women had retired and returned (p=0.32).

Historically, in the UK psychiatrists can retire at an earlier age than other doctors with no actuarial reduction in pension.12 Psychiatrists in their 50s who hold mental health officer (MHO) status can retire from the age of 55 onwards.13 They are therefore a special group with much higher rates of younger retirement than other doctors. Among our respondents, 41% of psychiatrists were retired compared with 7.5% of other hospital doctors, combining all other hospital-based specialties. For this reason we omit psychiatrists from the hospital doctors shown in Table 1.

A higher percentage of GPs than hospital doctors had retired, a difference which was more pronounced in the retired and returned group than in the fully retired group (Table 1). Comparing the four groups of male GPs, female GPs, male hospital doctors and female hospital doctors, retirement rates differed, with male hospital doctors having the lowest retirement rate and contributing markedly to the observed differences.

Views on opportunities, practices and prospects

Differences were found between the responses of doctors who were retired, returners, and those still working in medicine for three of the nine statements (Table 2): ‘prospects for improvement of the NHS in my specialty’; ‘the NHS as a good equal opportunities employer for doctors from ethnic minorities’; and ‘the NHS as a good equal opportunities employer for doctors with disabilities’. In each case, fully retired doctors and returners tended to be less positive than doctors who were not retired, but percentage differences were modest.

Table 2.

Percentages of doctors who agreed or disagreed with each statement

| Not retired | Retired and returned | Fully retired | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | % Agree | % Disagree | % Agree | % Disagree | % Agree | % Disagree | Chi value | p-value (df=4) |

| Opportunities | 84.7 | 4.8 | 83.1 | 4.6 | 76.6 | 9.6 | 6.1 | 0.193 |

| Junior work | 53.6 | 27.1 | 55.7 | 28.7 | 59.0 | 30.8 | 4.8 | 0.307 |

| Nurse work | 50.7 | 31.7 | 52.0 | 28.8 | 49.4 | 32.9 | 0.6 | 0.962 |

| Improving specialty | 28.3 | 45.7 | 25.6 | 60.0 | 20.0 | 57.5 | 15.4 | 0.004 |

| GP men | 23.5 | 59.0 | 28.9 | 62.2 | 9.1 | 72.7 | 5.0 | 0.281 |

| GP women | 23.2 | 54.1 | 18.2 | 68.2 | 13.0 | 73.9 | 4.9 | 0.293 |

| Hospital mena | 32.4 | 33.7 | 20.0 | 53.3 | 27.3 | 36.4 | 2.7 | 0.613 |

| Hospital womena | 37.6 | 31.9 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 35.7 | 28.6 | 2.8 | 0.584 |

| Improving NHS | 24.0 | 53.8 | 21.3 | 62.3 | 19.3 | 59.0 | 4.6 | 0.330 |

| NHS women | 77.5 | 7.9 | 82.0 | 6.3 | 74.1 | 12.9 | 4.2 | 0.383 |

| NHS ethnicity | 69.6 | 7.6 | 77.5 | 7.8 | 56.2 | 15.1 | 11.7 | 0.019 |

| NHS disability | 30.3 | 18.5 | 40.2 | 18.3 | 27.9 | 30.9 | 10.5 | 0.033 |

| NHS illness | 27.0 | 45.2 | 24.8 | 46.0 | 21.7 | 49.4 | 1.4 | 0.848 |

Note: The percentages who chosen ‘neither’ are not shown in the table but can be calculated by subtracting the agree and disagree percentages from 100%.

The numbers on which the percentages shown are based can be found in supplementary file 1. See supplementary file 2 for a full list of the abbreviations used in this table.

aomits psychiatry (see text)

df = degrees of freedom

Considering the statement ‘There are good prospects for improvement of the NHS in my specialty’, more working doctors (28%) than fully retired doctors (20%) agreed (χ24 = 15.4, p<0.01), particularly among men (28% compared with 13%; χ24 = 13.1, p<0.05). This difference was not significant for women.

Considering the statement ‘The NHS of today is a good equal opportunities employer for women doctors’, more hospital returners (83.3%) than hospital doctors who were fully retired (72.4%) agreed (χ24 = 18.1, p<0.001). This difference was not significant among GPs.

Considering the statement ‘The NHS of today is a good equal opportunities employer for doctors from ethnic minorities’, among men, fewer fully retired doctors (51.4%) than returners (81.0%) agreed (χ24 = 12.8, p<0.05). This difference was not significant for women, and more hospital returners (90.0%) than hospital doctors who were fully retired (50.0%) agreed (χ24 = 28.5, p<0.001); this difference was not significant among GPs.

Adverse effects on doctors’ own health or wellbeing

All respondents were asked: ‘Do you feel that working as a doctor has had any adverse effects on your own health or wellbeing?’ More fully retired doctors (67.0%) and returners (66.9%) than doctors still working (55.3%) replied ‘yes’ (χ22 = 10.9, p<0.01; Table 3); this difference was significant among men, but not among women. More hospital returners (88.5%) than hospital doctors who were not retired (50.8%) replied ‘yes’ (χ22 = 17.7, p<0.001); this difference was not significant among GPs.

Table 3.

Adverse effects on health by specialty and gender

| Percentages who responded ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Do you feel that working as a doctor has had any adverse effects on your own health or wellbeing?’ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not retired | Retired and returned | Fully retired | Chi value | p-value (df=2) | ||||

| % | (n/N) | % | (n/N) | % | (n/N) | |||

| All | 55.3 | (893/1614) | 66.9 | (85/127) | 67.0 | (65/97) | 10.9 | 0.004 |

| Men | 52.5 | (512/976) | 68.4 | (54/79) | 57.5 | (23/40) | 7.7 | 0.022 |

| Women | 59.7 | (381/638) | 64.6 | (31/48) | 73.7 | (42/57) | 4.6 | 0.102 |

| General practice | 59.1 | (476/805) | 66.7 | (42/63) | 69.2 | (36/52) | 3.3 | 0.196 |

| Hospital medicinea | 50.8 | (354/697) | 88.5 | (23/26) | 68.8 | (22/32) | 17.7 | <0.001 |

| GP men | 57.9 | (256/442) | 70.7 | (29/41) | 62.5 | (15/24) | 2.7 | 0.264 |

| GP women | 60.6 | (220/363) | 59.1 | (13/22) | 75.0 | (21/28) | 2.3 | 0.312 |

| Hospital mena | 47.2 | (227/481) | 87.5 | (14/16) | 63.6 | (7/11) | 11.1 | 0.004 |

| Hospital womena | 58.8 | (127/216) | 90.0 | (9/10) | 71.4 | (15/21) | 4.9 | 0.085 |

Note: 69 responders are excluded from specialty breakdowns because their career specialty was unknown.

aomits psychiatry (see text)

df = degrees of freedom

Circumstances and reasons for retirement

The retired doctors were asked: ‘What were the circumstances of your retirement?’ More fully retired doctors (39.0%) than returners (20.2%) said that retirement had been unplanned and due to changes in personal circumstances (χ23 = 12.6, p<0.01; Supplementary file 3). There were no differences in responses between men and women doctors.

The retired doctors were asked ‘Which of these, if any, was a factor in your decision to retire when you did?’ (See methods section.) The most frequently cited factor was ‘pressure of work’ (61.0%) followed by ‘reduced job satisfaction’ (54.4%). More fully retired doctors (34.7%) than returners (12.9%) signified ‘poor health’ (Fig 1). More fully retired doctors (20.6%) than returners (7.2%) signified ‘The prospect of revalidation’. Fully retired doctors also scored ‘Possibility of deteriorating skill/competence’ and ‘Retirement of spouse/partner’ more than returners. More returners (16.0%) than fully retired doctors (7.2%) scored ‘Not wanting to do out-of-hours work’. More returners (39.2%) than fully retired doctors (27.6%) scored ‘Financial security / insufficient financial incentive to stay’. Comments were received from 22 of the 32 respondents who replied ‘other’: they described a variety of issues including the desire to work in another career area, perceived management issues and having MHO status (see above).

Significantly more hospital doctors (23%) than GPs (6%) retired because they did not want to do out-of-hours work (χ21 = 8.8, p<0.01). Within the retirees, those doctors who had retired and returned to do some medical work showed the greatest difference between hospital doctors and GPs, with 39% of hospital doctors compared with 5% of GPs having retired (and returned) because they did not want to do out-of-hours work (χ21 = 14.1, p<0.001). There were no other significant differences between GPs and hospital doctors for reasons for retirement.

Job enjoyment

The grouped median score for overall career enjoyment of doctors still working in medicine was 8.0, compared with 7.9 for fully retired doctors and 7.8 returners; for recent enjoyment the scores were 7.0, 7.2 and 6.9 respectively (Supplementary file 4). Neither overall nor recent enjoyment differed significantly between the three groups of doctors, between men or women, or between GP men, GP women, hospital men and hospital women.

Discussion

Main findings

More GPs had retired than hospital doctors, and male hospital doctors had the lowest rate of retirement in the cohort. No differences in career enjoyment were found when comparing retired and non-retired doctors. Retirement groups held similar views of career opportunities, support from juniors and nursing staff, the prospects for improving the NHS as a whole, and the NHS as a good employer in respect of doctors when ill. Some differences were found in the following areas: prospects for improvement of the NHS in the respondents’ own specialties, the NHS as a good employer for doctors from ethnic minorities, the NHS as a good employer for women doctors, and adverse effects on health of working as a doctor. Many hospital doctors (but not GPs) who had retired and returned had been motivated by the desire to avoid out-of-hours work.

Retired doctors had lower expectations of improvement to their specialty than non-retired doctors, a difference which was larger among GPs than among hospital doctors. Retired men and hospital doctors had a lower view of the NHS as a good employer for ethnic minority doctors than did non-retired doctors. Fully retired doctors were more likely than others to refer to adverse health effects of working as a doctor. The largest difference in this respect was found among male hospital doctors. Fully retired doctors were more likely than returners to have had an unplanned retirement due to changes in personal circumstances and were more likely to say that poor health and the prospect of revalidation were factors in their retirement.

Strengths and limitations

This independent, large-scale study of doctors who graduated from UK medical schools in 1983 had a high response rate of 78%. However, some non-response bias may have been present. Our large sample enabled us to focus our analysis upon a sample of doctors aged under 60.

We surveyed these doctors at a time when thoughts about retirement were likely to have been an important concern. Therefore, the timing of this survey has allowed insight into these doctors’ current thinking regarding retirement, as opposed to relying on their recall.

Comparison with existing literature

More GPs than hospital doctors had retired and retired GPs in particular had lower expectations of improvement to their specialty than working GPs. A study of older GPs found that 64% were likely to leave direct patient care within the next 5 years, and these GPs expressed ‘uncertainty regarding the future of general practice’.14 Other research with GPs has reported intentions to leave which rise sharply from the age of 52 years,15 less positive views about career prospects than hospital doctors16 and higher levels of burnout compared with hospital consultants.17

Retired doctors reported experiencing more adverse health effects from working as a doctor than working doctors. A recent survey of senior doctors also found more adverse health effects among retired doctors than working doctors.18 Fully retired doctors we surveyed reported that poor health and deteriorating competence were important factors in their retirement. In previous research, many UK doctors have raised concerns about stress and the effects of ageing upon stamina and energy levels.18 A review of research in the USA reported a decline in measured cognitive ability of 20% between the ages of 40 and 75 years.19

Fully retired doctors reported that the prospect of revalidation was an important factor in their retirement. Studies of GPs have found that this is frequently given as a reason for intending retirement.14,20,21

Conclusions and implications

Early retirees were similar to non-retirees in respect of several factors which may have been expected to be relevant to retirement decisions, namely their enjoyment of their work and their career opportunities, their support from juniors and nursing staff, their general view of prospects for improvement of the NHS and their treatment by the NHS when ill.

However, there were some observed differences in this cohort between doctors who were retired and those who were not, which may suggest short term policy changes and directions for future research.

Early retirement was more common among GPs, both men and women, and among women hospital doctors, than it was among male hospital doctors. Adverse health effects were more commonly reported among those not retired in the first three groups, and were reported least often among male hospital doctors still in medicine. Further research should investigate the interplay between perceived risk to health of being a doctor and attitudes towards retirement, and what can be done to minimise risks to health.

Among GPs, those who were retired, both men and women, had a more negative view of the prospects for improvement of the NHS in their specialty than did doctors who were not retired. In part this may be due to current pressures on general practice consequent to low take-up of training places. However, there is scope for research to examine the future model of general practice and the career paths and options for doctors at all stages of their careers.

The desire to avoid out-of-hours work was a motivator for hospital doctors both to fully retire and to ‘retire and return’. Contractual changes to allow older doctors to opt for fewer antisocial hours would encourage some to remain in medicine for longer.

Policy initiatives which seek to encourage doctors to remain working in medicine until normal retirement age should address these areas.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at http://futurehospital.rcpjournal.org :

S1 – Numbers of doctors who agreed or disagreed with each statement: by specialty, gender, and retirement status

S2 – Statements used in the questionnaire and abbreviations in Table 2

S3 – Retirement circumstances by retirement status

S4 – Job enjoyment: a) Career enjoyment b) Current / last job enjoyment, comparing doctors still in medicine with early retirees

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians Underfunded, underdoctored, overstretched: The NHS in 2016. London: RCP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson J, Checkland K, Coleman A., et al. Eighth National GP Worklife Survey. PRUComm, 2016. www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/39031810/FULL_TEXT.PDF [Accessed 24 April 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS Securing the future GP workforce – delivering the mandate on GP expansion: GP Taskforce final report. NHS, 2014. www.pulsetoday.co.uk/download?ac=9243 [Accessed 24 April 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert T, Goldacre M. Trends in doctors’ early career choices for general practice in the UK: Longitudinal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith F, Lachish S, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Factors influencing the decisions of senior UK doctors to retire or remain in medicine: national surveys of the UK-trained medical graduates of 1974 and 1977. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians Census of consultant physicians and higher specialty trainees in the UK 2014–15. London: RCP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silver MP, Hamilton AD, Biswas A, Warrick NI. A systematic review of physician retirement planning. Hum Resour Health 2016;14:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS employers Junior doctors’ 2016 contract. 2016. www.nhsemployers.org/your-workforce/need-to-know/junior-doctors-2016-contract [Accessed 7 April 2017].

- 9.Lambert TW, Smith F, Goldacre MJ. Why doctors consider leaving UK medicine: qualitative analysis of comments from questionnaire surveys three years after graduation. J R Soc Med 2018;111:18–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torjesen I. Four in 10 European doctors may leave UK after Brexit vote, BMA survey finds. BMJ 2017;356:j988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldacre M, Lambert T. Participation in medicine by graduates of medical schools in the United Kingdom up to 25 years post graduation: National cohort surveys. Acad Med 2013;88:699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.British Medical Association Pensions advice for Mental Health Officers (MHO). BMA, 2017. www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/pensions/mho-pension-advice [Accessed 19 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal College of Psychiatrists Response to the Health Committee’s Inquiry into Workforce needs and planning for the health service. London: RCPsych, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sansom A, Calitri R, Carter M, Campbell J. Understanding quit decisions in primary care: a qualitative study of older GPs. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher E, Abel GA, Anderson R, et al. Quitting patient care and career break intentions among general practitioners in South West England: findings of a census survey of general practitioners. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert TW, Smith F, Goldacre MJ. Perceived future career prospects in general practice: quantitative results from questionnaire surveys of UK doctors. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e848–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halliday L, Walker A, Vig S, Hines J, Brecknell J. Grit and burnout in UK doctors: a cross-sectional study across specialties and stages of training. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith F, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Adverse effects on health and well-being of working as a doctor: views of the UK medical graduates of 1974 and 1977 surveyed in 2014. J R Soc Med 2017;110:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patchen Dellinger E, Pellegrini CA, Gallagher TH. The aging physician and the medical profession a review. JAMA Surgery 2017;152:967–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.British Medical Association National survey of GP opinion 2011. London: BMA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dale J, Potter R, Owen K, Leach J. The general practitioner workforce crisis in England: a qualitative study of how appraisal and revalidation are contributing to intentions to leave practice. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]