Transgender, or trans, describes an incongruence between an individual’s sex assigned at birth and their current gender identity, or their sense of being male, female, both, or neither.1 Individuals with an alignment between their assigned sex and gender identity are considered cisgender. The transgender population represents a spectrum of gender identities and expressions.2 Transgender women, or male-to-female (MTF) individuals, were assigned male at birth and currently identify as women or female; transgender men, or female-to-male (FTM) individuals, were assigned female at birth and now identify as men or male.3 Some, but not all, transgender people desire gender-affirming medical interventions such as cross-sex hormone therapies, gender-affirming surgeries, and other body modifications.1 The number of adults who identify as transgender in the U.S. is approximately 1.4 million;4 however, the absence of a consistent definition for the term transgender and the social stigma associated with transgender identities likely contribute to under-reporting.5 The term transgender is part of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) acronym that represents both sexual orientation and gender identity groups.1 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and sometimes queer are used to express sexual orientation, which includes sexual and/or romantic attractions to people of different gender.3 Transgender people have a range of sexual orientations, including but not limited to gay, bisexual, asexual, queer, and heterosexual,1 and can be attracted to cisgender men/women and/or other transgender people.

Transgender people in the U.S. experience social disadvantages such as living below the poverty level,2,6 a higher rate of homelessness,2 sexual and physical assaults,2,7 bullying,2 unequal treatment or service in public accommodations,8,9 and they are three times as likely to be unemployed than the general public.2 They endure discrimination and systematic oppression by healthcare professionals and within healthcare settings.2 Discriminatory experiences include inappropriate care, care refusal, and mistreatment by health providers.10,11

Transgender-related discrimination is associated with negative psychological outcomes, such as increased rates of clinical depression and anxiety,12 self-harming behaviors,9 drug and alcohol use and abuse,2,13 and suicide.14 Discrimination likely contributes to the 40% lifetime suicide attempt rate in transgender-identified adults, a prevalence that far exceeds those in the general U.S. population (4.6%) and in LGB communities (10–20%).2,12,15 With the release of Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) in 2010, the U.S. federal government recognized the need to address the community’s health inequities and discrimination experiences by designating transgender health as a national priority.16 Reisner and colleagues17 postulate that the health inequities experienced by transgender people may be reduced by using gender-affirming approaches in the delivery of healthcare. Gender affirmation is a multidimensional and dynamic social process that affirms and acknowledges the gender identity and/or expression of transgender individuals.18

Prior to HP2020, the discrimination transgender people experienced in healthcare settings was well documented;1 however, since its release in 2010, little is known about their experiences. A year after announcing the HP2020 goals, the National Academy of Medicine (NAOM), formally the Institute of Medicine, designated transgender health as a research priority and called for more research addressing the disparities they experience in healthcare.1 The NAOM recommended exploring the healthcare experiences and barriers transgender people face to equitable healthcare, as these barriers can profoundly affect their healthcare utilization and well-being. The purpose of this literature review was to respond to the NAOM call and to contextualize the experiences of trans adults interfacing with healthcare in the U.S. Guided by a modified gender affirmation framework,18 this review sought a deeper understanding of the challenges encountered within healthcare environments and the motivating factors and barriers met when attempting to access healthcare for transgender adults in the U.S. Findings will help prioritize future research directions for transgender people and healthcare providers, aid in the development of interventions, and guide current and future public health initiatives and policies addressing the health of the transgender population.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

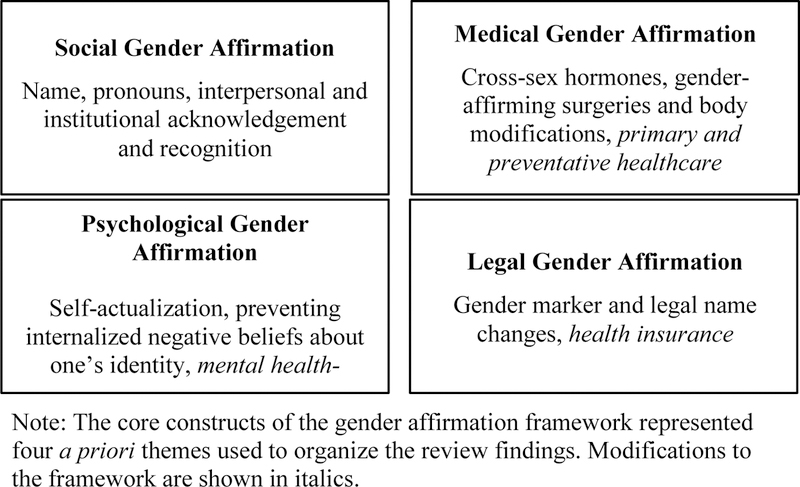

Gender affirmation, a critical element of the health and well-being of trans individuals, is conceptualized as a social process of being affirmed and supported in one’s gender identity, expression, and/or role.18,19 The gender affirmation framework was developed to explore the sexual and body modification behaviors of transgender women of color, where it was discovered that in the absence of gender affirmation, the women would engage in risky health behaviors.18 The framework integrates components of intersectionality,20 objectification theory,21 and the identity threat model of stigma.22 It is composed of four constructs: social (name, pronouns, interpersonal and institutional acknowledgement and recognition), medical (gender-affirming medical interventions such as cross-sex hormonal therapy, surgeries, and other body modifications), psychological (self-actualization and preventing internalized negative beliefs about one’s identity), and legal (gender marker and legal name changes) gender affirmation.18 Use of the framework is recommended when studying transgender individuals,18,19 and its constructs have been shown to influence healthcare utilization among transgender adults.11 This review used a modified version of the framework (Figure 1); the conceptualizations of the original constructs were broadened to comprise aspects related to healthcare, such as the incorporation of “primary and preventative healthcare” within medical gender affirmation, “mental-health related services” under psychological gender affirmation, and legal gender affirmation includes “health insurance”.

Figure 1.

Modified gender affirmation framework

METHODS

To better understand the healthcare experiences of transgender people, an integrated mixed research literature review was selected. This approach allowed for inclusion of all study designs and thus, produced empirical findings representing the broadest possible understanding of the literature.23 An integrated design was applied because the studies included were in a common domain addressing a similar research purpose, and they can confirm, extend, or refute one another when assimilating research findings.23

This review of peer-reviewed literature covered a 6.5-year period from 2011 through June 2017 and followed the release of HP2020. A systematic approach was used to identify terms and concepts (Table 1) searched in four databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsychINFO, PubMed, and SocINDEX. Studies included were: 1) peer-reviewed journal publications; 2) any study design that provided data about the experiences of transgender adults accessing and utilizing healthcare within the U.S.; 3) about transgender adults older than 18 years-old; 4) published in 2011 through June 2017; and 5) published in English. Studies excluded were those that: 1) did not disaggregate findings about transgender individuals living in the U.S. from those in other countries; 2) did not disaggregate findings about transgender individuals from those of LGBQ adults; 3) were focused on transgender youth; 4) did not distinguish findings of transgender individuals under 18 years-old from those over 18 years-old; 5) focused on clinical outcomes; 6) concentrated on healthcare curricula; 7) were grey literature (e.g., conference abstracts, presentations, government publications, and dissertations/theses), commentaries, editorials, or literature reviews. References from literature reviews were assessed and those references meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this review.

Table 1.

Search terms and concatenation of terms utilized (n=23)

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature | transgender[MH] OR transgender[MJ] OR transgender[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR transsexual[TI] OR transgenders[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR trans[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “trans health”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR transmen[TI] OR transwomen[TI] |

| PsychINFO | transgender[MA] OR transgender[MJ] OR transgender[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR transsexual[TI] OR transgenders[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR trans[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “trans health”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR transmen[TI] OR transwomen[TI] |

| PubMed | (“transgender persons”[MeSH] OR “health services for transgender persons”[MeSH] OR transgender[title] OR transgendered[title] OR transsexual[title] OR transgenders[title] OR transgendered[title] OR trans[title]OR “transgender healthcare”[title] OR “transgender healthcare”[title] OR “trans health”[title] OR “trans healthcare”[title] OR “trans healthcare”[title] OR transmen[title] OR transwomen[title]) AND (healthcare[tiab] OR “healthcare”[tiab] OR “access”[tiab] OR utilization[tiab] OR “barriers”[tiab] OR “healthcare services”[tiab] OR “healthcare services”[tiab] OR “access to care”[tiab]) |

| SocINDEX | transgender[DE] OR transgender[SU] OR transgender[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR transsexual[TI] OR transgenders[TI] OR transgendered[TI] OR trans[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “transgender healthcare”[TI] OR “trans health”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR “trans healthcare”[TI] OR transmen[TI] OR transwomen[TI] |

Note. Keywords and MeSH are specific to each database. AB: abstracts; DE: subjects; MA: Mesh subject heading; MeSH: medical subject headings; MH: exact subject heading; MJ: word in major subject heading; SU: subject terms; TI: title; tiab: title and abstract.

Search Outcome

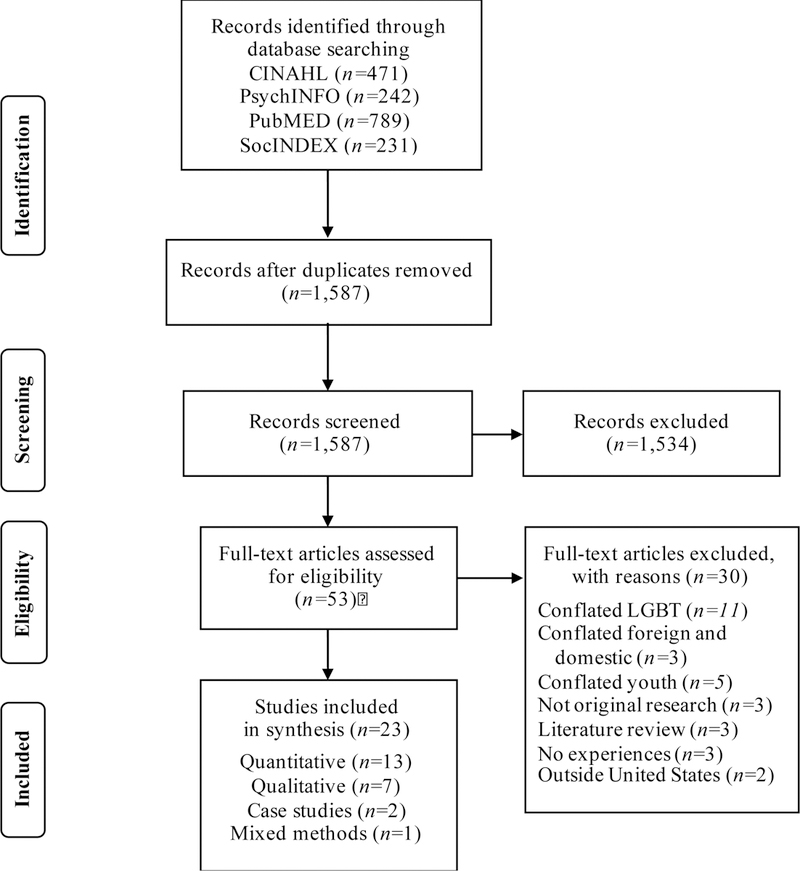

Figure 2 provides a PRISMA diagram that illustrates the screening, eligibility, and selected manuscripts for inclusion. A total of 1,733 articles were obtained and all abstracts were imported into EndNote™ X8; 1,415 articles remained after duplicates were removed. Of the remaining articles, EndNote™ X8 was used to scan titles and abstracts for exclusion and inclusion criteria. Fifty-three articles were retained for full-text review. Following the Matrix Method,24 we abstracted data from each article using a structured abstracting spreadsheet with 12 topics: author, title, year of publication, journal, study design, sampling method, data collection date, sample characteristics, findings, transgender definition, study limitations, and gender affirmation construct. Additionally, each article’s references were hand-searched to identify any articles that met our inclusion criteria; however, no additional articles were identified.

Figure 2:

PRISMA flow diagram

The final sample included 23 articles. All articles meeting the inclusion criteria were included regardless of quality or methodological-related concerns; however, all 23 articles were scrutinized, and any methodologic critiques are reported within the findings section. Due to the significant heterogeneity in both study design, transgender communities studied, and outcomes measured across the sample, a robust meta-analysis or statistical analysis was impossible to conduct. Instead, a thematic analysis was conducted to detect patterns and regularities, inconsistencies, and identify the circumstances surrounding healthcare access and utilization of transgender adults.25 The constructs of the gender affirmation framework represented four a priori themes used to organize the findings. The first author performed the initial data abstraction, including the identification of the gender affirmation construct(s) for each article meeting the inclusion criteria. After, the first and last authors met to discuss each article’s associated gender affirmation construct; if there was a disagreement, a third reviewer (SLR) resolved the disagreement.

RESULTS

Of the 23 articles included in this review (Table 2), 13 (57%) were quantitative studies, seven (30%) were qualitative, two (9%) were case studies, and one was a mixed methods study. Apart from a secondary analysis, the remaining qualitative studies used purposive sampling to recruit a range of 10 to 55 participants, mainly transgender women (77%), where only one interview was conducted per participant. Two qualitative studies collected data from 12 focus groups. All articles produced findings that fit into at least one of the four a priori themes derived from the gender affirmation framework.

Table 2.

Characteristics of articles reviewed (n=23)

| Author (Year) | Focus | Data Collection | Sampling Method | Sample (N) | Geographic Location | Trans Defined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Studies | ||||||

| Cicero and Black (2016) | An emergency room experience | 2011 | Purposive | FTM (1) | Southeast U.S. | Yes |

| Shukla et al. (2014) | Barriers to healthcare | Purposive | MTF (1) | No | ||

| Mixed Methods | ||||||

| Radix et al. (2014) | Satisfaction and healthcare utilization | 2013 | Purposive | MTF (26) FTM (11) Trans (9) |

New York City, NY | Yes |

| Qualitative | ||||||

| Brown (2014) | The healthcare concerns of transgender inmates | Convenience | MTF (125) Trans (3) |

24 statesb | No | |

| Hagen and Galupo (2014) | Gendered language in healthcare | Purposive, convenience | MTF (9) FTM (11) |

12 statesc | No | |

| Poteat et al. (2013) | Stigma in transgender healthcare | 2011 | Purposive | MTF (30) FTM (25) |

Mid-Atlantic | Yes |

| Roller et al. (2015) | Engagement in healthcare | Purposive | MTF (6) FTM (19) |

U.S. | Yes | |

| Sevelius et al. (2014) | Barriers and facilitators to healthcare engagement and retention for trans women living with HIV | Purposive | MTF (38) | San Francisco, CA | No | |

| Wilson et al. (2013) | Access to HIV-related care for African American trans women living with HIV | Purposive | MTF (10) | Alameda County, CA | No | |

| Xavier et al. (2012) | Healthcare access | 2004 | Purposive | MTF (32) FTM (15) |

VA | Yes |

| Quantitative | ||||||

| Bradford et al. (2013) | Social determinants of health and experiences of transgender-related discrimination | 2005–2006 | Purposive | MTF (229) FTM (121) |

VA | Yes |

| Cruz (2014) | The postponement of primary curative care | 2008–2009a | Convenience | MTF (2427) FTM (1867) |

U.S. | Yes |

| de Haan et al. (2015) | Barriers to care and non-prescribed hormone use | 2010 | Convenience | MTF (314) | San Francisco, CA | Yes |

| Jaffee et al. (2016) | Delayed healthcare, perceived provider knowledge, and discrimination | 2008–2009a | Convenience | MTF (2068) FTM (1418) |

U.S. | Yes |

| Jaffer et al. (2016) | Adequacy of care within jail | Purposive | MTF (25) FTM (2) |

New York City, NY | No | |

| Kattari and Hasche (2015) | Influence of age on experiences of healthcare discrimination, harassment, and victimization | 2008–2009a | Convenience | Trans (5885) | U.S. | Yes |

| Kattari et al. (2017) | Influence of (dis)ability on discriminatory experiences when accessing social services | 2008–2009a | Convenience | Trans (6456) | U.S. | |

| Kattari et al. (2015) | Race/ethnicity differences in experiences of healthcare discrimination | 2008–2009a | Convenience | Trans (6454) | U.S. | No |

| Nemoto et al. (2015) | Unmet healthcare needs | 2000–2001; 2004–2006 | Purposive, convenience | MTF (235) | San Francisco and Oakland, CA | Yes |

| Shipherd et al. (2012) | Utilization of Veterans Health Administration health services |

2008 | Convenience | MTF (141) | U.S. | Yes |

| Shires and Jaffee (2015) | Discrimination experienced in healthcare | 2008–2009a | Convenience | FTM (1711) | U.S. | Yes |

| White Hughto et al. (2016) | Geographic and individual differences in healthcare access | 2008–2009a | Convenience | Trans (5831) | U.S. | Yes |

| Whitehead et al. (2016) | Primary healthcare utilization | 2014 | Convenience | Trans (169) | U.S. | No |

Note. Individuals assigned male at birth but identify as something other than male are categorized as MTF; FTM represents those persons that were assigned female at birth but identify as something other than female; and the term trans is used if researchers grouped all trans people together or did not identify the trans subgroup or sex assigned at birth. Study participants may have used other terminology when describing themselves.

National Transgender Discrimination Survey secondary analysis

Located in AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, IA, ID, IN, KY, MA, MI, NV, NY, OK, OR, PA, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WA, WI

CA, MA, MD, MI, MN, NC, NJ, NV, NY, RI, TX, VA

Of the quantitative studies, seven were secondary analyses of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS), a study that explored the lifetime experiences of discrimination for 6,456 trans adults in the U.S.26 The study used grassroots approaches for recruitment, and data were collected in 2008–2009.26 The remaining quantitative and mixed methods studies used convenience and purposive samples of less than 350 participants, primarily consisting of transgender women (87%). Moreover, 30% of the quantitative studies grouped all transgender participants together for their analyses without disaggregating gender identity groups. The case studies provided data on a transgender man and woman.

Data collection periods and definitions for the term transgender varied across the sample. Data were collected before and after the release of HP2020, and seven studies (30%) did not report their data collection periods. Eight studies (35%) did not define the word transgender. Of the remaining studies, three used the NTSD definition, 11 included gender expression and/or presentation, and one described transgender as a sexual identity.

Social Gender Affirmation

Social gender affirmation is a key component in healthcare access, utilization, and therapeutic relationships with healthcare professionals and systems, but in its absence, transgender adults experience stigma, prejudice, and discrimination.27–35 Non-affirming public spaces create life-threating conditions and barriers to healthcare for visibly gender nonconforming transgender women, particularly those of color.31,33,34 Three qualitative studies provided insight into how African American and Black transgender women prioritized safety over risking their lives traveling to healthcare appointments.31,33,34 The social context within healthcare settings also influence healthcare utilization. Transgender women reported avoiding HIV-related appointments because of fear that their HIV serostatus would be publicly revealed if they encountered a peer or were seen entering a HIV-related care facility.31,33

Check-in and registration in healthcare settings were challenging processes where transgender adults encountered insensitive staff and structural obstacles, such as electronic health records and patient intake forms.27,28,31,34 For example, a transgender man checking-in to an emergency room disclosed that he was transgender, and the gender marker on both his driver’s license and existing electronic health record reflected female, his sex assigned at birth.27 The employee and several colleagues verbally assaulted him by repeatedly referring to him as a woman, even after he voiced his objection; as a result, he left without being evaluated.27

Transgender adults have a variety of reactions when patient intake forms use the terms sex and gender interchangeably, as well as when forms feature binary distinctions for sex/gender.28–30 Trans participants in multiple studies reported having to interpret whether the facility sought information about their gender identity, or their sex.28–30 In these studies, trans participants described feeling invisible when forms contained binary distinctions for sex/gender; however, other participants noted feeling affirmed by the dichotomous option because they did not identify as a transgender man/woman, but as a man/woman.28 Further complications arise when trans individuals provide their legal name, current name, and pronouns on intake forms.28,29 Staff and clinical providers may exhibit uncertainty about which name or pronoun to use, particularly when the physical presentation and gender identity of the trans patient aligns with traditional conceptualizations of gender.28,29 For instance, a FTM study participant shared, “If I mark trans as my gender on a form but it does not ask (FTM/MTF) because I pass extremely well as male they tend to assume I’m a transgender woman.”28(pp24) Transgender participants also expressed fear when disclosing their gender identity because they expected or anticipated discrimination and suboptimal or inappropriate care.28,29,32,36,37 Despite the abundance of non-affirming experiences in healthcare settings, more than half of the sample interviewed by Hagen, Galupo 28 reported feeling seen and respected as a complete person by the affirming language and communication approaches used by Planned Parenthood.

One study-specific limitation is related to social gender affirmation. Jaffer and colleagues38 sought to improve the quality of healthcare for incarcerated transgender adults in the New York jail system. Eligible participants were identified by cross-sex hormone use documented within pharmacy records. This sampling approach excluded those who did not want or desire cross-sex hormones, thus their health needs and healthcare experiences were not evaluated. This limitation also impacts findings reported in medical gender affirmation.

Medical Gender Affirmation

Access to gender-affirming medical interventions is a priority for many transgender adults.29–31,34,36,37,39–41 The majority of articles reviewed revealed that cross-sex hormones, an intervention requiring lifelong medical monitoring and healthcare interactions, was discussed most often. Cross-sex hormones were described as a fundamental component in a trans person’s quality of life as it affords the individual greater social acceptance and reduces the threat of harassment and violence.30,31,33,34,38,40,42 Two qualitative studies contextualized the complicated relationship transgender women living with HIV have with cross-sex hormones.31,33 The women expressed a desire to be seen as cisgender women, however their motivation to access and use cross-sex hormones varied between increasing their safety in public spaces and earning higher wages for those engaged in survival sex work.31,33 The women involved in transactional sex expressed prioritizing cross-sex hormones over HIV care due to cost; moreover, they agreed that the integration of cross-sex hormone therapy with their HIV care provider would facilitate compliance in maintaining adherence to their antiretroviral therapy for viral load suppression.31,33

Trans adults attempting to access gender-affirming medical interventions and primary and preventative care experience numerous challenges and barriers, such as the scarcity of available, knowledgeable, and affirming clinicians.29–34,38–44 Trans people scour the internet and tap into social networks inquiring about supportive and competent clinicians.29,30 They use various strategies when encountering providers who are not proficient in gender-affirming care.29–31,33,34,37,40 Many arrive at appointments knowledgeable and informed about hormone therapy regimens and required medical monitoring,29–31,34 and some travel great distances for knowledgeable providers.30,34,42 Researchers discovered that transgender adults living in rural areas were more than three times as likely to drive over an hour to their primary care providers than their LGB cisgender peers.44 However, affirming providers are not always accessible, leaving some trans adults feeling powerless.29 To illustrate this point, a transgender woman in one study shared, “I did walk away from there a couple of times – always ended up going back because there’s nowhere else to go – so I always wind up going back.”29(pp28)

Many transgender people are refused primary and preventative care and gender-affirming medical interventions due to their gender identity and expression.27,29–31,33,34,36,42,45–49 Data from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study revealed that more than 25% of the sample were unable to obtain gender-affirming medical interventions and nearly half of those assigned female at birth were unable to access gynecological care.39 When trans adults are unable to access cross-sex hormones from a clinical provider, they turn to friends, the streets, and the internet.31,34,41,42 De Haan and colleagues41 reported that nearly half of the trans women did not receive cross-sex hormones from a provider, and 36% used non-prescribed cross-sex hormones because they were unable to access a prescribing provider. Trans individuals residing in correctional settings also face barriers to such interventions,38,40 with some women attempting or completing autocastration due to lack of access to surgical treatments while imprisoned.40

Transgender adults endure discrimination in healthcare because of their gender identity or gender expression.27–31,33,34,36,38–42,44–49 Transgender adults experience higher rates of discrimination when healthcare providers are aware of their patient’s gender identity.36,48 White Hughto and colleages49 discovered a positive association between care refusal in trans adults who were older; assigned male at birth; Native American, multi-racial or other racial/ethnic minority; had low income; and discrimination-related care avoidance. When holding these factors constant, trans residents in southern and western states had increased odds of experiencing care refusal; moreover, states with a greater percentage of Republican voters increased the odds associated with care refusal.49

Healthcare access and utilization are impacted by transgender-related discrimination. Previous encounters of discrimination and knowledge of other transgender adults’ discriminatory experiences precipitate transgender adults avoiding and/or delaying healthcare.27–31,33,34,36,39,42,45,48 Transgender adults who reported having to teach their providers about transgender identities, were four times as likely to delay care as compared to those where provider education was not needed.45 Researchers studying healthcare utilization of transgender veterans discovered that most sought care at non-Veterans Health Administration facilities because they were apprehensive about provider-based discrimination.37 Researchers discovered that transgender people of color reported a significantly higher prevalence of discrimination when accessing doctors and hospitals, emergency rooms, and ambulances/emergency medical technicians than their white trans counterparts.47

Limitations from two studies impact the findings reported within medical gender affirmation. In a secondary analysis of unsolicited correspondence to the editor of a transgender prison journal, Brown40 did not describe the data analysis methods; therefore, the trustworthiness and credibility of the findings cannot be assessed. Additionally, in a study that explored differences across age groups and discrimination, Kattari et. al.47 combined physical and verbal assaults, along with denial of equal treatment or services under the larger umbrella term “discrimination within healthcare settings.” This approach allowed for a larger sample for analyses than would have been achievable if they had considered different types of discrimination as distinct categories. This aggregation may have influenced the chi-squared analyses because with large samples, very small associations will yield significant results, raising the likelihood of an analysis being significant but not clinically meaningful.

Psychological Gender Affirmation

Transgender adults encounter barriers when accessing mental health-related services creating unmet mental health needs; further, when they can access care, they experience non-affirming clinicians.31,33–35,37,39,42,46 Nearly half of the transgender women interviewed by Sevelius and colleagues31 reported currently or previously utilizing mental health services, and focus group participants explained that psychotropic medications were more accessible than psychotherapy, as some clinicians had a one- to two- year waiting period for therapy appointments. In the same study, a 49-year-old Black transgender woman described the influence of stigma when accessing care,

“We as Black trans women don’t want to address mental health because we think it’s an ugly thing. But yet, we transition and we still have anxiety and we still have PTSD; we still have domestic violence issues; we still have all that. But yet, it’s not being addressed. We’re so busy addressing the hormones and the trans thing and the HIV that we’re leaving out everything else. We’re not dealing with the total package, the total person.”31(pp11)

When transgender adults access care, they encounter mental health professionals and facilities using non-affirming approaches, such as providers believing that being transgender is a form of a mental illness,34,35,37,46 resulting in some trans persons avoiding mental health services altogether.33,34,37 To mitigate these access issues, transgender study participants suggested the integration of mental health services within a multidisciplinary and comprehensive trans health center.42

One study found that African American transgender women living with HIV experienced clinicians providing inappropriate referrals to healthcare services, such as substance abuse programs and support for sex workers, which was based on stigma-laden assumptions about their transgender identity, race, and HIV serostatus.33 For those seeking treatment for alcohol and substance abuse, programs often house transgender clients based on their sex, creating unwelcoming and unsafe conditions.31,35 Researchers discovered that transgender adults with a disability or impairment (socioemotional, physical, learning, or multiple disabilities) were significantly more likely to experience discrimination when accessing social services such as rape crisis centers, domestic violence shelters, and drug treatment programs than those trans people without disabilities.35 While increases in income and age reduce the likelihood of experiencing discrimination, being a racial/ethnic and sexual minority increase the odds of discriminatory experiences.35 For example, Latino individuals were two to four times more likely to experience discrimination accessing social services than white trans adults; bisexual and queer transgender adults were 5 and 3.5 times more likely, respectively, to experience discrimination at a drug treatment program and sexual minorities were 1.5 times more likely to experience discrimination at mental health centers than their heterosexual transgender counterparts.35

Legal Gender Affirmation

Health insurance companies deny benefits to many transgender adults for routine preventative care and medically necessary procedures when the care is not aligned with the gender marker on their insurance policy, even though the procedures are medically appropriate for their current anatomy.28,30,34,39,42 Similarly, insurance companies also deny coverage for medically necessary gender-affirming medical interventions.28,30,34,39,42 For example, after receiving an abnormal Pap smear result, a transgender man chose to delay follow-up care, and cited that his insurance company would only pay for a hysterectomy if he was diagnosed with cervical cancer.30 To eliminate these healthcare barriers, transgender study participants suggested the incorporation of legal support for name/gender marker changes within trans healthcare center.42

Several analyses of NTDS data indicated that trans-related discrimination and healthcare postponement were associated with the type of health insurance coverage.36,48 Trans men with public health insurance were more than twice as likely to report discrimination than those with private health insurance.48 Kattari and Hasche46 discovered that relative to those transgender adults without insurance, trans adults with private and those with public insurance were more likely to report higher rates of harassment, 14 and four times respectively. While these studies provided valuable insight, the associations reported among health insurance, discrimination, and care postponement may be misleading because discrimination and care postponement were lifetime measures, whereas study participants provided their health insurance details at the time of the survey.36,46,48

Discussion

This integrated mixed research literature review, framed by the gender affirmation framework, sought to contextualize the experiences of transgender adults interfacing with healthcare. Evidence from this review indicates that transgender adults experience numerous obstacles when accessing healthcare such as unsafe public and healthcare spaces, lack of knowledgeable clinicians, and restricted health insurance benefits for medically necessary care. During healthcare utilization, they encounter gender non-affirming healthcare professionals and clinicians; experience barriers to gender-affirming medical interventions, primary and preventative care, and mental health-related services; and endure discrimination and healthcare refusal. Our findings are consistent with the literature published prior to HP2020, which is not surprising given that over half of the articles reviewed collected data before its release, including seven NTDS secondary analyses. These articles, representing over half of the quantitative sample, explored discrimination in healthcare and may drive the characterization of discrimination described in this review. However, by using an integrated approach we discovered that discrimination was reported across all study designs. Moreover, our findings offer further evidence that the gender affirmation framework can be used to understand healthcare utilization and the health behaviors of transgender adults. The exclusive focus on using framework’s constructs as a priori themes did not obscure other potentially important factors or emerging themes.

While discriminatory experiences were frequently endorsed by transgender adults, data collection periods cannot be used as a proxy in determining when the events occurred. For example, the NTDS measured lifetime discriminatory experiences and the remaining studies reviewed did not elicit the chronology for the negative healthcare experiences. With the rise in public awareness, increase in time devoted to transgender health within healthcare curricula, and advancements to the standards of care for transgender individuals, it is important to assess their impact on improving the healthcare experiences of transgender adults. Researchers should consider framing interview and survey questions to identify the period for when such events occurred, including delineating the timeframe for exposures and outcomes. Additionally, apart from two studies, study participants perceived their experiences of discrimination were a direct result of their transgender identity and not a consequence of their race/ethnicity, class, or (dis)ability; yet, the NTDS data showed that these characteristics also influenced the prevalence of discrimination reported.

The sample synthesized did not always describe the health services sought or the type of provider encountered. When it was reported, most study participants were attempting to access gender-affirming interventions. Transgender adults, like their cisgender counterparts, interact with the healthcare system for a myriad of reasons unrelated to these interventions such as oral health, physical therapy, and sexual and reproductive health needs. Future studies are recommended to explore the variety of health services, settings, and professionals encountered.

The majority of data reviewed represented the experiences of transgender women, particularly trans women of color, from small purposive and convenience samples, leaving many trans communities underrepresented and unexplored such as transgender men and individuals who do not self-identify with the term transgender. However, the search terms used to identify articles included in this synthesis may have also contributed towards the underrepresentation of diverse transgender subgroups. More research exploring the role of ethnicity, geographic region, socioeconomic position, sexual orientation, etc. is needed.

The studies reviewed used an array of definitions for the term transgender; introducing selection bias that contributes to the gaps in knowledge regarding the healthcare experiences transgender subgroups. For example, the use of medical records to identify transgender adults who are using cross-sex hormones excludes those who are unable to access hormones and those who are not pursing the gender-affirming medical intervention. These methodological concerns are also representative of the larger body of transgender health literature; 5,50 accordingly, research is needed to illuminate the healthcare experiences of transgender subgroups and reflects the diversity of gender identity and expression, and demographic characteristics found within the transgender population. Additionally, this review uncovered the impact on healthcare utilization for transgender women who do not visually conform to social and cultural gender norms. This type of gender nonconformity may influence healthcare experiences for other transgender communities, thus studies are needed which integrate and examine the significance of gender (non)conformity as a visible marker of one’s transgender status.

Nursing Implications for Practice and Research

Positive and affirming healthcare encounters are needed to help improve the health of transgender people. Nurses, other health professionals, and health professions students need to learn about what it means to be transgender, what are the relevant concerns/issues in the competent administration of healthcare to transgender individuals. Both didactic and clinical content on transgender health needs to be included in curricula beginning with fundamental skills such as therapeutic, gender-affirming communication through health assessment, and beyond. Furthermore, advanced practice nursing programs are in a unique position to increase the number of clinical providers who are proficient in prescribing and monitoring gender-affirming hormones, a medically necessary intervention which falls within a nurse practitioner’s scope of practice.

Healthcare facilities and healthcare systems can improve the healthcare experiences and delivery of care for transgender adults by implementing this curricula content in continuing education programs offered to current health professionals, including clinicians and administrative and/or support staff members, as well as incorporating transgender health content during new employee orientation programs. Nurses working within these healthcare facilities and systems can become change champions to improve and facilitate the delivery of gender-affirming healthcare. These educational and health system changes may be particularly needed in rural facilities where choices of providers and healthcare facilitates are limited.

Research opportunities remain rich, plentiful, and needed to further contextualize the healthcare experiences of transgender adults, including the identification of facilitators and barriers to equitable gender-affirming care within all healthcare settings. Nurse scientists can help prioritize future research directions, aid in the development of interventions, and guide current and future public health initiatives and policies addressing the health of the transgender population.

Conclusion

Transgender adults experience unwelcoming healthcare environments, non-affirming healthcare professionals, and institutional practices that inhibit the delivery of gender-affirming care. Transgender individuals utilizing healthcare face widespread adversity and barriers to safe and equitable healthcare. The integration of gender-affirming approaches in healthcare is integral in supporting the health of transgender adults.

Statement of Significance.

What is known, or assumed to be true, about this topic:

Prior to the release of Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) in 2010, the discrimination against transgender adults in the US experience in healthcare was well studied. These individuals endure discrimination by healthcare professionals and within healthcare settings. Discriminatory experiences include inappropriate care, care refusal, and mistreatment by health providers. However, since the release of HP2020 in 2010 and the National Academy of Medicine’s call for more research addressing the disparities transgender adults experience in healthcare, little is known about the challenges transgender adults encounter within healthcare environments and the motivating factors and barriers met when attempting to access healthcare.

What this article adds.

By using an integrated mixed research literature review approach that was guided by the gender affirmation framework, we produced empirical findings representing the broadest possible understanding of the literature published post-HP2020. The 23 articles reviewed, which included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies, addressed numerous obstacles experienced by transgender adults accessing healthcare, discrimination from healthcare professionals and clinicians, restricted health insurance benefits for medically necessary care, and barriers to medically necessary care, such as cross-sex hormones, as well as primary and preventative healthcare. Further, our findings offer additional evidence that the gender affirmation framework can be used to better understand healthcare utilization and the health behaviors of transgender adults. The integration of gender-affirming approaches (affirming and acknowledging one’s gender identity/gender presentation) in healthcare is integral in supporting the health and well-being of transgender adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers F31NR017115 (Duke University School of Nursing) and T32NR016920 (University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing), as well as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Contributor Information

Ethan C. CICERO, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar, University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing.

Sari L. REISNER, Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health.

Susan G. SILVA, Duke University School of Nursing, Duke University School of Medicine.

Elizabeth I. MERWIN, Duke University School of Nursing, Rural Nurse Organization.

Janice C. HUMPHREYS, Duke University School of Nursing.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding National Academies Press; Washington, DC; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Ana M. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol 2015;70(9):832–864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Bhasin S, et al. Advancing methods for US transgender health research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016;23(2):198–207. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: Results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health 2012;102(1):118–122. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lombardi E, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, Malouf D. Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J Homosex 2001;42(1):89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisner SL, Hughto White J, Dunham EE, et al. Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Q 2015;93(3):484–515. 10.1111/1468-0009.12127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman JL. Gendered restrooms and minority stress: The public regulation of gender and its impact on transgender people’s lives. Journal of Public Management & Social Policy 2013;19(1):65 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legal Lambda. When health care isn’t caring: Lambda Legal’s survey of discrimination against LGBT people and people with HIV New York: Lambda Legal; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bockting W, Robinson B, Benner A, Scheltema K. Patient Satisfaction with Transgender Health Services. J Sex Marital Ther 2004;30(4):277–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bockting W, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health 2013;103(5):943–951. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keuroghlian AS, Reisner SL, White JM, Weiss RD. Substance use and treatment of substance use disorders in a community sample of transgender adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;152:139–146. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testa RJ, Sciacca LM, Wang F, et al. Effects of violence on transgender people. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2012;43(5):452 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman JL, Haas AP, Rodgers PL. Suicide attempts among transgender and gender non-conforming adults UCLA: The Williams Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reisner SL, Bradford J, Hopwood R, et al. Comprehensive transgender healthcare: The gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway Health. J Urban Health 2015;92(3):584–592. 10.1007/s11524-015-9947-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevelius J Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles 2013;68(11/12):675–689. 10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2016;72:S235–S242. 10.1097/qai.0000000000001088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crenshaw K Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev 1991:1241–1299

- 21.Fredrickson BL, Roberts TK. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q 1997;21(2):173–206 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol 2005;56:393–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Research in the schools : a nationally refereed journal sponsored by the Mid-South Educational Research Association and the University of Alabama 2006;13(1):29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrard J Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method 4th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Vol 4: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cicero EC, Black BP. “I was a spectacle…a freak show at the circus”: A transgender person’s ED experience and implications for nursing practice. J Emerg Nurs 2016;42(1):25–30. 10.1016/j.jen.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagen DB, Galupo MP. Trans individuals’ experiences of gendered language with health care providers: Recommendations for practitioners. Int J Transgend 2014;15(1):16–34 10.1080/15532739.2014.890560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med 2013;84:22–29 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roller CG, Sedlak C, Draucker CB. Navigating the system: How transgender individuals engage in health care services. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47(5):417–424 10.1111/jnu.12160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sevelius J, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, Johnson MO. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med 2014;47(1):5–16. 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shukla V, Asp A, Dwyer M, Georgescu C, Duggan J. Barriers to healthcare in the transgender community: A case report. LGBT Health 2014;1(3):229–232. 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson EC, Arayasirikul S, Johnson K. Access to HIV care and support services for African American transwomen living with HIV. Int J Transgend 2013;14(4):182–195. 10.1080/15532739.2014.890090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xavier JM, Bradford J, Hendricks M, et al. Transgender health care access in Virginia: A qualitative study. Int J Transgend 2012;14(1):3–17 10.1080/15532739.2013.689513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kattari SK, Walls NE, Speer SR. Differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing social services among transgender/gender nonconforming individuals by (dis)ability. Journal of social work in disability & rehabilitation 2017;16(2):116–140. 10.1080/1536710x.2017.1299661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz TM. Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: A consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Soc Sci Med 2014;110:65–73 69p. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shipherd JC, Mizock L, Maguen S, Green KE. Male-to-female transgender veterans and VA Health Care utilization. International Journal of Sexual Health 2012;24(1):78–87. 10.1080/19317611.2011.639440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffer M, Ayad J, Tungol JG, MacDonald R, Dickey N, Venters H. Improving transgender healthcare in the New York City correctional system. LGBT Health 2016. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am J Public Health 2013;103(10):1820–1829. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown GR. Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates’ correspondence: Implications for departments of correction. Journal of Correctional Health Care 2014;20(4):334–342. 10.1177/1078345814541533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Haan G, Santos GM, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF. Non-prescribed hormone use and barriers to care for transgender women in San Francisco. LGBT Health 2015;2(4):313–323. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radix AE, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE. Satisfaction and healthcare utilization of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in NYC: A community-based participatory study. LGBT Health 2014;1(4):302–308. 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nemoto T, Cruz TM, Iwamoto M, Sakata M. A tale of two cities: Access to care and services among african-american transgender women in Oakland and San Francisco. LGBT Health 2015;2(3):235–242. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitehead J, Shaver J, Stephenson R. Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilization among rural LGBT populations. PLoS One 2016;11(1):e0146139 10.1371/journal.pone.0146139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaffee KD, Shires DA, Stroumsa D. Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: Implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Med Care 2016;54(11):1010–1016. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kattari SK, Hasche L. Differences across age groups in transgender and gender non-conforming people’s experiences of health care discrimination, harassment, and victimization. J Aging Health 2015;28(2):285–306. 10.1177/0898264315590228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kattari SK, Walls NE, Whitfield DL, Langenderfer-Magruder L. Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. Int J Transgend 2015;16(2):68–79. 10.1080/15532739.2015.1064336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shires DA, Jaffee K. Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health & Social Work 2015;40(2):134–141 138p. doi:hsw/hlv025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White Hughto JM, Murchison GR, Clark K, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Geographic and individual differences in healthcare access for U.S. transgender adults: A multilevel analysis. LGBT Health 2016. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Feldman J, Brown GR, Deutsch MB, et al. Priorities for transgender medical and healthcare research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016;23(2):180–187. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]