Abstract

Objective:

Children with dependence on respiratory or feeding technologies are frequently admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU), but little is known about their characteristics or outcomes. We hypothesized that they are at increased risk of critical-illness-related morbidity and mortality compared to children without technology dependence.

Design:

Secondary analysis of prospective, probability-sampled cohort study of children from birth to 18 years of age. Demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed. Outcomes included death, survival with new morbidity, intact survival, and survival with functional status improvement.

Setting:

General and cardiovascular pediatric ICUs at seven participating children’s hospitals as part of the Trichotomous Outcome Prediction in Critical Care study.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Children with technology dependence composed 19.7% (1,989 of 10,078) of pediatric ICU admissions. Compared to those without these forms of technology dependence, these children were younger, received more ICU-specific therapeutics, and were more frequently readmitted to the ICU. Death occurred in 3.7% (n=74) of technology-dependent patients, and new morbidities developed in 4.5% (n=89). Technology-dependent children who developed new morbidities had higher Pediatric Risk of Mortality scores and received more ICU therapies than those who did not. A total of 3.0% (n=57) of technology-dependent survivors showed improved functional status at hospital discharge.

Conclusions:

Children with feeding and respiratory technology dependence composed approximately 20% of pediatric ICU admissions. Their new morbidity rates are similar to those without technology dependence, which contradicts our hypothesis that children with technology dependence would demonstrate worse outcomes. These comparable outcomes, however, were achieved with additional resources, including the use of more ICU therapies and longer lengths of stay. Improvement in functional status was seen in some technology-dependent survivors of critical illness.

Keywords: pediatrics, critical care, tracheostomy, gastrostomy, outcomes, morbidity

Introduction

Medically fragile children are frequently admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU). Children who are dependent on technology are an important group of medically fragile children, but the definition of technology dependence is not well established. Past research has predominantly focused on children with “complex chronic conditions,” a set of conditions defined by diagnostic coding that includes dependence on a medical device (1, 2). Feudtner et al. defined technology dependency as a situation in which “the failure or withdrawal of the technology would likely have adverse health consequences sufficient to require hospitalization” and included medication dependence as well as device dependence (3). An alternative definition of technology-dependent children includes only those who need a medical device to perform a necessary bodily function (4).

As a reflection of their underlying conditions, the inherent risks associated with their technology dependence, and their reduced physiologic reserve, these children may be at increased risk for critical illness, resulting in increased therapeutic needs, worsening dysfunction, and mortality. For example, chronic mechanical ventilation is associated with increased rates of medical resource utilization and longer hospital lengths of stay (5, 6). Little is known about the critical care course of technology-dependent children. While some technology-dependent children are routinely triaged to the pediatric ICU regardless of their reason for admission due to resource constraints on the general care wards, others are admitted with significant critical illness (7).

Since technology-dependent children represent a distinct group of patients in the pediatric ICU, their clinical courses and outcomes may differ from the general population. The aim of this study was to describe the demographic, physiologic, and therapeutic characteristics, as well as outcomes, of children dependent on respiratory and feeding technologies and compare them to children without such technology dependence during episodes of critical illness. Our definition of technology dependence—reliance on respiratory or gastrointestinal devices—identifies a representative, although not comprehensive, group of technology-dependent children. We hypothesized that children reliant on feeding or respiratory devices would be characterized by higher mortality and incur more new morbidity than the general pediatric ICU population.

Materials and Methods

Children from newborn to up to 18 years of age were probability sampled from general and cardiovascular pediatric intensive care units at seven participating children’s hospitals from December 4, 2011 to April 7, 2013 as part of the Trichotomous Outcome Prediction in Critical Care (TOPICC) study. Detailed methods for TOPICC have been previously described (8). Multiple other evaluations using this database have been published (9-12). As in the original TOPICC study, patients who were moribund at the time of admission were excluded, and only the first ICU admission during the study was eligible for inclusion. Pre-illness (“baseline”) functional status was assessed via the Functional Status Scale (FSS) on admission to the ICU using information from the caregiver and medical record as needed to establish functional status prior to the acute illness. FSS was additionally collected at the time of transfer from ICU to floor and at hospital discharge. The FSS is a relatively granular and objective classification method that characterizes functional status in a variety of domains (13, 14). Each of the six domains is scored from 1-5 points, with lower numbers indicating better function. Overall FSS scores have previously been categorized as good (6-7), mildly abnormal (8-9), moderately abnormal (10-15), severely abnormal (16-21), and very severely abnormal (>21) to reflect the patient’s dysfunction and to correlate with Pediatric Overall Performance Category scores (13). The decision to define a new morbidity as an increase in the overall FSS score of ≥3 points has been previously published (9). Similarly, we used a decrease of ≥3 points in the overall FSS score on hospital discharge to indicate significant improvement in functional status.

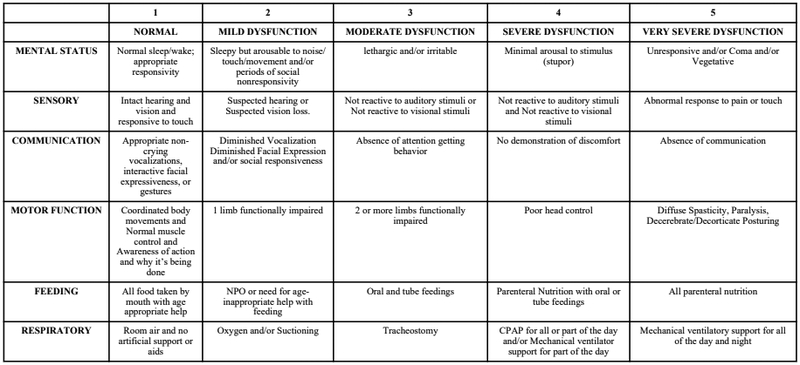

Patients dependent on feeding or respiratory technology were identified as those with a FSS of ≥3 in the feeding and/or respiratory domains (tube feedings and/or parenteral nutrition, and tracheostomy and/or chronic mechanical respiratory support, including continuous or bi-level positive airway pressure for part or all of the day, respectively) at baseline, as seen in Figure 1 (14). There may have been other children with device dependence present in the patient sample, but use of other devices was not collected in the TOPICC dataset. Therefore, this group served as a major, but not complete, sample of technology-dependent children. Feeding or respiratory technology-dependent patients were compared to patients without these technology dependencies. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all participating institutions.

Figure 1.

Functional Status Scale Scoring by Subdomains. Reprinted with permission from: Pollack M, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. The functional status scale (FSS): a new pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics. 2009; 124(1):e18-e28.

Descriptive data included age, gender, race, insurance status, admission characteristics, and primary system of dysfunction prompting admission. Resource use outcomes included length of stay, readmission to the ICU during the same hospitalization, and selected therapeutics (e.g., mechanical ventilation, vasoactive infusions, provision of antibiotics and steroids, and renal replacement therapy). Analyses were not adjusted to account for chronic therapeutics, including mechanical ventilation or parenteral nutrition, given our lack of information about the specifics of a patient’s baseline support. Severity of illness was measured with physiological profiles from Pediatric RIsk of Mortality 3 (PRISM) scoring (15). Outcomes included death, survival with new morbidity (total FSS increase of ≥3 points), intact survival (no significant change in functional status), and survival with functional status improvement (total FSS decrease of ≥3 points).

Counts and percentages are reported for categorical variables while medians and interquartile ranges are reported for continuous variables. Associations with baseline technology dependence were assessed with Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables (Tables 1 and 2). Although age was categorized for reporting, tests of association are based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test in order to utilize the ordered nature of the categories. For those assessments which included more parameters than could be assessed in a standard 2×2 table, a Monte Carlo approximation was used to estimate the p-value for Fisher’s exact test. The associations with development of new morbidity among technology-dependent survivors was analyzed analogously (Table 3). Summaries and analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC) under the direction of author RR.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Children With and Without Feeding and Respiratory Technology Dependence.

| Patient Characteristic | Technology Dependence (N=1989) |

No Technology Dependence (N=8089) |

P- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Pediatric ICU Admission in Years | <0.001 | ||

| < 1 | 470 (23.6%) | 2324 (28.7%) | |

| 1-5 | 767 (38.6%) | 2100 (26.0%) | |

| 5-12 | 473 (23.8%) | 1771 (21.9%) | |

| 12-18 | 279 (14.0%) | 1894 (23.4%) | |

| Gender | 0.053 | ||

| Female | 859 (43.2%) | 3689 (45.6%) | |

| Male | 1130 (56.8%) | 4400 (54.4%) | |

| Race | (1) | ||

| Black | 448 (22.5%) | 1848 (22.8%) | |

| White | 1066 (53.6%) | 4096 (50.6%) | |

| Unknown/Other | 475 (23.9%) | 2145 (26.5%) | |

| Primary Payer Type | <0.001 | ||

| Government | 1275 (64.1%) | 4145 (51.2%) | |

| Commercial | 660 (33.2%) | 3508 (43.4%) | |

| Unknown | 54 (2.7%) | 436 (5.4%) |

Significance for race was not analyzed due to the large number of unknown classifications.

Table 2.

Hospitalization Characteristics of Children With and Without Feeding or Respiratory Technology Dependence.

| Patient Characteristic | Technology Dependence (N=1989) |

No Technology Dependence (N=8089) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission PRISM Score (Median [IQR]) | 2.0 [0.0-5.0] | 2.0 [0.0-5.0] | 0.969 |

| Baseline FSS Score (Median [IQR]) | 12.0 [10.0-16.0] | 6.0 [6.0-6.0] | <0.001 |

| Admission Status | 0.585 | ||

| Elective | 713 (35.8%) | 2954 (36.5%) | |

| Emergent | 1276 (64.2%) | 5135 (63.5%) | |

| Admission Source | 0.070 | ||

| Emergency department | 688 (34.6%) | 2599 (32.1%) | |

| Inpatient unit | 869 (43.7%) | 3740 (46.2%) | |

| Direct admission from outside institution | 432 (21.7%) | 1750 (21.6%) | |

| System of Primary Dysfunction | <0.001 | ||

| Low risk diagnosesa | 145 (7.3%) | 799 (9.9%) | |

| Cardiac | 379 (19.1%) | 2051 (25.4%) | |

| Respiratory | 992 (49.9%) | 2384 (29.5%) | |

| Oncologic | 24 (1.2%) | 346 (4.3%) | |

| Neurologic | 225 (11.3%) | 1797 (22.2%) | |

| Other | 224 (11.3%) | 712 (8.8%) | |

| Pediatric ICU Therapies | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 1142 (57.4%) | 2697 (33.3%) | <0.001 |

| Vasoactive infusions | 408 (20.5%) | 1977 (24.4%) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic administration | 1559 (78.4%) | 5292 (65.4%) | <0.001 |

| Steroid administration | 713 (35.8%) | 2585 (32.0%) | 0.001 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 342 (17.2%) | 993 (12.3%) | <0.001 |

| Nitric oxide | 87 (4.4%) | 198 (2.4%) | <0.001 |

| High frequency ventilation | 35 (1.8%) | 71 (0.9%) | 0.001 |

| Intracranial pressure monitoring | 16 (0.8%) | 222 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Therapeutic hypothermia | 8 (0.4%) | 46 (0.6%) | 0.492 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 282 (14.2%) | 1089 (13.5%) | 0.401 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 41 (2.1%) | 112 (1.4%) | 0.031 |

| Extracorporeal support | 16 (0.8%) | 94 (1.2%) | 0.186 |

| Pediatric ICU Length of Stay in Days (Median [IQR]) | 3.0 [1.5-7.0] | 1.8 [1.0-4.1] | <0.001 |

| Pediatric ICU Readmission during Same Admission | 121 (6.1%) | 358 (4.4%) | 0.003 |

| Hospital Discharge Outcomes | <0.001 | ||

| Home or foster care | 1679 (84.4%) | 7448 (95.8%) | |

| Another acute care hospital | 63 (3.2%) | 111 (1.4%) | |

| Acute inpatient rehabilitation | 50 (2.5%) | 217 (2.7%) | |

| Chronic care or skilled nursing facility | 122 (6.1%) | 43 (0.5%) | |

| Death | 74 (3.7%) | 201 (2.5%) | |

| Hospital Discharge FSS Score (Median [IQR])b | 12.0 [10.0-16.0] | 6.0 [6.0-7.0] | <0.001 |

PRISM – Pediatric RIsk of Mortality 3 Score; FSS – Functional Status Scale; ICU – intensive care unit; IQR – interquartile range

Low risk diagnoses included diabetic ketoacidosis, and hematologic, musculoskeletal, and renal dysfunction.

Discharge FSS score was analyzed only for survivors.

Table 3.

Comparison of Survivors with Feeding or Respiratory Technology-Dependence With and Without New Morbidities

| Patient Characteristic | New Morbidity (n=89) |

No New Morbidity (n=1826) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission PRISM Score (Median [IQR]) | 3.0 [0.0-8.0] | 2.0 [0.0-5.0] | 0.006 |

| Baseline FSS Score (Median [IQR]) | 13.0 [9.0-16.0] | 12.0 [10.0-16.0] | 0.993 |

| Admission Status | <0.001 | ||

| Elective | 16 (18.0%) | 681 (37.3%) | |

| Emergent | 73 (82.0%) | 1145 (62.7%) | |

| Admission Source | <0.001 | ||

| Emergency department | 24 (27.0%) | 644 (35.3%) | |

| Inpatient unit | 29 (32.6%) | 804 (44.0%) | |

| Direct admission from outside institution | 36 (40.4%) | 378 (20.7%) | |

| System of Primary Dysfunction | 0.020 | ||

| Low risk diagnosesa | 2 (2.2%) | 141 (7.7%) | |

| Cardiac | 12 (13.5%) | 343 (18.8%) | |

| Respiratory | 59 (66.3%) | 897 (49.1%) | |

| Oncologic | 2 (2.2%) | 21 (1.2%) | |

| Neurologic | 7 (7.9%) | 213 (11.7%) | |

| Other | 7 (7.9%) | 211 (11.6%) | |

| Pediatric ICU Therapies | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 70 (78.7%) | 1011 (55.4%) | <0.001 |

| Vasoactive infusions | 29 (32.6%) | 329 (18.0%) | 0.001 |

| Antibiotic administration | 77 (86.5%) | 1416 (77.5%) | 0.049 |

| Steroid administration | 44 (49.4%) | 627 (34.3%) | 0.004 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 26 (29.2%) | 281 (15.4%) | 0.002 |

| Nitric oxide | 8 (9.0%) | 60 (3.3%) | 0.012 |

| High frequency ventilation | 5 (5.6%) | 24 (1.3%) | 0.009 |

| Intracranial pressure monitoring | 2 (2.2%) | 11 (0.6%) | 0.120 |

| Therapeutic hypothermia | 2 (2.2%) | 4 (0.2%) | 0.028 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 36 (40.4%) | 212 (11.6%) | <0.001 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 6 (6.7%) | 22 (1.2%) | 0.001 |

| Extracorporeal support | 3 (3.4%) | 8 (0.4%) | 0.012 |

| Pediatric ICU Length of Stay in Days (Median [IQR]) | 10.0 [3.0-31.7] | 2.9 [1.4-6.6] | <0.001 |

| Pediatric ICU Readmission | 20 (22.5%) | 87 (4.8%) | <0.001 |

| Discharge Location | <0.001 | ||

| Home or foster care | 56 (62.9%) | 1623 (88.9%) | |

| Another acute care hospital | 10 (11.2%) | 53 (2.9%) | |

| Acute inpatient rehabilitation | 5 (5.6%) | 45 (2.5%) | |

| Chronic care or skilled nursing facility | 18 (20.2%) | 104 (5.7%) | |

| Hospital Discharge FSS Score (Median [IQR]) | 17.0 [14.0-21.0] | 12.0 [9.0-16.0] | <0.001 |

PRISM – Pediatric RIsk of Mortality 3 Score; FSS – Functional Status Scale; ICU – intensive care unit; IQR – interquartile range

Low risk diagnoses included diabetic ketoacidosis, and hematologic, musculoskeletal, and renal dysfunction.

Results

Among 10,078 total admissions over approximately 16 months, 1,989 (19.7%) were technology-dependent at baseline. Overall, children with feeding and respiratory technology dependence were younger (p<0.001) and had a higher incidence of government insurance (p<0.001) than those without technology dependence (Table 1).

The clinical characteristics of children with and without technology dependence are reported in Table 2. As expected, the baseline FSS scores of technology-dependent children were higher than for those without dependence (p<0.001). Both groups had predominantly emergent admissions, were frequently admitted from an inpatient unit, and had similar severity of illness scores. The system of primary dysfunction prompting admission was predominantly respiratory for both groups. Compared to children without technology dependence, those with technology dependence stayed in the pediatric ICU longer (median duration, 7.1 days vs. 4.6 days, p<0.001). The hospital discharge FSS scores were similar to the baseline scores for both groups. While pre-hospital origin is not known, discharge outcomes differed between the groups with outcomes of mortality and discharge to chronic care or skilled nursing care facilities and other acute care facilities being more common among technology-dependent patients than those without technology dependence (p<0.001). Discharge to acute inpatient rehabilitation was similar between groups.

Use of critical care therapeutics (Table 2) differed between the two groups of patients. Technology-dependent patients were more likely to receive mechanical ventilation (p<0.001), antibiotics (p<0.001), steroids (p<0.001), total parenteral nutrition (p<0.001), inhaled nitric oxide (p<0.001), high frequency ventilation (p=0.001), and renal replacement therapy (p=0.031). They were less likely to receive vasoactive medications (p<0.001) and were less likely to have intracranial pressure monitoring (p<0.001). They were readmitted to the pediatric ICU during that same hospitalization at a significantly higher rate than children without technology dependence (6.1% vs. 4.4%, p=0.003).

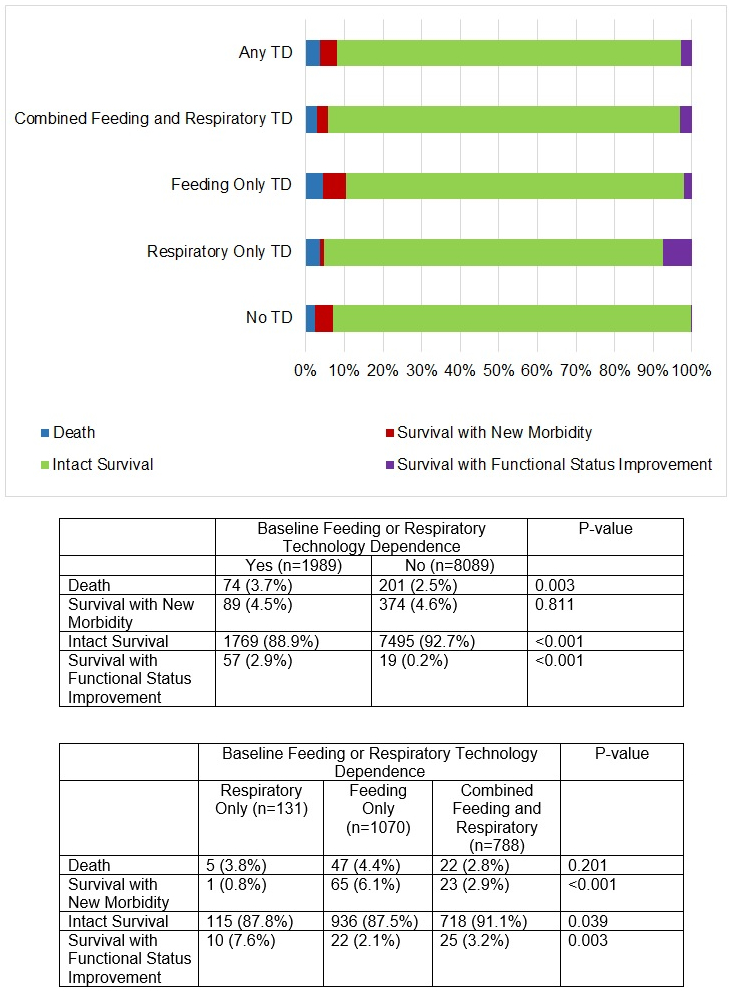

The distribution of mortality and new morbidity for children with and without various types of feeding and respiratory technology dependence is shown in Figure 2. Technology-dependent children died more frequently than did those without dependence (3.7% vs 2.5%, p=0.003), while new morbidities developed in similar percentages of both groups (4.5% vs. 4.6%). Within the technology-dependent group, both mortality and new morbidity were highest in the subgroup of patients with only feeding technology-dependence (4.4% and 6.1%, respectively). Improvement in functional status during the hospitalization was observed in 57 (3.0%) technology-dependent survivors, while only 19 (0.2%) survivors without technology dependence demonstrated survival with improvement (p <0.001).

Figure 2.

Outcomes of Children With and Without Feeding and Respiratory Technology Dependence.

TD – technology dependence

The clinical characteristics of the 89 (4.6%) technology-dependent survivors who developed new morbidities compared to the 1,826 who did not are shown in Table 3. Children with feeding and respiratory technology dependence who developed new morbidities had similar baseline FSS scores to those who did not. However, they had higher PRISM scores on admission (p=0.006) and were more likely to be admitted on an emergency basis (p <0.001) or from an outside facility (p<.001). Children with technology dependence who developed new morbidities differed from those who did not develop new morbidities with regard to primary systems of dysfunction, with higher rates of respiratory dysfunction and lower rates of neurologic dysfunction (p=0.02).

Children with baseline feeding and respiratory technology dependence were most likely to have worsening in their respiratory (n=53, [59.6%]) and motor (n=30 [33.7%]) FSS domains. Pediatric ICU length of stay was markedly longer in technology-dependent children who developed new morbidities (p<0.001), and they utilized significantly more high-intensity ICU therapies including mechanical ventilation (p<0.001), vasoactive infusions (p=0.001), neuromuscular blockade (p<0.001), and extracorporeal support (0.012). Those who developed new morbidities were re-admitted to the pediatric ICU at nearly five times the rate as those who did not (p<0.001). Those with new morbidities were more likely to be transferred to another hospital or discharged to rehabilitation and chronic care facilities than those without new morbidities (p<0.001).

Discussion

Children with respiratory and feeding technology dependence composed approximately 20% of pediatric ICU admissions, which is fewer than in prior studies focusing on the broader definitions of medically fragile or complex children (16, 17). Some of this difference may be in the methodology and focus of the studies, as this study is the first to define technology dependence using the FSS. Our definition, which uses only the respiratory and feeding domains in the FSS, is more narrowly tailored than many other definitions of medical complexity, and it will not include some children with device dependence, such as those with ventriculoperitoneal shunts, or those who receive dialysis or subcutaneous pulmonary hypertension medications.

Compared to those without feeding or respiratory technology dependence, technology-dependent children admitted to the pediatric ICU were younger, were more frequently insured by governmental health insurance, and most importantly, received more ICU-specific therapeutics and were more frequently readmitted to the critical care service following care on the general ward. Children dependent on feeding or respiratory technology had higher mortality rates than children without technology dependence. While morbidity rates were similar between the two groups, technology-dependent children required longer lengths of stay. Both mortality and morbidity were highest in the subgroup of patients with only feeding technology dependence. Improvement in functional status during the hospitalization was noted in 3.0% of technology-dependent survivors. These functional status improvements presumably occurred because these patients were admitted for a procedure, such as tracheostomy decannulation, which improved their FSS classification or a corrective procedure which improved their underlying physiologic reserve. We did not assess how different baseline degrees of dysfunction among technology-dependent children were related to outcomes because our aim was to provide a global description of critically ill technology-dependent children.

Overall, children dependent on respiratory or feeding technology had a similar pattern of primary admission reasons and illness severity as children without dependence on these technologies. Their resource use, however, was greater than that of patients without technology dependence, particularly as measured by ICU length of stay and need for discharge to a location other than home. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating higher medical resource utilization in children with complex medical conditions (4, 16, 18). Prior studies additionally demonstrated that children dependent on long-term mechanical ventilation have prolonged hospital lengths of stay, mortality, and discharges to long-term care facilities than other children with complex conditions (5), findings which are mirrored in our population of ICU patients. These disparities suggest that there may be important barriers to discharge in technology-dependent patients, including care requirements after hospital discharge. But because the TOPICC dataset was collected for other purposes, it did not collect data regarding specific issues in the care of technology-dependent children that may be important to questions raised in this study. Specifically, a patient’s primary residence was not noted, so the proportion of children discharged to a location other than home may not represent a change from baseline.

As medical care is increasingly able to support children through potentially life-ending conditions, the proportion of patients who are dependent on technology is growing (19, 20). Simultaneously, the focus of critical care has evolved from saving lives to preserving function. General pediatric ICU mortality rates are approximately 2.5-5.0%, while new morbidity rates are approximately twice as high (8, 9). It has been suggested that a portion of the improving mortality rate over time has been in exchange for a higher morbidity rate (21). Therefore, the provision of intensive care is changing the population of our ICUs, leading to the significant representation of technology-dependent patients in today’s pediatric ICUs. ICU populations routinely evolve as medical care changes and improves. For example, when neonatal care improved the survival of premature infants, the impact on pediatric ICUs was notable (22). Additionally, increasing numbers of cardiac intensive care units now provide subspecialized care for children with congenital and acquired heart disease (23).

Prior studies of children following critical illness demonstrate an unclear trajectory of functional status (9, 24, 25, 26). Children across a range of ages, diagnostic categories, and surgical statuses acquire new morbidities with critical illness (9, 23, 27). Many children with medical complexity return to their baseline level of function following an episode of critical illness (28). Typpo et al. determined that the vast majority of children with chronic disease returned to their functional baseline by discharge from the ICU, but their assessment of baseline and discharge outcomes was limited to the Pediatric Performance Categories, subjective assessments that do not specifically identify technology dependence (25). A recent 3-year follow-up study also using the FSS observed that new morbidities continued to accrue in many critically ill children even after hospital discharge, regardless of pre-illness functional status, and children infrequently exhibited improvement in functional status (26). Because our study does not investigate these longer term outcomes, similar outcomes at the time of hospital discharge does not preclude disparate long-term changes in functional status between children with and without technology dependence.

Conclusion

Children dependent on feeding and respiratory technology as defined by the FSS compose a significant proportion of pediatric ICU admissions. While they had a higher mortality rate, their new morbidity rates were similar to those without technology dependence, and they had similar risk factors for these outcomes as children without technology dependence. These patterns contradict our hypothesis (and challenge the conventional wisdom) that children with technology dependence would demonstrate an additional burden of new morbidities from critical illness as compared to children without baseline physiologic dysfunction. However, these comparable outcomes were achieved only with a greater expenditure of resources, including the use of more ICU therapies and longer lengths of stay. Outcomes following critical illness are related to the patient’s admission physiologic instability and the need for ICU therapeutics. Notably, approximately 3% of technology-dependent patients significantly improved their functional status during pediatric ICU admission.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Supported, in part, by the following cooperative agreements from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD049983, U10HD050012, U10HD063108, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, and U01HD049934. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Heneghan, Reeder, Dean, Meert, Berg, Carcillo, Tamburro, and Pollack received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Heneghan disclosed that the authors are supported, in part, by the following cooperative agreements from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH, Department of Health and Human Services: U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD049983, U10HD050012, U10HD063108, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, and U01HD049934. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. Drs. Reeder, Dean, Meert, and Berg’s institutions received funding from the NIH. Drs. Carcillo and Pollack’s institutions received funding from the NICHD. Dr. Newth received funding from Philips Research North America. Dr. Dalton received funding from Innovative ECMO Concepts. Dr. Tamburro’s institution received funding from the US FDA Office of Orphan Product Development and ONY, Inc; he received funding from Springer-Verlag Publishing; and he disclosed government work. Dr. Pollack received Philanthropic support from Mallinckrrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Individuals Acknowledged and Roles

Teresa Liu, MPH, CCRP; University of Utah (project management, Data Coordinating Center)

Jean Reardon, MA, BSN, RN; Children’s National Medical Center (institutional project management, data collection)

Elyse Tomanio, BSN, RN; Children’s National Medical Center (institutional project management, data collection)

Morella Menicucci, MD, CCRP; Children’s National Medical Center (data collection)

Fidel Ramos, BA; Children’s National Medical Center (institutional project management, data collection)

Aimee Labell, MS, RN; Phoenix Children’s Hospital (institutional project management, data collection)

Courtney Bliss, BS, DTR; Phoenix Children’s Hospital (data collection)

Jeffrey Terry, MBA; Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (data collection)

Margaret Villa, RN; Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA (institutional project management, data collection)

Jeni Kwok, JD; Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Mattel Children’s Hospital (institutional project management, data collection)

Amy Yamakawa, BS; Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA (data collection)

Ann Pawluszka, BSN, RN; Children’s Hospital of Michigan (institutional project management)

Symone Coleman, BS, MPH; Children’s Hospital of Michigan (data collection)

Melanie Lulic, BS; Children’s Hospital of Michigan (data collection)

Mary Ann DiLiberto, BS, RN, CCRC; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (institutional project management, data collection)

Carolann Twelves, BSN, RN; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (data collection)

Monica S. Weber, RN, BSN, CCRP; University of Michigan (institutional project management, data collection)

Lauren Conlin, BSN, RN, CCRP; University of Michigan (data collection)

Alan C. Abraham, BA, CCRC; Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (institutional project management, data collection)

Jennifer Jones, RN; Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (data collection)

Jeri Burr, MS, RN-BC, CCRC; University of Utah (project management, Data Coordinating Center)

Nichol Nunn, BS, MBA; University of Utah (project management, Data Coordinating Center)

Alecia Peterson, BS, CMC; University of Utah (project management, Data Coordinating Center)

Carol Nicholson, MD (former Project Officer, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, for part of the study period)

References

- 1.Ralston SL, Harrison W, Wasserman J, et al. Hospital variation in health care utilization by children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(5):860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014; 133 (6):e1647–e1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feudner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, et al. Technology-dependence among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort review. BMC Pediatrics. 2005; 5(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dosa N, Boeing N, Kanter R. Excess risk of severe acute Illness in children with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 2001; 107(3):499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benneyworth BD, Gebremariam A, Clark SJ, et al. Inpatient health care utilization for children dependent on long-term mechanical ventilation. Pediatrics. 2011; 127(6): e1533–e1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JG, Graham RJ, Roberson DW, et al. Patient characteristics associated with in-hospital mortality in children following tracheotomy. Arch Dis Child. 2010; 95(9):703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russ CM, Agus M. Triage of intermediate-care patients in pediatric hospitals. Hosp Pediatr 2015; 5(10):542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Simultaneous prediction of new morbidity, mortality, and survival without new morbidity from pediatric intensive care: a new paradigm for outcomes assessment. Crit Care Med 2015; 43(8):1699–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. Pediatric intensive care outcomes: development of new morbidities during pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15(9):821–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keele L, Meert K, Berg RA, et al. Limiting and withdrawing life support in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17(2):110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meert K, Keele L, Morrison W, et al. End-of-life practices among tertiary care pediatric intensive care units in the US: a multicenter study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015; 16(7):e231–e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinter MS, Holubkov R, Steurer MA, et al. Pediatric hematopoietic cell transplant patients who survive critical illness frequently have significant but recoverable decline in functional status. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018; 24(2):330–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack M, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. The relationship between the functional status scale and the pediatric overall and cerebral performance categories. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168(7):671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack M, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. The functional status scale (FSS): a new pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics. 2009; 124(1):e18–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack M, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. The pediatric risk of mortality score: update 2015. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17(1):2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan T, Rodean J, Richardson T, et al. Pediatric critical care resource use by children with medical complexity. J Pediatr 2016; 177:197–203.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Chronic conditions among children admitted to US pediatric intensive care units: their prevalence and impact on risk for mortality and prolonged length of stay. Crit Care Med 2012; 40(7):2916–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus KL, Henderson CM, Boss RD. Chronic critical illness in infants and children: a speculative synthesis on adapting ICU care to meet the needs of long-stay patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17(8):743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010; 126(4):647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, et al. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010; 126(4):638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dominguez T Are we exchanging morbidity for mortality in pediatric intensive care? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15(9):898–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slonim AD, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE, et al. The impact of prematurity: a perspective of pediatric intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2000; 28(3):848–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burstein DS, Jacobs JP, Li JS, et al. Care Models and Associated Outcomes in Congenital Heart Surgery. Pediatrics. 2011; 127(6):e1482–e1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bone M, Feinglass J, Goodman D. Risk factors for acquiring functional and cognitive disabilities during admission to a PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15(7):640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Typpo K, Petersen NJ, Petersen LA, et al. Children with chronic illness return to their baseline functional status after organ dysfunction on the first day of admission in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr 2010; 167(1):108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinto NP, Rhinesmith EW, Kim TY, et al. Long-term function after pediatric critical illness: results from the survivor outcomes survey. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017; 18(3):e122–e130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiser DH, Tilford JM, Roberson PK. Relationship of illness severity and length of stay to functional outcomes in the pediatric intensive care unit: a multi-institutional study. Crit Care Med 2000; 28(4): 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]