Abstract

Background:

Personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions have been repeatedly found to reduce drinking among undergraduates. However, effects tend to be small, potentially due to inattention to and inadequate processing of the information. Adding a writing component to PNF interventions may allow for greater cognitive processing of the feedback, thereby boosting intervention efficacy. Additionally, expressive writing (EW) has been shown to reduce drinking intentions; however, studies have not examined whether it can reduce drinking behavior. The present experiment evaluated whether including a writing task would improve the efficacy of PNF and whether EW alone can be used to reduce drinking and alcohol-related problems.

Method:

Heavy drinking undergraduates (N=250) were randomized to receive either: 1) PNF about their alcohol use; 2) EW about a negative, heavy drinking occasion; 3) PNF plus writing about the norms feedback; or 4) attention control feedback about their technology use in an online brief intervention. Participants (N=169) then completed a one-month follow-up survey about their past month alcohol use and alcohol-related problems online.

Results:

PNF plus writing reduced alcohol-related problems compared to all other conditions. No significant reductions were found for EW. Both PNF and PNF plus writing reduced perceived norms and perceived norms mediated intervention effects for both feedback conditions.

Conclusions:

The current findings suggest that adding a writing component to traditional norms-based feedback approaches might be an efficacious strategy, particularly for reducing alcohol-related consequences.

Keywords: alcohol use, brief intervention, narrative, social norms, cognitive processing

Risky drinking patterns are relatively common among college students, with 32% of students reporting at least one heavy drinking episode (consuming 5+ drinks on an occasion) in the past two weeks (Johnston et al., 2016). Heavy drinking occasions are associated with a variety of negative consequences such as physical and sexual assaults (Abbey, 2011; Abbey et al., 1998; Hingson, 2010; Hingson et al., 2009), car accidents (Hingson, 2010; Hingson et al., 2009), missed class and poor academic performance (Presley, 1993; Wechsler et al., 1998), blackouts (Read et al., 2006; White, 2003; White & Hingson, 2013), major depression (Rosenthal et al., 2018), and other consequences (Read et al., 2006). The prevention and/or reduction of these alcohol-related consequences in addition to the reduction of alcohol consumption is incredibly important. The current study aims to improve upon an existing empirically-supported intervention strategy in an attempt to reduce college students’ experiences of alcohol-related consequences.

Personalized Normative Feedback Interventions

Reviews and meta-analyses of alcohol intervention research have often indicated that normative feedback interventions are successful at reducing drinking among college samples, especially on a short-term basis (e.g., Cadigan et al., 2015; Carey et al., 2009; Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Dotson et al., 2015 ; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006; Riper et al., 2009; Walters & Neighbors, 2005), although findings have not been consistent across all studies (e.g., see Huh et al., 2015). Personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions work by correcting misperceptions of drinking norms using a two-part discrepancy. Feedback includes: (1) the amount of alcohol they reported drinking compared to actual rates of drinking for the typical student; and (2) their estimates of typical student drinking compared to actual drinking behavior for the typical student. Upon learning that their drinking behavior is not normative, individuals may experience cognitive dissonance, which can prompt behavior change to more closely match the norm (Berkowitz, 2004; Festinger, 1962). Norms-based interventions utilize this dissonance by informing individuals that the actual norm is lower than their perceived norms, which leads to reductions in drinking. College students are an excellent target for norms-based alcohol interventions because drinking is a common behavior among undergraduates (Johnston et al., 2014) and students overestimate how often and how much other students drink (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Campo et al., 2003; Garnett et al., 2015; McAlaney & McMahon, 2007; Perkins & Wechsler, 1996). After receiving the feedback, participants’ perceived norms and actual drinking behaviors have been shown to decrease significantly at follow-ups (e.g., LaBrie et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2007; Lojewski et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2016).

Expressive Writing and Alcohol Use

Few studies have specifically examined whether expressive writing (EW) can result in reduced drinking intentions and drinking behavior. The first study to document that EW can decrease alcohol use (Spera et al., 1994) asked participants who had recently lost their jobs to either write about their deepest thoughts and feelings regarding their recent termination (experimental condition) or their plans for the day/plans for the job search (control writing condition). A third group served as a non-writing control group to compare to writing conditions to test whether there was an effect of writing. Although reducing alcohol use was not an aim of this study, the researchers found that participants in the experimental writing condition reported drinking significantly less alcohol at six-week follow-up compared to participants in the control conditions. This study is the first to report reduced alcohol consumption in an EW paradigm and provides preliminary support that such a paradigm could be adapted and used as a brief alcohol intervention.

The first study to specifically evaluate EW as an alcohol intervention asked 200 college students to write once about: 1) a heavy drinking occasion that was negative; 2) a heavy drinking occasion that was positive; or 3) their first day of college (Young et al., 2013). After completing the writing task, participants were asked to report their intentions for drinking over the coming month. Results indicated that participants in the negative alcohol event condition intended to drink significantly fewer drinks per week and engage in marginally fewer heavy drinking occasions compared to control (Young et al., 2013). Further analyses examined whether condition effects were moderated by typical drinking (a composite of drinks per week, drinking frequency, and average drinks consumed on a typical occasion) and by AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; Babor et al., 2001) scores, a measure of hazardous or harmful drinking. Lighter drinkers (i.e. individuals who drank less than the average for typical drinking in the sample) reported marginally lower intended typical drinks per occasion in the positive condition compared to control, and heavier drinkers (i.e. individuals who drank more than the average for typical drinking in the sample) reported increased intended typical drinks per occasion and increased frequency of drinking intentions in the positive condition compared to control. Writing about a negative drinking event was associated with marginally lower drinking frequency intentions for lighter drinkers and marginally higher drinking frequency intentions for heavier drinkers. Additionally, writing about a negative drinking occasion was associated with lower intentions to engage in heavy drinking episodes among more hazardous drinkers (i.e., individuals who scored higher than the mean of the sample on the AUDIT) and did not differ from control among less hazardous drinkers (i.e., individuals who scored lower than the mean of the sample on the AUDIT). Findings provide preliminary evidence that an EW paradigm could be adapted as a brief alcohol intervention to reduce drinking intentions.

A second study examined shame and guilt as mechanisms through which a narrative intervention might increase readiness to change one’s drinking and decrease intentions to drink in the future (Rodriguez et al., 2015). Four hundred ninety-five participants completed the narrative intervention using the same prompts as the Young et al. (2013) study. Condition effects were found such that writing about a negative drinking event was associated with reductions in intended drinks per week, peak drinks, and drinks per occasion compared to the control condition. Participants in the negative drinking event condition reported higher levels of event-related guilt and shame compared to control and no such difference was found between the positive writing condition and control. Additionally, guilt related to the drinking event, but not shame, was found to mediate intervention effects on readiness to change, which mediated the association between guilt–reparative behavior and future drinking intentions.

While the EW paradigm has been implemented for decades (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986), adapting this paradigm specifically to reduce drinking is new and largely unexplored. The present research will examine the efficacy of EW as a standalone intervention to reduce drinking behavior. Additionally, the present study will evaluate whether adding a writing component to a PNF intervention will improve intervention efficacy by increasing attention to and cognitive processing of the feedback, as a lack of attention and cognitive processing are currently limitations of online, remotely-delivered PNF interventions.

Limitations of the PNF Approach

Although PNF has been shown to effectively reduce drinking, this approach does have limitations. There are currently mixed findings in the literature regarding the efficacy of in-person versus remotely-delivered PNF interventions. While some studies have shown similar results across in-person and remotely-delivered PNF for short-term follow-ups (Butler & Correia, 2009; Doumas & Hannah, 2008; White et al., 2007), other work has found that in-person PNF interventions tend to be more effective than web-based PNF interventions (Carey et al., 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2015), particularly when combined with MI and for long-term follow-ups (Walters et al., 2009; White et al., 2007). Theories related to depth of processing such as the levels of processing effect (Craik & Lockhart, 1972), the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), and the heuristic-systematic model (Chaiken et al., 1989) all suggest that this potential difference in intervention efficacy might be due to the amount of cognitive processing and attention given to the feedback, which is likely to be higher among in-lab participants. Therefore participants who receive PNF interventions remotely may not be cognitively processing the material fully, which may result in maintaining current normative misperceptions of alcohol use and continuing to engage in hazardous drinking. This inattention and potential lack of understanding or retention of the information and how it is relevant to one’s own drinking may explain why effect sizes for remote interventions tend to be smaller than in-person interventions (Carey et al., 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2015).

A recent study addressed this concern by assessing attentiveness related to a remote PNF intervention. Specifically, the authors examined participants’ attentiveness to the normative information and evaluated whether participants were alone or with others and whether they were engaged in other activities when they viewed the feedback (Lewis & Neighbors, 2015). Results indicated that, overall, participants reported attending to the feedback and most participants viewed their feedback alone (74.5%). However, nearly two-thirds (62.3%) of participants reported doing at least one other thing while viewing their feedback and 30.1% reported doing two or more activities while viewing their feedback (e.g., commuting, eating, etc.; Lewis & Neighbors, 2015). Multi-tasking while viewing the feedback was associated with more risky health behaviors at baseline and follow-up. The intervention was more effective at reducing drinks consumed per week at three-month follow-up for individuals who were more attentive to the feedback (Lewis & Neighbors, 2015).

Thus it appears that although participants were somewhat attentive to the feedback, and better outcomes were achieved for individuals who were more engaged with the feedback, there is room for improvement in terms of processing the normative information. Another study examined processing of the intervention information as a potential area for improvement by testing whether rereading and/or recalling the information from the feedback would be more effective at reducing drinking at follow-up (Jouriles et al., 2010). In this study, all participants received personalized feedback about their drinking and were then either: a) sent home (typical feedback condition); b) asked to reread the feedback for 20 minutes; or c) asked to write down as much as they could recall about the feedback. Participants in both the reading and recall conditions remembered more detail regarding the feedback and reported greater reductions in drinking at follow-up relative to the typical feedback condition (Jouriles et al., 2010). In a similar fashion, adding a writing component to an existing PNF intervention that is delivered remotely could increase processing of the material as participants would be asked to express their thoughts and feelings regarding the feedback which might more closely approximate the information processing that occurs in a face-to-face intervention. This task might further boost the effectiveness of PNF as participants engage more fully with the material and perhaps better understand norms and how they can influence one’s behavior.

Current Study Aims

The current study evaluates the efficacy of adding a writing component to a traditional PNF intervention and evaluates EW as a standalone alcohol intervention to reduce drinking and alcohol-related problems among college drinkers. The additional cognitive processing required by writing-based interventions may contribute to a better understanding of social influences on one’s behavior and may compel participants to thoughtfully consider their drinking, which may ultimately provide participants with an opportunity to formulate a plan to change their current drinking behavior. We expected that an EW intervention would lead to reduced drinking and problems at follow-up compared to control. We also hypothesized that a personalized normative feedback plus writing intervention would be more effective at reducing drinking and alcohol-related problems at one-month follow-up when compared to control and when compared to all other conditions. Furthermore, we hypothesized that intervention effects for the PNF and PNFplus conditions, but not for EW, would be mediated by perceived norms. The results of this investigation may suggest that adding a narrative component can boost the efficacy of existing intervention approaches.

Materials and Methods

Participants

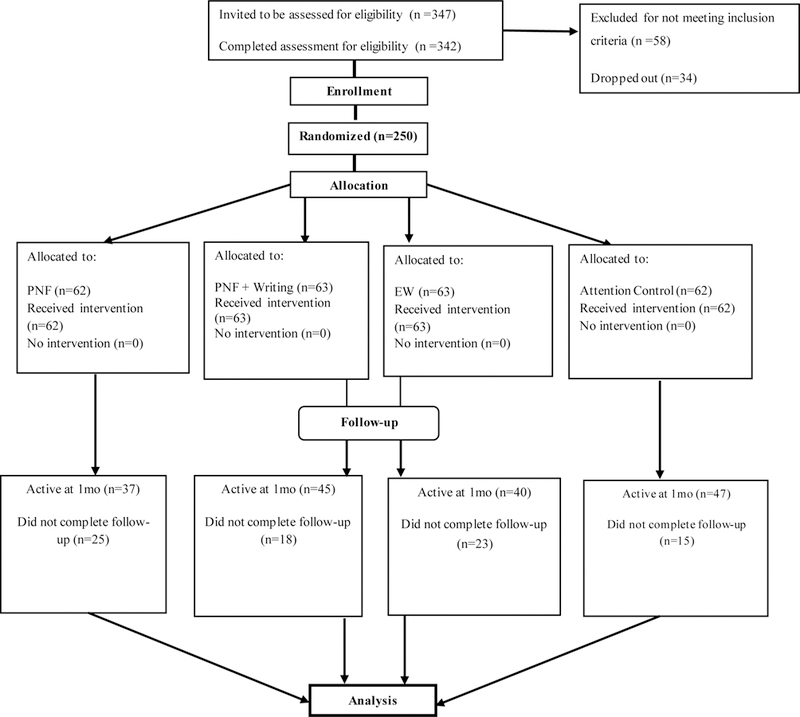

Participants included 250 undergraduates students (70.4% female) between 18 and 26 years old (M = 21.02, SD = 2.16) who provided consent to participate in the study, reported drinking at least four drinks in one sitting for women and five drinks in one sitting for men in the last month, completed the baseline assessment and intervention, and answered at least two out of three check questions correctly. This study took place at a large, public university in the south with mostly commuter students. Participants were diverse in terms of race and ethnicity, with 44.5% White/Caucasian, 1.6% Native American/American Indian, 12.1% Black/African American, 22.7% Asian, 1.2% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 4.9% Multi-ethnic, and 13.0% Other. Additionally, 30.8% of the sample identified as Hispanic/Latino. Individuals were recruited to participate through in-class presentations, flyers posted around campus, and the through the university’s online research system. Participants who completed baseline received extra course credit and participants who completed follow-up received $25 Amazon gift card codes. All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participant flow throughout the study can been seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Procedures

Individuals first answered two screening questions in an online survey to confirm that they met screening criteria for the study regarding their age and alcohol use. After meeting criteria, participants were directed to an online survey where they responded to questions regarding their demographics, alcohol use, drinking norms, and experience of alcohol-related problems. Then participants were randomized to one of four conditions. In these conditions, participants received either: 1) PNF about alcohol use; 2) EW about a negative, heavy drinking occasion; 3) PNF plus writing about the norms feedback; or 4) attention control feedback about technology use. To examine whether the intervention reduced future drinking and alcohol-related consequences, a one-month follow-up questionnaire was emailed to participants to be completed online.

Intervention Procedure

Personalized Normative Feedback.

Participants in the PNF conditions received personalized information comparing their self-reported typical number of drinking days per week (from their responses to the Quantity/Frequency Scale), average number of drinks per occasion (from their responses to the Quantity/Frequency Scale), and typical number of drinks per week (from their responses to the Daily Drinking Questionnaire) to the drinking of typical same-sex students at their university. The feedback piece including the actual drinking behaviors of same-sex students from their university came from a drinking norms documentation study of 1052 randomly selected students from the university that took place in 2012 as part of a larger grant funded project using PNF (R01AA014576). We chose to use norms from the previous norms documentation survey because it provided a much larger, more diverse sample that is more representative of the campus community as a whole compared to the baseline survey from this study, and thus more accurately depicts typical drinking for males and females on campus. This personalized normative feedback information was presented both in words and in graphs.

Control Feedback.

Participants in the control condition received personalized information in text and graph form comparing their self-reported time spent texting, playing video games, and downloading music (from their responses to the Attention Control Questionnaire) to both their norms for those behaviors (also from their responses to the Attention Control Questionnaire) and the actual behaviors of typical same-sex students from their university. The numbers for the average time same-sex university students spend actual texting, playing video games, and downloading music were also derived from the norms documentation study mentioned above.

PNF Plus Writing.

After receiving personalized feedback about their drinking identical to the feedback in the PNF condition, participants in the PNF plus writing condition were asked to write for 15–20 minutes about their reactions to the feedback. They detailed how they felt about their drinking behavior after viewing the feedback and any plans they may have to change their drinking behavior. The writing prompt reads, “Please think back to the personalized feedback that you just received. How do you compare to others based on your drinking? Does this fit with your expectations of how your drinking compares to others’ drinking? How does that comparison make you feel? What does that make you think about your drinking behavior? All of the information you tell us will remain confidential and will not be shared with anyone outside of the research study. Don’t worry about spelling, sentence structure, or grammar. The only rule is that once you begin writing, continue to do so for 20 minutes until your time is up”.

Expressive Writing Prompt.

Participants in the EW condition were asked to write for 15–20 minutes about a heavy drinking experience that was negative for them. This paradigm has been associated with reduced drinking intentions in previous intervention trials (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2015; Young et al., 2013).

Measures

Demographics.

Participants were asked to report on their age, sex, year in school, height, weight, GPA, residence (on/off campus), Sorority/Fraternity membership, relationship status, ethnicity, racial background, religious affiliation, religious denomination, and work status.

Alcohol-related Problems.

The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) measured how often participants experienced negative alcohol-related consequences in the past month. Participants were asked how frequently they had personally experienced 25 alcohol-related consequences while drinking or because of their drinking. Example items include, “neglected your responsibilities”, “had a bad time”, and “caused shame or embarrassment to someone” (α = .93 at baseline; α = .97 at follow-up). Response options range from 1 (Never) to 5 (More than 10 times). The brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Kahler et al., 2005) evaluated alcohol-related problems using 24-items assessing a range of alcohol-related consequences students might have experienced over the past month. Example items include, “I have passed out from drinking” and “When drinking I have done impulsive things that I regretted later” (α = .89 at baseline, α = .91 at follow-up). Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they have experienced each of these consequences in the past month by responding ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each consequence.

Alcohol Use.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985; Kivlahan et al., 1990) assessed the number of standard drinks participants consumed each day during a typical week (Monday-Sunday) in the past month. A visual depiction of the equivalents of a standard drink of beer, wine, and liquor was displayed to cue participants to the size of a standard drink for each alcohol type (beer, malt liquor, wine, and liquor). Typical weekly drinking was calculated by summing the number of drinks reported each day of the week. The Quantity/Frequency Scale (QF; Baer, 1994; Marlatt et al., 1995) measured how many drinks were consumed on a peak drinking occasion within the past month.

Perceived Drinking Norms.

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer et al., 1991) evaluated perceived drinking norms with 11-items assessing beliefs regarding alcohol consumption behaviors for the typical, same-sex student from their university. Specifically, participants were asked how often and how much they think that the typical male (or female) student from their university drinks, as well as their estimates for what percentages of students abstain from drink, drink on one or fewer occasions per month, and never drink more than two drinks per occasion.

Attention Control Questionnaire.

Participants were asked how many hours they spend per week doing non-alcohol-related activities (e.g., studying, exercising, text messaging). Additionally, participants were asked how many hours they thought the typical same-sex university student engaged in each of these behaviors. Finally, they were asked if they play video games, what video game system they use, and what types of music they enjoy. This information was used to generate personalized feedback for the control condition.

Attrition

Of the 250 individuals who completed baseline, 169 completed follow-up (68%). To examine potential attrition effects, we created a dichotomous variable to distinguish individuals who completed follow-up from those who dropped out. We then examined attrition as a function of baseline demographics, norms, and outcome variables. Results from logistic regression analyses indicated that none of the variables were significantly related to drop out. Next, we examined whether there was differential attrition by condition. Logistic regression analyses revealed heavier drinkers (i.e., individuals who reported consuming more than the average number of drinks per week for the sample at baseline) were more likely to drop out of the PNF plus writing group compared to control (p = .05). A second follow-up was conducted six-months post-baseline. However, attrition was high (48%), potentially due to data collection occurring over the summer break when students were not available to complete the survey, and differed by condition such that individuals in the control group were more likely to drop out (EW n = 40, PNF n = 33, PNF+EW n = 32, Control n = 23). Thus, the six-month follow-up data were not retained. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used.

Plan of Analyses

Alcohol outcome variables were not normally distributed, so negative binomial distributions were specified for the models presented below. Additionally, latent variables were created for drinking with peak drinks and drinks per week as indicators and for problems with scores on the RAPI and the BYAACQ serving as indicators. Preliminary analyses explored whether there were baseline differences in norms, drinking, and alcohol-related problems between the conditions. All comparisons were non-significant (ps > .23). Correlational analyses were then run to understand basic associations among variables. Primary analyses were conducted in Mplus to evaluate whether the intervention was effective at reducing drinking and alcohol-related problems at the one-month follow-up. The four conditions were dummy coded to examine differences between conditions in predicting drinking and alcohol-related problems at one-month follow-up. Sex and baseline drinking outcomes were entered as covariates. Effect sizes d were calculated using the formula 2Z/sqrt(N), modified from 2t/sqrt(df) (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 2000).

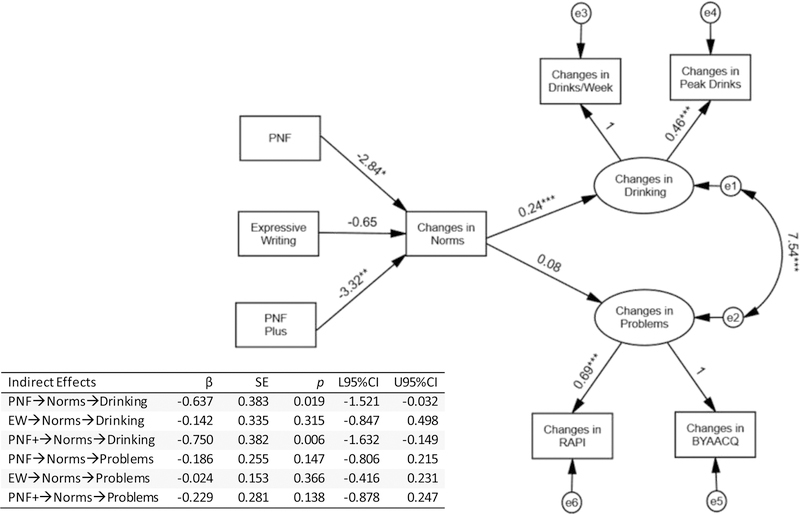

Mediation analyses were conducted to test whether intervention effects on changes in drinking and changes in alcohol-related problems were mediated by changes in perceived norms. Changes in drinking outcomes were operationalized as latent variable with residuals of follow-up drinking outcomes regressed on baseline drinking outcomes. Thus, the indicator for changes in drinks per week represented the portion of follow-up drinking not attributable to baseline drinking (i.e., residual change in drinking). Bayesian estimation with non-informative priors was used to evaluate indirect effects, defined by model constraints, in MPLUS 8. Results are based on 50,000 iterations. The absence of differences between observed and replicated chi-square values (CI:−21.98–33.72; p = .32) suggested reasonable fit. Tests of indirect effects are presented in Figure 2. Parameter estimates of indirect effects and confidence intervals are represented by the median and 95% confidence intervals of posterior distributions.

Figure 2.

Mediation of intervention effects on changes in alcohol outcomes through changes in perceived drinking norms.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Correlations, means, standard deviations, and ranges among variables are displayed in Table 1. Participants reported drinking an average of 7.63 drinks on their heaviest drinking occasion and 9.60 drinks per week, and thought that other same-sex students at their university drank an average of 12.74 drinks per week. Correlations revealed that sex was positively associated with perceived norms for weekly drinking, the average number of drinks consumed per week, and the peak number of drinks consumed, indicating that males tended to report drinking more than females. Furthermore, drinking outcomes were significantly positively associated with one another.

Table 1.

Correlations, means, standard deviations, and ranges among baseline variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | -- | .17** | .13* | .29*** | .09 | .06 |

| 2. Norms | -- | .65*** | .41*** | .19** | .17** | |

| 3. Drinks per week | -- | .55*** | .44*** | .39*** | ||

| 4. Peak drinks | -- | .36*** | .46*** | |||

| 5. RAPI score | -- | |||||

| 6. BYAACQ score | ||||||

| Mean | .30 | 12.74 | 9.60 | 7.63 | 7.13 | 5.22 |

| Standard Deviation | .46 | 9.29 | 8.76 | 4.44 | 10.73 | 4.70 |

| Minimum | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 80.00 | 79.00 | 25.00 | 71.00 | 23.00 |

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Intervention Effects on Alcohol-related Problems

Analyses examined whether the PNF plus writing condition was more effective at reducing alcohol-related problems at follow-up compared to all other conditions. Results revealed that the PNF plus writing condition significantly reduced alcohol-related problems at one-month follow-up relative to the three other conditions (PNF, EW, and control; see Table 2). When coded such that each intervention (PNF, PNFplus, and EW) was compared to control, again PNFplus significantly reduced alcohol-related problems at follow-up, but the other interventions did not (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Main effects of PNFplus versus all other conditions.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | Z | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Problems | PNFplus | −.545 | .261 | −2.09 | .036 | −.26 |

| Sex | −.130 | .292 | −.45 | .655 | −.06 | |

| Follow-up Drinking | PNFplus | −.077 | .171 | −.45 | .651 | −.06 |

| Sex | −.067 | .180 | −.37 | .709 | −.05 |

Table 3.

Main effects of each intervention condition compared to control.

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE B | Z | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up Problems | Expressive Writing | −.175 | .309 | −.57 | .571 | −.07 |

| PNF | −.338 | .371 | −.91 | .362 | −.12 | |

| PNFplus | −.683 | .321 | −2.13 | .033 | −.27 | |

| Sex | −.167 | .300 | −.56 | .577 | −.07 | |

| Follow-up Drinking | Expressive Writing | −.222 | .216 | −1.03 | .304 | −.13 |

| PNF | −.099 | .213 | −.47 | .641 | −.06 | |

| PNFplus | −.173 | .208 | −.83 | .405 | −.10 | |

| Sex | −.088 | .186 | −.47 | .636 | −.06 |

Intervention Effects on Alcohol Use

Analyses then examined whether the PNF plus writing condition was more effective at reducing drinking at one-month follow-up compared to each of the other conditions. Results revealed that the PNF plus writing condition did not significantly reduce alcohol consumption at follow-up relative to the three other conditions (PNF, EW, and control; p = .65). When coded such that each intervention (PNF, PNFplus, and EW) was compared to control, no significant reductions were found for alcohol consumption for any of the conditions relative to control (all ps > .30).

Intervention Effects on Perceived Norms

Paired samples t-tests were conducted to determine whether PNF and PNFplus reduced perceived descriptive norms for drinking relative to control. Both PNF, t(1, 166) = −2.16, p = .030, and PNFplus, t(1, 166) = −2.99, p = .003, were found to reduce perceived drinking norms at follow-up relative to control.

Mediation

Finally, a mediation model was evaluated examining changes in norms as a mediator of intervention effects on changes in drinking and changes in problems. Indirect effects represented paths from PNF, EW, and PNFplus to changes in drinking and problems through changes in perceived norms. Results, presented in Figure 2, indicated significant indirect effects of PNF and PNFplus, but not EW, on drinking through changes in perceived norms. No indirect effects of interventions on changes in alcohol-related problems through changes in norms were evident.

Discussion

The present study explored whether adding a writing component to a PNF intervention might improve intervention efficacy and whether expressive writing could be used as a standalone brief intervention to reduce drinking behavior. We expected the PNF plus writing intervention condition would show greater reductions in drinking and alcohol-related problems at one-month follow-up compared to the other conditions. We also expected that EW would lead to reductions in drinking and alcohol-related problems relative to control. Finally, we expected that changes in perceived norms would mediate intervention effects on both changes in drinking and alcohol-related problems. Results revealed that the PNF plus writing intervention significantly reduced alcohol-related problems at follow-up, but did not reduce drinking. Further, changes in perceived norms were found to mediate intervention effects for PNF and PNFplus on changes in drinking.

In contrast to previous studies, findings from the current study suggested that the interventions had no significant effects on consumption. In particular, the PNF and PNFplus conditions did not significantly reduce drinking. However, other studies utilizing remotely-delivered PNF have also found null results regarding reductions in drinking (e.g., Bernstein et al., 2018; Moreira et al., 2012). Unlike the results for alcohol-related problems, there were significant reductions in consumption among control group participants. Both the DDQ and QF, which were combined to create the latent drinking variable, capture past month drinking to test whether the intervention changed drinking over the upcoming month. No intervention effects were found on these variables. Further, consumption decreased in all conditions over the one-month period (EW: 9.2 to 4.9; PNF: 9.6 to 5.4; PNFplus 8.9 to 5.1; Control 10.6 to 6.0; see Table 4). This overall reduction in drinking may have resulted in an inability to detect whether the interventions had effects on drinking on these measures. Thus, drinking did decrease in the intervention conditions, just not differentially from the control condition. This might be due in part to subject reactivity. Clifford and Maisto (2000) suggested that assessing research participants’ drinking may confound treatment effects because they become more aware of their drinking as a result of the assessment. A more recent study found support for this theory such that individuals who were assessed less frequently showed worse treatment outcomes compared to those who were assessed more often (Clifford et al., 2007). Thus, drinking may have decreased in part due to the assessment of drinking and ensuing reflection on their drinking habits. Given that this only occurred for consumption (using measures derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire and the Quantity/Frequency Scale), this may have been exacerbated by asking students to specifically consider their drinking over the past month.

Table 4.

Estimated means (standard errors) and percent change from baseline to follow-up for each of the conditions on each of the outcome variables.

| Criterion | EW | (SE) | PNF | (SE) | PNF Plus | (SE) | Control | (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline RAPI | 6.97 | (1.50) | 7.45 | (1.59) | 10.47 | (2.23) | 7.93 | (1.74) |

| Follow-up RAPI | 3.81 | (.97) | 5.37 | (1.48) | 4.61 | (1.12) | 5.13 | (1.23) |

| Percent Change, Z test | −45.52% | −27.85% | −55.95% | −35.36% | ||||

| Z test | −2.81** | −1.33 | −4.10*** | −2.18* | ||||

| Baseline BYAACQ | 5.05 | (.72) | 5.94 | (.84) | 5.83 | (.82) | 5.39 | (.78) |

| Follow-up BYAACQ | 3.42 | (.60) | 4.14 | (.78) | 3.16 | (.54) | 4.37 | (.70) |

| Percent Change, Z test | −32.25% | −30.35% | −45.77% | −19.01% | ||||

| Z test | −2.36* | −2.03* | −3.89*** | −1.44 | ||||

| Baseline Drinks Per Week | 9.73 | (1.07) | 9.34 | (1.04) | 9.20 | (1.02) | 10.50 | (1.16) |

| Follow-up Drinks Per Week | 4.68 | (.66) | 5.28 | (.76) | 5.26 | (.71) | 5.90 | (.75) |

| Percent Change, Z test | −51.90% | −43.47% | −42.86% | −43.78% | ||||

| Z test | −5.39*** | −4.13*** | −4.29*** | −4.76*** | ||||

| Baseline Peak Drinks | 7.37 | (.56) | 7.60 | (.58) | 7.54 | (.57) | 7.89 | (.60) |

| Follow-up Peak Drinks | 4.32 | (.45) | 5.26 | (.54) | 4.14 | (.42) | 5.25 | (.49) |

| Percent Change, Z test | −51.90% | −43.47% | −42.86% | −43.78% | ||||

| Z test | −5.07*** | −3.63*** | −5.94*** | −4.40*** | ||||

| Baseline Perceived Norms | 13.72 | (1.09) | 11.28 | (.92) | 11.60 | (.94) | 13.91 | (1.12) |

| Follow-up Perceived Norms | 11.51 | (1.12) | 8.42 | (.90) | 7.80 | (.77) | 11.92 | (1.07) |

| Percent Change, Z test | −16.11% | −25.35% | −32.76% | −14.44% | ||||

| Z test | −1.82 | −2.72** | −3.99*** | −1.74 |

Another potential explanation for our findings is that drinking may have reduced due to the time of year in which the follow-up was conducted. Participants largely completed the intervention in November and December, thus the majority of follow-ups occurred over winter break. During this time, college students may have gone home for the break and may have reduced their drinking because their living circumstances changed. Because they were no longer in the college environment where heavy drinking is normative, they may have reduced their drinking to be more in line with their family’s drinking norms. However, research on event-specific drinking suggests that holidays serve as times for especially heavy and risky drinking, particularly New Year’s, a holiday included in most of the current study’s participants’ follow-ups (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2011). Also, this would not account for significant intervention effects on alcohol-related problems, as elaborated below.

While there were no significant effects of the interventions on drinking, results revealed significant reductions in alcohol-related problems. These results are similar to those found in a prior study aimed at improving cognitive processing surrounding personalized feedback (Jouriles et al., 2010) and is promising, as many brief interventions do not find significant reductions in alcohol-related problems, yet such problems are a primary cause for concern with regards to college student drinking. These results may seem contradictory; we found no significant reductions in drinking, but did find a significant reduction in alcohol-related problems. This is likely explained in part by the overall decrease in drinking we found that did not vary by condition. Thus, individuals in the intervention conditions did reduce their drinking, just not to a greater extent than the control group. However, it is notable that there was a significant effect for the PNFplus condition in reducing problems compared to all other conditions as well as compared to the control condition. Thus, adding a writing prompt to a PNF-based brief intervention may approximate the kinds of processing-based discussions that occur in a face-to-face feedback-based brief intervention. Perhaps writing about the feedback alerted individuals that their drinking was problematic and thus they thought more deeply about their drinking habits and, as a result, drank less problematically over the next month. Furthermore, because individuals may have more closely considered their drinking after participating in the study, they may have engaged in more protective behavioral strategies such as drinking water, spacing out drinks over a longer period of time, designating sober drivers, etc. to reduce their experience of negative alcohol-related consequences. Future tests of this paradigm might consider increased use of protective behavioral strategies as a potential mediator underlying the intervention effects on reduced alcohol-related problems.

Mediation analyses found significant indirect effects of PNF and PNFplus on changes in drinking through changes in perceived norms. When testing the mediation of PNF and PNFplus on changes in alcohol-related problems though changes in norms, results revealed that the indirect effects were non-significant. These findings are consistent with our expectations. Because the personalized feedback focused on specific comparisons between participants’ alcohol use and their peers’ alcohol use, we expected norms to mediate intervention effects on alcohol use. However, we did not expect that norms would mediate intervention effects on alcohol-related problems because the feedback did not make comparisons between participants’ and their peers’ experience of alcohol-related problems. Moreover, both PNF and PNFplus showed the expected indirect effect on changes in drinking through changes in perceived norms despite results indicating that the direct effect of intervention on changes in drinking was not significant. This provides some support for replication of the PNF effects seen in previous studies (e.g., LaBrie et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2007; Lojewski et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2016), albeit without a significant overall reduction of drinking by condition.

Finally, this study was the first test of expressive writing about a negative alcohol event as an intervention strategy for reducing drinking behavior. Previous work that adapted the expressive writing paradigm to focus on alcohol events found that writing about negative heavy drinking events led to immediate reductions in intentions to drink, but did not assess the intervention’s potential impact on actual drinking behavior (Rodriguez et al., 2015; Young et al., 2013). The present study did not find support for expressive writing as a brief intervention strategy for reducing problem drinking. The screening criteria used in the current study may have contributed to this failure to find effects as participants needed only to have had at least one heavy drinking event (4+ drinks for women, 5+ drinks for men in a single sitting) in the past month. Thus, it is possible that not all participants in the expressive writing condition had had a negative alcohol experience that they could write about, which may have limited the potential impact of the expressive writing intervention. Future investigations may include stricter inclusion criteria such that individuals must have previously experienced a negative alcohol event. Perhaps the transmission of effect from a single-session of expressive writing is very brief and was not captured by the one-month follow-up. It could be the case that expressive writing may be more effective as an additional component that may added to other empirically-supported interventions rather than a standalone intervention. Future studies may evaluate refinements of the writing prompt to promote behavior change.

Clinical Implications

The present findings suggest several avenues for clinical implications moving forward. First, expressive writing was not found to significantly reduce alcohol use and problems at one-month follow-up. This suggests that the current writing prompt may not be efficacious in reducing problem drinking and should be amended and tested further to determine whether such a paradigm can reduce drinking and problems. Next, results revealed that PNF plus writing did not reduce drinking, but did reduce alcohol-related problems, suggesting that the additional writing component may have some utility. While it is beyond the scope of the present investigation, linguistic analyses of the responses to the feedback using content coding and text-based software programs such as Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker et al., 2001) may also contribute to our understanding of why this brief intervention reduced alcohol-related problems.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had some limitations that are of note. First, the follow-up period was short; only one month. Future studies may wish to explore whether the intervention effects last beyond a one-month period. Next, there was differential attrition at follow-up such that heavier drinkers at baseline were more likely to drop out of the PNF plus writing condition relative to other conditions, which may have contributed to the present findings. Additionally, a larger sample size and less attrition at follow-up would lend more power to test intervention effects. Furthermore, this study was conducted within a couple of months and the follow-up period was during winter break. Due to this particular timing, students may have reduced their drinking as they went back to living with their parents over the break. However, this does not explain why intervention effects were found for alcohol-related problems. The writing prompts for the expressive writing and the PNFplus writing condition were different from each other and thus we cannot directly compare PNFplus writing to a writing only condition. However, the current study aim was twofold: to examine whether adding writing to a PNF intervention would reduce drinking and alcohol-related problems relative to traditional PNF and to test whether an emotion-based writing intervention would lead to reductions in actual alcohol use behaviors beyond drinking intentions. Future investigations may wish to further examine different writing prompts as a potential adjunct to a brief alcohol intervention. Participants were also volunteers from one college campus, which limits the generalizability of these findings. Future investigations may recruit participants over a longer time period to test for potential time of year effects. Future studies may consider implementing this intervention in-person to potentially boost intervention efficacy.

Conclusions

This study was the first of its kind to test the effect of adding a writing component to a PNF intervention. These results suggest that drinking was not reduced by the PNFplus intervention, or any other intervention, compared to control. Although the intervention did not reduce drinking, PNFplus reduced alcohol-related problems at follow-up. Thus, this intervention may have promise in targeting problematic drinking. Future investigations may explore why this have occurred and provide a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying this effect.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as the first author’s dissertation and was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA023495.

References

- Abbey A (2011) Alcohol’s role in sexual violence perpetration: theoretical explanations, existing evidence and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev 30:481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT (1998) Sexual assault perpetration by college men: the role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. J Soc Clin Psychol 177:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) The alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary care, 2:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS (1994) Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: an examination of the first year in college. Psychol Addict Behav 8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer ME (1991) Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. J Stud Alcohol 52:580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein MH, Stein LA, Neighbors C, Suffoletto B, Carey KB, Ferszt G, … Wood MD (2018) A text message intervention to reduce 21st birthday alcohol consumption: Evaluation of a two-group randomized controlled trial. Psychol Addict Behav 32:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB (2001) Peer influences on college drinking: a review of the research. J Subst Abuse 13:391–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LH, Correia CJ (2009) Brief alcohol intervention with college student drinkers: face-to face versus computerized feedback. Psychol Addict Behav 2:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan JM, Haeny AM, Martens MP, Weaver CC, Takamatsu SK, Arterberry BJ (2015) Personalized drinking feedback: a meta-analysis of in-person versus computer-delivered interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol, 83:430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo S, Brossard D, Frazer MS, Marchell T, Lewis D, Talbot J (2003) Are social norms campaigns really magic bullets? Assessing the effects of students’ misperceptions on drinking behavior. Health Commun 15:481–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo S, Cameron KA (2006) Differential effects of exposure to social norms campaigns: a cause for concern. Health Commun 19:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott‐Sheldon LAJ, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, Carey MP (2009) Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta‐analysis. Addiction 104:1807–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott‐Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS (2007) Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Addict Behav 32:2469–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S, Liberman A, Eagly AH (1989) Heuristic and systematic information processing within and beyond the persuasion context. In Uleman JS, & Bargh JA (Eds.), Unintended thought, (pp.212–252). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA (2000) Subject reactivity effects and alcohol treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol 61:787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA, Davis CM (2007) Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part I. Alcohol use and related consequences. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68:519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA (1985) Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the ffects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. JConsult Clin Psychol 53:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik FI, Lockhart RS (1972) Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J Verb Learn Verb Be 11:671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME (2011) Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Res-Curr Rev 34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA (2015) Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: a meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PloS One 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Hannah E (2008) Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: a web-based normative feedback program. J Subst Abuse Treat 34:263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW (2010) Magnitude and prevention of college drinking and related problems. Alcohol Res Health 33:45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman ER (2009) Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 16:12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Mun EY, Larimer ME, White HR, Ray AE, Rhew IC, … Atkins DC (2015) Brief motivational interventions for college student drinking may not be as powerful as we think: An individual participant‐level data meta‐analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:919–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA (2016) Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–55 Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 427 pp 30. [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Brown AS, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, Croft K, Leahy MM, Walters ST (2010) Improving the effectiveness of computer-delivered personalized drinking feedback interventions for college students. Psychol Addict Behav 24:592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP (2005) Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:1180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E (1990) Secondary prevention with college drinkers: evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. J Consult Clin Psychol 58:805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotailo PK, Egan J, Gangnon R, Brown D, Mundt M, Fleming M (2004) Validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test in college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Neighbors C, Zheng C, Kenney SR, ...Larimer ME (2013) RCT of web-based personalized normative feedback for college drinking prevention: are typical student norms good enough? J Consult Clin Psychol 81:1074–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM (2007) Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addict Behav 32: 2439–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C (2006) Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: a review of the research on personalized normative feedback. J Am Coll Health 54:213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C (2015) An examination of college student activities and attentiveness during a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Psychol Addict Behav 29:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME (2007) Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: personalized normative feedback and high risk drinking. Addict Behav, 32:2495–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lojewski R, Rotunda RJ, Arruda JE (2010) Personalized normative feedback to reduce drinking among college students: a social norms intervention examining gender-based versus standard feedback. J Alcohol Drug Educ 54:19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Larimer ME (1995) Preventing alcohol abuse in college students: a harm reduction approach. In: Boyd GM, Howard J, & Zucker RA, (Eds.), Alcohol problems among adolescents: Current directions in prevention research (147–172). Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira MT, Oskrochi R, Foxcroft DR (2012) Personalised normative feedback for preventing alcohol misuse in university students: Solomon three-group randomised controlled trial. PloS One 7:e44120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, ...Rodriguez LM (2011) Event-specific drinking among college students. Psychol Addict Behav, 25:702–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME (2010) Efficacy of Web-based personalized normative feedback: a two-year randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 78:898–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, LaBrie J, DiBello AM, Young CM, Rinker DV, Litt D, Rodriguez LM,…Larimer ME (2016) A multisite randomized trial of normative feedback for heavy drinking: social comparison versus social comparison plus correction of normative misperceptions. J Consult Clin Psychol 84:238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye EC, Agostinelli G, Smith JE (1999) Enhancing alcohol problem recognition: a self- regulation model for the effects of self-focusing and normative information. J Stud Alcohol 60:685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke HP, MacKinnon DP (2018) Reasons for testing mediation in the absence of an intervention effect: A research imperative in prevention and intervention research. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 79:171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Beall SK (1986) Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol 95: 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ (2001) Linguistic inquiry and word count: LIWC 2001. Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates 71, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT (1986) The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 19:123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Presley CA (1993) Alcohol and drugs on American college campuses: use, consequences, and perceptions of the campus environment Volume I: 1989–91. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR (2006) Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol 67:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, Van Straten A, Keuken M, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P (2009) Curbing problem drinking with personalized-feedback interventions: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 36:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Rinker DV, Lewis MA, Lazorwitz B, Gonzales RG, Larimer ME (2015) Remote vs. in-person computer-delivered personalized normative feedback interventions for college student drinking. J Consult Clin Psych 83:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Young CM, Neighbors C, Campbell MT, Lu Q (2015) Evaluating shame and guilt in an expressive writing alcohol intervention. Alcohol 49: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal SR, Clark MA, Marshall BD, Buka SL, Carey KB, Shepardson RL, Carey MP (2018) Alcohol consequences, not quantity, predict major depression onset among first-year female college students. Addict Behav 85: 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL, & Rubin DB (2000). Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spera SP, Buhrfeind ED, Pennebaker JW (1994) Expressive writing and coping with job loss. Acad Manage J 37:722–733. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C (2005) Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom?. Addict Behav 30:1168–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN (2009) Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psych 77:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H (1998) Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997. J Am Coll Health 47:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM (2003) What happened? Alcohol, memory blackouts, and the brain. Alcohol Res Health 27:186–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Hingson R (2013) The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res-Curr Rev 35:201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW (1989) Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol 50:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Mun EY, Pugh L, Morgan TJ (2007) Long‐term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: Sleeper effects of an in‐person personal feedback intervention. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31:1380–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CM, Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C (2013) Expressive writing as a brief intervention for reducing drinking intentions. Addict Behav 38: 2913–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]