Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium that thrives in nature as a saprophyte and in the mammalian host as an intracellular pathogen. Both environments pose potential danger in the form of redox stress. In addition, endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) are continuously generated as by-products of aerobic metabolism. Redox stress from ROS can damage proteins, lipids, and DNA, making it highly advantageous for bacteria to evolve mechanisms to sense and detoxify ROS. This review focuses on the five redox-responsive regulators in Lm: OhrR (to sense organic hydroperoxides), PerR (peroxides), Rex (NAD+/NADH homeostasis), SpxA1/2 (disulfide stress), and PrfA (redox stress during infection).

Introduction

Detoxification, avoidance, or destruction: these are the possible outcomes when bacteria encounter redox stress. Redox stress refers to an imbalance in reductive and oxidative species, which is often caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS, including hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals, are generated endogenously during aerobic respiration and exogenously by the host respiratory burst during infection [1]. In addition, ROS are generated in the environment by chemical and photochemical processes, as well as by plants and bacteria that excrete redox-cycling compounds to kill competitors [2,3]. The severity of potential defects caused by altered redox homeostasis explains why bacteria have evolved myriad mechanisms to sense and detoxify ROS, as well as repair oxidatively damaged DNA, proteins, and lipids. The ability of pathogenic bacteria to inhabit the host environment is then, in part, determined by bacterial defenses against ROS and other redox stressors found in the host.

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) is a Gram-positive, foodborne bacterium that thrives in dramatically distinct environments during its transition from saprophyte to cytosolic pathogen [4]. The intracellular lifecycle of Lm requires it to survive the harsh phagosomal compartment, escape into the highly reducing cytosol, and spread to neighboring cells. To survive these changing environmental conditions, Lm encodes dozens of transcriptional regulators that each sense a distinct stimulus to modulate expression of specific genes appropriately. In this review, we focus on the five redox-responsive regulators and describe how they enable Lm to adapt to changing redox conditions in nature and during pathogenesis.

OhrR: Organic hydroperoxide stress

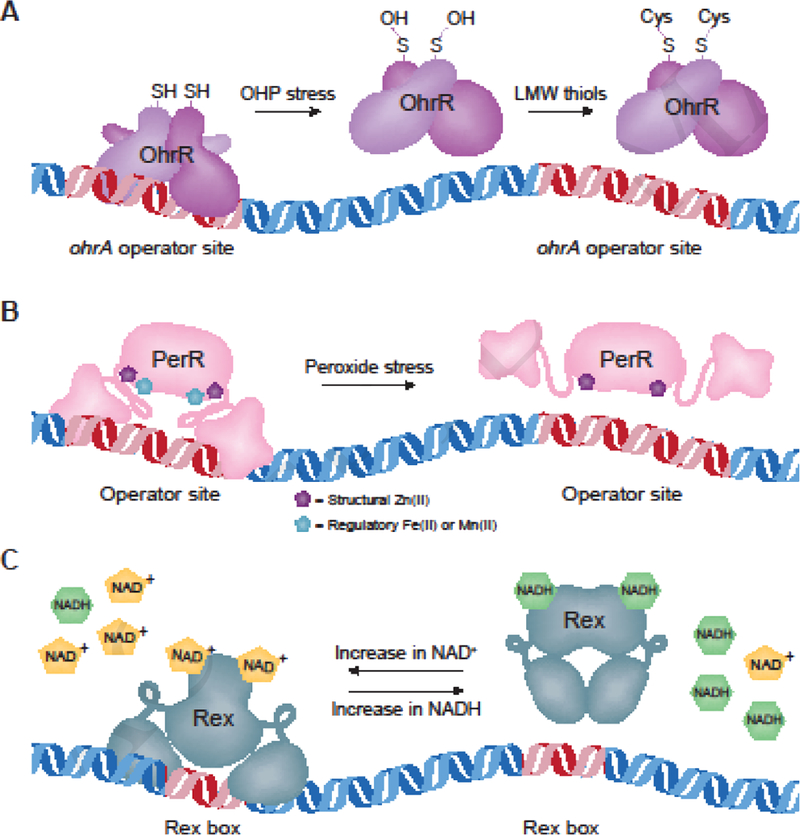

Organic hydroperoxides (OHPs), such as cumene HP and tert-butyl HP, are derived from fatty acids and steroids and are strong oxidizers that readily generate free radicals. When bacteria encounter OHPs, peroxiredoxins in the OsmC/OhrA family detoxify these dangerous compounds by reducing them to their corresponding alcohols in order to prevent damage to cellular macromolecules. OhrA peroxiredoxins are commonly regulated by redox-responsive transcriptional repressors of the MarR-family named OhrR. In the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis, OhrR regulates OhrA, which shares 63% similarity to Lm OhrA [5]. B. subtilis OhrR is a functional dimer that senses OHPs via S-thiolation at a conserved cysteine residue [6]. S-thiolated OhrR dissociates from DNA, resulting in derepression of ohrA transcription and relief from OHP stress (Fig. 1A). Lm ohrA is encoded in an operon with a transcriptional regulator that has 68% amino acid similarity to B. subtilis OhrR [7].

Figure 1. Redox-regulated repressors.

Schematic depicting the functions of OhrR, PerR, and Rex. Red DNA represents specific DNA-binding sequences recognized by each transcriptional repressor. A. Dimerized, reduced OhrR binds to specific DNA sequences and represses downstream genes. OHP stress oxidizes a cysteine residue on each monomer to sulfenic acid (-OH). This can then be S- thiolated by the low-molecular-weight thiols cysteine or glutathione, resulting in nonfunctional protein and derepression of ohrA [42,43]. B. In the absence of stress and in the presence of sufficient metals, PerR binds to DNA and represses expression of target genes [9]. Peroxide induces oxidation of Fe(II)- bound PerR, altering the conformation such that it releases from the DNA and the PerR regulon is derepressed [15]. Oxidized PerR is then targeted for degradation [11]. Dysregulation of the PerR regulon also occurs in conditions of excess Zn(II) or Mn(II) [44]. C. When NAD+ concentrations are sufficient, Rex represses target genes by binding a specific DNA sequence, referred to as a ‘Rex box’. However, as NADH increases, it competes with NAD+ for binding to Rex and NADH-bound protein does not bind DNA, thereby relieving repression of the Rex regulon [18].

Infected macrophages produce abundant phagosomal OHPs, requiring intracellular pathogens to detoxify them. For example, Mycobacterium smegmatis ohrA is derepressed in this environment, suggesting that OhrR is oxidized during infection [8]. Further, the Lm ΔohrA mutant exhibits a growth defect in macrophages that may be due to host-derived OHP toxicity. In addition to its role in detoxifying OHPs, OhrA was identified as being required for proper regulation of virulence factors during Lm infection [7]. These findings demonstrate that OhrA is important for OHP detoxification in Lm, and that redox regulation is tied to virulence gene regulation.

PerR: Peroxide stress

Hydrogen peroxide is generated endogenously from incomplete reduction of oxygen during aerobic respiration, and produced exogenously by the mammalian host to kill invading pathogens [1]. Peroxides exert their toxicity through the oxidation of iron-sulfur clusters and cysteine residues [9]. Consequently, bacteria possess mechanisms to directly sense peroxides and up-regulate genes required for their detoxification. The primary peroxide-sensing transcriptional repressor in Firmicutes is PerR, which normally binds DNA and represses transcription of target genes (Fig. 1B). The irreversible oxidation of two PerR histidine residues upon peroxide exposure leads to its degradation and derepression of its regulon [10,11]. Genes repressed by Lm PerR include the iron homeostasis regulator (fur), catalase (kat), heme biosynthesis machinery (hemA), an iron efflux pump (fvrA), the iron storage protein (fri), thioredoxin reductase (trxB), and a predicted peroxiredoxin (lmo1604) [12].

It is clear from the PerR regulon that the response to peroxide stress is intimately intertwined with metal homeostasis. Indeed, PerR has two metal-binding sites upon which PerR activity depends: the first is a structural Zn(II)-binding site and the second binds Fe(II) or Mn(II) and serves a regulatory function [13]. Mn(II)-bound PerR represses transcription of fur and perR itself, while Fe(II)-bound PerR represses peroxide-detoxification genes [14]. Thus, the iron status of the cell directly regulates PerR activity [15]. During peroxide stress, iron-catalyzed oxidation of PerR histidine residues results in dissociation of the regulatory metal ions and derepression of the PerR regulon. The regulation of Fur and iron homeostasis is therefore critical to redox homeostasis. Although we will not expand on Fur in this review as it is not a canonical redox-regulator, its importance cannot be overlooked.

Lm strains lacking perR form small colonies on rich media and exhibit increased sensitivity to peroxide stress, suggesting important roles for PerR in both routine detoxification of endogenously produced peroxides as well as exogenous ROS stress [12]. These growth defects are due in part to iron starvation that results from derepression of the PerR regulon; specifically, increased Fur expression and repression of iron-acquisition genes [15]. The ΔperR strain was also attenuated 100-fold in a murine model of infection [12]. Together, these phenotypes demonstrate the importance of peroxide-sensing to Lm survival and pathogenesis.

Rex: NAD+/NADH levels

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) exists in the oxidized (NAD+) or reduced (NADH) state and is a coenzyme critical for cellular redox reactions. The ratio of NAD+ to NADH is a measure of the redox state of the cell and must be carefully regulated to maintain homeostasis. To monitor this balance, many low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria encode the transcriptional repressor Rex (Fig. 1C), which directly senses the NADH:NAD+ ratio to regulate carbohydrate and energy metabolism [16]. Although Rex has not yet been studied in Lm, the protein (encoded by lmo2072) is highly similar to its homologues in B. subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, sharing 65% and 52% amino acid identity, respectively. In these bacteria, Rex binds a specific DNA consensus sequence to repress target genes under basal growth conditions when NAD+ concentrations are relatively high [14,15]. In contrast, NADH-bound Rex is unable to bind DNA, thus relieving repression of its regulon when NADH is more abundant. For example, high NAD+ levels in B. subtilis result in Rex repression of ndh (encoding NADH dehydrogenase), which decreases NADH oxidation to restore homeostasis [17]. In addition to NADH dehydrogenase, the Rex regulon typically includes genes encoding lactate dehydrogenase, pyruvate formate lyase, respiratory nitrate reductase, and cytochrome oxidases [18]. A bioinformatics approach to understanding Rex function in 119 bacterial genomes found considerable variability in Rex-dependent genes, likely corresponding to the different niches of individual species [16]. Therefore, while we can make predictions about Rex function in Lm, its regulon and role during infection remain to be experimentally determined.

SpxA1/2: Disulfide stress

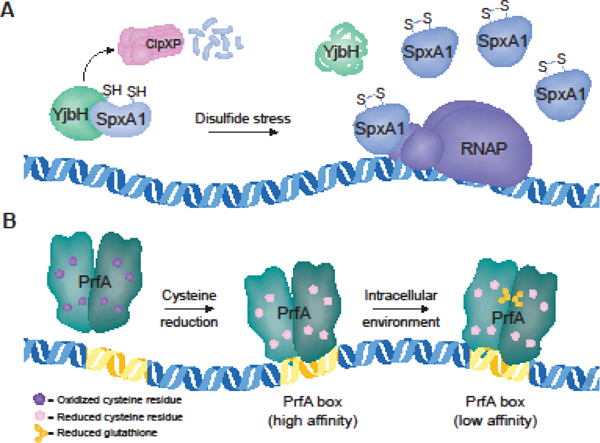

Disulfide stress is characterized by the oxidation of cysteine residues, resulting in irreversible overoxidation or erroneous intra- and intermolecular disulfide bridges that induce conformational changes in thiol-containing proteins [19]. The arsenate reductase (ArsC) family transcriptional regulator Spx is widely conserved throughout Firmicutes and detects disulfide stress through its N-terminal Cys-x-x-Cys redox switch [20]. The abundance and activity of Spx are tightly regulated to control the disulfide stress response [21]. In B. subtilis, Spx protein concentrations are kept low by ClpXP-mediated proteolysis, which requires the protease adaptor YjbH [22,23]. YjbH is a relatively unstable protein that aggregates in response to stress, including disulfide stress. The lowered abundance of YjbH during disulfide stress effectively increases Spx concentrations, as it is less efficiently degraded by ClpXP in the absence of YjbH [24]. Oxidative stress also induces an intramolecular disulfide bond in the Spx CxxC redox switch, altering its conformation such that it interacts with RNA polymerase to regulate downstream genes (Fig. 2A) [25,26]. In B. subtilis, oxidized Spx activates over 100 genes involved in maintaining redox homeostasis (e.g.: thioredoxin, bacillithiol biosynthesis, and oxidoreductases), and represses approximately 170 genes involved in energy-consuming functions [27,28].

Figure 2. Redox-regulated activators.

Schematic depicting the functions of SpxA1 and PrfA. A. SpxA1 can activate or repress target genes. In the absence of stress, SpxA1 abundance is kept low by ClpXP-mediated degradation, which requires the protease adaptor protein YjbH [23]. Disulfide stress induces YjbH aggregation, resulting in increased SpxA1 abundance. SpxA1 does not possess DNA-binding activity on its own, but regulates target genes through its interaction with the αCTD of RNA polymerase [45]. B. PrfA is a homodimer that binds to a 14-bp palindromic repeat referred to as a ‘PrfA box’. Reduction of the protein thiols allows PrfA to bind to high-affinity PrfA boxes containing perfect palindromic sequences [32]. During infection, allosteric binding of glutathione to PrfA induces the active conformation that promotes transcription of all PrfA boxes [39].

Lm encodes two Spx paralogues named SpxA1 and SpxA2 that share 56% amino acid similarity. While SpxA1 is essential for Lm aerobic growth and pathogenesis, a ΔspxA2 mutant exhibits only slightly impaired growth in vitro and is fully virulent in mice [29]. Strikingly, a strain lacking spxA1 can only be generated anaerobically and is killed upon exposure to oxygen [29]. B. subtilis Spx functionally complements the Lm ΔspxA1 mutant, demonstrating that the physical interaction with RNA polymerase is conserved between Lm and B. subtilis [29]. However, given the severe defects of the ΔspxA1 mutant, the Lm SpxA1 regulon must be distinct from that of B. subtilis Spx, which is not required for growth.

Lm ΔspxA1 replicates in macrophages, suggesting that either Lm experiences oxygen deprivation in the host cytosol, or host cytosol components can restore ΔspxA1 growth. Intriguingly, ΔspxA1 colonizes the spleens of infected mice but is nearly sterilized from the livers [29]. These data suggest that Lm experiences organ-specific differences in redox stress and/or oxygen concentrations during infection and that SpxA1-dependent genes are differentially essential in host microenvironments. The host factor(s) that contribute to ΔspxA1 intracellular growth and pathogenesis have not yet been investigated. Additionally, identifying the SpxA1 regulon will elucidate the genes required for aerobic growth extracellularly and those necessary for intracellular growth in the mammalian host.

PrfA: Pathogenesis

PrfA is known as the ‘master virulence regulator’ in Lm, as it directly activates all nine virulence genes and indirectly regulates over 140 additional genes [30,31]. PrfA is absolutely essential for virulence and a ΔprfA mutant is attenuated over four-logs in a murine infection model [32]. Conversely, constitutive PrfA activation results in significantly decreased extracellular growth [33], highlighting the requirement for appropriately localized PrfA activation specifically in the intracellular compartment. To that end, PrfA is regulated transcriptionally by multiple promoter regions [34,35], post-transcriptionally by a temperature-sensitive riboswitch and a 5’ untranslated region [36,37], and post-translationally by an allosteric ligand that modulates the activation state of PrfA [38].

PrfA is a member of the cAMP receptor protein family, which is characterized by allosteric activation by a small molecule cofactor. It was recently determined that the abundant low-molecular-weight thiol glutathione is the allosteric activator of PrfA [32]. Reduced glutathione binds PrfA in an intraprotein tunnel region previously predicted to be the site of ‘activator’ binding [39,40]. Upon binding to reduced glutathione, PrfA undergoes a slight conformational shift that promotes DNA binding and transcriptional activation. PrfA activation is further regulated by the redox state of the environment via its four cysteine residues: all eight thiols of the PrfA homodimer must be in the reduced state for PrfA to bind DNA [32]. Together, these findings suggest a model in which PrfA is reduced upon Lm entering the host cytosol, enabling it to bind DNA. Bacterial- or host-derived glutathione then binds and activates PrfA, promoting transcription of virulence genes (Fig. 2B).

Importantly, PrfA activation is also closely connected to the metabolic changes that occur as Lm shifts from a saprophytic to parasitic lifestyle. The most apparent example of this is the hexose phosphate transporter, directly regulated by PrfA, which enables Lm to take up glucose-6-phosphate from the host cytosol [41]. PrfA activity is high when grown in the presence of carbohydrates abundant in the mammalian cytosol, such as glycerol or glucose-6-phosphate, although the exact molecular mechanism of this regulation is unknown. In contrast, PrfA activity is repressed in the presence of carbon sources commonly found outside the host environment, such as plant-derived cellobiose [4]. Therefore, as Lm switches to a virulent state, its metabolic reprogramming is redox-regulated via PrfA activity.

Conclusion

Without mechanisms to sense and respond to ROS and other redox stressors, bacteria would fall prey to oxidative damage, resulting in hypermutation or death. Lm is a particularly resilient intracellular pathogen, able to monitor and detoxify many varied ROS. This resiliency is critical to the ability of Lm—and other pathogens—to cause disease. During the process of infection, for example, Lm encounters diverse environments that each pose distinct danger. As a foodborne pathogen, Lm is first exposed to ROS that are produced via iron chemistry in the mammalian gut [42]. Upon entering host cells Lm must survive the oxidative burst in the phagosome, escape into the reduced cytosol, and spread to neighboring cells [43]. If the infection becomes systemic, Lm can colonize nearly every organ, each of which may differ in their inherent redox stress levels (see “SpxA1/2: Disulfide stress”). There remains much to be learned about redox-responsive regulators in Lm, but the work summarized in this review is representative of an excellent knowledge base. Ongoing research in this field will help illuminate the exact mechanisms by which Lm occupies both the soil and the intracellular niche so successfully.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Reniere Lab for critical reading of this review. We also apologize to colleagues that were not cited due to length constraints. Research in the Reniere lab is funded by the National Institutes of Health [grant RO1 AI132356]. B.R.R. is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [PHS NRSA T32GM007270].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Reniere ML: Reduce, Induce, Thrive: Bacterial Redox Sensing during Pathogenesis. J Bacteriol 2018, 200:903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imlay JA: Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77:755–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra S, Imlay JA: Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2012, 525:145–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD: Listeria monocytogenes - from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009, 7:623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuangthong M, Atichartpongkul S, Mongkolsuk S, Helmann JD: OhrR is a repressor of ohrA, a key organic hydroperoxide resistance determinant in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2001, 183:4134–4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J-W, Soonsanga S, Helmann JD: A complex thiolate switch regulates the Bacillus subtilis organic peroxide sensor OhrR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104:8743–8748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reniere ML, Whiteley AT, Portnoy DA: An In Vivo Selection Identifies Listeria monocytogenes Genes Required to Sense the Intracellular Environment and Activate Virulence Factor Expression. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12:e1005741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garnica OA, Das K, Dhandayuthapani S: OhrR of Mycobacterium smegmatis senses and responds to intracellular organic hydroperoxide stress. Scientific Reports 2017, 7:3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imlay JA: Transcription Factors That Defend Bacteria Against Reactive Oxygen Species. Annu Rev Microbiol 2015, 69:93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J-W, Helmann JD: The PerR transcription factor senses H2O2 by metal-catalysed histidine oxidation. Nature 2006, 440:363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn B-E, Baker TA: Oxidization without substrate unfolding triggers proteolysis of the peroxide-sensor, PerR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113:E23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rea R, Hill C, Gahan CGM: Listeria monocytogenes PerR mutants display a small-colony phenotype, increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide, and significantly reduced murine virulence. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71:8314–8322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J-W, Helmann JD: Biochemical characterization of the structural Zn2+ site in the Bacillus subtilis peroxide sensor PerR. J Biol Chem 2006, 281:23567–23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuangthong M, Herbig AF, Bsat N, Helmann JD: Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis fur and perR genes by PerR: not all members of the PerR regulon are peroxide inducible. J Bacteriol 2002, 184:3276–3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faulkner MJ, Ma Z, Fuangthong M, Helmann JD: Derepression of the Bacillus subtilis PerR peroxide stress response leads to iron deficiency. J Bacteriol 2012, 194:1226–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravcheev DA, Li X, Latif H, Zengler K, Leyn SA, Korostelev YD, Kazakov AE, Novichkov PS, Osterman AL, Rodionov DA: Transcriptional regulation of central carbon and energy metabolism in bacteria by redox-responsive repressor Rex. J Bacteriol 2012, 194:1145–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyan S, Shiohira Y, Sato I, Takeuchi M, Sato T: Regulatory loop between redox sensing of the NADH/NAD(+) ratio by Rex (YdiH) and oxidation of NADH by NADH dehydrogenase Ndh in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2006, 188:7062–7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson AR, Somerville GA, Sonenshein AL: Regulating the Intersection of Metabolism and Pathogenesis in Gram-positive Bacteria. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3:129–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landeta C, Boyd D, Beckwith J: Disulfide bond formation in prokaryotes. Nat Microbiol 2018, 3:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuber P: Management of oxidative stress in Bacillus. Annu Rev Microbiol 2009, 63:575–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillion M, Antelmann H: Thiol-based redox switches in prokaryotes. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396:415–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg SK, Kommineni S, Henslee L, Zhang Y, Zuber P: The YjbH protein of Bacillus subtilis enhances ClpXP-catalyzed proteolysis of Spx. J Bacteriol 2009, 191:1268–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsson JT, Rogstam A, Wachenfeldt von C: YjbH is a novel negative effector of the disulphide stress regulator, Spx, in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 2007, 66:669–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engman J, Wachenfeldt von C: Regulated protein aggregation: a mechanism to control the activity of the ClpXP adaptor protein YjbH. Mol Microbiol 2015, 95:51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birch CA, Davis MJ, Mbengi L, Zuber P: Exploring the Amino Acid Residue Requirements of the RNA Polymerase (RNAP) a Subunit C-Terminal Domain for Productive Interaction between Spx and RNAP of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2017, 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakano S, Erwin KN, Ralle M, Zuber P: Redox-sensitive transcriptional control by a thiol/disulphide switch in the global regulator, Spx. Mol Microbiol 2005, 55:498–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rochat T, Nicolas P, Delumeau O, Rabatinova A, Korelusova J, Leduc A, Bessieres P, Dervyn E, Krasny L, Noirot P: Genome-wide identification of genes directly regulated by the pleiotropic transcription factor Spx in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40:9571–9583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakano S, Küster-Schöck E, Grossman AD, Zuber P: Spx-dependent global transcriptional control is induced by thiol-specific oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100:13603–13608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whiteley AT, Ruhland BR, Edrozo MB, Reniere ML: A Redox-Responsive Transcription Factor Is Critical for Pathogenesis and Aerobic Growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 2017, 85:e00978–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milohanic E, Glaser P, Coppee J-Y, Frangeul L, Vega Y, Vazquez-Boland JA, Kunst F, Cossart P, Buchrieser C: Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes identifies three groups of genes differently regulated by PrfA. Mol Microbiol 2003, 47:1613–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.las Heras de A, Cain RJ, Bielecka MK, Vazquez-Boland JA: Regulation of Listeria virulence: PrfA master and commander. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011, 14:118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reniere ML, Whiteley AT, Hamilton KL, John SM, Lauer P, Brennan RG, Portnoy DA: Glutathione activates virulence gene expression of an intracellular pathogen. Nature 2015, 517:170–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasanthakrishnan RB, las Heras de A, Scortti M, Deshayes C, Colegrave N, Vazquez-Boland JA: PrfA regulation offsets the cost of Listeria virulence outside the host. Environ Microbiol 2015, doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freitag NE, Portnoy DA: Dual promoters of the Listeria monocytogenes prfA transcriptional activator appear essential in vitro but are redundant in vivo. Mol Microbiol 1994, 12:845–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mengaud J, Dramsi S, Gouin E, Vazquez-Boland JA, Milon G, Cossart P: Pleiotropic control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors by a gene that is autoregulated. Mol Microbiol 1991, 5:2273–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson J, Mandin P, Renzoni A, Chiaruttini C, Springer M, Cossart P: An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 2002, 110:551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong KKY, Bouwer HGA, Freitag NE: Evidence implicating the 5’ untranslated region of Listeria monocytogenes actA in the regulation of bacterial actin-based motility. Cell Microbiol 2004, 6:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xayarath B, Freitag NE: Optimizing the balance between host and environmental survival skills: lessons learned from Listeria monocytogenes. Future Microbiol 2012, 7:839–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall M, Grundström C, Begum A, Lindberg MJ, Sauer UH, Almqvist F, Johansson J, Sauer-Eriksson AE: Structural basis for glutathione-mediated activation of the virulence regulatory protein PrfA in Listeria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113:201614028–14738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Feng H, Zhu Y, Gao P: Structural insights into glutathione-mediated activation of the master regulator PrfA in Listeria monocytogenes. Protein Cell 2017, 8:308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chico-Calero I, Suarez M, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Scortti M, Slaghuis J, Goebel W, European Listeria Genome Consortium, Vazquez-Boland JA: Hpt, a bacterial homolog of the microsomal glucose- 6-phosphate translocase, mediates rapid intracellular proliferation in Listeria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99:431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kortman GAM, Raffatellu M, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H: Nutritional iron turned inside out: intestinal stress from a gut microbial perspective. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014, 38:1202–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFarland AP, Burke TP, Carletti AA, Glover RC, Tabakh H, Welch MD, Woodward JJ: RECON- Dependent Inflammation in Hepatocytes Enhances Listeria monocytogenes Cell-to-Cell Spread. MBio 2018, 9:433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chandrangsu P, Helmann JD: Intracellular Zn(II) Intoxication Leads to Dysregulation of the PerR Regulon Resulting in Heme Toxicity in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet 2016, 12:e1006515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newberry KJ, Nakano S, Zuber P, Brennan RG: Crystal structure of the Bacillus subtilis anti-alpha, global transcriptional regulator, Spx, in complex with the alpha C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102:15839–15844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]