Abstract

Objective

To compare early routine pharmacologic treatment of moderate-to-large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at the end of week 1 with a conservative approach that requires prespecified respiratory and hemodynamic criteria before treatment can be given.

Study design

A total of 202 neonates of <28 weeks of gestation age (mean, 25.8 ± 1.1 weeks) with moderate-to-large PDA shunts were enrolled between age 6 and 14 days (mean, 8.1 ± 2.2 days) into an exploratory randomized controlled trial.

Results

At enrollment, 49% of the patients were intubated and 48% required nasal ventilation or continuous positive airway pressure. There were no differences between the groups in either our primary outcome of ligation or presence of a PDA at discharge (early routine treatment [ERT], 32%; conservative treatment [CT], 39%) or any of our prespecified secondary outcomes of necrotizing enterocolitis (ERT, 16%; CT, 19%), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (ERT, 49%; CT, 53%), BPD/death (ERT, 58%; CT, 57%), death (ERT,19%; CT, 10%), and weekly need for respiratory support. Fewer infants in the ERT group met the rescue criteria (ERT, 31%; CT, 62%). In secondary exploratory analyses, infants receiving ERT had significantly less need for inotropic support (ERT, 13%; CT, 25%). However, among infants who were ≥26 weeks gestational age, those receiving ERT took significantly longer to achieve enteral feeding of 120 mL/kg/day (median: ERT, 14 days [range, 4.5-19 days]; CT, 6 days [range, 3-14 days]), and had significantly higher incidences of late-onset non-coagulase-negative Staphylococcus bacteremia (ERT, 24%; CT,6%) and death (ERT, 16%; CT, 2%).

Conclusions

In preterm infants age <28 weeks with moderate-to-large PDAs who were receiving respiratory support after the first week, ERT did not reduce PDA ligations or the presence of a PDA at discharge and did not improve any of the prespecified secondary outcomes, but delayed full feeding and was associated with higher rates of late-onset sepsis and death in infants born at ≥26 weeks of gestation.

Trial registration

Most preterm infants at ≥28 weeks of gestation spontaneously close the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) by the end of the first postnatal week.1,2 In contrast, 50%-70% of infants at <28 weeks of gestation have a moderate-to-large PDA shunt that persists for weeks after birth.3 A moderate-to-large PDA shunt can decrease systemic blood pressure, reduce blood flow to systemic organs, increase pulmonary blood pressure and flow, increase lung water, and decrease lung compliance.4–15 Prophylactic or early pharmacologic PDA closure can decrease the incidence of several neonatal morbidities that occur during the first week after birth, including dopamine-dependent hypotension, early hemorrhagic pulmonary edema, and intensity of respiratory support.7,8,16–18

Whether exposure to a moderate-to-large PDA shunt increases the risks of later neonatal morbidities, like bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), is unclear. Previous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that later morbidities are not increased by short-term PDA exposures (ie, for 3-4 days after birth).17,19–22 Unfortunately, conclusions from these studies about the effects of more prolonged exposure have been confounded by high rates of early spontaneous PDA closure, early use of rescue treatments, and failure to consider the effects of different PDA shunt magnitudes.8,17,19–21,23

The previous RCTs that examined the effects of routine PDA treatment enrolled infants within the first few days after birth. One of the major challenges these trials faced was the fact that the PDA closed spontaneously before the end of the first week in at least 30%-40% of patients enrolled into the conservative or “no treatment” arm of these studies.1,2 Therefore, we designed the PDA-TOLERATE trial as a pilot exploratory trial to test the hypothesis that routine treatment of a moderate-to-large PDA that was likely to persist for several weeks would reduce neonatal morbidity compared with a conservative approach that delayed treatment until prespecified respiratory and hemodynamic “rescue” criteria were met. To enroll only those infants with moderate-to-large PDA shunts that were likely to persist for weeks and to avoid enrolling infants who might experience spontaneous PDA constriction within a few days of enrollment, we chose to wait until the end of the first week before evaluating and enrolling the infants.

Because this RCT explored the effects of prolonged exposure to moderate-to-large PDA shunts in infants <28 weeks gestation, we considered it to be an exploratory trial. We planned to enroll only 200 patients. Our primary outcome was the need for ligation or the need for PDA cardiology followup after discharge. We also gathered information about serious neonatal morbidities and the need for additional therapies and present their results descriptively as secondary outcomes to generate hypotheses for appropriately powered future large-scale RCTs.

Methods

This prospective RCT was conducted between January 2014 and June 2017 at 17 international sites after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval at each site. Written informed parental consent was obtained before enrollment. Additional scientific review of the trial protocol was provided by the Gerber Foundation, and the trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01958320). Infants were eligible for the study if they met all 3 of the following conditions: (1) age 6-14 days (day of birth = day 0) if delivered between weeks 230/7 and 256/7 or 8-14 days if delivered between weeks 260/7 and 276/7, (2) a moderate-to-large PDA (see below for criteria), and (3) receipt of greater than minimal respiratory support, defined as positive-pressure ventilation, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), or high-flow nasal cannula support with flow rate >2 L/minute and fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) >0.25. Eligible infants were excluded from participation if they had received previous treatment with indomethacin or ibuprofen, had a chromosomal anomaly, a congenital or acquired gastrointestinal anomaly, previous episodes of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or intestinal perforation, active pulmonary hemorrhage at the time of enrollment, or contraindications to the use of indomethacin or ibuprofen (eg, hydrocortisone administration in the previous 24 hours, urine output < 1 mL/kg/hour during preceding 8 hours, serum creatinine >1.6 mg/dL, platelet count <50 000/mm3, or abnormal coagulation studies). Sixteen of the 17 centers also excluded infants who needed inotropic support for hypotension at the time of enrollment.

The echocardiographic studies included 2-dimensional imaging, M-mode, color flow mapping, and Doppler interrogation as described previously.24,25 A moderate-to-large PDA was defined as an internal ductus diameter ≥1.5 mm (or a PDA:left pulmonary artery diameter ≥0.5) and 1 or more of the following echocardiographic criteria: (1) left atrium-to-aortic root ratio ≥1.6, (2) ductus flow velocity ≤2.5 m/second or mean pressure gradient across the ductus ≤8 mmHg, (3) left pulmonary artery diastolic flow velocity > 0.2 m/second, and/or (5) reversed diastolic flow in the descending aorta. A ductus that failed to meet these criteria was considered “constricted” (small or closed) and ineligible for enrollment or treatment.

Randomization was stratified by gestational age (230/7-256/7 or 260/7-276/7) and by center. Block randomization (in blocks of 2) was done at each site for each gestational age group with an allocation of 1:1. Blinded randomization was assigned sequentially from sealed envelopes.

Our trial was a pragmatic RCT. Infants randomized to the early routine treatment (ERT) group received either indomethacin, ibuprofen, or acetaminophen (with indomethacin backup if the PDA failed to constrict after the initial treatment) (drug protocols, Figure 1; available atwww.jpeds.com). Because the drugs appear to have similar efficacies in closing the PDA,26 the choice of drug treatment was left to each center according to its standard practice. After completing the initial treatment, infants were followed to determine if they met eligibility criteria for “rescue” treatment (see below). The rescue treatment was the same drug treatment protocol used for the initial ERT at that site (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Drug protocols used to treat PDA.

Infants randomized to the conservative treatment (CT) group did not receive any initial pharmacologic treatments to close the PDA. Study randomization was blinded, but treatment allocation by the medical team was not blinded. Although this approach might have affected some of our outcome measures, we chose it because treatment blinding would have required unnecessary intravenous lines and therapy, as well as additional blood tests for infants in the CT group.

Infants in both groups had repeat echocardiogram performed at 7-10 days after randomization. Infants with a persistent moderate-to-large PDA after the first week were followed with frequent (every 7-14 days) echocardiograms to determine when ductus constriction occurred. Echocardiograms were performed until ductus closure or hospital discharge.

Infants in the CT group with a persistent moderate-to-large PDA after the first week were eligible for rescue PDA drug treatment only if they met 1 or more of the following prespecified rescue criteria: (1) inotrope-dependent hypotension that required continuous dopamine support for at least 3 days (with no obvious cause, other than the moderate PDA, to explain the condition), with hypotension defined as mean blood pressure at least 2–3 mmHg below the infant’s postmenstrual age; (2) oliguria that persisted for at least 2 days with no obvious cause, other than the moderate PDA, to explain the condition; (3) requirement for gavage feedings beyond 35 weeks postmenstrual age owing to increased work of breathing; and (4) requirement for respiratory support at the following postnatal ages when surpassing specific minimal ventilation and FiO2 requirements: >15 days if still requiring intubation and FiO2 ≤0.30, >20 days if still requiring intubation and FiO2 <0.30 or still requiring nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation and FiO2 >0.30), >30 days if still requiring nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation and FiO2 0.25-0.30, and >45 days if still requiring nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation and FiO2 <0.25 (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table I.

Rescue criteria present when infants initially qualified for having met rescue criteria

| Criteria present when infants initially met the rescue criteria* | CT group,* % | ERT group,* % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate-to-large PDA on echocardiogram, plus | 100 | 100 | ||

| Inotrope-dependent hypotension | 30 | 20 | ||

| Oliguria | 0 | 0 | ||

| Nipple feeding and work of breathing | 2 | 3 | ||

| Respiratory | 95 | 93 | ||

| Respiratory support needed | FiO2 needed | At postnatal age, d | ||

| Intubated | >0.30 | >15 | 33 | 47 |

| Intubated | ≤0.30 | >20 | 47 | 27 |

| Nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation | >0.30 | >20 | 7 | 13 |

| Nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation | 0.25-0.30 | >30 | 3 | 0 |

| Nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation | <0.25 | >45 | 5 | 6 |

Infants were not eligible for rescue treatment unless a moderate-to-large PDA was present and the need for blood pressure, renal, nipple feeding, or respiratory support surpassed the minimal criteria listed above. Sixty-two percent of the CT group and 31% of the ERT group infants met the rescue criteria during the hospitalization. Listed here are the criteria present when infants initially met the rescue criteria. Some infants met more than 1 rescue criterion (hypotension, nipple feeding, or respiratory) at the time they were judged to have met the rescue criteria.

Rescue criteria were mutually agreed on by all the study investigators. The criteria were developed from a study of 200 preterm infants (delivered at <28 weeks of gestational age) who closed their ductus during the first postnatal week. The criteria were based on the maximal amount of support that <25% of the infants with a closed ductus might still need at a particular postnatal age (unpublished results).

The rescue drug treatment for the CT group was the same drug treatment protocol used in the ERT group at that site. Neonatologists caring for infants in the CT group were not required or encouraged to treat infants who met the rescue criteria; rather, the rescue criteria served as the threshold or the minimal criteria necessary for infants in the CT group to be eligible for closure treatment. Infants in the ERT group with a persistent moderate-to-large PDA after the first week could receive rescue treatment at the clinician’s discretion irrespective of whether they met the rescue criteria.

Surgical ligation was used only if pharmacologic agents had failed or were contraindicated.24,27 The decision to use rescue ligation was left to the attending neonatologist.

A Data Safety Monitoring Board performed regular interim analyses for both safety and efficacy and reviewed all serious adverse events.

Statistical Analyses

This trial was planned as a pilot exploratory trial. The primary outcome was the need for ligation or need for PDA cardiology follow-up after discharge. We chose this outcome because we anticipated that 200 patients would provide sufficient power to detect a significant increase in the “need for ligation or the need for PDA cardiology follow-up after discharge” from an expected rate of 41% in the ERT group (based on data from University of California San Francisco, not shown) to >62% in the CT group.

One of the main goals of this small exploratory trial was to determine the incidence of serious neonatal morbidities in the 2 treatment groups so that hypotheses for future appropriately powered large-scale RCTs could be generated. In our proposal to the funding agency, we prespecified several secondary outcomes that we planned to examine and present descriptively because of the small size of the study population. These included the duration of intubation and respiratory support, need for diuretic therapy, time before full enteral intake was achieved, duration of gavage feeding, average daily weight gain, incidence of persistent moderate-to-large PDA shunt at 10 days after enrollment, incidence of rescue treatment eligibility criteria met, and incidence of serious neonatal morbidities (NEC, BPD, death, BPD/death). The incidences of several other important morbidities and therapies were also examined as additional “exploratory analyses.”

All analyses were based on the infants’ group randomization assignments. Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for all statistical analysis. The χ2 test was used to compare the treatment groups for categorical variables. For continuous variables, the Student t test was used to compare groups for parametric variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare groups for nonparametric variables. Logistic regression was used to determine the risk ratio and risk difference for the predictor variable (treatment group) and the various outcome measures. Linear regression and Poisson regression were used to determine the mean difference between the groups where appropriate. Generalized estimating equations were used to determine whether infant gestational age modified the effects of treatment assignment on the various outcomes of interest.

Despite randomization, infants in the 2 treatment groups differed in 2 of the prenatal and neonatal demographic variables: multiple birth and early-onset bacteremia (Table II). Therefore, we created additional multivariate models designed to examine the effects of treatment assignment on neonatal outcomes. The adjusted multivariate models used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering within center and included gestational age, multiple births, early-onset bacteremia, and the variable of interest (treatment assignment). An interaction term between treatment assignment and gestational age was also included in the model for a particular outcome if the interaction between treatment assignment and gestational age for that outcome reached a level of significance of P < .15.

Table II.

Baseline demographic data of the CT and ERT groups of the PDA-TOLERATE study

| Total population (n = 202) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | CT group (n = 98) | ERT group (n = 104) |

| Prenatal variables | ||

| Maternal age, y, mean ± SD | 29.9 ± 6.4 | 28.9 ± 6.3 |

| Multiple gestation, % | 39 | 25* |

| Premature rupture of membranes, % | 20 | 20 |

| Preeclampsia, % | 19 | 17 |

| Chorioamnionitis, % | 16 | 15 |

| Diabetes, % | 7.1 | 1.9† |

| Cesarian delivery, % | 70 | 68 |

| Betamethasone, % | ||

| None or <6 h | 26 | 32 |

| 6-23 h | 10 | 4 |

| 24-48 h | 13 | 12 |

| >48 h | 51 | 53 |

| Neonatal variables before enrollment | ||

| Gestational age, wk, mean ± SD | 25.9 ± 1.1 | 25.7 ± 1.2 |

| Birth weight, g, mean ± SD | 809±179 | 790±159 |

| Small for gestational age, % | 10 | 5 |

| Female sex, % | 56 | 54 |

| Caucasian, % | 55 | 49 |

| 5-min Apgar score ≥6, % | 72 | 71 |

| 10-min Apgar score ≥6, % | 93 | 92 |

| Delivery room intubation, % | 71 | 67 |

| Surfactant, % | 94 | 88 |

| Intubation at 24 h, % | 70 | 59 |

| RSS at 24 h after birth, median (IQR) | 2.10 (1.47-2.86) | 1.89 (1.47-2.70) |

| Early-onset bacteremia, % | 0 | 6.7* |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage, % | 3.1 | 4.8 |

| Dopamine, % | 35 | 34 |

| Hydrocortisone, % | 3.1 | 3.9 |

| Enrollment variables | ||

| Enrollment age, d, mean ± SD | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 8.1 ± 2.1 |

| Enrollment weight, g, mean ± SD | 799± 152 | 782±155 |

| Intubated at enrollment, % | 48 | 51 |

| RSS at enrollment, median (IQR) | 2.00 (1.46-2.75) | 1.96 (1.47-2.81) |

| Dopamine at enrollment, % | 6.1 | 6.7 |

| Maximal enteral feed before enrollment, mL/kg/d, median (IQR) | 28 (10-70) | 20 (11-50) |

RSS, Respiratory Severity Score.

P <.05.

P ≤.10.

Results

Between January 2014 and June 2017, we screened 1788 consecutively admitted infants aged 6-14 days for study entry (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com). Ten percent died before enrollment, 41% experienced spontaneous ductus constriction before the enrollment period (the incidence of spontaneous ductus constriction varied markedly among centers; Table III, available at www.jpeds.com), and 1% required insufficient respiratory support to enter the study even though they had a moderate-to-large PDA shunt. Therefore, 48% of the infants were eligible for the study. However, only 24% of eligible infants were enrolled because of concurrent exclusion criteria, parent refusal, parent or investigator unavailability, or the physician’s decision to treat or not to treat PDA outside of the study (“lack of equipoise”) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of patient entry into the study. *Percentage of eligible infants who were excluded owing to previous NEC/intestinal perforation or to dopamine-dependent hypotension, hydrocortisone-dependent hypotension, active pulmonary hemorrhage, abnormal renal function, or profound thrombocytopenia/coagulopathy at the time of enrollment. Some infants had more than 1 exclusion criterion.

Table III.

Incidence of spontaneous ductus constriction among 1788 infants of <28 weeks gestation age screened at postnatal age 6-14 days during the study enrollment period

| Center | Moderate-to-large PDA not present in infants ≤25 wk (n = 858),% | Center | Moderate-to-large PDA not present in infants ≥26 wk (n = 930),% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 8 | 16 | 21 |

| 3 | 11 | 3 | 34 |

| 17 | 11 | 15 | 35 |

| 6 | 14 | 2 | 42 |

| 9 | 14 | 5 | 44 |

| 15 | 14 | 17 | 46 |

| 7 | 15 | 7 | 54 |

| 13 | 16 | 13 | 55 |

| 2 | 20 | 9 | 56 |

| 10 | 20 | 8 | 57 |

| 5 | 21 | 10 | 58 |

| 12 | 29 | 6 | 59 |

| 11 | 34 | 12 | 60 |

| 4 | 40 | 1 | 62 |

| 14 | 43 | 4 | 62 |

| 8 | 47 | 14 | 74 |

| 1 | 50 | 11 | 78 |

| Total group | 26 | Total group | 54 |

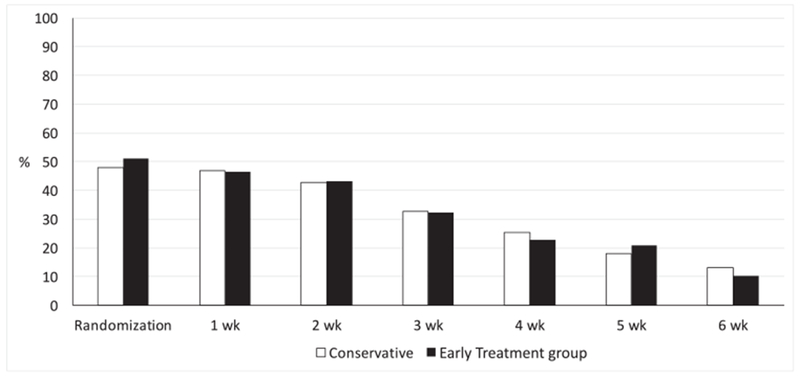

Infants in the CT and ERT groups had similar prenatal and neonatal demographic characteristics except for the incidences of multiple births and early-onset bacteremia (Table II). There was no significant difference between the groups in our primary outcome of ligation or presence of a PDA at discharge. Similarly, there was little difference between the groups in most of our prespecified secondary outcomes: duration of intubation and respiratory support, time until achievement of full enteral intake, duration of gavage feeding, and incidence of serious neonatal morbidities (NEC, BPD, death, and BPD/death) (Table IV, Figure 3, and Figure 4; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table IV.

Neonatal outcomes

| Outcomes | CT group (n = 98) | ERT group (n = 104) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Ligation or outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 39 | 32 | 0.81 (0.55-1.2) | −7 (−21 to 6) |

| PDA ligation, % | 12 | 12 | 1.00 (0.47-2.1) | 0 (−9 to 9) |

| Outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 27 | 19 | 0.72 (0.42-1.2) | −7 (−19 to 4) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| NEC, %* | 19 | 16 | 0.82 (0.44-1.5) | −3 (−14 to 7) |

| BPD, % | 53 | 49 | 0.94 (0.70-1.3) | −3 (−18 to 11) |

| BPD or death before 36 wk, % | 57 | 58 | 1.00 (0.80-1.3) | 1 (13-14) |

| Death at any time during hospitalization, % | 10 | 19§ | 1.90 (0.92-3.8) | 9 (−1 to 19) |

| PDA (moderate/large) at 10 d after randomization, %* | 80 | 41‡ | 0.51 (0.40-0.66) | −39 (−51 to −26) |

| Rescue criteria met, % | 62 | 31‡ | 0.49 (0.35-0.69) | −32 (−45 to −18) |

| Received rescue treatment, % | 48 | 18‡ | 0.38 (0.24-0.60) | −30 (−43 to 18) |

| Received furosemide ≥14 d, %* | 46 | 35§ | 0.75 (0.54-1.1) | −11 (−24 to 2) |

| Days until enteral intake 120 mL/kg/d, median (IQR)* | 12 (5-24) | 16 (7.5-23) | Mean difference, 1.4 (1.3-1.5)¶ | |

| Daily weight gain, g/kg, mean ± SD* | 22.8 ± 4.6 | 22.5 ± 4.8 | Mean difference, 0.25 (−1.1 to 1.7)¶ | |

| Days until last gavage feeding, median (IQR)* | 80 (61-97) | 76 (66-104) | Mean difference, 1.0 (1.0-1.1)¶ | |

| Other exploratory analyses | ||||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage, %* | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.94 (0.14-6.60) | 0 (−4 to 4) |

| sIVH, % | 11.2 | 18.3 | 1.10 (0.43-2.6) | 1 (−7 to 8) |

| PVL (cystic), % | 11 | 13 | 1.10 (0.52-2.3) | 1 (−8 to 10) |

| ROP (treated), % | 16 | 18 | 1.20 (0.61-2.3) | 3 (−9 to 14) |

| Pneumonia, %* | 9 | 8 | 0.84 (0.34-2.1) | −2 (−9 to 6) |

| Bacteremia, %* | 21 | 30 | 1.40 (0.86-2.3) | 8 (−4 to 20) |

| Bacteremia, CONS, %* | 4 | 4 | 0.94 (0.24-3.7) | 0 (−6 to 5) |

| Bacteremia, non-CONS, %* | 17 | 26 | 1.50 (0.87-2.6) | 9 (−3 to 20) |

| Received dopamine for ≥3 d, %* | 25 | 13.3† | 0.53 (0.29-0.98) | −12 (−23 to −1) |

| Received corticosteroids for ≥7 d, %* | 38 | 28 | 0.74 (0.49-1.1) | −10 (−23 to 3) |

| Days until discharge, median (IQR)* | 93 (73-109) | 92 (76-120) | Mean difference, 1.0 (1.0-1.2)¶ | |

CONS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment with laser or bevacizumab28; sIVH, serious intracranial hemorrhage (grade 3 or 4).29

Univariate analyses examining the effects of treatment assignment on neonatal outcomes are presented. Bacteremia refers to isolated bacteremia not associated with NEC; NEC was defined as Bell classification II or greater (including NEC treated medically or surgically and “spontaneous perforations”).30 BPD was defined using a modified room air challenge test between 360/7 and 366/7 weeks’ corrected age.31 Daily weight gain was assessed from randomization until 70 days after randomization.

Reported outcome is for the incidence or time interval that occurred after randomization.

P <.05.

P <.001.

P ≤.10.

Mean difference between groups using Poisson regression (for days until enteral feed of 120 mL/kg/d, days until last gavage feeding, and days until discharge) or linear regression (for daily weight gain).

Figure 3.

Weekly incidence of intubation and mechanical ventilation among in the CT and ERT groups after randomization.

Figure 4.

Weekly respiratory severity scores in the CT and ERT groups after randomization. The box-and-whisker diagram displays minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum values. Respiratory Severity Score: mean airway pressure × FiO2.

Although the rate of death was not significantly different between the 2 groups, the ERT group tended to have a higher incidence of death (P = .07) (Table IV). The higher incidence of death in the ERT group appeared to be due to an in crease in the incidence of death from late-onset bacteremia from organisms other than coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (Table V; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table V.

Causes of death

| Cause of death | CT group (n = 98), n (%) | ERT group (n = 104), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| BPD | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Intestinal obstruction or volvulus | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| NEC | 6 (6) | 9 (9) |

| Bacteremia, non-CONS | 2 (2) | 10 (10)† |

| All causes | 10 (10) | 20 (19)* |

CONS, coagulase-negative staphylococcus.

P ≤.10.

P <.05.

As expected, compared with the CT group, the ERT group had a significantly lower incidence of moderate-to-large PDA at 1 week after randomization (Table IV) and were exposed to a moderate-to-large PDA for a significantly shorter duration after randomization (median, 7.5 days [IQR, 3-21 days] vs 22 days [IQR, 13-43 days]) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Weekly incidence of moderate-to-large PDA shunts in the CT and ERT groups after randomization. Infants were delivered between 230/7 and 256/7 weeks (ie, <26 weeks) and between 260/7 and 276/7 weeks (ie, ≥26 weeks) gestation.

Because we randomized infants based on gestational age, we planned to perform a secondary analysis to see whether gestational age altered the effects of early treatment on any of the outcomes. The distribution of each outcome’s risk by treatment group and gestational age is shown in Table VI. Despite the fact that our study did not have sufficient statistical power to identify significant interactions between early treatment and gestational age for the study outcomes, 3 of the outcomes listed in Table VI had an interaction term that reached a level of significance of P < .15: death (Pinteraction = .07), noncoagulase-negative staphylococcal bacteremia (Pinteraction = .06), and days to achieving enteral feeding of 120 mL/kg/day (Pinteraction = .07). For these 3 outcomes, the effect of treatment on outcome was different depending on the gestational age subgroup. Infants at ≥26 weeks gestational age took significantly longer to reach 120 mL/kg/day of enteral feeding, had a significantly higher incidence of late-onset bacteremia from organisms other than coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and had a significantly higher incidence of death.

Table VI.

Neonatal outcomes in infants <26 weeks and ≥26 weeks gestation

| <26 wk (n = 106) |

≥26 wk (n = 96) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | CT group (n = 51) | ERT group (n = 55) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | CT group (n = 47) | ERT group (n = 49) | Risk ratio (95% CI) |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Ligation or outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 44 | 31 | 0.72 (0.43-1.20) | 34 | 32 | 0.93 (0.52-1.70) |

| PDA ligation, % | 18 | 15 | 0.86 (0.36-2.00) | 6.4 | 8.9 | 1.40 (0.33-5.90) |

| Outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 26 | 16 | 0.63 (0.28-1.40) | 28 | 23 | 0.82 (0.40-1.70) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| NEC, %* | 24 | 18 | 0.76 (0.36-1.60) | 13 | 13 | 0.94 (0.33-2.70) |

| BPD, % | 70 | 62 | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | 37 | 36 | 0.97 (0.56-1.70) |

| BPD or death, % | 75 | 69 | 0.93 (0.73-1.20) | 38 | 45 | 1.20 (0.72-1.90) |

| Death, % | 18 | 22 | 1.20 (0.57-2.70) | 2.1 | 16† | 7.70 (1.04-59.0) |

| PDA (moderate/large) 10 d after randomization, %* | 80 | 47* | 0.59 (0.43-0.80) | 79 | 33‡ | 0.42 (0.27-0.66) |

| Rescue criteria met, % | 80 | 40‡ | 0.50 (0.34-0.71) | 43 | 20† | 0.47(0.24-0.92) |

| Received rescue treatment, % | 63 | 23‡ | 0.36 (0.21-0.62) | 34 | 13† | 0.39(0.17-0.91) |

| Received furosemide ≥14 d, %* | 49 | 40 | 0.82 (0.53-1.30) | 43 | 29 | 0.67 (0.39-1.20) |

| Days until enteral intake 120 ml/kg/d, median (IQR)* | 20 (10-31) | 18.5 (11-31) | 0.92 (0.85-1.00)¶ | 6 (3-14) | 14† (4.5-19) | 2.30 (2.10-2.60)¶ |

| Daily weight gain, g/kg/d, mean ± SD* | 21.2 ± 4.6 | 21.4 ± 4.1 | −0.26 (−2.10 to 1.60)¶ | 24.2 ± 4.2 | 23.7 ± 5.2 | 0.59 (−1.40 to 2.60)¶ |

| Days until last gavage feeding, median (IQR)* | 88 (74-118) | 90 (74-116) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00)¶ | 65 (49-84) | 68 (57-84) | 1.20 (1.20-1.30)¶ |

| Other exploratory analyses | ||||||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage, %* | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.93 (0.06-14.4) | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.96 (0.06-14.9) |

| sIVH, % | 15.7 | 23.6 | 0.93 (0.32-2.70) | 6.4 | 12.2 | 1.4 (0.25-8.20) |

| PVL (cystic), % | 20 | 13 | 0.64 (0.26-1.50) | 2.1 | 12 | 5.8 (0.72-46.0) |

| ROP (treated), % | 30 | 24 | 0.81 (0.41-1.60) | 2.2 | 12§ | 5.5 (0.67-45.0) |

| Pneumonia, %* | 13 | 7 | 0.53 (0.16-1.70) | 4 | 8 | 1.9 (0.37-10.0) |

| Bacteremia, %* | 29 | 35 | 1.17 (0.67-2.10) | 13 | 24 | 1.9 (0.78-4.70) |

| Bacteremia, CONS, %* | 2 | 7 | 0.23 (0.03-2.01) | 6 | 0 | ** |

| Bacteremia Non-CONS, %* | 27 | 27 | 0.99 (0.53-1.90) | 6 | 24† | 3.8 (1.20-12.7) |

| Received dopamine ≥3 d, %* | 44 | 22† | 0.49 (0.26-0.90) | 6.4 | 4.3 | 0.67 (0.12-3.80) |

| Received corticosteroids ≥7 d, %* | 53 | 42 | 0.79 (0.53-1.20) | 21 | 12 | 0.58 (0.23-1.50) |

| Days until discharge, median (IQR)* | 103 (91-129) | 106 (89-127) | 0.98 (0.95-1.00)¶ | 76 (62-94) | 78 (63-97) | 1.2 (1.10-1.20)¶ |

Univariate analyses examining the effects of treatment assignment on neonatal outcomes are presented.

Reported outcome is for the incidence or time interval that occurred after randomization.

P <.05.

P <.001.

P ≤.10.

Mean difference between groups using Poisson regression (for days until enteral feed 120 mL/kg/d, days until last gavage feeding, and days until discharge) or linear regression (for daily weight gain).

Risk ratio could not be calculated because the risk for the ERT group was 0.

In addition to the prespecified primary and secondary analyses, we performed several other exploratory analyses. Among these analyses, we found a significantly lower rate of dopamine-dependent hypotension in the ERT group compared with the CT group (Tables IV and VI).

In addition to the univariate models used in Table IV, we examined the effects of treatment assignment on neonatal outcomes using multivariate models. The results of the multivariate analyses (Table VII; available at www.jpeds.com) were similar to those of the univariate analyses.

Table VII.

Neonatal outcomes: Multivariate analyses examining the effects of treatment assignment on neonatal outcomes

| Multivariable model† |

||

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Relative risk (95% CI)‡ | P value |

| Primary outcome | ||

| Ligation or cardiology follow-up | 0.73 (0.50-1.04) | .083 |

| PDA ligation | 0.94 (0.62-1.43) | .774 |

| Cardiology follow-up, outpatient | 0.62 (0.32-1.21) | 0.161 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| NEC | 0.89 (0.60-1.32) | .574 |

| BPD | 0.89 (0.60-1.33) | .582 |

| BPD or death | 0.98 (0.72-1.34) | .913 |

| Death | 1.23 (0.75-2.01) | .405 |

| Mean difference between groups (95% CI)§ | ||

| Days until enteral intake 120 mL/kg/d * | +0.85 (0.77-0.93) | <.001 |

| Days until last gavage feeding* | +0.93 (0.89-0.97) | .002 |

| Mean difference between groups (95% CI)§ | ||

| Daily weight gain, g/kg* | −0.26 (−1.95 to 1.46) | .769 |

| Other outcomes | Relative risk (95% CI)‡ | |

| PDA (moderate/large) at 10 d after randomization* | 0.53 (0.35- 0.81) | .003 |

| Rescue criteria met | 0.49 (0.32-0.76) | .001 |

| Received rescue treatment | 0.39 (0.25-0.59) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage* | 1.13 (0.10-12.9) | .916 |

| sIVH | 1.03 (0.52-2.01) | .942 |

| PVL (cystic) | 0.90 (0.48-1.70) | .744 |

| ROP (treated) | 1.03 (0.40-2.68) | .940 |

| Pneumonia* | 0.67 (0.29-1.55) | .351 |

| Bacteremia* | 1.25 (0.82-1.91) | .295 |

| Bacteremia non-CONS* | 0.88 (0.47-.64) | .677 |

| Received dopamine ≥3 d* | 0.48(0.21-1.10) | .082 |

| Received corticosteroids ≥7 d* | 0.77 (0.46-1.29) | .317 |

| Received furosemide ≥14 d* | 0.77 (0.50-1.18) | .225 |

| Mean difference between groups (95% CI)§ | ||

| Days until discharge* | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | .278 |

Reported outcome is for the incidence or time interval that occurred after randomization.

Multivariate model: generalized estimating equations were used to account for clustering within center, gestational age (<26 wk vs ≥26 wk), multiple birth, and early-onset bacteremia (see Methods). An interaction term between treatment assignment and gestational age was also included in models for the outcomes of death, bacteremia non-CONS, and days until enteral intake 120 mL/kg/day, because the interaction between treatment assignment and gestational age for these 3 outcomes reached a level of significance of P< .15.

Relative risk and 95% CI in the ERT group compared with the CT group.

Mean difference and 95% CI of Early Treatment compared with Conservative Treatment group.

We also examined the outcomes in a subset ofthe total study population composed only of infants who were intubated at the time of enrollment (Table VIII; available at www.jpeds.com). The results were similar to the results presented in Table IV.

Table VIII.

Neonatal outcomes in the subgroup of infants who were intubated at the time of enrollment and randomization

| Infants intubated at enrollment (n = 100) |

Total population (n = 202) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | CT group (n = 47) | ERT group (n = 53) | CT group (n = 98) | ERT group (n = 104) |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Ligation or outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 40 | 27 | 39 | 32 |

| PDA ligation, % | 17 | 18 | 12 | 12 |

| Outpatient PDA follow-up, % | 22 | 8† | 27 | 19 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| NEC, %* | 26 | 17 | 19 | 16 |

| BPD, % | 68 | 67 | 53 | 49 |

| BPD or death, % | 72 | 74 | 57 | 58 |

| Death, % | 17 | 23 | 10 | 19† |

| PDA (moderate/large) 10 d after randomization, %* | 85 | 44§ | 80 | 41§ |

| Rescue criteria met, % | 79 | 40§ | 62 | 31§ |

| Received rescue treatment, % | 62 | 26§ | 48 | 18§ |

| Received furosemide ≥14 d, %* | 51 | 51 | 46 | 35† |

| Days until enteral intake 120 mL/kg/d, median (IQR)* | 21 (11-33) | 21 (15-32) | 12 (5-24) | 16 (7.5-23) |

| Daily weight gain, g/kg, mean ± SD* | 20.9 ± 4.3 | 20.5 ± 4.1 | 22.8 ± 4.6 | 22.5 ± 4.8 |

| Days until last gavage feeding, median (IQR)* | 88 (74-100) | 100 (78-124) | 80 (61-97) | 76 (66-104) |

| Other outcomes | ||||

| Pulmonary hemorrhage, %* | 2.1 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| sIVH, % | 15 | 25 | 11 | 18 |

| PVL (cystic), % | 17 | 17 | 11 | 13 |

| ROP (treated), % | 30 | 24 | 16 | 18 |

| Pneumonia, %* | 11 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| Bacteremia, %* | 26 | 34 | 21 | 30 |

| Bacteremia, CONS, %* | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Bacteremia, non-CONS, %* | 21 | 28 | 17 | 26 |

| Received dopamine ≥3 d, %* | 44 | 23‡ | 25 | 13.3‡ |

| Received corticosteroids ≥7 d, %* | 53 | 47 | 38 | 28 |

| Days until discharge, median (IQR)* | 103 (92-129) | 118 (92-139) | 93 (73-109) | 92 (76-120) |

PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity requiring treatment with laser or bevacizumab28; sIVH, serious intracranial hemorrhage (grade 3 or 4).

Reported outcome is for the incidence or time interval that occurred after randomization.

P ≤.10.

P <.05.

P <.001.

Discussion

We compared early routine pharmacologic treatment for PDA with a conservative approach that treated PDA only when prespecified respiratory and hemodynamic rescue criteria were met. Infants were not enrolled until after the first week of life to allow for spontaneous PDA closure. We found no significant differences between the 2 treatment groups in either our primary outcome of ligation or presence of a PDA at discharge or our prespecified secondary outcomes (Table IV, Figure 3, and Figure 4).

Several limitations of our trial may confound the interpretation of our data, however. This was a small exploratory RCT, in which information about our secondary outcomes was gathered to generate hypotheses for appropriately powered future large-scale RCTs. Because of the study’s exploratory nature, we did not have sufficient statistical power to detect significant differences for most of our secondary outcomes. In addition, when examining the secondary outcomes, we performed multiple comparisons, which reduced our statistical power even further. Study randomization was blinded, but treatment allocation was not, which might have affected some of our outcome measures. Infants were not enrolled in the trial until the end of the first week of life; as a result, 14% of potentially eligible infants were excluded owing to the presence of ductus-related exclusion criteria (eg, need for dopamine or hydrocortisone to support blood pressure, active pulmonary hemorrhage) at the time of enrollment (Figure 2). Our trial could not address whether these infants might have benefited from earlier treatment. Similarly, 21% of eligible infants were not enrolled owing to the desire of the medical team to treat (18%) or not treat (3%) the infants outside the confines of the study (Figure 2). Although infants who were not enrolled due to physician lack of equipoise tended to need more ventilator support at the time of possible enrollment (data not shown), it is unclear whether their inclusion in the trial would have changed any of the study’s outcomes; a comparable group of infants in the TOLERATE trial who were intubated at the time of enrollment had similar results as the total study population (Table VIII). Our trial also had some of the same problems that have confounded the interpretation of previous RCTs—namely, not all infants in the ERT group experienced PDA constriction after treatment, and not all infants in the CT group had a prolonged persistent PDA shunt (Table IV and Figure 5). As in other RCTs, our study investigators felt there were certain conditions that justified rescue PDA treatment even in infants assigned to the CT group; 48% of the conservatively managed infants received rescue treatment at a median age of 12 days (IQR, 7-16 days) after randomization (Tables I and IV). The fact that early treatment drugs frequently failed to constrict the PDA and that conservatively managed infants received rescue treatment minimizes the difference in the duration of PDA exposure between the groups and biases the results toward the null hypothesis.

One of the main goals of our exploratory trial was to determine the incidence of serious neonatal morbidities (eg, BPD, NEC) in the 2 treatment groups so that hypotheses for future appropriately powered large-scale RCTs could be generated. In our study population, there were negligible differences in the incidences of BPD and NEC between the ERT and CT groups. Early treatment appeared to have no beneficial effect on the incidence of BPD in infants at ≥26 weeks of gestational age (Table VI) and only a limited effect in infants at <26 weeks of gestational age (Table VI). Our results suggest that more than 1100 infants at <26 weeks of gestational age would need to be enrolled in a similarly designed RCT to provide sufficient power to test this relationship.

Despite the relatively small number of patients enrolled in our trial, several outcomes appear to be significantly linked to early PDA treatment that merit further exploration in future trials. Infants in the ERT group had a significantly lower incidence of dopamine-dependent hypotension (Table IV); this was seen primarily in infants at <26 weeks of gestational age (Table VI). This finding is consistent with an earlier study that found a decreased incidence of inotrope-dependent hypotension when prophylactic indomethacin was started shortly after birth.18 On the other hand, early treatment appeared to increase the incidence of several serious neonatal morbidities, primarily among infants at ≥26 weeks gestational age. Early treatment was associated with delayed time to achieve enteral feeding of 120 mL/kg/day, increased incidence of late-onset bacteremia (with organisms other than coagulase-negative Staphylococcus), and increased incidence of death among infants of ≥26 weeks gestational age at birth (Table VI). The increased incidences of late-onset bacteremia and death in our ERT group were not been observed in previous RCTs8,17,19–21,23 and thus may be due to chance. However, there are important differences in study design between our trial and previous RCTs that may account for the apparent differences in infection and death rates between our ERT and CT groups. In contrast to previous RCTs, in our trial infants in the CT group were not treated with a placebo drug and did not require an intravenous catheter for placebo administration. The CT group also achieved an enteral feeding volume of 120 mL/kg/day significantly faster than the ERT group (Table VI), because they did not have enteral feeding restrictions (as can occur with indomethacin or ibuprofen treatment protocols).32,33 Although we did not record the duration of intravenous catheter use, we speculate that infants in the ERT group may have had more exposure to intravenous catheters compared with infants in the CT group, which along with the delay in enteral feeding may account for the increased incidence of bacteremia and bacteremia-related deaths. Future RCTs may need to weigh the benefits of placebo controls against these potential risks when considering placebos that require intravenous catheterization. Whatever the cause, future and ongoing RCTs will need to pay careful attention to these serious morbidities.

In conclusion, we found that compared with an approach that used PDA treatment only when prespecified rescue criteria were met, early routine PDA treatment in preterm infants <28 weeks of gestational with moderate-to-large PDA at the end of the first week did not reduce PDA ligations or presence of a PDA at discharge and did not improve any of the prespecified secondary outcomes, but delayed full feeding and may increase the risk of late-onset sepsis and death in infants ≥26 weeks of gestational age.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mark Cocalis and the cardiologists at all of the participating institutions for their expert help in reading and interpreting the echocardiograms, as well as Dr Nancy Hills of the University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute for her expert statistical consultation.

Supported by grants from the Gerber Foundation, US Public Health Service, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL109199), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR001872, UL1 TR000004, and UL1TR001873), and a gift from the Jamie and Bobby Gates Foundation.

Glossary

- BPD

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CPAP

Continuous positive nasal airway pressure

- CT

Conservative treatment

- ERT

Early routine treatment

- FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Appendix

Additional PDA-TOLERATE Investigators and Participating Sites

Study Coordinating Center:

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (n = 53)

Scott Fields, PharmD

NCRC nurses

Providence St Vincent Medical Center, Portland, OR (n = 14)

Lora Whitten, RN

Stefanie Rogers, MD

Ankara University School of Medicine Children’s Hospital, Ankara, Turkey (n = 15)

Emel Okulu, MD

Gaffari Tunc, MD

Tayfun Ucar, MD

Sisli Hamidiye Etfal Training and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Turkey (n = 14)

Ebru Türkoglu Ünal, MD

Umea University Hospital, Umea, Sweden (n = 14)

Sharp Mary Birch Hospital, San Diego, CA (n = 13)

Jane Steen, RN

Kathy Arnell, RN

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL (n = 13)

Sarah Holtschlag, RN

Michael Schreiber, MD

Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center, Santa Clara, CA (n = 13)

Morristown Medical Center, Morristown, NJ (n = 12)

Caryn Peters, RN

Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD (n = 10)

Maureen Gilmore, MD

University of Glasgow, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, UK (n = 7)

Lorna McKay, RN

Dianne Carole, RN

Annette Shaw, RN

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (n = 7)

Malinda Harris, MD

Amy Amsbaugh, RRT

Lavonne M. Liedl, RRT

Northshore University Health System, Evanston, IL (n = 6)

Sue Wolf, RN

Avi Groner, MD

University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA (n = 4)

Amy Kimball, MD

Jae Kim, MD

Renee Bridge, RN

Ellen Knodel, RN

Good Samaritan Hospital, San Jose, CA (n = 3)

Chrissy Weng, RN

South Miami Hospital/Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, FL (n = 2)

Magaly Diaz Barbosa, MD

Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY (n = 2)

Richard Polin, MD

Marilyn Weindler, RN

Data Safety Monitoring Committee:

Shahab Noori, MD, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Jeffrey Reese, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Yao Sun, MD, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, Toronto, ON, Canada, May 5-8, 2018.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

References

- 1.Koch J, Hensley G, Roy L, Brown S, Ramaciotti C, Rosenfeld CR. Prevalence of spontaneous closure of the ductus arteriosus in neonates at abirth weight of 1000 grams or less. Pediatrics 2006;117:1113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nemerofsky SL, Parravicini E, Bateman D, Kleinman C, Polin RA, Lorenz JM. The ductus arteriosus rarelyrequires treatment in infants >1000 grams. Am J Perinatol 2008;25:661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung SI, Chang YS, Chun JY, Yoon SA, Yoo HS, Ahn SY, et al. Mandatory closure versus nonintervention for patent ductus arteriosus in very preterm infants. J Pediatr 2016;177:66–71.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clyman RI, Mauray F, Heymann MA, Roman C. Cardiovascular effects of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm lambs with respiratory distress. J Pediatr 1987;111:579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimada S, Kasai T, Konishi M, Fujiwara T. Effects of patent ductus arteriosus on left ventricular output and organ blood flows in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome treated with surfactant. J Pediatr 1994;125:270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemmers PM, Molenschot MC, Evens J, Toet MC, van Bel F. Is cerebral oxygen supply compromised in preterm infants undergoing surgical closure for patent ductus arteriosus? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2010;95:F429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Faleh K, Smyth J, Roberts R, Solimano A, Asztalos E, Schmidt B. Prevention and 18-month outcomes of serious pulmonary hemorrhage in extremely low birth weight infants: results from the trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms. Pediatrics 2008;121:e233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kluckow M, Jeffery M, Gill A, Evans N. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of early treatment of the patent ductus arteriosus. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99:F99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez Fontán JJ, Clyman RI, Mauray F, Heymann MA, Roman C. Respiratory effects of a patent ductus arteriosus in premature newborn lambs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1987;63:2315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpan G, Scheerer R, Bland R, Clyman R. Patent ductus arteriosus increases lung fluid filtration in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 1991;30:616–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alpan G, Mauray F, Clyman RI. Effect of patent ductus arteriosus on water accumulation and protein permeability in the lungs of mechanically ventilated premature lambs. Pediatr Res 1989;26:570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szymankiewicz M, Hodgman JE, Siassi B, Gadzinowski J. Mechanics of breathing after surgical ligation of patent ductus arteriosus in newborns with respiratory distress syndrome. Biol Neonate 2004;85:32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCurnin D, Seidner S, Chang LY, Waleh N, Ikegami M, Petershack J, et al. Ibuprofen-induced patent ductus arteriosus closure: physiologic, histologic, and biochemical effects on the premature lung. Pediatrics 2008;121:945–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alpan G, Clyman RI. Cardiovascular effects of surfactant replacement with special reference to the patent ductus arteriosus In: Robertson B, Taeusch HW, eds. Surfactant therapy for lung disease: lung biology in health and disease. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1995, p. 531–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rakza T, Magnenant E, Klosowski S, Tourneux P, Bachiri A, Storme L. Early hemodynamic consequences of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants with intrauterine growth restriction. J Pediatr 2007;151:624–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aranda JV, Clyman R, Cox B, Van Overmeire B, Wozniak P, Sosenko I, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on intravenous ibuprofen L-lysine for the early closure of nonsymptomatic patent ductus arteriosus within 72 hours of birth in extremely low-birth-weight infants. Am J Perinatol 2009;26:235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke L, Steer P, Woodgate P. Indomethacin for asymptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD003745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liebowitz M, Koo J, Wickremasinghe A, Allen IE, Clyman RI. Effects of prophylactic indomethacin on vasopressor-dependent hypotension in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr 2017;182:21–7.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowlie PW, Davis PG, McGuire W. Prophylactic intravenous indomethacin for preventing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;7:CD000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohlsson A, Walia R, Shah SS. Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight (or both) infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2:CD003481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohlsson A, Shah SS. Ibuprofen for the prevention of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm and/or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;7:CD004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benitz WE. Treatment of persistent patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: time to accept the null hypothesis? J Perinatol 2010;30:241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sosenko IR, Fajardo MF, Claure N, Bancalari E. Timing of patent ductus arteriosus treatment and respiratory outcome in premature infants: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr 2012;160:929–35.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jhaveri N, Moon-Grady A, Clyman RI. Early surgical ligation versus a conservative approach for management of patent ductus arteriosus that fails to close after indomethacin treatment. J Pediatr 2010;157:381–7.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Hajjar M, Vaksmann G, Rakza T, Kongolo G, Storme L. Severity of the ductal shunt: a comparison of different markers. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90:F419–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Mashad AE, El-Mahdy H, El Amrousy D, Elgendy M. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety of paracetamol, ibuprofen, and indomethacin in closure of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickremasinghe AC, Rogers EE, Piecuch RE, Johnson BC, Golden S, Moon-Grady AJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes following two different treatment approaches (early ligation and selective ligation) for patent ductus arteriosus. J Pediatr 2012;161:1065–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics 2005;116:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1500 gm. J Pediatr 1978;92:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978;187:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh MC, Yao Q, Gettner P, Hale E, Collins M, Hensman A, et al. Impact of a physiologic definition on bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates. Pediatrics 2004;114:1305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clyman R, Wickremasinghe A, Jhaveri N, Hassinger DC, Attridge JT, Sanocka U, et al. Enteral feeding during indomethacin and ibuprofen treatment of a patent ductus arteriosus. J Pediatr 2013;163:406–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jhaveri N, Soll RF, Clyman RI. Feeding practices and patent ductus arteriosus ligation preferences-are they related? Am J Perinatol 2010;27:667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]