Abstract

Background

Many patients in the United States have limited or no health insurance at the time when they develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD). We examined whether health insurance limitations affected the likelihood of peritoneal dialysis (PD) use.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort analysis of patients from the US Renal Data System initiating dialysis in 2006 through 2012.

Setting & Participants

We identified socioeconomically-similar groups of patients to examine the association between health insurance and PD use. Patients aged 60-64 years with “limited insurance” (defined as having Medicaid or no insurance) at ESRD onset were compared to patients aged 66-70 years who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid at ESRD onset.

Predictor

Type of insurance coverage at ESRD onset.

Outcomes

The likelihoods of receiving PD prior to the fourth dialysis month, when all patients qualified for Medicare due to ESRD, and of switching to PD following receipt of Medicare.

Results

After adjusting for observable patient and geographic differences, patients with limited insurance had an absolute 2.4% (95% CI, 1.1%-3.7%) lower probability of PD use by their fourth dialysis month compared to patients with Medicare at ESRD onset. The association between insurance and PD use reversed once patients became Medicare eligible; patients with limited insurance had a three-fold higher rate of switching to PD between their fourth and twelfth months of dialysis (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.8-4.6) compared to patients with Medicare at ESRD onset.

Limitations

Because this study was observational, there is a potential for bias from unmeasured patient-level factors.

Conclusions

Despite Medicare’s policy of covering patients in the month that they initiate PD, insurance limitations remain a barrier to PD use for many patients. Educating providers about Medicare reimbursement policy and expanding access to pre-ESRD education and training may help to overcome these barriers.

Keywords: health insurance, health disparities, dialysis modality, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), PD use, hemodialysis (HD), renal replacement therapy (RRT), Medicare, Medicaid, insurance coverage, US Renal Data System (USRDS), Peritoneal Dialysis, Health Insurance, Health Economics

Approximately 60,000 adults under the age of 65 years in the United States develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) each year, and are treated with dialysis or kidney transplantation.1 Many of these patients are uninsured or only have state-sponsored Medicaid at the onset of ESRD.2 Although patients who are uninsured or who have Medicaid can experience limited access to healthcare,3–5 access to dialysis care is generally not a problem. Because federal law grants Medicare coverage to patients with ESRD regardless of their age, nearly all patients qualify for Medicare by their fourth month of dialysis;6 dialysis facilities generally accept patients after confirming that they will soon qualify for Medicare.

The majority of patients who require renal replacement therapy do not have a kidney donor available and therefore must initiate either in-center hemodialysis (ICHD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD). Home hemodialysis is a third option available through some centers. While evidence does not definitively indicate a survival benefit from one dialysis modality over another,7 dialysis modality can have a profound effect on a patient’s day-to-day life and satisfaction with the care received.8 For younger patients with limited health insurance, PD may be particularly attractive. Instead of traveling to a hemodialysis center three or more times per week to receive therapy, patients administer PD at home, oftentimes at night. PD is less costly than ICHD, and patients receiving PD are more likely to remain employed, perhaps due to greater flexibility over when and where to administer dialysis.9,10 Yet, only 8% of dialysis patients in the United States use PD, compared to more than 20% in many other countries.1, 11 Barriers to PD use include inadequate patient education, unfamiliarity with the therapy among some providers, and financial disincentives.12–17 Patients must also undergo surgical placement of a PD catheter before they can initiate PD, which may prove difficult in patients who are uninsured or only have Medicaid.

It is unknown whether the type of health insurance patients have at the onset of ESRD influences their likelihood of receiving PD. While patients younger than 65 years receiving ICHD must wait three months to become eligible for Medicare, patients become eligible for Medicare on the first day of the calendar month that they initiate PD. Expedited Medicare coverage for patients initiating PD could mitigate insurance-related barriers. Enactment of the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS) in 2011 created a new economic incentive for some providers to offer PD, leading to increased use of PD,18,19 and potentially mitigating insurance-related barriers. Yet, much of the decision-making and preparation for PD must occur prior to initiation of dialysis and before patients qualify for Medicare based on having ESRD. Prior to the initiation of dialysis, patients may still face insurance-related limitations in access to healthcare. In this study we examine whether health insurance coverage affects the use of PD early in dialysis, and whether the effect of health insurance coverage changed after enactment of the ESRD PPS.

METHODS

Patient Selection and Data Sources

From the US Renal Data System (USRDS) registry, we selected patients with incident ESRD who initiated ICHD or PD as their first dialysis modality in 2006 through 2012. In all analyses, we excluded patients who died, recovered kidney function, or received a kidney transplant in the first 90 days of dialysis. Information about dialysis modality is reported in the USRDS database and comes from a variety of sources, including the Medical Evidence Report (form CMS-2728), which nephrologists complete for all patients at the onset of ESRD, Medicare claims, and information collected by the ESRD Networks.

To examine the association between health insurance and PD use, we selected patients based on insurance criteria and age at dialysis initiation. We compared patients who had “limited insurance” (defined as being uninsured or having Medicaid only) to patients with Medicare at the onset of ESRD. We applied several restrictions to identify a study cohort that was as homogenous as possible. We only included patients with limited insurance who were aged 60-64 years, and who entered Medicare’s “90-day waiting period” at the onset of ESRD. Patients in the 90-day waiting period become eligible for Medicare coverage after three calendar months of ESRD. We only included patients with Medicare at the onset of ESRD who were aged 66-70 years. Selecting patients who were of similar ages minimized the magnitude of underlying health differences between the two populations; the primary difference between our comparison groups was that one group had Medicare when they developed ESRD since they were older than 65 years, while the slightly younger group with limited insurance had to wait three months after the onset of ESRD (or until intiating home dialysis) before qualifying for Medicare. We also required that patients who were 66-70 years old with Medicare also had Medicaid (“dually eligible”), to ensure that the cohort was similar socioeconomically (Item S1).

Study Exposures

The study exposure was whether patients had limited insurance (Medicaid only or uninsured) or Medicare at dialysis initiation. We used the Medical Evidence Report and Medicare enrollment data to ascertain information about patients’ insurance coverage at the dialysis initiation, and excluded instances where the two sources conflicted.

Study Outcomes

We examined the following two study outcomes: 1) receipt of PD by the start of a patient’s fourth dialysis month; and, 2) switching from ICHD to PD between the fourth dialysis month and the end of the first year of dialysis. When examining the latter outcome, we restricted our analyses to patients receiving ICHD on the first day of their fourth dialysis month. We selected these two outcomes in order to assess the potential effect of insurance coverage on PD use prior to and following the receipt of Medicare coverage at the start of the fourth dialysis month.

Covariates

Patient and dialysis facility information came from the USRDS. We obtained several patient comorbidities, frailty indicators, laboratory measurements, and body mass index (BMI), from the CMS Medical Evidence Report. In our primary analyses, we did not include pre-ESRD nephrology care as a covariate, since it may mediate the association between insurance coverage and PD use. We examined the sensitivity of our findings to this exclusion. We merged data on patients’ residential zip codes to census-based Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes and to census income data.20 Due to large population sizes, we used standardized differences to compare baseline characteristics between groups.21

Statistical Analysis and Study Design

We created two primary statistical models. The first was a multivariable logistic regression model examining the association between insurance category and PD use by the fourth dialysis month. We report odds ratios (ORs) and the predicted marginal effect of insurance category on the absolute probability of receiving PD. We also used multivariable Cox regression to examine the associations between insurance category and the rate of switching to PD. In the Cox model, we followed up patients from the fourth dialysis month through their first year after the initiation of dialysis, and censored patients if they recovered their kidney function, received a kidney transplant, or died. We used multiple imputation to account for any missing data on albumin, hemoglobin, and BMI.22 In all analyses, we adjusted for patient and geographic characteristics listed in Table 1, and the calendar year of ESRD onset represented by dummy variables. We controlled for dialysis facility characteristics when examining switches to PD, but not when examining the likelihood of receiving PD by the fourth dialysis month, since a patient may be assigned to a specific type of dialysis facility at the onset of ESRD as a consequence of his or her dialysis modality assignment.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Limited Insurance and Patients Dually Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid at Dialysis Initiation.

| Covariates | Limited Insurance* (n=8,286; age 60-64 y) | Medicare and Medicaid (n=10,060; age 66-70 y) | Absolute Std Diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||

| Received nephrology care prior to dialysis | 56.6% | 69.9% | 0.28 |

| Age (years) | 61.9 (1.4) | 68.0 (1.4) | 4.3 |

| Female sex | 52.4% | 59.4% | 0.14 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 4.7% | 6.6% | 0.08 |

| Black | 30.8% | 34.9% | 0.09 |

| Native American | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.01 |

| Other | *** | *** | *** |

| White | 62.9% | 56.9% | 0.12 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 26.2% | 22.7% | 0.08 |

| Median income (in 1,000 $) in patient zip code | 46.0 (17.1) | 45.4 (17.3) | 0.04 |

| Patient Health Characteristics | |||

| Diabetes | 66.2% | 70.0% | 0.08 |

| Coronary heart disease | 17.6% | 23.9% | 0.16 |

| Cancer | 4.3% | 5.5% | 0.06 |

| Heart failure | 32.4% | 38.5% | 0.13 |

| Lung disease | 8.2% | 12.8% | 0.15 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8.5% | 14.7% | 0.19 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11.4% | 16.6% | 0.15 |

| Smokes | 8.7% | 6.6% | 0.08 |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 2.5% | 1.7% | 0.05 |

| Immobility | 4.7% | 10.7% | 0.22 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.7 (8.0) | 29.9 (8.2) | 0.02 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.6 (1.8) | 9.9 (1.8) | 0.12 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | 0.06 |

| Dialysis Facility and Geographic Characteristics | |||

| Facility size | |||

| <50 patients | 21.3% | 19.9% | 0.04 |

| 50 - <75 patients | 19.6% | 19.8% | 0.00 |

| 75-<100 patients | 19.7% | 18.7% | 0.03 |

| ≥100 patients | 39.4% | 41.6% | 0.05 |

| For-profit | 81.7% | 83.2% | 0.04 |

| Hospital-based | 11.7% | 10.0% | 0.05 |

| Population density | |||

| Metropolitan area | 76.9% | 75.6% | 0.03 |

| Micropolitan area** | 11.5% | 12.3% | 0.02 |

| Rural area | 4.4% | 4.7% | 0.01 |

| Small town | 7.3% | 7.4% | 0.01 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as percentage; values for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation.

“Received nephrology care prior to dialysis” has 13.1% missing; “BMI” has 0.9% missing; “Hemoglobin” has 7.9% missing; “Serum albumin” has 23.0% missing. Hemoglobin and albumin documented as zero were considered missing. Maximum hemoglobin and albumin levels were 20 g/dL and 6 g/dL, respectively; minimum hemoglobin was 2 g/dL.

BMI, body mass index; Std Diff, standardized difference

Limited insurance defined as uninsured or with Medicaid and in 90-day waiting period.

Micropolitan refers to an urban area with approximately 10,000-<50,000 population.

Additional Analyses

We conducted several additional analyses. First, we examined whether observed associations between the type of insurance and PD use differed following enactment of the ESRD PPS. This was done by including in our regression models an interaction term denoting patients with limited insurance who initiated dialysis in 2011 and 2012. We used the estimates from this logistic regression analysis to plot age-stratified predicted probabilities of PD by the fourth month of dialysis. Second, we identified patients whose first dialysis modality was in-center hemodialysis and assessed whether the unadjusted (and adjusted) rates of switching to PD prior to—and following—Medicare after the 90-day waiting period varied among patients with limited insurance and Medicare (Item S2). Third, we identified patients aged 18-65 years at the onset of ESRD who entered the 90-day waiting period for Medicare coverage at dialysis initiation. We compared the likelihood of PD use by the fourth dialysis month and the rate of switching to PD after three months of dialysis among patients who were uninsured with those who only had Medicaid at dialysis initiation.

This project was approved by an Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine (ID #: H-36408). Informed consent was waived as a requirement due to a less than minimum risk to patients and the de-identified nature of the data.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Our cohort included 18,346 patients, 45% of whom had limited insurance (Medicaid or no insurance) (Figure S1). While creating our cohort, we excluded 950 patients who died in the first 90 days of dialysis. A majority of these patients (94%) had Medicare coverage at dialysis initiation. Among patients with Medicare, 4.3% used PD by the fourth month of dialysis, compared with 2.7% among patients with limited insurance (p<0.001). Patients with limited insurance were less likely to have received nephrology care prior to dialysis, were less likely to be female, and were less likely to have coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, lung disease, and immobility. They had lower serum hemoglobin and were more likely to be White (Table 1).

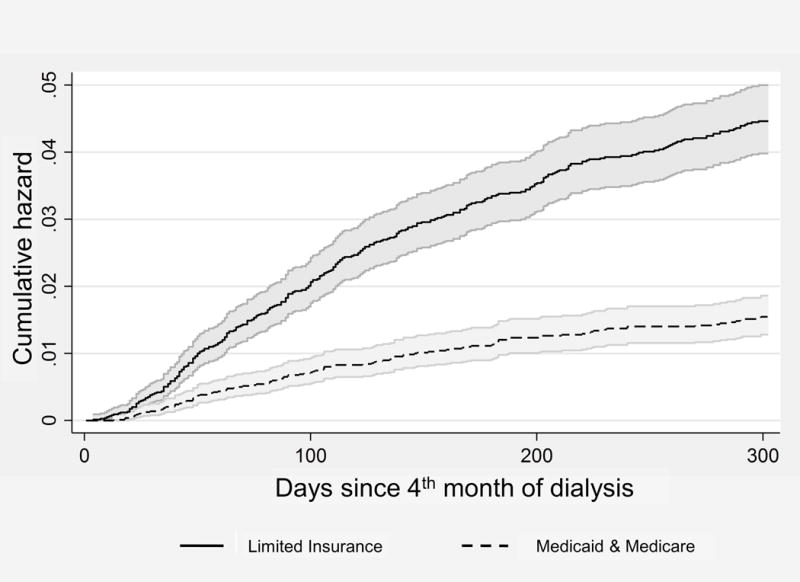

Among patients receiving ICHD at the start of their fourth dialysis month (n=17,289), 3.7% with limited insurance switched to PD over the remainder of their first year of dialysis, compared to 1.2% among patients with Medicare at dialysis initiation (p<0.001; Figure 1). Between days 90 and 365, we censored 23% and 33% of patients with limited insurance and Medicare for death, respectively. Likewise, 0.6% and 0.3% of patients with limited insurance and Medicare were censored for kidney transplantation, respectively.

Figure 1. Unadjusted Hazard of Switching to Peritoneal Dialysis among Patients Receiving Hemodialysis by the 4th Month of Dialysis.

Note: Limited Insurance includes patient who are uninsured and who have Medicaid at the onset of dialysis. Cumulative hazards calculated using the Kaplan Meier method.

Primary Regression Results

In multivariable regression analysis, patients with limited insurance at the onset of ESRD were less likely to receive PD by their fourth dialysis month compared to those with Medicare (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.33-0.71); Table 2). This translated into an average predicted decrease of 2.4% (95% CI, 1.1%-3.7%) in the absolute adjusted probability of PD use among patients with limited insurance. The magnitude of this difference was only slightly smaller after adjusting for differences in pre-ESRD nephrology care (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.35-0.76). After the third month of dialysis, when patients acquired Medicare, patients with limited insurance at ESRD onset were significantly more likely to switch to PD (hazard ratio [HR], 2.9; 95% CI, 1.8-4.6); Table S1). Our findings did not change substantively when we examined the primary logistic regression model using patients’ first dialysis modality rather than dialysis modality at the start of the fourth dialysis month (Table S2).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Results Comparing Use of Peritoneal Dialysis by 4th Month of Dialysis among Patients with Limited Insurance versus Medicare at Onset of ESRD.

| Covariates | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| overall | 0.48 (0.33-0.71) | <0.001 | |

| Year of ESRD | |||

| 2006 | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 2007 | 1.03 | [ 0.74, 1.42] | 0.9 |

| 2008 | 1.24 | [ 0.90, 1.70] | 0.2 |

| 2009 | 1.12 | [ 0.82, 1.55] | 0.5 |

| 2010 | 1.25 | [ 0.91, 1.71] | 0.2 |

| 2011 | 1.58 | [ 1.17, 2.13] | 0.003 |

| 2012 | 1.92 | [ 1.43, 2.58] | <0.001 |

| Patient Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||

| Age, per 1 -year older | 0.97 | [ 0.91, 1.02] | 0.3 |

| Female sex | 1.22 | [ 1.03, 1.44] | 0.02 |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 1.22 | [ 0.89, 1.67] | 0.2 |

| Black | 0.62 | [ 0.50, 0.76] | <0.001 |

| Native American | 0.57 | [ 0.25, 1.32] | 0.2 |

| Other | ** | ** | ** |

| White | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.93 | [ 0.75, 1.16] | 0.5 |

| Median income, per $10,000 greater | 1.02 | [ 0.97, 1.07] | 0.5 |

| Patient Health Characteristics | |||

| Diabetes | 0.81 | [ 0.68, 0.97] | 0.02 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.99 | [ 0.79, 1.22] | 0.9 |

| Cancer | 0.74 | [ 0.49, 1.12] | 0.2 |

| Heart failure | 0.72 | [ 0.60, 0.88] | <0.001 |

| Lung disease | 0.76 | [ 0.56, 1.03] | 0.07 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.83 | [ 0.63, 1.10] | 0.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.04 | [ 0.80, 1.35] | 0.8 |

| Smokes | 0.99 | [ 0.71, 1.37] | 0.9 |

| Drug or alcohol abuse | 0.68 | [ 0.31, 1.46] | 0.3 |

| Immobility | 0.26 | [ 0.15, 0.46] | <0.001 |

| BMI category | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 0.88 | [ 0.71, 1.08] | 0.2 |

| 25-<30 kg/m2 | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 30-<35 kg/m2 | 1.05 | [ 0.84, 1.32] | 0.6 |

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 0.73 | [ 0.57, 0.93] | 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin category | |||

| < 8 g/dL | 0.40 | [ 0.28, 0.57] | <0.001 |

| 8-<9 g/dL | 0.55 | [ 0.43, 0.72] | <0.001 |

| 9-<11 g/dL | 0.66 | [ 0.54, 0.79] | <0.001 |

| ≥11 g/dL | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Serum albumin category | |||

| <2 g/dL | 0.25 | [ 0.12, 0.49] | <0.001 |

| 2-<3 g/dL | 0.38 | [ 0.30, 0.48] | <0.001 |

| 3-<3.5 g/dL | 0.63 | [ 0.52, 0.77] | <0.001 |

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Geographic Characteristics : Population Density | |||

| Metropolitan | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Micropolitan* | 1.24 | [ 0.97, 1.58] | 0.09 |

| Rural area | 1.85 | [ 1.32, 2.57] | <0.001 |

| Small town | 1.24 | [ 0.90, 1.69] | 0.2 |

Note: Limited insurance group are patients with age 60-64, uninsured or with Medicaid and in 90-day waiting period and the control group are patients aged 66-70 with Medicare and Medicaid. Regression also controlled for the week of the month (measured in 7-day intervals) when patients initiated dialysis (estimates not shown).

Estimates for “other” race are omitted due to small numbers of patients.

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval: OR, odds ratio

Micropolitan refers to to an urban area with approximately 10,000-<50,000 population.

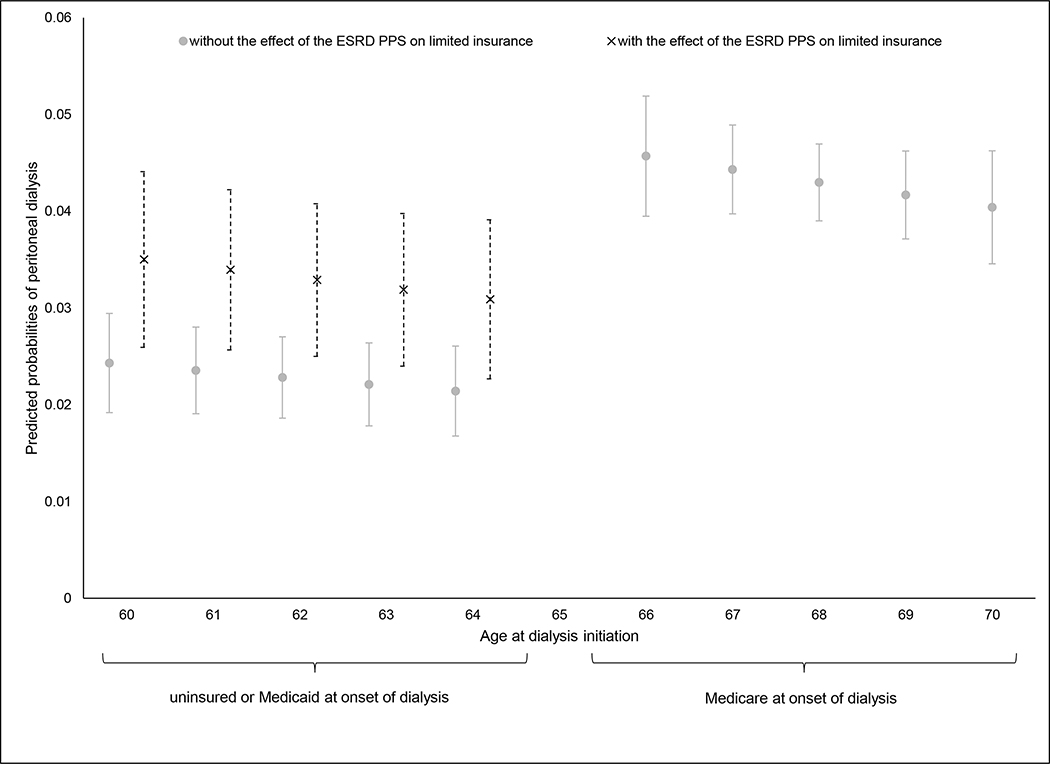

Impact of PPS on Early PD Use

A regression analysis that included post-PPS interactions estimated that, prior to enactment of the PPS, the odds of PD use by the fourth dialysis month were 58% (95% CI, 37%-72%) lower among patients with limited insurance compared to those with Medicare at dialysis initiation. The magnitude of reduction in odds became less pronounced (38%; 95% CI, 4%-60%) in the period following the PPS (p for interaction = 0.03; Table S3; Figure 2). There was no change in the relative rates of switching to PD by insurance category after the third dialysis month following enactment of the PPS (p for interaction=0.9; Table S4).

Figure 2. Age-Stratified Predicted Probabilities of Peritoneal Dialysis by the 4th Dialysis Month before versus after Enactment of the ESRD Prospective Payment System.

Note: Patients aged 60 to 64 years have Limited Insurance (i.e. are uninsured or have Medicaid-only) at dialysis initiation, while patients aged 66 to 70 years have Medicare at dialysis initiation. Predicted probabilities are derived from our logistic model estimates in a model that allowed for the effect of insurance to vary following enactment of ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS). Predicted probabilities of peritoneal dialysis use among patients with Limited Insurance are plotted both before and after the PPS. Standard errors are obtained using the delta method. Residual confounding by age may exist as a result of non-overlap of age groups by design. This residual confounding is most likely to induce a bias towards the null, thus leading to an underestimation of true effect.

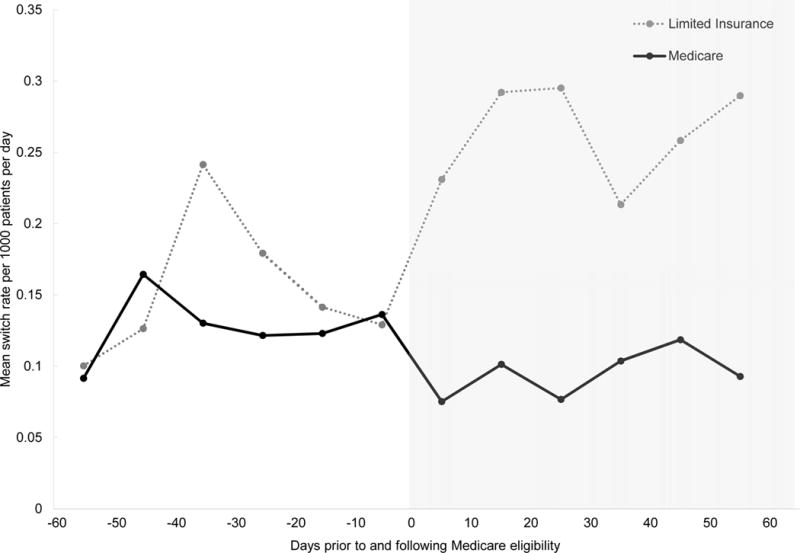

Insurance Type and Patterns of Switching to PD

When examining changes in patterns of switching to PD throughout the entire study period, we found that patients with limited insurance had a 62% increase in the unadjusted rate of switching to PD after gaining Medicare coverage (p=0.001), while patients with Medicare at dialysis initiation had a 31% non-statistically significant decrease in the rate of switching (p=0.2) (Table S5; Figure 3). We observed similar differences in changes in the rates of switching to PD among patients with limited insurance versus Medicare after the third dialysis month in a multivariable Cox regression analysis where we controlled for patient and geographic characteristics (Item S2; Table S6).

Figure 3. Unadjusted Rate of Switching to Peritoneal Dialysis before and after Medicare Eligibility based on the 90-day Waiting Period among Patients with Limited Insurance and Medicare at the onset of End-Stage Renal Disease.

Note: This figure illustrates daily rates of switching to peritoneal dialysis averaged over 10-day intervals. The shaded area represents time after patients would be eligible for Medicare based on the 90-day waiting period. For a more detailed description of how these rates were obtained, see Item S2.

Early PD Use Among Adults With Medicaid or No Health Insurance

In analyses where we compared all adults aged 18-65 initiating dialysis who were uninsured to those with Medicaid, there was no significant association between insurance category and the adjusted odds of receiving PD by the fourth dialysis month. Uninsured patients were more likely than patients with Medicaid-only to switch to PD during the remainder of their first year of dialysis after patients attained Medicare coverage based on Medicare’s 90-day waiting period (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.25-1.48; Tables S7-S9; Figure S2).

DISCUSSION

In this study of US patients initiating treatment for ESRD we observed a strong association between patients’ health insurance status and whether or not they received PD. Patients who were uninsured or who only had Medicaid prior to ESRD were approximately one-half as likely to use PD by their fourth month of dialysis as otherwise similar patients with Medicare coverage at the onset of ESRD. After three months of dialysis, when patients acquired Medicare coverage on the basis of having had ESRD for three months, the association between health insurance and home dialysis use reversed—the rate of switching from ICHD to PD over the remainder of the first year of dialysis was three-fold greater among patients with limited insurance compared to similar patients already covered by Medicare at ESRD onset. Similarly, uninsured patients were 36% more likely to switch to PD after becoming eligible for Medicare than patients with Medicaid at the onset of ESRD.

Enactment of the ESRD PPS in 2011 created new economic incentives for some providers to offer PD, leading to an overall increase in PD use throughout the United States.18 We found that this coincided with a slightly attenuated reduction in the likelihood of receiving PD by the fourth month of dialysis among patients with limited insurance compared to those with Medicare at dialysis initiation. However, significant barriers to PD persist; in the two years following the PPS, patients with limited insurance were still nearly 40% less likely to use PD by their fourth dialysis month than those with Medicare at dialysis initiation. These findings indicate that, even following enactment of the ESRD PPS, health insurance limitations are a barrier to initiating PD, and that providers may be waiting until patients attain Medicare coverage after their third dialysis month before initiating PD.

It is somewhat surprising that health insurance appeared to have such a prominent role in dialysis modality assignment. Unlike patients receiving ICHD, patients without Medicare at the onset of ESRD who receive PD do not have to wait three months to become eligible for Medicare—they acquire Medicare eligibility on the first day of the calendar month that the PD catheter is flushed.23 If a patient is a good candidate for PD, dialysis providers would have an economic incentive to initiate PD as soon as possible in order to begin receiving Medicare’s more generous reimbursement rates. Our analysis suggests that, in many instances, providers are not taking advantage of this benefit, and that patients may be unnecessarily waiting until their fourth month of dialysis before initiating PD.

Our study suggests that efforts to educate hospitals, physicians, and their administrative staff about Medicare policy—notably that Medicare covers costs incurred during the calendar month that a patient begins home dialysis—could eliminate some barriers that patients face and improve patients’ access to earlier PD care. It will be important to understand exactly where patients face the largest obstacles in order to focus educational efforts. The solution might be as simple as educating the administrative personnel in surgery offices about the opportunity for their practice to be reimbursed at Medicare’s rates for evaluating and operating on patients who will be initiated on PD later that month. It is important to note, however, that this study focuses only on one potential barrier to PD. There may other important barriers to home dialysis use, including barriers associated with government regulation and reimbursement policy, limited home support for patients, limited access to equipment and supplies, and business practices that are not conducive to offering PD.17 Medicare’s current policy for physician reimbursement in dialysis may further deter the use of home dialysis.16 Despite recent reimbursement increases,24, 25 insufficient reimbursement by Medicare for home dialysis training may limit the use of PD.

One possible explanation for the increased likelihood of switching to PD after the third month of dialysis involves the time that it takes for some patients to prepare for PD. Patients who present to the hospital with acute complications related to kidney failure (such as fluid overload or uremia) must be medically stabilized, assigned to an outpatient dialysis center, and educated about PD. Then, they must undergo surgical evaluation and placement of a PD catheter followed by training before initiating PD. In some instances this process may take more than three months. However, if increases in switching to PD after three months were due to timing, one would expect for switch rates to increase smoothly over time in all insurance groups. In contrast, we found that the rate of switching to PD did not change significantly over time among patients with Medicare. Relative to patients with Medicare, there was a sustained increase in the rate of switching to PD beginning in the fourth dialysis month among patients with limited insurance (Figure 2; Table S9).

Patients with limited health insurance may be less likely to receive PD near the initiation of dialysis due to difficulties accessing healthcare prior to the onset of ESRD. Patients who are uninsured are less likely to receive timely pre-ESRD nephrology care,5 while our data indicates that 3% fewer patients with Medicaid at the onset of ESRD received pre-ESRD nephrology care compared to those with Medicare. Many patients receiving dialysis in the United States report never having been told about a home dialysis option prior to initating dialysis.26, 27 To the extent that patients with limited insurance did not see nephrologists before initiating dialysis, they would not have had an opportunity to discuss PD. However, our findings suggest that significant insurance-related barriers to PD exist apart from whether or not a patient saw a nephrologist. Controlling for the receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care had a negligible effect on the increase in PD use by the fourth dialysis month among patients with Medicare compared to those with limited insurance.

Initiating a patient on PD requires close collaboration between nephrologists, primary care physicians, hospitals, dialysis facilities, and surgeons. Limited access or low quality of care involving any of these providers could create significant barriers to PD use. For example, decreased knowledge or experience with PD can make nephrologists hesitant to initiate PD,28 and evidence from various healthcare settings suggests that patients with limited or no health insurance receive lower quality care.29–31 It is possible that nephrologists who care for underserved populations are less likely to discuss PD with their patients. Alternatively, patients with limited insurance may experience difficulty accessing surgical and hospital services, even if they are followed up by a nephrologist. Efforts and policies to expand outreach and to educate patients about home dialysis options could remove these barriers. Some have proposed more widespread availability of urgent-start PD as another way to provide patients with access to PD.32

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, because this was an observational study, there is a possibility of selection bias if unobserved differences in patient characteristics influence decisions about dialysis modality and insurance status. It is uncertain how this potential source of bias might influence our findings. Even after excluding patients who died within 90 days of initiating dialysis, patients with Medicare at dialysis initiation appeared sicker than those with limited insurance. If we could not observe the full extent of the increased acuity of illness among the Medicare population, this difference would likely bias our findings towards the null hypothesis. In contrast, although we selected comparison groups that were similar socioeconomically, it is possible that patients with Medicare had more resources at their disposal, facilitating their abilities to administer PD at home. If our regression adjustments did not fully account for differences in resources and social support, then our findings could be biased towards identifying an association between health insurance on dialysis modality. Second, because we were examining patients without health insurance and with Medicaid-only, we were only able to use the Medical Evidence Report to ascertain patient co-morbidities, which has limitations.33, 34

In summary we found evidence that the use of PD early in dialysis can be limited by the insurance coverage that patients have when initiating dialysis. Programs designed to educate physicians, patients, and other healthcare providers about home dialysis, and policies directed toward increasing patients’ access to providers involved in preparing patients for PD, may give more patients the option to initiate PD as their first kidney replacement modality.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Diagram of cohort selection.

Figure S2: Unadjusted hazard of switching to PD among patients receiving ICHD on first day of their fourth month of ESRD.

Item S1: Overview of US Insurance for kidney disease care.

Item S2: Examining changes in PD switches after Medicare eligibility.

Table S1: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis in patients with limited insurance vs Medicare.

Table S2: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD at dialysis initiation among patients with limited insurance and Medicare.

Table S3: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD by fourth month before vs after enactment of ESRD PPS.

Table S4: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis before and after enactment of ESRD PPS.

Table S5: Unadjusted rates of switching to PD before and after Medicare eligibility based on 90-d waiting period.

Table S6: Differences-in-differences Cox model comparing changes in PD switch rates after fourth month of dialysis in patients with limited insurance vs Medicare.

Table S7: Baseline characteristics of patients without insurance and with Medicaid-only insurance.

Table S8: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD by fourth month of dialysis among patients who are uninsured vs those with Medicaid.

Table S9: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis in patients who are uninsured vs those with Medicaid.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by grant 1K23DK101693-01 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) to Dr. Erickson. Dr. Winkelmayer receives research and salary support through the endowed Gordon A. Cain Chair in Nephrology at Baylor College of Medicine. This work was also supported by the use of facilities and resources of the Houston VA Health Services Research and Development Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13-413). The funders of this study had no role in the design, collection of data, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors’ Contributions: Research idea and study design: JJP, BZ, SQ, WCW, KFE; data acquisition: WCW, KFE; data analysis/interpretation: JJP, BZ, SQ, WCW, KFE; statistical analysis: BZ, KFE; supervision or mentorship: WCW, KFE. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Disclaimer: This work was conducted under a data use agreement between Dr. Winkelmayer and the NIDDK. An NIDDK officer reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission. The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government or Baylor College of Medicine.

Peer Review: Received January 25, 2017. Evaluated by two external peer reviewers and an external methods reviewer, with editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form September 30, 2017.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, editor. United States Renal Data System. 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurella-Tamura M, Goldstein BA, Hall YN, Mitani AA, Winkelmayer WC. State medicaid coverage, ESRD incidence, and access to care. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1321–1329. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook NL, Hicks LS, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, Guadagnoli E, Landon BE. Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2007;26:1459–1468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H, et al. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. JAMA. 294:1248–1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillespie BW, Morgenstern H, Hedgeman E, et al. Nephrology care prior to end-stage renal disease and outcomes among new ESRD patients in the USA. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:772–780. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Law 92-603. §299I, codified at 42 U.S.C. §1395rr. Social Security Amendments of 1972. 1972

- 7.Chiu YW, Jiwakanon S, Lukowsky L, Duong U, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Mehrotra R. An update on the comparisons of mortality outcomes of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin HR, Fink NE, Plantinga LC, Sadler JH, Kliger AS, Powe NR. Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA. 2004;291:697–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger A, Edelsberg J, Inglese GW, Bhattacharyya SK, Oster G. Cost comparison of peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis in end-stage renal disease. American Journal of Managed Care. 2009;15:509–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muehrer RJ, Schatell D, Witten B, Gangnon R, Becker BN, Hofmann RM. Factors affecting employment at initiation of dialysis. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 6:489–496. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02550310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkie M. Home dialysis-an international perspective. NDT plus. 2011;4:iii4–iii6. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin K, Manns B, Mortis G, Hons R, Taub K. Why patients with ESRD do not select self-care dialysis as a treatment option. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2003;41:380–385. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrotra R, Blake P, Berman N, Nolph KD. An analysis of dialysis training in the United States and Canada. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2002;40:152–160. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Congress, editor. United States Government Accountability Office. End-Stage Renal Disease: Medicare Payment Refinements Could Promote Increased Use of Home Dialysis. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Effects of physician payment reform on provision of home dialysis. The American journal of managed care. 2016;22:e215–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golper TA, Saxena AB, Piraino B, et al. Systematic barriers to the effective delivery of home dialysis in the United States: a report from the Public Policy/Advocacy Committee of the North American Chapter of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58:879–885. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin E, Cheng XS, Chin KK, et al. Home Dialysis in the Prospective Payment System Era. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(10):2993–3004. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golper TA. The possible impact of the US prospective payment system (“bundle”) on the growth of peritoneal dialysis. Peritoneal dialysis international : journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 2013;33:596–599. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2013.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WWAMI. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montez-Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC, Desai M. Addressing Missing Data in Clinical Studies of Kidney Diseases. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014;9(7):1328–35. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10141013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Coordination of Benefits & Recovery Overview: End-Stage Renal Disease. Vol. 2016. Baltimore, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medicare Program. US Department of Health and Human Services, editor. End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 752010:49030–49214. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medicare Program; Services US Department of Health and Human Services. End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System, Quality Incentive Program, and Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics, and Supplies: Final Rule. 2013:72155–72253. 78 FR 72155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrotra R, Marsh D, Vonesh E, Peters V, Nissenson A. Patient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2005;68:378–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Wasse H. Patient awareness and initiation of peritoneal dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:119–124. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhary K. Peritoneal Dialysis Drop-out: Causes and Prevention Strategies. International journal of nephrology. 2011:434608. doi: 10.4061/2011/434608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvin JE, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Insurance coverage and care of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:739–748. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan O, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. Journal of hospital medicine. 2010;5:452–459. doi: 10.1002/jhm.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDavid K, Tucker TC, Sloggett A, Coleman MP. Cancer survival in Kentucky and health insurance coverage. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2135–2144. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arramreddy R, Zheng S, Saxena AB, Liebman SE, Wong L. Urgent-start peritoneal dialysis: a chance for a new beginning. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014;63:390–395. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Shaughnessy MM, Erickson KF. Measuring comorbidity in patients receiving dialysis: can we do better? American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015;66:731–734. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnan M, Weinhandl ED, Jackson S, Gilbertson DT, Lacson E., Jr Comorbidity ascertainment from the ESRD Medical Evidence Report and Medicare claims around dialysis initiation: a comparison using US Renal Data System data. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2015;66:802–812. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Diagram of cohort selection.

Figure S2: Unadjusted hazard of switching to PD among patients receiving ICHD on first day of their fourth month of ESRD.

Item S1: Overview of US Insurance for kidney disease care.

Item S2: Examining changes in PD switches after Medicare eligibility.

Table S1: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis in patients with limited insurance vs Medicare.

Table S2: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD at dialysis initiation among patients with limited insurance and Medicare.

Table S3: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD by fourth month before vs after enactment of ESRD PPS.

Table S4: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis before and after enactment of ESRD PPS.

Table S5: Unadjusted rates of switching to PD before and after Medicare eligibility based on 90-d waiting period.

Table S6: Differences-in-differences Cox model comparing changes in PD switch rates after fourth month of dialysis in patients with limited insurance vs Medicare.

Table S7: Baseline characteristics of patients without insurance and with Medicaid-only insurance.

Table S8: Logistic regression results comparing use of PD by fourth month of dialysis among patients who are uninsured vs those with Medicaid.

Table S9: Cox model comparing PD switch rates beginning at fourth month of dialysis in patients who are uninsured vs those with Medicaid.