Abstract

Alcohol is the most widely used substance of abuse among youths in Nigeria. Underage drinking poses a serious public health problem in most colleges and despite the health and safety risk, consumption of alcohol is rising. Having recourse to the public health objective on alcohol by the World Health organization, which is to reduce the health burden caused by the harmful use of alcohol, thereby saving live and reducing injuries, this data article explored the nature of alcohol use among college students, binge drinking and the consequences of alcohol consumption. Secondary school students are in a transition developmentally and this comes with its debilitating effects such as risky alcohol use which affects their health and educational attainment [1], [2]. This data article consists of data obtained from 809 (ages 14–20 years) participants from selected schools in Ota, near Lagos State, Nigeria. For data collection, the youth questionnaire on underage drinking was employed. This data article presents information on participants' alcohol demographics. Analyses of the data can provide insights into heavy episodic drinking (HED), ever drinkers, prevalence of alcohol consumption, strategies to reducing alcohol use, reasons for underage drinking and effects of alcohol consumption. The data will be useful for public health interventions.

Keywords: Alcohol, College, Underage drinking, Youths, Nigeria

Specifications Table

| Subject area | Psychology |

|---|---|

| More specific subject area | Counselling Psychology, Health Psychology |

| Type of data | Tables |

| How data was acquired | Use of questionnaire for data collection |

| Data format | Raw and analyzed (descriptive statistics) |

| Experimental factors | Cross sectional research design using the youth questionnaire on underage drinking |

| Data source location | Surveys were conducted among college students in Ota, Nigeria |

| Data accessibility | Data is included in this article |

| Related research article | Adekeye OA, Adeusi SO, Chenube OO, Ahmadu FO, Sholarin MA. Assessment of Alcohol and Substance Use among Undergraduates in Selected Private Universities in Southwest Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) 2015 20(3): 1–7. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/pages/20%283%29Version-2.html. |

Value of the Data

|

1. Data

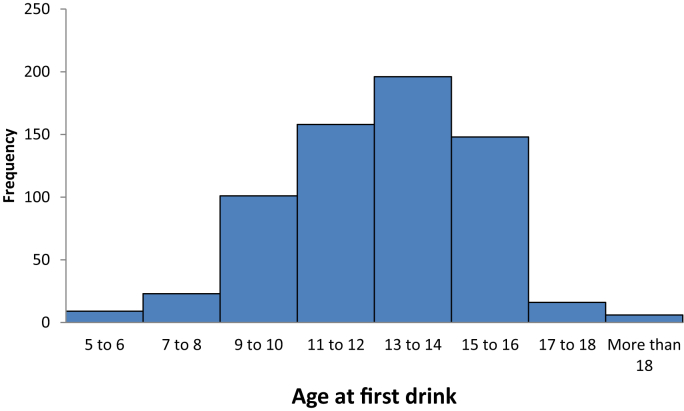

Of the 809 students surveyed, 657 (81.2%) reported having drank alcohol. About half of the students (330 [50.2%]) had their first drink between ages 14 and 17 while 253 (39%) had their first drink between ages 10 and 13 years (see Fig. 1). Comparatively, in the United States, by age 15, 33% of teens have had at least 1 drink and about 60% of teens by age 18 have had at least 1 drink [3], [4]. 54 of the respondents reported to having more than five drinks in a single drinking episode, with 34 of these respondents saying they had done so within the last month. Data on the frequency of alcohol consumption show that 154 respondents drink at least once a week, 427 consume alcohol at least once a month while 76 respondents drink alcohol more than once a month (Table 1). Five cross tabulations were presented on gender and age responses to items on ever drank alcohol, frequency of drinks, problem of alcohol consumption, participant's perception on drinking and driving and whether alcohol consumption has increased, decreased or remained at the same level of consumption. The analyses are in Table 2a–e.

Fig. 1.

The histogram showing age at first drink.

Table 1.

Frequency of alcohol consumption.

| Frequency of drink | At least once a week | At least once a month | More than once a month |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 154 | 427 | 76 |

Table 2.

a) Crosstabulation of ever drank alcohol by gender and age of respondents. b) Crosstabulation of alcohol consumption by gender and age of respondents. c) Crosstabulation of gender and age responses on problem of alcohol consumption. d) Crosstabulation of gender and age responses on problem of drinking and driving. e) Crosstabulation of gender and age responses on prevalence of alcohol consumption.

| Ever Drank |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender | Male | 438 | 115 | 553 |

| Female | 219 | 37 | 256 | |

| Total | 657 | 152 | 809 | |

| Age Group | 14years | 73 | 31 | 104 |

| 15–17years | 497 | 71 | 568 | |

| 18–20years | 87 | 50 | 137 | |

| Total | 657 | 152 | 809 | |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption n = 657 |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Once a Week | Once a Month | More than once a Month | |||

| Gender | Male | 99 | 287 | 52 | 438 |

| Female | 55 | 140 | 24 | 219 | |

| Total | 154 | 427 | 76 | 657 | |

| Age Group | 14years | 36 | 34 | 3 | 73 |

| 15–17years | 93 | 348 | 56 | 497 | |

| 18–20years | 25 | 45 | 17 | 87 | |

| Total | 154 | 427 | 76 | 657 | |

| Alcohol consumption is … n = 754 |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious problem | Not a problem | Minor problem | |||

| Gender | Male | 447 | 34 | 29 | 510 |

| Female | 192 | 20 | 32 | 244 | |

| Total | 639 | 54 | 61 | 754 | |

| Age Group | 14years | 72 | 10 | 8 | 90 |

| 15–17years | 491 | 21 | 24 | 536 | |

| 18–20years | 76 | 23 | 29 | 128 | |

| Total | 639 | 54 | 61 | 754 | |

| Drinking and driving n = 755 |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious problem | Not a problem | Minor problem | |||

| Gender | Male | 450 | 27 | 36 | 513 |

| Female | 199 | 16 | 27 | 242 | |

| Total | 649 | 43 | 63 | 755 | |

| Age Group | 14years | 72 | 7 | 12 | 91 |

| 15–17years | 485 | 24 | 31 | 540 | |

| 18–20years | 92 | 12 | 20 | 124 | |

| Total | 649 | 43 | 63 | 755 | |

| Prevalence alcohol consumption is … n = 729 |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | Decreased | Stayed the same | |||

| Gender | Male | 341 | 119 | 34 | 494 |

| Female | 180 | 35 | 20 | 235 | |

| Total | 521 | 154 | 54 | 729 | |

| Age Group | 14years | 53 | 23 | 14 | 90 |

| 15–17years | 402 | 101 | 23 | 526 | |

| 18–20years | 66 | 30 | 17 | 113 | |

| Total | 521 | 154 | 54 | 729 | |

Respondents were given some potential strategies for reducing underage drinking and were asked to pick which of the strategies or approaches they would support in the quest to decreasing alcohol use by the underage. Table 3 provides a summary of their responses [1], [5]. We also asked respondents about what they thought some of the negative consequences of alcohol consumption were and the most common answers were “been driven by drunk driver”, “being absent from school”, and “been drunk at a party” (Table 4). Our data revealed that the majority of students obtained alcohol from bars or restaurants (Table 5) and in Table 6, the most common answer they gave for why they drank alcohol was “it enables them to enjoy a party” [3], [6], [7].

Table 3.

Strategies to reducing alcohol consumption.

| Approaches to decreasing alcohol use | Frequency/(%) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol educational interventions in schools | 588 (72.7%) | 1st |

| Use of mass media to advance Alcohol education | 541 (66.9%) | 2nd |

| Ban on alcohol advertising | 490 (60.6%) | 3rd |

| Improved law enforcement | 402 (49.7%) | 4th |

| Lectures by rehabilitated Alcohol users | 384 (47.5%) | 5th |

| More punishment | 247 (30.5%) | 6th |

| Suspending driving permit/license of drunk drivers | 235 (29.0%) | 7th |

| Alcohol-free recreational centres | 200 (24.7%) | 8th |

Table 4.

Negative Consequences of Alcohol consumption.

| Negative Consequences | Frequency/(%) |

|---|---|

| Been driven by drunk driver | 104 (24.4%) |

| Been absent from school | 97 (22.7%) |

| Been drunk at party | 86 (20.0%) |

| Been drunk at school | 28 (6.6%) |

| Driving after drinking alcohol | 27 (6.3%) |

| Had an injury | 26 (6.0%) |

| Performing poorly in school | 21 (5.0%) |

| Having family problems | 21 (5.0%) |

| Been arrested | 17 (4.0%) |

Table 5.

Places where Youths obtain Alcohol.

| Where alcohol is obtained from… | Frequency/(%) |

|---|---|

| Bar/restaurant | 322 (39.8%) |

| Liquor store | 175 (21.6%) |

| Friends/relatives | 169 (20.9%) |

| Parent's home | 107 (13.2%) |

| Supermarket/convenience store | 16 (2.0%) |

| Others | 20 (2.5%) |

| Total | 809 (100.0%) |

Table 6.

Reasons for youths alcohol consumption.

| Youths drink because | Frequency/(%) |

|---|---|

| It enables them enjoy a party | 525 (26.0%) |

| Peer influence and acceptance | 485 (24.2%) |

| Relieves depression | 478 (23.8%) |

| Boredom | 318 (16.0%) |

| They want to stand up to authorities including parents | 197 (10.0%) |

2. Experimental design, materials and methods

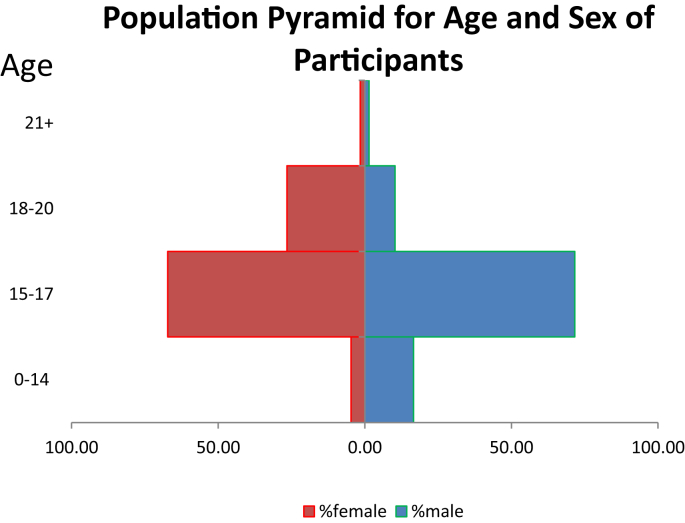

We used a cross-sectional survey for this study on adolescent drinking in Nigeria. This dataset involved 809 students from some selected senior secondary schools in Ota, a sub-urban location in Southwest, Nigeria. Fig. 2 shows the age breakdown of participants by gender. This was represented by a population pyramid. Participants were selected from across all core subject areas such as sciences, arts and humanities and business classes through stratified and simple random sampling, to cater for variables such as gender, age, living location, subject area and ethnicity. Indeed, of the 809 students surveyed, 618 were Yoruba, 142 were Igbo, and 16 were Hausa (the remaining 33 students reported their ethnicity as “other”). The inclusion criteria included that the school principal/parents must sign a consent form or provide assent in writing; the participant (student) must be in senior secondary school class, and agree to participate freely. A participant must also be at least 14 years of age and not more than 20 years. Those who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the current study. The students were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The questionnaire forms were filled in the classes with no interactions allowed among the participants and no access to the filled questionnaire forms by the school administrators. For data collection, an adapted questionnaire on youth alcohol consumption was employed. This questionnaire had items on use of alcohol and perception of youths to underage drinking and it elicited the desired information from the participants. The first part of the questionnaire dealt with respondents socio-demographic details. In order to ensure the psychometric requirements of the scale as advocated by Ref. [8], the reliability of the instrument was established using a test-retest reliability method. It was administered to 30 secondary school students and a second administration after a three-week interval with a Cronbach's Alpha of 0.83. The research trajectory was therefore considered adequate for data gathering purposes. All statistical analyses were performed using excel and IBM SPSS statistical software (v. 22).

Fig. 2.

Population pyramid showing age of participants by gender.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the management of Covenant University for providing full financial grant for this research work through the Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Discovery (CUCRID).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.103930.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.103930.

Transparency document

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Adekeye O.A. Knowledge level and attitude of school going male adolescents towards drug use and abuse. Kotangora J. Edu. 2012;12:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loukas A., Cance J.D., Batanova M. Trajectories of school connectedness across the middle school years: examining the roles of adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems. Youth Soc. 2016;48(4):557–567. https://sites.edb.utexas.edu/drrl/publications/trajectories-of-school-connectedness-across-the-middle-school-years-examining-the-roles-of-adolescents-internalizing-and-externalizing-problems/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adekeye O.A., Adeusi S.O., Chenube O.O., Ahmadu F.O., Sholarin M.A. Assessment of alcohol and substance use among undergraduates in selected private universities in Southwest Nigeria. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015;20(3):1–7. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/pages/20%283%29Version-2.html [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2015. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm#tab2-19b 2016. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman L., Cater S. 2009. Underage ‘binge’ Drinking: A Qualitative Study into Motivations and Outcomes; pp. 125–136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adekeye O.A., Odukoya J.D., Chenube O.O., Igbokwe D.O., Igbinoba A., Olowookere E.I. Subjective experiences and meaning associated with drug use and addiction: a mixed method approach. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2017;9(8):57–65. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v9n8p57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obot I.S. The measurement of drinking patterns and alcohol problems in Nigeria. J. Subst. Abus. 2000;12:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odukoya J.A., Adekeye O.A., Igbinoba A.O., Afolabi A. Item analysis of university-wide multiple choice objective examinations: the experience of a Nigerian private university. quality and quantity. Int. J. Methodol. 2018;52(3):983–997. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0499-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.