Abstract

Feedback is defined as a regulatory mechanism where the effect of an action is fed back to modify and improve future action. In medical education, newer conceptualizations of feedback place the learner at the center of the feedback loop and emphasize learner engagement in the entire process. But, learners reject feedback if they doubt its credibility or it conflicts with their self-assessment. Therefore, attention has turned to sociocultural factors that influence feedback-seeking, acceptance, and incorporation into performance. Understanding and application of specific aspects of psychosocial theories could help in designing initiatives that enhance the effect of feedback on learning and growth. In the end, the quality and impact of feedback should be measured by its influence on recipient behavior change, professional growth, and quality of patient care and not the skills of the feedback provider. Our objective is to compare and contrast older and newer definitions of feedback, explore existing feedback models, and highlight principles of relevant psychosocial theories applicable to feedback initiatives. Finally, we aim to apply principles from patient safety initiatives to emphasize a safe and just culture within which feedback conversations occur so that weaknesses are as readily acknowledged and addressed as strengths.

KEY WORDS: feedback, residency education, feedback culture, sociocultural theory, feedback credibility

The term “feedback” has its origin in mechanical environments and refers to an auto-regulatory mechanism where the effect of an action is fed back to modify future action. Based on whether the gap between actual and desired performance is narrowing or widening, the type of feedback is referred to as positive or negative feedback respectively. The term is now used in various professions in the context of performance appraisal and practice improvement. Once dominated by expert opinions and recommendations,1, 2 feedback in medical education has shifted its attention to feedback provider-recipient relationships and factors that promote acceptance and incorporation.3–5 In this perspective, we compare and contrast older and newer definitions of feedback, explore feedback practices and models used in medical education, and review tenets of relevant psychosocial theories applicable to the design of impact-enhancing feedback initiatives.

FEEDBACK: A VITAL COG IN THE WHEEL OF COMPETENCY-BASED MEDICAL EDUCATION

In the era of competency-based medical education, formative performance-based feedback is essential for learners to calibrate their performance and formulate action plans to narrow the gap between their current and expected performance.6–10 In several studies, medical students and residents report that faculty feedback is infrequently provided and vague language has little impact on their performance.4, 11–13 Clinical teachers report several barriers including lack of time and space for direct observation and feedback, lack of feedback skills, and concerns that “negative” feedback would damage teacher-learner relationships.14–17 Tackling complex barriers related to interpersonal relationships or institutional culture demands understanding of these factors.18–20

TRADITIONAL DEFINITIONS AND MODELS

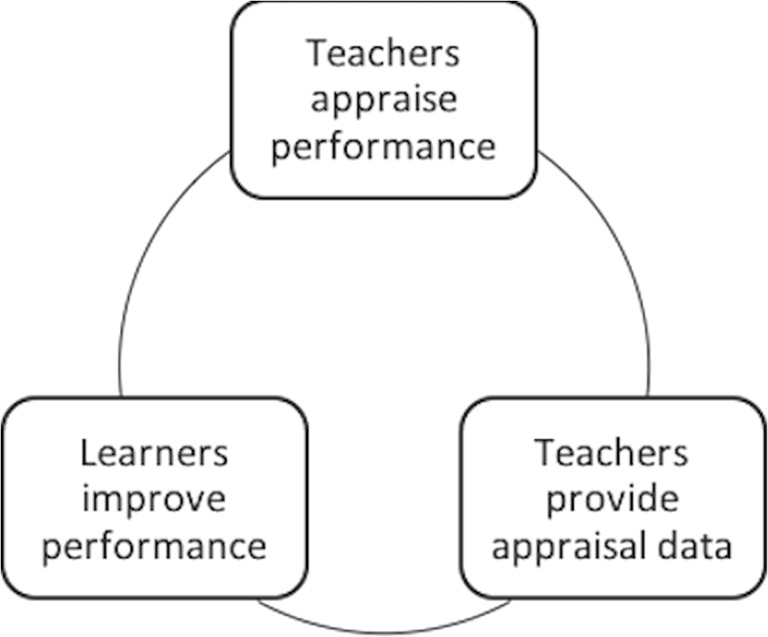

Older definitions of feedback emphasize teachers’ skills in providing feedback, a mostly unidirectional model for feedback conversations. Ende defined feedback in medical education as “information describing students or house officers’ performance in a given activity that is intended to guide their future performance in the same activity.”1 The “feedback sandwich” model, which recommends starting and ending with positive feedback, interposed by negative feedback,21 has not been shown to improve learner performance.22 The Pendleton model features four key steps: learner self-assessment of strengths, teacher agreement/disagreement, learner assessment of deficiencies, and teacher agreement/disagreement.23 However, most older definitions and models have not adequately showcased learner engagement in the conversation or their role in creating a road map for performance improvement. It had been assumed that improving teachers’ feedback skills would somehow lead learners to change practice and improve performance (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Older definitions and models of feedback in medical education are unidirectional with the direction of flow from teachers to learners. Learners’ performance improvement is assumed, and learning opportunities are not consistently created to allow for or document behavior change.

Recent research suggests that teachers’ perceptions of effective feedback may not be shared by learners, and teachers are largely unaware of when and why learners reject feedback.24–27 In Graduate Medical Education settings, residents are the first-line providers of patient care and it is important to preserve their self-esteem and autonomy during feedback conversations. Such settings warrant a learner-focused model with learners as active seekers of feedback and contributors to the conversation rather than passive recipients.4, 28 Short working relationships pose an additional barrier to learner-centered feedback approaches, yet, such approaches may be needed to promote behavior change. Therefore, the landscape of feedback needs to shift from teachers’ feedback techniques to learners’ goals, acceptance, and assimilation of feedback, regardless of the duration of working and learning relationships. To do this effectively, key factors that influence feedback acceptance need to be analyzed and understood.

FEEDBACK THROUGH A SOCIOCULTURAL LENS

Newer definitions of feedback emphasize its impact on recipients; until learners act on feedback, the feedback loop remains incomplete.3, 8, 9, 29, 30 However, learners reject constructive feedback, namely feedback on deficiencies or areas for improvement, if the process or provider lack credibility in their eyes.16, 31–33 Credibility is influenced by factors such as learner-teacher relationships, the manner of delivery, perceived intentions of feedback providers, direct observation of performance, congruence of data with self-assessment, and perceived threat to self-esteem or autonomy.17, 27, 30, 34–37 Two recent feedback models, the R2C2 model (relationships, reaction, content, and coaching) and the educational alliance model, place learners at the center of a feedback conversation and prioritize learner-teacher relationships as precursors to feedback conversations that target change in learner behavior and practice.38–42 Institutions need to promote trusting teacher-trainee relationships within a safe learning environment and facilitate regular direct observation of performance to enable meaningful feedback exchanges.4, 19

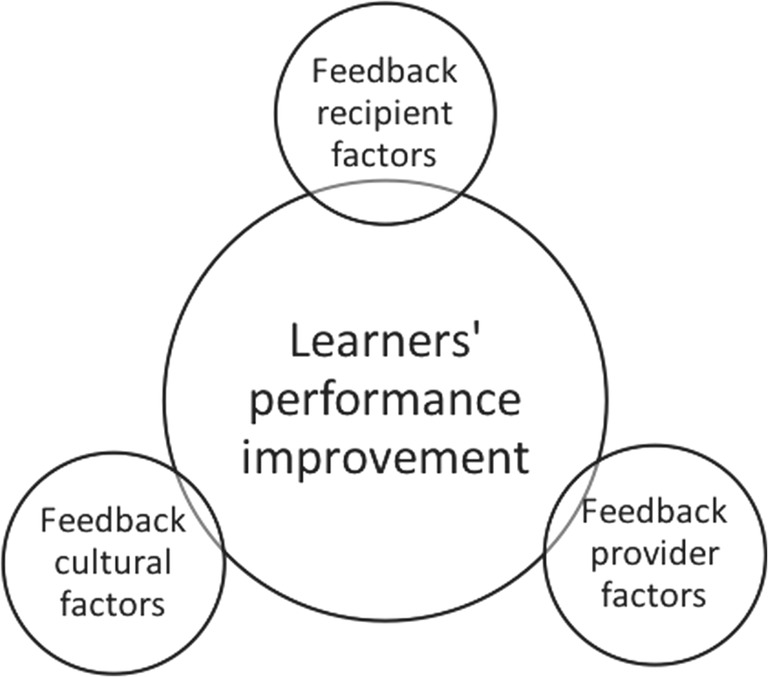

The feedback encounter is a complex exchange of information influenced by many factors such as the stress of the clinical environment, time pressures, emotional reactions, interpersonal tensions, and the learning culture.15, 16, 18 Although clinical supervisors are aware that feedback is intended to improve trainee performance, many struggle to provide constructive feedback as they do not wish to be seen as unkind, and wish to preserve self-esteem of and their relationship with trainees.16, 17, 19 Sociocultural factors that influence feedback can be examined through different viewpoints: the recipient, the provider, and the context. Figure 2 is a depiction of a central role for learners’ performance improvement in the feedback loop, influenced by factors related to feedback providers, recipients, and the institutional context.

Figure 2.

Sociocultural influences of feedback can be feedback provider related (teachers), feedback recipient related (learners), and feedback culture related (institutional). Learner-centered models of feedback emphasize the central position of learners in the feedback conversation with performance improvement as the end goal.

Feedback Recipients

Feedback models which cast learners as passive recipients are likely to be ineffective in graduate medical education; advanced trainees need to actively engage in appraisal of their practice.43 Feedback acceptance is influenced by feedback-seeking behaviors, ability to self-assess, and perceptions of threat to self-esteem.30, 44, 45 Goal-orientation of learners may also have a strong impact on feedback-seeking and acceptance.4, 43, 46, 47 Individuals with a performance goal-orientation seek feedback to showcase excellence and receive positive judgements;48, 49 they tend to reject feedback perceived as negative or threatening to their self-esteem.19, 37 Those with a learning goal-orientation focus on mastery of tasks and professional growth.48, 49 Institutions and teachers can promote a learning goal-orientation by emphasizing mastery of new knowledge and skills rather than appearance of excellence, normalizing areas for improvement, and communicating explicit messages that constructive feedback is necessary for performance improvement.

Feedback Providers

Medical education has historically focused on teachers’ skills in “providing” feedback to learners.1, 2, 50, 51 Its impact on learner behavior will likely be enhanced if feedback initiatives enhance teachers’ skills in promoting a positive learning climate, establishing rapport with learners, focusing on goal-directed feedback and action plans for performance improvement.30, 34, 52 It is essential that clinical teachers observe segments of their learners’ performance in a variety of domains, debrief observations in a timely manner, and provide opportunities for learners to implement action plans. Finally, it is important for teachers to encourage learner self-assessment and reflection to discuss both strengths and areas that need improvement.

Feedback Culture

A strong feedback culture promotes ongoing formal and informal feedback targeting continuous performance improvement.53, 54 Educational institutions can establish such a culture by facilitating trusting relationships between teachers and learners, building in time and space for feedback even in busy clinical settings and creating a shared understanding between teachers and learners about the process and content of feedback.16, 19, 55–57 More research is needed to explore how institutional culture can influence the quality and impact of feedback, feedback-seeking, acceptance, and performance improvement.5, 39, 41, 42 Understanding sociocultural factors in various learning and work environments is essential before designing initiatives to promote meaningful feedback exchanges and enhance its impact on behavior change and professional development.

THEORETICAL PRINCIPLES RELEVANT TO ENHANCING THE IMPACT OF FEEDBACK

Since recent research has described feedback as a complex interpersonal encounter with relationships playing an important role in learner acceptance and behavior change,4, 12, 18 it would be useful to explore sociocultural factors that impact feedback.3, 8, 15, 19, 27, 41 Specifically, concepts from three psychosocial theories are relevant to the sociocultural aspects of feedback: (1) sociocultural theory,58 (2) politeness theory,59 and (3) self-determination theory (Table 1).60 The theories highlight core principles that can guide development of new models and enhance techniques for effective feedback conversations, especially in clinical settings where learning occurs on teams. These principles include relatedness/relationships, self-efficacy, autonomy, and intrinsic motivation for continuous performance improvement and are described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Three Relevant Psychosocial Theories, Core Principles that Could Enhance the Impact of Feedback, and Corresponding Strategies to Address Those Principles

| Relevant psychosocial theory | Core principles | Implications for feedback strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Sociocultural theory |

Learning through social interactions Transformation through communities of practice Community influenced by cultural beliefs and assumptions |

Educators: - Identify learner abilities using a developmental approach - Calibrate gaps in learners’ current versus expected performance - Provide formative feedback to guide independent practice - Use coaching skills for learner growth Institutions: - Provide a safe and just team culture - Establish trusting teacher-learner working relationships - Encourage communities of practice on clinical teams and in training programs |

| Politeness theory |

Self-efficacy/self-image Autonomy/freedom from imposition by others |

Educators: - Initiate feedback conversations with previous examples of excellence - Obtain learner goals and engage in goal-directed feedback - Facilitate learner reflections to calibrate gap between current performance and expected performance - Co-create action plans for improvement and future learning opportunities - Focus on professional growth and patient care outcomes Institutions: - Facilitate teacher-learner relationships - Encourage direct observation of performance - Train teachers to provide constructive feedback based on observed behaviors - Orient learners to seek feedback and train them to accept feedback and incorporate into performance - Establish an environment of gradual, increasing, and appropriate autonomy for learners - Shift from performance to learning goal-orientation |

| Social determinant theory |

Autonomy Relatedness Intrinsic motivation |

Educators: - Shift the focus from the individual to the context - Shift from instructional messages to self-regulation - Shift the focus from the perspective of feedback providers to recipients - Direct observation of performance - Encourage self-reflection and self-assessment - Challenge learners in a supportive environment Institutions: - Establish a safe and just culture - Set expectations for ongoing formative feedback - Encourage continuous improvement mindset - Stimulate learning goal-orientation - Emphasize excellence and safety in patient care |

Sociocultural theory, which proposes that humans learn largely through social interactions influenced by cultural beliefs and attitudes, grew from the work of Vygotksy.61 Drawing upon this theory, Lave and Wenger describe that individuals transform through participation in communities of practice.58 As learners assume increasing responsibility for their activities, they move from the periphery to the center of a community. Since clinical learning occurs through team interactions and collaboration, institutions should attend to the broader community in which learning is occurring as well as development of individual learners within these communities. Applying these principles to feedback, educators need to (a) identify learner abilities using a developmental approach, (b) calibrate gaps in learners’ current versus expected performance, and (c) provide formative feedback to guide independent practice.

Concepts from Brown and Levinson’s politeness theory are relevant to feedback conversations. This theory, from the field of linguistic pragmatics, proposes that two types of “face,” positive and negative, play a role in most social interactions.59, 62 The positive face reflects an individual’s need to be appreciated by others, and the negative face reflects an individual’s need for freedom of action. The clinical environment is characterized by interpersonal relationships between teachers and learners, and multiple team members. In such settings, constructive feedback may be perceived as “negative” and thus a breach of the norms of expected politeness. Honest constructive feedback is essential for longitudinal growth as self-affirmation alone is not the path to professional improvement. However, clinical teachers tend to emphasize positive performance during feedback exchanges to avoid damaging teacher-learner relationships and learner self-esteem.15, 31 Thus, a polite or face-saving learning culture may have a negative impact on feedback conversations, an area that warrants further research.63

Self-determination theory, described by Ryan and Deci, states that human beings tend to regulate behaviors autonomously, take on challenges, and learn through intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation.60 Extrinsic motivation is driven by external factors with the goal of achieving defined outcomes.60 Intrinsically motivated individuals take on activities for inherent satisfaction rather than to achieve a given result.60 We propose that intrinsic motivation would positively influence feedback-seeking, acceptance, and assimilation, therefore performance improvement. Ten Cate et al. suggest approaches to boost intrinsic motivation during feedback conversations: shifting the focus from the individual to the context; shifting from instructional messages to self-regulation; and shifting the focus from the perspective of feedback providers to recipients.64

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Based on evolving acknowledgement that feedback is a learner-centered and sociocultural phenomenon, it is important to swing the pendulum of feedback research and faculty development from teacher techniques to learner outcomes. Medical educators should examine what institutional cultural factors influence the quality and impact of feedback conversations at their own institutions from multiple perspectives. Observational studies are necessary to examine teacher and learner behaviors during feedback conversations and explore whether intentions of speakers match the perceptions of receivers. Co-construction of feedback conversations, action plans for improvement, and new learning opportunities by teachers and learners are more likely to result in professional growth.39, 42 Finally, the most credible feedback on clinical performance might be from patients to fulfill the ultimate goal of high-quality and safe patient care. Integration of patient feedback into performance assessment is fraught with challenges, but if implemented effectively, it could trigger meaningful behavior change and enhance safety and quality in patient care.65 More research is needed in this important area.

Applying principles from patient safety initiatives, we propose that educational institutions adopt a fair and just culture within which feedback is exchanged. Such an organizational culture ensures learning and continuous improvement through acknowledgement of areas of weaknesses as well as areas of excellence, willingness to seek help, focus on humanism and accountability to excellent care.66–68 Institutions have a major role in establishing this culture to mitigate the effects of the hierarchical clinical environment, empower learners to take ownership of their professional growth, and enable collaborative bidirectional feedback. This empowerment can be driven by explicit expectations for collaborative calibration of performance against expected goals and clear messages that all professionals have strengths and areas for improvement. Focus on reflective practice, lifelong learning, and continuous improvement is essential for safe and high-quality patient care.

Relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.69 After all, why should feedback conversations be any different than skilled physician-patient communications, with a focus on rapport, learner self-reflection, and shared decision-making?

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branch WT, Jr, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77:1185–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molloy E, Boud D. Seeking a different angle on feedback in clinical education: the learner as seeker, judge and user of performance information. Med Educ. 2013;47:227–9. doi: 10.1111/medu.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302:1330–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated Reflective Performance Feedback: Developing an Evidence- and Theory-Based Model That Builds Relationship, Explores Reactions and Content, and Coaches for Performance Change (R2C2) Acad Med. 2015;90:1698–706. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Edgar L, et al. Reflections on the First 2 Years of Milestone Implementation. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:506–11. doi: 10.4300/JGME-07-03-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tekian A, Watling CJ, Roberts TE, Steinert Y, Norcini J. Qualitative and quantitative feedback in the context of competency-based education. Med Teach. 2017;39:1245–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1372564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boud D. Feedback: ensuring that it leads to enhanced learning. Clin Teach. 2015;12:3–7. doi: 10.1111/tct.12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Ridder JM, Stokking KM, McGaghie WC, ten Cate OT. What is feedback in clinical education? Med Educ. 2008;42:189–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson PA. Giving feedback on clinical skills: are we starving our young? J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:154–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-000295.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delva D, Sargeant J, Miller S, et al. Encouraging residents to seek feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35:e1625–31. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bing-You RG, Paterson J, Levine MA. Feedback falling on deaf ears: residents’ receptivity to feedback tempered by sender credibility. Med. Teach. 1997;19:40–4. doi: 10.3109/01421599709019346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sender Liberman A, Liberman M, Steinert Y, McLeod P, Meterissian S. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005;27:470–2. doi: 10.1080/0142590500129183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudek NL, Marks MB, Regehr G. Failure to fail: the perspectives of clinical supervisors. Acad Med. 2005;80:S84–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sargeant J, McNaughton E, Mercer S, Murphy D, Sullivan P, Bruce DA. Providing feedback: exploring a model (emotion, content, outcomes) for facilitating multisource feedback. Med Teach. 2011;33:744–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sargeant J, Mann K, Sinclair D, Van der Vleuten C, Metsemakers J. Understanding the influence of emotions and reflection upon multi-source feedback acceptance and use. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13:275–88. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramani S, Konings KD, Mann KV, Pisarski EE, van der Vleuten CPM. About Politeness, Face, and Feedback: Exploring Resident and Faculty Perceptions of How Institutional Feedback Culture Influences Feedback Practices. Acad Med. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Watling CJ. Unfulfilled promise, untapped potential: feedback at the crossroads. Med Teach. 2014;36:692–7. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Beyond individualism: professional culture and its influence on feedback. Med Educ. 2013;47:585–94. doi: 10.1111/medu.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delva D, Sargeant J, MacLeod T. Feedback: a perennial problem. Med Teach. 2011;33:861–2. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.618042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dohrenwend A. Serving up the feedback sandwich. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkes J, Abercrombie S, McCarty T. Feedback sandwiches affect perceptions but not performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013;18:397–407. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pendleton D. The Consultation : an approach to learning and teaching. Oxford, Oxfordshire, New York: Oxford University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archer J. Feedback: it’s all in the CHAT. Med Educ. 2013;47:1059–61. doi: 10.1111/medu.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen AR, Wright AS, Kim S, Horvath KD, Calhoun KE. Educational feedback in the operating room: a gap between resident and faculty perceptions. Am J Surg. 2012;204:248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bing-You RG, Varaklis K, Hayes V, et al. The feedback tango: an integrative review and analysis of the content of the teacher-learner feedback exchange. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):657–63. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watling C. Cognition, culture, and credibility: deconstructing feedback in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3:124–8. doi: 10.1007/s40037-014-0115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watling CJ, Kenyon CF, Zibrowski EM, et al. Rules of engagement: residents’ perceptions of the in-training evaluation process. Acad Med. 2008;83:S97–100. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183e78c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boud D, Molloy E. Feedback in higher and professional education : understanding it and doing it well. London, New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Ridder JM, McGaghie WC, Stokking KM, ten Cate OT. Variables that affect the process and outcome of feedback, relevant for medical training: a meta-review. Med Educ. 2015;49:658–73. doi: 10.1111/medu.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann K, van der Vleuten C, Eva K, et al. Tensions in informed self-assessment: how the desire for feedback and reticence to collect and use it can conflict. Acad Med. 2011;86:1120–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226abdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sargeant J, Mann K, Sinclair D, van der Vleuten C, Metsemakers J. Challenges in multisource feedback: intended and unintended outcomes. Med Educ. 2007;41:583–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sargeant J, Mann K, Ferrier S. Exploring family physicians’ reactions to multisource feedback: perceptions of credibility and usefulness. Med Educ. 2005;39:497–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Ridder JM, Berk FC, Stokking KM, Ten Cate OT. Feedback providers’ credibility impacts students’ satisfaction with feedback and delayed performance. Med Teach. 2014;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Harrison CJ, Konings KD, Molyneux A, Schuwirth LW, Wass V, van der Vleuten CP. Web-based feedback after summative assessment: how do students engage? Med Educ. 2013;47:734–44. doi: 10.1111/medu.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison CJ, Könings KD, Schuwirth L, Wass V, van der Vleuten C. Barriers to the uptake and use of feedback in the context of summative assessment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20:229–45. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaunt A, Patel A, Rusius V, Royle TJ, Markham DH, Pawlikowska T. ‘Playing the game’: How do surgical trainees seek feedback using workplace-based assessment? Med Educ. 2017;51:953–62. doi: 10.1111/medu.13380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated Reflective Performance Feedback: Developing an Evidence- and Theory-Based Model That Builds Relationship, Explores Reactions and Content, and Coaches for Performance Change (R2C2). Acad Med. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Sargeant J, Lockyer JM, Mann K, et al. The R2C2 Model in Residency Education: How Does It Foster Coaching and Promote Feedback Use? Acad Med. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sargeant J, Mann K, Manos S, et al. R2C2 in Action: Testing an Evidence-Based Model to Facilitate Feedback and Coaching in Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:165–70. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00398.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telio S, Ajjawi R, Regehr G. The “educational alliance” as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90:609–14. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Telio S, Regehr G, Ajjawi R. Feedback and the educational alliance: examining credibility judgements and their consequences. Med Educ. 2016;50:933–42. doi: 10.1111/medu.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teunissen PW, Bok HG. Believing is seeing: how people’s beliefs influence goals, emotions and behaviour. Med Educ. 2013;47:1064–72. doi: 10.1111/medu.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eva KW, Armson H, Holmboe E, et al. Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9290-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ten Cate OT. Why receiving feedback collides with self determination. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013;18:845–9. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Acad Med. 2009;84:910–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a858ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Spruijt A, et al. Clarifying students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in clinical clerkships. Med Educ. 2013;47:282–91. doi: 10.1111/medu.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dweck CS. Mindsets and human nature: promoting change in the Middle East, the schoolyard, the racial divide, and willpower. Am Psychol. 2012;67:614–22. doi: 10.1037/a0029783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dweck CS. Self-theories and goals: their role in motivation, personality, and development. Nebr Symp Motiv. 1990;38:199–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramani S, Krackov SK. Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2012;34:787–91. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.684916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van de Ridder JM, Peters CM, Stokking KM, de Ru JA, Ten Cate OT. Framing of feedback impacts student’s satisfaction, self-efficacy and performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20:803–16. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.London M, Smither JW. Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2002;12:81–100. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4822(01)00043-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Lingard L. Learning culture and feedback: an international study of medical athletes and musicians. Med Educ. 2014;48:713–23. doi: 10.1111/medu.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Music lessons: revealing medicine’s learning culture through a comparison with that of music. Med Educ. 2013;47:842–50. doi: 10.1111/medu.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Archer JC. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med Educ. 2010;44:101–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kraut A, Yarris LM, Sargeant J. Feedback: Cultivating a Positive Culture. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:262–4. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00103.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning : legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, England, New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown P, Levinson SC. Politeness : some universals in language usage. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wertsch JV. Voices of the mind : a sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1991.

- 62.Brown P, Levinson S. Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramani S, Post SE, Konings K, Mann K, Katz JT, van der Vleuten C. “It’s Just Not the Culture”: A Qualitative Study Exploring Residents’ Perceptions of the Impact of Institutional Culture on Feedback. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29:153–61. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1244014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ten Cate TJ, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2011;33:961–73. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.595435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baines R, Regan de Bere S, Stevens S, et al. The impact of patient feedback on the medical performance of qualified doctors: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:173. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rider EA, Gilligan MC, Osterberg LG, et al. Healthcare at the Crossroads: The Need to Shape an Organizational Culture of Humanistic Teaching and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Frankel AS, Leonard MW, Denham CR. Fair and just culture, team behavior, and leadership engagement: The tools to achieve high reliability. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1690–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boysen PG., 2nd Just culture: a foundation for balanced accountability and patient safety. Ochsner J. 2013;13:400–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med Teach. 2018;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]