Abstract

Background: It remains unclear whether constipation is associated with cancer. We evaluated the risk of malignancies in patients with constipation requiring hospitalization.

Methods: Using Danish medical registries, we calculated cumulative incidences and standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for cancer. SIRs were computed as the observed number of gastrointestinal (GI) cancers and selected non-GI cancers in patients with constipation compared with the expected number based on national incidence rates by sex, age, and calendar year (1978–2013).

Results: We identified 1,75,901 patients with constipation (59% females, median age 54 years). The cumulative incidences of GI cancers and non-GI cancers after 15 years of follow-up were 2.5% and 2.6%, respectively. During the first year of follow-up, the SIR for any GI cancer was 5.0 (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.8–5.3), driven by colon and pancreas cancers and higher for younger age groups. Beyond 1 year of follow-up, the risk declined to near unity for colorectal cancer. The risk of other GI cancers (including cancers of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, liver, and pancreas) remained moderately increased (overall SIR =1.3, 95% CI: 1.2–1.4). Except for ovarian cancer (SIR =7.3, 95% CI: 6.3–8.4), the risk of non-GI cancers was only slightly increased during the first year of follow-up and declined to unity thereafter.

Conclusions: Patients with constipation had increased short-term risk of a diagnosis of GI cancer. Beyond 1 year of follow-up, a moderately elevated risk persisted only for GI cancers other than colorectal cancer. The risk of non-GI cancers was elevated only during the first year of follow-up, particularly for ovarian cancer.

Keywords: constipation, cancer, cohort study

Introduction

Constipation is a common condition worldwide.1,2 Because many individuals do not seek medical advice, its prevalence is not easily estimated.3 Available data suggest that prevalence ranges from 2.5% to 79% in adults, depending on age, sex, and definition of constipation and prevalence.2,4,5 Risk factors include low fiber diet, no physical activity, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Hirschsprung’s disease, endocrine diseases, and various medications such as opioids.5–9

Constipation may be associated with cancer through several mechanisms. First, Burkitt et al hypothesized in 1971 that decreased gut motility may increase the long-term risk of colorectal cancer because of increased transit time.10 This would cause prolonged duration of contact between the colonic mucosa and carcinogens in the stool. Second, increased attention has been given to the link between the human gut microbiota and cancers in recent decades.11 It has been proposed that dysbiosis in the microbiota is associated with inflammatory disorders and various cancers.12,13 In addition, circulating toxic metabolites from the microbial cells are thought to disseminate to other locations in the body and thereby contribute to cancer development, onset, or progression.14,15 Third, any association with constipation also may be due to reverse causation, ie, gastrointestinal (GI) cancers may cause constipation before the cancer manifests clinically. Finally, constipation and certain cancers may be independent, but convergent, diseases caused by common underlying risk factors, with a longer latency period for clinically detectable cancer.

Previous studies have focused mainly on the association between constipation and colorectal cancer, with conflicting results.16–23 Only a few studies found an association with other GI cancers, such as gall bladder cancer,24,25 and non-GI cancers including ovarian cancer and breast cancer.26,27 In general, these studies were limited by selection bias, recall bias, and self-reported information on constipation.17–27

Therefore, we investigated the risk of a wide range of GI cancers and selected non-GI cancers in a large cohort of patients diagnosed with constipation, compared with risks in the general population. In all analyses, we examined short-term cancer risk to focus on undetected prevalent occult cancers, and long-term risk to focus on incident cancers, which may be associated with constipation through shared risk factors.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study of patients with a hospital contact for constipation from 1 January 1978 to 30 November 2013. During this period, the cumulative Danish population numbered 8.38 million inhabitants. The Danish National Health Service provides tax-supported health care for all Danish residents, with free and equal access to general practitioners and to hospital inpatient and outpatient care.

Data sources

At birth or upon immigration, all Danish residents are assigned a unique personal identifier, the civil registration number. This number is recorded in the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS), which also contains information on date of death and emigration from the country. With daily electronic updates, the CRS allows virtually complete follow-up of the Danish population.28,29 The civil registration number permits individual-level linkage among numerous Danish registries.28

Since 1977, the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) has collected complete data on diagnoses and procedures for all patients discharged from Danish non-psychiatric hospitals. The data were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8) until 1993 and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) thereafter. From 1995, data on hospital outpatient visits have been included in the registry. Each hospital discharge or outpatient visit is recorded with one primary diagnosis and up to nineteen secondary diagnoses.30

The Danish Cancer Registry (DCR) has recorded information on all cases of incident cancer since 1943.31 Cancers diagnosed before 2004 have been re-coded into the ICD-10 format. Completeness of DCR data was high throughout the study period, although mandatory reporting to the DCR was first implemented in 1987.32

Study population and constipation classification

We used the DNPR to identify patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation from 1 January 1978 through 30 November 2013. We included both primary and secondary diagnoses from first-time inpatient, outpatient specialist clinic, and emergency room hospital contacts for constipation. Patients with a prior history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) were excluded (Table S1).

Table S1.

Diagnosis and procedure codes used in the study

| ICD-8 | ICD-10 | Procedure codes (1978–1995) | Procedure codes (1996–2013) | Surgery codes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constipation | 564.00, 564.09 | DK590 | |||

| Cancers | |||||

| Gastrointestinal cancers | DC15–26 (expect morphology codes 809,879) | ||||

| Colorectal cancers | DC18–20 | ||||

| Other gastrointestinal cancers | DC15–17, DC21–26 (expect morphology codes 809,879) | ||||

| Hormone-related cancers | DC50, DC54–56, DC61–62, DC73, | ||||

| Lymphoma | DC81–85, DC90 | ||||

| Lower endoscopy | 91070, 91080 | KUJF32- KUJF35 KUJF42–45, KJFA15 – KJGA05 |

|||

| Surgery on the small intestine, colon, or anal canal | KJG, KJF | ||||

| Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis and paralytic ileus) | 563.19, 560.19, 563.01 | K50, K51, K56 | |||

| Diabetes | 24900-25009, 25390, 27380 | E10, E11, H36.0 | |||

| Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease | 340.00–340.09, 342.99, 34809 | G20, G35 | |||

| Myxedema | 243.99–244.09 | E03 |

Cancer outcome

We included a wide range of GI cancers, including cancers of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, anal canal, liver, gall bladder and biliary tract, and pancreas. In addition, we included selected non-GI cancers that may cause constipation before the cancer is diagnosed or share risk factors with constipation. These included hormone-related cancers (cancers of the breast, corpus uteri, ovary, prostate, testes, and thyroid gland) and lymphomas (Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas and non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas) (Table S1).

Statistical analyses

We computed cumulative incidences of cancers up to 15 years following first-time hospital contact for constipation, accounting for death as a competing risk.33 Follow-up was initiated on the first date that constipation was diagnosed and continued until any predefined incident cancer outcome, death, emigration, 15 years of follow-up, or 30 November 2013.

Any excess short-term cancer risk likely involves prevalent, but undiagnosed, cancers that cause constipation before the cancer itself becomes clinically overt. Any excess long-term risk likely represents incident cancers. Therefore, we used two follow-up periods in our analyses (0–1 year of follow-up and 2–15 years of follow-up). Based on national incidence rates of cancers by age, sex, and year of cancer diagnosis in 1-year intervals, we calculated the expected number of incident cancers in patients with constipation, assuming the same risk of cancer as in the general population. The expected number of cancers was obtained by multiplying the number of person-years of observation by the population-based cancer incidence rates.

The relative cancer risk in patients with constipation was computed as the standardized incidence ratio (SIR), ie, the ratio of the observed vs the expected number of cancer cases. Associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived using Byar’s approximation, assuming that the observed number of cases in a specific category followed a Poisson distribution. We used exact 95% CIs when the observed number of cancers was less than ten.34

We stratified the analyses by inpatient admissions, outpatient visits, and emergency room visits (from 1995 onwards) because inpatients are often acutely admitted to hospital while outpatient visits are based on elective referrals. Furthermore, we stratified the analyses by sex, age at constipation diagnosis (0–17 years, 18–34 years, 35–49 years, 50–64 years, and ≥65 years), and calendar year of constipation diagnosis (1978–1985, 1986–1993, 1994–2001, 2002–2009, and 2010–2013). Finally, we stratified the analyses by comorbid diseases based on a modified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (excluding cancers from the Index) (Table S2).

Table S2.

Codes for conditions included in the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index

| Comorbidities | Weight | ICD-8 | ICD-10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 410 | I21; I22; I23 |

| Congestive heart failure | 427.09; 427.10; 427.11; 427.19; 428.99; 782.49 | I50; I11.0; I13.0; I13.2 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 440; 441; 442; 443; 444; 445 | I70; I71; I72; I73; I74; I77 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430–438 | I60-I69; G45; G46 | |

| Dementia | 290.09-290.19; 293.09 | F00-F03; F05.1; G30 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 490–493; 515-518 | J40-J47; J60-J67; J68.4; J70.1; J70.3; J84.1; J92.0; J96.1; J98.2; J98.3 |

|

| Connective tissue disease | 712; 716; 734; 446; 135.99 | M05; M06; M08; M09; M30; M31; M32; M33; M34; M35; M36; D86 |

|

| Ulcer disease | 530.91; 530.98; 531–534 | K22.1; K25–K28 | |

| Mild liver disease | 571; 573.01; 573.04 | B18; K70.0–K70.3; K70.9; K71; K73; K74; K76.0 | |

| Diabetes without end-organ damage | 249.00, 249.06, 249.07, 249.09, 250.00, 250.06, 250.07, 250.09 | E10.0, E10.1, E10.9, E11.0, E11.1, E11.9 | |

| Diabetes with end-organ damage | 2 | 249.01-249.05, 249.08, 250.01-250.05, 250.08 | E10.2- E10.8, E11.2-E11.8 |

| Hemiplegia | 344 | G81; G82 | |

| Moderate to severe renal disease | 403; 404; 580–583; 584; 590.09; 593.19; 753.10–753.19; 792 | I12; I13; N00–N05; N07; N11; N14; N17–N19; Q61 | |

| Moderate to severe liver disease | 3 | 070.00; 070.02; 070.04; 070.06; 070.08; 573.00; 456.00-456.09 | B15.0; B16.0; B16.2; B19.0; K70.4; K72; K76.6; I85 |

| AIDS | 6 | 079.83 | B21–B24 |

To investigate the impact of lower endoscopy on risk of colorectal cancer, we conducted a subanalysis stratified by presence/absence of lower endoscopy (colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy) during diagnostic work-up, eg, from 3 months before to 4 weeks after the constipation diagnosis. To avoid conditioning on the future, we initiated follow-up four weeks after the constipation diagnosis. This analysis was based on endoscopies identified from Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures codes (Table S1).

In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the main analyses, restricting to patients with primary and secondary diagnoses of constipation. A primary diagnosis indicates that constipation was the main reason for the hospital contact and registration may, therefore, have higher accuracy. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number 1-16-02-1-08). Studies based on registry data in Denmark do not require informed consent. The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing our results or replicating our procedures. Such disclosure would conflict with the regulations for use of Danish health care data.

Results

We identified 175,901 patients registered with a hospital-based diagnosis of constipation during the study period (median age 54 years, 59% female) (Table 1). Total person time at risk was 1,111,441 person-years, with median follow-up time of 4.8 years (interquartile range =1.7–11 years). The study cohort consisted of 125,377 (71%) inpatients, 40,478 (23%) outpatients, and 10,046 (6%) emergency room patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation in Denmark during 1978–2013

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Overall | 175,901 (100) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 104,106 (59) |

| Male | 71,795 (41) |

| Type of hospital contact | |

| Inpatient | 125,377 (71) |

| Outpatient | 40,478 (23) |

| Emergency room visit | 10,046 (6) |

| Calendar period of constipation diagnosis | |

| 1978–1985 | 22,136 (13) |

| 1986–1993 | 21,505 (13) |

| 1994–2001 | 34,393 (20) |

| 2002–2009 | 57,144 (33) |

| 2010–2013 | 40,723 (23) |

| Age at diagnosis of constipation (years) | |

| 0–17 | 49,531 (28) |

| 18–34 | 16,971 (10) |

| 35–49 | 16,002 (9) |

| 50–64 | 21,313 (12) |

| 65+ | 72,084 (41) |

| Lower endoscopya | 24,194 (13.8) |

| Surgery on the small intestine, colon, or anal canalb | 2,588 (1.5) |

| Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index scorec | |

| Low | 117,596 (67) |

| Moderate | 45,305 (26) |

| Severe | 13,000 (7) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10,405 (6) |

| Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis | 3,202 (2) |

| Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis | 5,692 (3) |

| Myxedema | 1,371 (1) |

Notes: aPerformed in the period from 3 months prior to 4 weeks following the constipation diagnosis. bPerformed in the period from 3 months prior to 3 months following the constipation diagnosis. cCategories of comorbidity were based on modified Charlson Comorbidity Index scores: 0, low; 1–2, moderate; ≥3, severe.

Table 3.

Standardized incidence ratios for selected cancers in patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation, by sex, age group, calendar year, type of hospital contact, and comorbidity level, Denmark, 1978–2013

| Gastrointestinal cancers | Colorectal cancers | Other gastrointestinal cancersa | Hormone-related cancers | Lymphomas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 years after constipation diagnosis | |||||

| Total | 5.0 (4.8–5.3) | 5.2 (4.9–5.5) | 4.8 (4.5–5.2) | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | 3.4 (3.0–3.9) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 5.1 (4.7–5.4) | 5.2 (4.8–5.7) | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 2.6 (2.0–3.2) |

| Male | 5.0 (4.7–5.4) | 5.1 (4.7–5.5) | 4.9 (4.4–5.5) | 2.5 (2.3–2.8) | 4.3 (3.6–5.1) |

| Age group at constipation diagnosis (years) | |||||

| 0–17 | 13.6 (2.8–39.8) | – | 15.9 (3.3–46.3) | 8.7 (1.2–31.6) | 14.8 (6.8–28.2) |

| 18–34 | 28.8 (14.9–50.3) | 34.4 (15.7–65.3) | 19.4 (4.0–56.7) | 2.8 (1.2–5.6) | 3.4 (0.7–10.0) |

| 35–49 | 12.2 (9.0–16.1) | 13.1 (8.8–18.6) | 11.0 (6.6–17.2) | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) | 7.8 (4.2–13.4) |

| 50–64 | 9.9 (8.8–11.0) | 10.0 (8.6–11.6) | 9.7 (8.1–11.5) | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | 5.3 (3.7–7.3) |

| ≥65 | 4.5 (4.2–4.7) | 4.6 (4.3–4.9) | 4.2 (3.9–4.6) | 2.2 (2.0–2.3) | 2.9 (2.4–3.4) |

| Calendar year of constipation diagnosis | |||||

| 1978–1985 | 3.5 (3.1–4.1) | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) | 4.5 (3.7–5.4) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 2.9 (1.8–4.5) |

| 1986–1993 | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 3.6 (3.0–4.3) | 3.1 (2.4–3.9) | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 2.8 (1.7–4.2) |

| 1994–2001 | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 4.9 (4.2–5.5) | 4.1 (3.4–5.0) | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | 3.0 (2.1–4.2) |

| 2002–2009 | 6.0 (5.6–6.5) | 6.2 (5.6–6.7) | 5.8 (5.1–6.6) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 3.8 (3.0–4.7) |

| 2010–2013 | 6.6 (5.9–7.2) | 6.9 (6.1–7.8) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 3.9 (2.9–5.1) |

| Type of hospital contact | |||||

| Inpatient | 5.0 (4.8–5.3) | 5.1 (4.8–5.5) | 4.8 (4.4–5.3) | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | 3.5 (3.0–4.1) |

| Outpatient clinic | 3.7 (3.2–4.2) | 3.5 (2.9–4.2) | 4.0 (3.2–5.0) | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | 2.6 (1.7–3.7) |

| Emergency room | 9.5 (8.2–11.0) | 10.8 (9.0–12.8) | 7.4 (5.5–9.7) | 3.1 (2.4–3.9) | 5.1 (3.0–8.2) |

| Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index scoreb | |||||

| Low (0) | 6.3 (5.9–6.7) | 6.8 (6.3–7.4) | 5.5 (4.9–6.1) | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 4.3 (3.5–5.1) |

| Moderate (1–2) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 4.0 (3.6–4.4) | 4.6 (4.1–5.2) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) |

| High (3+) | 3.3 (2.8–3.8) | 3.2 (2.6–4.0) | 3.3 (2.5–4.3) | 1.6 (1.2–1.9) | 2.9 (1.9–4.4) |

| 2–15 years after constipation diagnosis | |||||

| Total | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| Male | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Age group at constipation diagnosis (years) | |||||

| 0–17 | – | – | – | 1.0 (0.9–1.9) | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) |

| 18–34 | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | 2.3 (1.1–4.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 1.6 (0.9–2.6) |

| 35–49 | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 2.4 (1.8–3.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) |

| 50–64 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| ≥65 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| Calendar year of constipation diagnosis | |||||

| 1978–1985 | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| 1986–1993 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| 1994–2001 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 2002–2009 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| 2010–2013 | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) |

| Type of hospital contact | |||||

| Inpatient | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) |

| Outpatient clinic | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) |

| Emergency room | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) |

| Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index scoreb | |||||

| Low (0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) |

| Moderate (1–2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) |

| High (3+) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) |

Notes: Insufficient for estimation, due to less than 5 observed cancer cases. aIncluding cancers of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, anal canal, liver, gall bladder and biliary tract, pancreas, and other poorly specified gastrointestinal cancers. bComorbidities are specified in Table S2.

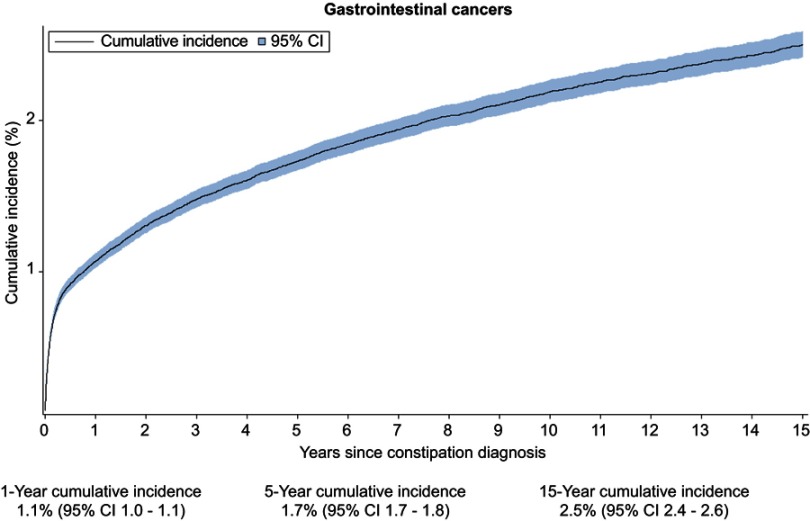

GI cancers

The cumulative incidence of GI cancers was 1.1% after 1 year of follow-up and 2.5% after 15 years of follow-up (Figure 1). During the first year of follow-up, our analysis yielded SIRs of 5.2 (95% CI: 4.9–5.5) for colorectal cancer and 4.8 (95% CI: 4.5–5.2) for GI cancers other than colorectal cancer. Risk of colorectal cancer was driven mainly by cancer in the colon (SIR =6.4, 95% CI: 6.0–6.8), whereas risk of GI cancers other than colorectal cancer was driven mainly by smoking-/alcohol-related cancers, including cancers of the pancreas (SIR =7.1, 95% CI: 6.3–7.9), stomach (SIR =3.6, 95% CI: 3.1–4.3), and liver (SIR =4.2, 95% CI: 3.3–5.4) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with a hospital-based diagnosis of constipation.a

Notes:aIncluding patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation in Denmark during 1978–2013, accounting for death as a competing risk.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Standardized incidence ratios for colorectal cancers in patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation, by presence/absence of a lower endoscopy performed in the period from 3 months prior to 4 weeks following the constipation diagnosis, Denmark, 1978–2013

| Colorectal cancers diagnosed ≥4 weeks – 1 year from constipation diagnosisa | Colorectal cancers diagnosed ≥1 year from constipation diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | E | SIR (95% CI) | O | E | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Endoscopy (N=24,194) | 112 | 38.8 | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) | 121 | 185.3 | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) |

| No Endoscopy (N=144,751) | 451 | 168.0 | 2.7 (2.4–2.9) | 734 | 837.3 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

Note: aFollow-up was initiated 4 weeks after the constipation diagnosis because the analysis was conditioned on lower endoscopy up until 4 weeks after the constipation diagnosis.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; E, expected number of cases; O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

During 2–15 years of follow-up, the SIR was 0.8 (95% CI: 0.8–0.9) for colorectal cancer, driven by rectal cancer (SIR =0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.6), and the SIR was 1.3 (95% CI: 1.2–1.4) for GI cancers other than colorectal cancer. Similar to the first year of follow-up, the risk of GI cancers other than colorectal cancer during 2–15 years of follow-up was driven mainly by smoking-/alcohol-related cancers, including cancers of the stomach (SIR =1.2, 95% CI: 1.0–1.3), pancreas (SIR =1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5), and liver (SIR =1.7, 95% CI: 1.4–2.0) (Table 2). After stratifying by sex, age at constipation diagnosis, type of hospital contact, calendar period, and level of comorbidity, 2–15-year risk of colorectal cancer and other GI cancers remained consistent with the main results, whereas we observed stronger associations for younger age groups and more recent calendar periods during the first year of follow-up (Table 3).

Table 5.

Standardized incidence ratios for cancer in patients with constipation by type of hospital diagnosis, Denmark, 1978–2013

| Cancers diagnosed 0–1 year after constipation diagnosis | Cancers diagnosed 2–15 years after constipation diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | E | SIR (95% CI) | O | E | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 1401 | 249.2 | 5.6 (5.3–5.9) | 1205 | 1184.8 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| Colorectal cancers | 903 | 153.9 | 5.9 (5.5–6.3) | 610 | 738.5 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Other gastrointestinal cancers | 498 | 95.2 | 5.2 (4.8–5.7) | 595 | 446.3 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) |

| Hormone-related cancers | 602 | 282.6 | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | 1440 | 1487.6 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

| Lymphoma | 130 | 41.1 | 3.2 (2.7–3.8) | 233 | 213.3 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

| Secondary diagnosis | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 581 | 150.5 | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 574 | 570.4 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Colorectal cancers | 346 | 93.4 | 3.7 (3.3–4.1) | 311 | 355.6 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Other gastrointestinal cancers | 235 | 57.1 | 4.1 (3.6–4.7) | 263 | 214.8 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) |

| Hormone-related cancers | 332 | 158.0 | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 598 | 651.0 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| Lymphoma | 84 | 23.5 | 3.6 (2.9–4.4) | 110 | 95.9 | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; E, expected number of cases; O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

In the analysis stratified by presence/absence of lower endoscopy in the period 3 months prior to 4 weeks after the constipation diagnosis, the SIR for colorectal cancer during the first year of follow-up was 2.9 (95% CI: 2.4–3.5) in patients undergoing lower endoscopy and 2.7 (95% CI: 2.4–2.9) in patients who did not undergo this procedure. During 2–15 years of follow-up, the corresponding estimates were 0.7 (95% CI: 0.5–0.8) in patients who underwent the procedure and 0.9 (95% CI: 0.8–0.9) in patients who did not (Table 4).

Selected non-GI cancers

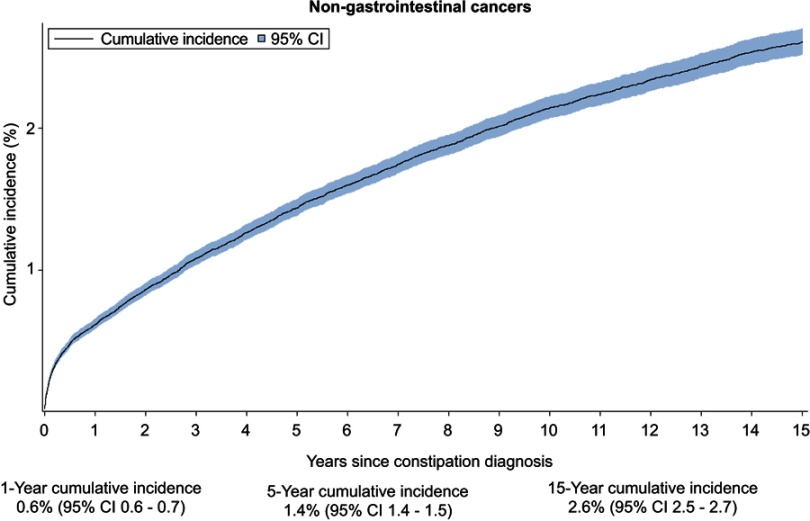

The cumulative incidence of selected non-GI cancers was 0.6% after 1 year of follow-up and 2.6% after 15 years of follow-up (Figure 2). During the first year of follow-up, the risk of ovarian cancer was most prominently increased (SIR =7.3, 95% CI: 6.3–8.4). The SIR for hormone-related cancers overall was 2.1 (95% CI: 2.0–2.3) during the first year of follow-up and 1.0 (95% CI: 0.9–1.0) thereafter. Corresponding estimates for lymphomas were 3.4 (95% CI: 3.0–3.9) and 1.1 (95% CI: 1.0–1.2) (Table 2). Short- and long-term risk estimates of non-GI cancers were robust in strata of sex, age at constipation diagnosis, type of hospital contact, calendar period, and level of comorbidity (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of selected non-gastrointestinal cancers in patients with a hospital-based diagnosis of constipation.a

Notes: aSelected non-gastrointestinal cancers included hormone-related cancers and lymphoma in patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation in Denmark, 1978–2013, accounting for death as a competing risk.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

Standardized incidence ratios for selected cancers in patients with a first-time hospital-based diagnosis of constipation in Denmark, 1978–2013

| 0–1 year after constipation diagnosis | 2–15 years after constipation diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer site | O | E | SIR (95% CI) | O | E | SIR (95% CI) |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 1851 | 367.2 | 5.0 (4.8–5.3) | 1658 | 1641.2 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| Colorectal cancers | 1172 | 227.0 | 5.2 (4.9–5.5) | 855 | 1022.6 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Colon (incl. rectosigmoid cancers) | 987 | 154.5 | 6.4 (6.0–6.8) | 679 | 700.1 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Rectum | 185 | 72.6 | 2.6 (2.2–3.0) | 176 | 322.5 | 0.6 (0.5–0.6) |

| Other gastrointestinal cancers | 679 | 140.2 | 4.8 (4.5–5.2) | 803 | 618.6 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) |

| Esophagus | 44 | 18.2 | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | 99 | 83.2 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Stomach | 138 | 38.0 | 3.6 (3.1–4.3) | 179 | 155.2 | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) |

| Small intestine | 38 | 3.7 | 10.2 (7.2–14) | 36 | 17.5 | 2.1 (1.4–2.9) |

| Anal canal | 9 | 4.0 | 2.3 (1.0–4.3) | 29 | 20.7 | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) |

| Liver | 64 | 15.2 | 4.2 (3.3–5.4) | 115 | 68.0 | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) |

| Gall bladder and biliary tract | 43 | 13.1 | 3.3 (2.4–4.4) | 67 | 57.7 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| Pancreas | 328 | 46.4 | 7.1 (6.3–7.9) | 271 | 210.0 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Other, poorly specified | 15 | 1.6 | 9.7 (5.4–16) | 7 | 6.4 | 1.1 (0.4–2.2) |

| Non-gastrointestinal cancers | ||||||

| Hormone-related cancers | 859 | 404.4 | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | 1919 | 1999.3 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

| Breast | 192 | 172.4 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 972 | 952.6 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| Corpus uteri | 48 | 33.5 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 137 | 175.5 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) |

| Ovary | 186 | 25.5 | 7.3 (6.3–8.4) | 104 | 133.9 | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) |

| Prostate | 420 | 164.6 | 2.6 (2.3–2.8) | 646 | 685.7 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| Testes | 5 | 2.8 | 1.8 (0.6–4.1) | 19 | 20.1 | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| Thyroid | 8 | 5.5 | 1.5 (0.6–2.9) | 41 | 31.6 | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) |

| Lymphomas | 203 | 59.3 | 3.4 (3.0–3.9) | 321 | 289.3 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

| Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma | 9 | 3.2 | 2.8 (1.3–5.3) | 23 | 21.0 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma | 194 | 56.1 | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 298 | 268.4 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; E, expected number of cases; O, observed number of cases; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis comparing results for primary vs secondary diagnoses of constipation yielded similar estimates and agreed with the main results for 2–15 years of follow-up. However, a slightly higher risk of GI cancers was found within the first year of follow-up for primary diagnosis compared with secondary diagnoses (Table 5).

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based cohort study, patients with a hospital-based diagnosis of constipation had higher risks of all GI cancers during the first year of follow-up, but only of GI cancers other than colorectal cancer thereafter. The increased short-term risk of colorectal cancer was driven mainly by colon cancer, whereas the risk of GI cancer other than colorectal cancer was driven primarily by cancer of the pancreas. Apart from a substantially increased risk of ovarian cancer, the risk of non-GI cancer was moderately increased during the first year of follow-up and approximated unity thereafter. The risk of cancer during the first year was higher in younger age groups. This observation was presumably attributed to very low absolute risk of cancer in younger age groups with correspondingly higher impact of constipation on relative risk of cancer. In stratifications by calendar year, we observed a tendency toward stronger associations between constipation and cancer in later time periods, which may be related to more aggressive work up of patients with constipation in more recent periods.

Our findings during the first year of follow-up could result from reverse causation, ie, cancers may cause constipation before the cancer itself becomes clinically overt. Hence, constipation could be a marker of prevalent occult cancers. This is consistent with the particularly increased short-term risks of colon, pancreas, and ovarian cancers observed in our study.

Unlike previous studies,17–27 we distinguished between short- and long-term risks of cancer because underlying mechanisms likely differ. Detection of prevalent occult cancers because of heightened diagnostic efforts likely drove the short-term risk. Incident cancers sharing risk factors with constipation likely underlie the long-term cancer risk.

Previous studies of the association between constipation and GI cancers yielded inconsistent results. In their meta-analysis of the association between constipation and colorectal cancer, Power et al35 found moderately reduced risk in cross-sectional surveys and no association in cohort studies. They reported an increased risk of cancer in case–control studies (odds ratio =1.68, 95% CI: 1.29–2.18), which, however, are prone to recall bias. Generally, the included studies varied greatly in terms of demographics, definition of constipation, methods, and follow-up time. The maximum follow-up time was 12 years in Dukas et al’s cohort study published in 2000.20 Their study found no association between constipation and colorectal cancer (relative risk =0.94, 95% CI: 0.69–1.28). It was based on 84,577 nurses but is likely generalizable to the general population. Most of the studies included in Power et al’s meta-analysis relied on self-reported constipation. Only one study used hospital-based diagnoses to identify patients;16 this case-cohort study was based on data from a US claims database and included 28,854 patients with chronic constipation and 86,562 patients without constipation matched by age, gender, and region of residence. The study yielded an adjusted incidence rate ratio of 1.59 (95% CI: 1.43–1.78) for colorectal cancer during 11 years of follow-up.16

Power et al35 suggested that constipation alone did not warrant lower GI diagnostic examinations, unless other findings were present such as dark red rectal bleeding or an abdominal mass, which are classical alarm symptoms of GI cancer.36 This conclusion was later reiterated by Neis et al.37 Subsequent studies also concluded that the indication for a lower endoscopy should not be based exclusively on a diagnosis of constipation.35,37,38

Several putative mechanisms may underlie the associations observed in our study. Decreased gut motility and associated increased transit time in patients with constipation is thought by some to increase risk of colorectal cancer due to prolonged duration of contact between the colonic mucosa and carcinogens in the stool.10 We found that constipation was associated with a significant but only slightly higher rate of some cancers outside the GI tract, as well as with GI cancers other than colorectal cancers. This could be explained by microbiota, which may contribute to cancer development or progression both in local and in distant locations. This mechanism includes activation and modulation of the immune system and damage to host DNA.14,15,39

The association between constipation and long-term risk of cancer may arise from shared risk factors that cause constipation long before clinically detectable cancer. This mechanism in part may drive the moderate, but consistently increased, long-term risk of GI cancers other than colorectal cancer. Such risk factors could include smoking or excessive alcohol intake, which may explain our finding of increased long-term risk of smoking- and alcohol-related cancers, including cancers of the stomach, pancreas, and liver.

The strengths of our study include the population-based cohort design and a setting within the unified Danish health care system, which provides all residents with free and equal access. This minimizes the risk of selection bias stemming from selective inclusion of specific hospitals, health insurance systems, or patients with differing income levels. In addition, our study was based on prospectively gathered data, eliminating recall bias. Although mandatory reporting to the DCR was first implemented in 1987, cancer diagnoses have high accuracy and completeness in the DCR, with 89% of the tumors verified morphologically.40 Use of administrative registries allowed us to include all patients diagnosed with constipation.

A concern is that no previous study has validated the constipation diagnosis in the DNPR. However, we expect that this diagnosis has a high positive predictive value since hospital contact for constipation requires a referral from a primary care physician and because restricting to primary diagnoses of constipation did not change the results. Any misclassification of the constipation diagnosis would likely be non-differential and bias our results towards the null. The completeness of the constipation registration may be hampered by registration of outpatient visits only from 1995 onwards. Another potential limitation is that primary care physicians may be more likely to refer individuals with constipation to the hospital if they suspect constipation is related to cancer. This could partly explain the association with cancer.

Only a minority of people with constipation seeks medical care. They likely represent the most severe cases of constipation. This implies high positive predictive value of the diagnosis, but also that our results may not be generalizable to milder cases of constipation. Furthermore, the date that constipation is diagnosed may occur several years after constipation onset, suggesting that our short-term estimates may include some cases of long-term exposure to constipation.

Conclusion

Patients with a diagnosis of constipation had elevated risks of colorectal and other GI cancers during the first year of follow-up, especially colon and pancreas cancers. Thereafter, the risk remained increased only for GI cancers other than colorectal cancer. The risk of non-GI cancers was moderately increased only in the short term, especially for ovarian cancer. After the first year of follow-up, the risk of these cancers was comparable to those in the general population. The potential to herald a clinically silent, but preexisting, cancer merits increased attention to symptoms or signs pointing to a potential cancer when patients present with constipation, especially when no obvious provoking factors are present and when other alarm symptoms are present (eg, dark red rectal bleeding or an abdominal mass). It remains unknown whether patients with constipation may accrue prognostic benefit from a formal screening program to detect cancers at an earlier stage. However, based on our findings, opportunistic screening focused on cancer-related symptoms and signs during diagnostic workup for constipation seems prudent.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wright PS, Thomas SL. Constipation and diarrhea: the neglected symptoms. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1995;11:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME. Epidemiology of constipation in europe and oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:5-230X-8-5. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE. Constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:709–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in north america: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellini M, Gambaccini D, Usai-Satta P, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation: fact and fiction. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11362–11370. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews CN, Storr M. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(Suppl. B):16B–21B. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbaan D, Marinus J, Visser M, van Rooden SM, Stiggelbout AM, van Hilten JJ. Patient-reported autonomic symptoms in parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;69:333–341. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266593.50534.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempler P, Amarenco G, Freeman R, et al. Management strategies for gastrointestinal, erectile, bladder, and sudomotor dysfunction in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:665–677. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkitt DP. Epidemiology of cancer of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1971;1993(36):1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajagopala SV, Vashee S, Oldfield LM, et al. The human microbiome and cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2017;10:226–234. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardbower DM, de Sablet T, Chaturvedi R, Wilson KT. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress: the smoking gun for helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer? Gut Microbes. 2013;4:475–481. doi: 10.4161/gmic.25583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett WS. Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015;348:80–86. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwabe RF, Jobin C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:800–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc3610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerin A, Mody R, Fok B, et al. Risk of developing colorectal cancer and benign colorectal neoplasm in patients with chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:83–92. doi: 10.1111/apt.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Citronberg J, Kantor ED, Potter JD, White E, A prospective study of the effect of bowel movement frequency, constipation, and laxative use on colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1640–1649. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Nakaya N, Kurashima K, Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, Tsuji I. Constipation, laxative use and risk of colorectal cancer: the miyagi cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2109–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons CC, Schouten LJ, Weijenberg MP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Bowel movement and constipation frequencies and the risk of colorectal cancer among men in the netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1404–1414. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dukas L, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS, Rosner B, Giovannucci EL. Prospective study of bowel movement, laxative use, and risk of colorectal cancer among women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tashiro N, Budhathoki S, Ohnaka K, et al. Constipation and colorectal cancer risk: the fukuoka colorectal cancer study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2025–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs EJ, White E. Constipation, laxative use, and colon cancer among middle-aged adults. Epidemiology. 1998;9:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts MC, Millikan RC, Galanko JA, Martin C, Sandler RS. Constipation, laxative use, and colon cancer in a north carolina population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yagyu K, Lin Y, Obata Y, et al. Bowel movement frequency, medical history and the risk of gallbladder cancer death: a cohort study in japan. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strom BL, Soloway RD, Rios-Dalenz JL, et al. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer. an international collaborative case-control study. Cancer. 1995;76:1747–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Micozzi MS, Carter CL, Albanes D, Taylor PR, Licitra LM. Bowel function and breast cancer in US women. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:73–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004;291:2705–2712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:541–549. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frank L. Epidemiology. when an entire country is a cohort. Science. 2000;287:2398–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storm HH, Michelsen EV, Clemmensen IH, Pihl J. The danish cancer registry–history, content, quality and use. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundhedsstyrelsen. Det moderniserede Cancerregister - metode og kvalitet. København; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, Auerbach AD. A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1229–1235. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II–the design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;2(82):1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Power AM, Talley NJ, Ford AC. Association between constipation and colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:894–903 quiz 904. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford AC, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Cc R, Nj T, Nb V, Moayyedi P. Diagnostic utility of alarm features for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2008;57:1545–1553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neis B, Nguyen D, Arora A, Kane S. The role of diagnostic colonoscopy in constipation: a quality improvement project. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1930. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pepin C, Ladabaum U. The yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a veterans administration medical center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen GY, Shaw MH, Redondo G, Nunez G. The innate immune receptor Nod1 protects the intestine from inflammation-induced tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10060–10067. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gjerstorff ML. The danish cancer registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:42–45. doi: 10.1177/1403494810393562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]