Abstract

A case of a 71-year-old man with femoral and tibial osteolysis and severe metallosis of the knee, resulting from abrasive wears of the metal components of a unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, that leaded to the rupture of the femoral component of the prosthesis is reported. An unicompartmental prosthesis, in a varus knee, was implanted in 2007. In March 2017, the patient felt that his knee was becoming increasingly unstable with pain and increasing disability. At clinical evaluation there was an effusion, 110° of flexion and – 10° of extension and a slight instability at the varus/valgus stress tests. BMI was 35. In a CT scan performed in June 2017 no signs of alteration were evident, but an X-Ray performed in January 2018 showed a rupture of the femoral component. A revision surgery was performed in February 2018. At the time of revision surgery, the synovitis and the metallosis were evident. A cemented total knee arthroplasty was performed. Samples of the fluid and surface did not show any bacterial growth. Histological examination confirmed the presence of a massive metallosis. The patient had a satisfactory rehabilitation. According to the literature, metallosis and rupture of the prosthetic components due to polyethylene wear after UKA is a common complication. In our case report the elevated BMI and varus knee accelerated the wear of the polyethylene. The aim of this case report is to enhance how an appropriate diagnosis (clinical and radiographic) and early treatment can lead to a successful result. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: metallosis, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, prosthetic rupture, metal debris, polyethylene wear

Introduction

Metallosis, a serious complication in knee arthroplasty, is a term used to describe the infiltration of metallic wear debris into the periprosthetic structures, including soft tissues and bone (1-3).

We report a case of massive wear of the polyethylene (PE) insert of a unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) which produced metal-on-metal abrasion between the femoral component and the metal tibial component, leading to the generation of metallic debris in the periprosthetic soft tissue and bone and to the rupture of the femoral component of the implant.

Case report

A 71-year-old man with osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the left knee (varus knee) received a primary cemented UKA without complications in 2007. His postoperative course was uneventful until March 2017, when he felt that his knee was becoming increasingly unstable, making frequent clicking noises with pain and increasing disability. Since his symptoms were getting worse, the patient came for a clinical assessment in February 2018. At that time, he had severe pain, swelling and an irritating feeling of ‘metal on metal’ when the knee was moved. At the clinical evaluation, there was an effusion, but there weren’t any other signs of infection (there wasn’t any redness and the temperature was similar to the other knee), the range of motion (ROM) was limited (110° of flexion and – 10° of extension) by the swelling and the pain and there was a slight instability at the varus/valgus stress tests. Regarding the general examination, there wasn’t anything to report besides a BMI of 35. The patient never had any fever. Blood tests were performed: complete blood count and differential leucocyte count, VES and PCR; the results of these were normal.

Since there were no local or systemic signs of infection, an aspiration was not performed.

In a CT scan performed in June 2017 (Fig. 1) no signs of alteration were evident, but an X-Ray performed in January 2018 (Fig. 2) showed a rupture in the UKA femoral component.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the UKA

Figure 2.

XR in LL projection. The white arrow indicates the rupture of the femoral component

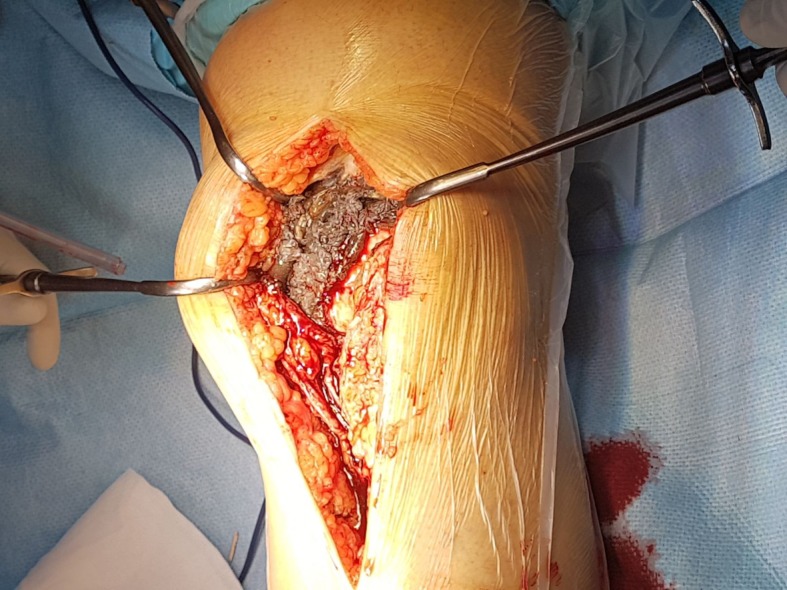

Revision surgery was performed at the end of February 2018. At the time of revision surgery, we noticed a very clear synovitis associated with a massive metallosis. The tibial component was well fixed while the femoral component was broken (Fig. 3-4).

Figure 3.

At the exposure of the articular cavity the metallosis and the synovitis were clear

Figure 4.

Intraoperative view of the broken femoral component and the wear of the polyethylene insert

There was a severe wear of the polyethylene tibial insert (Fig. 5) that caused a minor friction between the femoral component and tibial metal surface with a huge abrasion of the metal femoral component. The periprosthetic tissue affected by the metallic debris was cleaned up and several swab samples were taken from the articular structures. Then a cemented medial pivot total knee arthroplasty was performed (revision Advance, MicroPort®) (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Tibial and broken femoral component of the prosthesis

Figure 6.

Fluoroscopic image of the revision total knee arthroplasty

Bacteriological samples of the fluid and surfaces, taken during the surgery from the joint, did not show any growth. Histological examination confirmed the presence of a massive metallosis with a large amount of opaque pigment in histiocytic cells.

The patient had a satisfactory rehabilitation from the revision surgery. After two months, the range of motion was optimal (flexion 130° and extension 0°), the knee was stable and the patient was able to walk without any support.

Discussion

Common complications reported after performing UKA include: unclear pain, rupture of the medial or lateral collateral ligaments, dislocation of the polyethylene bearing, dissociation of the prosthesis components, degenerative changes in the opposite component and fracture of the medial proximal tibia (4-6).

Previous literature reported that failure of UKAs can be caused by: aseptic loosening of the femoral or tibial component, dislocation or instability of the prosthesis, malalignment of the prosthesis, deep infection, periprosthetic fracture, abrasion of the polyethylene liner and the progression of arthritis (7, 8). Among these, the main causes of UKA failure are: aseptic loosening, infection, patellofemoral pain, deterioration in the opposite compartment and polyethylene tibial insert wear (9-12).

More than half of the failures of UKA are due to polyethylene wear. Potential factors that can play a role in this complication include: time in situ, high localized contact stresses resulting from lack of congruency due to the geometry of the articulating surfaces, increased freedom of rotation, conservative resection of the bone, elevated BMI of the patient (13).

A metallosis permeating the periprosthetic soft tissue can be easily identified; in our case the metallosis was so severe that it could be seen radiographically and this situation should have alerted the orthopaedic surgeon to the urgent need of a revision surgery. Early revision seemed to be the best solution to prevent progressive joint destruction. Moreover, some authors recommend, in case of metallosis, a complete removal of metal wear particles in order to avoid possible immunological reactions, as well as periprosthetic osteolysis following the release of bone resorbing cytokines (14).

From a pathophysiological point of view, three mechanisms can be involved in the development of a chronic inflammatory arthritis by metal debris following a joint replacement. These mechanisms include metal hypersensitivity, direct toxic effect of the ionic metal particles and particle induced synovitis.

The presence of microscopic debris particles in the soft tissues induces a foreign body inflammatory reaction with a histiocytic infiltrate and multinucleated giant cells. Inflammatory cells infiltrate the synovium and causes synovial hyperplasia, giving the histopathologic evidence of black material in the synovium. This is usually associated with an acutely painful effusion.

The attempt to encapsulate the immunogen agents results in a fibrotic response due to the inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1, released by histocytes that engulf the metallic particles (15). These cytokines may cause the periprosthetic osteolysis associated with implant loosening.

Conclusions and clinical message

According to the literature, metallosis and rupture of the prosthetic components due to polyethylene wear after UKA can be an uncommon severe complication leading to a significant functional impairment. Orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of the pertinent clinical and radiographic signs and be prepared to perform an extensive revision surgery to restore joint function. As seen in this case of severe chronic metallosis, where our patient demonstrated risk factors for the accelerated wear of the PE (elevated BMI and varus knee), an appropriate diagnosis (clinical and radiographic) and an early treatment can lead to a successful result.

References

- 1.Hart R, Janecek M, Bucek B. Case report of extensive metallosis in extra-articular tissues after unicompartmental knee joint replacement. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2003;70:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottaviani G, Catagni M.A, Matturri L. Massive metallosis due to metal-on-metal impingement in substitutive long-stemmed knee prosthesis. Histopathology. 2005;46:237–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicente Sanchis-Alfonso. Severe metallosis after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji , et al. Complication of medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 2014;6:365–72. doi: 10.4055/cios.2014.6.4.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmor L. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: ten to 13 year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koskinen E, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Comparison of survival and cost-effectiveness between unicondylar arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis: a follow-up study of 50,493 knee replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(4):499–507. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, Faris PM, Meneghini RM. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(2):159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Failure mechanisms after unicompartmental and tricompartmental primary knee replacement with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(3):519–25. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartley RE, Stulberg SD, Robb WJ, Sweeney HJ. Polyethylene wear in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen OM, Christiansen TG, Johansen T. Polyethylene failure in a PCA unicompartmental knee prosthesis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:578–579. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford R, Sabokbar A, Wulke A, Murray DW, Athanasou NA. Expansion of an osteoarthritic cyst associated with wear debris. A case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80-B:900–903. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b6.8905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engh GA, Dwyer KA, Hanes CK. Polyethylene wear of metal-backed tibial components in total and unicompartmental knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74-B:9–17. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mc Govern TF, Moskal JT. Radiographic evaluation of periprosthetic metallosis after total knee arthroplasty. J South Orthop Assoc. 2002;11:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolf O, Baumann B, Sterner T, Schutze N, Jakob F, Eulert J, Rader CP. Characterization of mode II-wear particles and cytokine response in a human macrophage-like cell culture. Biomed Tech. 2005;50:25–29. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2005.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Saffar N, Revel PA. Interleukin-1 production by activated macrophages surrounding loosened orthopaedic implants: a potential role in osteolysis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:309–16. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]