Abstract

Members of the Culex pipiens complex differ in physiological traits that facilitate their survival in diverse environments. Assortative mating within the complex occurs in some regions where autogenous (the ability to lay a batch of eggs without a blood meal) and anautogenous populations are sympatric, and differences in mating behaviors may be involved. For example, anautogenous populations mate in flight/swarms, while autogenous populations often mate at rest. Here, we characterized flight activity of males and found that anautogenous strain males were crepuscular, while autogenous strain males were crepuscular and nocturnal, with earlier activity onset times. We conducted quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping to explore the genetic basis of circadian chronotype (crepuscular vs. crepuscular and nocturnal) and time of activity onset. One major-effect QTL was identified for chronotype, while 3 QTLs were identified for activity onset. The highest logarithm of the odds (LOD) score for the chronotype QTL coincides with a chromosome 3 marker that contains a 15-nucleotide indel within the coding region of the canonical clock gene, cryptochrome 2. Sequencing of this locus in 7 different strains showed that the C-terminus of CRY2 in the autogenous forms contain deletions not found in the anautogenous forms. Consequently, we monitored activity in constant darkness and found males from the anautogenous strain exhibited free running periods of ~24 h while those from the autogenous strain were ~22 h. This study provides novel insights into the genetic basis of flight behaviors that likely reflect adaptation to their distinct ecological niches.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, cryptochrome, Culex molestus, eurygamy, stenogamy, swarming

The Culex pipiens complex includes the most geographically widespread mosquitoes, worldwide, where they are important vectors of several human pathogens, including West Nile virus and parasites causing lymphatic filariasis (Vinogradova 2000; Fonseca et al. 2004; Kramer et al. 2008). Their remarkable success can be attributed to a combination of incidental, human-associated dissemination, and variation in several key physiological adaptations that promote their survival in diverse environments (Harbach et al. 1984; Vinogradova 2000; Harbach 2012). The number of species in the C. pipiens complex and their taxonomic status remain a subject of debate, with several factors making this group a challenge to resolve (Harbach et al. 1984; Harbach 2012; Nelms et al. 2013). They are morphologically similar; genetic introgression occurs in many, but not all areas where their ranges overlap; and they differ in physiological traits that confer a selective advantage in their ecological niche (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of the physiological and behavioral traits associated with the 2 most pervasive species in the C. pipiens complex of mosquitoes. TR.q (Trinidad), JHB.q (Johannesburg), IN.p (Indianapolis), SB.p (South Bend), SK.m (Shinkura), CH.m (Chicago), and NY.m (New York). Note: only TR.q, JHB.q, SK.m, and CH.m were characterized for activity behaviors.

Here, we focus on the 2 most pervasive species, Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) and Culex pipiens (L.), the southern and northern house mosquitoes, respectively. Culex quinquefasciatus inhabit tropical to warm temperate regions, while C. pipiens inhabit temperate to warm temperate regions (Mattingly et al. 1951; Barr 1967; Vinogradova 2000). Despite their taxonomic status, they hybridize where their ranges overlap, and their progeny are fertile (Mattingly et al. 1951; Barr 1967; Mattingly 1967; Vinogradova 2000). Culex pipiens sensu stricto can be divided into biotypes or “forms” based on physiological differences, where female C. pipiens form pipiens require a blood meal for egg development (anautogenous), and C. pipiens f. molestus lay a first batch of eggs without taking a blood meal (autogeny)—a trait thought to be associated with adaptation to underground environs where temperatures are moderate and blood sources are rare or nonexistent (Spielman 1964).

Variation in several behaviors appears to be associated with species and/or form. Among these are mating behaviors and diel flight activity. Culex quinquefasciatus and C. pipiens f. molestus readily mate in small cages (stenogamy), while C. pipiens f. pipiens generally require larger cages (eurygamy) (Vinogradova 2000). Though, C. quinquefasciatus and C. pipiens f. pipiens initiate mating in flight and in male swarms, C. pipiens f. pipiens requires more space for successful copulation (Roth 1948; Gibson 1985; Vinogradova 2000). Conversely, C. pipiens f. molestus mate at rest (Clements 1999; Vinogradova 2000), where males from autogenous strains are often observed flying to and attempting to mate with females resting on the sides of the cage.

A recent study on the mating behavior of C. pipiens f. pipiens and C. pipiens f. molestus observed a series of 5 distinct behaviors leading to copulation: tapping, mounting, co-flying, ventral-to-ventral copulation, and tail-to-tail copulation (Kim et al. 2018). It was observed that females often rejected males of the opposite form following pre-copulatory tapping behavior, wherein the male taps the female leg. These findings suggest an important role for chemical communication in mate recognition, likely in the form of contact pheromones such as cuticular hydrocarbons (Kim et al. 2018).

Circadian studies of C. pipiens forms that mate by swarming showed that males were largely crepuscular, while C. pipiens f. molestus males were both crepuscular and nocturnal (Chiba et al. 1981; Shinkawa et al. 1994). Prior to insemination, anautogenous females exhibit greater crepuscular activity, similar to males from anautogenous strains (Jones and Gubbins 1979; Chiba et al. 1992). Following insemination, anautogenous females shift their peaks of activity from dusk and dawn to scotophase (dark), while some autogenous females became diurnal. A male accessory gland pheromone transferred to the female during insemination was shown to cause this shift in flight activity in female C. quinquefasciatus (Jones and Gubbins 1979). These studies demonstrate the importance of flight activity in the mating behavior of mosquitoes by revealing a physiological mechanism that effectively synchronizes male and virgin female activity.

The presence of interspecies hybrids in nature and the ease at which viable crosses can be achieved in the laboratory suggest a lack of morphological and postzygotic mating barriers. However, the lower than expected frequency of interspecies hybrids and asymmetric introgression in some areas of sympatry suggest the presence of behavioral and/or ecological barriers to gene flow (Spielman 1967; Fonseca et al. 2009; Gomes et al. 2009). In South Africa, a region where C. quinquefasciatus and C. pipiens f. pipiens are sympatric, no evidence of genetic introgression was found (Jupp 1978; Cornel et al. 2003), yet hybridization occurs where their ranges overlap in North and South America, and East Asia (Mattingly 1951; Barr 1967; Kothera et al. 2009).

Studies on sympatric populations of C. pipiens f. pipiens and C. pipiens f. molestus in North America revealed lower than expected frequencies of interspecies hybrids under the assumption of random mating (Spielman 1964; Kothera et al. 2010), yet no barriers to gene flow were evident among populations in Egypt and Israel (Villani et al. 1986; Nudelman et al. 1988; Farid et al. 1991). Further, population studies have demonstrated that C. pipiens f. molestus is relatively distinct from aboveground C. pipiens f. pipiens in Europe, Asia, and Australia (Byrne and Nichols 1999; Fonseca et al. 2004).

Though spatial differences undoubtedly contribute to the population structure in some areas, temporal differences in mating behaviors could be involved and have been proposed to form a prezygotic barrier to gene flow between sympatric mosquito populations (Jones et al. 1974; Charlwood and Jones 1979; Manoukis et al. 2009; Rund et al. 2012). For example, Rund et al. (2012) noted that, in the laboratory, the time of peak male flight activity was 4.1 min earlier in one reproductively isolated incipient Anopheles gambiae mosquito complex form than the other form. In the field using video recordings, a similar study revealed more than a 9-min difference in onset times between males of the 2 forms (Sawadogo et al. 2013). When they swarmed over the same visual marker, the earlier form began and ended swarming earlier than the later form (Sawadogo et al. 2013). Observations of the closely related members of the An. gambiae complex—An. gambiae, An. funestus, An. melas, and An. merus—also revealed interspecies differences in time of activity onsets in males that were 4.2, 11.8, 9.2, and 29.4 min, respectively, after lights were turned off (Jones et al. 1974).

Due to their role in vertebrate host seeking and pathogen transmission, most studies on mosquito flight behavior have focused on females. However, a comprehensive understanding of mosquito reproductive biology cannot be achieved without considering male behavior. Here, we explored the genetic basis of behaviors associated with mating system differences in C. pipiens sensu lato (s.l.) by characterizing flight activity of males from autogenous (mate at rest) and anautogenous (mate in swarms) strains and performing quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis on the observed differences in chronotype (crepuscular vs. crepuscular and nocturnal activity) and time of activity onset.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito Strains

The symbols for the laboratory strains used in the study are suffixed with an m, p, or q to indicate C. pipiens f. molestus, C. pipiens f. pipiens, or C. quinquefasciatus, respectively. Two strains of C. pipiens s.l. were used for QTL analysis (Figure 1). The Shinkura (SK.m) strain was established in 1998 from a single C. pipiens f. molestus autogenous female collected in Tokushima, Japan. SK.m exhibits behaviors reported for other autogenous populations whereby mating takes place at rest and is not confined to dusk and dawn (Clements 1999; Vinogradova 2000). A C. quinquefasciatus laboratory strain (TR.q) established from field isolates collected in Trinidad in 2010 was used as the anautogenous strain. At the time of the study, TR.q had been maintained for ~26 generations and had retained behaviors typical of natural, anautogenous populations, such as mating in flight and blood feeding only during scotophase (nighttime).

We also monitored flight activity of males from another anautogenous C. quinquefasciatus (Johannesburg) and autogenous C. pipiens f. molestus (Chicago) strain to determine whether they exhibited similar flight behaviors. Johannesburg (JHB.q) was the strain used in whole genome sequencing of C. quinquefasciatus (Arensburger et al. 2010) and was established from field isolates collected in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2000 (Cornel et al. 2003). Chicago (CH.m) was established in 2009 from an underground, autogenous population in the greater Chicago area (Mutebi and Savage 2009). PCR assays to distinguish C. pipiens from C. quinquefasciatus (Aspen and Savage 2003) and C. pipiens f. molestus from C. pipiens f. pipiens (Bahnck and Fonseca 2006) were previously conducted (Fritz et al. 2014; Sullivan et al. 2014) and support our species/form designations. Mosquitoes were housed in 30- × 20- × 20-cm cages at 26 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% RH with a photoperiod of 16 h:8 h light:dark (LD) plus a 30-min dusk/dawn transition. Mosquitoes were provided 5% sucrose solution ad libitum. SK.m and CH.m were maintained without blood meals while JHB.q and TR.q were provided anesthetized rats for blood feeding.

Crossing Experiments

The F1 intercross mapping population was generated by mating a single C. quinquefasciatus (TR.q) male with a C. pipiens f. molestus (SK.m) female, and F1 progeny were “intercrossed” by mating 1 male and 2 females from the same egg raft (i.e., siblings). F2 progeny (males) from 2 egg rafts (64 + 31) were used to increase the number of individuals for linkage mapping and QTL analysis (see Supplementary Figure S1 for illustration of crossing strategy). A second cross, as described above, was later made to characterize the activity patterns of the F1 progeny. Cages and environmental conditions for mating were as reported for colony maintenance.

Activity Monitoring and Phenotype Analysis

To characterize flight activity of males from the parental strains (TR.q and SK.m), F1 and F2 progeny, as well as JHB.q and CH.m, we monitored activity using the Locomotor Activity Monitor 25 (LAM 25) system (TriKinetics, Waltham, MA) as described previously (Rund et al. 2012). Individual mosquitoes, 3–5 days post-eclosion, were placed in 25- × 150-mm clear glass test tubes with access to 5% sucrose solution ad libitum. Activity was monitored at 26 ± 1 °C and 80 ± 5% RH. Two light regimes were used: 16 h:8 h LD with 1-h dawn and dusk transitions, and constant dark:dark (DD).

Chronotype was scored using the mean number of activity bouts per day, over 4 days, outside the dusk/dawn transitions; therefore, a lower score represented the crepuscular phenotype while a higher score represented the crepuscular and nocturnal phenotype. We defined a bout as any flight activity (recorded by the LAM 25 unit as infrared beam breaks) separated by more than 5 min from another bout of activity.

Activity onsets and free running period lengths were measured in ClockLab (Actimetrics) by fitting a line to onset of nightly activity as a phase marker. Analysis in DD was conducted over 7 days following 5 days in LD, and only with TR.q and SK.m males. Statistical inferences were made using the Wilcoxon rank sum test in the MASS package (Venables and Ripley 2002) in the R statistical environment.

Genotyping and Sequencing

DNA was extracted from individual mosquitoes using a rapid NaOH method (Rudbeck and Dissing 1998), and genotyping was performed using 35 microsatellite markers described previously (Hickner et al. 2010, 2013), plus 3 novel markers: C11TGT1, C111GGA1, and C206GCT1 (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Marker names correspond to the genomic scaffold where the microsatellite is located and the repeat motif, that is, C11TGT1 corresponds to TGT motif on scaffold 3.11 in the CpipJ2 assembly (Giraldo-Calderón et al. 2015). PCR was conducted in 25 μL reactions in 96-well PCR plates (Dot Scientific Inc., Burton, MI). Each reaction contained 1× Taq buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 9.0, 0.1% Triton X), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM dNTPs, 0.2 µM each primer, 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase, and ~20 ng of genomic DNA. All PCR reagents were prepared in-house.

Thermal cycling was performed using Mastercycler® thermocyclers (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation for 5 min at 94 °C followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 94 °C, annealing for 1 min at 60 °C (all primer pairs), extension for 2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Forward primers were synthesized with either 6-FAM®, HEX®, or NED® fluorophores. The F0 generation was screened with a panel of 51 microsatellite markers to identify polymorphic loci, and 38 fully informative markers (i.e., no alleles were shared between parental strains) spanning all 3 C. pipiens chromosomes (~579 Mbp) were used to genotype individuals in the F2 generation. Alleles were scored using the ABI PRISM 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and ROX 400HD size standard. GeneMapper v.4.0 software (Applied Biosystems) was used to call the alleles, with subsequent visual verification of all genotypes. Sequencing of the C1500CAG1 locus (IN.p, SB.p, JHB.q, and CH.m) and cry2 genes (TR.q and SK.m) was performed using the ABI 3730xl (Life Technologies) and BigDye® (Life Technologies) chemistry at the University of Notre Dame Genomics Core Facility. The cry2 genes were sequenced from cDNA synthesized using Superscript II and oligo(dT)12–18 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The C1500CAG1 locus for the New York C. pipiens f. molestus strain (NY.m) was obtained by BLASTn analysis of sequence read archive SRX870602 from transcriptome analysis by Price and Fonseca (2015). Sequences were aligned using MultAlin (Corpet 1988).

Genetic Mapping and QTL Analysis

Multipoint linkage analysis was performed using the regression mapping algorithm and Kosambi function in JoinMap® 4.1 (Van Ooijen 2006). QTL analysis of chronotype and activity onset was performed with the R/QTL program using the nonparametric model (Broman et al. 2003). Ninety-five F2 progeny were used for linkage mapping, while 94 were used for QTL analysis of chronotype and activity onset due to the removal of one individual that died during activity monitoring (see Supplementary Figure S1 for additional details of mating strategy). The data were permuted 1000 times to determine critical logarithm of the odds (LOD) scores. Confidence intervals for individual QTL were estimated as Bayes 95% credible intervals. The estimated phenotypic variance (EV) was estimated from the difference in LOD scores as: EV = 1–10−(2/n)LOD (Broman and Sen 2009). Additive (a) and dominance (d) effects of individual QTL were calculated relative to alleles at the marker locus closest to the predicted QTL as outlined in Edwards et al. (1987). Mode of gene action was determined as the absolute value of d/a, where additive = 0–0.20, partial dominance = 0.21–0.80, dominance = 0.81–1.20, and overdominance >1.20 (Stuber et al. 1987; Babu et al. 2006).

Results

Diel Flight Activity

Activity monitoring of 41 TR.q and 36 SK.m males in LD (16:8) revealed TR.q were active almost exclusively during the dusk and dawn transitions, while SK.m were active during the dusk and dawn transitions but also during scotophase, and flight activity of males from CH.m and JHB.q were similar to those from SK.m and TR.q, respectively (Figure 2), while F1 males from a second cross exhibited activity patterns that were intermediate between SK.m and TR.q (Figure 3a). The mean number of activity bouts per day was used to score chronotype (crepuscular vs. crepuscular and nocturnal), which was highly effective in distinguishing representatives from the parent strains (P = 4.341e-14). The mean number of activity bouts per day ranged from 0 to 1.75 in TR.q and 5.5 to 21.75 in SK.m (Figure 3a). The number of activity bouts of F1 progeny from a second cross (n = 6) was intermediate to SK.m-like, ranging from 2.0 to 7.0 (Figure 3a). The number of bouts in the F2 males (n = 94) used for QTL analysis ranged from 0.25 to 13.75, with a distribution skewed toward fewer bouts per day (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 2.

Representative actograms of C. quinquefasciatus males from the (a) Trinidad and (c) Johannesburg strains (anautogenous), and C. pipiens f. molestus males from the (b) Shinkura and (d) Chicago strains (autogenous) illustrating the differences in chronotype (crepuscular vs. crepuscular and nocturnal) and activity onset time in LD (16:8). ZT12 was set to the beginning of the scotophase. Horizontal light/dark bars indicate light/dark cycle. Data were normalized within individuals.

Figure 3.

The proxy for chronotype was based on the mean number of activity bouts outside the dawn and dusk transitions. We defined a bout as any flight activity (recorded by the LAM 25 unit as infrared beam breaks) separated by more than 5 min from another bout of activity. (a) Mean activity bouts of males from TR.q (n = 36) and SK.m (n = 41), and F1 (n = 6) and F2 (n = 94) progeny. (b) The distribution of mean bouts per day in the F2 progeny. (c) Activity onset times of males from TR.q (n = 36) and SK.m (n = 41), and F1 (n = 6) and F2 (n = 94) progeny. ZT12 was set to the beginning of the scotophase. (d) The distribution of activity onset times in the F2 progeny. Labels on the x-axes represent intervals between the numbers, for example, the number of mean bouts between 0 and 0.999, 1, and 1.999, etc.

The onset of activity at dusk was later in TR.q than in SK.m (P = 6.127e-14), with a difference in the median onset of activity of 31 min (Figure 3c). Activity onset in 6 F1 progeny was intermediate between TR.q and SK.m, while the F2 (n = 94) progeny were mostly TR.q-like with a skewed unimodal distribution toward a later activity onset (Figure 3c,d).

Linkage Mapping

A genetic map was estimated using 95 F2 progeny and 38 microsatellite markers covering 38 loci with broad distribution across the genome: 4 loci on chromosome 1 spanning 37.5 cM (Kosambi cM) for a mean interval size of 12.5 cM; 17 loci on chromosome 2 spanning 95.0 cM for a mean interval size of 5.9 cM; and 17 loci spanning 61.2 cM for a mean interval size of 3.8 cM (Figure 4a). The size of the linkage groups and the order of the markers were consistent with those previously reported in a composite linkage map (Hickner et al. 2013).

Figure 4.

(a) Linkage map (Kosambi cM) for F1 intercross progeny from mating a Shinkura strain (SK.m) female and a Trinidad strain (TR.q) male. Circles show the predicted QTL position and the bars represent the 95% Bayes confidence interval. The predicted position of 5 canonical clock genes based on Hickner et al. (2013) and the present study. (b) Likelihood ratio profiles for chronotype and time of activity onset. Dashed lines represent the experimentwise threshold value (P = 0.05) for identifying a QTL based on 1000 permutations. (c) Genotype-to-phenotype plots at the markers closest to the QTL for chronotype and time of activity onset. Error bars represent 1 SE from the mean.

Based on this linkage map and a composite map (Hickner et al. 2013), we were able to predict the chromosome location of 5 canonical clock genes (Figure 4a). Timeless (CPIJ007082) is on genome scaffold 3.139 (C139CT1) on chromosome 2, while the remaining 4 are on chromosome 3, where clock (CPIJ002146) is on scaffold 3.21 (C21TTG1), cryptochrome 1 (CPIJ009455) is on scaffold 3.247 (C247CAG1), period (CPIJ007193) is on scaffold 3.163 (C163CAG1), and cryptochrome 2 (CPIJ018859) is on scaffold 3.1500 (C1500CAG1). Individual marker details are included in Supplementary Table S1.

QTL Analysis

A summary of QTL mapping of chronotype and activity onset time is shown in Table 1. A single major-effect QTL on chromosome 3 was identified for chronotype based on a LOD threshold of P <0.05 (Figure 4) that explains 36.4% of the observed variance (Table 1). The 95% Bayes interval (BI) spans an 8-cM region (48–56 cM) near the end of chromosome 3 (Figure 4a). Estimates of additive and dominance effects, and the phenotype-to-genotype plot at the marker closest to the QTL, suggest that the mode of action is additive (Table 1, Figure 4c). The highest LOD for the chronotype QTL coincides with C1500CAG1, a microsatellite locus containing CAG repeats within the 3′ coding region of cry2.

Table 1.

Summary of QTLs for the observed differences in chronotype and activity onset time between males from autogenous and anautogenous strains of C. pipiens s.l.

| Phenotype | Chr. | Position | LOD (P) | Closest marker | EV | a | d | Action | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronotype | 3 | 53.9 | 9.24 (<0.001) | C1500CAG1 | 36.4 | −2.43 | 0.047 | A | 0.02 |

| Activity onset | 1 | 11.0 | 2.89 (0.01) | C660GTG1 | 13.2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 2 | 52.0 | 2.70 (0.045) | C129CT1 | 12.4 | 0.057 | −0.055 | D | 1.04 | |

| 3 | 12.0 | 5.00 (<0.001) | C38AC1 | 21.7 | 0.105 | 0.016 | A | 0.15 |

EV, estimated phenotypic variance explained; Action, mode of action determined as d/a where additive (A) = 0.0–0.20, partial dominance (PD) = 0.21–0.80, dominance (D) = 0.81–1.20, and overdominance (OD) = >1.20 (after Stuber et al. 1987; Babu et al. 2006); Degree, d/a. n/a, not applicable.

Analysis of activity onset identified 3 QTLs, one on each of the 3 chromosomes (Table 1, Figure 4a,b). The chromosome 1 QTL explains 13.2% of the phenotypic variation and has a 95% BI that spans an 18-cM interval (5–23 cM). The phenotype-to-genotype plot suggests an additive effect with the TR.q alleles contributing to a later onset of activity (Figure 4c). Only 2 genotypes were present because we analyzed males, and this region has a low recombination rate due to its proximity to the sex determining locus. The chromosome 2 QTL explains 12.4% of the phenotypic variation and has a 95% BI that spans a 50-cM region (30–80 cM) across the middle of the chromosome. This QTL is different from the QTLs on chromosome 1 and 3 due to its opposite effect whereby the TR.q alleles are dominant for an earlier activity onset time (Figure 4c). The chromosome 3 QTL has a 95% BI spanning a 33 cM region at the opposite end of the chronotype QTL (Figure 4a). This QTL is additive and explains 21.7% of the phenotype variation (Table 1).

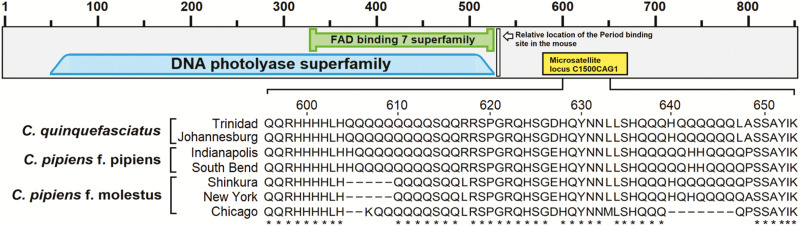

Because the C1500CAG1 coincides with the highest LOD for the circadian chronotype QTL, and the microsatellite polymorphism was in the coding region of cry2, we sequenced the locus in TR.q and JHB.q (C. quinquefasciatus), SK.m and CH.m (C. pipiens f. molestus), and South Bend and Indy (C. pipiens f. pipiens) (Figure 5) to determine if these indels were present in other strains (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, we mined SRAs (sequence read archives) in NCBI to obtain the C1500CAG1 locus in a New York isolate of C. pipiens f. molestus (Price and Fonseca 2015). All 3 C. pipiens f. molestus strains had deletions in at least one of 2 microsatellite regions within the C1500CAG1 locus containing CAG or CAA repeats that correspond to runs of glutamine (Q) (Figure 5), while C. quinquefasciatus and C. pipiens f. pipiens (swarm mating types) were similar to each other in that they lacked these deletions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A model of CRY2 showing the location of the predicted protein domains and the polymorphic microsatellite region in 7 members of the C. pipiens complex. The relative site of the PER interaction domain is from Ozber et al. (2010).

Free Running Period Length

The close association of cry2 with the QTL for chronotype, together with the differences in the C-terminus of the CRY2 protein, led us to evaluate TR.q and SK.m for strain-specific differences in the period length of their endogenous circadian clock. We monitored the activity of 48 TR.q males and 48 SK.m males over 7 days in DD to determine the length of their free running periods. Animals that died or ceased to move for a day or more during the assay (TR.q = 20, SK.m = 11) were excluded. Analysis revealed a considerable difference in their free running periods (P = 7.08e-12), with TR.q (n = 28) and SK.m (n = 37) males having mean period lengths of 24.26 and 22.08 h, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Representative actograms of males from the (a) Trinidad (C. quinquefasciatus) and (b) Shinkura (C. pipiens f. molestus) strains in DD (0:24) illustrating the differences in the length of their free running periods. Horizontal light/dark bars indicate light/dark cycle. Data were normalized within individuals. (c) Lengths of the free running periods of males from the Trinidad (n = 28) and Shinkura (n = 37) strains.

Discussion

The population structure of the C. pipiens complex of mosquitoes is largely determined by a number of physiological and behavioral adaptations that confer a selective advantage in their different ecological niches (Mattingly et al. 1951; Barr 1967; Harbach et al. 1984; Vinogradova 2000; Harbach 2012). Here, we characterized temporal properties of flight activity of males from autogenous and anautogenous strains to investigate behaviors which could be creating barriers to gene flow in some areas of sympatry. We then conducted QTL analysis to investigate the genetic basis of the observed variation in circadian chronotype and time of activity onset.

Males from both of our autogenous strains exhibited activity patterns that were consistent with another autogenous strain in which flight was not confined to dusk and dawn, but also occurred during scotophase (Shinkawa et al. 1994). Similarly, flight activity of males from 2 anautogenous strains were consistent with previous reports showing flight activity occurred primarily during the dusk and dawn transitions (Chiba et al. 1981).

The QTL for time of activity onset span large regions across all 3 chromosomes, thus precluding the identification of candidate genes underlying this trait. Despite the limited resolution, we are able to conclude that activity onset and circadian chronotype have different genetic underpinnings. In addition, the canonical clock genes period, cry1, cry2, timeless, and cycle do not contribute a noticeable effect to the observed variation in activity onset because they are not within the QTL Bayes’ confidence intervals.

In contrast to activity onset, a single, large-effect QTL was identified for circadian chronotype spanning only 8 cM. Though this is a relatively narrow region on chromosome 3, it is likely that a large number of genes reside in this interval. The exact number of genes is unknown because marker density was not high, and expanding to the closest markers increases the interval to 13.9 cM. Nevertheless, several lines of evidence make CRY2 a feasible candidate underlying the observed variation in circadian chronotype. First, the highest LOD score for the chronotype QTL corresponds with C1500CAG1. Second, the microsatellite polymorphism is within the coding region of a canonical clock gene. Third, 2 other C. pipiens molestus strains have a shorter CRY2 C-terminus, while CRY2 in aboveground, anautogenous C. pipiens f. pipiens and C. quinquefasciatus is longer. However, functional analysis, such as a genome editing strategy, is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Additional evidence for a role of CRY2 in the regulation of circadian chronotype was found in a study by Gentile et al. (2009) who conducted gene expression analysis on 8 canonical clock genes in females of the crepuscular and nocturnal C. quinquefasciatus and the diurnal Aedes aegypti. They found that the expression profiles of period, timeless, clock, cycle, vrille, par-domain-protein-1, and cry1 over a 24-h period were similar in both species. However, the rhythmic expression of cry2 was bimodal in A. aegypti, but unimodal (single distinct peak and trough) in C. quinquefasciatus.

Mosquitoes differ from Drosophila, with mosquitoes having 2 types of cryptochromes: a Drosophila-like photoreceptor CRY1 and a mammalian-like non-photoreceptor CRY2 (Zhu et al. 2005; Rubin et al. 2006; Yuan et al. 2007; Rund et al. 2011). A study in which An. gambiae cry2 was cloned into a D. melanogaster cell line demonstrated its function as a transcriptional repressor of CLK:CYC-activated transcription, just as it does in the mouse, Mus musculus (Zhu et al. 2005).

A model has thus been developed whereby mosquito CRY2 functions as a key element of the negative loop of the transcriptional–translational feedback mechanism that comprises the circadian clock. A circadian rhythm in cry2 expression is driven through the action of positive loop components CLK:CYC, acting on its gene promoter. CRY2 protein then associates with the PER:TIM dimer in the cytoplasm through an interaction between CRY2 and PER. CRY2 accesses the nucleus as part of the PER:TIM complex, wherein CRY2 associates with CLK:CYC to turn off its transactivation activity and repress transcription of core circadian clock components and other genes. This closes the ~24-h feedback loop. In contrast, CRY1 is activated by light, resulting in its binding to TIM in the cytoplasm, and facilitating TIM degradation. Since TIM is important for nuclear entry, this results in less PER and CRY2 accumulation in the nucleus, which in turn results in a phase shift of the circadian clock mechanism (Yuan et al. 2007; Rund et al. 2011; Zhan et al. 2011; Tomioka and Matsumoto 2015). It was demonstrated that substitution of only 2 amino acids (500 and 503 aa) in the C-terminus of the mouse CRY2 can completely abolish its interaction with the Period protein (Ozber et al. 2010). As we found length polymorphisms and amino acid substitutions in the CRY2 C-terminus (605–648 aa), it is possible that strain-specific differences in flight activity are due to differences in the interaction of CRY2 with Period.

The period gene in Drosophila provides an excellent example of microsatellite polymorphisms that confer genetic variation associated with adaptive behaviors. The D. melanogaster period gene encodes threonine–glycine (Thr–Gly) repeats (Costa et al. 1991) that vary in number from 14 to 24, and influences temperature compensation of the circadian clock (Sawyer et al. 1997). In Europe, alleles accounting for a large majority of the natural variants follow a latitudinal cline, where the (Thr–Gly)17 is prevalent in the south while (Thr–Gly)20 is prevalent in the north (Costa et al. 1992). Variation in the number of Thr–Gly repeats was also shown to influence courtship song in Drosophila (Wheeler et al. 1991), thus demonstrating the potential of clock genes to produce pleiotropic effects on mating behaviors that are not related to time of day.

Analysis in constant dark conditions revealed strain-specific differences in the endogenous free running period length of the clock, with TR.q having a period length slightly more than 24 h and SK.m having a period length ~22 h. It is possible that the earlier activity onset for the autogenous SK.m strain under entrained conditions reflects the short period length of its endogenous clock. It has been established in several organisms, including the mosquito, that the free running period impacts the timing of activity onset (Helfrich-Förster 2000; Toh et al. 2001; Duffy et al. 2011; Rund et al. 2012). For example, the ~10 min earlier activity onset observed in male versus female An. gambiae mosquitoes is correlated with a sex-specific ~10-min shorter period length (Rund et al. 2012). However, because we did not perform QTL analysis on length of the free running periods, evidence in support of this in Culex is lacking.

The observed differences in chronotype and activity onset likely reflect differences in their mating strategies, that is, mating in flight versus mating at rest. Adaptation to belowground environs would favor alleles that permit successful mating in the absence of a conspicuous dusk and dawn, which is an important cue in the synchronization of male and female activity in aboveground, anautogenous populations (Jones and Gubbins 1979; Chiba et al. 1992). At the same time these behavioral traits are being selected, alleles producing autogeny would also be favored. This adaptive process could involve a number of mechanisms that include pleiotropy, genetic hitchhiking, or strong selection at unlinked loci—or a combination of these. Once autogeny and the associated behaviors are established in a population, the different reproductive strategies would likely reduce gene flow if they became sympatric with aboveground, anautogenous populations. Where populations are panmictic, such as Egypt and Israel, these mating behaviors are likely less distinct. However, further analyses that include field isolates from panmictic populations are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

The persistent transmission of malaria in Africa, the recent spread of West Nile, dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses to non-endemic areas, and the paucity of vaccines against mosquito-borne pathogens, illustrate the need for more effective mosquito control strategies. The release of transgenic/sterilized mosquitoes has shown promise as a means to reduce vector populations (Benedict and Robinson 2003; Carvalho et al. 2015). However, a comprehensive understanding of mosquito activity and mating behaviors is essential to maximize the efficacy of genetic control strategies (Scott et al. 2008). Indeed, differences in mating time have been noted in a variety of agricultural pests between sterilized, lab-reared animals and their control-targeted wild populations (see Miyatake et al. 2002; Matsumoto et al. 2008). We here identified a putative genetic basis for chronological differences in the timing of a mosquito flight behaviors that likely reflect adaptation to their distinct ecological niches.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. RO1-AI079125-A1 to D.W.S.); National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01-GM087508 to G.E.D.); and the Eck Institute for Global Health (grant to G.E.D.). S.S.C.R. was funded by a Royal Society Newton International Fellowship (NF140517) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract no. HHSN272201400029C (VectorBase Bioinformatics Resource Center).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Yoshihito Chiba for graciously providing his insightful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Arensburger P, Megy K, Waterhouse RM, Abrudan J, Amedeo P, Antelo B, Bartholomay L, Bidwell S, Caler E, Camara F, et al. 2010. Sequencing of Culex quinquefasciatus establishes a platform for mosquito comparative genomics. Science. 330:86–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspen S, Savage HM. 2003. Polymerase chain reaction assay identifies North American members of the Culex pipiens complex based on nucleotide sequence differences in the acetylcholinesterase gene ACE.2. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 19:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu R, Nair SK, Kumar A, Rao HS, Verma P, Gahalain A, Singh IS, Gupta HS. 2006. Mapping QTLs for popping ability in a popcorn x flint corn cross. Theor Appl Genet. 112:1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahnck CM, Fonseca DM. 2006. Rapid assay to identify the two genetic forms of Culex (Culex) pipiens L. (Diptera: Culicidae) and hybrid populations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 75:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr AR. 1967. Occurrence and distribution of the Culex pipiens complex. Bull World Health Organ. 37:293–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MQ, Robinson AS. 2003. The first releases of transgenic mosquitoes: an argument for the sterile insect technique. Trends Parasitol. 19:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Sen S. 2009. A guide to QTL mapping with R/qtl. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. 2003. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 19:889–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne K, Nichols RA. 1999. Culex pipiens in London underground tunnels: differentiation between surface and subterranean populations. Heredity. 82:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho DO, McKemey AR, Garziera L, Lacroix R, Donnelly CA, Alphey L, Malavasi A, Capurro ML. 2015. Suppression of a field population of Aedes aegypti in Brazil by sustained release of transgenic male mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 9:e0003864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlwood JD, Jones MDR. 1979. Mating behaviour in the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae s.l. I. Close range and contact behavior. Physiol Entomol. 4:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Shinkawa Y, Yoshii M, Matsumoto A, Tomioka K, Takahashi SY. 1992. A comparative study on insemination dependency of circadian activity pattern in mosquitoes. Physiol Entomol. 17:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Yamakado C, Kubota M. 1981. Circadian activity of the mosquito Culex pipiens molestus in comparison with its subspecies Culex pipiens pallens. Int J Chronobiol. 7:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN. 1999. The biology of mosquitoes: sensory reception and behavior. Vol. 2 Wallingford (UK): CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Cornel AJ, McAbee RD, Rasgon J, Stanich MA, Scott TW, Coetzee M. 2003. Differences in extent of genetic introgression between sympatric Culex pipiens and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in California and South Africa. J Med Entomol. 40:36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:10881–10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa R, Peixoto AA, Barbujani G, Kyriacou CP. 1992. A latitudinal cline in a Drosophila clock gene. Proc Biol Sci. 250:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa R, Peixoto AA, Thackeray JR, Dalgleish R, Kyriacou CP. 1991. Length polymorphism in the threonine-glycine-encoding repeat region of the period gene in Drosophila. J Mol Evol. 32:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Cain SW, Chang AM, Phillips AJ, Münch MY, Gronfier C, Wyatt JK, Dijk DJ, Wright KP Jr, Czeisler CA. 2011. Sex difference in the near-24-hour intrinsic period of the human circadian timing system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108(Suppl. 3):15602–15608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MD, Stuber CW, Wendel JF. 1987. Molecular-marker-facilitated investigations of quantitative-trait loci in maize. I. Numbers, genomic distribution and types of gene action. Genetics. 116:113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid HA, Gad AM, Spielman A. 1991. Genetic similarity among Egyptian populations of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 28:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca DM, Keyghobadi N, Malcolm CA, Mehmet C, Schaffner F, Mogi M, Fleischer RC, Wilkerson RC. 2004. Emerging vectors in the Culex pipiens complex. Science. 303:1535–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca DM, Smith JL, Kim HC, Mogi M. 2009. Population genetics of the mosquito Culex pipiens pallens reveals sex-linked asymmetric introgression by Culex quinquefasciatus. Infect Genet Evol. 9:1197–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz ML, Walker ED, Yunker AJ, Dworkin I.. 2014. Daily blood feeding rhythms of laboratory-reared North American Culex pipiens. J Circadian Rhythms. 12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile C, Rivas GB, Meireles-Filho AC, Lima JB, Peixoto AA. 2009. Circadian expression of clock genes in two mosquito disease vectors: cry2 is different. J Biol Rhythms. 24:444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. 1985. Swarming behavior of the mosquito Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus: a quantitative analysis. Physiol Entomol. 10:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Calderón GI, Emrich SJ, MacCallum RM, Maslen G, Dialynas E, Topalis P, Ho N, Gesing S, Madey G, Collins FH, et al. ; VectorBase Consortium 2015. VectorBase: an updated bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vectors and other organisms related with human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:D707–D713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B, Sousa CA, Novo MT, Freitas FB, Alves R, Côrte-Real AR, Salgueiro P, Donnelly MJ, Almeida AP, Pinto J. 2009. Asymmetric introgression between sympatric molestus and pipiens forms of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Comporta region, Portugal. BMC Evol Biol. 9:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE. 2012. Culex pipiens: species versus species complex – taxonomic history and perspective. J Am Mosquito Contr. 28:10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE, Harrison BA, Gad AM. 1984. Culex (Culex) molestus Forskål (Diptera: Culicidae): neotype designation, description, variation, and taxonomic status. Proc Entomol Soc Wash. 86:521–542. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Förster C. 2000. Differential control of morning and evening components in the activity rhythm of Drosophila melanogaster–sex-specific differences suggest a different quality of activity. J Biol Rhythms. 15:135–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickner PV, Debruyn B, Lovin DD, Mori A, Behura SK, Pinger R, Severson DW. 2010. Genome-based microsatellite development in the Culex pipiens complex and comparative microsatellite frequency with Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. PLoS One. 5:e13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickner PV, Mori A, Chadee DD, Severson DW. 2013. Composite linkage map and enhanced genome map for Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes. J Hered. 104:649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MDR, Gubbins SJ. 1979. Modification of female circadian flight-activity by a male accessory gland pheromone in the mosquito, Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus. Physiol Entomol. 4:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Jones MDR, Gubbins SJ, Cubbin CM. 1974. Circadian flight activity in 4 sibling species of Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera, Culicidae). Bull Entomol Res. 64:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Jupp PG. 1978. Culex (Culex) pipiens pipiens Linnaeus and Culex (Culex) pipiens quinquefasciatus Say in South Africa morphological and reproductive evidence in favour of their status as two species. Mosq Syst. 10:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Trocke S, Sim C. 2018. Comparative studies of stenogamous behaviour in the mosquito Culex pipiens complex. Med Vet Entomol. 32:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothera L, Godsey M, Mutebi JP, Savage HM. 2010. A comparison of aboveground and belowground populations of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes in Chicago, Illinois, and New York City, New York, using microsatellites. J Med Entomol. 47:805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothera L, Zimmerman EM, Richards CM, Savage HM. 2009. Microsatellite characterization of subspecies and their hybrids in Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes along a north-south transect in the central United States. J Med Entomol. 46:236–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer LD, Styer LM, Ebel GD. 2008. A global perspective on the epidemiology of West Nile virus. Annu Rev Entomol. 53:61–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoukis NC, Diabate A, Abdoulaye A, Diallo M, Dao A, Yaro AS, Ribeiro JM, Lehmann T. 2009. Structure and dynamics of male swarms of Anopheles gambiae. J Med Entomol. 46:227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A, Ohta Y, Itoh TQ, Sanada-Morimura S, Matsuyama T, Fuchikawa T, Tanimura T, Miyatake T. 2008. Period gene of Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae) among strains with different mating times and sterile insect technique. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 101:1121–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly PF. 1967. The systematics of the Culex pipiens complex. Bull World Health Organ. 37:257–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly PF, Rozeboom LE, Knight KL, Laven H, Drummond FH, Christophers SR, Shute PG. 1951. The Culex pipiens complex. Trans Roy Ent Soc Lond. 102:331–382. [Google Scholar]

- Miyatake T, Matsumoto A, Matsuyama T, Ueda HR, Toyosato T, Tanimura T. 2002. The period gene and allochronic reproductive isolation in Bactrocera cucurbitae. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 269:2467–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutebi JP, Savage HM. 2009. Discovery of Culex pipiens pipiens form molestus in Chicago. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 25:500–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms BM, Kothera L, Thiemann T, Macedo PA, Savage HM, Reisen WK. 2013. Phenotypic variation among Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae) populations from the Sacramento Valley, California: horizontal and vertical transmission of West Nile virus, diapause potential, autogeny, and host selection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 89:1168–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman S, Galun R, Kitron U, Spielman A. 1988. Physiological characteristics of Culex pipiens in the Middle East. Med Vet Entomol. 2:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozber N, Baris I, Tatlici G, Gur I, Kilinc S, Unal EB, Kavakli IH. 2010. Identification of two amino acids in the C-terminal domain of mouse CRY2 essential for PER2 interaction. BMC Mol Biol. 11:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DC, Fonseca DM. 2015. Genetic divergence between populations of feral and domestic forms of a mosquito disease vector assessed by transcriptomics. PeerJ. 3:e807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth LM. 1948. A study of mosquito behavior. Am Midl Nat. 40:265–352. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin EB, Shemesh Y, Cohen M, Elgavish S, Robertson HM, Bloch G. 2006. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses reveal mammalian-like clockwork in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) and shed new light on the molecular evolution of the circadian clock. Genome Res. 16:1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudbeck L, Dissing J. 1998. Rapid, simple alkaline extraction of human genomic DNA from whole blood, buccal epithelial cells, semen and forensic stains for PCR. Biotechniques. 25:588–890, 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund SS, Hou TY, Ward SM, Collins FH, Duffield GE. 2011. Genome-wide profiling of diel and circadian gene expression in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:E421–E430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rund SS, Lee SJ, Bush BR, Duffield GE. 2012. Strain- and sex-specific differences in daily flight activity and the circadian clock of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. J Insect Physiol. 58:1609–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawadogo SP, Costantini C, Pennetier C, Diabaté A, Gibson G, Dabiré RK. 2013. Differences in timing of mating swarms in sympatric populations of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae s.s. (formerly An. gambiae M and S molecular forms) in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Parasit Vectors. 6:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer LA, Hennessy JM, Peixoto AA, Rosato E, Parkinson H, Costa R, Charalambos P. 1997. Natural variation in a Drosophila clock gene and temperature compensation. Science. 278:2117–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TW, Harrington LC, Knols BG, Takken W. 2008. Applications of mosquito ecology for successful insect transgenesis-based disease prevention programs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 627:151–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkawa Y, Takeda S, Tomioka K, Matsumoto A, Oda T, Chiba Y. 1994. Variability in circadian activity patterns within the Culex pipiens complex (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 31:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman A. 1967. Population structure in the Culex pipiens complex of mosquitos. Bull World Health Organ. 37:271–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber CW, Edwards MD, Wendel JF. 1987. Molecular marker facilitated investigations of quantitative trait loci in maize. II. Factors influencing yield and its component traits. Crop Sci. 27:639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GA, Liu C, Syed Z. 2014. Oviposition signals and their neuroethological correlates in the Culex pipiens complex. Infect Genet Evol. 28:735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, Eide EJ, Hinz WA, Virshup DM, Ptácek LJ, Fu YH. 2001. An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Science. 291:1040–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka K, Matsumoto A. 2015. Circadian molecular clockworks in non-model insects. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 7:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen JW. 2006. JoinMap 4, software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps in experimental populations. Wageningen (the Netherlands): Kyazma BV. [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. 2002. Modern applied statistics with S. 4th ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Villani F, Urbanelli S, Gad A, Nudelman S, Bullini L. 1986. Electrophoretic variation of Culex pipiens from Egypt and Israel. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 29:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova EB. 2000. Culex pipiens pipiens mosquitoes: taxonomy, distribution, ecology, physiology, genetics, applied importance and control. Sofia (Bulgaria); Moscow (Russia): Pensoft. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DA, Kyriacou CP, Greenacre ML, Yu Q, Rutila JE, Rosbash M, Hall JC. 1991. Molecular transfer of a species-specific behavior from Drosophila simulans to Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 251:1082–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Metterville D, Briscoe AD, Reppert SM. 2007. Insect cryptochromes: gene duplication and loss define diverse ways to construct insect circadian clocks. Mol Biol Evol. 24:948–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan S, Merlin C, Boore JL, Reppert SM. 2011. The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration. Cell. 147:1171–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Yuan Q, Briscoe AD, Froy O, Casselman A, Reppert SM. 2005. The two CRYs of the butterfly. Curr Biol. 15:R953–R954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.