Abstract

Focal limbic seizures often impair consciousness/awareness with major negative impact on quality of life. Recent work has shown that limbic seizures depress brainstem arousal systems, including reduced action potential firing in a key node: cholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT). In vivo whole-cell recordings have not previously been achieved in PPT, but are used here with the goal of elucidating the mechanisms of reduced PPT cholinergic neuronal activity. An established model of focal limbic seizures was used in rats following brief hippocampal stimulation under light anesthesia. Whole-cell in vivo recordings were obtained from PPT neurons using custom-fabricated 9-10mm tapered patch pipettes, and cholinergic neurons were identified histologically. Average membrane potential, input resistance, membrane potential fluctuations and variance were analyzed during seizures. A subset of PPT neurons exhibited reduced firing and hyperpolarization during seizures and stained positive for choline acetyltransferase. These PPT neurons showed a mean membrane potential hyperpolarization of −3.82mV (±0.81 SEM, P<0.05) during seizures, and also showed significantly increased input resistance, fewer excitatory post-synaptic potential (EPSP)-like events (P<0.05), and reduced membrane potential variance (P<0.01). The combination of increased input resistance, decreased EPSP-like events and decreased variance weigh against active ictal inhibition and support withdrawal of excitatory input as the dominant mechanism of decreased activity of cholinergic neurons in the PPT. Further identifying synaptic mechanisms of depressed arousal during seizures may lead to new treatments to improve ictal and postictal cognition.

Introduction

The mechanisms by which subcortical activating networks regulate states of arousal have long been a subject of debate and experimentation, with evidence pointing to the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) as a crucial node in this far-reaching system (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017; Mena-Segovia et al., 2008; Moruzzi and Magoun, 1949; Steriade et al., 1990). The association of lesions in the brainstem tegmentum with the most extreme disturbance of arousal, coma, illustrates the critical role of brainstem structures in the regulation and maintenance of arousal (Parvizi and Damasio, 2003). Early scientific probes into the location of brainstem arousal structures studied the effects of sequential brainstem transections on wakefulness, and isolated the mesopontine area as one crucial to maintaining an awake state (Moruzzi and Magoun, 1949), with subsequent work identifying an important component of this system as cholinergic neurons in the PPT (Mesulam et al., 1983). A dominant target of PPT axonal fibers are thalamic nuclei (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017) known to play a central role in transitions between states of conscious arousal and their electrophysiological correlates (McCormick and Bal, 1997; Steriade et al., 1993). Of particular interest is the intralaminar central lateral nucleus of the thalamus, which has been shown to have decreased firing during focal limbic seizures (Feng et al., 2017), and also to rescue both electrophysiologic and behavioral measures of conscious arousal during seizures when stimulated (Gummadavelli et al., 2015b; Kundishora et al., 2017). The strong thalamic projections of cholinergic neurons in the PPT and their increased activity preceding transitions from sleep to wake and rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep, suggest a causal relationship between cholinergic PPT tone and transition to higher states of arousal (Steriade et al., 1990). Stimulation of intralaminar thalamic nuclei that are downstream targets of the ascending reticular activating system has even been shown to reverse electrophysiological and behavioral measures of decreased arousal in animal seizure models (Gummadavelli et al., 2015b; Kundishora et al., 2017).

Temporal lobe seizures are commonly associated with loss of consciousness despite the temporal lobes not being regarded as part of the canonical consciousness system (Blumenfeld, 2012). It is not immediately clear why persons with focal temporal lobe seizures should lose consciousness (Escueta et al., 1977), while patient HM, for example, was able to maintain consciousness after bilateral medial temporal resections (Escueta et al., 1977; Scoville and Milner, 1957). Evidence is now growing in support of a network inhibition hypothesis to explain these seeming disparities, proposing that the loss of consciousness accompanying focal epilepsies is mediated through suppression of subcortical arousal circuits (Blumenfeld, 2012; Norden and Blumenfeld, 2002).

The present study approaches a neuronal system associated with impaired consciousness/arousal in epilepsy, as opposed to consciousness itself. Recent work has shown that cholinergic PPT neuronal activity is decreased in an established model of focal temporal lobe seizures with decreased cortical arousal and that optogenetic stimulation of these neurons can reverse electrophysiological correlates of decreased arousal and increase gamma frequency cortical activity (Furman et al., 2015; Motelow et al., 2015). The afferent signaling regulating PPT activity and the mechanisms by which PPT neurons are modulated have yet to be clearly elucidated (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017). On a brain-wide scale, prior work has dissected out areas of inhibitory and excitatory activity during focal limbic seizures (Blumenfeld et al., 2004; Englot et al., 2008; Englot et al., 2009; Englot et al., 2010). At the cellular level, single-unit recordings have revealed that neurons of specific nuclei exhibit reduced neuronal firing during seizures (Motelow et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2016). In the present study, we delve into the intracellular membrane potential (Vm) level using in vivo whole-cell recordings from areas deep in the pedunculopontine brainstem to elucidate the synaptic mechanisms underlying ictal changes in neuronal activity of the PPT.

A subset of PPT neurons, identified as cholinergic, exhibit reduced firing during focal limbic seizures, but the mechanism of reduced firing is unknown. The activity of these neurons is likely modified by contributions of both excitatory and inhibitory input (Higley and Contreras, 2006; Isaacson and Scanziani, 2011; Wehr and Zador, 2003), however, the afferent synaptic changes resulting in decreased firing can be conceptually dichotomized into either an increase in inhibitory input, or a withdrawal of excitatory input.

Tight-seal whole-cell intracellular recording is a powerful tool for investigating membrane properties and synaptic input on individual neurons (Neher and Sakmann, 1976; Sakmann, 2006). The targeting of deep brain structures in vivo, however, has been limited by technical complications of their access, with prior reports removing large sections of brain tissue (e.g. cerebellectomy) to patch brainstem neurons (Martins and Froemke, 2015; Sugiyama et al., 2012). The network of brain circuitry involved in seizures likely extends far beyond areas of canonical seizure activity (Blumenfeld, 2012; Englot et al., 2008; Motelow et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2016), thus techniques such as slice preparations or in vivo studies that involve removal of large swaths of brain are less likely to produce meaningful data regarding distant seizure networks.

In the present study, a minimally invasive technique was used to access deep brainstem nuclei of the rat midbrain tegmentum, with negligible disturbance of brain architecture. In brief, borosilicate patch pipettes were fabricated with a 9-10mm taper and passed through ~300μm diameter craniotomies to the PPT. Using this technique, we attained stable, in vivo whole-cell recordings from neurons in the PPT while triggering focal limbic seizures.

The contributions of excitatory versus inhibitory input as regulators of neuronal activity are integral to answering questions regarding mechanisms by which neurons process information (Holt and Koch, 1997; Isaacson and Scanziani, 2011; Mitchell and Silver, 2003; Wehr and Zador, 2003). We identified a subset of reduced-firing hyperpolarizing (RfHp) neurons in the PPT, putatively cholinergic by histology. In addition to the RfHP phenotype, these PPT neurons exhibit a rise of input resistance (Rin) during seizures as well as a reduction in ictal membrane potential variance (σ2) and reduced frequency of EPSP-like events. The technical challenges associated with blind-patch recording from individual neurons and attaining whole cell configurations using a pipette embedded in 7mm of living neural tissue resulted in a low sample-size of neurons in this study. As such, firm conclusions from these data may be premature. The pattern of characteristics described here, however, could be explained by a mechanism of reduced excitatory synaptic input on cholinergic neurons in the PPT during seizures.

Methods

For complete methods, see Supplemental Methods online.

Experimental Design

Animal Preparation and Surgery.

All procedures were conducted in compliance with approved institutional animal care and use protocols. A total of 54 female Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) age 6 – 10 weeks, weighing 180 - 275g were used in these experiments. Female rats were used because seizures have been shown less likely to secondarily generalize in female rats compared to males.(Janszky et al., 2004; Mejías-Aponte et al., 2002) All surgeries were performed as previously described (see also Supplemental Methods) (Englot et al., 2008; Motelow et al., 2015).

LFP and MUA Electrophysiology.

Local field potential (LFP) and multiunit activity (MUA) from lateral orbitofrontal cortex (Ctx LFP & Ctx MUA), as well as LFP from hippocampi (Hc) were acquired and amplified as previously described (Motelow et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2016). Continuous recordings were made using Spike2 v8.06 (CED) software.

Seizure Induction.

Seizures were induced during a lightly anesthetized state as described previously (see also Supplemental Methods) (Englot et al., 2008; Motelow et al., 2015). Bipolar stimulating-recording electrodes were placed in the Hc bilaterally. Hc was stimulated, using a 2s, 60Hz square biphasic wave (1ms per phase). Hc stimulus current amplitude was titrated to produce focal hippocampal seizure activity based on polyspike discharges without propagation to frontal cortex. Propogation of polyspike activity to the orbitofrontal electrode was considered secondary generalization and such seizures were excluded from analyses. Because the reduced-firing hyperpolarizing phenotype (Figure 1) was observed in comparatively short seizures as well as longer ones, no lower threshold on duration of seizures was stipulated for inclusion in analyses (range of duration for included seizures was 6 to 72 seconds).

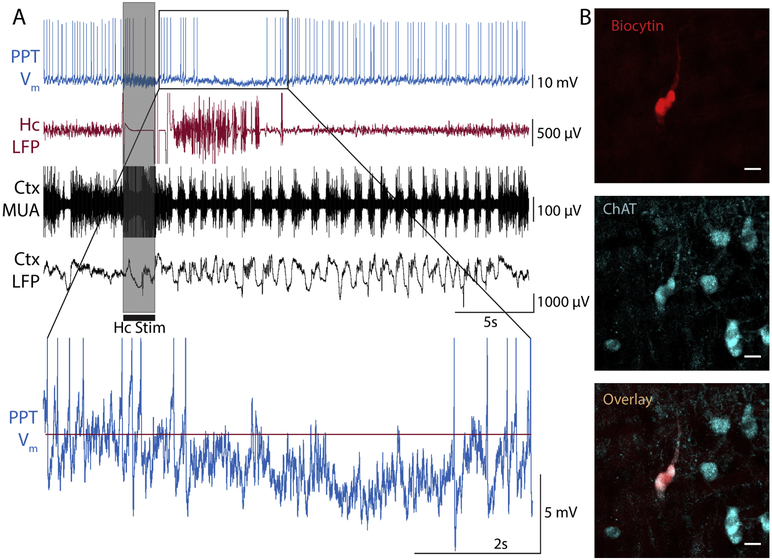

Figure 1. Reduced-firing hyperpolarizing (RfHp) neuron in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) during a focal limbic seizure.

(A) Whole-cell current clamp recording of membrane potential (Vm) in PPT neuron shows reduced firing and hyperpolarization (see inset) during a focal seizure induced in the hippocampus by a 2s, 60 Hz stimulus (gray bar). Concomitant recording of local field potential (LFP) shows polyspike seizure activity in the hippocampus (Hc). Orbital frontal cortex (Ctx) LFP exhibit slow-waves and multiunit activity (MUA) recordings show Up/Down state firing at seizure onset lasting into the postictal period. (B) Histology demonstrates co-localization of biocytin (from intracellular electrode solution) staining and ChAT immunohistochemistry for neuron recorded in A. Scale bar is 20 microns.

Whole-cell recordings.

For whole-cell recordings from PPT, procedures used previously for more superficial targets were modified (See also Supplemental Methods) (McGinley et al., 2015). The PPT was targeted at coordinates (relative to bregma) AP −7.8; ML ±1.8; Depth 7.0 mm. A potassium-gluconate-based intracellular solution with 0.5% Biocytin, the same as is used for in vitro whole cell recordings(Neske et al., 2015), was used for micropipettes. Borosilicate glass pipettes (1B150F-4, World Precision instruments) were fabricated using a multi-line program to have a long 9-10mm taper to allow recordings deep below the cortical surface, and a resistance of 3.5 – 6 MΩ, using a Sutter Instruments P-1000 micropipette puller.

Recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700B (Axon) amplifier and digitized at 25kHz using a Micro1401 (CED) and Spike2 v8.06 (CED) software. The neuron-searching step of acquiring whole cell recordings was undertaken in voltage-clamp mode, with current response visualized in real-time both in Spike2 software and on an external oscilloscope for blind-patching. The initial access resistance of most cells was between 20 - 40 MΩ.

Histology.

Brains were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and cut in 60μm slices for histology. Brains were then stained for biocytin cy3-streptavidin construct and co-stained using an antibody to Choline-acetyltransferase (ChAT; goat-α-choline acetyltransferase, Millipore, 1:500, #AB144P) as previously described(Motelow et al., 2015) (see also Supplemental Methods). To confirm locations of neurons, slices containing labelled neurons were compared to anatomical diagrams of rat brains (Paxinos and Watson, 1998) (supplemental figure S3).

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using Spike2 (CED, v5.20a), and in-house software written on MATLAB (R2009a, Mathworks). Analysis epoch were defined as follows: 1. Baseline: 20–0 s before stimulus; 2. Ictal: the first 20 s of hippocampal seizure activity (or the entire period of seizure activity where indicated), based on large amplitude, polyspike activity in the hippocampal LFP recordings; 3. Postictal: 0–20 s after seizure; 4. Recovery: 20 s following the postictal period. All included neurons had RC charging curve compatible with transition to intracellular recordings, exhibited reproducible action potentials, and stable resting potential (see Supplemental Methods for details). Statistical significance threshold for Student’s two-tailed t-test was p < 0.05, with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons where appropriate.

Neuronal spiking rate analysis.

Spike sorting on the whole cell recordings was performed in Spike 2 using template-matching based on waveform shapes to identify single units. Raster plots of neuronal firing were generated for each neuron, and then histograms of mean firing rate were calculated across neurons in 1s non-overlapping bins for each epoch (Figures 2 and supplemental figure S3).

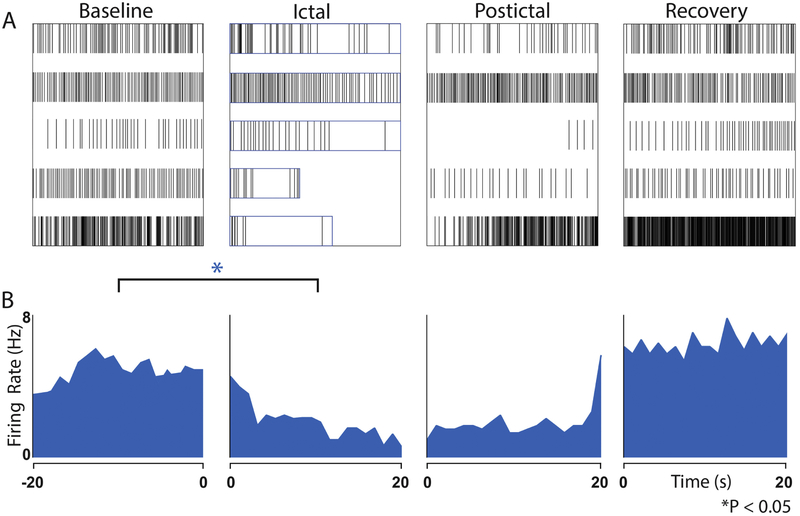

Figure 2. Reduced action potential firing in RfHp neurons during seizures.

(A) Raster plots (five cells from five animals) show decreased firing during the Ictal period compared with Baseline. Boxes in ictal panel indicate duration of seizures up to the first 20 s. (B) Histograms of firing rate in 1 s bins across neurons. Mean reduction in firing rate of Ictal compared to Baseline epochs was −51.6% (SEM 12.8%, * p < 0.05, paired t-test). Baseline is defined as the 20 s preceding seizure onset. Ictal is defined as up to the first 20 s following seizure onset. Postictal is the first 20 s following seizure end. Recovery is the 20 s following the Postictal period.

Vm hyperpolarization during seizures vs. baseline.

Membrane potential in baseline and ictal epochs were averaged in 3s bins after excluding the 20ms period surrounding each action potential (5ms prior, 15ms following). The bin just prior to seizure stimulation (within the baseline period) was compared to the bin of most negative membrane potential during the ictal period to determine the amplitude of ictal hyperpolarization. Time course graphs of mean change in membrane potential, Vm (mV) were constructed using 3s bins of Vm data (Figure 3 C). Absolute change from baseline Vm was calculated by taking the mean baseline Vm for the 20s prior to seizure onset, and subtracting that mean baseline Vm from all plotted 3s Vm bins. Baseline bins were compared to ictal bins using a two-tailed t-test, α = 0.05.

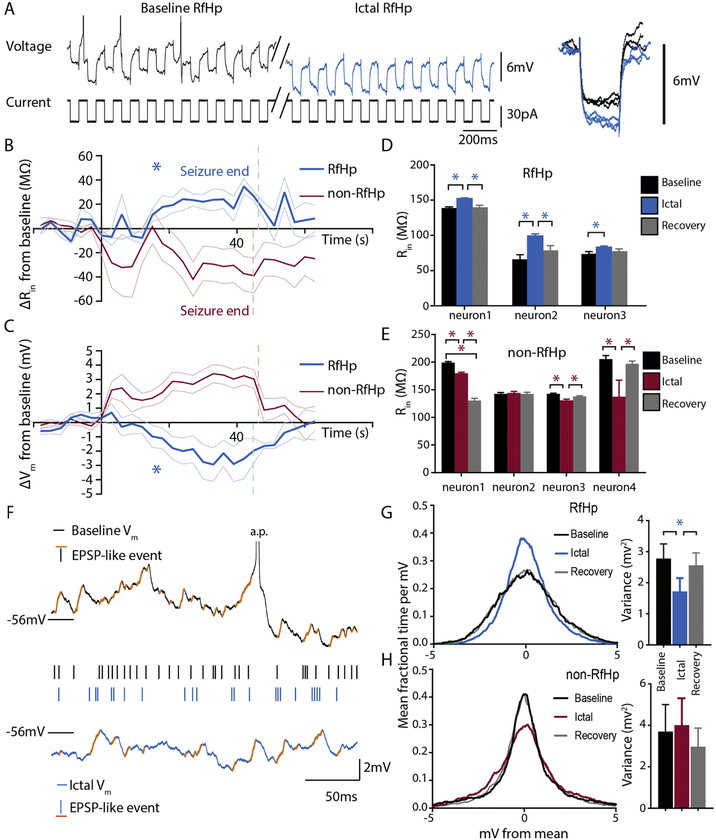

Figure 3. Increased input resistance and reduced membrane potential fluctuations in RfHp neurons during seizures.

(A) Example of response to continuous 10Hz 30pA square current pulses in an RfHp neuron (top trace, Voltage; bottom trace, Current). Action potentials are truncated. The trace shows reduced firing and hyperpolarization in the ictal period (blue), as well as a larger magnitude of Vm response to constant current steps, indicating an increase in ictal input resistance. Inset on right shows expanded view of baseline (black) and ictal (blue) Vm responses to current pulses, with resting potentials aligned vertically to enable differences in response amplitude to be compared more easily.

(B) Mean time course of absolute change in mean input resistance (Rin) during seizures reveal that the increase in mean Rin for RfHp neurons (blue) was significant during the ictal period (P<0.05, two-tailed t-test). Seizure onset was at time 0, and ends of seizure epochs are indicated by vertical dashed lines for RfHp (blue, n=3) and non-RfHp (red, n=4) neurons. Traces show mean change in Rin (Rin – baseline Rin) from baseline with standard error of mean (SEM).

(C) Mean time course of change in mean Vm from baseline (Vm – baseline Vm) for the same neurons in (B) and over the same time course, showing significant hyperpolarization during the ictal period (P<0.05, two-tailed t-test).

(D, E) Changes in input resistance (Rin) for individual RfHp and non-RfHp neurons. RfHp neurons (D) show consistent increases in Rin during the ictal period compared to baseline. (* P < 0.05, paired, two-tailed t-test, Holm-Bonferroni corrected). None of the non-RfHp neurons (E) show significant increase in Rin during seizures. For (D) and (E) mean and SEM are shown across each neuron that received current pulses, with SEMs obtained across current pulses for each period.

(F) Examples of EPSP-like events defined as positive fluctuations in membrane potential of >0.4mV with a rise-time of <2ms (Koch, 2004; Mason et al., 1991). Top (black) trace shows the baseline Vm of an RfHp neuron, while the lower (blue) trace shows ictal Vm of the same RfHp neuron. Orange markings overly EPSP-like events, with each event also marked as a black (baseline) or blue (ictal) tick-mark for easier comparison of relative frequency. In group analysis, frequency of EPSP-like events was significantly decreased during the ictal periods of RfHp neurons compared to baseline (see text).

(G,H) Average membrane potential histograms for RfHp neurons (n=4) (G) and non-RfHp neurons (n=10) (H) in the Baseline, Ictal and Recovery periods, presented side-by-side with bar graphs quantifying variance. Mean histogram for RfHp neurons was narrower for the ictal period (blue), and the corresponding membrane potential variance of RfHp neurons was significantly decreased during seizures compared to baseline (* P < 0.05, paired two-tailed t-test, Holm- Bonferroni corrected)

Input resistance (Rin).

Input resistance was measured by delivering repeated hyperpolarizing square current pulses and measuring the change in membrane potential for each step, as resistance (R) is related to change in voltage (ΔV) and current (ΔI) through Ohm’s law R=ΔV/ΔI. Square hyperpolarizing pulses were delivered at a constant frequency and amplitude during the recording of each neuron (Figure 3 A). Time course graphs of mean absolute ictal changes in Rin (MΩ) were constructed using 3s bins of Rin data (Figure 3 B). Absolute change from baseline Rin was calculated by taking the mean baseline Rin for the 20s prior to seizure onset, and subtracting that mean baseline Rin from all plotted 3s Rin bins. Baseline bins were compared to ictal bins using a two-tailed t-test, α = 0.05.

Analysis of EPSP-like events and voltage histograms.

EPSP-like events were identified in MATLAB as positive fluctuations in membrane potential of >0.4mV with a rise-time of <2ms (Koch, 2004; Mason et al., 1991), excluding the time periods from 5ms before to 15ms after any action potentials (Figure 3 F). Constraints of the model did not allow for full validation of these as canonical EPSPs (see Discussion), so the descriptive term “EPSP-like events” is used instead.

As an additional measure of synaptic activity, we investigated the variance of voltage before, during and after seizures. Variance in these epochs was compared using paired two-tailed t-tests. To graphically depict membrane potential distribution, we created voltage histograms centered to the mean of a fitted Gaussian. Histogram values were divided by the total number of samples in each histogram to obtain fractional time per mV for each bin, and averaged bin by bin across neurons with equal weight (Figure 3 G, H).

Results

Reduced-firing, hyperpolarizing neurons of the PPT

Our goal was to find the mechanism for reduced firing of cholinergic neurons in PPT. To this end, whole-cell configuration was attained from 36 neurons in the stereotactic area of the PPT, after a total of 295 pipette passes into the brains of 54 rats. 5 neurons showed a distinct electrophysiological phenotype of reduced firing and hyperpolarization (RfHp), as seen in Figure 1 A, and are the focus of this study. Electrophysiologic definition of RfHp as used in this paper is as follows: 1. a reduction in ictal rate of firing, and 2. a mean membrane potential hyperpolarized >1.0 mV relative to baseline during the last half of ictus; both compared to the 20s preceding seizure stimulation. Following hippocampal stimulation, seizure activity is seen localized to the hippocampus and there is a sharp transition in cortical LFP from fast activity with sparse slow waves to synchronized cortical slow waves and MUA Up/Down firing states (Figure 1 A) similar to slow wave sleep (Englot et al., 2008; Motelow et al., 2015). During the seizure, the PPT neuron’s firing tapers off and is silenced for the majority of the ictal period, while the membrane potential shows hyperpolarization (Figure 1 A, inset). Co-staining with biocytin (from the whole-cell pipette) and ChAT was used to identify recovered RfHp neurons as cholinergic (Figure 1 B).

Most neurons that were recorded did not show the RfHp phenotype and are therefore referred to in this study as non-RfHp neurons (supplemental figure S1). The locations of all histologically recovered neurons are shown in supplemental figure S2. Among the 5 neurons observed to show the RfHp phenotype on electrophysiology and included in firing rate analysis (Figure 2), 4 were recovered histologically. All (4 of 4) recovered RfHp neurons expressed ChAT positivity (supplemental figure S2), whereas none of the recovered non-RfHp neurons (0 of 12) were ChAT positive (P<0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

The action potential firing of RfHp neurons before, during and after focal seizures is depicted in the raster plots in Figure 2 A. Histograms in Figure 2 B present the average firing rate in 1s bins over the course of each 20s epoch. Baseline rate of firing varied among neurons, but there was a consistent reduction in firing rate of RfHP neurons during the ictal period relative to baseline (mean decrease −51.6%, SEM 12.8%, P<0.05). For the purposes of directly comparing seizures of differing lengths, only up to the first 20s of the ictal epoch are depicted in Figure 2 and used in statistical analysis. In neurons whose seizures lasted longer than 20s (raster plots at the top of Figure 2 A) firing continues to decrease during the later portions of the seizure outside the epoch depicted in the plots. All non-RfHp, ChAT-negative neurons showed either increases or no change rate of firing during seizures, with one exception that showed a small decrease in firing (supplemental figure S3). No neurons in the non-RfHp group showed mean ictal hyperpolarization >1.0 mV during the latter half of seizures, nor did any show mean ictal hyperpolarization >0.5mV during the entire seizure. Similarly, previous extracellular recordings (without membrane potential measurements) of ChAT-negative neurons in the area of the PPT showed either increases, no change or less commonly decreases in firing rate (Motelow et al., 2015). Because the PPT contains neurons of at least 3 different neurotransmitter subtypes (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017), ChAT-negative neurons likely represent subpopulations of GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017; Motelow et al., 2015).

All RfHp neurons exhibited an ictal hyperpolarization relative to baseline pre-ictal membrane voltages. The mean membrane potential of RfHp neurons during the 20s baseline prior to seizure onset ranged from −53.73mV to −64.67mV (SEM±2.13), adjusted for junction potential. The average amplitude of ictal hyperpolarization for RfHp neurons was −3.82mV (n=4, SEM±0.81, P<0.05) relative to the pre-ictal baseline membrane potential. In contrast, for non-RfHp neurons, the most hyperpolarized ictal Vm during seizures was on average no different than baseline: +0.85mV (SEM±0.43, n=10, P=0.097).

Input resistance and voltage fluctuation during seizures

Dichotomizing the mechanistic options underlying a phenotype of reduced firing and hyperpolarization offers two simplified extremes: active inhibition versus a withdrawal of baseline excitatory input. Active inhibition is expected to decrease neuronal input impedance and to increase spontaneous membrane potential fluctuations, whereas withdrawal of excitation should have the opposite effects. Because the RfHp neurons were electrophysiologically identified by properties measurable in current-clamp mode, experiments were continued in current-clamp with the addition of low-amplitude, continuous, square current-steps to measure moment-to-moment input resistance. 3 RfHp neurons and 4 non-RfHp neurons were recorded with these repeated brief current pulses to quantify input resistance before, during and after seizures. Figure 3 A shows an RfHp ChAT-positive neuron while 30pA 50ms current pulses are delivered at a rate of 10Hz. Spikes seen in the baseline (black) trace of Figure 3 A are truncated to allow an expanded view of the Vm response to current steps (and action potentials were excluded from analysis; see Methods). The ictal trace (blue) shows reduced firing and hyperpolarization characteristic of the RfHp neurons. The ictal period of RfHp neurons is accompanied by an increase in magnitude of voltage response to constant current pulses, indicating an increase in input resistance.

The mean time-course of input resistance change during seizures is shown for RfHp vs non-RfHp neurons in Figure 3 B, and corresponding changes in Vm are depicted in Figure 3 C. The increases in mean Rin for RfHp neurons (blue) from baseline to ictal periods (15.6 ± SEM 4.3 MΩ) were statistically significant (P<0.05, two-tailed t-test). These increases in Rin were on the same time-scale as the Vm hyperpolarization of RfHp neurons (blue). This is depicted in the time-course graph of Vm (figure 3 C) for the same neurons during the same time periods, showing a significant hyperpolarization relative to baseline during ictus (−1.5 ± SEM 0.3 mV; P<0.05, two-tailed t-test).

Mean ictal input resistance changes for individual RfHp and non-RfHp neurons are shown in Figure 3 D, E. 3 of 3 RfHp neurons showed a significant (P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P<0.05; neuron 1, 2 & 3 respectively, baseline vs ictal Rin; paired, two-tailed t-test) increase in mean input resistance during the ictal phase, whereas 0 of 4 non-RfHp neurons exhibited significant ictal increases in input resistance (P<0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Input resistance measurements were repeated in 2 of the RfHp neurons in non-ictal periods (one prior to seizure onset, one following seizure end) in which the membrane potential was hyperpolarized by current injection to reach the same voltage measured during the ictal period. This was done to determine if membrane potential hyperpolarization alone was responsible for the changes in input resistance. In both instances of hyperpolarization alone (without seizures), ictal input resistance was still significantly higher than these non-ictal periods with comparable hyperpolarization (data not shown: neuron 2 post-seizure hyperpolarized 87.5 MΩ ± SEM 2.1, vs ictal 99.0 MΩ ± SEM 3.1, P < 0.01; neuron 3 pre-ictal hyperpolarized 72.4 MΩ ± SEM 1.8, vs ictal 83.2 MΩ ± SEM 1.7, P < 0.01). This suggests that the change in input resistance observed ictally is not fully explained by closure of voltage-gated ion channels with hyperpolarization.

Identifying EPSPs in the absence of voltage-gated channel blockers and without a known timed afferent stimulus—i.e., on morphology alone—is insufficient for unequivocal categorization as an excitatory post-synaptic potential. For the purposes of this study, morphological characteristics of positive deflection amplitude and rise-times were chosen based on descriptions of well-characterized EPSP’s in the literature (Koch, 2004; Mason et al., 1991). The events meeting these less stringent criteria are referred to in this study as EPSP-like-events. We examined the membrane potential for discrete EPSP-like events by detecting positive deflections of >0.4mV in a time-frame of <2ms (Koch, 2004; Mason et al., 1991) (Figure 3 F). The frequency of EPSP-like events was significantly decreased during the ictal periods of RfHp neurons compared to baseline (mean baseline frequency: 97.6 Hz, ± SEM 20.7; mean ictal frequency: 88.7 Hz, ± SEM 19.0; n=4; P<0.05 paired, two-tailed t-test). Mean amplitude of EPSP-like events in RfHp neurons was not significantly different between baseline and ictal periods (mean Baseline amplitude: 0.59mV, SEM±0.07; mean Ictal amplitude 0.55mV, SEM±0.04; n=4; P = 0.113 paired, two-tailed t-test). Non-RfHp neurons showed no consistent or significant differences between frequency or amplitude of EPSP-like events in the ictal period compared to baseline (data not shown).

The distribution of membrane potential fluctuations was also plotted comparing baseline to ictal periods (Figure 3 G, H). The mean membrane potential variance of RfHp neurons decreased during seizures (mean σ2=1.72 mV2, SEM±0.43) compared to baseline (mean σ2=2.78 mV2, SEM±0.47, n=4; P<0.01 paired, two-tailed t-test). In contrast, the membrane potential variance in non-RfHp neurons trended toward increasing during seizures (mean σ2=4.01 mV2, SEM±1.27) compared to baseline (mean σ2=3.70 mV2, SEM±1.37) but was not statistically significant (n=10; P = 0.582). These changes in membrane potential fluctuations and EPSP-like events, along with increased input resistance suggest that synaptic input may be reduced to RfHp neurons during seizures.

Discussion

Evidence continues to build suggesting that impaired consciousness accompanying focal seizures is not simply a function of acute over-activation of cortical neurons, but rather involves far-reaching effects of seizures on subcortical arousal systems (Blumenfeld, 2012; Blumenfeld et al., 2004; Englot and Blumenfeld, 2009; Englot et al., 2008; Englot et al., 2009; Englot et al., 2010; Furman et al., 2015; Kundishora et al., 2017; Motelow et al., 2015). In this study, we overcame the technical challenges of deep brain surface-to-target whole cell recordings to attain the first in vivo whole cell recordings of neurons in the PPT. These recordings reveal membrane property changes in this key arousal nucleus during focal seizures and provide mechanistic insight into cholinergic neurons with reduced firing during seizures (Motelow et al., 2015). Membrane potential hyperpolarization was accompanied by increased input resistance, decreased spontaneous membrane potential fluctuations and reduced EPSP-like events during seizures. These results suggest that reduced firing in putative cholinergic (RfHp) PPT neurons arises mainly from decreased excitatory synaptic input during seizures. The focus of this study was a subset of neurons within a single brainstem nucleus, therefore its generalizability to higher level questions of consciousness systems should be tempered. However, while the present study taken in isolation is limited in scope with regards to mechanisms of consciousness, it builds on prior work showing a consistent link between states of conscious arousal and acetylcholine, the PPT and possible thalamic targets of the PPT (Feng et al., 2017; Furman et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Motelow et al., 2015).

Postsynaptic hyperpolarization of a neuron could be caused by active inhibition, such as through GABAergic input opening chloride channels. If the dominant input causing this hyperpolarization was increased GABAergic input, one would anticipate a decrease in Rin to accompany the opening of channels (Steriade, 2004). The consistent increase in Rin observed accompanying the hyperpolarization of RfHp neurons during seizures argues against direct GABAergic input on these neurons as the dominant mechanism of reduced activity. However, the contribution of changes in inhibitory tone on these neurons has not been entirely ruled out with the present experiments, and should be investigated further under depolarized conditions or in voltage clamp to definitively study inhibitory currents.

Another possible mechanism for hyperpolarization is a sudden decrease in baseline excitatory synaptic input. Neurons in vivo are bombarded by synaptic activity that is integrated into that neuron’s rate of firing (Chance et al., 2002; Destexhe and Paré, 1999). Because one explanation for the increase in Rin observed during seizures is a reduction in excitatory synaptic input, it follows that measures of synaptic input on RfHp neurons might show a decrease during seizures. When studying postsynaptic potentials (PSPs), excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) or mini-EPSPs (mEPSPs), distinguishing these events in current-clamp recordings can be made clearer by the uses of voltage-gated channel blockers to reduce the contamination of data by action potentials, as well as having a known stimulus—e.g. an external input or an action potential from a nearby neuron—after which to focus data analysis (Deweese and Zador, 2004; Mason et al., 1991). While we did not have these advantages, EPSP and mEPSP morphology has been described in detail and is the centerpiece of many PSP analyses of current-clamp data (DeWeese and Zador, 2006; Koch, 2004; Mason et al., 1991). A positive deflection of ≥0.4mV in ≤2ms was chosen as criteria for EPSP-like events based on rise-times and amplitudes of EPSPs reported in the literature (Koch, 2004; Magee and Cook, 2000; Mason et al., 1991). Advantages of such morphological analyses of discrete positive Vm fluctuations include protection from biases from slower non-synaptic changes in membrane potential, which could be difficult to eliminate from broader analyses of membrane potential variance. The finding of decreased EPSP-like events during the ictal period of RfHp neurons provides additional evidence in favor of reduced excitatory input underlying the increased Rin and concomitant reduction in both membrane potential and neuronal firing observed in RfHp neurons during seizures. It should be noted that the contributions of reduced excitatory input detailed here do not in-and-of-themselves rule out contributions from inhibitory tone or neuromodulation. Multiple mechanisms may indeed contribute to the electrophysiologic changes observed, and more work is necessary for their proper elucidation. Such experiments should include voltage clamp to characterize currents and experiments at depolarized membrane potentials to study inhibitory drive.

Neurons of the PPT are the major source of cholinergic input to the thalamus (Mesulam et al., 1989; Mesulam et al., 1983) and have been shown to play a role in cortical transitions between slow-wave, low-arousal states to a higher arousal state (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017; Steriade et al., 1990), as well as the opposite direction, from cortical fast-to-slow activity associated with acute depression in arousal in a seizure model (Motelow et al., 2015). Prior work demonstrates the importance of depressed PPT and forebrain cholinergic neuronal activity during seizures, and shows decreased firing of these cholinergic neurons with a larger sample size than the present investigation (Furman et al., 2015; Motelow et al., 2015). This study provides a synaptic mechanism to explain such reduced firing in cholinergic neurons in the PPT during limbic seizures.

The PPT receives afferents from many areas, including the thalamus, basal ganglia, limbic system and cortex (Benarroch, 2013; Mesulam et al., 1989; Pahapill and Lozano, 2000). Theorizing as to which of these specifically underlie the ictal withdrawal of excitatory tone would be premature. However, these findings fit with prior work suggesting that network inhibition during focal limbic seizures arises from a polysynaptic mechanism, based on the latencies observed between activation of inhibitory lateral septal regions and initiation of slow waves in the cortex (Englot et al., 2009).

The technically challenging experimental approach of the present study provides a novel look into neurons of deep brainstem structures during limbic seizures, but also has limitations that should be addressed with future work. Specifically, the technical challenges of in vivo whole cell recordings deep below the brain’s surface resulted in relatively low sample sizes for some of the measurements, and necessitated use of anesthetic agents to achieve stable recordings. Because seizures must be spaced out in time to avoid inducing a refractory state in the hippocampus, neurons often were lost or had increased access resistance while waiting for the hippocampus to recover to trigger a second seizure. With only a single seizure available to analyze the phenotype of a neuron, compounded by a search for comparatively sparse cholinergic neurons in a heterogenous nucleus (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017) using a low-yield, time-intensive technique, emphasis was placed on current-clamp recordings for the ability to characterize the neuronal membrane properties. Estimates of the fraction of neurons expressing choline-acetyltransferase in the PPT range from 20 – 27% (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017; Wang and Morales, 2009). While our data was not collected in a manner sufficient for estimating the actual frequency of cholinergic neurons in PPT, the high ratio of non-ChAT to ChAT neurons recorded here is consistent with prior studies documenting ChAT neurons being in the minority in the PPT. A limitation of measuring changes in input resistance is a lack of specificity. However, Rin does become useful in the presence of other physiological data to provide clues as to the source and effect of these changes in resistance—namely changes in membrane potential and firing profiles. Moreover, direct measurements of input resistance can also give clues as to possible contributions of shunting inhibition (Holt and Koch, 1997; Mitchell and Silver, 2003), which, as evidenced by the increase in Rin, does not appear to be the mechanism of inhibition in this case. The relatively low sample size of RfHp neurons recorded is a function of the time-intensive, low-yield experiments that follow from combining an acute in vivo model of limbic seizures with performing whole cell recordings deep below the brain’s surface. More neurons are presumably always better, but in the presence of strong prior work with which to correlate functional neuronal characteristics and clear trends in firing activity and Rin, the authors believe that the present results are nevertheless of value to the field.

Another potential concern is the use of “light” ketamine/xylazine anesthesia which was necessary to obtain mechanical stability for the recordings (see Supplemental Methods). This affects the interpretation of this work both on the level of neuronal physiology as well as generalizability to consciousness/arousal. Regarding the latter, the rats in the experiment are under an artificially suppressed state of arousal from the ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. Thus, the added insult of a seizure is really an impairment of an already dampened system of arousal. Such a state leaves open opportunities for confounding effects of altering systems that have already been perturbed. On the subject of neuronal physiology, different anesthetics have been shown to achieve different patterns of cortical activity on EEG (Mahon et al., 2001). Ketamine, used in this study, is known to alter cellular physiology (Lydic and Baghdoyan, 2002; Mahon et al., 2001; Saponjic et al., 2006). We attempted to mitigate these effects by using as low a dose of anesthetic as possible, and by comparing results under identical anesthetic conditions before and during seizures, nevertheless ideally the present experiments should be repeated in awake animals. Because the actual feasibility of whole cell recordings in deep brainstem neurons without removal of surrounding architecture had not been demonstrated prior to this study, one may hope that the example of the present study will allow reasonable criticisms of the current model to be addressed in work to come. These studies also lay the groundwork for additional important future investigations, utilizing a combination of techniques including selective genetic modulation and imaging of individual neurons and pathways to more fully elucidate the network mechanisms of depressed subcortical arousal in focal seizures.

In summary, the present work demonstrates that putative cholinergic neurons of the PPT show a pattern of reduced firing and hyperpolarization, accompanied by increased input resistance, reduced Vm variance and reduced EPSP-like activity during seizures. As mentioned previously, the electrophysiologic patterns described in this paper are based on a relatively low number of neurons and more work is needed to draw firm conclusions about neuronal mechanisms influencing activity of PPT neurons. By demonstrating the possibility of such deep whole cell recordings, it is our hope that subcortical neuronal physiology will continue to be uncovered by expanding on these techniques. The initial properties of RfHp neurons in the present work support a mechanism of decreased excitatory input as the basis for decreased subcortical arousal originating in PPT. These results provide an example where ictal alterations of neurophysiology may occur through reductions in synaptic activity. This is an early step toward understanding the afferent drive of the PPT and its contribution to PPT activity (Mena-Segovia and Bolam, 2017). As clinical advances in treatment of neurophysiologic disorders to rely more on neuromodulation (Gummadavelli et al., 2015a; Gummadavelli et al., 2015b; Kundishora et al., 2017; Theodore and Fisher, 2004), studies of the basic neuronal mechanisms of functional pathology become less esotericisms and closer to clinical targets for disease-modifying therapies.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Non-RfHP neuron in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) during a focal limbic seizure. (A) Whole-cell current clamp recording of membrane potential (Vm) in PPT neuron shows continued tonic firing and no significant hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential during a focal seizure induced in the hippocampus by a 2s, 60 Hz stimulus (gray bar). Concomitant recording of local field potential (LFP) shows polyspike seizure activity in the hippocampus (Hc). Orbital frontal cortex (Cx) LFP and multiunit activity (MUA) show slow-wave and Up/Down state activity during and following the seizure. (B) Histology demonstrates biocytin staining (from intracellular electrode solution) but no ChAT staining by immunohistochemistry staining of the recorded neuron from A. Scale bar is 20 microns.

Figure S2. Anatomical locations of histologically recovered neurons. 16 neurons were recovered based on biocytin staining following whole-cell recordings. Red dots indicate the 4 reduced firing hyperpolarizing (RfHp) neurons that were recovered, all of which were verified to be choline acetyl transferase (ChAT)-positive. One RfHp neuron was not histologically recovered. Blue dots indicate the 12 histologically recovered non-RfHp neurons, all of which were ChAT-negative. AP coordinate of coronal sections are in millimeters relative to bregma. Schematics taken with permission from Paxinos and Watson, 1998.

Figure S3. Non-RfHp neurons showed variable pattern of firing during seizures. (A) Raster plots of 12 cells from 10 animals show variable pattern firing during the Ictal period with an overall increase compared with Baseline. Boxes in ictal panel indicate duration of seizures up to the first 20 s. (B) Histograms of firing rate in 1 s bins across neurons. Mean change in firing rate trended upward during Ictal periods compared to Baseline, with high levels variation among non-RfHp neurons resulting in no statistically significant mean change (+465.9%, SEM 192.2%, P = 0.096, t-test). 1 non-RfHp neuron showed no action potentials during the Baseline, Ictal, Postictal and Recovery periods, represented by the blank base at the bottom of part (A). Baseline is 20 s prior to seizure onset. Ictal is the first 20 s following seizure onset. Postictal is the first 20 s following seizure end. Recovery is the 20 s following the Postictal period.

Highlights.

Whole-cell in vivo recordings were made from PPT neurons in a rat model of limbic seizures.

Cholinergic neurons in the PPT show reduced firing and hyperpolarization during seizures.

Changes in input resistance, membrane potential variance and EPSP-like events suggest reduced excitatory input.

Acknowledgements

We thank Quentin Perrenoud and Jessica Cardin for helpful suggestions on whole-cell in vivo recordings. This work was supported by NIH R01 NS066974, R01 NS096088 (H.B.) and by an HHMI-CURE fellowship (J.A.).

Footnotes

Disclosure

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benarroch EE, 2013. Pedunculopontine nucleus: functional organization and clinical implications. Neurology 80, 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, 2012. Impaired consciousness in epilepsy. The Lancet Neurology 11, 814–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, McNally KA, Vanderhill SD, Paige AL, Chung R, Davis K, Norden AD, Stokking R, Studholme C, Novotny EJ, Zubal IG, Spencer SS, 2004. Positive and negative network correlations in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cerebral Cortex 14, 892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance FS, Abbott L, Reyes AD, 2002. Gain modulation from background synaptic input. Neuron 35, 773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, Paré D, 1999. Impact of network activity on the integrative properties of neocortical pyramidal neurons in vivo. Journal of neurophysiology 81, 1531–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deweese MR, Zador AM, 2004. Shared and private variability in the auditory cortex. Journal of neurophysiology 92, 1840–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese MR, Zador AM, 2006. Non-Gaussian Membrane Potential Dynamics Imply Sparse, Synchronous Activity in Auditory Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 26, 12206–12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Blumenfeld H, 2009. Consciousness and epilepsy: why are complex-partial seizures complex? Progress in brain research 177, 147–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Mishra AM, Mansuripur PK, Herman P, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H, 2008. Remote effects of focal hippocampal seizures on the rat neocortex. J Neurosci 28, 9066–9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Modi B, Mishra AM, DeSalvo M, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H, 2009. Cortical deactivation induced by subcortical network dysfunction in limbic seizures. J Neurosci 29, 13006–13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Yang L, Hamid H, Danielson N, Bai X, Marfeo A, Yu L, Gordon A, Purcaro MJ, Motelow JE, Agarwal R, Ellens DJ, Golomb JD, Shamy MC, Zhang H, Carlson C, Doyle W, Devinsky O, Vives K, Spencer DD, Spencer SS, Schevon C, Zaveri HP, Blumenfeld H, 2010. Impaired consciousness in temporal lobe seizures: role of cortical slow activity. Brain 133, 3764–3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escueta AV, Kunze U, Waddell G, Boxley J, Nadel A, 1977. Lapse of consciousness and automatisms in temporal lobe epilepsy A videotape analysis. Neurology 27, 144–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Motelow JE, Ma C, Biche W, McCafferty C, Smith N, Liu M, Zhan Q, Jia R, Xiao B, 2017. Seizures and sleep in the thalamus: Focal limbic seizures show divergent activity patterns in different thalamic nuclei. Journal of Neuroscience, 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman M, Zhan Q, McCafferty C, Lerner BA, Motelow JE, Meng J, Ma C, Buchanan GF, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Cardin JA, Blumenfeld H, 2015. Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic brainstem neurons during focal limbic seizures: Effects on cortical physiology. Epilepsia 56, e198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummadavelli A, Kundishora AJ, Willie JT, Andrews JP, Gerrard JL, Spencer DD, Blumenfeld H, 2015a. Improving level of consciousness in epilepsy with neurostimulation. Neurosurgical Focus 38(6), E10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummadavelli A, Motelow JE, Smith N, Zhan Q, Schiff ND, Blumenfeld H, 2015b. Thalamic stimulation to improve level of consciousness after seizures: evaluation of electrophysiology and behavior. Epilepsia 56, 114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley MJ, Contreras D, 2006. Balanced excitation and inhibition determine spike timing during frequency adaptation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 26, 448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt GR, Koch C, 1997. Shunting inhibition does not have a divisive effect on firing rates. Neural computation 9, 1001–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson Jeffry S., Scanziani M, 2011. How Inhibition Shapes Cortical Activity. Neuron 72, 231–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janszky J, Schulz R, Janszky I, Ebner A, 2004. Medial temporal lobe epilepsy: gender differences. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 75, 773–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C, 2004. Biophysics of computation: information processing in single neurons. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Kundishora AJ, Gummadavelli A, Ma C, Liu M, McCafferty C, Schiff ND, Willie JT, Gross RE, Gerrard J, Blumenfeld H, 2017. Restoring Conscious Arousal During Focal Limbic Seizures with Deep Brain Stimulation. Cereb Cortex 27, 1964–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Motelow JE, Zhan Q, Hu Y-C, Kim R, Chen WC, Blumenfeld H, 2015. Cortical network switching: possible role of the lateral septum and cholinergic arousal. Brain stimulation 8, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA, 2002. Ketamine and MK-801 Decrease Acetylcholine Release in the Pontine Reticular Formation, Slow Breathing, and Disrupt Sleep. Sleep 25, 615–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Cook EP, 2000. Somatic EPSP amplitude is independent of synapse location in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature neuroscience 3, 895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon S, Deniau J-M, Charpier S, 2001. Relationship between EEG potentials and intracellular activity of striatal and cortico-striatal neurons: an in vivo study under different anesthetics. Cerebral Cortex 11, 360–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins ARO, Froemke RC, 2015. Coordinated forms of noradrenergic plasticity in the locus coeruleus and primary auditory cortex. Nature Neuroscience 18, 1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason A, Nicoll A, Stratford K, 1991. Synaptic transmission between individual pyramidal neurons of the rat visual cortex in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience 11, 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Bal T, 1997. Sleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanisms. Annual review of neuroscience 20, 185–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley Matthew J., David Stephen V., McCormick David A., 2015. Cortical Membrane Potential Signature of Optimal States for Sensory Signal Detection. Neuron 87, 179–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejías-Aponte CA, Jiménez-Rivera CA, Segarra AC, 2002. Sex differences in models of temporal lobe epilepsy: role of testosterone. Brain research 944, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena-Segovia J, Bolam JP, 2017. Rethinking the Pedunculopontine Nucleus: From Cellular Organization to Function. Neuron 94, 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena-Segovia J, Sims HM, Magill PJ, Bolam JP, 2008. Cholinergic brainstem neurons modulate cortical gamma activity during slow oscillations. The Journal of physiology 586, 2947–2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M, Geula C, Bothwell MA, Hersh LB, 1989. Human reticular formation: cholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei and some cytochemical comparisons to forebrain cholinergic neurons. Journal of Comparative Neurology 283, 611–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M, Mufson E, Wainer B, Levey A, 1983. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1–Ch6). Neuroscience 10, 1185–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Silver RA, 2003. Shunting Inhibition Modulates Neuronal Gain during Synaptic Excitation. Neuron 38, 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moruzzi G, Magoun HW, 1949. Brain stem reticular formation and activation of the EEG. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology 1, 455–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motelow Joshua E., Li W, Zhan Q, Mishra Asht M., Sachdev Robert N.S., Liu G, Gummadavelli A, Zayyad Z, Lee Hyun S., Chu V, Andrews John P., Englot Dario J., Herman P, Sanganahalli Basavaraju G., Hyder F, Blumenfeld H, 2015. Decreased Subcortical Cholinergic Arousal in Focal Seizures. Neuron 85, 561–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakmann B, 1976. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neske GT, Patrick SL, Connors BW, 2015. Contributions of Diverse Excitatory and Inhibitory Neurons to Recurrent Network Activity in Cerebral Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 35, 1089–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden AD, Blumenfeld H, 2002. The role of subcortical structures in human epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior 3, 219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahapill PA, Lozano AM, 2000. The pedunculopontine nucleus and Parkinson's disease. Brain 123, 1767–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Damasio AR, 2003. Neuroanatomical correlates of brainstem coma. Brain 126, 1524–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, 1998. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, 4 ed. Academic Press, San Diego, London. [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, 2006. Patch pipettes are more useful than initially thought: simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recording from mammalian CNS synapses in vitro and in vivo. Pflügers Archiv 453, 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saponjic J, Radulovacki M, Carley DW, 2006. Modulation of respiratory pattern and upper airway muscle activity by the pedunculopontine tegmentum: role of NMDA receptors. Sleep and Breathing 10, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoville WB, Milner B, 1957. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 20, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, 2004. Acetylcholine systems and rhythmic activities during the waking–sleep cycle. Progress in brain research 145, 179–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Datta S, Pare D, Oakson G, Dossi RC, 1990. Neuronal activities in brain-stem cholinergic nuclei related to tonic activation processes in thalamocortical systems. Journal of Neuroscience 10, 2541–2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ, 1993. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 262, 679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama D, Hur SW, Pickering AE, Kase D, Kim SJ, Kawamata M, Imoto K, Furue H, 2012. In vivo patch-clamp recording from locus coeruleus neurones in the rat brainstem. The Journal of physiology 590, 2225–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore WH, Fisher RS, 2004. Brain stimulation for epilepsy. The Lancet Neurology 3, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Morales M, 2009. Pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei contain distinct populations of cholinergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons in the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience 29, 340–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr M, Zador AM, 2003. Balanced inhibition underlies tuning and sharpens spike timing in auditory cortex. Nature 426, 442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Buchanan GF, Motelow JE, Andrews J, Vitkovskiy P, Chen WC, Serout F, Gummadavelli A, Kundishora A, Furman M, Li W, Bo X, Richerson GB, Blumenfeld H, 2016. Impaired Serotonergic Brainstem Function during and after Seizures. The Journal of Neuroscience 36, 2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Non-RfHP neuron in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) during a focal limbic seizure. (A) Whole-cell current clamp recording of membrane potential (Vm) in PPT neuron shows continued tonic firing and no significant hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential during a focal seizure induced in the hippocampus by a 2s, 60 Hz stimulus (gray bar). Concomitant recording of local field potential (LFP) shows polyspike seizure activity in the hippocampus (Hc). Orbital frontal cortex (Cx) LFP and multiunit activity (MUA) show slow-wave and Up/Down state activity during and following the seizure. (B) Histology demonstrates biocytin staining (from intracellular electrode solution) but no ChAT staining by immunohistochemistry staining of the recorded neuron from A. Scale bar is 20 microns.

Figure S2. Anatomical locations of histologically recovered neurons. 16 neurons were recovered based on biocytin staining following whole-cell recordings. Red dots indicate the 4 reduced firing hyperpolarizing (RfHp) neurons that were recovered, all of which were verified to be choline acetyl transferase (ChAT)-positive. One RfHp neuron was not histologically recovered. Blue dots indicate the 12 histologically recovered non-RfHp neurons, all of which were ChAT-negative. AP coordinate of coronal sections are in millimeters relative to bregma. Schematics taken with permission from Paxinos and Watson, 1998.

Figure S3. Non-RfHp neurons showed variable pattern of firing during seizures. (A) Raster plots of 12 cells from 10 animals show variable pattern firing during the Ictal period with an overall increase compared with Baseline. Boxes in ictal panel indicate duration of seizures up to the first 20 s. (B) Histograms of firing rate in 1 s bins across neurons. Mean change in firing rate trended upward during Ictal periods compared to Baseline, with high levels variation among non-RfHp neurons resulting in no statistically significant mean change (+465.9%, SEM 192.2%, P = 0.096, t-test). 1 non-RfHp neuron showed no action potentials during the Baseline, Ictal, Postictal and Recovery periods, represented by the blank base at the bottom of part (A). Baseline is 20 s prior to seizure onset. Ictal is the first 20 s following seizure onset. Postictal is the first 20 s following seizure end. Recovery is the 20 s following the Postictal period.