Key Points

Question

Does prediagnostic 5α-reductase inhibitor use, with associated prostate-specific antigen suppression, lead to delayed diagnosis and increased risk of death from prostate cancer in a prostate specific antigen–screened population?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 80 875 men with prostate cancer, prediagnostic 5α-reductase inhibitor users had longer time from first elevated prostate-specific antigen test result to diagnosis, higher adjusted prostate-specific antigen at diagnosis, more advanced disease at diagnosis, and worse prostate cancer–specific and all-cause mortality compared with nonusers.

Meaning

Prediagnostic use of 5α-reductase inhibitors is associated with delayed prostate cancer diagnosis and increased mortality in men who underwent prostate-specific antigen screening.

This population-based cohort study examines medical records of 80 875 men who were treated at Veterans Affairs hospitals for prostate cancer to compare the time to diagnosis and mortality in men previously treated with 5α-reductase inhibitors for benign prostatic hyperplasia with those of men who received different or no treatment.

Abstract

Importance

5α-Reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), commonly used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia, reduce serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentrations by 50%. The association of 5-ARIs with detection of prostate cancer in a PSA-screened population remains unclear.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that prediagnostic 5-ARI use is associated with a delayed diagnosis, more advanced disease at diagnosis, and higher risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality and all-cause mortality than use of other or no PSA-decreasing drugs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study linked the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure with the National Death Index to obtain patient records for 80 875 men with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I-IV prostate cancer diagnosed from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2015. Patients were followed up until death or December 31, 2017. Data analysis was performed from March 2018 to May 2018.

Exposures

Prediagnostic 5-ARI use.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM). Secondary outcomes included time from first elevated PSA (defined as PSA≥4 ng/mL) to diagnostic prostate biopsy, cancer grade and stage at time of diagnosis, and all-cause mortality (ACM). Prostate-specific antigen levels for 5-ARI users were adjusted by doubling the value, consistent with previous clinical trials.

Results

Median (interquartile range [IQR]) age at diagnosis was 66 (61-72) years; median [IQR] follow-up was 5.90 (3.50-8.80) years. Median time from first adjusted elevated PSA to diagnosis was significantly greater for 5-ARI users than 5-ARI nonusers (3.60 [95% CI, 1.79-6.09] years vs 1.40 [95% CI, 0.38-3.27] years; P < .001) among patients with known prostate biopsy date. Median adjusted PSA at time of biopsy was significantly higher for 5-ARI users than 5-ARI non-users (13.5 ng/mL vs 6.4 ng/mL; P < .001). Patients treated with 5-ARI were more likely to have Gleason grade 8 or higher (25.2% vs 17.0%; P < .001), clinical stage T3 or higher (4.7% vs 2.9%; P < .001), node-positive (3.0% vs 1.7%; P < .001), and metastatic (6.7% vs 2.9%; P < .001) disease than 5-ARI nonusers. In a multivariable regression, patients who took 5-ARI had higher prostate cancer–specific (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52; P < .001) and all-cause (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05-1.15; P < .001) mortality.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this study demonstrate that prediagnostic use of 5-ARIs was associated with delayed diagnosis and worse cancer-specific outcomes in men with prostate cancer. These data highlight a continued need to raise awareness of 5-ARI-induced PSA suppression, establish clear guidelines for early prostate cancer detection, and motivate systems-based practices to facilitate optimal care for men who use 5-ARIs.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is a nonmalignant condition that affects more than 50% of men aged 50 years and older.1 One of the most common treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia is the class of medications called 5-α reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), which includes finasteride and dutasteride. By preventing the intraprostatic conversion of testosterone to the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone, these medications reduce prostate volume and relieve urinary outflow obstruction. 5-α Reductase inhibitors also depress serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentrations by approximately 50%.2

Randomized trials have shown that PSA screening remains effective for prostate cancer detection among men taking 5-ARIs if the observed PSA level is adjusted to obtain the true PSA level.3 However, anecdotal evidence has led to speculation that 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression is not routinely addressed in the general medical community.4 It is possible that misinterpretation of PSA values in 5-ARI users may lead to delays in diagnosis and worsened cancer-specific outcomes. To our knowledge, there are no data on the association of 5-ARI use with prostate cancer detection and outcomes among men who participate in prostate cancer screening.

We hypothesized that the 5-ARI-induced PSA suppression may lead to delays in prostate cancer diagnosis, higher grade and stage at diagnosis, and higher risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality in a PSA-screened population.

Methods

Data Source

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was conducted using the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), an electronic platform that provides access to patient-level electronic health record information and administrative data for all veterans within the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. VINCI incorporates tumor registry data gathered at individual VA medical centers according to the protocols issued from the American College of Surgeons. We linked VINCI with the National Death Index to obtain cause-specific mortality information (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code C61 for prostate cancer) and with the American Community Survey to obtain zip code income and education. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the San Diego VA health system, which waived informed consent.

Study Population

We identified 82 439 men with stage I to IV prostate cancer with PSA level known at diagnosis between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2015. Patients were required to have at least 2 years’ of prediagnosis medical care at the VA to be included in the cohort. We excluded 1561 patients for unknown information for covariates or cause of death, leaving a final cohort of 80 875 men. Using VA pharmacy data, we identified all patients who were prescribed finasteride or dutasteride at least 1 year before prostate cancer diagnosis. By requiring patients to have started 5-ARIs at least 1 year before diagnosis, we reduced the risk of reverse causality bias, whereby patients are using 5-ARIs to treat the symptoms of imminently diagnosed prostate cancer. Prostate biopsy (Current Procedural Terminology code 55700) date and prebiopsy PSA concentration was available within the data set for a subset of 62 165 patients. All patients were followed up until death or last follow-up with a VA clinician with latest possible follow-up December 31, 2017. Initial data analysis for the present study was performed from March 2018 to May 2018.

Model Building

We extracted the following patient-level variables: age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, race, alcohol history, tobacco history, body mass index, marital status, employment status, and median income and education by zip code. Charlson comorbidity index score was determined from comorbid conditions patients had in the year before diagnosis using previously described methods.5,6,7 We also obtained information on the ever-use of aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, and α-blockers (all until 1 year before diagnosis) from VA pharmacy data.

We collected prostate cancer staging information such as Gleason score, PSA level, and clinical T/N/M stage and treatment-related information such as radiotherapy, surgery, and hormone therapy use. However, we did not include these staging or treatment variables as covariates in our models, because they are on the causal pathway between exposure (prediagnostic use of 5-ARIs) and outcome (prostate cancer–specific mortality).8,9 In essence, controlling for staging or treatment would indirectly control for any hypothesized effect of 5-ARI use. We collected time from elevated PSA (>4 ng/mL in nonexposure group, >2 ng/mL in exposure group) to prostate biopsy in the subgroup of patients with a reported biopsy date. A PSA level of 4 ng/mL was chosen as a threshold because this mark was used in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT)3 and REDUCE trial10 and is commonly used in primary care settings. We used a threshold of 2 ng/mL rather than 4 ng/mL for patients taking 5-ARIs because earlier studies have suggested that doubling the PSA level is necessary to obtain a true PSA level in patients taking 5-ARIs2 and this was the approach taken by the REDUCE trial.10 For 5-ARI users we only included PSA levels drawn after first 5-ARI prescription date.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome of our study was prostate cancer–specific mortality. Secondary outcomes included time from first elevated PSA to diagnostic prostate biopsy, cancer grade and stage at time of diagnosis, and all-cause mortality.

Statistical Analysis

We tested for differences in covariates between exposure groups using χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests when appropriate. We compared unadjusted estimates of prostate cancer–specific mortality and all-cause mortality between 5-ARI users (with or without α -blockers), users of α-blockers only, and patients using neither 5-ARIs nor α-blockers by plotting cumulative incidence curves. We isolated patients who had used only α-blockers (but not 5-ARIs) because of previous commentary that α blockade may confound the association between 5-ARIs and prostate cancer–specific mortality.8,11 Multivariable Fine-Gray competing risk regression models were used to obtain estimates of prostate cancer–specific mortality and noncancer mortality to account for competing risk of death.12 Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to obtain hazard ratio (HR) estimates of all-cause mortality. All models adjusted for the covariates listed in the previous subsection and began evaluating mortality from cancer diagnosis. We evaluated differences in time from elevated PSA to prostate biopsy in a subgroup of patients with reported biopsy date with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Statistical tests were 2-sided, with P < .05 considered significant and were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted 3 sensitivity analyses to determine if our results were robust. First, we varied our time window for starting 5-ARIs or α-blockers from 1 year before prostate cancer diagnosis to 1 month to 1.5 years to 2.0 years. Second, we repeated our survival analysis with the exposure of interest being 5-ARI dose intensity, defined as number of 5-ARI prescriptions (at least 1 year before diagnosis) divided by years of exposure to 5-ARI before prostate cancer diagnosis. Third, we excluded patients with Gleason grade 6 cancer because 5-ARIs are known to suppress these low-grade cancers.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The final cohort included 80 875 patients. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age at diagnosis was 66 (61-72) years, with median (IQR) follow-up of 5.90 (3.50-8.80) years. There were 19 065 all-cause deaths, of which 4513 were from prostate cancer.

A total of 8587 (10.6%) patients were prescribed 5-ARIs at least 1 year before prostate cancer diagnosis; 8406 received finasteride and 181 received dutasteride. Median (IQR) 5-ARI treatment duration before diagnosis was 4.85 (2.60-7.80) years. Patients who received 5-ARI were older, had higher Charlson comorbidity scores, and were less likely to be of black race than nonexposed patients (See Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics at Prostate Cancer Diagnosis.

| Characteristic | Prediagnostic 5α-Reductase Inhibitor Use | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Value | ||

| No (n = 72 288) | Yes (n = 8587) | ||

| Race | <.001 | ||

| Nonblack | 52 196 (72.2) | 6429 (74.9) | |

| Black | 20 092 (27.8) | 2158 (25.1) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 65 (61-71) | 70 (64-76) | <.001 |

| Lifestyle factors | |||

| Alcohol | <.001 | ||

| No | 35 299 (48.8) | 4723 (55.0) | |

| Yes | 36 989 (51.2) | 3864 (45.0) | |

| Tobacco | <.001 | ||

| No | 26 966 (37.3) | 3563 (41.5) | |

| Yes | 45 322 (62.7) | 5024 (58.5) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 51 842 (71.7) | 5383 (62.7) | |

| ≥1 | 20 446 (28.3) | 3204 (37.3) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.9 (24.4-31.8) | 27.6 (24.1-31.5) | <.001 |

| Median income, tertilea | |||

| 1st | 25 421 (35.2) | 3234 (37.7) | <.001 |

| 2nd | 23 618 (32.7) | 2660 (30.9) | |

| 3rd | 23 249 (32.2) | 2693 (31.4) | |

| High school graduation, tertilea | |||

| 1st | 24 992 (34.6) | 3276 (38.2) | <.001 |

| 2nd | 23 643 (32.7) | 2752 (32.0) | |

| 3rd | 23 653 (32.7) | 2559 (29.8) | |

| Employed | <.001 | ||

| No | 58 633 (81.1) | 7450 (86.8) | |

| Yes | 13 655 (18.9) | 1137 (13.2) | |

| Married | <.001 | ||

| No | 35 420 (49.0) | 4029 (46.9) | |

| Yes | 36 868 (51.0) | 4558 (53.1) | |

| α-Blocker | <.001 | ||

| No | 51 792 (71.6) | 1016 (11.8) | |

| Yes | 20 496 (28.4) | 7571 (88.2) | |

| Statin | <.001 | ||

| No | 29 778 (41.2) | 2806 (32.7) | |

| Yes | 42 510 (58.8) | 5781 (67.3) | |

| Nonaspirin NSAID | <.001 | ||

| No | 25 544 (35.3) | 2184 (25.4) | |

| Yes | 46 744 (64.7) | 6403 (74.6) | |

| Aspirin | <.001 | ||

| No | 34 921 (48.3) | 3192 (37.2) | |

| Yes | 37 367 (51.7) | 5395 (62.8) | |

| Diagnosis year | <.001 | ||

| 2001-2005 | 15 962 (22.1) | 1128 (13.1) | |

| 2006-2010 | 30 647 (42.4) | 3512 (40.9) | |

| 2011-2015 | 25 679 (35.5) | 3947 (46.0) | |

| Adjusted pretreatment PSA, median (IQR), ng/mLb | 6.2 (4.6-9.7) | 12.6 (7.6-23.8) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PSA >4 ng/mL at biopsy | <.001 | ||

| No | 19 025 (26.3) | 2492 (29.0) | |

| Yes | 53 263 (73.7) | 6095 (71.0) | |

| Gleason score | <.001 | ||

| NA | 5032 (7.0) | 714 (8.3) | |

| ≤7 | 54 967 (76.0) | 5713 (66.5) | |

| ≥8 | 12 289 (17.0) | 2160 (25.2) | |

| Clinical T stage | <.001 | ||

| 1-2 | 70 213 (97.1) | 8183 (95.3) | |

| 3-4 | 2075 (2.9) | 404 (4.7) | |

| Clinical N stage | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 71 054 (98.3) | 8328 (97.0) | |

| 1 | 1234 (1.7) | 259 (3.0) | |

| Clinical M stage | <.001 | ||

| 0 | 70 169 (97.1) | 8009 (93.3) | |

| 1 | 2119 (2.9) | 578 (6.7) | |

| D’Amico risk stratification | <.001 | ||

| Low | 24 805 (34.3) | 2790 (32.5) | |

| Intermediate | 26 856 (37.2) | 2620 (30.5) | |

| High | 20 627 (28.5) | 3177 (37.0) | |

| Therapy | |||

| Hormone | <.001 | ||

| No | 50 679 (70.1) | 5240 (61.0) | |

| Yes | 21 609 (29.9) | 3347 (39.0) | |

| Radiation | <.001 | ||

| No | 43 380 (60.0) | 5776 (67.3) | |

| Yes | 28 908 (40.0) | 2811 (32.7) | |

| Surgery | .40 | ||

| No | 54 477 (75.4) | 6436 (75.0) | |

| Yes | 17 811 (24.6) | 2151 (25.0) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA from ng/mL to μg/L, multiply by 1.0.

Income and high school graduation tertiles were determined by dividing the cohort into 3 equal-sized groups based on median zip code income and zip code high school graduation rate.

To obtain adjusted PSA we multiplied the PSA for 5α-reductase inhibitor users by 2, per the REDUCE trial,10 to account for PSA suppression by 5α-reductase inhibitors.

Time From Elevated PSA to Biopsy

In the subgroup of patients with recorded time of biopsy, we found that 5-ARI users had longer delays from first elevated (adjusted) PSA to prostate biopsy than patients taking α-blockers alone and patients who used neither α-blockers nor 5-ARIs (median [IQR] years: 5-ARIs, 3.60 [1.79-6.09] ; α-blockers only, 2.11 [0.60-4.18]; neither, 1.17 [0.33-2.92]; P < .001) (Table 2). The unadjusted PSA at biopsy was 6.8 ng/mL for 5-ARI users, 6.4 ng/mL for sole α-blocker users, and 6.4 ng/mL for users of neither (P < .001). The adjusted PSA was approximately twice as high in the 5-ARI group compared with patients receiving α-blockers or patients using neither α-blockers nor 5-ARIs at time of biopsy (5-ARIs, 13.5 ng/mL; α-blockers, 6.4 ng/mL; neither, 6.4 ng/mL; P < .001) (Table 2). When stratifying by age, patients who had used 5-ARIs had their prostate biopsy later than 5-ARI nonusers across all age groups after first elevated PSA (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Time From Elevated PSA to Biopsy and PSA at Time of Biopsy by Medication Status.

| Medication Status | Patients, No. | Median (IQR) | Corrected Median PSA at Biopsy, ng/mLa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years to Biopsy | PSA at Biopsy, ng/mL | |||

| Total cohort | 62 165 | 1.61 (0.42-3.56) | 6.5 (5.0-9.9) | NA |

| 5-ARI nonusers | 55 899 | 1.40 (0.38-3.27) | 6.5 (5.0-9.7) | NA |

| Neither α-blocker nor 5-ARI | 40 001 | 1.17 (0.33-2.92) | 6.4 (5.0-10.4) | NA |

| α-Blocker only | 15 898 | 2.11 (0.60-4.18) | 6.4 (5.1-10.1) | NA |

| 5-ARI ± α-blocker | 6266 | 3.60 (1.79-6.09) | 6.8 (4.7-11.6) | 13.5 |

Abbreviations: 5-ARI, 5α-reductase inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range, NA, not applicable; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA ng/mL to μg/L, multiply by 1.0.

Corrected PSAs for 5-ARI users were calculated by doubling regular PSA value. P < .05 for all comparisons.

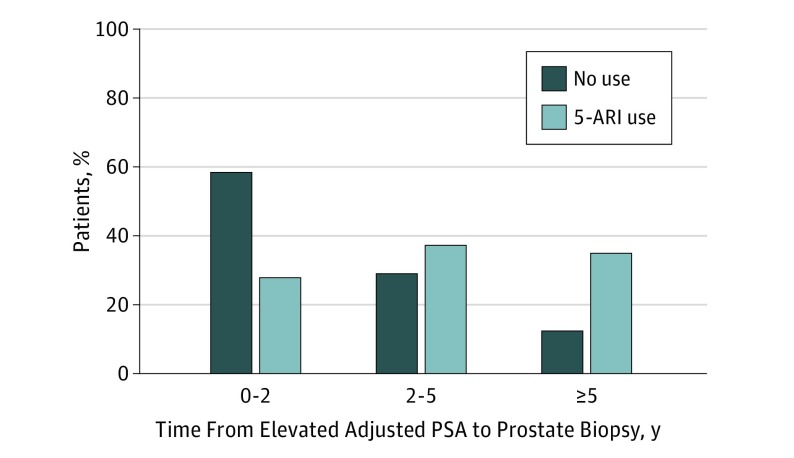

As seen in Figure 1, although 59% of 5-ARI nonusers had their biopsy within 2 years of first elevated adjusted PSA, 29% of 5-ARI users did. Within 5 years of the first elevated adjusted PSA, 88% of 5-ARI nonusers had their prostate biopsy, whereas 65% of 5-ARI users did.

Figure 1. Percentage of Prostate Cancer Diagnoses by Time From Elevated Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Levels to Biopsy.

Adjusted PSA for 5α-reductase inhibitor (5-ARI) users was calculated by multiplying the PSA by 2, per the REDUCE trial, to account for PSA suppression by 5α-reductase inhibitors.10

Disease Characteristics at Diagnosis

5α-Reductase inhibitor users were more likely than nonusers to present with higher grade (Gleason score, 8-10, 25.2% vs 17.0%; P < .001), clinically T3 or 4 (4.7% vs 2.9%; P < .001), clinically node positive (3.0% vs 1.7%; P < .001), and clinically metastatic (6.7% vs 2.9%; P < .001) disease (Table 1). In addition, median [IQR] adjusted pretreatment PSA was significantly higher in 5-ARI users compared with nonusers (12.6 [7.6-23.8] ng/mL vs 6.2 [4.6-9.7] ng/mL; P < .001).

Survival Analyses

The 12-year cumulative incidence of prostate cancer–specific mortality (5-ARI, 13%; α-blocker alone, 8%; neither, 8%; P < .001) and all-cause mortality (5-ARI, 45%; α-blocker alone, 42%; neither, 36%; P < .001) was higher for 5-ARI users compared with patients who had solely used α-blockers and patients who used neither (Figure 2). The multivariable survival analysis can be seen in Table 3. In the Fine-Gray regression model, use of 5-ARIs was associated with a 39% increased risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (subdistribution HR [SHR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52; P < .001). In the multivariable Cox regression, use of 5-ARIs was associated with a 10% increase in all-cause mortality (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05-1.15; P < .001). There were no differences in noncancer mortality (SHR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.01; P = .13). See eTable 2 in the Supplement for noncancer mortality model results.

Figure 2. Unadjusted Cumulative Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality and All-Cause Mortality.

α-Blocker refers to patients who took α-blockers and were not exposed to 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs). 5-ARI refers to 5-ARI users who may or may not have also taken α-blockers. Neither refers to patients who were not exposed to either 5-ARIs or α-blockers.

Table 3. Prostate Cancer–Specific and All-Cause Mortality.

| Characteristic | Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality | All-Cause Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdistribution Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| 5-ARI | ||||

| Yes | 1.39 (1.27-1.52) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.05-1.15) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| α-Blocker | ||||

| Yes | 0.9 (0.84-0.96) | .001 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .07 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Statin | ||||

| Yes | 0.85 (0.80-0.91) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | .02 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Aspirin | ||||

| Yes | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | .31 | 1.18 (1.14-1.21) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| NSAID | ||||

| Yes | 1.06 (0.99-1.12) | .09 | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | .67 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||||

| ≥1 | 1.16 (1.09-1.24) | <.001 | 1.89 (1.83-1.94) | <.001 |

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Married | ||||

| Yes | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | .01 | 0.85 (0.83-0.88) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 0.90 (0.82-1.00) | .05 | 0.86 (0.82-0.91) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Agea | 1.94 (1.86-2.03) | <.001 | 1.96 (1.93-2.00) | <.001 |

| Median income, tertileb | ||||

| 1st | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2nd | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) | .19 | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | <.001 |

| 3rd | 0.99 (0.91-1.09) | .90 | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) | <.001 |

| High school graduation, tertilea | ||||

| 1st | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2nd | 0.99 (0.91-1.07) | .73 | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | .09 |

| 3rd | 0.92 (0.83-1.01) | .07 | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | <.001 |

| Diagnosis yearc | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .003 | 0.92 (0.92-0.93) | <.001 |

| BMId | 0.72 (0.69-0.74) | <.001 | 0.83 (0.82-0.84) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) | .47 | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | .27 |

| Nonblack | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 1.04 (0.97-1.10) | .28 | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | .28 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Tobacco | ||||

| Yes | 1.13 (1.06-1.21) | <.001 | 1.30 (1.26-1.34) | <.001 |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; 5-ARI, 5α-reductase inhibitor; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SHR/HR, subdistribution hazard ratio/ hazard ratio.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA from ng/mL to μg/L, multiply by 1.0.

Subdistribution hazard ratio/hazard ratio estimate for age reflects change in risk of mortality for every 10-year increase in age.

Income and high school graduation tertiles were determined by dividing the cohort into 3 equal-sized groups based on median zip code income and zip code high school graduation rate.

The estimate for diagnosis year represents the SHR/HR for each. additional increase in diagnosis year. For example, being diagnosed in 2011 relative to 2010 results in a 0.01 decrease in risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality, because the SHR is 0.99).

SHR/HR estimate for body mass index reflects change in risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality or all-cause mortality for every 5-point increase in body mass index.

Sensitivity Analysis

Varying the 5-ARI exposure window before cancer diagnosis from 1 month to 1.5 to 2.0 years did not change the prostate cancer–specific mortality or all-cause mortality findings (SHR for prostate cancer–specific mortality 1 month, 1.37; 1.5 y, 1,38; 2 y, 1.41; all-cause mortality, 1 month, 1.11; 1.5 y, 1.10; 2 y, 1.10). Increasing the dose intensity of 5-ARI use increased the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (SHR for prostate cancer–specific mortality: reference, none; low, 1.23; medium, 1.36; high, 1.68; ACM: reference, none; low, 1.01; medium, 1.06; high, 1.31) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). In addition, to ensure that our results were not simply influenced by fewer cases of Gleason grade 6 prostate cancer in the 5-ARI group, we performed a sensitivity analysis which excluded all cases of Gleason grade 6 prostate cancer from either group. Specifically, stage and grade at diagnosis (eTable 4 in the Supplement), time to biopsy (eTable 5 in the Supplement), and survival analyses (eTable 6 in the Supplement) are consistent with the findings of the primary analysis.

Discussion

In this large population-based study, we observed that prediagnostic users of 5-ARIs demonstrated longer times from elevated PSA concentration to diagnostic biopsy, higher adjusted PSA level at diagnosis, higher Gleason score, greater probability of nodal and metastatic disease at presentation, and greater risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality and all-cause mortality.

Anecdotal evidence has led some to speculate that 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression is not routinely addressed in the community and may potentially mask advanced prostate cancer.13 However, to date there have been no objective data on how clinicians in conventional practice address the association of 5-ARIs with PSA level. Our data suggest that PSA suppression in 5-ARI users was not routinely accounted for during prostate cancer screening and led to delays in prostate cancer diagnosis, which in turn may have resulted in advanced disease and worsened clinical outcomes. The unadjusted PSA level at diagnosis was almost identical for 5-ARI users and nonusers despite the more advanced presentation of 5-ARI users. Moreover, in marked contrast to the nonusers, 35% of 5-ARI users had a delay in diagnostic biopsy of more than 5 years after the initial PSA elevation compared with 12% of nonusers.

This analysis does not necessarily suggest that 5-ARI medications are inherently unsafe or that PSA screening is ineffective in men taking 5-ARIs. In fact, multiple analyses from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial have addressed the safety of these medications. The authors reported long-term survival analysis showing no decrement in survival for men taking 5-ARIs.14 A secondary analysis also showed the PSA screening might be even more effective in men taking 5-ARIs.3 However, as part of their study protocols, these trials required strict adjustment of the PSA level because of 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression and recommended an end-of-study biopsy regardless of PSA level, which may not occur in clinical practice. Alternate explanations for our findings should also be considered, including the possibility that 5-ARIs inherently increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer as suggested by the US Food and Drug Administration.15 Or perhaps relief of urinary symptoms from 5-ARIs leads to a delay in referral to a urologist. Finally, it may be that men taking 5-ARIs are more likely to delay or decline further workup or treatment out of personal preference.

This analysis was performed in the VA Health System because of the wealth of information contained in the integrated electronic medical record. However, it is unlikely that these findings are unique to the VA. The Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) trial of dutasteride with or without tamsulosin in men with lower urinary tract symptoms did not mandate PSA level adjustment. In this trial, prostate biopsy rates in men taking dutasteride fell by approximately 40%, largely from a decrease in biopsies for elevated PSA.

One reason that clinicians may not routinely address PSA suppression is that published guidelines do not clearly state the optimal method to adjust for 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression.16,17,18 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Prostate Cancer Early Detection Guidelines note that 5-ARIs decrease the PSA level by approximately 50%. However, the guidelines go on to say that because of the variability in PSA suppression, “the commonly employed method of doubling the measured PSA value to obtain an adjusted value may result in unreliable cancer detection” and that “reflex ranges for PSA levels among patients on 5-ARIs have not been established.”16 The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Urological Association stated that they could not recommend a specific cut point to trigger a biopsy for men taking 5-ARIs.17 Although there is variability in 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression, the PCPT results demonstrate that clear thresholds lead to appropriate biopsy recommendations and improved effectiveness of PSA screening.3

We also believe these data identify an opportunity to build systems-based practices to facilitate accurate interpretations of common laboratory tests affected by medication use. In the context of a busy primary care or urology visit, PSA level adjustment for 5-ARI–induced suppression can be overlooked. In this sense, medication-related clinical decision support tools and laboratory value alert systems are an increasingly useful feature of electronic medical record systems19,20 that could be expanded to adjust for the effects of 5-ARIs.

To date, the data on whether 5-ARIs increase the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality has been mixed. Azoulay et al8 studied a cohort of 13 892 patients with prostate cancer in the United Kingdom, 574 (4.1%) of whom had used 5-ARIs for at least 1 year before cancer diagnosis and found no association of 5-ARI use with prostate cancer–specific mortality. In contrast to the United States, where PSA screening is the most common mechanism of prostate cancer detection, PSA screening is less common in the United Kingdom.21 As such, delayed diagnosis owing to PSA suppression is unlikely to be seen in a UK-based cohort. Ørsted and colleagues11 conducted a population-based study of more than 3 million Danish men and found that men who had taken 5-ARIs had double the risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality as nonusers. However, the association between 5-ARI use and prostate cancer–specific mortality may be confounded by α-blocker use or benign prostatic hyperplasia diagnosis.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the large sample size with up to 16 years of follow-up for assessment of all-cause mortality and prostate cancer–specific mortality. We address several potential sources of bias and important confounders. With VINCI’s longitudinal collection of PSA and biopsy data, we were able to identify a significant diagnosis lag for patients with prostate cancer who had taken 5-ARIs. Finally, our results were robust to a wide variety of sensitivity analyses, including changing the required start date of 5-ARIs before diagnosis, assessing a 5-ARI dose intensity to prostate cancer–specific mortality association and exclusion of Gleason grade 6 disease.

One potential limitation of our study is that 5-ARI–associated delays in diagnosis may appear to worsen prostate cancer–specific and all-cause mortality through lead-time bias. However, a pooled analysis of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) estimated that for each year of delayed detection, the risk of prostate cancer death rose approximately 7% to 9%.22 With a delay in diagnosis of almost 2.5 years for 5-ARI users in our study, the ERSPC-PLCO model would project an increase in prostate cancer mortality of up to 22.5% for 5-ARI users—similar to, albeit modestly lower than, our results. For the purpose of this study, we defined a PSA level greater than 4.0 ng/mL as elevated based on the protocol from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. The optimal threshold for biopsy in clinical practice is debatable and should take other clinical factors into consideration. Second, 5-ARI use was ascertained by receipt of a prescription for finasteride or dutasteride. Thus, misclassification of exposure is possible if patients did not take medication as instructed or received these medications from non-VA clinicians. In addition, we used the National Death Index to obtain cause-specific mortality and thus there may have been misclassification of cause of death. However, there are no indications of differential bias, and death certificates have been shown to accurately reflect prostate cancer–specific mortality rates.23 Given that our source of data are VA records, there may be “co-managed,” dual-enrollment care leading to missing information for some patients. However, this would be unlikely to affect prostate cancer–specific mortality which was derived from the National Death Index. Finally, there may be residual confounding that affects our results, although the equal noncancer mortality between 5-ARI users and nonusers allays some of those concerns. If the 5-ARI users had substantially greater comorbidity or uncontrolled confounders, we would expect them to have greater noncancer mortality, which we did not observe.

Conclusions

Prediagnostic 5-ARI use is associated with delayed prostate cancer diagnosis and worsened prostate cancer outcomes among men in a PSA-screened population. Because 5-ARIs suppress PSA, and adjusted PSA values at diagnosis were twice as high among 5-ARI users as nonusers, these data suggest that adjustment for 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression was not routinely incorporated in this population. Although these results are hypothesis generating, they highlight a continued need to raise awareness of 5-ARI–induced PSA suppression, establish clear guidelines for prostate cancer detection, and motivate systems-based practices to facilitate optimal care for 5-ARI users.

eTable 1. Time from Elevated PSA to Biopsy and PSA at Time of Biopsy Stratified by Age

eTable 2. Non-Cancer Mortality Multivariable Fine-Gray Regression Model

eTable 3. Results of Time Window and Dose Intensity Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Stage and Grade at Diagnosis With Gleason 6 Patients Removed

eTable 5. Time to Biopsy With Gleason 6 Patients Removed

eTable 6. Survival Analysis With Gleason 6 Patients Removed

References

- 1.Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984;132(3):474-479. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)49698-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andriole GL, Guess HA, Epstein JI, et al. Treatment with finasteride preserves usefulness of prostate-specific antigen in the detection of prostate cancer: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. PLESS Study Group. Proscar Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study. Urology. 1998;52(2):195-201. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00184-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson IM, Chi C, Ankerst DP, et al. Effect of finasteride on the sensitivity of PSA for detecting prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(16):1128-1133. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns Hopkins Medicine Brady Urological Institute. Top Prostate Cancer Questions—Finasteride: Are the Risks Worth it? https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/brady-urology-institute/specialties/conditions-and-treatments/prostate-cancer/prostate-cancer-questions/finasteride-are-the-risks-worth-it. Updated December 21, 2019. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 5.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258-1267. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azoulay L, Eberg M, Benayoun S, Pollak M. 5α-Reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer-related mortality in men with prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(3):314-320. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):488-495. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, et al. ; REDUCE Study Group . Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1192-1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ørsted DD, Bojesen SE, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Association of clinical benign prostate hyperplasia with prostate cancer incidence and mortality revisited: a nationwide cohort study of 3,009,258 men. Eur Urol. 2011;60(4):691-698. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh PC. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1237-1238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1001045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the prostate cancer prevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):603-610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theoret MR, Ning YM, Zhang JJ, Justice R, Keegan P, Pazdur R. The risks and benefits of 5α-reductase inhibitors for prostate-cancer prevention. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1106783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Prostate Cancer Early Detection Version 2.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2018.

- 17.Kramer BS, Hagerty KL, Justman S, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology Health Services Committee; American Urological Association Practice Guidelines Committee . Use of 5-α-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1502-1516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901-1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolley CL, Slight SP, Husband AK, Watson N, Bates DW. Improving medication-related clinical decision support. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(4):239-246. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):50-60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams N, Hughes LJ, Turner EL, et al. Prostate-specific antigen testing rates remain low in UK general practice: a cross-sectional study in six English cities. BJU Int. 2011;108(9):1402-1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsodikov A, Gulati R, Heijnsdijk EAM, et al. Reconciling the effects of screening on prostate cancer mortality in the ERSPC and PLCO trials. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):449-455. doi: 10.7326/M16-2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Nelson PS, Barry M, Stanford JL. Determining cause of death in prostate cancer: are death certificates valid? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(23):1822-1823. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.23.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Time from Elevated PSA to Biopsy and PSA at Time of Biopsy Stratified by Age

eTable 2. Non-Cancer Mortality Multivariable Fine-Gray Regression Model

eTable 3. Results of Time Window and Dose Intensity Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 4. Stage and Grade at Diagnosis With Gleason 6 Patients Removed

eTable 5. Time to Biopsy With Gleason 6 Patients Removed

eTable 6. Survival Analysis With Gleason 6 Patients Removed