Abstract

This study analyzes Medicare data from 2015 and 2016 to estimate the percentage of Medicare enrollees who underwent low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer during this period and had participated in a shared decision-making visit to discuss the benefits and risks of the procedure before screening.

In early 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated reimbursement for low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening for lung cancer in individuals aged 55 to 77 years with a 30 pack-year or greater smoking history.1 A unique feature of the CMS approval was a requirement for a separate shared decision-making (SDM) session before the LDCT.1 This visit had several required components, including use of a decision aid and counseling on tobacco abstinence. We used Medicare data from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016 to determine the percentage of enrollees who received an LDCT had a visit for SDM.

Methods

We developed separate cohorts for 2015 (4 192 802 persons) and 2016 (4 138 559 persons) Medicare beneficiaries aged 55 to 77 years with complete Medicare Parts A and B coverage and no health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment from a 20% national sample. Using Current Procedural Terminology codes, we determined the number of enrollees with Evaluation and Management charges for an LDCT SDM visit (Current Procedural Terminology code G0296), and receipt of LDCT (Current Procedural Terminology code G0297 or S8032). We assessed age, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility, region, comorbidities, and education (at the zip code level). The monthly percentage of patients undergoing LDCT with an associated SDM visit were graphed and assessed by joinpoint analysis using joinpoint software downloaded from the National Cancer Institute. Statistical significance for the joinpoint analysis was set at P < .0001. We estimated the odds of patients with LDCT engaging in SDM before the screening and the relative risk of undergoing LDCT after SDM by using logistic regression. These statistical calculations were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). The University of Texas Medical Branch institutional review board approved this study, which used deidentified data.

Results

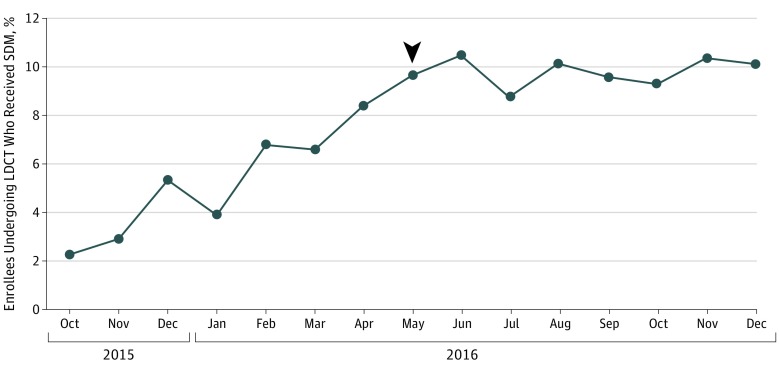

Of the 19 021 enrollees in the 20% sample who underwent LDCT in 2016, 1719 (9.0%) had a separate SDM visit on the day of LDCT or in the previous 3 months. After an initial increase, the monthly percentage of enrollees undergoing LDCT who had participated in SDM plateaued at approximately 10% (Figure). Characteristics associated with lower odds of SDM before LDCT included black race vs white race (odds ratio [OR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59-0.97), female sex (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.98), and higher education (for highest vs lowest quartile of education: OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.96); there was also wide regional variation (Table).

Figure. Percentage of Medicare Enrollees Aged 55 to 77 Years Undergoing Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) Screening Who Had a Shared Decision-Making (SDM) Visit in the 3 Months Before the LDCT.

The denominator for each month is enrollees who underwent LDCT in that month, and the numerator is enrollees who had an SDM visit on the day of the LDCT or in the previous 90 days. Joinpoint analysis revealed a change point (arrowhead) in May 2016 (95% CI, March 2016–July 2016). The slope of the increase for enrollees receiving SDM before May 2016 showed an absolute increase of 1.05% per month. After May 2016, the slope showed an increase of 0.09% per month. Statistical significance for the joinpoint analysis was set at P < .0001.

Table. Characteristics of Medicare Enrollees Aged 55 to 77 Years Who Underwent LDCT Screening for Lung Cancer in 2016 and Had a Shared Decision-Making Visit Regarding LDCT Screening in the Previous 3 Months.

| Enrollee Characteristic | No. of Patients With LDCT (n = 19 021) | Patients With SDM in 3 Months Before LDCT, No. (%) (n = 1719) | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| 55-59 | 1760 | 152 (8.64) | 1 [Reference] |

| 60-64 | 1912 | 189 (9.88) | 1.21 (0.94-1.54) |

| 65-69 | 8229 | 768 (9.33) | 1.16 (0.93-1.43) |

| 70-74 | 5616 | 482 (8.58) | 0.99 (0.80-1.24) |

| 75-77 | 1504 | 128 (8.51) | 0.99 (0.76-1.30) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1203 | 93 (7.73) | 0.76 (0.59-0.97) |

| Hispanic | 445 | 33 (7.42) | 0.74 (0.49-1.11) |

| Others | 688 | 51 (7.41) | 0.87 (0.63-1.19) |

| White | 16 685 | 1542 (9.24) | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9751 | 928 (9.52) | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 9270 | 791 (8.53) | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) |

| Medicaid eligible | |||

| No | 15 268 | 1383 (9.06) | 0.93 (0.79-1.08) |

| Yes | 3753 | 336 (8.95) | 1 [Reference] |

| Region | |||

| New England | 2236 | 89 (3.98) | 1 [Reference] |

| Mid-Atlantic | 2421 | 181 (7.48) | 1.98 (1.50-2.61) |

| South Atlantic | 4507 | 498 (11.05) | 2.96 (2.30-3.79) |

| East North Central | 3118 | 290 (9.30) | 2.25 (1.73-2.93) |

| West North Central | 1547 | 156 (10.08) | 2.79 (2.10-3.71) |

| East South Central | 1656 | 158 (9.54) | 2.42 (1.81-3.23) |

| West South Central | 1221 | 122 (9.99) | 2.65 (1.95-3.58) |

| Mountain | 757 | 110 (14.53) | 4.46 (3.27-6.08) |

| Pacific | 1558 | 115 (7.38) | 1.92 (1.41-2.60) |

| Percentage of patients in zip code area with high school education | |||

| Q1 (≤83%) | 4171 | 400 (9.59) | 1 [Reference] |

| Q2 (84%-89%) | 4147 | 402 (9.69) | 1.03 (0.88-1.20) |

| Q3 (90%-93%) | 4189 | 244 (9.74) | 1.05 (0.89-1.22) |

| Q4 (≥94%) | 4181 | 316 (7.56) | 0.81 (0.68-0.96) |

| Comorbidities, No. | |||

| 0-1 | 7376 | 667 (9.04) | 1 [Reference] |

| 2-3 | 5861 | 551 (9.40) | 1.04 (0.92-1.17) |

| ≥4 | 3451 | 308 (8.92) | 0.98 (0.84-1.13) |

Abbreviations: LDCT, low-dose computed tomography; OR, odds ratio; Q, quartile; SDM, shared decision-making.

ORs were calculated from a logistic regression analysis including all variables shown in the Table.

Of the 2154 enrollees who underwent SDM from January through October 2016, 1300 (60.8%) underwent LDCT in the following 3 months. In a multivariable analysis, black race (risk ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.97) and female sex (risk ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.86-0.99) were associated with significantly lower LDCT use after SDM.

Discussion

Although patient characteristics such as sex, race/ethnicity, and geographical region are associated with receipt of SDM before LDCT and with receipt of LDCT after SDM, the most important finding is the remarkably low uptake of SDM visits after the CMS mandate. Several factors may contribute to this finding, including the recentness of the mandate, lack of training in SDM, and competing priorities for clinicians. In addition, SDM may have occurred as part of another medical encounter.

The CMS has previously issued other requirements on reimbursement for screening tests that also appear to be ignored without affecting reimbursement, for example, on minimum intervals between routine screening colonoscopies in average-risk patients.2

Early reports suggest that less than 5% of eligible Americans are receiving LDCT.3 The 60.8% rate of LDCT after SDM suggests that a substantial proportion of enrollees are deciding against LDCT after SDM.

Our study has some limitations. The results from enrollees aged 65 to 77 years with fee for service Parts A and B Medicare may not be generalizable to those in Medicare HMOs. In addition, the results from enrollees aged 55 to 64 years represent those with disability or end-stage renal disease.

Shared decision-making has rapidly evolved from an abstract concept to mandated implementation. However, the clinical community has not adopted the CMS mandate for an SDM visit before LDCT screening.3 Inability or unwillingness to engage in SDM may contribute to the low overall use of LDCT screening and less awareness of its implications among eligible patients.4,5,6

References

- 1.Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274 Accessed April 26, 2018.

- 2.Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF. Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1335-1343. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M, et al. . Evaluating shared decision making for lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178(10):1311-1316. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ersek JL, Eberth JM, McDonnell KK, et al. . Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and use of low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening among family physicians. Cancer. 2016;122(15):2324-2331. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter-Harris L, Gould MK. Multilevel barriers to the successful implementation of lung cancer screening: Why does it have to be so hard? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(8):1261-1265. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-204PS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1278-1281. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]