Abstract

Importance

Difficulty performing daily activities such as bathing and dressing (“functional impairment”) affects nearly 15% of middle-aged adults. Older adults who develop such difficulties, often because of frailty and other age-related conditions, are at increased risk of acute care use, nursing home admission, and death. However, it is unknown if functional impairments that develop among middle-aged people, which may have different antecedents, have similar prognostic significance.

Objective

To determine whether middle-aged individuals who develop functional impairment are at increased risk for hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This matched cohort study analyzed longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative prospective cohort study of US adults. The study population included 5540 adults aged 50 to 56 years who did not have functional impairment at study entry in 1992, 1998, or 2004. Participants were followed biennially through 2014. Individuals who developed functional impairment between 50 and 64 years were matched by age, sex, and survey wave with individuals without impairment as of that age and survey wave. Statistical analysis was conducted from March 15, 2017, to December 11, 2018.

Exposures

Impairment in activities of daily living (ADLs), defined as self-reported difficulty performing 1 or more ADLs, and impairment in instrumental ADLs (IADLs), defined similarly.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The 3 primary outcomes were time from the first episode of functional impairment (or matched survey wave, in controls) to hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death. Follow-up assessments occurred every 2 years until 2014. Competing risks survival analysis was used to assess the association of functional impairment with hospitalization and nursing home admission and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to assess the association with death.

Results

Of the 5540 study participants (2739 women and 2801 men; median age, 53.7 years [interquartile range, 52.3-55.2 years]), 1097 (19.8%) developed ADL impairment between 50 and 64 years, and 857 (15.5%) developed IADL impairment. Individuals with ADL impairment had an increased risk of each adverse outcome compared with those without impairment, including hospitalization (subhazard ratio, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.77-2.19), nursing home admission (subhazard ratio, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.99-3.45), and death (hazard ratio, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.74-2.45). After multivariable adjustment, the risks of hospitalization (subhazard ratio, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.36-1.75) and nursing home admission (subhazard ratio, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.24-2.43) remained significantly higher among individuals with ADL impairment, but the risk of death was not statistically significant (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.85-1.32). Individuals with IADL impairment had an increased risk of all 3 outcomes in adjusted and unadjusted analyses.

Conclusions and Relevance

Similar to older adults, middle-aged adults who develop functional impairment appear to be at increased risk for adverse outcomes. Even among relatively young people, functional impairment has important clinical implications.

This cohort study uses data from the Health and Retirement Study to determine whether middle-aged individuals who develop functional impairment are at increased risk for hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death.

Key Points

Question

When difficulty performing basic activities of daily living (“functional impairment”) develops in middle-aged adults, is it associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes including hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death?

Findings

In this nationally representative matched cohort study of 5540 community-dwelling adults, those who developed functional impairment between ages 50 and 64 years were at increased risk of hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death compared with those without functional impairment.

Meaning

Even in relatively young people, functional impairment has important clinical implications.

Introduction

The ability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing and dressing is central to older adults’ quality of life and health. When older people develop difficulty performing these activities, often called functional impairment, they experience poorer quality of life and higher rates of acute care use, nursing home admission, and death.1,2,3,4 Thus, a major focus of care for older people is to prevent or slow the progression to functional impairment and its associated adverse outcomes.

Functional impairment is often seen as a problem affecting people 65 years or older and especially the oldest old (≥80 years). However, functional impairment is also common in middle-aged adults. Nearly 15% of adults aged 55 to 64 years have difficulty performing at least 1 ADL,5 a group that includes people with longstanding impairments that are congenital or developed in young adulthood, as well as people with impairments that are newly acquired in middle age. Previous research shows that individuals with longstanding disabilities experience poorer outcomes than individuals without such disabilities.6,7 However, it is unclear if functional impairment that develops for the first time in middle age has the same prognostic importance that it does in older adults. Functional impairment in older adults results from aging-related conditions including chronic illness, frailty, and cognitive impairment.8 Functional impairment that develops in middle-aged people occurs earlier in the life course, before these conditions become highly prevalent. Therefore, some hypothesize that incident functional impairment in middle-aged people may be primarily a transient issue due to acute illness or injury, and thus lacks the prognostic implications of functional impairment that develops among older adults.9

Although few studies have tested this hypothesis, 1 study shows that functional impairment in middle age is associated more strongly with hospital readmission than are chronic conditions,10 while another study shows that functional impairment in middle age is associated with death.11 However, these studies assessed prevalent functional impairment, and thus did not distinguish between longstanding impairments due to trauma or congenital conditions vs impairments that develop in middle age and may have different clinical implications.12 In addition, these studies did not account for potential confounders of the association between function and adverse outcomes, including socioeconomic status and health-related behaviors such as smoking.8

Understanding the clinical implications of functional impairment among middle-aged adults is key to developing appropriate strategies to address these impairments. We used nationally representative, longitudinal data to determine if functional impairment that develops in middle age is associated with hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death, and to examine the strength of the association of function with these outcomes compared with other risk factors.

Methods

Setting and Participants

We analyzed longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing nationally representative panel survey examining changes in health and wealth among Americans older than 50 years.13 The first participants were enrolled in 1992 and additional participants are enrolled every 6 years so the sample remains representative of the population older than 50 years. Participants are interviewed every 2 years by telephone; face-to-face interviews are conducted for those unable to access a telephone or who are too ill to participate by telephone. The institutional review boards of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved this study. Participants provide written informed consent for participation in the HRS; because we used deidentified HRS data for this study, participant consent was waived by the institutional review boards of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Sample

A total of 8430 participants were aged 50 to 56 years at enrollment in the 1992, 1998, or 2004 survey waves and were assessed for study eligibility. For the 1992 wave, we considered the baseline to be 1994, because measures of function collected in 1992 differed from later measures. We excluded 1314 participants who reported difficulty performing ADLs or instrumental ADLS (IADLs) at baseline, 326 unavailable for follow-up after baseline, and 124 with missing functional status data at baseline. We also excluded individuals for whom we could not determine whether an outcome occurred before or after the onset of functional impairment. In each biennial survey wave, participants reported their current function as well as any hospitalizations and nursing home admissions that occurred during the previous 2 years. Thus, if a participant reported both functional impairment and 1 of these events in a single wave, we could not determine which occurred first. We excluded 453 participants who reported a hospitalization or nursing home stay in the same wave or a wave preceding their first impairment, and 15 who were in a nursing home when they first reported impairment. We also excluded 477 participants who first reported impairment in the final wave (2014).

Of 5721 eligible individuals, we identified 1097 who developed functional impairment between 50 and 64 years. To create a comparison group of individuals without impairment before 65 years, we matched these individuals by age, sex, enrollment year, and wave when they reported impairment with individuals without impairment as of that age and wave. For controls who could be matched with multiple individuals who developed functional impairment, we first randomly selected an individual who developed functional impairment. We then used the wave when impairment developed in that individual as the baseline date for the control. This date served as the baseline for time-to-event analyses for both cases and controls. In total, we identified 4624 controls; we excluded 181 who could not be matched. This matching procedure created a cohort balanced by follow-up time and age at first impairment (or matched wave, among controls). We analyzed longitudinal data from these 5540 participants, collected at approximately 2-year intervals, through 2014.

Measures

Factors Associated With Primary Outcomes

We examined 2 primary factors associated with outcomes of hospitalization, nursing home admission, or death: the first episode of ADL impairment between 50 and 64 years, and the first episode of IADL impairment. The HRS uses self-report measures to assess the ability to perform ADLs and IADLs, which have been found to be valid and reliable.14 At each study wave, participants are asked if they have difficulty (yes or no) performing each of 6 ADLs (bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, eating, walking across a room)15 and 5 IADLs (managing money, managing medications, shopping for groceries, preparing meals, making telephone calls).16 We defined ADL impairment as reporting difficulty performing 1 or more ADLs and defined IADL impairment similarly.

Functional impairment among older adults is dynamic and has complex trajectories.17 Although some people have persistent impairment after an initial episode, others improve, although those who improve are at high risk for recurrence.18,19 To examine the association of ADL trajectories with outcomes, we defined a secondary 4-level categorical variable associated with outcomes. We categorized impairment as (1) no impairment between 50 and 64 years, (2) transient impairment, (3) persistent impairment, and (4) recurrent impairment (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). We created a similar variable for IADL impairment.

Outcomes

We examined 3 outcomes: time to hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death. We used self-reported data to define hospitalization and nursing home admission, because participants were aged 50 to 56 years on enrollment and most lacked Medicare claims data. We defined hospitalization as an overnight hospitalization since the last assessment and nursing home admission as an overnight stay since the last assessment, including short stays and stays for long-term care. We determined date of death from the National Death Index and family interviews.

Other Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed at study entry, including self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and educational level; other variables were assessed at the wave when functional impairment was first reported (or the matched wave for controls). Participants reported household income in the previous year; household net worth was calculated based on self-reported assets minus debts. Measures of health status included the following self-reported medical conditions: hypertension, stroke, diabetes, cardiac disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, and arthritis. Participants reported if they had visual impairment (fair or poor eyesight despite best correction) and hearing impairment (fair or poor hearing or use of a hearing aid). We assessed cognitive impairment using a modified version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (with scores ranging from 0 to 35; impairment was defined as a score <5),20 we assessed depression using the 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (with scores ranging from 0 to 8; depressive symptoms were defined as a score ≥3),21,22 and we assessed body mass index as self-reported weight and height.

Measures of health-related behaviors included self-reported alcohol use,23 smoking status, and physical activity; we defined infrequent activity as once weekly or less.24 Measures of health care use and access included self-reported hospitalization 2 years before the wave when functional impairment was first reported and health insurance. Measures of the physical environment included self-reported fair or poor neighborhood safety.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from March 15, 2017, to December 11, 2018. To compare characteristics between participants who developed functional impairment in middle age vs those who did not, we used the t test and the Rao-Scott χ2 test. All analyses accounted for the complex HRS survey design. All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

We used 2 approaches to evaluate each outcome: cumulative incidence during follow-up and time to event. To determine the cumulative incidence of each outcome among participants with or without functional impairment, we used a survival analysis framework; we used this same framework to analyze functional trajectories. To obtain weighted estimates of cumulative incidence, we used a nonparametric competing risks approach accounting for the risk of death25; for the outcome of death, death was the main event with zero competing events. We defined baseline as the wave when a participant first reported functional impairment (or the matched wave in controls), and event time as the date of hospitalization, nursing home admission, or death. Because HRS assessments occur every 2 years, we could not observe the exact date of hospitalization or nursing home admission. We estimated event times to be halfway between the interview date when an event was first reported and the date of the previous assessment. Exact dates of death were available from the National Death Index. We censored participants who ended their observation period or were lost to follow-up.

To compare the risk of each outcome between participants with and participants without functional impairment, we used a survival analysis framework. We used competing risks survival analysis to compare time to hospitalization and nursing home admission between the 2 groups, with death as a competing risk,25 and used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to compare time to death. We first conducted bivariable analyses to examine the association between functional impairment and each outcome. We then conducted multivariable analyses adjusting for functional impairment and traditional risk factors, including sociodemographics, health status, and health-related behaviors. In multivariable analyses, we qualitatively compared the magnitude of association of functional impairment with each outcome with that of other risk factors. We imputed missing variables using the fully conditional specification method. For race/ethnicity, we used the discriminant function method; for other variables, we used the logistic regression method. We created 50 imputed data sets (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). We retained all covariates in the final models. In sensitivity analyses, we used continuous variables for income, net worth, and body mass index, and a 9-level categorical variable for depression. We conducted analyses using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Among 5540 participants, the median age was 53.7 years (interquartile range [IQR], 52.3-55.2 years), 2801 were men, 2739 were women, 4066 were white, and 1113 had less than a high school education (Table 1). A total of 1097 participants (19.8%) developed ADL impairment between 50 and 64 years, and 857 (15.5%) developed IADL impairment. Overall, 390 participants (7.0%) had transient ADL impairment, 411 (7.4%) had persistent ADL impairment, and 296 (5.3%) had recurrent ADL impairment; for IADL impairment, 345 (6.2%) had transient impairment, 291 (5.3%) had persistent impairment, and 221 (4.0%) had recurrent impairment. The baseline characteristics of individuals with ADL impairment differed from those without. Participants with impairment were more likely to be women, racial or ethnic minorities, unmarried, and to have lower socioeconomic status (Table 1). They also had poorer health status and were more likely to smoke, exercise infrequently, and lack health insurance.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of 5540 Participants With or Without Incident ADL Impairment in Middle Age.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (Weighted %)a | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 5540) | ADL Impairment (n = 1097) | No ADL Impairment (n = 4443) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 53.7 (52.3-55.2) | 53.8 (52.5-55.1) | 53.7 (52.3-55.2) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 2739 (46.0) | 604 (51.5) | 2135 (44.7) | .007 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White non-Latino | 4066 (80.2) | 695 (71.9) | 3371 (82.2) | <.001 |

| Black non-Latino | 833 (9.6) | 225 (13.7) | 608 (8.6) | |

| Latino | 501 (7.2) | 144 (10.5) | 357 (6.5) | |

| Other | 139 (3.0) | 32 (3.9) | 107 (2.8) | |

| Married or partnered | 4252 (75.4) | 777 (69.7) | 3475 (76.7) | <.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| <High school education | 1113 (16.2) | 334 (26.7) | 779 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Annual income, quartile, $ | ||||

| ≤32 500 | 1655 (25.5) | 537 (43.2) | 1118 (21.3) | <.001 |

| >32 500 to ≤60 024 | 1504 (25.9) | 264 (24.9) | 1240 (26.2) | |

| >60 024 to ≤98 500 | 1288 (25.3) | 188 (20.0) | 1100 (26.5) | |

| >98 500 | 1093 (23.4) | 108 (12.0) | 985 (26.0) | |

| Net worth, quartile, $ | ||||

| ≤45 000 | 1516 (25.1) | 472 (39.5) | 1044 (21.7) | <.001 |

| >45 00 to ≤137 000 | 1491 (25.6) | 297 (28.1) | 1194 (25.0) | |

| 137 000 to ≤348 500 | 1405 (25.4) | 204 (19.1) | 1201 (26.8) | |

| >348 500 | 1128 (24.0) | 124 (13.4) | 1004 (26.5) | |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||

| Hypertension | 1696 (28.8) | 455 (39.3) | 1241 (26.4) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 95 (1.6) | 44 (4.0) | 51 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 444 (7.4) | 170 (14.7) | 274 (5.7) | <.001 |

| Cardiac disease | 407 (7.0) | 119 (10.6) | 288 (6.2) | <.001 |

| Lung disease | 140 (2.6) | 55 (5.3) | 85 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Cancer | 210 (3.6) | 60 (5.5) | 150 (3.2) | .007 |

| Arthritis | 1498 (25.6) | 474 (43.0) | 1024 (21.5) | <.001 |

| Other health conditions | ||||

| Visual impairment | 707 (12.5) | 251 (22.5) | 456 (10.1) | <.001 |

| Hearing impairment | 589 (10.8) | 166 (15.7) | 423 (9.6) | <.001 |

| Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status score, mean (SD)b,c | 25.0 (2.9) | 23.6 (3.3) | 25.3 (2.8) | <.001 |

| Depression | 829 (15.8) | 283 (27.3) | 546 (12.9) | <.001 |

| Body mass indexd | ||||

| <18.5 | 40 (0.75) | 9 (1.1)e | 31 (0.65) | <.001 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1636 (29.9) | 219 (20.8) | 1417 (32.0) | |

| 25-29.9 | 2274 (42.3) | 390 (36.8) | 1884 (43.5) | |

| ≥30 | 1512 (27.1) | 458 (41.2) | 1054 (23.9) | |

| Alcohol use, ≥3 drinks/d | 525 (11.8) | 100 (10.8) | 425 (12.0) | .37 |

| Current smoker | 1321 (23.4) | 330 (29.9) | 991 (21.8) | <.001 |

| Infrequent physical activity | 3537 (59.6) | 776 (67.3) | 2761 (57.7) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| 1 Wave prior to functional impairment | 855 (15.5) | 257 (24.0) | 598 (13.5) | <.001 |

| ≥2 Waves prior to functional impairment | 792 (13.8) | 207 (18.2) | 585 (12.7) | |

| Uninsured | 662 (11.1) | 206 (18.0) | 456 (9.5) | <.001 |

| Fair or poor neighborhood safety | 660 (9.4) | 220 (17.5) | 440 (7.5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IQR, interquartile range.

Percentages weighted to generate nationally representative estimates and account for the complex survey design. Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding.

Percentage includes those enrolled in 1998 and 2004, as this variable was not available at baseline for participants enrolled in 1992.

Mean scores are reported, rather than percentage of participants with cognitive impairment, because no participants met criteria for cognitive impairment at study enrollment.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Estimate based on fewer than 30 records and thus may have lower reliability.

Cumulative Incidence of Adverse Outcomes

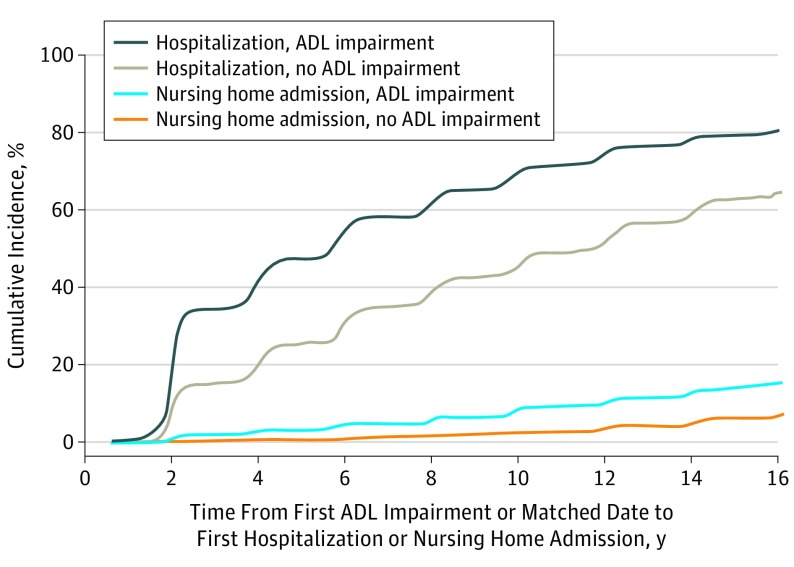

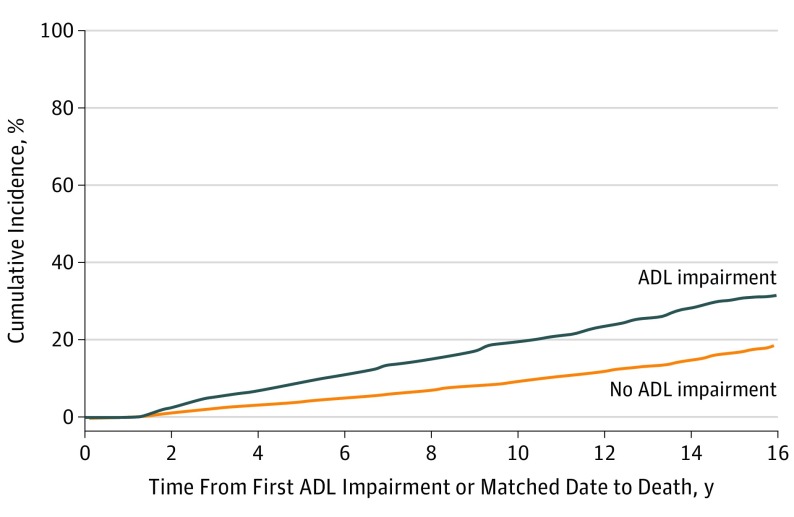

The median follow-up times for adverse outcomes were 6.0 years for hospitalization (IQR, 3.0-10.0 years), 10.0 years for nursing home admission (IQR, 6.5-14.8 years), and 11.4 years for death (IQR, 7.4-15.6 years). The cumulative incidence of each adverse outcome during follow-up was higher among participants with ADL impairment vs those without. Among participants with ADL impairment, the cumulative incidence of hospitalization was 80.8% (95% CI, 76.8%-84.1%) vs 64.7% (95% CI, 62.3%-70.0%) among participants without impairment (Figure 1), the cumulative incidence of nursing home admission was 15.7% (95% CI, 12.1%-19.7%) among participants with ADL impairment vs 7.3% (95% CI, 6.0%-8.9%) among participants without impairment, and the cumulative incidence of death was 31.9% (95% CI, 27.7%-36.1%) among participants with ADL impairment vs 18.7% (95% CI, 16.9%-20.6%) among participants without impairment (Figure 2). Findings for participants with IADL impairment were similar (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Hospitalization and Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-aged Adults With or Without Incident Impairment in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) .

Cumulative incidences of hospitalization and nursing home admission among individuals with or without incident ADL impairment between the ages of 50 and 64 years, determined using a competing risks approach to account for the competing risk of death. Analyses were adjusted to account for the complex survey design. Numbers at risk are not provided because it is not a standard computation for the Fine and Gray model.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Death Among Middle-aged Adults With or Without Incident Impairment in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) .

Cumulative incidence of death among middle-aged adults with or without incident ADL impairment, determined using a competing risks approach to allow for the inclusion of normalized weights; in these analyses, death was the main event with zero competing events. Numbers at risk are not provided because it is not a standard computation for the Fine and Gray model.

Association of Functional Impairment in Middle Age With Adverse Outcomes

Participants who developed ADL impairment in middle age had an increased risk of each outcome, including hospitalization (subhazard ratio [sHR], 1.97; 95% CI, 1.77-2.19), nursing home admission (sHR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.99-3.45), and death (HR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.74-2.45) (Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, the associations with hospitalization and nursing home admission were attenuated, but still statistically significant (sHR for hospitalization, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.36-1.75; sHR for nursing home admission, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.24-2.43). The association with death was not statistically significant after adjustment (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.85-1.32). Participants who developed IADL impairment had an increased risk of all 3 outcomes in adjusted and unadjusted analyses (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses including continuous versions of variables, findings were similar (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Analyses of ADL trajectories showed a generally similar pattern of findings to the primary analyses (eAppendix 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association of Incident ADL and IADL Impairment With Adverse Outcomes Among Middle-aged Adultsa.

| Characteristic | Hospitalization, Subhazard Ratio (95% CI) | Nursing Home Admission, Subhazard Ratio (95% CI) | Death, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |

| Incident ADL impairment | 1.97 (1.77-2.19) | 1.54 (1.36-1.75) | 2.62 (1.99-3.45) | 1.73 (1.24-2.43) | 2.06 (1.74-2.45) | 1.06 (0.85-1.32) |

| Incident IADL impairment | 1.77 (1.57-2.00) | 1.39 (1.19-1.62) | 2.77 (2.02-3.79) | 2.13 (1.48-3.08) | 2.74 (2.33-3.23) | 1.39 (1.12-1.73) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Results weighted to generate nationally representative estimates and account for the complex survey design.

Calculated using competing risks regression for hospitalization and nursing home admission and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for death. All models adjusted for study wave, demographic characteristics (sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status), socioeconomic status (educational level, income, and net worth), health status (chronic medical conditions, visual impairment, hearing impairment, depression, and body mass index), health behaviors (alcohol use, smoking status, and physical activity), prior hospitalization, health insurance (uninsured vs insured), and physical environment (neighborhood safety).

Other Risk Factors for Adverse Outcomes

The associations of ADL impairment with hospitalization and nursing home admission were as strong or stronger than traditional risk factors, including chronic illnesses, obesity, and health-related behaviors (eTables 3-5 in the Supplement). Findings for the association of IADL impairment with hospitalization and nursing home admission were generally similar to those for ADLs (eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement). However, IADL impairment was significantly associated with death (adjusted HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.12-1.73), with an HR similar to the HRs for lower income and net worth, chronic conditions, and health-related behaviors (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this nationally representative study, middle-aged people who developed functional impairment were at increased risk for hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death. After multivariable adjustment, those with ADL impairment remained at significantly higher risk of hospitalization and nursing home admission, but the risk of death was similar to that of individuals without ADL impairment. Individuals with IADL impairment had an increased risk of all 3 outcomes in both adjusted and unadjusted analyses. For most outcomes, developing functional impairment in middle age was as strongly associated with adverse outcomes as traditional risk factors.

A large body of research conducted among older adults shows that functional impairment is strongly associated with hospitalization and nursing home admission, even after multivariable adjustment.1,2,3,4 We found that functional impairment has similar associations in middle-aged adults. Adjusted HRs for the association of functional impairment with hospitalization and nursing home admission were 1.5 to 2.0, similar to those seen in older adults.26,27 Furthermore, these HRs were similar in magnitude to traditional risk factors for the use of health services among middle-aged adults, including chronic illness.28,29 Our findings are consistent with those of a previous study showing that functional impairment in middle age was as strongly associated with hospital readmission as were chronic conditions.10

Among older adults, functional impairment is strongly associated with death, even after multivariable adjustment.3,30 In contrast, among middle-aged adults, functional impairment had mixed associations with death. Middle-aged people with ADL impairment were not at increased risk for death in adjusted analyses, while those with IADL impairment were. It is not clear why functional impairment is associated with death in older adults but not in middle-aged adults. However, our findings reveal differences in the characteristics of functional impairment by age that may influence associations with outcomes. The cumulative incidence of IADL impairment in our cohort was lower than that of ADL impairment, at 15.5% vs 19.8%, consistent with previous research among middle-aged people.31 In contrast, among older adults, a large body of research shows that IADL impairment is more prevalent than ADL impairment.32,33 Among older adults, this pattern is thought to reflect a hierarchical disabling process in which cognitive impairment affects the ability to perform cognitively complex IADL tasks.8,9 In this middle-aged cohort, the lower incidence of IADL impairment may reflect the low prevalence of cognitive impairment. These differing characteristics of functional impairment by age may lead to differing associations with outcomes.

Our findings have clinical implications. Although a large body of research shows function’s prognostic importance among older adults,1,2,3,4 function is seldom routinely assessed in US primary care settings.34,35,36 This disconnect highlights the need to change how we approach function in our patients, from a concept on the sidelines of medical care to a measure as central as chronic illnesses. Although efforts are under way to improve the assessment and management of functional impairment for older adults,37,38 our results suggest that we should consider similar efforts for some middle-aged people. Screening all middle-aged adults for functional impairment is unlikely to be appropriate or cost-effective. However, screening people at high risk for functional impairment may help identify a population at risk for adverse outcomes who would benefit from targeted interventions.

We currently lack evidence-based interventions for middle-aged people who develop functional impairment. However, recent research suggests that, with the exception of cognitive impairment, risk factors for developing functional impairment in middle age are similar to those in older adults, including chronic medical conditions, depression, obesity, and low physical activity.12 Moreover, as in older adults, functional impairment in middle age is multifactorial, with risk factors including health status and health-related behaviors. These similar risk profiles suggest that multifactorial interventions to address risk factors for functional impairment and its sequelae in older adults may hold promise for middle-aged adults,39,40 although additional study is needed to determine how to adapt these interventions for this younger group.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Because we excluded individuals with baseline impairments, our findings are not generalizable to people with longstanding disabilities. We also excluded individuals without follow-up data. Because individuals with functional impairment may have difficulty completing follow-up interviews, our findings may underestimate impairment. However, the HRS interviews participants in person if they are unable to complete telephone interviews, mitigating this issue. We excluded individuals who reported hospitalization or nursing home admission in the same wave or a wave preceding their first impairment. Because hospitalization can precipitate functional impairment, our findings may underestimate the association between impairment and these outcomes. We measured function by self-report rather than objective measures, and could not include physical performance measures because they were assessed in only a small subset of participants. However, self-reported function is a key person-centered measure that is strongly associated with adverse outcomes among older adults.1,2,3,4,41 Because function is assessed every 2 years, shorter periods of impairment may be missed, leading to underestimation of functional impairment.42 Because participants were younger than 65 years on enrollment, we assessed self-reported health care use rather than Medicare claims data. However, self-reported hospitalization is highly correlated with actual hospitalization as measured by claims and medical records, with relatively small reporting errors.43,44,45 Last, while we used matching and multivariable regression to control for differences between people with and people without functional impairment, residual confounding may remain.

Conclusions

We found that functional impairment in middle-aged people is associated with an increased risk for hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death. Even after multivariable adjustment, ADL impairment and IADL impairment remain strongly associated with most of these outcomes, with associations of similar magnitude to traditional risk factors. Our findings suggest that even among relatively young people, functional impairment has important clinical implications. Interventions commonly used to improve and delay functional impairment among older adults may hold promise for improving function and reducing adverse outcomes among middle-aged adults with functional impairment.

eAppendix 1. Association of Functional Trajectories in Middle Age With Adverse Outcomes

eAppendix 2. Approach to Missing Data

eTable 1. Association of Incident ADL and IADL Impairment With Adverse Outcomes Among Middle-Aged Adults, With Adjusted Analyses Incorporating Continuous Variables

eTable 2. Association of Trajectories of ADL and IADL Impairment With Adverse Outcomes Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 3. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Hospitalization Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 4. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 5. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Death Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 6. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Hospitalization among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 7. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 8. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Death Among Middle-Aged Adults

eFigure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Hospitalization and Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults With or Without Incident IADL Impairment

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Death Among Middle-Aged Adults With or Without Incident IADL Impairment

References

- 1.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Functional disability and health care expenditures for older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(21):2602-2607. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the US: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279(15):1187-1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey EC, Walter LC, Lindquist K, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a functional morbidity index to predict mortality in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(10):1027-1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40016.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardener EA, Huppert FA, Guralnik JM, Melzer D. Middle-aged and mobility-limited: prevalence of disability and symptom attributions in a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1091-1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00564.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iezzoni LI. Policy concerns raised by the growing US population aging with disability. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(1)(suppl):S64-S68. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 2):S198-S206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Büla CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(4):445-469. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00370-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Cecchi F, et al. Constant hierarchic patterns of physical functioning across seven populations in five countries. Gerontologist. 1998;38(3):286-294. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.3.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih SL, Gerrard P, Goldstein R, et al. Functional status outperforms comorbidities in predicting acute care readmissions in medically complex patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1688-1695. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3350-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SJ, Go AS, Lindquist K, Bertenthal D, Covinsky KE. Chronic conditions and mortality among the oldest old. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1209-1214. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown RT, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Boscardin WJ, Lee SJ, Steinman MA. Functional impairment and decline in middle age: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):761-768. doi: 10.7326/M17-0496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):576-585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonda S, Herzog AR Documentation of physical functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study and the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old Study. Survey Research Center, University of Michigan. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/dr-008.pdf. Updated December 21, 2004. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 15.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1):20-30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill TM. Disentangling the disabling process: insights from the precipitating events project. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):533-549. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, Gill TM. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(6):575-584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1596-1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitner JC, Welsh KA, Gau BA, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in the National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council Registry of Aging Twin Veterans, III: detection of cases, longitudinal results, and observations on twin concordance. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(8):763-771. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320035011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77-84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly US adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(24):1705-1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He XZ, Baker DW. Body mass index, physical activity, and the risk of decline in overall health and physical functioning in late middle age. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(9):1567-1573. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aliyu MH, Adediran AS, Obisesan TO. Predictors of hospital admissions in the elderly: analysis of data from the Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(12):1158-1167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS. Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):560-578. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putnam KG, Buist DS, Fishman P, et al. Chronic disease score as a predictor of hospitalization. Epidemiology. 2002;13(3):340-346. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Boer AG, Wijker W, de Haes HC. Predictors of health care utilization in the chronically ill: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 1997;42(2):101-115. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(97)00062-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA. 2001;285(23):2987-2994. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller DK, Wolinsky FD, Malmstrom TK, Andresen EM, Miller JP. Inner city, middle-aged African Americans have excess frank and subclinical disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(2):207-212. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spector WD, Katz S, Murphy JB, Fulton JP. The hierarchical relationship between activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):481-489. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90004-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kempen GI, Myers AM, Powell LE. Hierarchical structure in ADL and IADL: analytical assumptions and applications for clinicians and researchers. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(11):1299-1305. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogardus ST Jr, Towle V, Williams CS, Desai MM, Inouye SK. What does the medical record reveal about functional status? a comparison of medical record and interview data. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):728-736. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00625.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(6):451-454. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schor EL, Lerner DJ, Malspeis S. Physicians’ assessment of functional health status and well-being: the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(3):309-314. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430030105012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Meaningful measures hub. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/MMF/General-info-Sub-Page.html. Updated October 25, 2018. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- 38.Nicosia FM, Spar MJ, Steinman MA, Lee SJ, Brown RT. Making function part of the conversation: clinician perspectives on measuring functional status in primary care [published online December 2, 2018]. J Am Geriatr Soc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. ; LIFE study investigators . Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2387-2396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szanton SL, Leff B, Wolff JL, Roberts L, Gitlin LN. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1558-1563. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1839-1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf DA, Gill TM. Modeling transition rates using panel current-status data: how serious is the bias? Demography. 2009;46(2):371-386. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Schmidt L, Jacobsen SJ. Comparison of self-reported and medical record health care utilization measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(9):989-995. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00143-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleary PD, Jette AM. The validity of self-reported physician utilization measures. Med Care. 1984;22(9):796-803. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198409000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217-235. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Association of Functional Trajectories in Middle Age With Adverse Outcomes

eAppendix 2. Approach to Missing Data

eTable 1. Association of Incident ADL and IADL Impairment With Adverse Outcomes Among Middle-Aged Adults, With Adjusted Analyses Incorporating Continuous Variables

eTable 2. Association of Trajectories of ADL and IADL Impairment With Adverse Outcomes Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 3. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Hospitalization Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 4. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 5. Association of ADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Death Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 6. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Hospitalization among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 7. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults

eTable 8. Association of IADL Impairment and Other Risk Factors With Death Among Middle-Aged Adults

eFigure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Hospitalization and Nursing Home Admission Among Middle-Aged Adults With or Without Incident IADL Impairment

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Death Among Middle-Aged Adults With or Without Incident IADL Impairment