Abstract

Epithelioid sarcoma is a very rare tumor, comprising less than 1% of all soft tissue sarcoma. Due to its rarity and benign presentation, it is often misdiagnosed. We present a case of epithelioid sarcoma mimicking coronary artery bypass grafting post-operative keloid. Current literature suggests the management for epithelioid sarcoma to include surgery and adjuvant radiation. In this patient, chest wall reconstruction was done using titanium mesh and muscle flaps. Post-operative radiation was given and computerized tomography scan was evaluated 3 months after reconstruction.

Keywords: Epithelioid sarcoma, keloid, coronary artery bypass graft, chest wall reconstruction, titanium mesh

Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a rare soft tissue tumor that makes up less than 1% of all soft tissue sarcoma.1–4 ES on a cellular level is known to exhibit both epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics.1,2 It was first described under a different name by Laskowski3 in 1961 and was later popularized as epithelioid sarcoma in 1970 by Enzinger,1 a term still commonly used today.

Currently, there are only few literatures on ES. Due to this, there is a need to further study their natural history, pathophysiology and management.5 Superficial ES patient initially presents a lesion, wood-like in consistency.6 These lesions are known to later ulcerate. Due to this initial benign appearance, ES is frequently mistaken for other non-malignant diseases such as keloids, ulcers, abscesses, or infected warts.7 This diagnostic pitfall often causes management delays up to 6 months or even more.8

A study by Sakharpe et al.9 reported that ES has a local recurrence rate of 22%, 16% isolated nodal metastasis rate and 41% distant metastasis rate. Once diagnosed, reports suggested that the standard of care for ES patients is surgical resection with negative margins.10 However, (due to its rarity) strong statistical evidences on the benefit of intraoperative surgical lymph node inspection and post-operative radiation are yet to be published.

Case report

A 52–year-old male came to our outpatient clinic. His chief complaint was a lump on the lower sternal area. The mass was around 10 cm in length, fixated to the sternum. The patient underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) operation 5 years ago. The sternotomy wound appears as a keloid after healing. One year ago, the keloid on the lower sternum increased in size considerably (Figure 1). His initial biopsy showed the tumor as an epidermoid carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Sternal mass during our initial encounter.

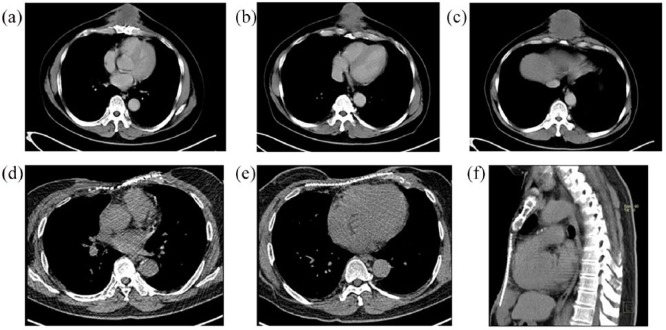

After CABG, there was no complaint of angina pectoris or stroke. The patient has no family history of cancer, did not smoke and was not obese. We performed a thoracic and abdomen computerized tomography (CT) scan; the finding was a mass in the anterior thorax and abdomen, infiltrating both medial side of pectoralis major muscle and rectus abdominis muscle. The sternum was infiltrated, and other intra-abdominal organs were normal. Bone scan was normal.

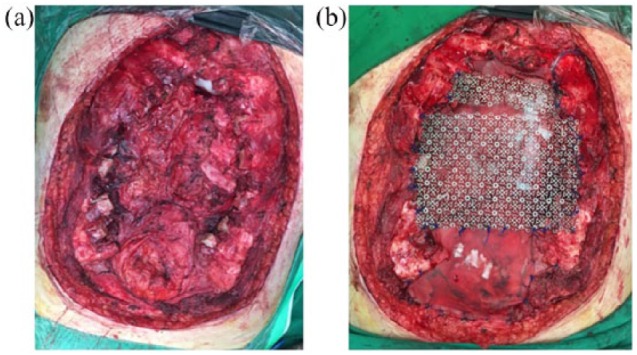

The patient was then planned for surgical management immediately. Intraoperative, wide resection was performed. The sternum was carefully resected with oscillating saw. We ensure that there were no adhesions with the heart and previous CABG grafts (Figure 2). The left internal mammary artery was especially taken into account, ensuring that the reconstruction does not injure or alter the grafts’ course. Sternal drain was placed. The sternum was then reconstructed first using a polypropylene mesh continued with a titanium mesh. Intraoperative frozen section showed that the resection margin is free of residual cancer. A pedicled latissimus dorsi combined with abdominal musculocutaneous flap was used to close the defect. Then, the muscle flap is covered with a split-thickness skin graft.

Figure 2.

(a) Sternum was resected. (b) Reconstruction was done using polypropylene and titanium mesh. Muscle flap was added afterwards.

The patient was discharged 10 days post surgery. Immunohistochemistry showed epithelioid sarcoma. The patient’s treatment was continued with post-operative radiation. The total radiation dose given was 60 Gy. Three months after reconstruction, the patient was evaluated with CT scan (Figure 3). During the 3 months follow-up, the patient does not have any complaint of dyspnea or chest pain and he is able to complete the 6 min walk test. We did not do any spirometry test in this patient. He is currently on medication to control his high blood pressure, but he is able to perform his daily activities.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Computerized tomography scan showing the extend of the sternal mass prior to reconstruction. (d–f) Computerized tomography scan 3 months after reconstruction with titanium mesh.

Discussion

There had been previous case reports misdiagnosing sarcoma for keloid scars.10 In this case, previous CABG made it even more challenging. It was reported by the previous care giver that initially the tumor mimicked post CABG keloid. As previously mentioned, surgery is currently the standard of care for ES patients. However, there is an ongoing debate for lymph node inspection and post-surgical radiation.11 In our case, due to previous CABG adhesion mediastinal lymph nodes were not evaluated.

Intraoperatively, wide excision and sternal resection need to be done carefully not causing iatrogenic trauma, but still adhering to the principles of surgical oncology. Furthermore, we have to ensure that our reconstruction efforts is in harmony with previously placed CABG grafts and our titanium mesh does not hinder or alter the natural course of the grafts.

Lungs, brain, bone and peritoneum are organs reported for distant metastasis.9 In this case, thoraco-abdominal multislice CT (MSCT), bone scan and clinical evaluation by neurologist were done before surgery to rule out distant metastases. Looking back, preoperative positron emission tomography (PET)–CT can be of value for this particular case, as it can also show mediastinal lymph node involvements better.

In regards to post-surgical radiation, most reports have a small sample size, making it difficult to assess the benefit of post-surgical radiation. In the current literature, most patients received post-operative radiation therapy. This is partly because physicians opted to manage ES using general guidelines for sarcoma. A report noted that 71% patients remained disease-free after post-operative radiation while there is a 50% rate of recurrence for patients with post-surgical chemotherapy.5 Other studies by Callister12 and Livi13 also suggest that post-operative radiation for ES provides some benefit from local recurrence.

Conclusion

Benign appearance and rarity of ES contribute to diagnostic delays. Once diagnosed, surgery with post-operative radiation needs to be done in resectable early stage cases. In our case, previous CABG further obscures the initial diagnosis and makes the operation more technically difficult. During resection and reconstruction extra effort was needed to ensure that there was no iatrogenic trauma while still adhering to the principles of surgical oncology.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval is not required in our institution for reporting individual cases.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for anonymized patient information to be published in this case report.

ORCID iD: Harvey Romolo  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1284-2099

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1284-2099

References

- 1. Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma. A sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer 1970; 26: 1029–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Molenaar WM, DeJong B, Dam-Meiring A, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma or malignant rhabdoid tumor of soft tissue? Epithelioid immunophenotype and rhabdoid karyotype. Hum Pathol 1989; 20: 347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laskowski J. Sarcoma aponeuroticum. Nowotory 1961; 11: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer 2006; 107: 606–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guzzetta AA, Montgomery EA, Lyu H, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: one institution’s experience with a rare sarcoma. J Surg Res 2012; 177(1): 116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chase DR, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma: diagnosis, prognostic indicators, and treatment. Am J Surg Pathol 1985; 9: 241–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rastrelli M, Mosconi M, Tosti G. Epithelioid sarcoma of the thumb presenting as a periungual warty lesion: case report and revision of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011; 64: e221–e222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bos GD, Pritchard DJ, Reiman HM, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma. An analysis of fifty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70: 862–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sakharpe A, Lahat G, Gulamhusein T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma and unclassified sarcoma with epithelioid features: clinicopathological variables, molecular markers, and a new experimental model. Oncologist 2011; 16(4): 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nicholas RS, Stodell M. An important case of misdiagnosis: keloid scar or high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma? BMJ Case Rep. Epub ahead of print 4 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pradhan A, Cheung Y, Grimer R, et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the hand: oncological outcome and prognostic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Callister MD, Ballo MT, Pisters PW, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: results of conservative surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 51: 384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Livi L, Shah N, Paiar F, et al. Treatment of epithelioid sarcoma at the Royal Marsden hospital. Sarcoma 2003; 7: 149–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]