Abstract

The Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium identified four gene expression consensus molecular subtypes, CMS1 (immune), CMS2 (canonical), CMS3 (metabolic), and CMS4 (mesenchymal), using multiple microarray or RNA-sequencing datasets of primary tumor samples mainly from early stage colon cancer patients. Consequently, rectal tumors and stage IV tumors (possibly reflective of more aggressive disease) were underrepresented, and no chemo- and/or radiotherapy pretreated samples or metastatic lesions were included. In view of their possible effect on gene expression and consequently subtype classification, sample source and treatments received by the patients before collection must be carefully considered when applying the classifier to new datasets. Recently, several correlative analyses of clinical trials demonstrated the applicability of this classification to the metastatic setting, confirmed the prognostic value of CMS subtypes after relapse and hinted at differential sensitivity to treatments. Here, we discuss why contexts and equivocal factors need to be taken into account when analyzing clinical trial data, including potential selection biases, type of platform, and type of algorithm used for subtype prediction. This perspective article facilitates both our clinical and research understanding of the application of this classifier to expedite subtype-based clinical trials.

Keywords: consensus molecular subtypes, clinical trials, biomarkers, stratification, gene expression, personalized medicine

Key Message

Colorectal cancer consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) may represent potential biomarkers for prospective patient stratification in biomarker-enriched clinical trials. Multiple contexts and possible equivocal factors must be considered to realistically predict each subtype’s incidence during sample size estimation and ultimately to design and implement successful clinical trial stratification.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is highly heterogeneous at the genomic and transcriptomic levels [1]. Only a few genomic biomarkers, namely microsatellite instability (MSI) and extended RAS and BRAF mutational status, are routinely used for prognostication and treatment prediction in clinical practice [2, 3]. Although several multi-gene assays such as Oncotype DX, ColoPrint and ColDX have demonstrated independent prognostic value in early-stage CRC, their use is currently not recommended by international guidelines due to unclear clinical utility over current risk stratification factors and due to the lack of value in predicting treatment benefit [3]. Whether gene expression signatures add clinically relevant information to existing clinical subgroups in early or advanced stages is controversial.

Using a network-based approach to match six distinct classifiers, we, along with other members of the CRC Subtyping Consortium (CRCSC), identified four robust consensus molecular subtypes (CMS): CMS1, enriched for inflammatory/immune genes; CMS2, canonical; CMS3, metabolic; and CMS4, mesenchymal [4]. Stage-independent prognostic value and significant associations with multiple clinical and biological features were demonstrated. These data were subsequently validated in multiple retrospective analyses of prospectively collected clinical trial samples [5–8]. Our group also demonstrated the potential predictive value of molecular subtypes with respect to the FOLFIRI (a combination of 5-flurouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan) chemotherapy regimen and the anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted agent cetuximab using our previously published subtype classifier (CRCAssigner) that is now reconciled into the CMS subtypes [9]. Similar findings have been described in cell lines and retrospective clinical cases by others [10, 11]. Recently, the CMS subtypes were evaluated as independent prognostic factors of survival demonstrating consistent results in correlative studies of phase III clinical trials (Table 1); however, conflicting results were shown when tested as predictive factors of benefit from standard treatments in the metastatic setting [5, 6]. Therefore, although the CMS subtypes show real promise for patient stratification to guide new biomarker-enriched clinical trials, a number of potential flaws and challenges must be accounted for when retrospectively analyzing studies or designing new ones. An in-depth contextual analysis of each study will help better understand the potential clinical usefulness of this new classifier. In addition, a precise estimate of biomarker prevalence in a specific clinical context is fundamental to define the target population and the distribution of each subtype. Incorrect estimates may result in unsuccessful screening efforts, wasted resources, and possibly even disadvantage to patients. In this perspective article, we compare several features of the original CRCSC population with recently published data and publicly available datasets to highlight context-specific subtype characteristics and important equivocal factors to ultimately facilitate realistic application by the oncology community.

Table 1.

Consensus molecular subtypes analyses done in randomized clinical trials

| Study name | Study design | Clinical analysis type | Setting | No of sample | Sample source | Platform | Subtyping algorithm | Major findings | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PETACC-3 | 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) and leucovorin ± irinotecan | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | Adjuvant | 688 | Primary tumor | Almac Affymetrix ADXCRC (Craigavon, Northern Ireland) | Network analysis and random forest | CMS is prognostic | Van Cutsem et al. [21] and included in Guinney et al. [4] |

| NSABP C-07 | 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin ± oxaliplatin | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | Adjuvant | 1729 | Primary tumor | NanoString (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) | SSP | CMS is prognostic CMS2—(sub-subtype enterocyte from CRCAssigner) showed potential association with oxaliplatin benefit | Song et al. [27] |

| PETACC-8 | FOLFOX ± cetuximab | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | Adjuvant | 1779 | Primary tumor | NanoString (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) | NA | CMS is prognostic | Marisa et al. [8] |

| CALGB/SWOG 80405 | Chemo + cetuximab versus Chemo + bevacizumab | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | First line | 581 | Primary tumor | NanoString (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) | NA | CMS is highly prognostic CMS1 possibly benefits from anti-VEGF versus anti-EGFR therapy | Lenz et al. [5] |

| FIRE-3 | FOLFIRI + cetuximab versus FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | First line | 313 (RAS wt) 119 (RAS mt) | Likely primary tumor | Almac XcelTM array (Craigavon, Northern Ireland) | NA | CMS is highly prognostic CMS4 possibly benefits from anti-EGFR versus anti-VEGF therapy | Stintzing et al. [6] |

| AGITG MAX | Capecitabine versus capecitabine + bevacizumab (±mitomycin) | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | First line | 237 | Primary tumor | Almac XcelTM array (Craigavon, Northern Ireland) | SSP (predicted and nearest) | CMS is highly prognostic CMS2 and possibly CMS3 benefits from anti-VEGF therapy | Mooi et al. [7] |

| CORRECT | Regorafenib versus placebo | Correlative analysis of phase III trial | chemorefractory | 281 | Archival tumor tissue | Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST array (Santa Clara, California, USA) | NA | No PFS or OS difference between subtypes | Teufel et al. [22] |

| Oslo Co-Met | Laparoscopic versus open liver resection | Correlative analysis of interventional trial | Metastatic (liver) | 46 | Liver metastases | Agilent SurePrint G3 (Agilent SurePrint, Santa Clara, California, USA) | NA | Limited applicability of CMS on liver metastatic samples | Østrup et al. [17] |

PETACC-3, Pan European Trial Adjuvant Colon Cancer - 3; NSABP-C07, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project - C07; PETACC-8, Pan European Trial Adjuvant Colon Cancer - 8; CALGB/SWOG, Cancer and Leukemia Group B/Southwest Oncology Group; FIRE-3, FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer; AGITG MAX, Australian Gastrointestinal Trials Group MAX Trial (Mitomycin, Avastin, Xeloda); CORRECT, Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer; Oslo Co-Met, Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases.

Context 1: stage

In the CRCSC analysis, the biological characteristics of a subset of the samples were analyzed. The vast majority (2715/2952; 92% of samples with available information) were representative of early-stage tumors at diagnosis, the remaining 8% of samples belong to patients diagnosed with stage IV disease [4]. In developed countries, up to 30% of CRC patients have metastatic disease at diagnosis [12]. Therefore, this population is underrepresented in the CRCSC analysis, and this factor must be taken into account when applying the CMS classification to the metastatic setting. As an example, CMS4 enrichment could be expected in advanced stage tumors, and this requires consideration when designing a study that prospectively selects or stratifies patients for particular subtypes. Furthermore, it is plausible to consider reclassifying advanced stage tumors de novo; new subtypes with activated expression pathways different from early stage tumors could be identified.

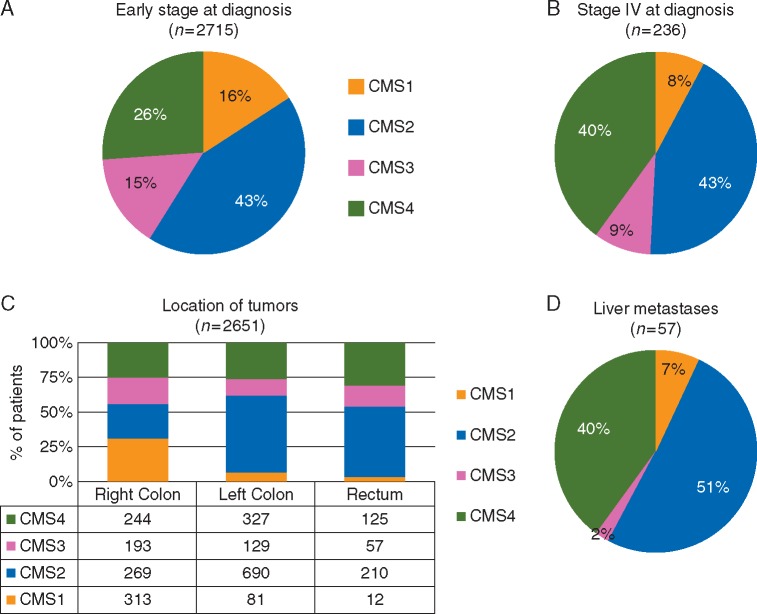

With this limitation in mind, Figure 1A and B shows the different CMS distributions in early and metastatic diseases at diagnosis from the original CRCSC dataset [4]. The poor prognostic CMS4 group is enriched in the advanced setting, while the MSI-enriched subtypes (predominantly CMS1 and partially CMS3) are of low prevalence in the same setting [13].

Figure 1.

(A and B) The proportions of each consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) colorectal cancer (CRC) subtype in (A) early stage (I–III) at diagnosis, (B) stage IV at diagnosis, and (C) location of the tumors within the CRCSC dataset and (D) liver metastatic samples from the publicly available Khambata-Ford dataset [14].

Context 2: sample source

The CRCSC dataset was built from multiple datasets limited to primary tumor samples. While the majority of samples were from the colon, 15% of samples were rectal cancers, probably because rectal tumors are more frequently treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy so are not included in untreated datasets. With this caveat, the proportion of the four subtypes in the rectum was very different from those arising in the colon, with only 12 samples (0.1% of total) belonging to CMS1 (Figure 1C). Conversely, the CMS1 subtype predominated in tumors arising on the right-sided colon, in line with the high prevalence of MSI and BRAF mutant tumors at this site. A similar variable distribution between the right and left colon (which also included rectal samples) was further confirmed in a correlative analysis of the FIRE-3 clinical study in the first-line setting (6).

In another example, we demonstrated that CRC liver metastases could be classified according to CRC subtypes (developed using primary tumor samples) by applying the CRCAssigner classifier to publicly available data from the Khambata-Ford dataset [9, 14]. Here, we reclassified the same dataset using the CMS algorithm [4]. In Figure 1D, we show the subtype distribution after removal of 29% of the mixed/undetermined samples. While the proportion of CMS2 is similar to that found in the left colon (more frequently metastatic to the liver via the hepatic portal system), CMS4 replaces the majority of CMS1 and CMS3. This is in line with the peritoneum (instead of the liver) being the preferential site of relapse for BRAF-mutant (CMS1) and mucinous tumors [15, 16]. Surprisingly, despite mutant KRAS being identified in 30 out of 80 patients, only 1 patient (2%) was classified as CMS3. This depletion of CMS3 was recently confirmed in the Oslo Co-Met trial molecular analysis, where, out of 44 samples, no CMS3 tumors were identified but 68% were classified as CMS2 [17]. Whether this is an effect of chemotherapy-induced molecular changes in the liver or an intrinsic biological characteristic of this subtype requires further analysis. Also, the tolerogenic hepatic microenvironment maintained by immunosuppressive cytokines interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (CMS4-activated pathway) may potentially interfere with subtype classification [4, 18]. Particular caution and further validation studies are required especially in consideration of the fact that the CMS subtypes were developed in the context of primary CRC and its applicability to metastatic tissues (including those from liver, lung and peritoneum) has not yet been fully established.

Lastly, in recent analyses, Dunne et al. demonstrated discordant subtyping results from different tumor areas potentially due to intra-patient heterogeneity and/or differentially expressed stromal genes [19]. The same authors also questioned the robustness of CMS subtypes in tissue biopsies, demonstrating a high proportion of unclassified samples [20]. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity and sampling errors remain major open challenges. The concordance between biopsies and resection specimens was not considered in the original CRCSC dataset, highlighting again how sample source needs to be carefully selected for each patient for robust biomarker assessment.

Context 3: trial versus off-trial, first-line, and chemorefractory settings

Only one dataset was related to a clinical trial (PETACC-3) in the CRCSC study [4, 21]. Trial inclusion criteria usually exclude patients with poor performance status, comorbidities, or heavily symptomatic conditions, leading to underrepresentation of patients with high disease burden and/or aggressive disease. Conversely, retrospective series may often harbor hidden selection bias. Recently, at least three clinical trials in the first-line setting with similar inclusion criteria (CALGB 80405, FIRE-3, and AGITG MAX) were presented at international conferences [5–7]. The CMS subtype distribution was consistent across studies, and the proportion of subtypes in these trials from the metastatic setting was unexpectedly similar to the proportion of early-stage subtypes in the CRCSC study, which was predominantly off-trial. Surprisingly, nearly 80% of patients enrolled in CALGB/SWOG 80405 had synchronous metastases at diagnosis of the primary tumor. Given that some patients with stage IV disease at diagnosis do not receive palliative primary tumor resection, the primary tumor sample may not have been available for correlative studies. On the other hand, it is more likely that the primary tumor was available for patients with early-stage disease at diagnosis. Extensive publications of these analyses including comparisons with the original study population are eagerly awaited.

With respect to the chemorefractory setting, a preliminary analysis of CMS subtypes in a subset of patients (281/760; 37%) enrolled in the CORRECT trial (regorafenib or placebo in patients progressing to standard chemotherapy) was presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting 2015 [22]. The predominant subtype in this heavily pretreated population was CMS2 (50%) followed by CMS4 (30%), while CMS1 and CMS3 were less represented at 9% and 11%, respectively. The relatively consistent subtype distribution in the first-line trials may explain the enrichment of CMS2 and CMS4 over CMS3 and CMS1 after relapse in chemorefractory setting. Only patients with favorable tumor biology after relapse are likely to reach the chemorefractory setting and maintain the fitness to be enrolled in clinical trials. Extensive analysis of the full CORRECT or similar trials is warranted to address the above hypothesis.

Context 4: enrichment by genomic or clinical variables

As discussed above, there exist significant associations between certain CMS subtypes and genomic, clinical, and pathological variables, e.g. BRAF mutations, MSI, high histological grade, and female gender with CMS1; RAS mutations with CMS3; and advanced stages with CMS4. Therefore, subtypes distribution may be modified by genomic or clinical selection criteria. In fact, in the FIRE-3 analysis presented recently, different proportions of CMS3 (11% in KRAS wild-type versus 25% in KRAS mutant population) and CMS2 (41% versus 27%) were shown when KRAS wild-type and mutant patients were analyzed separately. Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in the proportion of CMS1 and CMS4 [6]. Therefore, during the design of molecularly selected clinical trials, the variables used as inclusion criteria may affect the subtype distribution. Hence, this factor needs to be taken into consideration for clinical trial design.

Equivocal factor 1: different methods of predicting CMS subtypes

Two different algorithms for CMS classification are available on-line in the R ‘CMSclassifier’ package: one suitable for population-based studies (random forest classifier) and one suitable for single-sample prediction (Pearson correlation-based classifier, SSP) (4). The random forest classifier uses both different default normalization and a different gene set to that of the SSP classifier. Both provide two distinct subtyping results. First, the ‘predicted CMS’ output includes the mixed/undetermined subtype along with the four CMS subtypes. This classifier was used in reporting the performance (such as sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values) described in the original publication. The second is the ‘nearest CMS’ output, where each sample from the undetermined/mixed group is forced into one of the four CMS subtypes based on the dominant signature. Up to 13% CRCSC samples were labeled as mixed/undetermined since they did not classify into any of the four subtypes and did not represent a potentially distinct subtype. These may partially represent low-quality samples; however, the majority of them are thought to represent intra-tumoral heterogeneity, with more than one subtype present in the same sample.

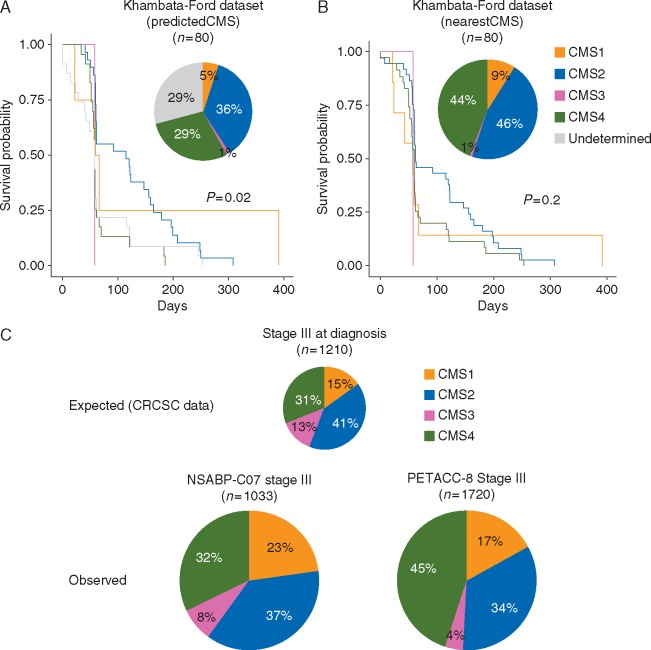

In order to understand whether the single-sample predictor ‘predicted’ or ‘nearest’ CMS subtype classifications affect prognostication and prediction, we applied both to the well-used Khambata-Ford dataset of metastatic patients treated with anti-EGFR therapy [14]. Using the ‘predicted CMS’ subtyping, up to 29% of the samples (n = 23) remained mixed/undetermined (Figure 2A), twice that of the CRCSC population (13% mixed/undetermined). This may be attributed to the change in microenvironment from the primary to secondary site (liver) or may represent a technical artifact.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Pie charts distribution and Kaplan–Meier survival analyses for cetuximab progression-free survival in the Khambata-Ford dataset [14] according to (A) predicted consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) subtype and (B) nearest CMS subtype. (C) The proportions of each CMS in stage III colorectal cancer samples from the CRCSC dataset (top), the NSABP-C07 ancillary study (left bottom, modified from previous publication [15]), and the PETACC-8 ancillary study (right bottom, modified from previous publication [8]).

Conversely, using the ‘nearest CMS’, 52% (n = 12) of the previously mixed/undetermined 29% samples were classified as CMS4. This subtype is enriched for mesenchymal and stromal gene signatures, which may be derived from surrounding cells rather than being cancer specific. Further, 35% (n = 8) were classified as CMS2 (the most heterogeneous group). Interestingly, no samples were relabeled as CMS3, again potentially due to liver microenvironment or suggesting that the mixed/undetermined group may include dominant CMS4 and CMS2 subtypes. Recently, a new algorithm (CMScaller) optimized to apply the CMS classification to pre-clinical models demonstrated 83% prediction accuracy in primary CRC patient samples [23]. Based on cancer cell intrinsic signals, the authors did not yet recommend its implementation in samples different than primary tumor resection specimens.

These examples highlight how the choice of which CMS predictor algorithm to use is crucial and the applicability of each algorithm may be limited in certain contexts. While the majority of publications have been based on single-sample predictor ‘predicted CMS’, quite a few use the ‘nearest CMS’ [24]. We believe that the use of predicted versus nearest CMS may have different consequences. For example, using the nearest CMS rather than the predicted CMS loses the power to define significant benefit from cetuximab treatment according to subtypes in the Khambata-Ford dataset (Figure 2B). When mixed/undetermined samples are forced into a CMS group, they cannot be distinguished from those with a definite CMS class and may confound the result. This is likely to negatively impact on the performance of the classifier and potentially mislead investigators.

Equivocal factor 2: additional heterogeneity leading to sub-classification

The proportion of canonical CMS2 subtype is the same in both the early and advanced settings. Although not strongly associated with any of the common actionable genomic events in CRC (such as RAS/BRAF mutations or MSI), this is possibly the most heterogeneous gene expression subtype. In fact, CMS2 includes two of our original CRCAssigner subtypes (enterocyte and Transit-Amplifying or TA) and three Marisa subtypes (C1, C5, and C6) [4, 9, 25]. We and others demonstrated diverse responses to anti-EGFR therapy in the TA subtype [9, 10]. More recently, in an intra-tumoral heterogeneity-based analysis (in a small cohort of patient samples), we suggested that the presence of TA sub-clones even in non-TA tumors is associated with anti-EGFR therapy response [26]. Similarly, potential differences in benefit between subtypes with and without oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy (survival benefit in enterocyte versus the others) were suggested in an exploratory analysis of the NSABP-C07 trial; however, this was not statistically significant in the validation cohort, although similar trends were observed [27]. This heterogeneity was less visible using the CMS classifier in the same cohort. Therefore, it may be reasonable to subdivide the CMS2 to further understand biological heterogeneity, stage distribution, and potential personalized targets of this subtype. Similarly, in the PETACC-8 subtype analysis, the authors demonstrated significantly different prognostic value when the CMS4 subtype was further subdivided into CMS4-C4 (worse DFS and OS) and CMS4-not C4, based on Marisa classification [8]. More recently, the same authors demonstrated how 57% of 1779 profiled PETACC-8 samples showed intra-tumor heterogeneity assessed using an in-silico deconvolution algorithm and this heterogeneity was an independent predictor of relapse [28]. These examples highlight how CMS subtypes define the overall profiles of major CRC subgroups; however, even within each subtype, there may be biological variability and important sub-subtypes with distinctive clinical/biological parameter that requires careful consideration.

Equivocal factor 3: different platforms, gene sets, and assays

The CRCSC analysis was originally performed using gene expression data derived from multiple platforms including Affymetrix and Agilent microarrays, and RNA-sequencing [4]. In order to accommodate a broader set of platforms, the consortium combined classifiers trained on different platforms to classify samples into CMS subtypes, thereby favoring the portability of the classifier across platforms and maintaining high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Additionally, by virtue of good concordance of the nCounter platform (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) across multiple cancer types [29–31], several groups including us have used this platform and a variable number of genes to assay for subtypes [5, 8, 25, 32].

Initially, we selected a robust set of genes (n = 38) able to classify samples into our CRCAssigner subtypes (originally developed using 786 genes). We then optimized a low-cost protocol for nCounter platform and validated the results using matched RNAseq/microarray platform results [32]. After the CRCSC collaboration, we further developed this assay to simultaneously classify samples into both CRCAssigner and CMS subtypes [33]. We then demonstrated how the concordance between CRCAssigner and CMS classifiers using the nCounter platform was maintained as per the multiplatform CRCSC network.

Therefore, by virtue of the portability of the classifier initially demonstrated by CRCSC and then validated by us, the type of platform used is unlikely to affect the classification. However, the number of genes in each assay and each gene’s contribution may affect the subtype prediction and can explain differences between studies.

The NSABP-C07 correlative study demonstrated a significant recurrence-free survival advantage by adding oxaliplatin to fluorouracil-leucovorin adjuvant therapy for the enterocyte subtype but not for the other subtypes [27]. In this study, the authors used a custom nCounter platform assay (Colo-295), which was designed before the publication of the CRCAssigner and CMS gene expression subtypes. Up to 72 genes overlapped with our original CRCAssigner-786 set. Similarly, the CMS subtypes were defined based on 37 overlapping genes with the original 693 consensus genes. The CMS subtype distribution in this cohort demonstrated enrichment for CMS1 (23%) and depletion of CMS3 (8%) compared with the stage III CRCSC cohort (Figure 2C) [4, 27].

A similar correlative phase III randomized trial in the same setting (oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab in patients with resected stage III colon cancer; PETACC-8) was presented recently, with the extended publication awaited [8]. The NanoString assay was developed using computational approaches and matched frozen and FFPE samples before being tested on a larger scale using the RNA extracted from the PETACC-8 tissue biobank. Again, when compared with the stage III CRCSC population, there was a significantly lower proportion of the CMS3 subtype (only 4%) and marked enrichment for CMS4 (45%). Similarly, when comparing subtype distribution between the KRAS exon 2 wild-type population in the correlative analyses of CALGB 80405 and FIRE-3 first-line trials, the CMS3 NanoString subtype was present in 2% of samples (CALGB 80405) compared with 12% of CMS3 microarray subtype (FIRE-3) [5, 6]. Therefore, the proportion of CMS3 identified with different assays in these cohorts requires further understanding. As previously mentioned, no definitive conclusions related to the role of the subtypes in predicting benefit from bevacizumab or cetuximab can be drawn from these two similar studies. While significant survival benefit was demonstrated in the CMS1-bevacizumab group and in the CMS2-cetuximab group in the CALGB 80405, no significant differences in the CMS1 group was shown and the survival benefit associated with cetuximab seemed mainly driven by the CMS4 group in the FIRE-3 [5, 6]. Given the previously discussed inter-platform consistency and the fact that the same algorithm was used to predict the subtypes, the differences in number and sets of genes analyzed may be a major contributor to inconsistent results.

Despite the potential clinical utility of CRCSC signatures for outcome prediction or immune-targeted therapy development, their clinical implementation is challenging due to lack of easy-to-use and cost-effective assays suitable for paraffin tissues. As previously indicated, different groups, including ours, are working on classifiers based on protein markers by immunohistochemistry or gene expression signals using nCounter® NanoString Technologies, for example, with overall accuracy close to 90% when compared with the gold-standard CMS4 signature [32–35]. Technical validation has been proved for our NanoString-based classifier, and clinical validation studies are underway [32, 33]. In parallel, prospective molecularly stratified clinical trials should be encouraged. One example is the MoTriColor H2020 project, where mCRC patients with tumors testing positive for a ‘TGF-β active’ or ‘MSI-like’ gene expression signature in archived paraffin tissue are eligible to the combination of galunisertib (TGF-β receptor inhibitor) and capecitabine or the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, respectively [36].

Conclusions and future directions

Molecular subtypes are context specific. The CMS subtypes identify a further level of heterogeneity beyond standard genomic biomarkers in CRC. To maximize their potential for personalized medicine, the contexts of application and equivocal factors must be extensively considered to avoid misleading results and premature rejection of a highly informative classification system.

Acknowledgements

RMH/ICR authors acknowledge NHS funding for National Institute for Health Research Royal Marsden and Institute of Cancer Research Biomedical Research Centre. AS acknowledges Cancer Research UK for PhD funding for EF through the ICR/RMH.

Funding

None declared.

Disclosure

AS has ownership interest as a patent inventor for a patent entitled ‘Colorectal cancer classification with differential prognosis and personalized therapeutic responses’ (patent number PCT/IB2013/060416). AS—Research Funding—Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA and Pierre Fabre. RS - Advisory boards: Amgen, VCN-BCN, Agendia, Guardant Health, Roche, Ferrer, Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen, Merck, Lilly, MSD; Speaker: Amgen, Pfizer, Novartis, Merck, MSD, AZD, Celgene, Sace Medhealth; Consulting company: Sace Medhealth. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012; 487(7407): 330.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R. et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(8): 1386–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM. et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colon cancer, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16(4): 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X. et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21(11): 1350.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lenz HJ, Ou FS, Venook AP. et al. Impact of consensus molecular subtyping (CMS) on overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). JCO 2017; 35(Suppl 15): 3511–3511. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stintzing S, Wirapati P, Lenz HJ. et al. Consensus molecular subgroups (CMS) of colorectal cancer (CRC) and first-line efficacy of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab in the FIRE3 (AIO KRK-0306) trial. JCO 2017; 35(Suppl 15): 3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mooi JK, Wirapati P, Asher R. et al. The prognostic impact of consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) and its predictive effects for bevacizumab benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: molecular analysis of the AGITG MAX clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(11): 2240–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marisa L, Ayadi M, Balogoun R. et al. Clinical utility of colon cancer molecular subtypes: validation of two main colorectal molecular classifications on the PETACC-8 phase III trial cohort. JCO 2017; 35(Suppl 15): 3509. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadanandam A, Lyssiotis CA, Homicsko K. et al. A colorectal cancer classification system that associates cellular phenotype and responses to therapy. Nat Med 2013; 19(5): 619.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medico E, Russo M, Picco G. et al. The molecular landscape of colorectal cancer cell lines unveils clinically actionable kinase targets. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 7002.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Del Rio M, Mollevi C, Bibeau F. et al. Molecular subtypes of metastatic colorectal cancer are associated with patient response to irinotecan-based therapies. Eur J Cancer 2017; 76: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maringe C, Walters S, Rachet B. et al. Stage at diagnosis and colorectal cancer survival in six high-income countries: a population-based study of patients diagnosed during 2000–2007. Acta Oncol 2013; 52(5): 919–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fontana E, Poudel P, Nyamundanda G. et al. 108PCharacterisation of heterogeneity in microsatellite instable (MSI) tumours associated with distinct cell types and immune phenotypes. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(Suppl 5): mdx363.024. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khambata-Ford S, Garrett CR, Meropol NJ. et al. Expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin and K-ras mutation status predict disease control in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. JCO 2007; 25(22): 3230–3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J. et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2011; 117(20): 4623–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hugen N, Van de Velde CJ, De Wilt JH, Nagtegaal ID.. Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(3): 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Østrup O, Dagenborg VJ, Rødland EA. et al. Molecular signatures reflecting microenvironmental metabolism and chemotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death in colorectal liver metastases. Oncotarget 2017; 8(44): 76290.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robinson MW, Harmon C, O’Farrelly C.. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol 2016; 13(3): 267.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunne PD, McArt DG, Bradley CA. et al. Challenging the cancer molecular stratification dogma: intratumoral heterogeneity undermines consensus molecular subtypes and potential diagnostic value in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(16): 4095–4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alderdice M, Richman SD, Gollins S. et al. Prospective patient stratification into robust cancer cell intrinsic subtypes from colorectal cancer biopsies. J Pathol 2018; 245(1): 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Cutsem E, Labianca R, Bodoky G. et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. JCO 2009; 27(19): 3117–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teufel M, Schwenke S, Seidel H. et al. Molecular subtypes and outcomes in regorafenib-treated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) enrolled in the CORRECT trial.

- 23. Eide PW, Bruun J, Lothe RA, Sveen A.. CMScaller: an R package for consensus molecular subtyping of colorectal cancer pre-clinical models. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1): 16618.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okita A, Takahashi S, Ouchi K. et al. Consensus molecular subtypes classification of colorectal cancer as a predictive factor for chemotherapeutic efficacy against metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2018; 9(27): 18698.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marisa L, de Reyniès A, Duval A. et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med 2013; 10(5): e1001453.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fontana E, Nyamundanda G, Cunningham D. et al. Molecular subtype assay to reveal anti-EGFR response sub-clones in colorectal cancer (CRC). JCO 2018; 36(Suppl 4): 658–658. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song N, Pogue-Geile KL, Gavin PG. et al. Clinical outcome from oxaliplatin treatment in stage II/III colon cancer according to intrinsic subtypes: secondary analysis of NSABP C-07/NRG oncology randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(9): 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Laurent-Puig P, Marisa L, Ayadi M. et al. Le Malicot K, Lepage C, Emile JF, Salazar R, Aust D. 60PD Colon cancer molecular subtype intratumoral heterogeneity and its prognostic impact: an extensive molecular analysis of the PETACC-8. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(Suppl 8): mdy269.058. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen X, Deane NG, Lewis KB. et al. Comparison of nanostring nCounter® data on FFPE colon cancer samples and affymetrix microarray data on matched frozen tissues. PLoS One 2016; 11(5): e0153784.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richard AC, Lyons PA, Peters JE. et al. Comparison of gene expression microarray data with count-based RNA measurements informs microarray interpretation. BMC Genomics 2014; 15(1): 649.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prokopec SD, Watson JD, Waggott DM. et al. Systematic evaluation of medium-throughput mRNA abundance platforms. RNA 2013; 19(1): 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ragulan C, Eason K, Nyamundanda G. et al. A low-cost multiplex biomarker assay stratifies colorectal cancer patient samples into clinically-relevant subtypes. bioRxiv 2017; 1: 174847. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fontana E, Ragulan C, Eason K. et al. 145O Validated nCounter platform to stratify colorectal cancer (CRC) into Consensus Molecular Subtypes (CMS) and CRCassigner subtypes in Asian population. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(Suppl 10): mdx659.003. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Trinh A, Trumpi K, Sousa EMF D. et al. Practical and robust identification of molecular subtypes in colorectal cancer by immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(2): 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fontana E, Ragulan C, Cunningham D. et al. Multiplatform assay to classify formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) colorectal cancer (CRC) samples into molecular subtypes with mutational profiles. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(Suppl 5): mdx393.097. [Google Scholar]

- 36. http://www.motricolor.eu/ (31 May 2018, date last accessed)