Sir,

We present a very rare case of squamous cell lung cancer having spontaneous regression (St. Peregrine tumor) with a synchronous primary renal cancer.

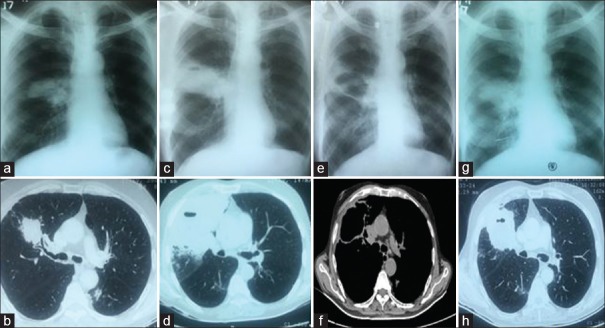

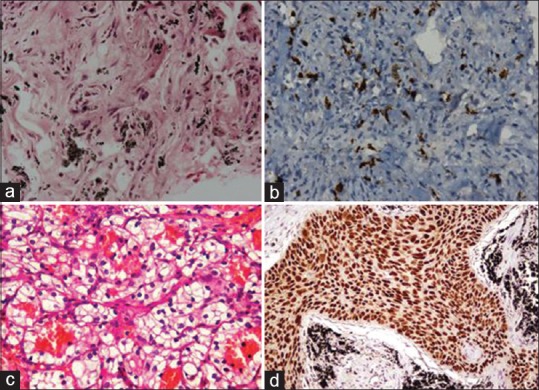

A 74-year-old male, chronic smoker with smoking index of more than 20 pack year, Stage III chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, presented with worsening exertional dyspnea and productive cough of 2-month duration. His chest radiograph showed a right parahilar opacity [Figure 1a]. The high-resolution computed tomography (CT) of chest showed a solid lesion in the right upper lobe with spiculated margin, internal hypoenhancing area, and positive bronchus sign [Figure 1b]. An incidental note was also made of a heterogeneously enhancing lesion in the mid pole of the right kidney. The sputum examination was negative for acid-fast bacilli, pyogenic culture, and GeneXpert. A fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) was performed. The TBLB was inconclusive. A CT-guided lung biopsy was performed. The chest radiograph and CT scan performed at the time of CT-guided biopsy showed that the lesion had significantly increased in size [Figure 1c and d]. It showed mixed inflammatory infiltrate, pigmented macrophages, and dense bronchoalveolar and interstitial fibrosis. The immunohistochemistry of the specimen was positive for CD8+ cells and natural killer cell, but there was no evidence of pyogenic infection or tuberculosis. A repeat biopsy was planned. However, the patient was lost to follow-up and reported back after 1 month. The chest radiograph and CT scan showed that the lesion became cystic [Figure 1e and f]. Hence, ultrasound-guided needle aspiration from the right kidney was done, which came positive for malignant cells. The patient underwent nephrectomy. Histopathological examination of the kidney mass revealed clear-cell carcinoma. The follow-up chest radiograph and CT after nephrectomy [Figure 1g and h] showed increase in size again. CT-guided lung biopsy now showed squamous cell carcinoma of lung, positive for P63 and P40 and negative for transcription termination factor 1. The first lung biopsy, immunohistochemistry, kidney biopsy, and second lung biopsy are shown in Figure 2a–d. The final diagnosis made was – spontaneously regressing squamous cell carcinoma lung – “St. Peregrine tumor” – with “synchronous primary” clear-cell carcinoma right kidney.

Figure 1.

(a) Chest radiograph at presentation to us showing increase in the size of the right hilar region compared to previous radiograph shown in . (b) Chest computed tomography scan lung window, transverse cut at the level of carina, corresponding to the chest radiograph in a showing mass with tumor bronchus sign. (c) Chest radiograph after 1 month of a showing further increase in the size of the right hilar lesion. (d) Chest computed tomography scan lung window transverse cut at the level of carina, at the time of first computed tomography-guided biopsy corresponding with radiograph of c showing mass in the right upper lobe extending up to the pleura. (e) Chest radiograph after 1 month of c showing a cystic opacity at the site where initially solid lesion was seen. (f) Corresponding computed tomography scan to the chest radiograph shown in e, mediastinal window at the level of carina showing cystic opacity and regression of lesion. (g) Chest radiograph almost 3 months after nephrectomy showing re appearance of the lesion at the same site. (h) Corresponding computed tomography scan to the chest radiograph in g, lung window at the level of carina showing solid mass in right upper lobe

Figure 2.

(a) The first histopathology sample which showed infiltration of lung parenchyma by inflammatory cells. (b) ×40 view of immunohistochemistry of first biopsy positive for CD8 cells. (c) ×40 view of histopathology of kidney mass showing clear cell carcinoma. (d) ×40 view of histopathology of second biopsy from lung mass with hematoxylin and eosin staining showing squamous cell carcinoma

Everson and Cole defined spontaneous regression (SR) as the partial or complete disappearance of a malignant tumor.[1] Kumar et al.[2] presented “modified Everson and Cole criterion” which defines SR as: (1) the partial or complete disappearance of the tumor in the absence of all systemic or local treatment of the primary or metastatic lesion, (2) the patient has not received any systemic therapy (chemotherapy, radio-ablative techniques, and chemoembolization), and (3) primary malignancy is histologically diagnosed or the lesion appears malignant radiographically or clinically. This phenomenon of SR is known for several hundred years and is also termed as St. Peregrine tumor.[1] In our patient, the lesion had almost completely disappeared, he did not receive any specific treatment, the lesion appeared malignant radiologically, and it was proven malignant subsequently. Since he satisfied all the criteria, he was diagnosed to have “St. Peregrine tumor.”

The incidence of SR is reported to be 1 in 60,000–100,000.[3] Kumar et al.[2] reported only two cases of SR due to primary lung cancers from 71 cases between 1951 and 2008. We could find only nine cases of squamous cell carcinoma having SR in MeSH database of PubMed. In majority of the reported cases, the possible cause of SR was not known [Table 1].[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]

Table 1.

Various case reports of spontaneous regression of squamous cell carcinoma lung

| Authors | Histologic type | Smoking status | TNM stage | Involvement of other organ | Possible cause of SR | Year of publication | Place of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sperduto et al.[4] | Squamous cell | Yes | T1N2M1 | Adrenals | Not specified | 1988 | England |

| Liang et al.[5] | Squamous cell | N/A | T2N2M0 | None | Herbs | 2004 | China |

| Pujol et al.[6] | Squamous cell | Yes | N/A | Brain | Anti Hu Ab | 2007 | France |

| Gladwish et al.[7] | Squamous cell | Yes | T2N3M0 | Breast carcinoma | Herbal remedy Essiac | 2010 | Canada |

| Furukawa et al.[8] | Squamous cell | Yes | T1N0M0 | None | Not specified | 2011 | Japan |

| Choi et al.[9] | Squamous cell | N/A | N/A | None | Immune system alteration secondary to infection (TB) | 2013 | South Korea |

| Park et al.[10] | Squamous cell | N/A | T4N2M1 | Breast metastasis | Korean ginseng | 2016 | South Korea |

| Esplin et al.[11] | Squamous cell | Yes | T1N0M0 | None | Not specified | 2018 | USA |

| Ariza-Prota et al.[12] | Squamous cell | Yes | T3N3M1 | Skin | Not specified | 2018 | Spain |

N/A: Not available, TB: Tuberculosis, SR: Spontaneous regression, TNM: Tumor-nodes-metastasis

The possible mechanisms that are associated with SR are apoptosis, immune mediated, microenvironment changes, and DNA oncogenic suppression.[13] Coley had proposed a role of infection in regression of tumors.[14] Studies conducted by Scheider et al. and Iwakami et al. showed regulatory T-cells and CD8-positive lymphocytes, respectively, in lung malignancies with SR.[15] The biopsy specimen of our patient showed CD8+ cells and natural killer cell, suggesting that T-cell-mediated reaction around the tumor leads to regression. The immunological reaction leading to SR in our case was possibly due to synchronous primary because lung cancer regressed in the presence of renal cancer and the removal of renal cancer led to reappearance of lung cancer. The presence of two malignancies in our patient, i.e., multiple primary malignancies, were synchronous primary tumors because they were diagnosed within a 6-month interval.

To conclude, there have been case reports of synchronous primary lung and renal cancer, but squamous cell carcinoma of lung and clear cell carcinoma of kidney have not been reported so far. The synchronous primary possibly led to immunological regression of lung cancer.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the department of pathology for providing us the histopathology photomicrographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Everson TC, Cole WH. Spontaneous regression of malignant disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1959;169:1758–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.03000320060014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar T, Patel N, Talwar A. Spontaneous regression of thoracic malignancies. Respir Med. 2010;104:1543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperduto P, Vaezy A, Bridgman A, Wilkie L. Spontaneous regression of squamous cell lung carcinoma with adrenal metastasis. Chest. 1988;94:887–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang HL, Xue CC, Li CG. Regression of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung by Chinese herbal medicine: A case with an 8-year follow-up. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pujol JL, Godard AL, Jacot W, Labauge P. Spontaneous complete remission of a non-small cell lung cancer associated with anti-Hu antibody syndrome. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:168–70. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e31802f1c9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladwish A, Clarke K, Bezjak A. Spontaneous regression in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2010. 2010:pii: bcr0720103147. doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2010.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furukawa M, Oto T, Yamane M, Toyooka S, Kiura K, Miyoshi S, et al. Spontaneous regression of primary lung cancer arising from an emphysematous bulla. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:577–9. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.10.01638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SM, Go H, Chung DH, Yim JJ. Spontaneous regression of squamous cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e5–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1417IM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park YH, Park BM, Park SY, Choi JW, Kim SY, Kim JO, et al. Spontaneous regression in advanced squamous cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:E235–9. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.02.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esplin N, Fergiani K, Legare TB, Stelzer JW, Bhatti H, Ali SK, et al. Spontaneous regression of a primary squamous cell lung cancer following biopsy: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:65. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1589-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariza-Prota M, Martínez C, Casan P. Spontaneous regression of metastatic squamous cell lung cancer. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:995–8. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salman T. Spontaneous tumor regression. J Oncol Sci. 2016;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jessy T. Immunity over inability: The spontaneous regression of cancer. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:43–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Pastorini A, Plönes T, Brockmann M, Ludwig C, Beckers F, Stoelben E, et al. Spontaneous regression of non-small cell lung cancer after biopsy of a mediastinal lymph node metastasis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:217. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0702-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]