Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of sentence length on intelligibility and measures of speech motor performance in persons with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and to determine how these effects were influenced by dysarthria severity levels.

Method

One hundred thirty-one persons with ALS were included in this study, stratified into 4 dysarthria severity groups. All participants produced sentences from 5 to 15 words in length. Intelligibility, speaking rate, and measures of speech pausing behavior (i.e., total speech duration, total pause duration, and mean speech event duration) were measured for each sentence. Linear mixed-effects models were used to determine the effect of sentence length on speech measures for speakers at different dysarthria severity levels.

Results

Results showed that speech intelligibility significantly declined at longer sentence lengths only for the speakers with ALS who had more advanced dysarthria symptoms; however, speakers with mild-to-severe dysarthria showed significant declines in speaking rate and speech pausing behavior at longer sentence lengths.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that producing shorter sentences may help maximize intelligibility for speakers with moderate-to-severe dysarthria secondary to ALS and may be a beneficial compensatory strategy for preserving motor effort for all speakers with dysarthria secondary to ALS.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive motor neuron disease that causes deterioration of motor function, including declines in motor speech function and eventual loss of intelligible speech. Progression of motor speech impairment in ALS typically begins with a reduction in speaking rate followed by a rapid decline in intelligibility (Ball, Beukelman, & Pattee, 2002; Ball, Willis, Beukelman, & Pattee, 2001), which substantially affects functional communication. Although most people with ALS will eventually require augmentative and alternative communication support, targeted speech strategies, such as rate reduction, hyperarticulation, and prosodic manipulations (Hanson, Yorkston, & Britton, 2011; Yorkston, Beukelman, & Ball, 2002), have the potential to significantly prolong the ability to use verbal communication. Because of the progressive course of ALS, compensatory speech strategies can help maximize intelligibility and communication efficiency, while minimizing fatigue (Hanson et al., 2011).

One potentially simple and impactful compensatory strategy is controlling the length of spoken utterances. Utterance length is known to have a significant effect on speech intelligibility in persons with motor speech disorders (Allison & Hustad, 2014; Hustad, 2007) as well as other populations (Howell, Au-Yeung, & Pilgrim, 1999; Sitler, Schiavetti, & Metz, 1983). Within the same speaker, longer units of connected speech, including sentences and narratives, tend to be more intelligible than words produced in isolation because sentences provide a rich source of linguistic context that enhance a listener's ability to recover degraded speech (Carter, Yorkston, Strand, & Hammen, 1996; Hammen, Yorkston, & Dowden, 1991; Hustad, 2007). Compared to single words, sentences provide linguistic context (i.e., syntactic structure and semantic cues), which may allow listeners to accurately infer words that would otherwise be unintelligible. From this perspective, using short utterances may limit intelligibility for speakers with motor speech impairments and suggests that these individuals with dysarthria should be encouraged to produce multiword utterances, regardless of etiology. On the other hand, the motoric demands of speaking increase in longer units of connected speech. Prior studies have shown that increasing utterance length taxes the speech motor systems of even older adults without neurological disorders, including inducing increased lung volumes and reductions in speaking rate for longer versus shorter sentences (Huber, 2008). These findings raise the possibility that in persons with dysarthria, speech intelligibility may decline in longer utterances, as the motor demands of producing the utterance exceed the capabilities of a compromised speech motor system.

This trade-off between increased linguistic context and increased motor load may have different effects on intelligibility depending on the severity of a speaker's dysarthria. Prior research has shown that the discrepancy in intelligibility between single-words and sentences is greatest for mildly degraded speech and becomes smaller as speech becomes more degraded (Miller, Heise, & Lichten, 1951). Studies of speakers with severe-to-profound dysarthria have yielded mixed results that may be speaker specific. Sentence intelligibility in these speakers can be either higher, equivalent (Dongilli, 1994; Yorkston & Beukelman, 1978), or lower (Yorkston & Beukelman, 1981) than that of single words. This study focused on this trade-off between linguistic context and speech motor demands by examining the effect of sentence length on speech intelligibility for speakers with ALS at a range of dysarthria severity levels. We hypothesized that speakers with moderate-to-severe dysarthria would be more negatively affected by the increased motor load of long sentences and demonstrate relatively less benefit from the increased linguistic context compared to speakers with mild or no dysarthria symptoms.

To better understand the impact of sentence length on speech motor load in persons with dysarthria due to ALS, we also examined the effect of sentence length on measures of speech motor performance. Specifically, we focused on speaking rate, which includes both periods of continuous speech and pauses, as well as its component speech and pause behaviors: articulation rate (i.e., rate of speech excluding pauses) and pausing within sentences. In healthy speakers, increased sentence length has been shown to elicit faster speaking rates because speakers tend to shorten the duration of individual speech sounds in longer sentences, thus increasing their articulation rates (Fónagy & Magdics, 1960; Lehiste, 1972). Healthy speakers also pause more as utterance length increases, but pause locations and durations are driven by multiple factors, including the syntactic and semantic structures of the utterance as well as the physiological need to breathe, and speakers flexibly adjust their pausing patterns in accordance with the utterance characteristics (Grosjean & Collins, 1979; Hammen & Yorkston, 1994). In persons with ALS, however, reduced speaking and articulatory rates and increased pausing are robust indicators of the presence and severity of speech motor impairment (Yunusova et al., 2016).

Speaking rate is a common diagnostic measure used to track speech decline in ALS because it is affected prior to speech intelligibility and it declines linearly with disease progression (Ball et al., 2001; Ball et al., 2002). Both slowing of articulatory movements and increases in the frequency and duration of pauses in an utterance can contribute to slowed speaking rate. For speakers with dysarthria, breath placement in utterances tends to be primarily determined by the physiological need to breathe (Grosjean & Collins, 1979; Hammen & Yorkston, 1994), which can lead to grammatically inappropriate pauses in longer utterances that affect speech intelligibility (Hammen & Yorkston, 1996; Liss, Spitzer, & Lansford, 2009). Over the course of ALS, the number of words produced between breaths becomes progressively fewer as respiratory reserve decreases and articulatory fatigue progresses (Yunusova et al., 2016; Yunusova, Weismer, Kent, & Rusche, 2005), and increased pausing in connected speech can be among the first signs of detectable change in speech motor performance for persons with ALS (Allison et al., 2017; Rong, Yunusova, Wang, & Green, 2015). Given its sensitivity to speech motor impairment in ALS, speech pausing behavior may also provide a robust index of how speech motor load changes with increased utterance length. We hypothesized that speakers with moderate-to-severe dysarthria may have similar speech pausing behavior to speakers with mild or no dysarthria in short utterances, but as utterance length increases, their speech pausing behavior may become more atypical (i.e., more frequent or longer pauses; shorter durations of continuous speech intervals between pauses).

Collectively, evidence suggests that utterance length may be an important factor to consider in planning speech treatment and optimizing efficacy of compensatory speech strategies for people with ALS; however, previous research has not examined how dysarthria severity influences utterance length effects for a large group of speakers with this diagnosis. Understanding how utterance length influences intelligibility and speech motor performance for individuals who vary in dysarthria severity is important for setting severity-specific treatment goals and may provide valuable information for maximizing efficacy of speech intervention.

This study aimed to determine the effect of increased sentence length on intelligibility, speaking rate, and speech pausing behavior and to determine whether dysarthria severity influences these effects. The following specific research questions were addressed.

Does sentence length affect intelligibility for speakers with ALS, and does the effect differ depending on dysarthria severity?

Does sentence length affect speaking rate for speakers with ALS, and does the effect differ depending on dysarthria severity?

Does sentence length affect speech and pausing behavior within a sentence (i.e., articulation rate and pause duration) for speakers with ALS, and does the effect differ depending on dysarthria severity?

Method

Participants

One hundred thirty-one people with ALS participated in this study (52 F, 79 M). All participants had been diagnosed with ALS by a neurologist based on the El Escorial criteria (Brooks, Miller, Swash, & Munsat, 2000) and were enrolled in a longitudinal study of speech and swallowing decline in ALS. Participants additionally met the following inclusion criteria: (a) spoke English as their primary language, (b) had no prior history of neurological disorders, and (c) had hearing within normal limits and adequate vision and literacy skills to read stimuli. For this study, only data from each participant's last visit were included because participants were generally enrolled in the longitudinal study in early disease stages, and for this study, we were interested in capturing the range of severity (including data from people later in disease progression). The average age of participants in the sample was 60.3 years (SD = 10.1 years).

We used a communication staging model for ALS developed by Yorkston and colleagues as a guide for stratifying participants into severity subgroups (K. Yorkston & Beukelman, 1999). This model separates speakers with ALS into four communication stages: in Communication Stage (CS) 1, speakers with ALS have no detectable speech impairment; in CS2, speech impairment is detectable, and rate slowing can decrease efficiency of communication, but intelligibility is preserved; in CS3, intelligibility begins to decline; and in CS4, persons with ALS become reliant on augmentative and alternative communication for functional communication. To classify participants for this study, we operationally defined each of these stages using intelligibility and speaking rate cut scores based on the participants' performance on the Speech Intelligibility Test (SIT; procedures described below) (Yorkston, Beukelman, Hakel, & Dorsey, 2007). Cut scores for speaking rate were based on prior literature showing that for persons with ALS, intelligibility tends to decline rapidly once rate slows below 125 words per minute (WPM) (Ball et al., 2001; Ball et al., 2002). Intelligibility cut scores for dysarthria severity levels are not well established in the literature, but for this study, a cut score of 90% was chosen to ensure that speakers included in CS3 had clear reduction in intelligibility. Participants were classified as CS1 if they had intelligibility over 90% and speaking rate over 125 WPM. Participants were classified as CS2 if they had intelligibility below 90% and speaking rate below 125 WPM. Participants were classified as CS3 if they had intelligibility between 45% and 90% and as CS4 if they had intelligibility below 45%. The number of participants classified into each communication stage group was as follows: CS1, n = 72; CS2, n = 20; CS3, n = 28; CS4, n = 11. The demographic characteristics of these groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in each communication stage group.

| Communication stage | n | Mean age (SD) | Gender |

Onset (Bulbar/Spinal/Generalized) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | Bulbar | Spinal | Gen. | Unknown | |||

| CS1 | 72 | 59.7 (10) | 25 | 47 | 2 | 56 | 5 | 9 |

| CS2 | 20 | 60 (8) | 1 | 10 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 3 |

| CS3 | 28 | 61.8 (12) | 9 | 19 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 3 |

| CS4 | 11 | 61 (8) | 8 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Intelligibility and Speaking Rate

The SIT was administered to all participants. The SIT is a commonly used and well-researched measure of intelligibility and is an established measure for tracking speech decline in ALS (Ball et al., 2002; Ball, Beukelman, & Patee, 2004; Hanson, Yorkston, & Britton, 2011). In addition, the SIT was designed to be used by presenting speakers with sentences of increasing length and, thus, is an appropriate measure for addressing our research questions. The current version of this software selects 11 sentences, ranging in length from 5 to 15 words in length, for participants to read aloud. Each participant produced a different set of sentences, which were randomly selected by the SIT software from a corpus of 1,100 sentences. Each participant was recorded while producing one sentence of each length (5-word, 6-word, 7-word,…, 15-word). All participants read sentences in order of increasing length. Audio recordings at each study site were collected in a quiet data collection room, using a head-mounted microphone positioned approximately 4 in. from the participant's mouth.

Intelligibility of the SIT was scored following the SIT instruction manual (Yorkston et al., 2007). The sentences produced by each speaker were orthographically transcribed from audio recordings by a research assistant who was unfamiliar with the participants. Sentence productions were peak-amplitude normalized before being transcribed to eliminate any influence of volume differences on intelligibility measurements. Each participant's sentence productions were transcribed by one listener; however, across the set of 131 participants, several research assistants completed the transcriptions. Because the SIT recordings were collected over the course of several years as part of a multisite study, multiple research assistants were involved in SIT transcription. All research assistants were trained to transcribe the SIT sentences with the same set of instructions and only allowed to listen to each sentence two times. None of the research assistants were certified speech-language pathologists or expert listeners. The SIT software was used to calculate the percent intelligibility for each sentence (sentence intelligibility = # words correctly identified in sentence/# words in sentence × 100), as well as the speaker's overall intelligibility (overall intelligibility = # total words correctly identified across all sentences/total words produced × 100). The duration of each sentence was measured using Adobe Audition. Rate was calculated within the SIT software by dividing the number of words produced by the total sentence duration in minutes to yield a rate for each sentence in words per minute. This measure included within-sentence pauses. For each speaker, an overall speaking rate was determined by averaging the speaking rates for each sentence. Although intelligibility transcriptions were only completed by one judge for this study, recent research from our lab has demonstrated strong intrajudge reliability for intelligibility (r = .92) and speaking rate (r = .92) measurements from the SIT (Stipancic, Yunusova, Berry, & Green, 2018). Overall intelligibility and overall speaking rate were used to determine communication stage groupings as defined above.

Speech Pause Analysis

A subset of participants was selected for analysis of speech pausing behavior during sentence production. Because the SIT scores were obtained a decade earlier as part of a large multicenter study on bulbar motor decline, audio recordings were not retained for all participants. Therefore, participants for the pause analysis were selected from the full sample based on the availability of audio recordings. The primary groups of interest were CS2 and CS3, who are most likely to benefit from speech strategies. Five speakers from CS2 and seven speakers from CS3 were omitted from this analysis, due to lack of clear audio recordings. Since the CS1 group was overrepresented in the full sample, we randomly selected a smaller set of participants from this group to make the group size comparable to other communication stage groups. CS4 was excluded from this analysis, due to lack of a sufficient number of recordings. The number of participants in this sample was as follows: CS1, n = 27; CS2, n = 15; CS3, n = 21.

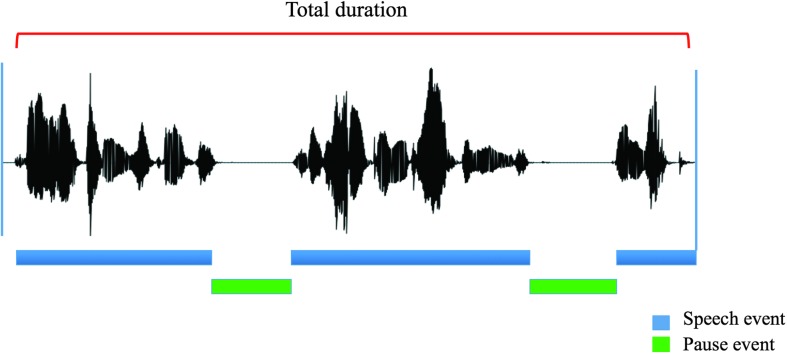

Speech pause analysis (SPA), a MATLAB software program (Green, Beukelman, & Ball, 2004), was used to analyze the speech and pausing behaviors of the participants' sentence productions from the SIT. Each sentence produced on the SIT was segmented into an individual sound file. SPA uses sound-level and duration thresholds to automatically detect pauses in recorded speech samples. For the current analysis, pauses were defined as silent intervals over 250 ms in duration, consistent with previous literature (Green et al., 2004; Rosen et al., 2010). The sound-level threshold used was 25 dB. Figure 1 provides an illustration of SPA and how the variables of interest were measured.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating variables measured using the automated speech pause analysis (SPA). The maximum amplitude of a selected pause region is used to establish a threshold for separating “speech” from “pause” events. Amplitude values above this threshold mark boundaries for speech events; values below this threshold mark boundaries for speech events. Pause and speech event durations below 250 and 25 ms, respectively, were not included in the analysis. For each Speech Intelligibility Test sentence, three primary variables were extracted from SPA: (a) total speech duration = summed duration of speech events in a sentence, (b) total pause duration = summed duration of pause events in a sentence, and (c) mean speech event duration = average duration of speech events in a sentence.

There were three primary variables of interest that were considered from SPA for this study: total speech duration, total pause duration, and mean speech event duration. All measures were automatically calculated by the SPA software and defined as follows: Total speech duration was defined as the summed duration of speech events (excluding pauses) in each sentence. In this study, we considered this measure as a proxy for articulation rate because sentences were controlled for the number of words; hence, the total speech duration would be expected to reflect just the portion of the sentence involving articulatory movement. Total pause duration was defined as the summed duration of pause events within each sentence. Although total speech duration and total pause duration are expected to increase with increased sentence length in words, the relative rates of increase between severity groups were expected to provide information about how the motor demands of increased sentence length differentially affect speakers with ALS in different communication stage groups. Mean speech event duration was defined as the average duration of the speech events, which were uninterrupted runs of continuously produced speech. Although SPA measurements are generated automatically by the software, manual input is required to identify a nonspeech region within each sample prior to analysis. Therefore, we calculated interjudge reliability on the SPA measurements for 10 participants' SIT sentence recordings. The 10 participants were randomly selected from each severity group (four from CS1, three from CS2, three from CS3). Comparison of the first and second sets of measurements showed 100% exact agreement on all SPA measures for the 10 participants.

Statistical Analysis

Linear mixed-effects (LME) models were conducted using R (R Core Team, 2017) and the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) to determine the effect of sentence length on intelligibility, speaking rate, and within-sentence pausing behavior. LME models are advantageous for repeated measures designs because they can account for individual variability. Subjects were included as random intercepts to account for individual variability in speech motor skills and sentence characteristics (e.g., word frequency, predictability, number of syllables). Sets of LME models were conducted for each of the five outcome variables of interest: intelligibility, speaking rate, total speech duration, total pause duration, and average speech event duration. For each set of models, sentence length and communication stage were included as fixed effects. Sentence length was centered in the models to facilitate interpretability of findings, so intercepts reflect the value of the outcome variable in 10-word sentences. CS1 was used as the reference group in all models. Modeling started by including only communication stage and subject as factors, and subsequent models added sentence length and an interaction term to determine whether adding these factors improved model fit. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare successively more complex models. To determine the most parsimonious model that best fits the data, factors were added to the model until including an additional factor no longer significantly improved model fit (Singer & Willett, 2003). Pairwise differences between slopes were obtained using the lsmeans package in R (Lenth, 2016), which uses Tukey's method to compare groups (p values are corrected for multiple comparisons).

Results

Effect of Sentence Length on Intelligibility

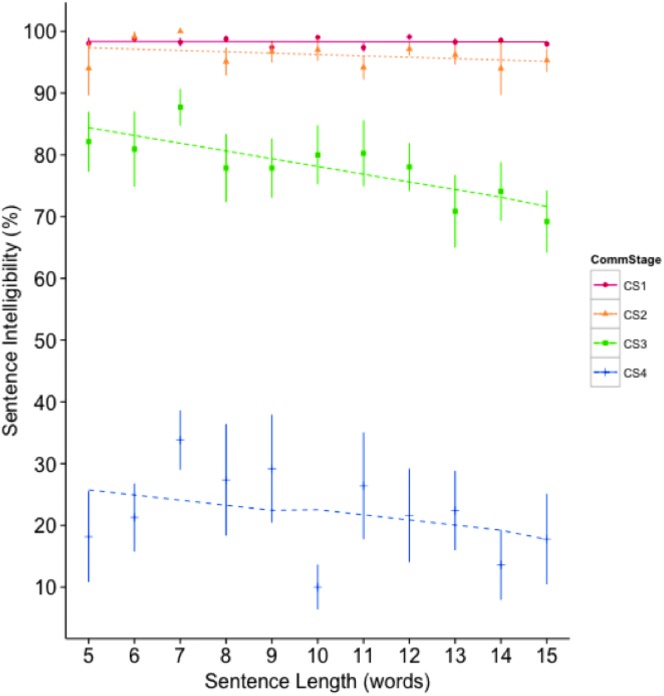

The mean intelligibility scores for each communication stage group at each sentence length are shown in Figure 2. Descriptively, data show a decline in intelligibility as sentence length increases for speakers in the CS3 and CS4 groups, but minimal change in intelligibility across sentence lengths for groups CS1 and CS2. The first set of LME models was conducted to examine the effects of sentence length and communication stage on intelligibility. The best-fitting model contained sentence length, communication stage, and their interaction as fixed effects. Results of this model, presented in Table 2, indicated that increased sentence length did not have a significant effect on intelligibility for speakers in CS1; however, sentence length had a significantly more negative effect on intelligibility for speakers in the CS3 and CS4 groups compared to CS1. There was no significant difference in the effect of sentence length on intelligibility between CS2 and CS1.

Figure 2.

Sentence intelligibility as a function of sentence length.

Table 2.

Results of linear mixed-effects models estimating the effect of sentence length and communication stage on sentence intelligibility, speaking rate, total speech duration, and total pause duration.

| Variable | Intelligibility |

Speaking rate |

Total speech duration |

Total pause duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | t | Estimate (SE) | t | Estimate (SE) | t | Estimate (SE) | t | |

| (Intercept) | 98.32(0.95) | 103.08*** | 176.85 (3.68) | 48.03*** | 3.32 (0.18) | 18.17*** | 0.28 (0.15) | 1.87 |

| Sentence Length | −0.01 (0.15) | −0.05 | −0.71 (0.26) | −2.76** | 0.30 (0.01) | 21.28*** | 0.07 (0.01) | 4.67*** |

| CS2 | −2.08 (2.04) | −1.02 | −71.12 (7.90) | −9.01*** | 1.71 (0.31) | 5.58*** | 1.04 (0.25) | 4.18*** |

| CS3 | −20.21 (1.80) | −11.20*** | −60.02 (6.96) | −8.62*** | 1.47 (0.28) | 5.32*** | 1.06 (0.23) | 4.69*** |

| CS4 | −76.72 (2.65) | −28.99*** | −103.23 (10.15) | −10.17*** | --------- | --------- | --------- | --------- |

| SentLength*CS2 | −0.21 (0.31) | −0.68 | --------- | --------- | 0.19 (0.02) | 7.92*** | 0.16 (0.02) | 6.86*** |

| SentLength*CS3 | −1.25 (0.28) | −4.50*** | --------- | --------- | 0.11 (0.02) | 4.96*** | 0.18 (0.02) | 8.25*** |

| SentLength*CS4 | −0.82 (0.42) | −1.97 | --------- | --------- | --------- | --------- | --------- | --------- |

Note. CS = communication stage. Dashes indicate “not applicable.”

p < .01.

p < .001.

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to compare slopes between the four communication stage groups. Results showed that speakers in CS3 had a significantly different slope than the CS1 (p < .0001) and CS2 (p = .02) groups, indicating that sentence length had a significantly greater effect on intelligibility for speakers in CS3 than for those in CS1 and CS2. The slope of CS4 did not significantly differ from any other group.

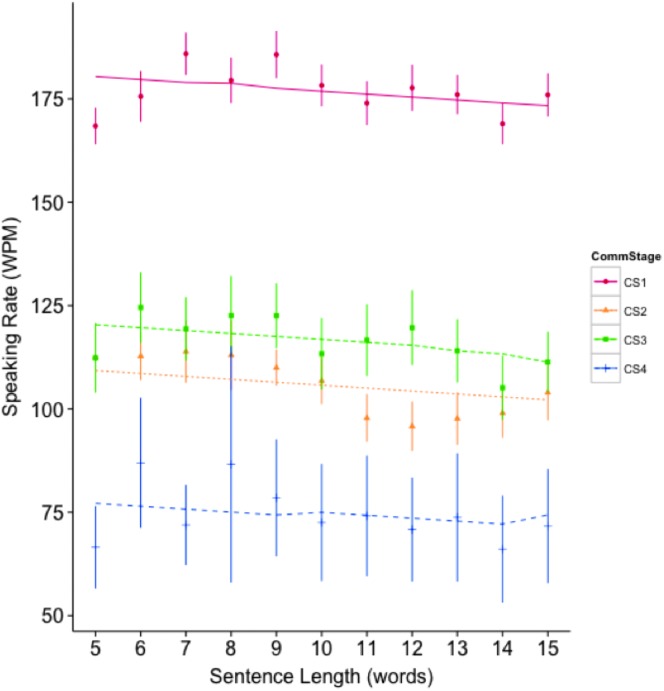

Effect of Sentence Length on Speaking Rate

Mean speaking rates for each communication stage group at each sentence length are shown in Figure 3. Descriptively, data show a decline in speaking rate as sentence length increased, which is similar across communication stage groups. A second set of LME models was conducted to examine the effects of sentence length and communication stage on speaking rate. The best-fitting model in this analysis contained sentence length and communication stage as fixed effects in predicting speaking rate. Adding an interaction term between sentence length and communication stage did not significantly improve model fit. Results of the best-fitting model are shown in Table 2. Results indicated that speaking rate significantly declined with increased sentence length, regardless of the communication stage.

Figure 3.

Speaking rate (in words per minute [WPM]) as a function of sentence length.

Effect of Sentence Length on SPA Measures

To examine the relations between sentence length and speech pausing behavior, acoustic speech pausing data from the reduced subset of participants were analyzed using LME models to test the effect of sentence length and communication stage on the three outcome variables of interest: total speech duration (i.e., the summed duration of speech events in a sentence), total pause duration (i.e., the summed duration of pause events in a sentence), and mean speech event duration (i.e., the average duration of a speech event within a sentence). Figures showing the effect of sentence length and communication stage group on each of these variables are shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6, respectively.

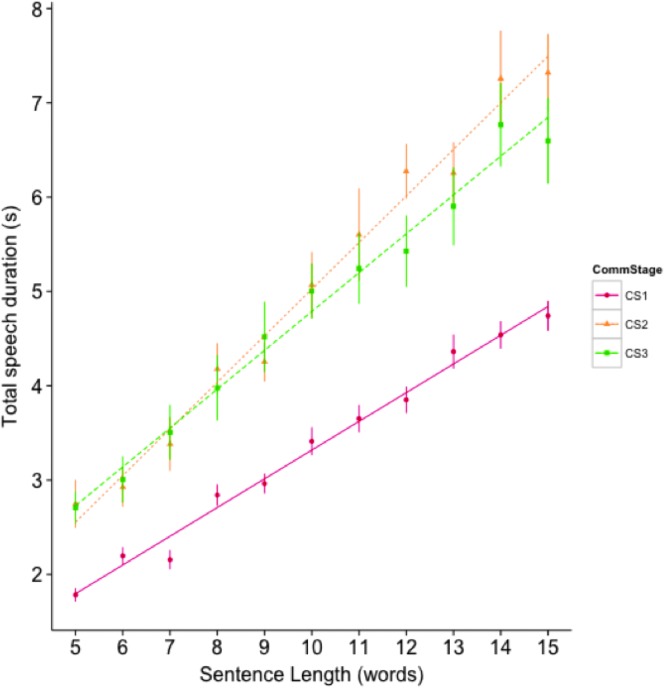

Figure 4.

Total speech duration (pauses removed) (in seconds [s]) as a function of sentence length.

Figure 5.

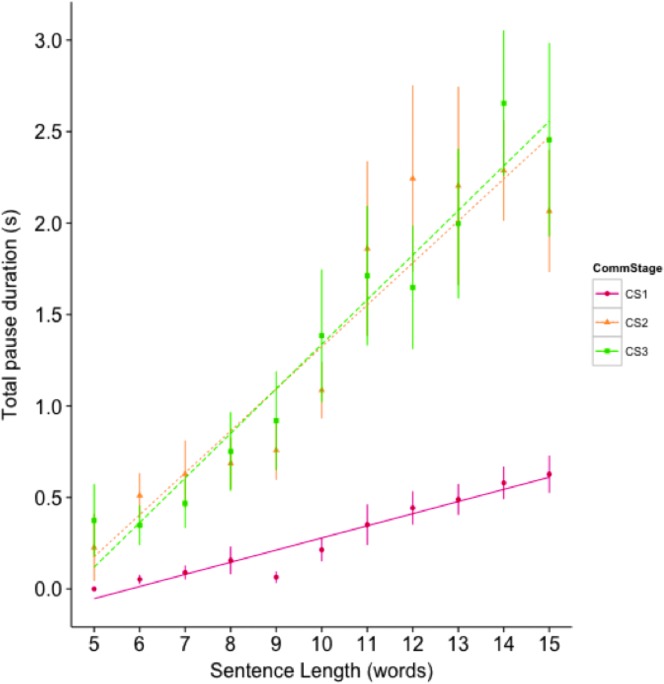

Total pause duration (in seconds [s]) as a function of sentence length.

Figure 6.

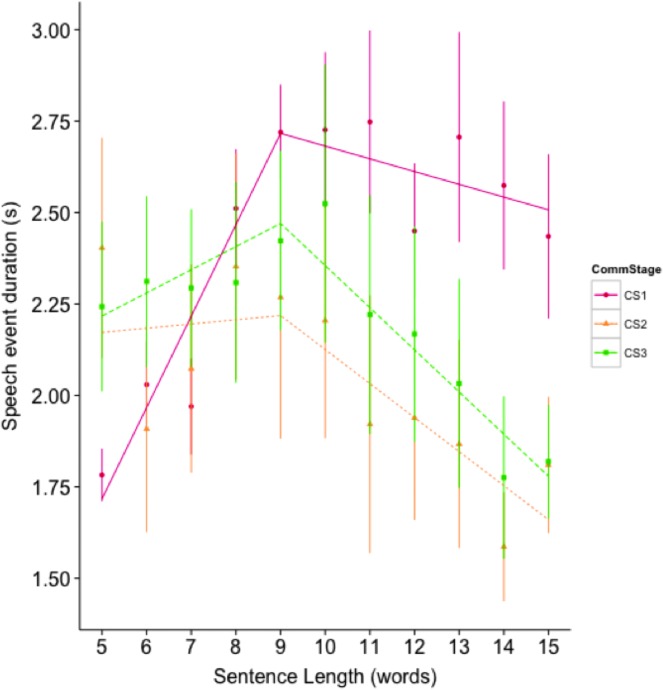

Mean speech event duration (in seconds [s]) as a function of sentence length.

Total Speech Duration and Total Pause Duration

As expected, total speech duration and total pause duration showed a positive linear increase as sentence length increased for all three communication stage groups. LME models indicated that models containing sentence length, communication stage, and an interaction between sentence length and communication stage provided the best model fit for predicting both total speech duration and total pause duration. Results of the best-fitting models for both measures are shown in Table 2.

Results indicated that the effect of sentence length on total speech duration was significantly greater for the CS2 and CS3 groups compared to CS1. There was also a significant effect of communication stage on total speech duration, with speakers in CS2 and CS3 having significantly longer total speech durations in 10-word sentences than speakers in the CS1 group. Results of pairwise comparisons showed significant differences in slope between all three groups, indicating that speakers in CS2 had a significantly faster rate of increase in speech duration as sentence length increased compared to CS3 (p < .01) and CS1 (p < .0001) and that speakers in CS3 had a significantly faster rate of increase in speech duration as sentence length increased compared to CS1 (p < .0001).

In addition, results indicated that the effect of sentence length on total pause duration was significantly greater for the CS2 and CS3 groups compared to CS1. There was also an effect of communication stage on total pause duration, with speakers in CS2 and CS3 having significantly longer total pause durations in 10-word sentences than speakers in the CS1 group. Results of pairwise comparisons indicated that speakers in CS3 and CS2 had significantly faster rates of increase in pause duration as sentence length increased compared to speakers in CS1 (p < .0001 for both comparisons), but there was no significant difference between slopes of the CS2 and CS3 groups.

Mean Speech Event Duration

Mean speech event duration did not show a linear relationship with sentence length. As seen in Figure 6, mean speech event durations appeared to increase with sentence length until sentences were about nine words in length, and then decreased. Therefore, we used a breakpoint LME model (Singer & Willett, 2003) to estimate the effect of sentence length on mean speech event duration in short sentences (i.e., sentences 5–9 words in length) and long sentences (i.e., sentences 9–15 words in length). The best-fitting model included short-sentence length, long-sentence length, communication stage, and Short-Sentence Length × Communication Stage and Long-Sentence Length × Communication Stage interactions. Results of this model are shown in Table 3. Results indicated that in short sentences, sentence length was significantly related to mean speech event duration in CS1, and this effect was significantly greater for CS1 than for CS2 and CS3. In long sentences, there was no significant effect of sentence length on mean speech event duration for CS1 and no significant difference in slopes between CS1 and CS2 or CS3. Results of pairwise comparisons indicated that in short sentences, speakers in the CS1 group showed a significantly faster increase in mean speech event duration as sentence length increased than speakers in groups CS2 (p = .01) and CS3 (p = .03), but slopes of CS2 and CS3 did not significantly differ from each other. No significant group differences in slope were found in long sentences.

Table 3.

Results of the linear mixed-effects model best estimating the effect of sentence length and communication stage on mean speech event duration.

| Variable | Estimate (SE) | t |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.72 (0.21) | 13.01*** |

| Sent_short | 0.25 (0.05) | 5.13*** |

| Sent_long | −0.03 (0.03) | −1.14 |

| CS2 | −0.50 (0.35) | −1.43 |

| CS3 | −0.25 (0.32) | −0.78 |

| Sent_short*CS2 | −0.24 (0.08) | −2.92** |

| Sent_short*CS3 | −0.19 (0.07) | −2.53* |

| Sent_long*CS2 | −0.06 (0.05) | −1.14 |

| Sent_long*CS3 | −0.08 (0.05) | −1.74 |

Note. Sent = sentence; CS = communication stage.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Compensatory speech strategies can help maximize intelligibility and communication efficiency, while minimizing fatigue for speakers with dysarthria secondary to ALS (Hanson et al., 2011; Hanson, Yorkston, & Beukelman, 2004). Controlling the length of spoken utterances is a potentially simple compensatory strategy that has been understudied. This study aimed to determine the effect of sentence length on intelligibility and speech motor performance for people with ALS at different dysarthria severity levels. There were two primary findings: (a) shorter sentences maximized intelligibility in speakers with advanced dysarthria and (b) longer sentences had a detrimental impact on speech motor performance for speakers with dysarthria of any severity level. These findings have several significant implications for improving the assessment and management of speech impairment in persons with dysarthria due to ALS.

Short Sentences Maximized Intelligibility in Persons With Advanced Dysarthria

In this study, we hypothesized that for long sentences, there would be a trade-off between the intelligibility enhancing effects of increased linguistic context and the intelligibility degrading effects of increased motor load, particularly for speakers with more severe speech motor impairment. Results did not demonstrate a benefit of increased sentence length to intelligibility for any group of speakers with ALS; on the contrary, increased sentence length had a detrimental effect on intelligibility for persons with advanced dysarthria. Specifically, speakers with ALS who had mild or no dysarthria symptoms (i.e., those in CS1 and CS2) did not show a significant change in intelligibility with increased sentence length. This finding is due to a ceiling effect; speakers in these groups were approximately 100% intelligible at all sentence lengths. In contrast, speakers with more severe dysarthria showed a clear, significant decline in intelligibility as sentence length increased. For speakers in CS3, for whom dysarthria was severe enough to affect overall intelligibility, sentence intelligibility was approximately 13% higher in 5-word sentences than in 15-word sentences. Prior work suggests that a change in intelligibility of approximately 12% on the SIT is clinically meaningful (Stipancic et al., 2018). Speakers with severe-to-profound dysarthria (i.e., those in CS4) also showed a similar but not statistically significant decline in intelligibility with increased sentence length. Speakers in the CS3 group are optimal candidates for behavioral speech intervention because they have reduced intelligibility, but still primarily rely on verbal communication. Therefore, this finding suggests a potential benefit of controlling utterance length as a compensatory strategy for speakers in this group, by itself or in conjunction with other speech strategies.

Previous research has shown mixed findings regarding the relations between utterance length and intelligibility for people with advanced dysarthria, across various dysarthria types and etiologies (e.g., anoxia, traumatic head injury, cerebral palsy [CP]) (Hustad, 2007; Yorkston & Beukelman, 1978, 1981). Results of this study suggest that for speakers with ALS who have moderate-to-severe dysarthria, there is a benefit to intelligibility of producing shorter sentences compared to longer sentences. One possible explanation for this finding is that the detrimental effect of increased motor load imposed by longer sentences may have outweighed any benefit of increased linguistic context for speakers in this group. Similar explanations have been evoked to explain why increased sentence length has a more detrimental effect on intelligibility for children with dysarthria secondary to CP compared to children with CP who do not have dysarthria (Allison & Hustad, 2014). Compared to other populations of speakers with dysarthria, persons with ALS may be particularly vulnerable to increased motor demands because the disease results in muscle weakness and fatigue (Mitsumoto, 1997). Prior work demonstrating the benefit of increased linguistic context for intelligibility in adults with dysarthria has largely focused on comparisons between single-word intelligibility and sentence intelligibility (Yorkston & Beukelman, 1978, 1981), rather than comparing sentences of increasing length. Thus, it is also possible that the increased linguistic context provided by 15-word sentences compared to 5-word sentences was not sufficient to have a notable effect on intelligibility.

Why Longer Sentences Had a Detrimental Effect on Speech Motor Performance for Speakers With Dysarthria

Degeneration of the upper and lower motor neurons causes declines in muscle strength for people with ALS and results in the need for increased effort to perform motor tasks like speech or swallowing (Plowman, 2015). This loss of functional reserve capacity makes people with ALS more vulnerable to difficulty performing tasks with high motor load (Green et al., 2013; Plowman, 2015). Declines in speech motor performance with increased task demands can be one indication of decreased functional reserve. In this study, declines in speech motor performance were evident in the participants with dysarthria, regardless of whether or not dysarthria was severe enough to affect intelligibility, which may reflect decreased functional reserve for speech. Specifically, all speakers with dysarthria showed greater rates of increase in speech duration and pause duration, and decreased flexibility in mean speech event duration as sentence length increased, relative to the speakers without dysarthria symptoms.

Analysis of speech and pausing behaviors in a subset of participants indicated that as sentence length increased, both groups of speakers with dysarthria (i.e., CS2 and CS3) increased their total speech duration (excluding pauses) and total pause duration significantly more than speakers without dysarthria (i.e., CS1). Their relatively greater increase in total speech duration with longer sentence length suggests that speakers with dysarthria were slowing their articulation rate as sentence length increased, compared to the speakers without dysarthria. Similarly, their greater increase in total pause duration suggests that speakers with dysarthria were pausing relatively more as sentence length increased, compared to the speakers without dysarthria. Both of these findings can be interpreted as signs of declining efficiency of speech motor performance with increased sentence length. The steeper rates of change in speech and pause durations could also reflect fatigue in the speakers with dysarthria because all participants produced sentences in order of increasing length from 5 to 15 words. Although our study did not include a group of neurologically healthy speakers, prior work has shown that healthy adult speakers increase their articulation rate as utterance length increases (Fónagy & Magdics, 1960; Lehiste, 1972). This contrasts with the current results from the speakers with dysarthria and further supports the hypothesis that the speakers with dysarthria showed declining speech motor performance with increased sentence length.

Speech event duration data further indicated that increased sentence length taxed the speech motor systems of speakers with dysarthria more than those without dysarthria. In short sentences, speakers without dysarthria showed a significant increase in speech event duration between five- and nine-word sentences because they were generally able to produce these sentences on one breath, and adapted their speech event durations accordingly. In contrast, speakers with dysarthria showed little change in speech event duration between five- and nine-word sentences. This finding suggests that speakers with dysarthria had decreased flexibility in modulating their speech event durations to accommodate increasing sentence length compared to the speakers without dysarthria symptoms, further suggesting decreased functional motor reserve for speech. Our earlier research suggested that this measure (i.e., speech event duration) was associated with the decline in the functional respiratory reserve primarily due to the progression of respiratory deficit in ALS (Yunusova et al., 2016). Previous research has demonstrated that physiological breath needs modulate breath placement more for speakers with dysarthria than for those without dysarthria (Grosjean & Collins, 1979; Hammen & Yorkston, 1994), which may underlie this reduced flexibility in adjusting speech event duration.

Declines in Speech Motor Performance Can Be Clinically Meaningful for All Speakers With Dysarthria

Collectively, findings from the analysis of speech pausing behaviors suggest that all of the speakers with dysarthria showed declines in speech motor performance at longer sentence lengths, suggesting decreased functional motor reserve, even if their intelligibility was not yet affected. Because speaking requires submaximal levels of muscle strength (Kent, 2015), it is likely that some degree of functional reserve can be lost in speech musculature before intelligibility is affected, but prior research has also shown that these early declines in functional reserve may be measurable in high-demand speech tasks. Previous studies have shown that tasks with high motoric load, such as passage reading (a prolonged speech task) and diadochokinesis (a quasi-speech task that taxes speed of movement and respiratory capacity), are able to reveal declines in speech motor performance prior to clinically observable changes in speech intelligibility (Allison et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2015). Declines in efficiency of speech motor performance at longer utterance lengths can be clinically meaningful, even for those who are not yet experiencing intelligibility declines, because further slowing of already slowed speech for speakers with dysarthria can pose additional challenges for listeners (Weismer, Laures, Jeng, Kent, & Kent, 2000; Yorkston, Hammen, Beukelman, & Traynor, 1990) and have negative consequences on communication participation (Ball et al., 2004). In addition, this decreased efficiency may indicate that long sentences are fatiguing the speech motor system for these speakers, which can be contraindicated in ALS (Tomik & Guiloff, 2010).

Clinical Implications

Findings from this study have important therapeutic implications, as they suggest that speakers with reduced intelligibility secondary to ALS might benefit from using length control as a strategy to maximize intelligibility. Although breath group strategies are often used by clinicians and have been shown to be effective in a few case studies (Bellaire, Yorkston, & Beukelman, 1986; Moore & Scudder, 1989), the therapeutic benefit of using shorter sentences has not been studied explicitly in persons with ALS. Future research should investigate the added benefit to speech intelligibility of combining sentence length control with other compensatory speech strategies. Current findings also suggest that teaching speakers with even mild dysarthria to control utterance length and use shorter sentences may be beneficial for preserving energy and maximizing communication efficiency. Future research is needed to examine the efficacy of this strategy alone and in conjunction with other compensatory speech techniques.

Results of this study also have potential implications for motor speech assessment in persons with ALS. Prior research has shown that speech tasks with higher motor demands, such as paragraph reading and diadochokinesis, can reveal presymptomatic declines in quantitative measures of motor speech function in speakers with ALS (Allison et al., 2017; Green et al., 2013; Rong et al., 2015). Current findings suggest that for speakers with mild dysarthria, using longer sentences in assessment may be more likely to reveal subtle speech motor deficits than using shorter sentences. Additional research is needed to examine how motor speech performance changes in other speech dimensions, such as articulatory kinematics and acoustic distinctiveness, with increased sentence length in people with ALS at different severity levels.

Limitations and Future Directions

Results of this study demonstrate that sentence length affects intelligibility and speech motor performance for persons with dysarthria secondary to ALS and supports the need for future research on the potential benefits of controlling sentence length as a compensatory speech strategy. Although the results are promising, there are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The sentence stimuli used in this study were from a well-established intelligibility test; however, speakers only produced one sentence of each length and sentences differed across speakers. In addition, speakers may modulate their rate and speech pausing behaviors in connected speech differently than in read sentences; future work is needed to examine how modifying sentence length in spontaneous speech affects intelligibility and speech motor performance of speakers with ALS at different dysarthria severity levels. Also, this study used a combination of overall intelligibility and overall speaking rate to group speakers into communication stage groups, and examined intelligibility and speaking rate at the sentence level as outcome variables. Using an independent measure to define severity groupings would strengthen future studies; however, our group stratification method did not affect our ability to statistically examine continuous relations between sentence length and sentence-level speech outcome measures. Furthermore, respiratory status needs to be controlled for in the future studies of rate and pausing behaviors as the respiratory decline may affect these measures independently or in combination with the bulbar motor (oropharyngeal) deficits.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that for individuals with moderate-to-severe dysarthria secondary to ALS, the increased motor demands of producing longer sentences are detrimental to intelligibility and are not offset by the boost from additional linguistic context. In addition, longer sentences were associated with a decrease in communication efficiency due to both an increase in pausing and slowing of articulation for speakers with dysarthria of all severity levels. Together, these findings suggest the potential importance of considering sentence length in the assessment and treatment of dysarthria associated with ALS and motivate the need for future research in this area.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants R01DC009890 and R01DC0135470 (awarded to Jordan Green) and Grant K24DC016312 (awarded to Yana Yunusova) and the ALS Society of Canada Denise Ramsay Discovery Grant and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Planning Grant FRN126682 (awarded to Yana Yunusova). The authors would like to thank Brian Richburg for his assistance with this project, as well as the participants and their families who made this work possible.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants R01DC009890 and R01DC0135470 (awarded to Jordan Green) and Grant K24DC016312 (awarded to Yana Yunusova) and the ALS Society of Canada Denise Ramsay Discovery Grant and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Planning Grant FRN126682 (awarded to Yana Yunusova).

References

- Allison K. M., & Hustad K. C. (2014). Impact of sentence length and phonetic complexity on intelligibility in 5 year old children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(4), 396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison K. M., Yunusova Y., Campbell T. F., Wang J., Berry J. D., & Green J. R. (2017). The diagnostic utility of patient-report and speech-language pathologists' ratings for detecting the early onset of bulbar symptoms due to ALS. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, 18(5–6), 358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. J., Beukelman D. R., & Pattee G. L. (2002). Timing of speech deterioration in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 10(4), 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. J., Beukelman D. R., & Pattee G. L. (2004). Communication effectiveness of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37(3), 197–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. J., Willis A., Beukelman D. R., & Pattee G. (2001). A protocol for identification of early bulbar signs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 191(1–2), 43–53.11676991 [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B., & Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bellaire K., Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. R. (1986). Modification of breath patterning to increase naturalness of a mildly dysarthric speaker. Journal of Communication Disorders, 19(4), 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B. R., Miller R. G., Swash M., & Munsat T. L. (2000). El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 1(5), 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. R., Yorkston K. M., Strand E. A., & Hammen V. L. (1996). Effects of semantic and syntactic context on actual and estimated sentence intelligibility of dysarthric speakers. In Disorders of motor speech: Assessment, treatment and clinical characterization (pp. 67–87). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Dongilli P. (1994). Semantic context and speech intelligibility. In Motor speech disorders: Advances in assessment and treatment (pp. 175–191). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Fónagy I., & Magdics K. (1960). Speed of utterance in phrases of different lengths. Language and Speech, 3(4), 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Green J. R., Beukelman D. R., & Ball L. J. (2004). Algorithmic estimation of pauses in extended speech samples of dysarthric and typical speech. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 12(4), 149–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. R., Yunusova Y., Kuruvilla M. S., Wang J., Pattee G. L., Synhorst L., … Berry J. D. (2013). Bulbar and speech motor assessment in ALS: Challenges and future directions. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration, 14(7–8), 494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean F., & Collins M. (1979). Breathing, pausing and reading. Phonetica, 36(2), 98–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen V. L., & Yorkston K. M. (1994). Respiratory patterning and variability in dysarthric speech. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 2(4), 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen V. L., & Yorkston K. M. (1996). Speech and pause characteristics following speech rate reduction in hypokinetic dysarthria. Journal of Communication Disorders, 29(6), 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen V. L., Yorkston K. M., & Dowden P. (1991). Index of contextual intelligibility: Impact of semantic context in dysarthria. In Moore C., Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. (Eds.), Dysarthria and apraxia of speech: Perspectives on management (pp. 43–53). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson E. K., Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. R. (2004). Speech supplementation techniques for dysarthria: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 12(2), ix–xxix. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson E. K., Yorkston K. M., & Britton D. (2011). Dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review of characteristics, speech treatment and augmentative and alternative communication options. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 19(3), 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Howell P., Au-Yeung J., & Pilgrim L. (1999). Utterance rate and linguistic properties as determinants of lexical dysfluencies in children who stutter. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 105(1), 481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber J. E. (2008). Effects of utterance length and vocal loudness on speech breathing in older adults. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 164(3), 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad K. C. (2007). Effects of speech stimuli and dysarthria severity on intelligibility scores and listener confidence ratings for speakers with cerebral palsy. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 59(6), 306–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent R. D. (2015). Nonspeech oral movements and oral motor disorders: A narrative review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24, 763–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehiste I. (1972). The timing of utterances and linguistic boundaries. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 51(6B), 2018–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R. V. (2016). Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software, 69(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liss J. M., Spitzer S. M., & Lansford K. L. (2009). The differential effects of dysarthria type on lexical segmentation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 125(4), 2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. A., Heise G. A., & Lichten W. (1951). The intelligibility of speech as a function of the context of the test materials. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 41(5), 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumoto H. (1997). Diagnosis and progression of ALS. Neurology, 48(4, Suppl. 4), 2S–8S. [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. A., & Scudder R. R. (1989). Coordination of jaw muscle activity in Parkinsonian movement: Description and response to traditional treatment. In Yorkston K. M. & Beukelman D. R. (Eds.), Recent advances in clinical dysarthria (pp. 147–164). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Plowman E. K. (2015). Is There a role for exercise in the management of bulbar dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(4), 1151–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

- Rong P., Yunusova Y., Wang J., & Green J. R. (2015). Predicting early bulbar decline in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A speech subsystem approach. Behavioural Neurology, 2015, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen K., Murdoch B., Folker J., Vogel A., Cahill L., Delatycki M., & Corben L. (2010). Automatic method of pause measurement for normal and dysarthric speech. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(2), 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J. D., & Willett J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Chicago, IL: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sitler R. W., Schiavetti N., & Metz D. E. (1983). Contextual effects in the measurement of hearing-impaired speakers' intelligibility. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 26(1), 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipancic K. L., Yunusova Y., Berry J. D., & Green J. R. (2018). Minimally detectable change and minimal clinically important difference of a decline in sentence intelligibility and speaking rate for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61, 2757–2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomik B., & Guiloff R. J. (2010). Dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 11(1–2), 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismer G., Laures J. S., Jeng J. Y., Kent R. D., & Kent J. F. (2000). Effect of speaking rate manipulations on acoustic and perceptual aspects of the dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 52(5), 201–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. (1999). Staging interventions in progressive dysarthria. SIG 2 Perspectives on Neurophysiology and Neurogenic Speech and Language Disorders, 9(4), 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. R. (1978). A comparison of techniques for measuring intelligibility of dysarthric speech. Journal of Communication Disorders, 11, 499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., & Beukelman D. R. (1981). Communication efficiency of dysarthric speakers as measured by sentence intelligibility and speaking rate. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46(3), 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., Beukelman D. R., & Ball L. J. (2002). Management of dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Geriatrics and Aging, 5, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., Beukelman D. R., Hakel M., & Dorsey M. (2007). Speech intelligibility test for Windows. Lincoln, NE: Communication Disorders Software. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K. M., Hammen V. L., Beukelman D. R., & Traynor C. D. (1990). The effect of rate control on speech rate and intelligibility of dysarthric speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55, 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunusova Y., Graham N. L., Shellikeri S., Phuong K., Kulkarni M., Rochon E., … Green J. R. (2016). Profiling speech and pausing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). PloS One, 11(1), e0147573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunusova Y., Weismer G., Kent R. D., & Rusche N. M. (2005). Breath-group intelligibility in dysarthria: characteristics and underlying correlates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(6), 1294–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]