Abstract

Differences in health status by socioeconomic position (SEP) tend to be more evident at older ages, suggesting the involvement of a biological mechanism responsive to the accumulation of deleterious exposures across the lifespan. DNA methylation (DNAm) has been proposed as a biomarker of biological aging that conserves memory of endogenous and exogenous stress during life.

We examined the association of education level, as an indicator of SEP, and lifestyle-related variables with four biomarkers of age-dependent DNAm dysregulation: the total number of stochastic epigenetic mutations (SEMs) and three epigenetic clocks (Horvath, Hannum and Levine), in 18 cohorts spanning 12 countries.

The four biological aging biomarkers were associated with education and different sets of risk factors independently, and the magnitude of the effects differed depending on the biomarker and the predictor. On average, the effect of low education on epigenetic aging was comparable with those of other lifestyle-related risk factors (obesity, alcohol intake), with the exception of smoking, which had a significantly stronger effect.

Our study shows that low education is an independent predictor of accelerated biological (epigenetic) aging and that epigenetic clocks appear to be good candidates for disentangling the biological pathways underlying social inequalities in healthy aging and longevity.

Keywords: socioeconomic position, education, biological aging, epigenetic clocks

Introduction

Aging is characterized by a gradual and constant increase in health inequalities across socioeconomic groups [1,2], an association based on strong epidemiological evidence known as the ‘social gradient in health’. On average, individuals with lower socioeconomic position (SEP) have lower life expectancy, higher risk of age-related diseases, and poorer quality of life at older ages compared with less disadvantaged groups. Although lifestyles differ by SEP, unhealthy habits only partially explain this association [3].

The role of epigenetic mechanisms in response to trauma, and evidence for their involvement in intergenerational transmission of biological impacts of traumatic stress have been proposed to explain how social adversity gets biologically embedded [4], leading to differences in biological functionalities among individuals in different social conditions, especially at older ages. Epigenetics, specifically DNA methylation (DNAm) has been proposed as one of the most powerful biomarkers of biological aging and as one of the plausible biological mechanisms by which social adversities get ‘under the skin’ and affect physiological and cellular pathways leading to disease susceptibility [5–7].

Two different mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to age-related DNAm changes: ‘epigenetic drift’ and the ‘epigenetic clock’ that sometimes are used as synonyms even though describe different molecular mechanisms [8–10]. Although both are related to aging, epigenetic drift represents the trend of increasing DNAm variability over time across the whole genome. On the contrary, the epigenetic clock refers to specific CpG sites identified in specific DNA regions at which DNAm levels constantly increase (or decrease depending on the site) during aging and can be used to predict chronological age with high accuracy [11]. Two measures of epigenetic clocks have gained considerable popularity, Horvath [11] and Hannum [12], and the concept of epigenetic aging acceleration (EAA) has been introduced as the difference between predicted DNAm age and chronological age. EAA has been associated with all-cause mortality, cancer incidence and neurodegenerative disorders, as well as non-communicable disease risk factors such as obesity, poor physical activity, unhealthy diet, cumulative lifetime stress and infections [13,14]. Recently, Levine and colleagues introduced a ‘next-generation epigenetic clock’ that is based on a set of CpGs associated with a complex set of clinical measures thought to assess the ‘phenotypic age’ [15]. Levine EAA was found to outperform other measures with regard to the prediction of a variety of aging outcomes, including all-cause mortality, the incidence of and survival from cancer, and physical functioning [15].

In contrast to EAA, epigenetic drift is a mechanism that involves the whole-genome, where age-related genomic instability and chromatin deterioration lead to increased variability of genome-wide DNAm levels at older ages [16]. Different statistical approaches can be used to evaluate the impact of epigenetic drift on aging and disease susceptibility. For example, Teschendorff and colleagues suggested that methods based on differential DNAm variability could identify risk markers more robustly than statistical measures based on differences in mean DNAm levels [17]. Gentilini and colleagues developed an analytical approach to identify these stochastic epimutations (SEMs) [18] from genome-wide DNAm data, showing that the number of SEMs increases exponentially with age although there is high variability within individuals of the same age. A higher number of SEMs was found to be associated with X chromosome inactivation skewing in women (an age-related condition and risk factor for cancer), hepatocellular carcinoma tumor staging [18,19], and unhealthy exposure such as cigarette smoking, alcohol intake [20] and exposure to toxicants [21], suggesting SEMs as possible biomarkers of exposure-related accumulation of DNA damage during lifespan.

Given the above, it can be assumed that the various epigenetic clocks (Horvath’s, Hannum’s, Levine’s) and the total number of SEMs describe different aspects of the biological (epigenetic) aging process. We previously showed a dose-response relationship between SEP and EAA. Further, our results suggest that the effect could be partially reversible by improving social conditions during life [5]. In addition, ours and two more recent studies indicate that childhood SEP might have a stronger effect on EAA than adulthood SEP [22,23].

Despite extensive research in the field, to date no studies have compared the effect of SEP on epigenetic aging biomarkers with those of other lifestyle-related risk factors for age-related diseases. We aimed to systematically investigate the association of education level, as a proxy for SEP, with the total number of SEMs and ‘accelerated aging’ as assessed using the three epigenetic clocks, and to compare the independent effect of low education with those of the main modifiable risk factors for premature aging: smoking, obesity, alcohol intake and physical inactivity, by conducting a meta-analysis including data for more than 16,000 individuals belonging to 18 cohort studies from 12 different countries worldwide.

RESULTS

After quality control and sample filtering, we analyzed blood DNAm data from 16,245 individuals from 18 cohort studies. The main characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. For each epigenetic outcome, we report the results of a meta-analysis of the association with education, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake and physical activity in Table 2. Model 1 includes age, sex, and cohort-specific covariates as adjustment variables whereas Model 2 is the fully adjusted model (additionally adjusted for smoking, BMI, alcohol intake and physical activity).

Table 1. Study sample descriptive statistics.

| Cohort short name | Cohort full name | Country | Illumina BeadChip | N | Mean age (min - max) | Female N(%) | Reference |

| AIRWAVE | The Airwave Health Monitoring Study | UK | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 1,127 | 41 (13 - 65) | 458 (41%) | [46] |

| EXPOsOMICS 'EPIC CVD' | The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition - EXPOsOMICS subsample | Italy | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 313 | 57 (35 - 75) | 167 (53%) | [47] |

| EPIC | The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition | Italy | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 1,803 | 53 (35 - 75) | 1,114 (62%) | [48] |

| ESTHER 1 | Epidemiological investigations on chances of preventing, recognizing early and optimally treating chronic diseases in an elderly population | Germany | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 1,000 | 62 (48 - 75) | 500 (50%) | [49] |

| ESTHER 2 | Epidemiological investigations on chances of preventing, recognizing early and optimally treating chronic diseases in an elderly population | Germany | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 864 | 63 (48 - 75) | 390 (45%) | [49] |

| KORA | Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA-F4) | Germany | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 1,727 | 61 (32 - 81) | 882 (51%) | [50] |

| MCCS | Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study | Australia | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 2,817 | 59 (40 - 70) | 1,095 (39%) | [51] |

| NAS | Normative aging study | USA | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 624 | 72 (55 - 91) | 0 (0%) | [52] |

| NOWAC | The Norwegian Women and Cancer Study | Norway | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 632 | 56 (47 - 63) | 632 (100%) | |

| NICOLA | Northern Ireland Cohort Longitudinal Study of Ageing | Northern Ireland | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 1,929 | 64 (40 - 96) | 988 (51%) | [53] |

| RS-Bios | Rotterdam Study 1,2 | Netherlands | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 720 | 68 (52 - 80) | 304 (42%) | [54] |

| RSIII-1 | Rotterdam Study 3 | Netherlands | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 730 | 60 (46 - 89) | 335 (46%) | [54] |

| SAPALDIA | Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults | Switzerland | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 402 | 57 (38 - 81) | 184 (46%) | [REMOVED HYPERLINK FIELD] [55] |

| SKIPOGH a | Swiss Kidney Project on Genes in Hypertension | Switzerland | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 250 | 51 (26 - 82) | 132 (53%) | [56] |

| SKIPOGH b | Swiss Kidney Project on Genes in Hypertension | Switzerland | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 451 | 54 (25 - 89) | 231 (51%) | [56] |

| TERRE | Case-control study of Parkinson’s disease in French farmers (only controls were used) | France | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 174 | 67 (41 - 76) | 80 (46%) | [57] |

| TILDA | The Irish Longitudinal Study on aging | Ireland | Illumina EPIC chip (850K) | 490 | 62 (50 - 80) | 246 (50%) | [58] |

| YFS | Young Finns Study | Finland | Illumina 450K BeadChip | 186 | 44 (34 - 49) | 72 (39%) | [59] |

Table 2. Results of linear regressions using epigenetic aging biomarkers as outcomes and lifestyle related risk factors as predictors.

| SEMs | HorvathEAA | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Education (ref: High) | Medium | 0.23 (0.02; 0.44)* | 0.17 (-0.07; 0.42) | 0.11 (-0.07; 0.28) | 0.11 (-0.08; 0.29) |

| Low | 0.34 (0.11; 0.58)** | 0.28 (0.04; 0.51)* | 0.22 (0.03; 0.41)* | 0.19 (0.00; 0.39)+ | |

| Smoking (ref: Never) | Former | 0.32 (0.14; 0.49)*** | 0.33 (0.16; 0.51)*** | 0.13 (-0.04; 0.29) | 0.11 (-0.05; 0.26) |

| Current | 0.53 (0.32; 0.73)*** | 0.51 (0.30; 0.72)*** | -0.06 (-0.24; 0.13) | -0.08 (-0.27; 0.12) | |

| Obesity (ref: BMI < 25) | BMI < 30 | -0.01 (-0.18; 0.16) | -0.01 (-0.18; 0.15) | 0.37 (0.22; 0.52)*** | 0.33 (0.18; 0.48)*** |

| BMI ≥ 30 | -0.06 (-0.26; 0.15) | -0.07 (-0.27; 0.14) | 0.45 (0.27; 0.63)*** | 0.43 (0.24; 0.61)*** | |

| Alcohol (ref: Abstainer) | Occasional | -0.12 (-0.31; 0.08) | -0.10 (-0.29; 0.08) | -0.02 (-0.19; 0.15) | 0.00 (-0.18; 0.18) |

| Habitual | 0.22 (-0.05; 0.49) | 0.15 (-0.11; 0.4) | 0.19 (-0.07; 0.44) | 0.25 (0.00; 0.49)* | |

| Physical activity (ref: High) | Medium | 0.00 (-0.21; 0.21) | -0.03 (-0.21; 0.15) | 0.05 (-0.11; 0.21) | 0.08 (-0.09; 0.24) |

| Low | 0.03 (-0.28; 0.35) | -0.03 (-0.32; 0.26) | 0.22 (0.05; 0.39)* | 0.22 (0.04; 0.40)* | |

| HannumEAA | LevineEAA | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Education (ref: High) | Medium | 0.32 (0.14; 0.49)*** | 0.27 (0.08; 0.46)** | 0.50 (0.22; 0.79)*** | 0.31 (-0.05; 0.67)+ |

| Low | 0.34 (0.17; 0.52)*** | 0.31 (0.14; 0.48)*** | 0.84 (0.50; 1.17)*** | 0.60 (0.25; 0.94)*** | |

| Smoking (ref: Never) | Former | 0.04 (-0.08; 0.16) | 0.01 (-0.12; 0.13) | 0.60 (0.37; 0.84)*** | 0.52 (0.28; 0.77)*** |

| Current | 0.24 (0.06; 0.42)** | 0.17 (0.00; 0.35)* | 1.57 (1.31; 1.82)*** | 1.41 (1.14; 1.67)*** | |

| Obesity (ref: BMI < 25) | BMI < 30 | 0.17 (0.05; 0.28)** | 0.15 (0.03; 0.27)* | 0.37 (0.13; 0.62)** | 0.33 (0.11; 0.55)** |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 0.22 (0.07; 0.36)** | 0.20 (0.05; 0.34)* | 1.08 (0.79; 1.37)*** | 1.01 (0.74; 1.28)*** | |

| Alcohol (ref: Abstainer) | Occasional | -0.05 (-0.19; 0.09) | 0.03 (-0.11; 0.17) | -0.08 (-0.36; 0.20) | 0.10 (-0.14; 0.34) |

| Habitual | 0.14 (-0.03; 0.31) | 0.21 (0.04; 0.39)* | 0.88 (0.49; 1.26)*** | 0.91 (0.57; 1.25)*** | |

| Physical activity (ref: High) | Medium | 0.07 (-0.08; 0.22) | 0.07 (-0.07; 0.20) | 0.16 (-0.17; 0.49) | 0.20 (-0.04; 0.44) |

| Low | 0.08 (-0.15; 0.32) | 0.05 (-0.20; 0.30) | 0.42 (-0.12; 0.96) | 0.31 (-0.13; 0.74) | |

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05; + p < 0.10

Model 1 includes age, sex, and cohort specific covariates; Model 2 includes additional adjustment for education, smoking, BMI, alcohol and physical activity.

For the three epigenetic clocks, the estimated differences presented in Table 2 (βs) represent the change in biological age (in years) compared with the reference group. Accordingly, the estimated effects of risk factors on SEMs were re-scaled to be expressed in years as for the three epigenetic clocks using a two-step approach based on the Cohen’s D statistic, described in the supplementary text.

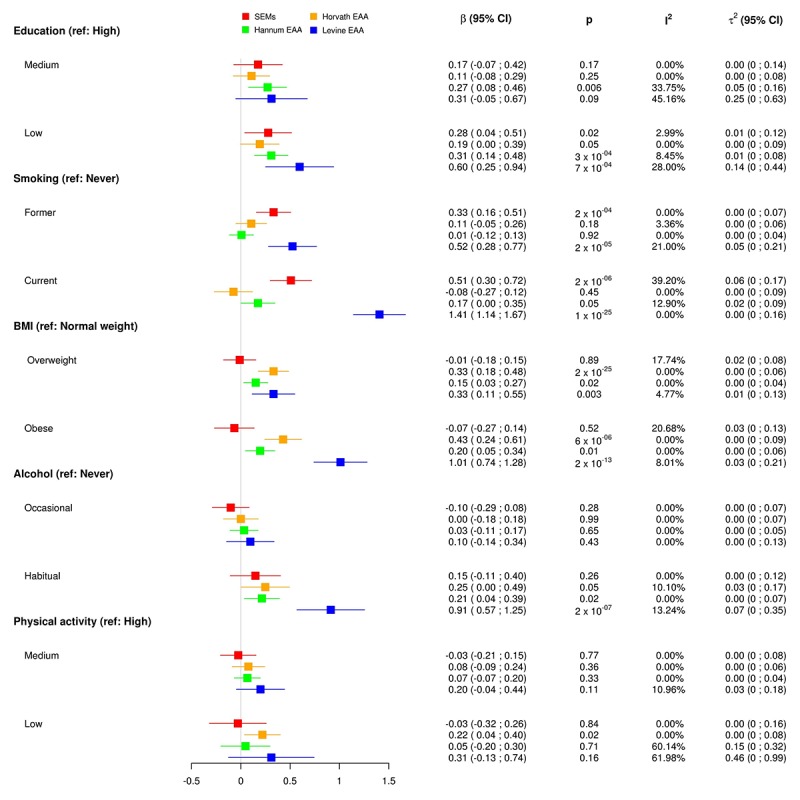

Education: The level of education was significantly associated with the four biomarkers investigated. In Model 1 (minimally adjusted), lower educated individuals had a higher number of SEMs β = 0.34 (95% CI 0.11; 0.58), higher Horvath EAA β = 0.22 (0.03; 0.41), higher Hannum EAA β = 0.34 (0.17; 0.52), and higher Levine EAA β = 0.84 (0.50; 1.17), compared with the higher educated group who constituted the reference category. The observed associations were still significant after the inclusion of smoking, BMI, alcohol and physical activity in the regression models (Model 2), but the estimated effects were moderately reduced. Comparing the two extreme categories (low vs. high education) the estimated effects were: SEMs β = 0.28 (0.04; 0.51), Horvath EAA β = 0.19 (0.00; 0.39), Hannum EAA β = 0.31 (0.14; 0.48), and Levine EAA β = 0.60 (0.25; 0.94) in the full multivariable adjusted models. Interestingly, the intermediate education group ranked between the high and low education group supporting a dose-response effect (Table 2).

Other modifiable risk factors: Current smokers had a higher number of SEMs, higher Hannum EAA and higher Levine EAA compared with never smokers. The estimated effects were slightly reduced in Model 2 compared with Model 1 when adjusted additionally for other covariates. Further, former smokers had intermediate outcomes between never and current smokers (Table 2). The estimated effect size of the association between smoking and epigenetic aging biomarkers was comparable to those observed for education, except for the magnitude of the association with Levine EAA, which was significantly higher: β = 1.57 (1.31; 1.82) in Model 1; β = 1.41 (1.14; 1.67) in Model 2. A similar pattern of associations was observed looking at the effects of obesity on epigenetic aging biomarkers. Obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30) had higher Horvath EAA, higher Hannum EAA, and higher Levine EAA. As previously described for education and smoking, the effects estimated in Model 2 were slightly lower compared with Model 1, and a dose-response association was observed. The estimated effects of obesity were comparable to those of education except for Levine EAA, which was significantly higher: β = 1.08 (0.79; 1.37) in Model 1; β = 1.01 (0.74; 1.28) in Model 2. Looking at alcohol intake, we did not observe any significant difference comparing abstainers and occasional drinkers, but habitual drinkers had higher Horvath EAA, Hannum EAA and Levine EAA. As observed for the other risk factors, the higher estimated effects were observed for Levine’s indicator: β = 0.88 (0.49; 1.26) in Model 1; β = 0.91 (0.57; 1.25) in Model 2. Finally, low physical activity was associated with higher Horvath EAA in both Model 1 β = 0.22 (0.05; 0.39) and Model 2 β = 0.22 (0.04; 0.40).

Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of the results (Model 2) using forest plot which allows one to compare the effect of each risk factor considered in the present paper on the four DNAm outcomes.

Figure 1.

Effect sizes (interpretable as years of increasing/decreasing epigenetic age) of the association between different risk factors and four epigenetic aging biomarkers: total number of stochastic epigenetic mutations (SEMs, red), Horvath epigenetic age acceleration (orange), Hannum epigenetic age acceleration (green) and Levine epigenetic age acceleration next-generation clock (blue).

In sensitivity analyses, we examined the white blood cell (WBC) adjusted epigenetic aging measures (described in Methods), and found similar associations as the ones described above (Table S1). Further, for each risk factor, we evaluated the interaction with age and sex. Our results indicated no significant differences in associations between men and women, whereas we found a significant interaction with age for the association of SEMs with education, smoking, and obesity, with a significantly stronger effect in older individuals (Table S2).

We examined whether SEMs were randomly distributed across the genome or are enriched in functional genomic regions. We observed overlap between the genomic position of SEMs and regions associated with open chromatin states, and shores (p=0.03, p=0.02 respectively, Table S3). Considering the categories defined by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project with Chromatin ImmunoPrecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-Seq) experiments on human embryonic stem cells (hESC), we found enrichment of SEMs in ‘inactive/poised promoters’ (p<0.0001, Table S4), ‘heterochromatin/low signal/CNV’ (p<0.0001, Table S4), and ‘Polycomb-repressed’ regions (p=0.001, Table S4). Furthermore, we found significant overlap with transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) targeted by two members of the Polycomb repressive complex-2 (PRC2): EZH2 and SUZ12 (p<0.0001, Table S5).

DISCUSSION

Social inequalities in health have been extensively reported and accelerated age-dependent DNAm dysregulation has been proposed as one of the biomolecular mechanisms mediating this association [5,24,25]. In this study, we examined the effect on DNAm biomarkers of aging of being in the low education group compared with those of other lifestyle-related risk factors: smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and low levels of physical activity. We used education as the proxy for SEP as it was the only socioeconomic indicator that was available in all the cohorts and it is usually completed before the onset of many chronic diseases, therefore reducing the risk of reverse causation [26]. Lower educational attainment was associated with EAA according to the ‘first generation’ clocks including Horvath’s and Hannum’s. However, previously it was not clear whether the observed associations depend on other factors associated with low education [6,27]. For example, Karlsson Linnér and colleagues argue that the association of educational attainment and epigenetic aging is mainly mediated by maternal smoking during pregnancy and smoking during adulthood [6]. To clarify this issue and to increase the epidemiological evidence in the field, we have examined four biomarkers of age-dependent DNAm dysregulation: the total number of SEMs and three epigenetic clocks (Horvath, Hannum and Levine).

Although all the biomarkers are related to aging, they did not show the same pattern of associations with risk factors, intermediate traits and diseases [28,29], suggesting that these biological age predictors may reflect different facets of the aging process. The total number of SEMs takes into account whole-genome epigenetic deregulation during aging, a process known as ‘epigenetic drift’, and has been proposed as a biomarker of exposure-related accumulation of DNA damage during the lifespan [20]. It is necessary to clarify that the word ‘epimutation’ is sometimes used in a manner that can be misinterpreted. Although some literature uses this term to refer to epigenetic changes driven by genotype differences, the strict definition of epimutation is a heritable change in gene activity that is not associated with a DNA mutation, but rather, with gain or loss of DNA methylation or other heritable modifications of chromatin [30]. Contrary to the definition of genetic mutations, epimutations are defined as potentially (but not necessarily) reversible changes in gene activity not involving DNA mutations, but rather, gain or loss of DNA methyl groups conserved in cells through mitosis [20,30,31].

In contrast, Horvath’s epigenetic clock is based on DNAm levels at a small subset of CpG sites and is thought to reflect the biological age of different tissues, while Hannum’s epigenetic clock is specific to blood samples. Finally, Levine’s next-generation clock is computed using a subset of CpGs that were associated with several clinical measures representing the health status of an individual and has been proposed as a biomarker of the individual ‘phenotypic age’ [15]. Accordingly, Levine’s measure of age acceleration tends to be more variable than the first-generation clocks (Horvath and Hannum) as evidenced by the finding that the associations based on this marker showed, in general, a higher degree of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis measured with the I2 and τ2 statistics.

Our results from this meta-analysis of more than 16,000 individuals support our working hypothesis. We found that the four aging biomarkers were associated with different sets of risk factors and that the magnitude of the associations differed depending on the epigenetic aging index. We compared the effects of two nested models: the first minimally adjusted model included age, sex and cohort-specific covariates as adjustments; the second (fully adjusted model) was adjusted for all of the risk factors. We did not observe significant differences comparing estimates from the two models (Table 2), supporting the robustness of the results presented. Interestingly, the effect of low education was independent from the other risk factors examined, as it was significant in both the minimally adjusted and fully adjusted models; and the effect sizes were comparable to that of the other risk factors examined, with the exception of smoking, which had an appreciably larger impact on SEMs and Levine’s measure. Two previous studies from our group that evaluated the association of low SEP with mortality and physical functioning documented strong patterning by SEP [32,33]. The current study provides evidence of the potential role of epigenetic modifications as mediators of the association of low SEP and unhealthy lifestyle habits with adverse outcomes at older ages, and further underscores the importance of considering SEP as an important life course risk factor for premature biological aging.

In sensitivity analyses, we also investigated alternative measures of the epigenetic aging biomarkers corrected for the proportion of WBC (estimated from whole-genome DNAm data). Chen and colleagues refer to the WBC-adjusted epigenetic aging as an ‘intrinsic’ measure of biological aging, which captures cell-intrinsic properties of the aging process, that exhibit some preservation across various cell types and organs [34]. Our results indicate no significant differences in the results using ‘extrinsic’ (non-WBC-adjusted) vs ‘intrinsic’ measures. Similarly, stratified analyses by sex indicated no differential effect between men and women.

Finally, we evaluated the potential differential effects of risk factors by (chronological) age group. We found that the effect of education, smoking and BMI on the total number of SEMs, and the effect of smoking on Hannum EAA was significantly greater for older individuals. These results agree with the ‘epigenetic memory’ hypothesis according to which epigenetic aging biomarkers, particularly SEMs, could reflect the accumulation of deleterious exposures during the lifespan [35].

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in DNAm dysregulation during aging we investigated whether SEMs occurred randomly in the DNA sequence or were enriched in regulatory regions. Our findings confirmed that epimutations preferentially occur in DNA sequences associated with open chromatin (Table S3), as previously observed by Ong et al. [36]. Furthermore, SEMs were enriched in transcriptionally silenced genomic regions such as ‘inactive promoters’, ‘heterochromatin/low signal/copy number variants (CNV)’, and ‘Polycomb-repressed’ regions (Table S4). Specifically, SEMs were more likely to occur in transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) targeted by two members of Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2): EZH2 and SUZ12 (Table S5). The role of PCR2 proteins and EZH2 specifically in aging and age-related diseases has been extensively investigated in recent years. Targets of PRC2 proteins are enriched for tumor suppressor genes and genes related to mental/neurodegenerative disorders [37–39], providing a link between aging, age-related DNAm modifications and age-related diseases. As an example, downregulations of EZH2 and SUZ12 have been associated with dysregulation of several PRC2 targets including p53, a well-known tumor suppressor gene [40]. These results underscore the imperative for further research aimed at identifying disease-specific epimutation signatures.

In conclusion, we have shown that SEP is associated with different biomarkers of biological (epigenetic) aging, which may represent complementary aspects of the aging process. On average, the impact of low education was comparable with that of other lifestyle-related risk factors, with the exception of smoking, for which the effect was more pronounced. Levine’s second-generation clock was more strongly associated with education and the other risk factors (smoking, obesity and alcohol intake) compared with the first-generation epigenetic clocks and epimutation biomarkers. This result is not wholly unexpected because Levine’s indicator was explicitly designed with a two-step procedure to include both CpG sites associated with aging per se, and CpG sites predictive of mortality and associated with biomarkers of chronic diseases. Given the above, Levine’s epigenetic clock appeared to be a strong candidate for future studies aiming at disentangling the biological pathways underlying social inequalities in healthy aging and longevity. We confirmed in a very large cross-cohort, cross-country sample, previous observations of ‘accelerated aging’ in individuals of low SEP [6,15]. To the best of our knowledge this is also the first study showing that i) socioeconomic status is associated with the total number of stochastic epimutations, which in turn is a biomarker of adverse health outcomes at older ages; and ii) the impact of low socioeconomic status on age-related epigenetic biomarkers is comparable to that of the major lifestyle-related and modifiable risk factors for age related diseases, with the exception of smoking which had a stronger effect on two out of four epigenetic biomarkers investigated.

This study also has limitations: variable collection and classification were not done in a standardized way for all the cohorts. Similarly, for DNA methylation data, each cohort used its own method for data normalization and batch effect removal. To avoid over-estimation of the effects of education and other risk factors on epigenetic aging biomarkers, we used a REML method that incorporates random study effects around the overall mean, to obtain robust global estimates in meta-analysis.

Education was the only SEP indicator used in this study. Critical alternative SEP indicators like income or occupational position were not available in all of the cohorts used in this meta-analysis. We chose to consider all the variables as categorical, with three levels each. On the one hand, this procedure helped us to compare the effects of low education with that of other risk factors, but on the other hand, could lead to a reduction in statistical power to detect significant associations. The lack of association of epigenetic aging measures with low physical activity is not in line with previous literature [27] which might be explained by heterogeneity in the variable definition across cohorts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participating cohorts

We obtained summary-level association statistics from 17 independent cohort studies located in Europe, the United States and Australia (Table 1). The total sample size includes 16,245 individuals of recent European ancestry. All participants provided written informed consent, and all contributing cohorts confirmed compliance with their Local Research Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards. Each risk factor was treated as a categorical variable with three categories each; education: ‘High’ (reference), ‘Medium’, ‘Low’; smoking: ‘Never’ (reference), ‘Former’, ‘Current’; obesity: ‘Normal weight (BMI ≤ 25, reference)’, ‘Overweight (25 < BMI ≤ 30)’, ‘Obese (BMI > 30)’; alcohol consumption: ‘Abstainers’ (reference), ‘Occasional drinkers’, ‘Habitual drinkers’; physical activity: ‘High’ (reference), ‘Medium’, ‘Low’ (see the supplementary text for the definition of the categories).

Identification of stochastic epigenetic mutations

We identified SEMs based on the procedure described by Gentilini et al. [18]. Briefly, for each CpG, considering the distribution of DNAm beta values across all samples, we computed the interquartile range (IQR) - difference between the third quartile (Q3) and the first quartile (Q1) - and we defined a SEM as a methylation value lower than Q1-(3×IQR) or greater than Q3+(3×IQR). Finally, for each individual, we computed the total number of SEMs across all CpGs. Since the total number of SEMs increased exponentially with age, we used a logarithmic transformation of the outcome for all the analyses. In sensitivity analyses, we computed the same measure corrected for potential confounding by differential WBC proportions among individuals. Specifically, for each CpG we calculated the residuals from the regression of DNAm beta values on estimated WBC fractions, and then applied the same procedure described above.

Computation of epigenetic clock measures

We computed the epigenetic age acceleration (AA) measures according to the algorithm described by Horvath [11]. Briefly, DNAm age was calculated as a weighted average of 353 age-related CpGs (Horvath DNAm age), 71 blood specific age-related CpGs (Hannum DNAm age), and 513 phenotypic age-related CpGs (Levine DNAm age) respectively. Weights were obtained using a penalized regression model (Elastic-net regularization) [11]. Age acceleration (AA) was defined as the difference between epigenetic and chronological age. Since AA may be correlated with chronological age, the ‘extrinsic’ EAA is defined as the residuals of AA on age. For sensitivity analyses, we also computed the ‘intrinsic’ epigenetic age acceleration (IEAA), defined as the residuals from the linear regression of AA on chronological age and WBC percentages [34]. Positive values of EAA (which is by definition independent of age) indicate accelerated aging and negative values decelerated aging.

Association of epigenetic aging measures with risk factors

We investigated the association of four biological (epigenetic) aging biomarkers with education, smoking, obesity, alcohol and physical activity using each epigenetic measure as the outcome and risk factors as predictors in linear regression models. For each outcome and each risk factor, we ran two regression models. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex and cohort-specific covariates only (see the supplementary text). Model 2 included additional adjustment for education, smoking, BMI, alcohol intake, physical activity, to derive the mutually adjusted estimate for each risk factor considered in the present paper.

Each cohort provided the results of the analyses as point estimates and 95% confidence intervals based on an R script shared with all the data analysts (available in the Supplementary Materials). The pooled estimated association of risk factors with each outcome were obtained by random effect maximum likelihood (REML) meta-analysis using the R package metafor [41]. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 and τ2 statistics.

SEMs enrichment analysis

The genomic locations of SEMs were annotated by merging the Illumina information on the chromosomal position of each probe with ENCODE/NIH Roadmap ChIP-Seq data for chromatin states and transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) in hESC [42–44]. We investigated whether SEMs were randomly distributed across the genome, or were enriched in functional genomic regions using the procedure implemented in the R package regioneR [45]. Briefly, the algorithm is specifically designed to test whether a set of genomic loci significantly overlap with a set of genomic regions, and includes a permutation procedure that controls for the type I error rate.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

This research was supported by the ‘Lifepath’ grant to Paolo Vineis at Imperial College, London, Silvia Polidoro at the Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM). The Airwave Health Monitoring Study is funded by the Home Office (grant number 780- TETRA) with additional support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre. The Airwave Study uses the computing resources of the UK MEDical BIOinformatics partnership (UK MED-BIO supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/L01632X/1). The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the Municipality of Rotterdam. The DNA methylation data was funded by the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus Medical Center, and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO; project number 184021007) and made available as a Rainbow Project (RP3; BIOS) of the Biobanking and Biomolecular Research Infrastructure Netherlands (BBMRI-NL). TILDA project was supported by the Irish Government, the Atlantic Philanthropies, and Irish Life plc. The SKIPOGH study was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (FN 33CM30-124087); DNA methylation data in the SKIPOGH data was funded by the Swiss national Science Foundation (AmbizioneGrant n° PZ00P3_167732 to Silvia Stringhini) and European commission and the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation - SERI (Horizon 2020 grant n° 633666). We are grateful to all the participants of NICOLA, Dr Laura Smyth and the NICOLA team, which includes nursing staff, research scientists, clerical staff, computer and laboratory technicians, managers and receptionists. This work was supported by the following funders who provide core financial support for the NICOLA Study: the Atlantic Philanthropies; the Economic and Social Research Council; the UKCRC Centre of Excellence for Public Health Northern Ireland; the Centre for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland; the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister; the Health and Social Care Research and Development Division of the Public Health Agency; the Wellcome Trust/Wolfson Foundation; and Queen’s University Belfast. The MCCS component of this work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, grants 1074383 and 1106016). MCCS cohort recruitment was funded by VicHealth and Cancer Council Victoria. The MCCS was further supported by NHMRC grants 209057 and 396414 and by infrastructure provided by Cancer Council Victoria, and the methylation studies were supported by NHMRC grants 1011618, 1026892, 1027505, 1050198, 1043616, 1074383 and 1088405. The Young Finns Study has been financially supported by the Academy of Finland: grants 286284, 134309 (Eye), 126925, 121584, 124282, 129378 (Salve), 117787 (Gendi), and 41071 (Skidi); the Social Insurance Institution of Finland; Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Kuopio, Tampere and Turku University Hospitals (grant X51001); Juho Vainio Foundation; Paavo Nurmi Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Finnish Cultural Foundation; The Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Wihuri Foundation (for L-PR); Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation; Emil Aaltonen Foundation; Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Diabetes Research Foundation of Finnish Diabetes Association; and EU Horizon 2020 (grant 755320 for TAXINOMISIS); and European Research Council (grant 742927 for MULTIEPIGEN project); Tampere University Hospital Supporting Foundation. DNA methylation data for the TERRE study was funded through the multilateral France-Germany-Canada Call for International proposals 2015 on "Epigenomics of complex diseases" (Agence nationale de la recherche grant ANR-15-EPIG-0001) as part of the DECIPHER-PD project. Oliver Robinson was supported by a MRC Early Career Fellowship. Carolina Ochoa-Rosales work was funded by the CONICYT PAI/INDUSTRIA 72170524, Chile. Cathal McCrory is supported by a HRB Emerging Investigator Award (EIA-2017-12). We are grateful to all the participants of NICOLA, and the NICOLA team, which includes nursing staff, research scientists, clerical staff, computer and laboratory technicians, managers and receptionists.

42The Lifepath partners include in alphabetic order: Jan Alberts, Harri Alenius, Mauricio Avendano, Valeria Baltar, Mel Bartley, Henrique Barros, Michele Bellone, Eloise Berger, David Blane, Murielle Bochud, Giulia Candiani, Cristian Carmeli, Luca Carra, Raphaele Castagné, Marc Chadeau-Hyam, Sergio Cima, Françoise Clavel-Chapelon, Giuseppe Costa, Emilie Courtin, Cyrille Delpierre, Angelo D'Errico, Manolis Dermitzakis, Pierre-Antoine Dugué, Marko Elovainio, Paul Elliott, Guy Fagherazzi, Giovanni Fiorito, Silvia Fraga, Martina Gandini, Valérie Garès, Pascale Gerbouin-Rerolle, Graham Giles, Marcel Goldberg, Dario Greco, Idris Guessous, Jose Haba-Rubio, Raphael Heinzer, Allison Hodge, Stephane Joost, Maryam Karimi, Michelle Kelly-Irving, Mika Kähönen, Piia Karisola, Leyla Khenissi, Mika Kivimaki, Vittorio Krogh, Jessica Laine, Thierry Lang, Audrey Laurent, Richard Layte, Benoit Lepage, Dori Lorsch, Frances MacGuire, Giles Machell, Johan Mackenbach, Michael Marmot, Carlos de Mestral, Cathal McCrory, Cynthia Miller, Roger Milne, Peter Muennig, Wilma Nusselder, Salvatore Panico, Dusan Petrovic, Lourdes Pilapil, Silvia Polidoro, Martin Preisig, Laura Pulkki-Råback, Olli Raitakari, Ana Isabel Ribeiro, Fulvio Ricceri, Paolo Recalcati, Erica Reinhard, Oliver Robinson, Jose Rubio Valverde, Severine Saba, Carlotta Sacerdote, Frank Santegoets, Roberto Satolli, Terrence Simmons, Gianluca Severi, Martin J Shipley, Silvia Stringhini, Adam Tabak, Vesa Terhi, Joannie Tieulent, Rosario Tumino, Salvatore Vaccarella, Federica Vigna-Taglianti, Paolo Vineis, Peter Vollenweider, Nicolas Vuilleumier, Marie Zins.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mackenbach JP, Valverde JR, Artnik B, Bopp M, Brønnum-Hansen H, Deboosere P, Kalediene R, Kovács K, Leinsalu M, Martikainen P, Menvielle G, Regidor E, Rychtaříková J, et al. Trends in health inequalities in 27 European countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018; 115:6440–45. 10.1073/pnas.1800028115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artazcoz L, Rueda S. Social inequalities in health among the elderly: a challenge for public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007; 61:466–67. 10.1136/jech.2006.058081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, Brunner E, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA. 2010; 303:1159–66. 10.1001/jama.2010.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunliffe VT. The epigenetic impacts of social stress: how does social adversity become biologically embedded? Epigenomics. 2016; 8:1653–69. 10.2217/epi-2016-0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorito G, Polidoro S, Dugué PA, Kivimaki M, Ponzi E, Matullo G, Guarrera S, Assumma MB, Georgiadis P, Kyrtopoulos SA, Krogh V, Palli D, Panico S, et al. Social adversity and epigenetic aging: a multi-cohort study on socioeconomic differences in peripheral blood DNA methylation. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:16266. 10.1038/s41598-017-16391-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlsson Linnér R, Marioni RE, Rietveld CA, Simpkin AJ, Davies NM, Watanabe K, Armstrong NJ, Auro K, Baumbach C, Bonder MJ, Buchwald J, Fiorito G, Ismail K, et al. An epigenome-wide association study meta-analysis of educational attainment. Mol Psychiatry. 2017; 22:1680–90. 10.1038/mp.2017.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor SE, Repetti RL, Seeman T. Health psychology: what is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annu Rev Psychol. 1997; 48:411–47. 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones MJ, Goodman SJ, Kobor MS. DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell. 2015; 14:924–32. 10.1111/acel.12349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng SC, Widschwendter M, Teschendorff AE. Epigenetic drift, epigenetic clocks and cancer risk. Epigenomics. 2016; 8:705–19. 10.2217/epi-2015-0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teschendorff AE, West J, Beck S. Age-associated epigenetic drift: implications, and a case of epigenetic thrift? Hum Mol Genet. 2013; 22:R7–15. 10.1093/hmg/ddt375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013; 14:R115. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, Zhang L, Hughes G, Sadda S, Klotzle B, Bibikova M, Fan JB, Gao Y, Deconde R, Chen M, Rajapakse I, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell. 2013; 49:359–67. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Declerck K, Vanden Berghe W. Back to the future: epigenetic clock plasticity towards healthy aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018; 174:18–29. 10.1016/j.mad.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugue PA, Bassett JK, Joo JE, Baglietto L, Jung CH, Ming Wong E, Fiorito G, Schmidt D, Makalic E, Li S, Moreno-Betancur M, Buchanan DD, Vineis P, et al. Association of DNA methylation-based biological age with health risk factors, and overall and cause-specific mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2018; 187:529–38. 10.1093/aje/kwx291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, Chen BH, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, Hou L, Baccarelli AA, Stewart JD, Li Y, Whitsel EA, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2018; 10:573–91. 10.18632/aging.101414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slieker RC, van Iterson M, Luijk R, Beekman M, Zhernakova DV, Moed MH, Mei H, van Galen M, Deelen P, Bonder MJ, Zhernakova A, Uitterlinden AG, Tigchelaar EF, et al. , and BIOS consortium. Age-related accrual of methylomic variability is linked to fundamental ageing mechanisms. Genome Biol. 2016; 17:191. 10.1186/s13059-016-1053-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teschendorff AE, Widschwendter M. Differential variability improves the identification of cancer risk markers in DNA methylation studies profiling precursor cancer lesions. Bioinformatics. 2012; 28:1487–94. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentilini D, Garagnani P, Pisoni S, Bacalini MG, Calzari L, Mari D, Vitale G, Franceschi C, Di Blasio AM. Stochastic epigenetic mutations (DNA methylation) increase exponentially in human aging and correlate with X chromosome inactivation skewing in females. Aging (Albany NY). 2015; 7:568–78. 10.18632/aging.100792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentilini D, Scala S, Gaudenzi G, Garagnani P, Capri M, Cescon M, Grazi GL, Bacalini MG, Pisoni S, Dicitore A, Circelli L, Santagata S, Izzo F, et al. Epigenome-wide association study in hepatocellular carcinoma: identification of stochastic epigenetic mutations through an innovative statistical approach. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:41890–902. 10.18632/oncotarget.17462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita S, Kishino T, Takahashi T, Shimazu T, Charvat H, Kakugawa Y, Nakajima T, Lee YC, Iida N, Maeda M, Hattori N, Takeshima H, Nagano R, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in normal tissues have differential impacts on cancer risk among tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018; 115:1328–33. 10.1073/pnas.1717340115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haque MM, Nilsson EE, Holder LB, Skinner MK. Genomic Clustering of differential DNA methylated regions (epimutations) associated with the epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease and phenotypic variation. BMC Genomics. 2016; 17:418. 10.1186/s12864-016-2748-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin MK, Chen E, Ross KM, McEwen LM, Maclsaac JL, Kobor MS, Miller GE. Early-life socioeconomic disadvantage, not current, predicts accelerated epigenetic aging of monocytes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018; 97:131–34. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes A, Smart M, Gorrie-Stone T, Hannon E, Mill J, Bao Y, Burrage J, Schalkwyk L, Kumari M. Socioeconomic position and DNA Methylation age acceleration across the lifecourse. Am J Epidemiol. 2018; 187:2346–54. 10.1093/aje/kwy155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller GE, Yu T, Chen E, Brody GH. Self-control forecasts better psychosocial outcomes but faster epigenetic aging in low-SES youth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015; 112:10325–30. 10.1073/pnas.1505063112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simons RL, Lei MK, Beach SR, Philibert RA, Cutrona CE, Gibbons FX, Barr A. Economic hardship and biological weathering: the epigenetics of aging in a U.S. sample of black women. Soc Sci Med. 2016; 150:192–200. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox JW. Social class, mental illness, and social mobility: the social selection-drift hypothesis for serious mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 1990; 31:344–53. 10.2307/2136818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quach A, Levine ME, Tanaka T, Lu AT, Chen BH, Ferrucci L, Ritz B, Bandinelli S, Neuhouser ML, Beasley JM, Snetselaar L, Wallace RB, Tsao PS, et al. Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging (Albany NY). 2017; 9:419–46. 10.18632/aging.101168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, Hägg S. Biological Age Predictors. EBioMedicine. 2017; 21:29–36. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018; 19:371–84. 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oey H, Whitelaw E. On the meaning of the word ‘epimutation’. Trends Genet. 2014; 30:519–20. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peltomäki P. Mutations and epimutations in the origin of cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2012; 318:299–310. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, Avendaño M, Muennig P, Guida F, Ricceri F, d’Errico A, Barros H, Bochud M, Chadeau-Hyam M, Clavel-Chapelon F, Costa G, et al. , and LIFEPATH consortium. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet. 2017; 389:1229–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, Avendaño M, McCrory C, d’Errico A, Bochud M, Barros H, Costa G, Chadeau-Hyam M, Delpierre C, Gandini M, Fraga S, et al. , and LIFEPATH Consortium. Socioeconomic status, non-communicable disease risk factors, and walking speed in older adults: multi-cohort population based study. BMJ. 2018; 360:k1046. 10.1136/bmj.k1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen BH, Marioni RE, Colicino E, Peters MJ, Ward-Caviness CK, Tsai PC, Roetker NS, Just AC, Demerath EW, Guan W, Bressler J, Fornage M, Studenski S, et al. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging (Albany NY). 2016; 8:1844–65. 10.18632/aging.101020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vineis P, Chatziioannou A, Cunliffe VT, Flanagan JM, Hanson M, Kirsch-Volders M, Kyrtopoulos S. Epigenetic memory in response to environmental stressors. FASEB J. 2017; 31:2241–51. 10.1096/fj.201601059RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ong ML, Holbrook JD. Novel region discovery method for Infinium 450K DNA methylation data reveals changes associated with aging in muscle and neuronal pathways. Aging Cell. 2014; 13:142–55. 10.1111/acel.12159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zingg D, Debbache J, Schaefer SM, Tuncer E, Frommel SC, Cheng P, Arenas-Ramirez N, Haeusel J, Zhang Y, Bonalli M, McCabe MT, Creasy CL, Levesque MP, et al. The epigenetic modifier EZH2 controls melanoma growth and metastasis through silencing of distinct tumour suppressors. Nat Commun. 2015; 6:6051. 10.1038/ncomms7051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Schimmelmann M, Feinberg PA, Sullivan JM, Ku SM, Badimon A, Duff MK, Wang Z, Lachmann A, Dewell S, Ma’ayan A, Han MH, Tarakhovsky A, Schaefer A. Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) silences genes responsible for neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2016; 19:1321–30. 10.1038/nn.4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su SK, Li CY, Lei PJ, Wang X, Zhao QY, Cai Y, Wang Z, Li L, Wu M. The EZH1-SUZ12 complex positively regulates the transcription of NF-κB target genes through interaction with UXT. J Cell Sci. 2016; 129:2343–53. 10.1242/jcs.185546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiogama S, Yoshiba S, Soga D, Motohashi H, Shintani S. Aberrant expression of EZH2 is associated with pathological findings and P53 alteration. Anticancer Res. 2013; 33:4309–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010; 36 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziller MJ, Gu H, Müller F, Donaghey J, Tsai LT, Kohlbacher O, De Jager PL, Rosen ED, Bennett DA, Bernstein BE, Gnirke A, Meissner A. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013; 500:477–81. 10.1038/nature12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, Kellis M, Marra MA, Beaudet AL, Ecker JR, Farnham PJ, Hirst M, Lander ES, et al. , and The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010; 28:1045–48. 10.1038/nbt1010-1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, Bilenky M, Yen A, Heravi-Moussavi A, Kheradpour P, Zhang Z, Wang J, Ziller MJ, Amin V, Whitaker JW, Schultz MD, et al. , and Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015; 518:317–30. 10.1038/nature14248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gel B, Díez-Villanueva A, Serra E, Buschbeck M, Peinado MA, Malinverni R. regioneR: an R/Bioconductor package for the association analysis of genomic regions based on permutation tests. Bioinformatics. 2016; 32:289–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elliott P, Vergnaud AC, Singh D, Neasham D, Spear J, Heard A. The Airwave Health Monitoring Study of police officers and staff in Great Britain: rationale, design and methods. Environ Res. 2014; 134:280–85. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiorito G, Vlaanderen J, Polidoro S, Gulliver J, Galassi C, Ranzi A, Krogh V, Grioni S, Agnoli C, Sacerdote C, Panico S, Tsai MY, Probst-Hensch N, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation mediate the effect of air pollution on cardio- and cerebrovascular disease: A prospective study in nonsmokers. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2018; 59:234–46. 10.1002/em.22153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riboli E, Kaaks R. The EPIC Project: rationale and study design. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 1997. (Suppl 1); 26:S6–14. 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Löw M, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H, and ESTHER study. [Epidemiological investigations of the chances of preventing, recognizing early and optimally treating chronic diseases in an elderly population (ESTHER study)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004; 129:2643–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herder C, Kannenberg JM, Huth C, Carstensen-Kirberg M, Rathmann W, Koenig W, Heier M, Püttgen S, Thorand B, Peters A, Roden M, Meisinger C, Ziegler D. Proinflammatory cytokines predict the incidence and progression of distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy: KORA F4/FF4 Study. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40:569–76. 10.2337/dc16-2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milne RL, Fletcher AS, MacInnis RJ, Hodge AM, Hopkins AH, Bassett JK, Bruinsma FJ, Lynch BM, Dugué PA, Jayasekara H, Brinkman MT, Popowski LV, Baglietto L, et al. Cohort Profile: The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (Health 2020). Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46:1757–1757i. 10.1093/ije/dyx085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bell B, Rose CL, Damon A. The Veterans Administration longitudinal study of healthy aging. Gerontologist. 1966; 6:179–84. 10.1093/geront/6.4.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burns F, Carney GM, Cruise S, Devine P, Devlin A, Donnelly M, French D, Kee F, Montgomery L, O’Reilly D, Scott A, Tully MA. (2017). Early key findings from a study of older people in Northern Ireland. The NICOLA Study. (Belfast: Queen's University, Belfast). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ikram MA, Brusselle GG, Murad SD, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, Goedegebure A, Klaver CC, Nijsten TE, Peeters RP, Stricker BH, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Vernooij MW, Hofman A. The Rotterdam Study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017; 32:807–50. 10.1007/s10654-017-0321-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ackermann-Liebrich U, Kuna-Dibbert B, Probst-Hensch NM, Schindler C, Felber Dietrich D, Stutz EZ, Bayer-Oglesby L, Baum F, Brändli O, Brutsche M, Downs SH, Keidel D, Gerbase MW, et al. , and SAPALDIA Team. Follow-up of the Swiss Cohort Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA 2) 1991-2003: methods and characterization of participants. Soz Praventivmed. 2005; 50:245–63. 10.1007/s00038-005-4075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pruijm M, Ponte B, Ackermann D, Paccaud F, Guessous I, Ehret G, Pechère-Bertschi A, Vogt B, Mohaupt MG, Martin PY, Youhanna SC, Nägele N, Vollenweider P, et al. Associations of urinary uromodulin with clinical characteristics and markers of tubular function in the general population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016; 11:70–80. 10.2215/CJN.04230415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elbaz A, Clavel J, Rathouz PJ, Moisan F, Galanaud JP, Delemotte B, Alpérovitch A, Tzourio C. Professional exposure to pesticides and Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2009; 66:494–504. 10.1002/ana.21717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kearney PM, Cronin H, O’Regan C, Kamiya Y, Savva GM, Whelan B, Kenny R. Cohort profile: the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2011; 40:877–84. 10.1093/ije/dyr116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Rönnemaa T, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Räsänen L, Pietikäinen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, Taittonen L, Jokinen E, Marniemi J, Jula A, Telama R, Kähönen M, et al. Cohort profile: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2008; 37:1220–26. 10.1093/ije/dym225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.