Abstract

Objective

to determine whether a 4-week postoperative rehabilitation program delivered in Nursing Care Facilities (NCFs) would improve quality of life and mobility compared with receiving usual care.

Design

parallel randomised controlled trial with integrated health economic study.

Setting

NCFs, in Adelaide South Australia.

Subjects

people aged 70 years and older who were recovering from hip fracture surgery and were walking prior to hip fracture.

Measurements

primary outcomes: mobility (Nursing Home Life-Space Diameter (NHLSD)) and quality of life (DEMQOL) at 4 weeks and 12 months.

Results

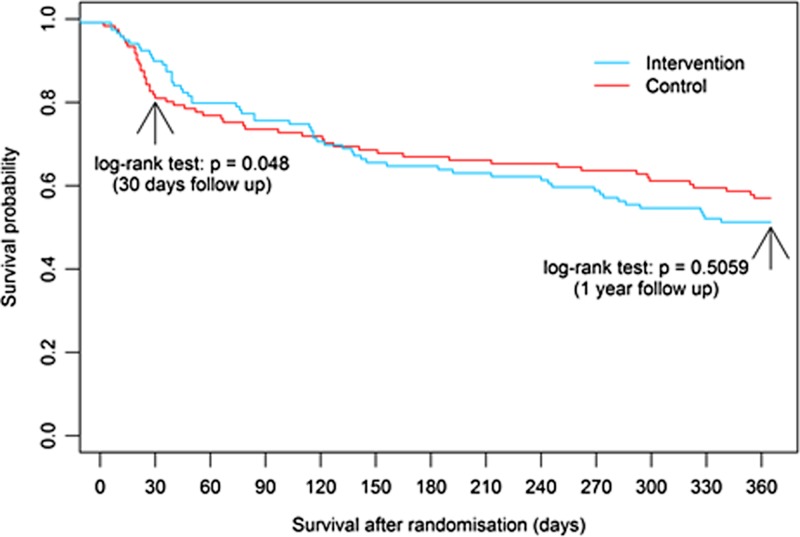

participants were randomised to treatment (n = 121) or control (n = 119) groups. At 4 weeks, the treatment group had better mobility (NHLSD mean difference −1.9; 95% CI: −3.3, −0.57; P = 0.0055) and were more likely to be alive (log rank test P = 0.048) but there were no differences in quality of life. At 12 months, the treatment group had better quality of life (DEMQOL sum score mean difference = −7.4; 95% CI: −12.5 to −2.3; P = 0.0051), but there were no other differences between treatment and control groups. Quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained over 12 months were 0.0063 higher per participant (95% CI: −0.0547 to 0.0686). The resulting incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were $5,545 Australian dollars per unit increase in the NHLSD (95% CI: $244 to $15,159) and $328,685 per QALY gained (95% CI: $82,654 to $75,007,056).

Conclusions

the benefits did not persist once the rehabilitation program ended but quality of life at 12 months in survivors was slightly higher. The case for funding outreach home rehabilitation in NCFs is weak from a traditional health economic perspective.

Trial registration

ACTRN12612000112864 registered on the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Trial protocol available at https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id = 361980

Keywords: hip fracture, rehabilitation, aged care, mobility, quality of life, older people

Key points

A 4-week multidisciplinary postoperative rehabilitation program after hip fracture surgery conducted in nursing care facilities was associated with better mobility and survival at 4 weeks compared with usual care.

The benefits did not persist once the rehabilitation program ended but a small gain in quality of life at 12 months in survivors was seen.

The overall mortality rate was 46% at 12 months.

The outreach rehabilitation program could not be considered cost-effective against current public funding thresholds.

Future trials should explore different approaches to postoperative hip fracture recovery in this group, such as nursing care facility based rehabilitation approaches.

Background

Hip fractures are a common cause of suffering for residents of nursing care facilities (NCFs) and outcomes are poor [1]. Most residents have dementia and are frail. In a retrospective cohort study of 60,111 US Medicare beneficiaries living in nursing homes, only one in five patients who had been fully independent or required limited supervision/assistance walking at baseline survived to regain their pre-fracture level of walking 180 days after fracture [2].

Guidelines for hip fracture management promote prompt surgery, early mobilisation, and a team-based rehabilitation approach to restoring function and mobility [3]. The high risk of death and adverse outcomes means there is uncertainty about the benefits of health service resources allocated to rehabilitation in people living in NCFs [3]. We investigated the feasibility of providing a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and interdisciplinary rehabilitation program which was developed according to clinical guidelines [4, 5]. The aim of the study was to examine if a rehabilitation program in NCFs for people who were recovering from hip fracture surgery improved quality of life and mobility at 4 weeks and 12 months.

Methods/design

See Supplementary material, available at Age and Ageing online for the CONSORT checklist and protocol. The study was approved by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee. A randomised controlled trial with masked outcome assessments was undertaken between June 2012 and December 2014. A computer generated random sequence with random block sizes was used by a pharmacist external to the project to allocate people with a hip fracture, who had been treated surgically into: (a) 4-week ambulatory geriatric rehabilitation program (delivered in the NCF) (b) usual care. Recruitment occurred on acute orthopaedic wards at three South Australian Hospitals.

Participant procedures

Participants were randomised in hospital, the intervention commenced within 24 h of return to the NCF, and on return all residents received usual medical care from their general practitioner. All hospitals had an Orthogeriatrics service that reviewed patients prior to discharge. Inclusion criteria were: a recent hip fracture treated surgically, aged 70 years or older, able to follow a one-step command, living in an NCF prior to injury, ambulant prior to fracture, and ready for discharge, providing self or proxy informed consent (full criteria listed in Supplementary material, available at Age and Ageing online).

Those allocated to the intervention received visits from a hospital outreach team who provided a Comprehensive Geriatrics Assessment, physiotherapy and nutritional assessment and care plan. Physiotherapy included mobility and task specific training, graduated muscle strengthening exercises and training of care staff and family. The geriatrician met families within a fortnight to discuss progress. The intervention was low intensity and involved 13 h of input.

Measurements/procedures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were mobility autonomy (measured using the Nursing Home Life-Space Diameter (NHLSD)) and Quality of Life. The NHLSD has high intra-rater (0.922) and inter-rater (0.951) reliability and moderate positive correlation with other functional characteristics (e.g. social activity participation, dressing,) [6]. It consists of four diameters scored on a scale of 0–5 and weighted, with possible scores ranging from 0 (bed- or chair-bound) to 120 (signifying leaving the facility daily). Care staff were asked to describe the level of independence and hands-on support each participant was receiving at baseline, 4 weeks and 12 months.

Quality of life was assessed with the 28-item DEMQOL and 31-item DEMQOL-Proxy which are condition specific measures designed to measure health-related quality of life for older people with dementia and their carers [7]. At baseline 90 participants completed the DEMQOL and 237 were completed by proxies (in 83 cases both an individual and proxy questionnaires were completed). At 4 weeks, the DEMQOL-Proxy was completed for 199 participants. The overall correlation between scores of the self-completed questionnaires and proxy questionnaires was poor at baseline (r = 0.27538, P = 0.0117) with proxies tending to score quality of life lower than individuals suggesting that different constructs were being measured. Where two questionnaires were available the DEMQOL-Proxy was used. The EuroQol five dimension–five level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) was administered to compare participants’ quality of life with other patient groups internationally [8].

Secondary outcomes

Physical dependency was measured by the Modified Barthel Index [9] and the Functional Recovery Scale [10]. Other measures included cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination: MMSE) [11], confusion or delirium (Confusion Assessment Method) [12], depression (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia) [13], pain (the Pain Assessment In Advanced Dementia scale: PAINAD) [14] and nutrition (The Mini-Nutritional Assessment) [15].

Statistical analysis

To assess minimally important differences in the DEMQOL index score, we needed 98 per group (intervention and control). After allowing for deaths and drop-outs of 20% the estimated sample size was 196*1.2 = 236 (118 per group). The detectable effect size between groups was conservatively selected as small to medium (0.10–0.25) as suggested by Cohen [16]. Calculations were based on two-tailed tests with power of at least 80% and significance level of 0.05.

Outcomes were evaluated using linear mixed models with a time-by-group interaction term. The covariates were group, time, time*group and baseline scores for the outcome variables.

To investigate survival from the randomisation to 4 weeks and 12 months, we used Kaplan–Meier and log rank test to test the between group difference. All data were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle and performed with SAS, v9.3 (SAS institute) and R 3.11.

To assess the incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with usual care we examined incremental cost-effectiveness per unit increase in the NHLSD total score over 1-year follow-up. Utility-based outcomes were incorporated into the analysis, to generate a secondary outcome: incremental cost per Quality adjusted life year (QALY; based on DEMQOL-Proxy values). QALYs were calculated using the area-under-the-curve [17]. Cost effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were constructed, depicting the probability of the intervention being more cost-effective compared with the usual care arm at different willingness-to-pay thresholds (see Supplementary Figures S4 and S5, available at Age and Ageing online) [18]. Further details on the cost effectiveness analysis are provided in the supplementary information.

Results

At the three participating hospitals 2,120 hip fracture patients were screened, 354 were eligible and following consent 240 participated (see Supplementary Figure S1, available at Age and Ageing online). In the majority of cases (97%) consent was obtained from family members due to cognitive impairment. Demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 1). The mean age was 88.6 years (SD: 5.6) and 13% had a prior hip fracture. The majority (87.9%) received surgical treatment within the first 24 h of admission (range: 0–5 days). Baseline pain (PAINAD) scored at rest was low 1.4 (SD: 1.7), only 23 recruits were able to transfer (all with assistance from two people) and 217 participants were either confined to bed or transferred using a hydraulic lifter. Almost all showed evidence of cognitive problems with only two people scoring 26 or above on the MMSE. Eighty-four percent (n = 201) of participants were discharged within 48 h of randomisation. Of the 240 patients, 186 (77.5%) had a recorded diagnosis of dementia (further details in Supplementary material, available at Age and Ageing online).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristic* | Control | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| N1 = 121 | N2 = 119 | |

| Female sex—n (%) | 91 (75.2) | 87 (73.1) |

| Age—n (%) (range: 70–101) | ||

| 70–79 | 8 (6.6) | 8 (6.7) |

| 80–89 | 56 (46.3) | 62 (52.1) |

| 90–95 | 44 (36.4) | 38 (31.9) |

| >95 | 13 (10.7) | 11 (9.2) |

| Age-mean (SD) | 88.6 (5.7) | 88.6 (5.4) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination—mean (SD) | 8.5 (7.6) | 7.5 (8.0) |

| Medication Appropriateness Index—mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.9) | 2.3 (1.8) |

| Delirium—n (%) | 41 (33.9) | 42 (35.3) |

| Previous any fractures—yes (%) | 47 (38.8) | 47 (39.5) |

| Previous hip fractures—yes (%) | 16 (13.1) | 16 (13.6) |

| Type of hip of fracture (at baseline) | ||

| Extracapsular | 58 (47.9) | 52 (43.7) |

| Intracapsular | 63 (52.1) | 67 (56.3) |

| Extracapsular hip fracture-surgery type at baseline (n = 110) | ||

| Sliding hip screw | 8 (13.8) | 15 (28.8) |

| Intramedullary nail | 50 (86.2) | 37 (71.2) |

| Intracapsular hip fracture-surgery type at baseline (n = 130) | ||

| Internal fixation | 18 (28.6) | 15 (22.4) |

| Cemented Hemiarthroplasty | 28 (44.4) | 36 (53.7) |

| Uncemented Hemiarthroplasty | 15 (23.8) | 15 (22.4) |

| Total hip replacement | 2 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) |

| Pre-fracture Mobility Aid indoor | ||

| None | 20 (16.5) | 26 (21.9) |

| Walking stick | 5 (4.1) | 2 (1.7) |

| Walking frame | 96 (79.3) | 89 (74.8) |

| Personal assistance | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) |

| Pre-fracture Mobility Aid Outdoor | ||

| None | 15 (12.4) | 23 (19.3) |

| Walking stick | 4 (3.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Walking frame | 76 (62.8) | 67 (56.3) |

| Personal assistance | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.5) |

| Unable | 25 (20.6) | 25 (21.0) |

| Pre-fracture Mobility Assistance—Indoor | ||

| Independent | 82 (67.8) | 73 (61.3) |

| 1 x LA | 16 (13.2) | 19 (16.0) |

| 1 x MA | 4 (3.3) | 7 (5.9) |

| 1 x S/B | 19 (15.7) | 20 (16.8) |

| Pre-fracture Mobility Assistance—Outdoor | ||

| Independent | 41 (33.9) | 33 (27.7) |

| 1 x LA | 17 (14.1) | 18 (15.1) |

| 1 x MA | 4 (3.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| 1 x S/B | 37 (30.6) | 35 (29.4) |

| 2 x LA | 1 (0.8) | 6 (5.0) |

| Unable | 21 (17.4) | 26 (21.9) |

*There was no significant difference (P < 0.05) between control and intervention groups for all above variables at baseline. Data are mean (SD) or n (%).

At 4 weeks, the treatment group achieved a better mobility score (NHLSD mean difference −1.9; 95% CI: −3.3 to −0.57; P = 0.0055) (Table 2). The treatment group also had better nutritional status than the control group (−0.65; 95% CI: −1.3,−0.05; P = 0.0338).

Table 2.

Baseline and four week data for primary and secondary outcomes

| Outcomes | Control | Intervention | Difference (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nc | Mean (SE) | nc | Mean (SE) | |||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| NHLSD | 121 | 0 (0) | 119 | 0 (0) | _ | _ |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| DEMQOL sum score | 50 | 86.5 (1.2) | 40 | 86.2 (4.4) | 0.30 (−3.4, 4.0) | 0.8711 |

| DEMQOL index (utility) | 50 | 0.80 (0.04) | 40 | 0.79 (0.04) | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.13) | 0.8587 |

| DEMQOL-proxy sum score | 119 | 90.9 (1.0) | 118 | 92.1 (1.0) | −1.1 (−3.8, 1.6) | 0.4141 |

| DEMQOL-proxy index (utility) | 119 | 0.62 (0.02) | 118 | 0.54 (0.02) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.7111 |

| EQ5D5L index (utility) | 119 | 0.22 (0.02) | 119 | 0.23 (0.02) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.7788 |

| 4 Weeks | ||||||

| NHLSD | 96 | 6.3 (0.50) | 107 | 8.2 (0.47) | −1.9 (−3.3, −0.57) | 0.0055 |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| DEMQOL sum score | 45 | 88.3 (1.6) | 49 | 91.0 (1.7) | −2.7 (−7.3, 1.8) | 0.2370 |

| DEMQOL index | 67 | 0.68 (0.05) | 59 | 0.74 (0.04) | −0.06 (−0.20, 0.08) | 0.3896 |

| DEMQOL-proxy sum score | 94 | 93.7 (1.1) | 105 | 94.2 (1.0) | −0.52 (−3.5, 2.4) | 0.7305 |

| DEMQOL-proxy index | 116 | 0.54 (0.02) | 115 | 0.60 (0.02) | −0.06 (−0.11, 0.01) | 0.0784 |

| EQ5D5L index | 118 | 0.38 (0.02) | 115 | 0.43 (0.02) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.01) | 0.1058 |

| 12 Months | ||||||

| NHLSD | 66 | 10.1 (0.60) | 60 | 10.5 (0.63) | 0.37 (−2.1, 1.3) | 0.6777 |

| Quality of life | ||||||

| DEMQOL sum score | 41 | 88.5 (1.6) | 29 | 95.9 (2.0) | −7.4 (−12.5, −2.3) | 0.0051 |

| DEMQOL index | 93 | 0.54 (0.03) | 87 | 0.48 (0.04) | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.19) | 0.3521 |

| DEMQOL-proxy sum score | 66 | 101.9 (1.3) | 60 | 98.7 (1.4) | 3.1 (−0.62, 6.9) | 0.1023 |

| DEMQOL-proxy index | 118 | 0.40 (0.02) | 118 | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.06 (−0.003, 0.13) | 0.0628 |

| EQ5D5L index | 118 | 0.30 (0.02) | 117 | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.06 (−0.006, 0.13) | 0.0739 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| PAINAD | 121 | 1.4 (0.11) | 119 | 1.4 (0.11) | 0.00 (−0.31, 0.31) | 0.9824 |

| Modified Barthel Index | 121 | 9.6 (1.8) | 119 | 9.5 (1.8) | 0.08 (−4.9, 5.1) | 0.9735 |

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | 119 | 10.1 (0.42) | 119 | 10.0 (0.42) | 0.01 (−1.2, 1.2) | 0.9857 |

| Mini-Nutritional Assessment | 121 | 5.4 (0.20) | 119 | 5.3 (0.20) | 0.12 (−0.43, 0.68) | 0.6670 |

| Functional recovery | 121 | 1.8 (0.36) | 119 | 1.8 (0.36) | 0.01 (−0.98, 1.01) | 0.9798 |

| Delirium | 121 | 0.34 (0.04)a | 119 | 0.35 (0.04)a | 0.94 (0.55, 1.6)b | 0.8184 |

| 4 Weeks | ||||||

| PAINAD | 95 | 0.49 (0.13) | 107 | 0.51 (0.12) | −0.02 (−0.34, 0.29) | 0.8998 |

| Modified Barthel Index | 95 | 23.5 (2.0) | 107 | 24.4 (1.9) | −1.0 (−6.4, 4.5) | 0.7267 |

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | 96 | 10.6 (0.47) | 107 | 10.5 (0.44) | 0.15 (−1.1, 1.4) | 0.8097 |

| Mini-Nutritional Assessment | 96 | 6.2 (0.22) | 107 | 6.9 (0.21) | −0.65 (−1.3, −0.05) | 0.0338 |

| Functional recovery | 94 | 5.8 (0.40) | 107 | 6.0 (0.38) | −0.25 (−1.3, 0.84) | 0.6542 |

| Delirium | 95 | 0.13 (0.03) | 107 | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.75 (0.35, 1.6) | 0.4589 |

| 12 Months | ||||||

| PAINAD | 66 | 0.06 (0.15) | 60 | 0.05 (0.16) | 0.01 (−0.42, 0.44) | 0.9645 |

| Modified Barthel Index | 66 | 32.3 (2.4) | 59 | 27.4 (2.5) | 5.0 (−1.9, 11.8) | 0.1533 |

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | 66 | 9.3 (0.56) | 60 | 10.1 (0.59) | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.8) | 0.3262 |

| Mini-Nutritional Assessment | 66 | 8.0 (0.27) | 60 | 8.8 (0.28) | −0.73 (−1.5, 0.03) | 0.0592 |

| Functional recovery | 66 | 7.1 (0.48) | 60 | 6.2 (0.50) | 0.84 (−0.52, 2.2) | 0.2257 |

| Delirium | 66 | 0.18 (0.05)a | 60 | 0.22 (0.05)a | 0.77 (0.33, 1.8)b | 0.5486 |

aPercentage.

bodds ratio.

cFor sum scores, deceased patients were treated as missing, for index scores (utility), patients who were deceased were assigned a zero value.

At 12-month follow-up, the treatment group had better quality of life as measured by DEMQOL sum scores (mean difference = −7.4; 95% CI: −12.5, −2.3; P = 0.0051). There were no other statistically significant differences between treatment and control groups.

At 4 weeks, the death rate was 8% in the intervention group and 18% in the control group (log rank test by the end of 4 weeks P = 0.048), and in the control group the number of deaths increased each week from one death (Week 1) to eight deaths (Week 4) (Figure 1). However, after the rehabilitation program, there was an increase in deaths in the intervention group. After 35 days, there was no statistically significant difference between groups in the probability of survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival probability from randomisation to 12-month follow-up.

Adverse events

In total, 95 nursing home residents sustained one or more falls during the 4-week intervention with 56 people from the intervention group incurring 62.7% (n = 162) of the falls. Twelve people had hospital admissions including three hip fractures. In the usual care group, 39 people fell with 15 (38.5%) requiring hospital admission and one person sustained a hip fracture (see Supplementary material, available at Age and Ageing online).

Economic evaluation

Mean per participant 12-month Australian Medicare costs were higher in the intervention group than in the control arm (by $2,076 per patient) but these differences were not statistically significant (95% CI: −$220–$4,360). Drivers of higher costs in the intervention were the intervention cost itself and higher drug costs. When the adjusted 12-month primary and secondary outcomes in the base case were considered (Supplementary material), the intervention was more effective than the control with participants reporting NHLSD totals scores that were higher by 0.3745 per patient (95% CI: −1.327 to 2.076) and QALYs gained that were higher by 0.0063 per patient (95% CI: −0.0547 to 0.0686). The resulting incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were $5,545 per unit increase in the NHLSD total score (95% CI: $244–$15,159) and $328,685 per QALY gained (95% CI: $82,654–$75,007,056). The ICER based on QALYs is substantially greater than the implicit cost-effectiveness threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained currently applied by regulatory bodies in Australia [19], implying that the intervention would not be considered cost-effective [17].

Discussion

A 4-week multidisciplinary home rehabilitation program reduced mortality and improved mobility and nutritional status in people living in NCFs who had previously been walking but then fractured their hips. However, improvements were not sustained at 12 months. At 12 months, there was a small quality of life improvement in survivors.

The higher health costs associated with improved mobility in the intervention group were modest. However, the 12-month cost effectiveness estimates are prohibitively high at $5,545 per unit improvement in the NHLSD total scores and $328,685 per QALY gained. Estimates of the incremental costs per QALY gained from this trial are much higher than the recommended threshold of $50,000/QALY used in Australia suggesting that providing outreach rehabilitation is not likely to be value for money for a health service. One option to improve the cost effectiveness estimate would be to decrease the rehabilitation costs and extend the period of additional therapy by exploring models of rehabilitation where NCF staff are trained to deliver therapy for longer periods of time. However, for frail older people living in nursing homes where death is a common event and quality of life gains are modest, results of cost effectiveness approaches are unlikely to be favourable and decisions on allocation of resources to this group may need to include consideration of a community’s values. After this trial, a citizens’ jury process was conducted with randomly selected citizens which suggested that the community regards access to recovery or rehabilitation services for nursing home patients as a human rights issue and despite the cost effectiveness analysis would allocate health resources to hip fracture rehabilitation to people in nursing homes [20].

There are difficulties assessing quality of life in very old people with dementia. While the DEMQOL and DEMQOL proxy measures are likely to be accurate measures for quality of life in people living with dementia, the validity of these measures in people without dementia is unclear [21]. The EQ-5D is widely-used in economic evaluations of healthcare and has high reliability and good validity. However, the validity of the EQ-5D for people with moderate to severe dementia is unclear [22].

Our study revealed that people returning to NCFs after hip fracture receive very little support for recovery and it is possible that the initial group difference in mortality resulted from moving and attempting to re-establish mobility and avoiding complications. The high mortality rate in hip fracture patients from NCFs has been previously reported as 45% at 12 months and a combined rate of death or new inability to ambulate of 63% [23].

As the study was undertaken with participants living in NCFs who were mobile pre-fracture the results may not be generalisable to people living in the community or those who had no mobility pre-fracture. There is some evidence of an increased rate of adverse events (falls) in the intervention group. This suggests that the intervention should be applied carefully when trying to re-establish mobility in this group.

The scoring algorithms we used for the EQ-5D-5L, DEMQOL and DEMQOL proxy were from a UK general population sample [24, 25] despite the study taking place in Australia because Australian scoring algorithms were unavailable, as utilities. However, health states have been shown to differ across countries and jurisdictions [26]. Previous studies to investigate the agreement between self- and proxy-rated HRQoL for people with dementia have indicated only a poor-to-moderate level of agreement overall, with proxy assessors tending to report lower HRQoL than individuals themselves [27, 28]. The choice of proxy assessor (e.g. family member, residential care staff member, clinician) has also previously been found to be associated with discrepancies in assessment of HRQoL using the EQ-5D [27, 28]. Despite these shortcomings associated with the use of proxy rating (and whilst it our collective belief that self-assessment of HRQoL is preferable where ever possible), for the conduct of economic evaluation where assessment of HrQoL is required at repeated time intervals over an extended time period proxy assessment is likely to be necessary. As indicated previously, proxy assessment of HRQoL is the most acceptable across the entire range of Alzheimer’s disease severity in terms of validity and reliability in detecting long-term changes relevant to economic evaluations [29].

A limitation of our study was that the UK, rather than Australian, value sets were used to calculate utility scores for both the DEMQOL and EQ-5D instruments as the latter is not yet available. Generally, guidelines recommend using preference weights specific to the jurisdiction of interest as empirical evidence suggests population values may differ for health states across countries, possibly due to cultural differences [30]. Hence, it is important that future research employs Australian general population-specific value sets as these become available.

The current study not only demonstrates the challenges of working with very old people who have high mortality rates but also the difficulties in assessing effective treatments and improvements in quality of life.

Conclusions

A rehabilitation program for older people living in NCFs after hip fracture surgery who were mobile pre-surgery showed improved mobility, nutritional status and survival compared to usual care at 4 weeks. These improvements did not persist at one year but there were small quality of life gains at 12 months in the survivors. The outreach rehabilitation program was not cost-effective. Further studies could investigate whether a longer-term or NCF-based rehabilitation approach following hip fracture is cost-effective.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: M Crotty had completed two previous clinical drug trials on community dwelling hip fracture patients: (1) Novartis (2016–2017) trial to evaluate iv bimagrumab on total lean body mass and physical performance in patients after surgical treatment of hip fracture and (2) Eli Lilly STEADY trial to investigate subcutaneous injections of LY2495655 in older patients who have fallen recently and have muscle weakness. M Chehade has received institutional grants from Stryker to support hip fracture research, but it does not pose a relevant conflict to this study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of Sources of Funding: This study was supported by funding provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Centre on Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People (grant no. GNT9100000). The contents of the published materials are solely the responsibility of the Administering Institution, Flinders University, and the individual authors identified, and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC or any other Funding Bodies or the Funding Partners.

References

- 1. Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003; 51: 364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neuman MD, Silber JK, Magaziner JS, Passarella MA, Mehta S, Werner RM. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) The management of hip fracture in adults. London 2011; Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11968/51532/51532.pdf.

- 4. Crocker T, Forster A, Young J et al. Physical rehabilitation for older people in long-term care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 28: CD004294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care: Improving Outcomes in Hip Fracture Management of Adults. Sydney: Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tinetti ME, Ginter SF. The nursing home life-space diameter. A measure of extent and frequeny of mobility among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38: 1311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mulhern B, Rowen D, Braxier J et al.. Development of DEMQOL-U and DEMQOL-PROXY-U: generation of preference-based indices from DEMQOL AND DEMQOL-PROXY for use in economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2013; 17: 1–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42: 703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Functional recovery after fracture of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994; 76: 751–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12: 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113: 941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alexopoulos G, Abrams R, Young R, Shamolan C. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1988; 23: 271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003; 4: 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nourhashemi F, Guyonnet S, Ousset PJ et al. Mini nutritional assessment and Alzheimer patients. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Clin Perform Programme 1999; 1: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112: 115–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Drummond MF, Sculpher M, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krichbaum K. GAPN postacute care coordination improves hip fracture outcomes. West J Nurs Res 2007; 29: 523–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris AH, Hill SR, Chin G, Li JJ, Walkom E. The role of value for money in public insurance coverage decisions for drugs in Australia: a retrospective analysis 1994-2004. Med Decis Making 2008; 28: 713–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laver K, Gnanamanickam E, Ratcliffe J et al. A citizens jury to inform policy on rehabilitation for people in residential care with hip fracture. Innov Aging 2017; 1: 226. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chua KC, Brown A, Little R et al. Quality-of-life assessment in dementia: the use of DEMQOL and DEMQOL-Proxy total scores. Qual Life Res 2016; 25: 3107–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hounsome N, Orrell M, Edwards RT. EQ-5D as a quality of life measure in people with dementia and their carers: evidence and key issues. Value Health 2011; 14: 390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beaupre LA, Binder EF, Cameron ID et al. Maximising functional recovery following hip fracture in frail seniors. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013; 27: 771–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ 2018; 27: 7–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rowen D, Mulhern B, Banerjee S et al. Estimating preference-based single index measures for dementia using DEMQOL and DEMQOL-Proxy. Value Health 2012; 15: 346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olsen JA, Lamu AN, Cairns J. In search of a common currency: a comparison of seven EQ-5D-5L value sets. Health Econ 2018; 27: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trigg R, Jones RW, Knapp M, King D, Lacey LA. The relationship between changes in quality of life outcomes and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: results from the dependence in AD in England 2 longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30: 400–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coucill W, Bryan S, Bentham P, Buckley A, Laight A. EQ-5D in patients with dementia: an investigation of inter-rater agreement. Med Care 2001; 39: 760–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shearer J, Green C, Ritchie CW, Zajicek JP. Health state values for use in the economic evaluation of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2012; 29: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pullenayegum EM, Perampaladas K, Gaebel K, Doble B, Xie F. Between-country heterogeneity in EQ-5D-3L scoring algorithms: how much is due to differences in health state selection? Eur J Health Econ 2015; 16: 847–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.