Abstract

Background

antipsychotic drugs are regularly prescribed as first-line treatment for neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia although guidelines clearly prioritise non-pharmacological interventions.

Objective

we investigated a person-centred care approach, which has been successfully evaluated in nursing homes in the UK, and adapted it to German conditions.

Design

a 2-armed 12-month cluster-randomised controlled trial.

Setting

nursing homes in East, North and West Germany.

Methods

all prescribing physicians from both study arms received medication reviews for individual patients and were offered access to 2 h of continuing medical education. Nursing homes in the intervention group received educational interventions on person-centred care and a continuous supervision programme. Primary outcome: proportion of residents receiving at least one antipsychotic prescription after 12 months of follow-up. Secondary outcomes: quality of life, agitated behaviour, falls and fall-related medical attention, a health economics evaluation and a process evaluation.

Results

the study was conducted in 37 nursing homes with n = 1,153 residents (intervention group: n = 493; control group: n = 660). The proportion of residents with at least one antipsychotic medication changed after 12 months from 44.6% to 44.8% in the intervention group and from 39.8 to 33.3% in the control group. After 12 months, the difference in the prevalence was 11.4% between the intervention and control groups (95% confidence interval: 0.9–21.9; P = 0.033); odds ratio: 1.621 (95% confidence interval: 1.038–2.532).

Conclusions

the implementation of a proven person-centred care approach adapted to national conditions did not reduce antipsychotic prescriptions in German nursing homes.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02295462.

Keywords: antipsychotic agents, deprescriptions, person-centred care, nursing homes, dementia, older people

Key points

Approximately 40% of the participating nursing home residents had at least one antipsychotic prescription.

The person-centred care approach did not reduce the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions in German nursing homes.

Barriers for person-centred care were staff and time constraints and difficult cooperation with prescribing physicians.

Introduction

Although there is a decline in the prescription rates of antipsychotics in some long-term care settings [1], a comparison between Western European countries indicates large differences between countries. The prescription rates range from 12 to 59% (pooled percentage 27%). Considerably high rates of antipsychotic prescription for residents with dementia have been identified in Germany, Austria and Spain with pooled percentages from 45 to 51% while lower rates with a range from 19.9 to 48.0% were reported in the UK [2].

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that psychological and environmental approaches should be the first treatment option for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) [3, 4]. Antipsychotic drugs should only be used as last resort and discontinued immediately after symptoms vanish or improve within 3 months [5, 6].

Systematic reviews indicate that training and support for nursing home staff reduce the prescription of antipsychotics in residents with dementia [7–9]. A programme with a person-centred care approach from the UK showed the strongest effect [10]. Based on the person-centred care concept of Kitwood, defining characteristics were: to acknowledge the personhood of each individual in all aspects of care, to personalise care and environment, to interpret behaviour from the viewpoint of the person with dementia, and to prioritise the relationship as much as the care tasks [11]. Additionally, medication reviews were conducted in both study groups. The study lead to a significant reduction of the proportion of residents receiving antipsychotics in the intervention group (23.0%) compared to the control group (42.1%) after 12 months [10].

In Germany, currently 13,600 nursing homes for more than 928,900 residents are available [12]. Nursing homes are defined as long-term care facilities that provide 24-h support from healthcare professionals for people who require assistance with activities of daily living and have identified health needs (physical and/or cognitive impairments) [13]. Local outpatient physicians are responsible for residents’ medical care. In contrast to the UK or other countries, the reduction of antipsychotic prescriptions is not a priority in healthcare policy making in Germany. Antipsychotic drug use is not a nursing home quality indicator and no national prescribing protocol exists.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to adapt the person-centred care intervention by Fossey et al. [10] to German conditions and to investigate whether this approach would result in a clinically relevant reduction in the proportion of residents with antipsychotic prescriptions in German nursing homes [14].

Methods

Study design

A multi-centre, cluster-randomised controlled, pragmatic trial using two parallel groups with 1:1 randomisation (on a cluster level) and 12 months of follow-up was conducted. Detailed information regarding the study protocol has been published elsewhere [14].

Ethical approval was obtained from the appropriate authority in each centre.

Participants

Clusters were nursing homes in the areas of Halle (Saale), Lübeck and Witten, Germany.

All residents within a cluster were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria were:

Temporary stay in respite care; and/or

primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

All residents who moved into a nursing home during the study period were also eligible to participate and were asked for consent (post-randomisation). At regular intervals, telephone calls were made, and written reminders were sent out by study staff to ensure post-randomisation recruitment.

The EPCentCare intervention

The intervention programme was based on the study by Fossey et al. [10]. As optimised usual care, residents with an ongoing antipsychotic prescription received a medication review by experienced physicians specialised in psychotropic drug treatment for older people (blinded to group allocation). Medication reviews were based on residents’ case files and communicated as written reports that included specific recommendations for attending physicians. Since residents are free to choose their local outpatient physicians in Germany, it was necessary to conduct the medication reviews both in the intervention group and in the control group in order to avoid contamination due to the physicians involved. Medication reviews were carried out at baseline and after 3, 6 and 9 months according to national evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [3], the PRISCUS list [5, www.priscus.net] and on the basis of product information documents. All physicians involved in prescribing antipsychotics (i.e. general practitioners, neurologists, psychiatrists and geriatricians) were offered 2 h of continuing medical education at the start of the study. Physicians who did not attend received a brochure on the workshop topics.

The control group received no further intervention.

For nursing homes in the intervention group, selected staff were trained and instructed to work as experts for person-centred care for older people. Based on the study by Fossey et al. [10, 15], the training programme included a 2-day initial workshop on person-centred care and continuous in-house support during the intervention period by a study nurse specialised in dementia and person-centred care. In addition, staff in intervention group nursing homes attended an information session about the study (60 min). Further details about the intervention components have been presented in the open access study protocol [14].

Data collection

Data were collected at five measurement points: baseline assessment (t0) and measurements after 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (t1–t4). Data collection was performed between November 2014 and October 2016.

Primary outcome measure

The proportion of residents with at least one antipsychotic prescription after 12 months, as assessed from routine documentation.

Secondary outcome measures

Residents’ quality of life (QoL) as measured by the German version of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale—QoL-AD [16] at recruitment and t4. Self-rated QoL was assessed if residents had a Dementia Screening Scale—DSS [17] score of four or higher, otherwise proxy assessment was obtained from nursing staff.

Agitated behaviour as assessed with a German version of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory—CMAI [18] (measurement points: recruitment and t4).

Prescriptions of antipsychotics (regular and pro re nata (PRN) medication) during the 12-month study period at all measurement points as well as prescriptions of other psychotropic drugs (regular and PRN medication).

Safety parameters such as falls as well as physical restraints [19] at all measurement points.

Additionally, data for a health economic evaluation and a process evaluation were collected. The aim of the process evaluation was to systematically obtain information on the achieved implementation of the intervention components and the contextual factors that affect implementation, and to track changes in intermediate outcomes like competencies and actions of the participants [20]. Therefore, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods was embraced (e.g. investigators’ documentation, standardised questionnaires and semi-structured interviews).

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation has been described in the study protocol. However, after recruiting 28 clusters, only a mean cluster size of 30 (median, 23) residents could be achieved, which was less than had been planned. A recalculation (August 2015) of the sample size based on a lower mean cluster size resulted in the complete retention of 37 clusters and 1,080 residents overall. Therefore, a further increase in the number of clusters was not necessary, assuming no drop out of any cluster.

Study procedure

The study was implemented in recruiting phases of four nursing homes per study site with a time shift of 2 months between recruiting phases. Concordant study procedures in all three study centres were ensured by an external audit. The auditor was instructed in the study methodology by the coordinator, but was otherwise not involved in the study.

A block-wise balanced randomisation sequence was computer-generated by an external biostatistician and centrally assigned on cluster level.

Statistical analysis

A biostatistician who was not involved in conducting the study and was blinded to the group allocation of the residents and clusters performed a step-wise statistical analysis (see study protocol).

The outcome analysis after 12 months included all active participating residents of the nursing homes at that time.

Results

Thirty-seven nursing homes (clusters) with 1,042 residents were included at baseline: 18 nursing homes with 439 residents in the intervention group and 19 nursing homes with 603 residents in the control group. All clusters completed the study. Over the course of the study, 111 residents were recruited after t0 (i.e. post-randomisation; intervention group: n = 54; control group: n = 57). Overall, 291 residents dropped out early due to death or moving (intervention group: n = 120; control group: n = 171). In total, data from 862 residents were included in the primary analysis (study flow chart: Appendix 1, available at Age and Ageing online).

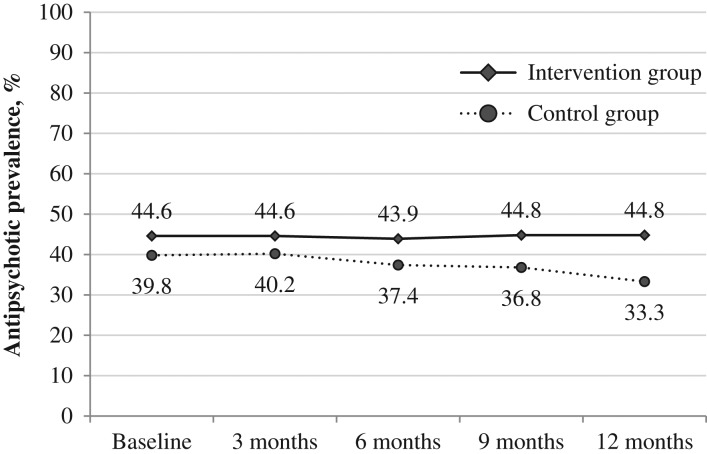

The group-specific baseline characteristics of the residents are shown in Table 1. Groups were well-balanced at baseline. At baseline, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions was higher in the intervention group with a difference of almost 5% (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the clusters are described in Appendix 2, available at Age and Ageing online.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of nursing home residents (n = 1,042)

| Intervention group (n = 439) | Control group (n = 603) | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants per study centre, n | ||

| Halle (Saale) | 185 | 192 |

| Lübeck | 104 | 212 |

| Witten | 150 | 199 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 319 (72.7) | 443 (73.5) |

| Age (years) | 84.0 (±9.5) | 84.1 (±9.1) |

| Mean (standard deviation) | ||

| Minimum–maximum | 45–103 | 40–105 |

| Length of residence (weeks), median (2 miss) | 115.6 | 119.7 |

| Care dependency categorya, n (%) | ||

| None | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) |

| Level 0 | 5 (1.1) | 11 (1.8) |

| Level 1 (considerable) | 152 (34.6) | 188 (31.2) |

| Level 2 (severe) | 186 (42.4) | 255 (42.3) |

| Level 3 (most severe) | 92 (20.9) | 147 (24.4) |

| Residents with at least one antipsychotic drug, % (n) | 44.6 (196) | 39.8 (240) |

| Residents with cognitive impairment | ||

| (DSS > 4)b, n (%) (3 miss) | 253 (58.0) | 324 (53.7) |

| Dementia Screening Scale (DSS)b (3 miss) | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 5.9 (±4.6) | 5.8 (±4.8) |

| Minimum–maximum | 0–14 | 0–14 |

| Residents with agitated behaviour (6 miss) | ||

| (CMAI>25)c, n (%) | 245 (56.5) | 341 (56.6) |

| Agitated behaviour (CMAI)c | ||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 31.4 (±9.9) | 31.4 (±10.3) |

| Minimum–maximum | 25–86 | 25–90 |

| Quality of life (QoL-AD)d, mean (standard deviation) minimum–maximum | ||

| Self-assessment | 33.4 (±5.3) | 34.1 (±5.9) |

| 20–48 | 18–49 | |

| Proxy assessment | 31.1 (±6.8) | 30.7 (±5.9) |

| 13–52 | 13–46 | |

| Living in a dementia-specific unit, n (%) | 81 (18.5) | 67 (11.1) |

| Legal guardian, n (%) (1 miss) | 156 (35.5) | 226 (37.5) |

| Physical restraintse, n (%) (8 miss) | 61 (14.0) | 94 (15.7) |

| ≥1 fall in preceding 4 weeks, n (%) (1 miss) | 45 (10.3) | 74 (12.3) |

aResidents’ need for care was assessed by the medical service of the German social care insurance; Need for care in performing activities of daily living and household tasks was defined as Level 0: <90 min/day, Level 1: at least 90 min/day, Level 2: at least 3 h/day, Level 3: at least 4 h/day.

bDSS: Dementia Screening Scale (total score ranges from 0 to 14; higher scores indicate more severe cognitive impairments).

cCMAI: Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (total score ranges from 25 to 175, higher scores indicate higher frequencies of manifestations).

dQoL-AD: Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease scale (total score ranges from 13 to 52, higher scores indicate better QoL); valid measurements included intervention group: n = 433 (self: 147, proxy: 286); control group: n = 603 (self: 229, proxy: 374).

eBedrails, fixed tables, belts in bed or chair, other physical restraints.

Figure 1.

Antipsychotic prevalence throughout the study.

The characteristics of the residents who were recruited post-randomisation (n = 111) are shown in Appendix 3, available at Age and Ageing online. Residents who were recruited post-randomisation to the intervention group were more severely cognitively impaired and had a higher care dependency than those who were recruited to the control group. As shown in Appendix 4, available at Age and Ageing online, residents who were recruited post-randomisation differed in terms of the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions between the intervention group and control group.

During the course of the study, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions in the entire sample decreased in the control group and remained stable in the intervention group (Figure 1). After 12 months (Table 2), the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions was significantly lower in the control group than in the intervention group (prevalence difference, 11.4%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.9–21.9).

Table 2.

Summary of analyses for outcome measures 12-month follow-up

| Outcome measures 12-month follow-up | Intervention group | Control group | Effectiveness parameter | 95% Confidence interval | ICC | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Antipsychotic drugs (at least 1), % (n) | 44.8 (167) | 33.3 (163) | Odds ratio 1.621 | (1.038 to 2.532) | 0.057 | 0.033 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Quality of life (QoL-AD)a | ||||||

| Self-assessment, mean (n) | 33.1 (120) | 34.0 (170) | Mean difference -0.9 | (−3.0 to 1.1) | 0.094 | 0.365 |

| Proxy assessment, mean (n) | 30.2 (252) | 31.4 (317) | Mean difference -1.2 | (−3.3 to 0.8) | 0.142 | 0.227 |

| Agitated behaviour (CMAI>25)b, % (n) | 53.9 (373) | 43.0 (488) | Odds ratio 1.547 | (0.863 to 2.772) | 0.131 | 0.141 |

| Psychotropic drugsc (at least 1), % (n) | 55.2 (373) | 53.0 (489) | Odds ratio 1.095 | (0.807 to 1.487) | 0.010 | 0.559 |

| Falls (at least 1), % (n) | 22.0 (373) | 21.5 (488) | Odds ratio 1.028 | (0.679 to 1.556) | 0.022 | 0.897 |

| Physical restraintsd, % (n) | 11.3 (373) | 8.2 (489) | Odds ratio 1.424 | (0.529 to 3.834) | 0.133 | 0.480 |

aQoL-AD: Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease scale (total score ranges from 13 to 52, higher scores indicate better QoL); effect estimation by linear mixed model.

bCMAI: Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (total score ranges from 25 to 175, higher scores indicate higher frequencies of manifestations).

cAntidepressants, anxiolytics and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

dBedrails, fixed tables, belts in bed or chair, other physical restraints.

ICC=intra-class correlation coefficient.

After excluding residents who were recruited post-randomisation from the analysis, a reduction in antipsychotic prescription rates could be observed in both groups. Intervention group: 44.6–41.3%; control group: 39.8–33.9%, with a non-significant difference between the two groups (prevalence difference, 7.4%; 95% CI: −2.9 to 17.7; P = 0.156).

The variability in the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions between the nursing homes was considerable (see Appendix 4, available at Age and Ageing online). At baseline, the prevalence ranged from 17.6 to 96.3% (mean prevalence: 42.6%), after 12 months from 0.0 to 70.0% (mean prevalence: 38.1%).

Further data on prescription of antipsychotics are summarised in Appendix 4, available at Age and Ageing online.

Results for the secondary outcomes after 12 months showed no statistically significant differences between the study groups (Table 2).

The process evaluation revealed that the study intervention components were offered as planned, but the degree of implementation varied across intervention components and nursing homes. The medication reviews and the initial person-centred care workshops were carried out with high fidelity. In contrast, the continuing medical education provided for physicians was attended by very few physicians. Similarly, in some nursing homes, the support programme for the experts for person-centred care for older people could only be implemented to a limited extent due to restricted time capacities of them. Further barriers found were a lack of willingness of colleagues of the experts for person-centred care for older people to support them, and difficulties regarding cooperation with the physicians involved. Details of the process evaluation (implementation and acceptability of the study intervention components and effects on intermediate outcomes) are shown in Appendix 5, available at Age and Ageing online.

We did not calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio since the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions declined in the control group instead of in the intervention group. When the time of lecturers, experts for person-centred care for older people and nurses was considered, intervention costs added up to 52,518 Euro (further details: Appendix 6, available at Age and Ageing online).

Discussion

The implementation of a complex intervention programme with a person-centred care approach, evaluated as successful in the UK and adapted to the German healthcare system, did not lead to a reduction in antipsychotic prescriptions in the intervention group; in the control group, however, a reduction was found. The primary analysis revealed a significantly lower prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions in the control group than in the intervention group. It should be noted that already at baseline, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions in the control group was 4.8% lower than that in the intervention group.

Systematic reviews have shown that psychosocial interventions can lead to a reduction in antipsychotic prescriptions in residents with dementia [7, 9], and person-centred care interventions can reduce BPSD [21]. Although the person-centred care approach has been evaluated as successful [10] and widely implemented in the UK [22], the effects could not be replicated in German nursing homes. An adaptation of the intervention to the German healthcare system required several changes compared to the study by Fossey et al. [10]. The workshop and support programme for the experts for person-centred care for older people were based on the original training manual [15] and corresponding material [23], but instead of a personal exchange between the medication reviewers and attending physicians, only a written recommendation was possible. Furthermore, unlike the list system of primary care that is predominant in the UK, in Germany, the patient is free to choose his/her primary care physician. Consequently, there is a large number of physicians treating residents in a single nursing home thus complicating nurse–physician communication. The importance of commitment of attending physicians to reduce antipsychotic prescriptions was also emphasised in a recent study [24].

The results of the process evaluation suggest that the person-centred care approach was not implemented to the desired extent. In some nursing homes, contextual factors such as staff and time constraints as well as working conditions impeded the experts for person-centred care for older people to fulfil their disseminator role consistently. Therefore, the intensity of the intervention, as implemented in the UK [10], was not achieved throughout all nursing homes. Concordant with the normalisation process theory [25], more support from the nursing home management could have encouraged change processes. However, it seems essential to increase skilled staff in German nursing homes in order to be able to adequately implement person-centred care.

The subgroup analyses showed that residents who were recruited post-randomisation particularly contributed to the difference in the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions. A large turn-over of residents was assumed; therefore, consecutive post-randomisation recruitment was planned. However, the recruitment rate from t1 onwards was lower than expected. Despite clear guidelines for the nursing homes, recruitment rates varied widely between clusters and over time. It is likely that post-randomisation recruitment was influenced by staff after t0. Residents in the intervention group had a higher level of care, increased cognitive impairments and higher number of antipsychotic prescriptions than those in the control group. Thus, a post-randomisation recruitment bias, as reported by Hahn et al. [26] is likely. In the intervention group, residents with higher needs of care may have been recruited preferentially to receive medication reviews. As medication reviews were carried out in both groups to avoid contamination effects, no definite conclusion can be drawn about the efficacy of these reviews. The data suggest a small trend towards a reduction of the number of antipsychotic prescriptions in both groups, which might be an indication to recent findings on the effectiveness of medication reviews [27].

Additionally, the heterogeneity in the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions between the nursing homes is a limitation of the study. Sensitivity analyses using mixed models did not change the main results (data not shown). The participating institutions are representative for nursing homes in Germany. Reasons for the detected differences are unclear, but the culture of care as reflected in the attitudes and beliefs of nursing staff and a lack of cooperation with physicians, may have determined the observed variation.

In some European countries, like Norway and the UK, governmental and clinical initiatives led to major reductions in antipsychotic drug use for people with dementia in the last decade [24, 28]. Whether strict official policy making and clinical initiatives like those, would lead to a more evidence-based culture of minimum use of antipsychotic drugs remains to be investigated in Germany.

Conclusion

Overall, ~40% of the nursing home residents who took part in the EPCentCare study had at least one antipsychotic prescription. The person-centred care approach had no additional effect on the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions compared to medication review alone under the given working conditions in German nursing homes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Prof. Dr Med. Horst Christian Vollmar who contributed to the concept of continuing medical education. We thank Charalabos-Markos Dintsios, PhD and Markus Vomhof for their economical advice. We thank Prof. Dr Med. Hans Jürgen Heppner, Dr med. Lutz Michael Drach [†], Dr med. Johannes Rosenboom and Dr med. Hauke Iven for performing the medication reviews in Witten/Herdecke and Lübeck.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: Ursula Wolf accepted fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer after the end of the trial in 2018 for oral presentations on side effects of potentially inappropriate medications in older people. The other authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Declaration of Sources of Funding: This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF grants 01GY1335A, 01GY1335B and 01GY1335C). The funding institution did not interfere in any part of the study.

References

- 1. Kirkham J, Sherman C, Velkers C et al. Antipsychotic use in dementia. Can J Psychiatry 2017; 62: 170–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Janus SI, van Manen JG, IJzerman MJ, Zuidema SU. Drug prescriptions in Western European nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr 2016; 28: 1775–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN). In: Zusammenarbeit mit der Deutschen Alzheimer Gesellschaft e.V.—Selbsthilfe Demenz. S3-Leitlinie ‘Demenzen’. AWMF-Register-Nr. 038-013. 2016. [17.05.2018]. Available at http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/038-013.html.

- 4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. 2016.

- 5. Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107: 543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Leeuwen E, Petrovic M, van Driel ML et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of long-term antipsychotic drug use for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 3: CD007726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birkenhager-Gillesse EG, Kollen BJ, Achterberg WP, Boersma F, Jongman L, Zuidema SU. Effects of psychosocial interventions for behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia on the prescription of psychotropic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018; 19: 276.e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fossey J, Masson S, Stafford J, Lawrence V, Corbett A, Ballard C. The disconnect between evidence and practice: a systematic review of person-centred interventions and training manuals for care home staff working with people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 29: 797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richter T, Meyer G, Möhler R, Köpke S. Psychosocial interventions for reducing antipsychotic medication in care home residents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD008634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E et al. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. Br Med J 2006; 332: 756–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistisches Bundesamt Pflegestatistik 2015. Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung Deutschlandergebnisse. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D et al. An international definition for ‘nursing home’. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015; 16: 181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richter C, Berg A, Fleischer S et al. Effect of person-centred care on antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes (EPCentCare): study protocol for a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2015; 10: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fossey J, James I. Evidence-Based Approaches for Improving Dementia Care in Care Homes. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Mental Health Aging 1999; 5: 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Köhler L, Weyerer S, Schäufele M. Proxy screening tools improve the recognition of dementia in old-age homes: results of a validation study. Age Ageing 2007; 36: 549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Rosenthal AS. A description of agitation in a nursing home. J Gerontol 1989; 44: M77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Gerlach A et al. Effect of a guideline-based multicomponent intervention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 2012; 307: 2177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J 2015; 350: h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim SK, Park M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging 2017; 12: 381–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brooker DJ, Latham I, Evans SC et al. FITS into practice: translating research into practice in reducing the use of anti-psychotic medication for people with dementia living in care homes. Aging Ment Health 2016; 20: 709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alzheimer’s Society Optimising Treatment and Care for People with Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. A Best Practice Guide for Health and Social Care Professionals. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ballard C, Corbett A, Orrell M et al. Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2018; 15: e1002500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009; 43: 535–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahn S, Puffer S, Torgerson DJ, Watson J. Methodological bias in cluster randomised trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alldred DP, Kennedy MC, Hughes C, Chen TF, Miller P. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 2: CD009095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Testad I, Mekki TE, Forland O et al. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)—training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 31: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.