Abstract

Background

The aim was to investigate the co-morbidity profile of people with dementia and examine the associations between severity of co-morbidity, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and quality of life (QoL).

Methods

The improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life (IDEAL) cohort consisted of 1,547 people diagnosed with dementia who provided information on the number and type of co-morbid conditions. Participants also provided ratings of their health-related and dementia-specific QoL.

Results

The majority of the sample were living with more than one chronic condition. Hypertension was commonly reported and frequently combined with connective tissue disease, diabetes and depression. The number of co-morbid conditions was associated with low QoL scores, and those with severe co-morbidity (≥5 conditions) showed the greatest impact on their well-being.

Conclusions

Co-morbidity is an important risk factor for poor QoL and health status in people with dementia. Greater recognition of the nature and impact of co-morbidity is needed to inform support and interventions for people with dementia and a multidisciplinary approach to care provision is recommended.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s, multimorbidities, depression, older people

Key points

The majority of people with dementia were living with one or two chronic health conditions, and hypertension was the most frequent co-morbid condition.

Multiple health conditions have important consequences for the quality of life (QoL) and well-being of the individual.

This study highlights the need for better care planning and the organisation of care provision to deal with multiple conditions in an integrated way.

Living with dementia poses many challenges for people with dementia and for those who care for them. This may be coupled with other health problems as the accumulation of changes associated with ageing can lead to the accrual of illnesses and disabilities [1]. With the increased prevalence of individual health conditions associated with ageing [2], there is growing interest in the co-occurrence of medical conditions and the implications for the individual. Multimorbidity and co-morbidity are used interchangeably to describe the presence of co-occurring diseases but definitions vary across studies. Multimorbidity is the co-occurrence of two or more diseases or active health conditions that may or may not be linked by a causal relationship or with no consistent dominant index disorder. Co-morbidity is the term given to the presence of conditions existing concurrently with a condition considered as the primary or index disease [1] and this study will focus on the presence of conditions in addition to dementia as the index condition. Co-morbidities significantly associated with dementia include physical health conditions such as congestive cerebrovascular disease, and cardiac arrhythmia [3], hypertension and diabetes [4], and depression [5].

People with dementia are more likely to have five or more health conditions and more prescription usage than those without dementia [6], and co-morbidity ranging from two to eight conditions has been reported [7]. Examination of the medical records in England showed that 92% of people with dementia had a formal diagnosis of at least one other disease, and 53% were considered to have co-morbidity with three or more conditions [2]. Similarly, 61% of people with Alzheimer’s disease across various care settings had three or more conditions [8]. Co-morbidity rates were the same for people with dementia compared with those without dementia in a primary care [7], but for care home residents, rates were higher in people with dementia compared with older care residents without dementia [9]. There is growing interest not only in the number of co-morbid conditions but also in the combinations or array of conditions referred to as ‘morbidotypes’ [10].

Co-morbidity can influence a range of health outcomes such as mortality [11] and disability [12]. Multimorbidity is negatively associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [9, 13], and certain disease combinations, such as diabetes and coronary disorders, impact more on HRQoL than others [14]. Higher co-morbidity in people with dementia is negatively associated with ratings of disease-specific QoL [15]. Generally there is a negative association between co-morbidity and QoL but the results are not conclusive, with variable findings related to QoL and HRQoL [16], and few studies examining both perceptions of health-related QoL and well-being.

People with dementia are living with co-morbidity, and greater recognition of the extent and impact of this burden of disease is essential for the identification of interventions to help maintain independence and improve QOL [17]. Co-morbidity poses significant challenges for care provision, and greater coordination of care planning across conditions is needed [4, 18]. The aim of this study is to investigate the co-morbidity profile of people with dementia and to examine the associations between severity of co-morbidity, HRQoL and QoL using a large community-based cohort of people with dementia.

Method

Sample

Participants were drawn from the baseline wave of the ‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life’ (IDEAL) longitudinal cohort study recruited across Great Britain [19]. Inclusion criteria included a clinical diagnosis of dementia and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥15 [20]. Interviews were conducted in participant homes. Analysis is based on V2 of the IDEAL baseline (T1) dataset.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was secured for all participants. Ethics approval was granted by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 (reference 13/WA/0405) and the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Bangor University (reference 2014–11684). The IDEAL study is registered with UKCRN, registration number 16593.

Measures

Information on the age profile, diagnostic subtypes and educational level of the cohort was included in analyses.

Co-morbidity

A record of the presence or absence of 23 chronic conditions was collected using the Charlson co-morbidity index (CCI) [21], administered through a joint interview with the person with dementia and carer where available. The CCI included diseases selected on the basis of their association with mortality and this version of the CCI includes depression, hypertension, ulcers and use of warfarin [21]. A count of the diseases within the index is used as a measure of co-morbidity, and as we were interested in the impact of diseases in addition to our index condition dementia was not counted in the analysis. Co-morbidity was categorised into four levels of severity: no co-morbidity, mild (1–2 conditions), moderate (3–4 conditions) and severe (≥5 conditions).

Health-related quality of life

Participants rated their HRQoL using the two parts of the EQ-5D-3L [22]:

The EQ-5D-3L descriptive system has five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The EQ-5D dimensions were dichotomised into ‘no problems’ and ‘moderate/severe problems’ for logistic regression analyses.

The EQ-5D visual analogue scale (EQ-5D VAS) provides a self-rating of health on a vertical visual analogue scale from 0 = ‘worst imaginable health state’ to 100 = ‘best imaginable health state’. This is used as a quantitative measure of HRQoL.

Quality of life

The QoL in Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD) scale was developed specifically for people with dementia and focuses on QoL domains important in cognitively impaired older people. Participants rate aspects of their current situation such as mood, memory and make a global assessment of QoL as a whole [23]. Scale scores range from 13 to 52, with higher scores representing greater QoL.

Statistical analyses

The analysis first investigated the frequencies and prevalence of different conditions and their combinations. Linear regression was conducted to investigate the associations between severity of co-morbidity and both HRQoL and QoL-AD. The associations between severity of co-morbidity and the five individual dimensions of the EQ-5D were examined using logistic regression. The models were adjusted for participants’ sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, education and dementia subtype.

Results

The IDEAL cohort consisted of 1,547 people diagnosed with dementia at baseline; 56.3% were males. The mean MMSE score was 24.15 (s.d. 3.46; range 14–30). The mean age of the people with dementia was 76.4 (s.d. 8.5). The majority of the sample had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (55.5%). Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample and level of co-morbid conditions

| Characteristics | N (%) | Co-morbid conditions, N (%), missing (n = 85) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–2 | 3–4 | ≥5 | ||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| N | 1,547 | 365 (25) | 757 (52) | 259 (17) | 81 (5) |

| Age groups | |||||

| <65 | 136 (8.8) | 48 (13.2) | 60 (7.9) | 14 (5.4) | 10 (12.3) |

| 65–69 | 178 (11.5) | 44 (12.0) | 95 (12.5) | 23 (8.8) | 10 (12.3) |

| 70–74 | 260 (16.8) | 70 (19.2) | 122 (16.2) | 39 (15.0) | 13 (16.1) |

| 75–79 | 370 (23.9) | 83 (22.7) | 184 (24.3) | 62 (23.9) | 21 (25.9) |

| 80+ | 603 (38.9) | 120 (32.9) | 296 (39.1) | 122 (46.7) | 27 (33.3) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 872 (56.3) | 198 (54.2) | 430 (56.8) | 143 (55.2) | 54 (66.6) |

| Female | 675 (43.6) | 167 (45.7) | 327 (43.2) | 116 (44.7) | 27 (33.3) |

| Dementia diagnosis | |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 858 (55.5) | 246 (67.4) | 435 (57.5) | 108 (41.7) | 34 (41.9) |

| Vascular dementia | 171 (11.0) | 21 (5.7) | 64 (8.5) | 56 (21.6) | 18 (22.2) |

| Mixed (Alzheimer’s and vascular) | 326 (21.0) | 45 (12.2) | 161 (21.3) | 73 (28.2) | 25 (30.8) |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 54 (3.5) | 20 (5.5) | 26 (3.4) | 6 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia | 44 (2.8) | 8 (2.2) | 25 (3.3) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (2.5) |

| Lewy body dementia | 53 (3.4) | 15 (4.1) | 26 (3.4) | 7 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) |

| Unspecified/Other | 41 (2.7) | 10 (2.7) | 20 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Quality of life measures | |||||

| QoL-AD total score, mean (SD) | 36.7 (5.9) | 38.6 (5.7) | 37.1 (5.6) | 34.5 (5.8) | 32.7 (5.4) |

| EQ-5D VAS, mean (SD) | 71.9 (18.6) | 77.7 (16.7) | 72.5 (17.8) | 66.5 (19.3) | 59.9 (21.5) |

| EQ-5D problems, N (%) | |||||

| Mobility | |||||

| None | 897 (58.1) | 280 (77.1) | 458 (60.6) | 101 (39.0) | 14 (17.3) |

| Moderate/Severe | 646 (41.8) | 83 (22.8) | 297 (39.3) | 158 (61.0) | 67 (82.7) |

| Self-care | |||||

| None | 1,209 (82.8) | 331 (90.9) | 643 (84.2) | 187 (72.0) | 48 (59.2) |

| Moderate/Severe | 252 (17.2) | 33 (9.1) | 114 (15.6) | 72 (27.8) | 33 (40.7) |

| Usual activities | |||||

| None | 1,018 (66.1) | 277 (76.3) | 532 (70.6) | 140 (54.2) | 27 (33.3) |

| Moderate/Severe | 522 (33.9) | 86 (23.7) | 221 (29.3) | 118 (45.7) | 54 (66.6) |

| Pain/Discomfort | |||||

| None | 924 (59.8) | 276 (75.8) | 456 (60.3) | 120 (46.5) | 20 (24.7) |

| Moderate/Severe | 620 (40.2) | 88 (24.2) | 300 (39.7) | 138 (53.4) | 61 (75.3) |

| Anxiety/Depression | |||||

| None | 1,014 (65.8) | 260 (71.4) | 518 (68.7) | 144 (56.0) | 38 (46.9) |

| Moderate/Severe | 526 (34.2) | 104 (28.6) | 236 (31.3) | 113 (43.9) | 43 (53.1) |

Note: QoL-AD = quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease; VAS = visual analogue scale.

The average HRQoL score was 71.93 (s.d. 18.61), with an average QoL-AD score of 36.77 (s.d. 5.92). Information on the EQ-5D domains is shown in Table 1, with moderate or severe difficulties reported with mobility (41.8%), self-care (17.2%), performance of usual activities (34%), pain (40.2%) and anxiety or depression (34%).

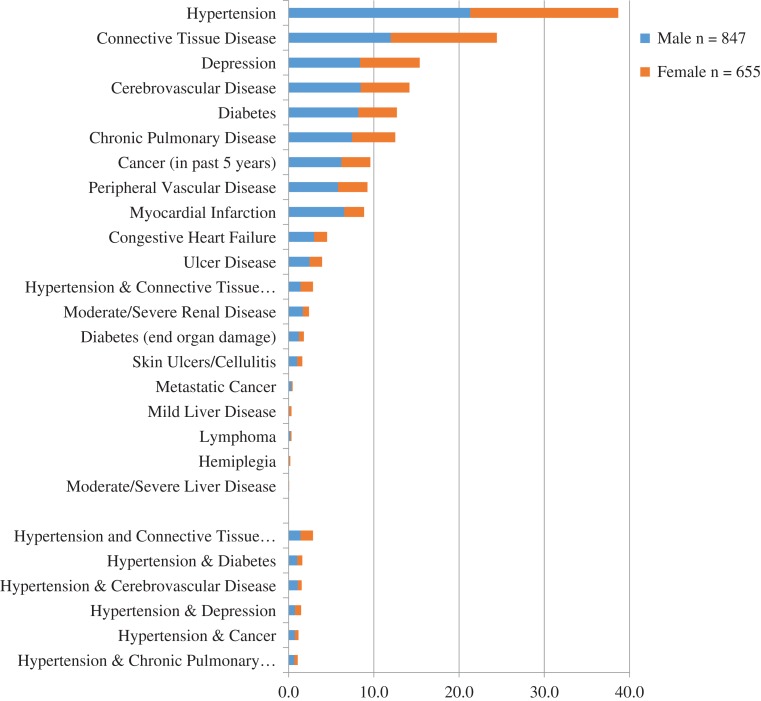

Prevalence and combinations of co-morbid conditions

The median number of co-morbid conditions reported was 1, with a range from 0 to 9. The prevalence of the individual co-morbid conditions included in the CCI for the whole sample and by gender is shown in Figure 1. The five most frequent conditions across the cohort were: hypertension (38.7%); connective tissue disease (24.5%); depression (15.4%); diabetes (12.7%); and chronic pulmonary disease (12.5%). This pattern of prevalence was similar in both males and females with the exception of the higher prevalence of myocardial infarction in men (11.6%) vs. 5.3% in women.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of co-morbid conditions associated with dementia

Over 300 combinations of co-morbid conditions were found but most combinations had low frequencies (N < 10). The most frequent two-way co-morbidities were hypertension with connective tissue disease (N = 43), hypertension and diabetes (N = 24), and hypertension and depression (N = 22). Three-way co-morbid combinations follow a similar pattern with hypertension present in all three of the top combinations: hypertension, connective disease and diabetes (N = 12); hypertension, cardiovascular disease and connective tissue disease (N = 8); and myocardial infarction, hypertension and connective tissue disease (N = 7).

Table 1 reports the number of co-morbid conditions by sociodemographic factors. In total, 25% of the sample did not report the presence of any co-morbid condition. The majority (52%) had mild (1–2 conditions) co-morbidity and only 5% had severe co-morbidity (>5 conditions). The distribution was similar across gender and age groups but varied across dementia subtypes. The percentage of vascular dementia and mixed AD and VD subtypes increased with the severity of co-morbid conditions.

Table 2 reports the associations between level of co-morbidity and ratings on the QoL-AD and the EQ-5D. There was a negative association between severity of co-morbid conditions and both QoL-AD and HRQoL scores. Compared to those with no chronic conditions, participants with severe co-morbidity (≥5 conditions) had lower QoL-AD by 6 points (−5.84; 95% CI: −7.27, −4.41) and lower HRQoL scores by 18 points (−17.82; 95% CI: −22.23, −13.42). After adjusting for age, sex, dementia subtypes and education, the adjusted estimates were −5.07 (95% CI: −6.53, −3.62) for QoL-AD and −15.85 (95% CI: −20.36, −11.34) for HRQoL.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between co-morbidity, health-rated quality of life (EQ-5D) and quality of life (QoL-AD) and the five EQ-5D domains

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model* | |

|---|---|---|

| Coeff. (95% CI) | Coeff. (95% CI) | |

| QoL-AD | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | −1.45 (−2.19, −0.70) | −1.35 (−2.09, −0.62) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | −4.16 (−5.13, −3.20) | −4.07 (−5.05, −3.09) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | −5.84 (−7.27, −4.41) | −5.07 (−6.53, −3.62) |

| EQ-5D VAS | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | −5.15 (−7.43, −2.87) | −4.85 (−7.13, −2.57) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | −11.14 (−14.04, −8.24) | −10.58 (−13.53, −7.63) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | −17.82 (−22.23, −13.42) | −15.85 (−20.36, −11.34) |

| EQ-5D domains | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D mobility | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | 2.18 (1.64, 2.90) | 1.98 (1.46, 2.68) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | 5.27 (3.71, 7.48) | 4.44 (3.06, 6.45) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | 16.14 (8.63, 30.18) | 14.64 (7.54, 28.41) |

| EQ-5D self-care | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | 1.77 (1.18, 2.67) | 1.85 (1.20, 2.87) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | 3.86 (2.46, 6.05) | 4.50 (2.75, 7.37) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | 6.89 (3.90, 12.18) | 6.46 (3.44, 12.13) |

| EQ-5D usual activities | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | 1.33 (1.00, 1.78) | 1.24 (0.90, 1.69) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | 2.71 (1.92, 3.83) | 2.44 (1.68, 3.55) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | 6.44 (3.82, 10.85) | 5.77 (3.28, 10.15) |

| EQ-5D Pain/discomfort | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | 2.06 (1.55, 2.73) | 1.97 (1.47, 2.64) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | 3.60 (2.56, 5.08) | 3.43 (2.38, 4.92) |

| >5 Severe vs. none | 9.56 (5.46, 16.73) | 8.51 (4.72, 15.36) |

| EQ-5D Anxiety/Depression | ||

| 1–2 Mild vs. none | 1.13 (0.86, 1.49) | 1.18 (0.89, 1.58) |

| 3–4 Moderate vs. none | 1.96 (1.40, 2.74) | 2.17 (1.52, 3.10) |

| ≥5 Severe vs. none | 2.83 (1.72, 4.62) | 2.81 (1.66, 4.74) |

*Adjusted for age group, sex, dementia subtypes and education.

Note: QoL-AD = quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease; VAS = visual analogue scale.

For the five EQ5D domains severe co-morbidity was also associated with higher odds of moderate/severe problems in mobility (OR = 14.64; 95% CI:7.54, 28.41), self-care issues (OR = 6.46; 95% CI: 3.44, 12.13), impairment in usual activities (OR = 5.77; 95% CI: 3.28, 10.15), pain/discomfort (OR = 8.51; 95% CI: 4.72, 15.36) and anxiety/depression (OR = 2.81; 95% CI: 1.66, 4.74) after adjustment for sociodemographic factors (Table 2).

Discussion

Using dementia as the index disease, this study examined the co-occurrence and combinations of conditions in people with dementia living in the community. The majority were living with one or two chronic health conditions, with 5% reporting more than five co-morbidities. Hypertension was the most frequent co-morbid condition. The severity of co-morbid conditions was associated with lower both HRQoL and dementia-specific QoL. People with severe co-morbid conditions had higher odds of problems in mobility, self-care, managing usual activities, pain and mood. The IDEAL cohort had similar rates of co-morbidity as those previously reported for people living with dementia [6], with 74% of people reporting more than one condition. Prevalence rates for co-morbidity vary across living situation and stages of dementia [7]. Co-morbidities linked with dementia identified through medical records report than 92% live with more than one condition [2]. Differences in prevalence rates may be attributed to the broader range of conditions encompassed in reviews of medical records than those collected by self-report [3].

Co-morbidities most prevalent in the dementia cohort were hypertension, connective tissue disease, depression, diabetes and chronic pulmonary disease. Combinations of conditions included hypertension with connective tissue disease, diabetes and depression. Hypertension prevalence rates are high in this age group [24]. For the main co-morbidities we identified there are known associations between both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia and hypertension [25], and diabetes is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia [26]. Depression in mid- to late life has been linked with an increased risk of dementia [27], and the prevalence of depression in people with Alzheimer’s disease is high [28].

People with multiple chronic conditions were at greater risk of health problems in mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression compared with people living with dementia only. The severity of co-morbid conditions was negatively associated with global ratings of HRQoL, consistent with previous studies [9, 13], and with disease-specific assessment of QoL [15]. Previous research has considered the impact of co-morbidity in one QoL domain [9] and this study provides additional evidence that co-morbidity may have a substantial impact on a person’s subjective perception of ill health and perceptions of well-being related to dementia.

There are some limitations in the measurement of co-morbidity within the study. Reliance on patient-reported co-morbidity may have led to the under-reporting of co-morbid conditions and confirmation with medical records is recommended for future studies [29]. The CCI mainly considers physical health conditions, and depression is the only mental health condition included. Depression can have an independent negative impact on QOL as well as amplifying the impact of physical conditions on perceived QOL [5]. The CCI does not encompass other physical changes or challenges associated with ageing (e.g. falls or frailty) that may also impact on QoL. There is growing recognition of the importance of considering frailty in combination with co-morbidity [30], and this has also extended to clinical guidelines [18]. A longitudinal perspective on the impact of co-morbidity as dementia progresses would be useful, as the co-morbidity may differ across stages of dementia and new chronic conditions may arise.

Co-morbidity in dementia may have serious implications for well-being, and information on the nature of co-morbidity is needed to plan adequate support and interventions [17]. The issue of co-morbidity poses significant challenges for care provision [4]. Dementia may impact on decision-making and on the self-management of chronic conditions [7]. There has been a move to identify groups at whom interventions to deal with co-morbidity should be targeted; those at most risk are people who find it difficult to manage everyday activities, those who are frail, and those who receive care from multiple sources [18].

This study suggests that co-morbidity is an important risk factor for poor health and global well-being in people with dementia. It is evident that people with dementia are experiencing the impact of living with multiple diseases and there is need for greater support and intervention in care provision and planning. Care providers often focus on individual conditions and this study highlights the need for better care planning and the organisation of care provision to deal with multiple conditions in an integrated way. The presence of multiple conditions is likely to increase the burden on carers who support people with dementia and the implications of this additional responsibility for carers should also be considered.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the following research networks: NIHR Dementias and neurodegeneration specialty (DeNDRoN) in England, the Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network (SDCRN) and Health and Care Research Wales.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

The IDEAL study is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK) and the National Institute for Health Research (UK) through grant ES/L001853/2 ‘Improving the experience of dementia and enhancing active life: living well with dementia’ (Investigators: L. Clare, I.R. Jones, C. Victor, J.V. Hindle, R.W. Jones, M. Knapp, M. D. Kopelman, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F. Matthews, R.G. Morris, S.M. Nelis, J. Pickett, C. Quinn, J. Rusted, J. Thom).

Data access

The research materials supporting this publication will be made accessible through the UK Data Archive (http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/) in 2019.

References

- 1. Yancik R, Ershler W, Satariano W, Hazzard W, Cohen HJ, Ferrucci L. Report of the National Institute on Aging Task Force on Comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007; 62: 275–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Melzer D, Delgado J, Winder R, Masoli J, Richards S, Ble A. The Age UK Almanac of Disease Profiles in Later Life. UK: Ageing Research Group, University of Exeter, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poblador-Plou B, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Marta-Moreno J et al. Comorbidity of dementia: a cross-sectional study of primary care older patients. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyers BS. Depression and dementia: comorbidities, identification, and treatment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1998; 11: 201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clague F, Mercer SW, McLean G, Reynish E, Guthrie B. Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Age Ageing 2017; 46: 33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, Marin D, Neumann PJ. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002; 57: M173–M7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martín-García S, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Martínez-López I, Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ. Comorbidity, health status, and quality of life in institutionalized older people with and without dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25: 1077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA, Schwartz JB. Patterns of chronic co-morbid medical conditions in older residents of U.S. nursing homes: differences between the sexes and across the agespan. J Nutr Health Aging 2014; 18: 429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Incalzi RA, Capparella O, Gemma A et al. The interaction between age and comorbidity contributes to predicting the mortality of geriatric patients in the acute‐care hospital. J Intern Med 1997; 242: 291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mulrow CD, Gerety MB, Cornell JE, Lawrence VA, Kanten DN. The relationship between disease and function and perceived health in very frail elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brettschneider C, Leicht H, Bickel H et al. Relative impact of multimorbid chronic conditions on health-related quality of life: results from the MultiCare Cohort Study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunger M, Thorand B, Schunk M et al. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life in the older population: results from the German KORA-age study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bárrios H, Verdelho A, Narciso S, Gonçalves-Pereira M, Logsdon R, de Mendonça A. Quality of life in patients with cognitive impairment: validation of the quality of life-Alzheimer’s disease scale in Portugal. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25: 1085–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Ntetu AL, Maltais D. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004; 2: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, Wang HX, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Patterns of chronic multimorbidity in the elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57: 225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NICE Multimorbidity Clinical Assessment and Management. CG56. 2016.

- 19. Clare L, Nelis SM, Quinn C et al. Improving the experience of dementia and enhancing active life—living well with dementia: study protocol for the IDEAL study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014; 12: 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12: 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson Comorbidity Index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 1234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The EuroQol Group EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging 1999; 5: 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joffres M, Falaschetti E, Gillespie C et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in national surveys from England, the USA and Canada, and correlation with stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e003423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Freitag MH, Peila R, Masaki K et al. Midlife pulse pressure and incidence of dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Stroke 2006; 37: 33–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leibson CL, Rocca WA, Hanson V et al. Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145: 301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Byers AL, McCormick M, Schaefer C, Whitmer RA. Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: differential effects for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strober LB, Arnett PA. Assessment of depression in three medically ill, elderly populations: Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke. Clin Neuropsychol 2009; 23: 205–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerritsen AA, Bakker C, Verhey FR, de Vugt ME, Melis RJ, Koopmans RT. Prevalence of comorbidity in patients with young-onset Alzheimer disease compared with late-onset: a comparative cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016; 17: 318–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yarnall AJ, Sayer AA, Clegg A, Rockwood K, Parker S, Hindle JV. New horizons in multimorbidity in older adults. Age Ageing 2017; 46: 882–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]