Abstract

Aim

To compare the associations between concomitant liraglutide use versus no liraglutide use and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all‐cause mortality among patients receiving basal insulin (either insulin degludec [degludec] or insulin glargine 100 units/mL [glargine U100]) in the Trial Comparing Cardiovascular Safety of Insulin Degludec versus Insulin Glargine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes at High Risk of Cardiovascular Events (DEVOTE).

Materials and Methods

Patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk were randomized 1:1 to degludec or glargine U100. Hazard ratios for MACE/mortality were calculated using a Cox regression model adjusted for treatment and time‐varying liraglutide use at any time during the trial, without interaction. Sensitivity analyses were adjusted for baseline covariates including, but not limited to, age, sex, smoking and prior cardiovascular disease.

Results

At baseline, 436/7637 (5.7%) patients were treated with liraglutide; after baseline, 187/7637 (2.4%) started and 210/7637 (2.7%) stopped liraglutide. Mean liraglutide exposure from randomization was 530.2 days. Liraglutide use versus no liraglutide use was associated with significantly lower hazard rates for MACE [0.62 (0.41; 0.92)95%CI] and all‐cause mortality [0.50 (0.29; 0.88)95%CI]. There was no significant difference in the rate of severe hypoglycaemia with versus without liraglutide use. Multiple sensitivity analyses yielded similar results.

Conclusions

Use of liraglutide was associated with significantly lower risk of MACE and death in patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk using basal insulin.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, hypoglycaemia, insulin therapy, liraglutide, randomized trial, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular complications are the leading causes of diabetes‐related morbidity and mortality.1 Therefore, understanding the cardiovascular safety of glucose‐lowering treatment regimens is particularly important. In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration provided guidance for assessing cardiovascular risk when developing new antihyperglycaemic medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.2 Since this guidance was issued, numerous large‐scale cardiovascular outcomes trials of antihyperglycaemic medications have been conducted.

The cardiovascular safety of basal insulin glargine 100 units/mL (glargine U100) and insulin degludec (degludec) was established by the open‐label ORIGIN and double‐blind DEVOTE randomized trials, respectively, both of which included patients at high risk of cardiovascular events.3, 4 In 2011, the final results from the Outcome Reduction with Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial had shown that glargine U100 did not significantly affect the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) versus standard care in people with cardiovascular risk factors and impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes [hazard ratio (HR) 1.02 (0.94; 1.11)95% CI].3 In 2016, the final results from the Trial Comparing Cardiovascular Safety of Insulin Degludec versus Insulin Glargine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes at High Risk of Cardiovascular Events (DEVOTE) showed that degludec was non‐inferior to glargine U100 with respect to the incidence of MACE (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or non‐fatal stroke) in people with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk [HR 0.91 (0.78; 1.06)95% CI].4

In the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial, which included patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk receiving standard care, the glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist (GLP‐1RA) liraglutide significantly reduced the relative risk of MACE by 13%, the risk of cardiovascular death by 22% and the risk of all‐cause mortality by 15% versus placebo.5 Liraglutide also reduced the proportion of patients undergoing treatment intensification with antihyperglycaemic medications, including insulin, and the risks of severe hypoglycaemia and confirmed hypoglycaemia versus placebo.5 Based on the results of the LEADER trial, liraglutide was recommended as a treatment option in the treatment guidelines for patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease.6, 7

Consensus guidelines support the combination of a basal insulin and a GLP‐1RA as a treatment option for individuals with type 2 diabetes.7, 8, 9 For example, triple therapy, which can include the combination of metformin and a GLP‐1RA with basal insulin (or oral antihyperglycaemic drugs), is recommended if a patient with type 2 diabetes has not achieved his/her HbA1c target after 3 months of dual therapy.7, 8, 9 Combining injectable therapies consisting of basal insulin and a GLP‐1RA, usually with metformin (with or without another non‐insulin agent), should also be considered if the patient has not achieved the HbA1c target after 3 months of triple therapy using another regimen,8 or when blood glucose is ≥16.7 mmol/L, HbA1c ≥ 10% (≥86 mmol/mol) or the patient has symptoms of hyperglycaemia.7, 8

Clinical studies evaluating insulin and GLP‐1RA combination therapy (both fixed and free combinations) for type 2 diabetes have shown beneficial effects of this regimen on glycaemic control and body weight, or weight neutrality, versus comparators.10, 11, 12, 13 Some insulin/GLP‐1RA combinations also allow for reductions in existing insulin doses.10, 11, 12, 13 Furthermore, adding a GLP‐1RA to insulin therapy has been shown to decrease the risk of hypoglycaemia, even with improved HbA1c levels.9, 13, 14, 15

The aim of this post hoc analysis was to compare the associations between concomitant liraglutide use versus no liraglutide use and the occurrence of MACE and all‐cause mortality among patients receiving basal insulin (either degludec or glargine U100) in DEVOTE. This analysis was also repeated for the individual MACE components, serious adverse events and severe hypoglycaemic episodes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Trial design

The design of DEVOTE (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01959529) has been described previously.4, 16 The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice.17, 18 The protocol was approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each trial centre, and each participant provided written informed consent before any trial‐related activities.4

Briefly, DEVOTE was a treat‐to‐target, randomized, double‐blind, active comparator‐controlled cardiovascular outcomes trial conducted in 20 countries.4, 16 DEVOTE enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes being treated with at least one oral or injectable antihyperglycaemic agent who had HbA1c ≥7% (53 mmol/mol) or, if they had HbA1c <7% (53 mmol/mol), were treated with ≥20 units/d of basal insulin.4 Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged ≥50 years and had at least one co‐existing cardiovascular condition or chronic kidney disease, or if they were aged ≥60 years and had at least one cardiovascular risk factor.4

From November 2013, 7637 participants were randomized 1:1 to receive degludec or glargine U100 in a blinded fashion, both in identical 10 mL vials containing 100 U/mL, added to standard care and administered once daily between dinner and bedtime.4 Randomized participants could continue their pretrial antihyperglycaemic therapy, except for basal and premix insulins, which were discontinued at randomization.4

The primary composite outcome was the time from randomization to the first occurrence of cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction or non‐fatal stroke (MACE). DEVOTE was designed to continue until at least 633 MACE (confirmed by a central, blinded Event Adjudication Committee) had occurred.4 Overall, the median observation time was 1.99 (0‐2.75) years.

Secondary outcomes included the time from randomization to death from any cause (all‐cause mortality), serious adverse events and adjudicated severe hypoglycaemia.4 Severe hypoglycaemia was defined, in accordance with criteria recommended by the American Diabetes Association,19 as an episode requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer carbohydrate or glucagon or to take other corrective actions.4

2.2. Statistical methods

In these post hoc analyses, HRs comparing concomitant liraglutide use with no concomitant liraglutide use were calculated for the time to the first occurrence of confirmed MACE (primary composite outcome) and for the time to the first occurrence of confirmed individual MACE components (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction and non‐fatal stroke). The same analyses were also applied to the first occurrence of confirmed all‐cause mortality events, serious adverse events and severe hypoglycaemic events including all randomized participants. These analyses used a Cox regression model that adjusted for treatment (degludec or glargine U100) as a fixed factor and liraglutide use (Yes/No) at any time during the trial as a time‐varying factor, without interaction between the two factors. Thus, these analyses account for patients' liraglutide use in a time‐dependent manner by handling initiation, interruption or discontinuation of liraglutide treatment during the trial. Patients who did not experience the event of interest in a particular analysis were right censored at the end of the trial and contributed to the analysis with event‐free exposure time (Figure S1, Supporting Information).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted that adjusted for additional baseline covariates, including age, sex, smoking status, race, diabetes duration, cardiovascular risk group, insulin treatment, HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hepatic impairment category and renal impairment category.

Further sensitivity analyses, conducted for MACE and all‐cause mortality, examined the influence of extending the time window in which patients were considered to be receiving liraglutide after this treatment had, in fact, been discontinued (by 7, 30, 60 or 90 days). This potentially provided more conservative estimates of the effect of concomitant liraglutide use with each prolongation of the time window for liraglutide use, by ascribing potential events occurring (shortly) after a treatment pause to the liraglutide group. Lastly, a sensitivity analysis for MACE and all‐cause mortality was conducted where patients were considered to be liraglutide users from time of first initiation of liraglutide use until the first event or right censoring (until end of trial or lost to follow‐up). These analyses thereby extended the time window in which MACE and/or all‐cause mortality events were considered to be concomitant with liraglutide use, although liraglutide use had been stopped. These analyses are important to assess a potential tendency for patient deterioration leading to changes in concomitant liraglutide use.

Due to the time‐varying nature of the exposure for the present analyses, patients could be included or excluded from the “concomitant liraglutide use” group at different time points. Therefore, a traditional comparison of baseline characteristics was neither feasible nor appropriate. However, comparing the characteristics of patients who received liraglutide at any time during the trial and patients who never used liraglutide during the trial can provide some information (Table S1, Supporting Information).

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to account for the possible impact of concomitant sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2 (SGLT‐2) inhibitor use on outcomes. For these analyses, patients who used SGLT‐2 inhibitors at baseline were excluded from the concomitant liraglutide use group and included in the no concomitant liraglutide use group.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Exposure to liraglutide during the trial

Among all randomized participants at baseline, only a limited number of patients used a GLP‐1RA (n = 604; 7.9%). Of these patients, 436 (72.2%) were receiving liraglutide at baseline. Based on the total randomized population, 436 (5.7%) were receiving liraglutide at baseline, 187 (2.4%) initiated liraglutide after baseline and 210 (2.7%) discontinued liraglutide after baseline. Mean liraglutide exposure from randomization was 530.2 days [interquartile range: 476 days (Q1: 277; Q3: 753)] for all patients using liraglutide at any time across the full analysis set irrespective of events occurred.

3.2. Time to first MACE, individual MACE components and all‐cause mortality

Among patients who experienced events while exposed to liraglutide, mean liraglutide exposure from randomization to the first confirmed MACE was 302.1 days. The corresponding value for all‐cause mortality was 348.8 days.

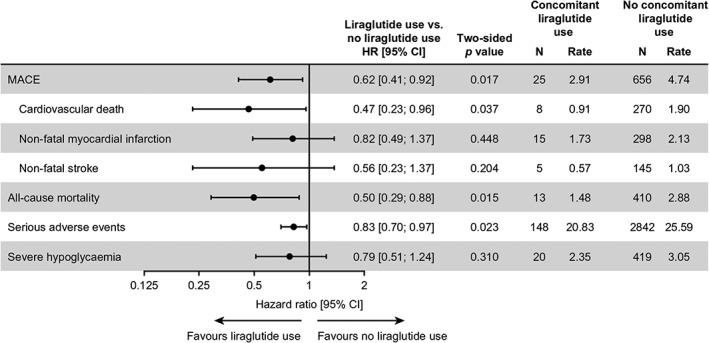

Concomitant liraglutide use was associated with a significantly lower rate of MACE [HR 0.62 (0.41; 0.92)95% CI] compared with no concomitant liraglutide use (Figure 1 and Table 1). Concomitant liraglutide use was also associated with a significantly lower rate of all‐cause mortality versus no concomitant liraglutide use [HR 0.50 (0.29; 0.88)95% CI] (Figure 1 and Table 2). This observation for MACE was driven by lower rates of all three individual MACE components with concomitant liraglutide versus no concomitant liraglutide use, although only the rate of cardiovascular death was significantly lower [HR for cardiovascular death 0.47 (0.23; 0.96)95% CI; HR for non‐fatal myocardial infarction 0.82 (0.49; 1.37)95% CI; HR for non‐fatal stroke 0.56 (0.23; 1.37)95% CI] (Figure 1). Importantly, all of these results from these analyses were observed while the overall effect of degludec versus glargine U100 seen in the primary analysis was preserved (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Analyses of major clinical outcomes by time‐varying liraglutide use. Full analysis set (all randomized patients). HRs presented are for time to the first confirmed event (in days), comparing concomitant liraglutide use with no concomitant liraglutide use. HRs are based on a Cox regression model adjusted for treatment and time‐varying liraglutide use at any time during the trial, without interaction. Thus, the analyses are adjusted for patients initiating, interrupting or discontinuing liraglutide treatment during the trial. For one patient who experienced an event occurring on the same day as liraglutide initiation, half a day was added to the day of the event. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; N, number of events; Rate, events per 100 patient‐years of observation

Table 1.

MACE by liraglutide use

| Degludec/glargine U100 with concomitant liraglutide use | Degludec/glargine U100 with no concomitant liraglutide use | Liraglutide use vs. no liraglutide use HR [95% CI] | Two‐sided P‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate | N | Rate | |||

| Unadjusted main analysis | 25 | 2.91 | 656 | 4.74 | 0.62 [0.41; 0.92] | 0.0174 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||

| Adjusted for additional baseline covariates | 25 | 2.91 | 656 | 4.74 | 0.56 [0.36; 0.88] | 0.0119 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 7 days | 27 | 3.13 | 654 | 4.73 | 0.66 [0.45; 0.97] | 0.0366 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 30 days | 28 | 3.20 | 653 | 4.73 | 0.68 [0.46; 0.99] | 0.0434 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 60 days | 29 | 3.25 | 652 | 4.72 | 0.69 [0.48; 1.00] | 0.0499 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 90 days | 29 | 3.20 | 652 | 4.73 | 0.68 [0.47; 0.98] | 0.0393 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended maximally | 33 | 3.07 | 648 | 4.76 | 0.64 [0.45; 0.92] | 0.0140 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; glargine U100, insulin glargine 100 units/mL; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; N, number of events; Rate, events per 100 patient‐years of observation.

Full analysis set (all randomized patients). HRs presented are for time to the first confirmed event (in days), comparing concomitant liraglutide use with no concomitant liraglutide use. HRs are based on a Cox regression model adjusted for treatment and time‐varying liraglutide use at any time during the trial, without interaction. Thus, the analyses are adjusted for patients initiating, interrupting or discontinuing liraglutide treatment during the trial. For one patient who experienced an event occurring on the same day as liraglutide initiation, half a day was added to the day of the event.

Table 2.

All‐cause mortality by liraglutide use

| Degludec/glargine U100 with concomitant liraglutide use | Degludec/glargine U100 with no concomitant liraglutide use | Liraglutide use vs. no liraglutide use HR [95% CI] | Two‐sided P‐value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate | N | Rate | |||

| Unadjusted main analysis | 13 | 1.48 | 410 | 2.88 | 0.50 [0.29; 0.88] | 0.0151 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||

| Adjusted for additional baseline covariates | 13 | 1.48 | 410 | 2.88 | 0.55 [0.32; 0.96] | 0.0362 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 7 days | 13 | 1.47 | 410 | 2.88 | 0.50 [0.29; 0.87] | 0.0143 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 30 days | 13 | 1.45 | 410 | 2.88 | 0.49 [0.28; 0.86] | 0.0122 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 60 days | 13 | 1.42 | 410 | 2.89 | 0.48 [0.28; 0.84] | 0.0102 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended by 90 days | 13 | 1.40 | 410 | 2.89 | 0.48 [0.27; 0.83] | 0.0084 |

| Time window for liraglutide use extended maximally | 19 | 1.72 | 404 | 2.88 | 0.57 [0.36; 0.91] | 0.0184 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; glargine U100, insulin glargine 100 units/mL; N, number of events; Rate, events per 100 patient‐years of observation.

Full analysis set (all randomized patients). HRs presented are for time to the first confirmed event (in days), comparing concomitant liraglutide use with no concomitant liraglutide use. HRs are based on a Cox regression model adjusted for treatment and time‐varying liraglutide use at any time during the trial, without interaction. Thus, the analyses are adjusted for patients initiating, interrupting or discontinuing liraglutide treatment during the trial. For one patient who experienced an event occurring on the same day as liraglutide initiation, half a day was added to the day of the event.

Among the 436 patients who were receiving liraglutide at baseline, 27 first confirmed MACE were reported [3.1 events/100 patient‐years of observation (PYO)] compared with 654 first confirmed MACE in patients not using liraglutide at baseline (4.7 events/100 PYO). Liraglutide use at baseline was associated with a significantly lower rate of MACE [HR 0.65 (0.45; 0.96)95% CI, P = 0.03] compared with no liraglutide use, irrespective of the randomized basal insulin.

3.3. Time to first serious adverse event and first severe hypoglycaemic episode

Concomitant liraglutide use was associated with a significantly lower rate of serious adverse events versus no concomitant liraglutide use [HR 0.83 (0.70; 0.97)95% CI] (Figure 1). There was also a trend for a lower rate of severe hypoglycaemia with concomitant liraglutide use versus no concomitant liraglutide use, but the difference was not statistically significant [HR 0.79 (0.51; 1.24)95% CI] (Figure 1).

3.4. Sensitivity analyses

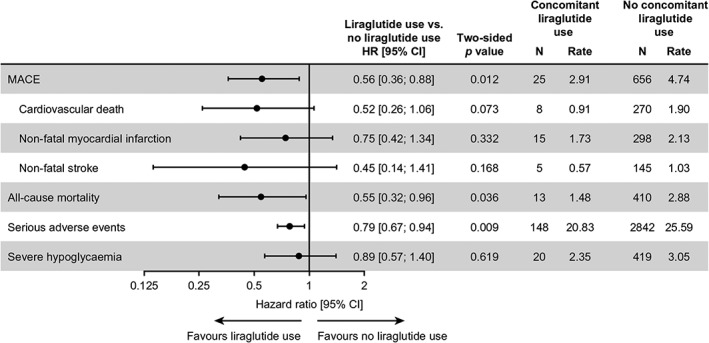

HRs from the sensitivity analyses adjusted for additional baseline covariates were consistent with those obtained in the main analyses of the time to first MACE, individual MACE components and all‐cause mortality events (Figure 2). However, after adjustment for additional baseline covariates, the HR for one individual MACE component, cardiovascular death, with concomitant liraglutide use versus no concomitant liraglutide use, was no longer statistically significant, although the HR was similar to that before adjustment [HR 0.52 (0.26; 1.06)95% CI; P = 0.0727].

Figure 2.

Adjusted analyses of major clinical outcomes by time‐varying liraglutide use. Full analysis set (all randomized patients). HRs presented are for time to the first confirmed event (in days), comparing concomitant liraglutide use with no concomitant liraglutide use. HRs are based on a Cox regression model adjusted for treatment and time‐varying liraglutide use at any time during the trial alongside additional baseline factors and covariates, including age, sex, smoking status, race, diabetes duration, cardiovascular risk group, insulin treatment, HbA1c, BMI, systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, hepatic impairment category and renal impairment category, all without interaction. Thus, the analyses are adjusted for patients initiating, interrupting or discontinuing liraglutide treatment during the trial. For one patient who experienced an event occurring on the same day as liraglutide initiation, half a day was added to the day of the event. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; N, number of events; Rate, events per 100 patient‐years of observation, BMI, body mass index; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein

The main analyses and sensitivity analyses adjusted for additional baseline covariates provided similar results for the time to the first serious adverse event (Figure 2). Similarly, consistent results were obtained for the time to first severe hypoglycaemic episode following adjustment for additional baseline covariates (Figure 2).

When the time window in which patients were considered to be receiving liraglutide was extended by 7, 30, 60 or 90 days after the actual stop date, concomitant liraglutide use was associated with significantly lower rates of MACE and all‐cause mortality in each scenario, compared with no concomitant liraglutide use (Tables 1 and 2). A similar result was found when the time window was extended maximally [i.e. patients were considered to be liraglutide users from time of first use of liraglutide until the first event or right censoring (end of trial or lost to follow‐up)].

When SGLT‐2 inhibitor use was taken into account, similar results to the main analysis and the sensitivity analyses adjusted for baseline characteristics were observed (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

3.5. Patient characteristics

Overall, the group who received liraglutide at any time during the trial (n = 623) and the group who never used liraglutide during the trial (n = 7014) were similar at screening or baseline. At screening or baseline, the group who received liraglutide at any time during the trial had numerically higher mean body weight and BMI, but numerically lower mean HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol than the group who never received liraglutide during the trial. Additional patient characteristics and antihyperglycaemic and cardiovascular medication use for these two groups at screening or baseline are shown in Table S1, Supporting Information.

3.6. Insulin use

After 24 months of randomized treatment, mean basal insulin doses were the same for patients who did or did not receive liraglutide at any time (0.7 ± 0.4 units/kg) (Figure S3 and Table S2, Supporting Information). Mean bolus insulin doses used after 24 months of randomized treatment were slightly lower in the group who received liraglutide at any time (0.5 ± 0.5 units/kg) than in the group who never used liraglutide (0.6 ± 0.5 units/kg) (Figure S4 and Table S2, Supporting Information).

4. DISCUSSION

These post hoc analyses of data from DEVOTE examined if the use of liraglutide was associated with differences in the occurrence of MACE and all‐cause mortality in users of basal insulin (degludec or glargine U100) with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. Pooled data from patients receiving degludec or glargine U100 showed that concomitant liraglutide use versus no concomitant liraglutide use was associated with a 38% lower HR for MACE and a 50% lower HR for all‐cause mortality (both statistically significant), suggesting that the combination of liraglutide and basal insulin may be associated with a cardiovascular benefit. This is in line with the main finding from the LEADER trial,5 where liraglutide significantly reduced the risks of MACE, cardiovascular death and all‐cause mortality versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. Similarly, in a post hoc analysis of basal insulin‐treated patients in LEADER, treatment with liraglutide versus placebo resulted in a cardiovascular risk reduction similar to the results from the main trial and was also associated with a 50% reduction in severe hypoglycaemia.20 In addition, in the present study a range of sensitivity analyses were conducted for these outcomes, including adjusting for additional baseline covariates and extending the time window for liraglutide use. Results from these sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main findings, suggesting that they are robust.

There are a number of observations from the LEADER trial that provide supporting context for our analysis. Observations from our post hoc analysis are supported by analyses of LEADER subgroups receiving insulin with or without an oral antihyperglycaemic agent (OHA) at baseline.5 In both of these LEADER subgroups, fewer patients experienced MACE with liraglutide versus placebo, although the differences did not reach statistical significance [HR for insulin with OHA at baseline 0.89 (0.74; 1.06)95%CI; HR for insulin without OHA at baseline 0.86 (0.63; 1.17)95% CI].5 However, the LEADER trial was not powered to detect significant differences in MACE in the post hoc analysis because of the smaller number of patients included in these subgroups versus the overall LEADER population.5 Additionally, the observation that liraglutide reduced treatment intensification with antihyperglycaemic medications during the LEADER trial, including insulin,5 complicates the interpretation of these data.

Our analysis only included those patients treated with liraglutide in DEVOTE and not all GLP‐1RAs. This was primarily because of the small proportion of patients who used a GLP‐1RA that was not liraglutide, which would not have allowed for a meaningful comparison. Furthermore, the cardiovascular benefit of some other GLP‐1RAs had not been shown. On this basis, only those patients treated with liraglutide were investigated. In the United States, liraglutide is indicated to reduce the risk of MACE in adults with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease.21 In addition, treatment guidelines were updated to mention liraglutide as the GLP‐1RA to be used in patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease.6, 7, 8 The mechanisms underlying the reduction in MACE with liraglutide have not been fully established, but an antiatherogenic effect may be involved.22 Reductions in body weight and visceral fat, improvements in insulin resistance associated with non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis, lipid profiles, anti‐inflammatory effects and reductions in hypoglycaemia and HbA1c may contribute to the cardiovascular benefits of liraglutide.9, 22, 23 Moreover, current guidelines support the combined use of a basal insulin and a GLP‐1RA (both free and fixed combinations) when individuals with type 2 diabetes require treatment intensification.7, 8, 9 Therefore, as more patients use the GLP‐1RA/basal insulin combination, it is increasingly important to understand the cardiovascular profile of these combinations, especially as patients with type 2 diabetes are at high risk of cardiovascular events. The present analysis revealed a 53% lower HR of cardiovascular death (significant) and a 21% lower HR of severe hypoglycaemia (non‐significant) with concomitant liraglutide use versus no concomitant liraglutide use.

This study has several limitations. This was a post hoc analysis, and our data show associations between liraglutide use and treatment outcomes. In addition, as these were subgroup analyses, the 95% CIs for the HRs comparing events of interest with liraglutide use versus no liraglutide use were relatively wide, particularly for the individual MACE components. Hence, the parameter estimates are somewhat imprecise, but the patterns were consistent. Concomitant and non‐concomitant liraglutide use were not randomized groups in DEVOTE. However, various sensitivity analyses supported the robustness of the main finding. Furthermore, the sensitivity analyses did not account for differences in insulin dose. However, basal insulin doses after 24 months of treatment were comparable in the concomitant and non‐concomitant liraglutide use groups, and therefore this factor would be expected to have a limited impact on the analyses. In addition, as DEVOTE recruited and studied patients with type 2 diabetes who were at high risk for cardiovascular events, our findings may be more relevant to patients with established cardiovascular disease or patients over 60 years of age with one or more cardiovascular risk factors. Concomitant liraglutide use was associated with a lower risk of adverse outcomes. Yet, it could be argued that prior to experiencing a cardiovascular event a patient would feel unwell and may discontinue liraglutide, which would disfavour the control group and potentially inflate the effect sizes associated with exposure. However, the sensitivity analysis that applied an extended time window to liraglutide exposure in fact showed that the main findings were robust. Lastly, potential between‐group differences were noted in the baseline characteristics of patients who did or did not use liraglutide during the trial at any time. These differences may be because of socioeconomic factors and treatment goals for individual patients, which were not possible to account for in this analysis. However, the sensitivity analyses that adjusted for a range of additional covariates were consistent with those obtained in the main analyses, suggesting that these factors did not impact the prevalence of these outcomes. Nevertheless, residual confounding cannot be excluded.

This study also had a number of strengths. This analysis was based on data from a large, double‐blind, cardiovascular outcomes trial, with independent adjudication of cardiovascular and severe hypoglycaemic events. In addition, the sensitivity analyses that adjusted for several baseline covariates and extended the time window for liraglutide use, maximally penalizing liraglutide use, support our main findings. Lastly, the findings from this post hoc analysis are in line with the overall findings from DEVOTE, LEADER, the LEADER subanalyses and also data on cardiovascular risk markers seen with degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira),4, 24 thereby contributing significantly to the body of evidence supporting the combination of liraglutide and basal insulin in a free or fixed combination.

Overall, results from the present analyses indicate that the use of liraglutide in combination with basal insulin is associated with a lower cardiovascular risk, in terms of a significantly lower risk of first MACE and all‐cause mortality, compared with no liraglutide use. These results, in line with the DEVOTE and LEADER primary results, provide important and novel information for physicians prescribing a combination of insulin and liraglutide that may extend to fixed‐dose insulin and GLP‐1RA combinations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Design: Kirstine Brown‐Frandsen, John Buse, Randi Grøn, Mattis Flyvholm Ranthe; Conduct/data collection: Randi Grøn, Mattis Flyvholm Ranthe; Analysis: all authors; Writing: all authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

K.B.‐F. is a full‐time employee of, and holds stock in, Novo Nordisk A/S. S.S.E. has received personal fees related to Data Monitoring Committees from CTI BioPharma, Arena Pharmaceuticals, SFJ Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin, Medivation, Biom'up, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Dynavax, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Research, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sarepta Therapeutics and Xoma; personal fees related to other statistical consulting from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celltrion, Daiichi Sankyo, Nektar Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Sage Therapeutics, Shire, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Collegium Pharmaceutical, Intercept, Coherus BioMedical and Emmaus Life Sciences; and research grant support from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). D.K.M. has received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Research and Development LLC, Sanofi US, Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp., Eli Lilly USA, Novo Nordisk, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Eisai and Esperion. T.R.P. has received research support from Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca (paid directly to the Medical University of Graz); personal fees as a consultant from AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Roche Diabetes Care; and is the Chief Scientific Officer of Center for Biomarker Research in Medicine (CBmed), a public‐funded biomarker research company. N.R.P. has received personal fees from Servier, Takeda, Novo Nordisk and AstraZeneca in relation to speakers' fees and advisory board activities (concerning diabetes mellitus); and research grants for his research group (relating to type 2 diabetes mellitus) from Diabetes UK, National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (NIHR EME), Julius Clinical and the British Heart Foundation. R.E.P.'s services were paid directly to Florida Hospital, a non‐profit organization. He received consultancy and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Takeda and Novo Nordisk; consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Ligand Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer and Eisai, Inc.; and research grants from Gilead Sciences, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Ligand Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eli Lilly, Merck, Sanofi US LLC and Takeda. B.Z. has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk; and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. M.F.R., R.G., M.L. and P.O. are full‐time employees of, and hold stock in, Novo Nordisk A/S. A.C.M. was a full‐time employee of Novo Nordisk until 30 June 2018; he currently serves as an independent consultant and holds shares in Novo Nordisk A/S. J.B.B. has been an advisor with all fees paid to the University of North Carolina by Adocia, AstraZeneca, Dance Biopharm, Eli Lilly, MannKind, NovaTarg, Novo Nordisk, Senseonics and vTv Therapeutics; he has received grant support from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and vTv Therapeutics; he is a consultant to Neurimmune AG and holds stock options in Mellitus Health, PhaseBio and Stability Health; and he is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR002489).

Data sharing statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supporting information

Table S1. Baseline characteristics and antihyperglycaemic medication use of patients who received liraglutide at any time and patients who never used liraglutide.

Table S2. Mean insulin dose by liraglutide use.

Figure S1. Schematic illustration of time‐varying liraglutide use and first MACE in patients receiving basal insulin.

Figure S2. Analyses of major clinical outcomes by time‐varying liraglutide use adjusted for baseline SGLT‐2 inhibitor use.

Figure S3. Mean basal insulin use over time.

Figure S4. Mean bolus insulin use over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The trial and this secondary analysis were funded by Novo Nordisk, with all analyses planned and conducted in collaboration with the Executive Steering Committee. All authors had full access to the data and shared final responsibility for the content of the manuscript and the decision to submit for publication.

We thank the trial investigators, trial staff and trial participants for their participation, and Francesca Hemingway and Beverly La Ferla from Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc (funded by Novo Nordisk), for providing medical writing and editorial support. DEVOTE research activities were supported at numerous US centres by Clinical and Translational Science Awards from the National Institutes of Health's “National Center for Advancing Translational Science.”

Brown‐Frandsen K, Emerson SS, McGuire DK, et al. Lower rates of cardiovascular events and mortality associated with liraglutide use in patients treated with basal insulin: A DEVOTE subanalysis (DEVOTE 10). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1437–1444. 10.1111/dom.13677

Alan C. Moses ‐ Affiliation correct at the time of the trial.

Peer Review The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.13677.

Funding information The trial and secondary analysis were funded by Novo Nordisk.

REFERENCES

- 1. Diabetes mellitus: a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. A joint editorial statement by the American Diabetes Association; The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; The Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International; The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; and The American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100:1132‐1133. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Diabetes+mellitus:+a+major+risk+factor+for+cardiovascular+disease [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. FDA . Guidance for industry. Diabetes mellitus — evaluating cardiovascular risk in new antidiabetic therapies to treat type 2 diabetes. December 2008. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM071627.pdf. Accessed March 2019.

- 3. Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, et al. Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:319‐328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marso S, McGuire DK, Zinman B, et al. Efficacy and safety of degludec versus glargine in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:723‐732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‐Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311‐322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Diabetes Association . Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S1‐S135.27979885 [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Diabetes Association . Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(suppl 1):S1‐S159.29222369 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davies M, D'Alessio D, Fradkin J, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669‐2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm – 2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T. Combining GLP‐1 receptor agonists with insulin: therapeutic rationales and clinical findings. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:3‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:1056‐1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lind M, Hirsch IB, Tuomilehto J, et al. Liraglutide in people treated for type 2 diabetes with multiple daily insulin injections: randomised clinical trial (MDI Liraglutide trial). BMJ. 2015;351:h5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valentine V, Goldman J, Shubrook JH. Rationale for, initiation and titration of the basal insulin/GLP‐1RA fixed‐ratio combination products, IDegLira and IGlarLixi, for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:739‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lingvay I, Pérez Manghi F, García‐Hernández P, et al. Effect of insulin glargine up‐titration vs insulin degludec/liraglutide on glycated haemoglobin levels in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: the DUAL V randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:898‐907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Billings LK, Doshi A, Gouet D, et al. Efficacy and safety of IDegLira versus basal‐bolus insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin and basal insulin; DUAL VII randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1009‐1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marso SP, McGuire DK, Zinman B, et al. Design of DEVOTE (trial comparing cardiovascular safety of insulin Degludec vs insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular events) – DEVOTE 1. Am Heart J. 2016;179:175‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191‐2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) . ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: guideline for good clinical practice. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:199‐203. https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1384‐1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tack C, Desouza C, Bain SC, et al. Liraglutide effects in insulin‐treated patients in LEADER. Diabetes. 2018;67(suppl 1):A117. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liraglutide highlights of prescribing information 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/022341s027lbl.pdf. Accessed March 2019.

- 22. Vergès B, Charbonnel B. After the LEADER trial and SUSTAIN‐6, how do we explain the cardiovascular benefits of some GLP‐1 receptor agonists? Diabetes Metab. 2017;43(suppl 1):2S3‐2S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Armstrong MJ, Hull D, Guo K, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 decreases lipotoxicity in non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2016;64:399‐408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vilsbøll T, Belvins T, Bode BW, et al. IDegLira improves cardiovascular risk markers in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on basal insulin: analyses of DUAL II and DUAL V. Diabetologia. 2017;60(suppl 1):S50. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Baseline characteristics and antihyperglycaemic medication use of patients who received liraglutide at any time and patients who never used liraglutide.

Table S2. Mean insulin dose by liraglutide use.

Figure S1. Schematic illustration of time‐varying liraglutide use and first MACE in patients receiving basal insulin.

Figure S2. Analyses of major clinical outcomes by time‐varying liraglutide use adjusted for baseline SGLT‐2 inhibitor use.

Figure S3. Mean basal insulin use over time.

Figure S4. Mean bolus insulin use over time.