Abstract

Lymphoid specification is the process by which hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and their progeny become restricted to differentiation through the lymphoid lineages. The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors E2A and Lyl1 form a complex that promotes lymphoid specification. Here we demonstrate that Tal1, a Lyl1 related bHLH transcription factor that promotes T acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and is required for hematopoietic stem cell specification, erythropoiesis, and megakaryopoiesis, is a negative regulator of murine lymphoid specification. We demonstrate that Tal1 limits the expression of multiple E2A target genes in HSCs and controls the balance of myeloid versus T lymphocyte differentiation potential in lympho-myeloid primed progenitors. Our data provide novel insight into the mechanisms controlling lymphocyte specification and may reveal a basis for the unique functions of Tal1 and Lyl1 in T-ALL.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphocytes develop from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) via the progressive restriction of their developmental potential. Despite HSC heterogeneity (1), an early differentiation step results in a lympho-myeloid primed progenitor (LMPP) population that lacks megakaryocyte and erythrocyte potential but retains lymphoid and myeloid potential (2). LMPPs express low levels of myeloid and lymphoid lineage mRNAs, referred to as multi-lineage gene priming, and these gene programs are resolved as the cells become specified to the lymphoid or myeloid lineages. A subset of LMPPs lose myeloid potential and become restricted to lymphoid differentiation, a process associated with lymphoid gene priming (2). The development of LMPPs and their lymphoid specification is under the control of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors E2A, HEB, and Lyl1, which positively regulate lymphoid genes in these cells (3–5). However, these factors are expressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) raising the question of how their lymphoid specifying activities are restrained prior to lymphoid specification (4).

Tal1 and Lyl1 are Class II bHLH proteins that dimerize with the Class I proteins E2A and HEB (6). Tal1 plays a crucial role in HSC formation but it is not essential for long-term HSC (LT-HSC) function in post-natal mice due to redundancy with Lyl1 (7). Tal1 and Lyl1 are not expressed in T cell progenitors but their aberrant expression is associated with T lymphoblastic acute leukemia (T-ALL) and both proteins, at least in part, alter the functions of E2A and HEB (8); however, they are associated with distinct T-ALL phenotypes (9). Tal1 and Lyl1 have some unique functions with Tal1 playing a critical role in erythrocyte and megakaryocyte development and Lyl1 promoting lymphoid specification and development of early thymic progenitors (3, 10). Whether these unique functions reflect their differential expression or function has not been determined. Here, we demonstrate that Tal1 and Lyl1 have opposing functions in lymphoid specification where Tal1 restrains a subset of E2A-dependent genes in ST-HSCs and maintains the balance of lineage potentials in LMPPs. Our data support the hypothesis that Tal1 restrains E2A:Lyl1 mediated gene expression in HSPCs and limits the development of T cell biased LMPPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice were housed at the University of Chicago Animal Resource Center, and experiments were performed within the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Tal1flf, Lyl1−/− and E2a−/− mice were described (4, 7, 11). Tal1f/f mice were backcrossed an additional 5x onto the C57Bl/6 background. Rag2-GFP (12) and Vav-iCre (13) mice were purchased from Jackson Labs. All mice were analyzed between 8 and 14 weeks of age.

FACS and culture.

FACS and sorting was performed as described (4). The lineage cocktail included antibodies to CD11b, Gr1, CD11c, Ter119, NK1.1, B220, CD19, CD3, CD4, CD8 TCRβ and TCRδ. LSK = Lineage−CD117+SCA1+. LSK Flt3+CD62L+ or LSKFlt3+CD62L− cells were sorted and cultured at 3 concentrations (48 wells each) on OP9-DL4 stroma with Flt3L, IL-7, SCF, or Flt3L, IL-7, SCF and IL-2 or cultured on OP9 stroma with Flt3L, IL-7, SCF. FACS was used to identify CD25+ T cells at Day 16 or Day 13, or CD19+ B cells at Day 12 or Day 14. The frequency of cells with each potential was calculated using L-Calc software (Stemcell Technologies, Cambridge, Massachusetts).

LMPP reconstitution.

10–12 week old C57Bl/6 CD45.1 hosts were irradiated (500 rads) and reconstituted with 1:1 mixtures of sorted LMPPs from Tal1f/f or Tal1−/− donors and congenically marked competitor CD45.1+ LMPPs. Hosts were injected with 8000 – 10 000 cells of each cell type. Mice were analyzed by FACS 14 days after reconstitution.

RNA analysis

RNA was isolated using RNAeasy MicroKit (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time (qRT-)PCR was performed as described (4). Hprt mRNA was used for normalization. Primers are available upon request. Microarray analysis was performed as described (14). RNA-seq Library construction, sequencing and bioinformatics analysis was performed as described (15). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using Immgen gene sets (16). Microarray and RNA-sequencing data can be accessed in the Gene Expression Omnibus GSE126148 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE126148) and GSE126402 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE126402).

Graphs and Statistics

Graphs and statistics were generated using Excel or GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Tal1 does not regulate CLP or LMPP number.

E2A and Lyl1 are required for the development of LMPPs and for lymphoid gene priming in these cells (3–5). A comparison of E2A−/− and Lyl1−/− mice revealed a similar decrease in LMPP and CLP numbers suggesting that E2A and Lyl1 form a dimer that regulates lymphoid development (Supplemental Fig. 1). E2A−/− and Lyl1−/− CD135+ LSKs showed a similar loss of lymphoid-associated genes consistent with the requirement for both proteins in lymphoid specification (Supplemental Fig. 1). E2A and Lyl1 mRNAs, and E2A protein, were expressed at comparable levels in HSCs and LMPPs raising the question of why these proteins fail to activate lymphoid genes in HSCs (4) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Here we considered the possibility that an E protein interacting protein might antagonize E2A:Lyl1 function. We found that Tal1 mRNA was decreased in MPP and LMPP compared to HSC suggesting that Tal1 could impact E2A:Lyl1 function in HSCs (Supplemental Fig. 1)(17).

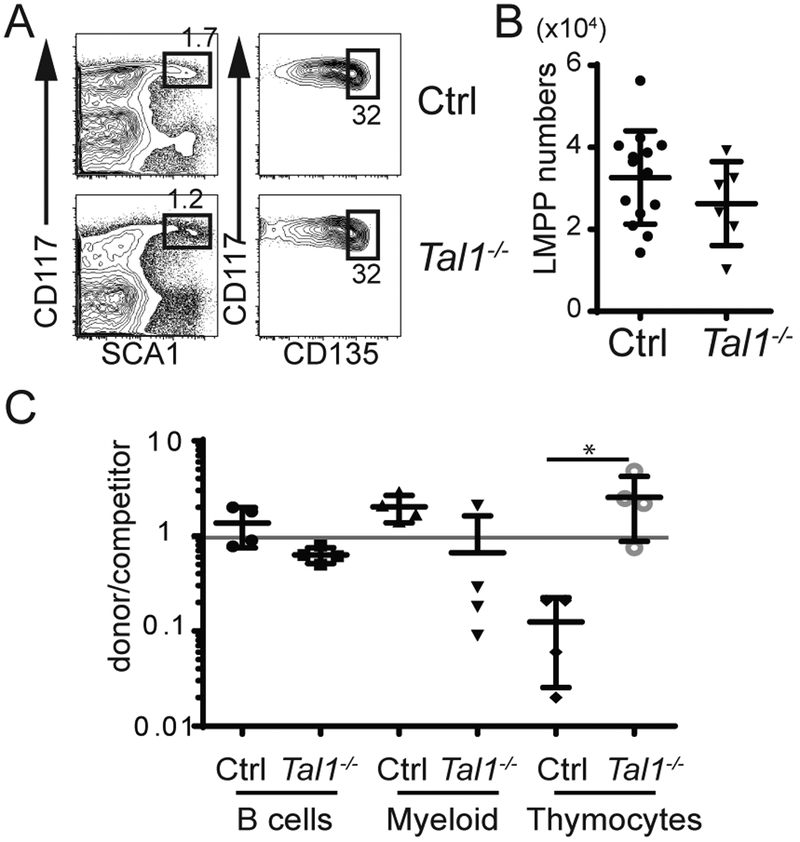

To determine whether Tal1 influenced the number of LMPPs, we created Vav-iCre+/− Tal1f/f (Tal1−/−) mice in which Tal1 was efficiently deleted in HSPCs (Supplemental Figure 2). Despite efficient deletion, LMPP and CLP numbers were similar in Tal1−/− and Tal1f/f controls (Ctrl) (Fig. 1A, B and Supplemental Figure 2). Tal1-deficiency did not appreciably affect B lymphocyte differentiation from LMPPs as measured by the frequency of splenic B cells derived from Tal1−/− LMPPs as compared to Ctrl LMPPs in transplanted mice under competitive conditions (Fig. 1C). However, Tal1−/− LMPPs generated an increased frequency of thymocytes compared to Ctrl LMPPs and, in some experiments, a lower frequency of splenic myeloid cells (Fig. 1C). These data led us to hypothesize that Tal1 influences the developmental potential of LMPPs.

FIGURE 1.

Tal1-deficiency does not impact LMPP or CLP numbers. (A) FACS for LMPPs (CD117+Sca1+CD135hi cells) cells in the Lin− fraction of Ctrl and Tal1−/− BM. (B) Number of LMPPs in the BM of Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. (C) Summary of at least 4 experiments depicting relative reconstitution of CD45.2 Ctrl or Tal1−/− donor versus competitor LMPPs for B cell, myeloid and T lineages. * P < 0.05 (Ordinary One-way ANOVA).

Tal1 limits Rag2 transcription in HSCs and LMPPs.

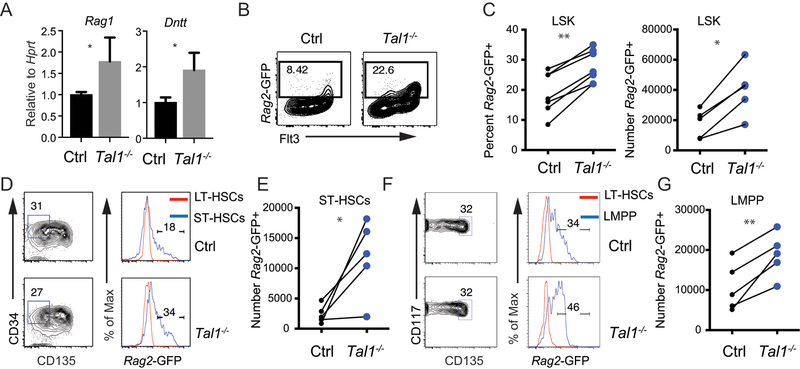

We tested whether Tal1 impacted LMPP gene expression by examining mRNA for Rag1 and Dntt, two known E2A target genes that are primed in LMPPs (18). By qRT-PCR Rag1 and Dntt mRNA were more highly expressed in Tal1−/− LMPPs compared to Ctrl LMPPs (Fig. 2A). To assess lymphoid gene priming at the single cell level we generated Tal1−/− and Ctrl mice that carried a transgene in which GFP is inserted into the Rag2 locus (RGFP) (12), since Rag2 is also an E protein target (17, 19). Analysis of the LSK compartment of Tal1−/− RGFP mice revealed an increased frequency and number of Rag2-GFP+ cells as compared to Ctrl RGFP mice (Fig. 2B, C). Further, Tal1−/− RGFP mice had a greater percentage and number of Rag2-GFP expressing ST-HSCs (LSK CD34+CD135−) and LMPPs (LSK CD135hi) as compared to Ctrl RGFP mice whereas LT-HSCs (LSK CD48−CD150+) did not express GFP (20, 21) (Fig. 2D–G). These data suggest that Tal1 repressed lymphoid priming as early as the ST-HSC population.

FIGURE 2.

Tal1 limits lymphoid gene transcription in ST-HSC and LMPP. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Rag1 and Dntt mRNA in sorted LMPPs from Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. Data are mean ± s.e.m from 3 independent experiments combined. *P < 0.05. (B) FACS showing CD135 and Rag2-GFP expression in LSKs. The frequency of Rag2-GFP+ cells is indicated. (C) Percent of LSKs expressing Rag2-GFP (left) and the number of Rag2-GFP+ LSKs (right) in the BM of Ctrl (black) and Tal1−/− (blue) mice. Each circle represents one mouse, line connects mice from the same experiment. (D) FACS showing CD34 and CD135 on LSKs for identification of ST-HSC (gated area) and Rag2-GFP expression (right panels) in ST-HSC as compared to LT-HSCs in Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. (E) Summary of the number of Rag2-GFP+ ST-HSC in Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. Each circle represents one mouse, line connects mice from the same experiment. (F) FACS showing CD135 and CD117 on LSK with LMPP gated (left panel) and Rag2-GFP expression in LMPP compared to LT-HSCs (right panel) in Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. (G) Number of Rag2-GFP+ LMPP in the BM of Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 (paired t-test). Data are representative of at least 5 independent experiments.

Ctrl and Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs had increased T cell and reduced myeloid potential compared to Rag2-GFP- LMPPs

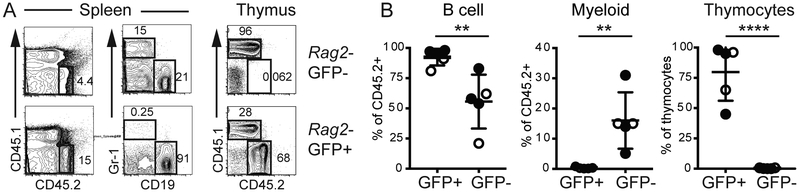

In wild-type mice a Rag1-GFP reporter is expressed in cells that have undergone lymphoid specification, defined as the loss of myeloid potential, whereas myeloid potential is present in the Rag1-GFP− population (18). Therefore, our data on Rag2-GFP expression could indicate that Tal1−/− LMPPs have more lymphoid specified cells and fewer cells with myeloid potential. Our competitive reconstitution experiments showed increased T cell potential but only a subtle and not significant decrease in myeloid reconstitution by Tal1−/− LMPPs. Given that Rag2-GFP+ frequency increased by nearly 50% in Tal1−/− LMPP but Rag2-GFP− frequency changed by less than 20%, we considered the possibility that the change in myeloid potential was not sufficient to be consistently detected in our in vivo assay. Therefore, to determine whether the increased frequency of Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs in Tal1−/− mice reflected a change in the frequency of myeloid and lymphoid potentials we isolated Rag2-GFP+ and Rag2-GFP− LMPPs from Tal1−/− and Ctrl mice and tested their differentiation potential in vivo. Both Rag2-GFP+ and Rag2-GFP− LMPPs (CD45.2+) gave rise to B cells in the spleens of recipient mice (Fig. 3A, B). In contrast, in vivo myeloid potential resided exclusively in the Rag2-GFP− fraction of both Tal1−/− and Ctrl LMPPs indicating that Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs are lymphoid restricted (Fig. 3A, B). In vitro experiments confirmed the enrichment of myeloid potential in Rag2-GFP- as compared to Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs (Supplemental Figure 3). Surprisingly, T cell potential resided almost entirely in Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs (Fig. 3A, B). Given that there are more Rag2-GFP+ LMPP in Tal1−/− mice than Ctrl mice, our data indicate that Tal1−/− mice had more T cell biased and myeloid depleted LMPP.

FIGURE 3.

Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs have B and T lymphocyte but little myeloid potential in vivo. (A) Sub-lethally irradiated CD45.1 host mice were reconstituted with Rag2-GFP+ or Rag2-GFP− LMPPs from CD45.2+ Ctrl (black) and Tal1−/− (blue) mice. CD45.2+ splenocytes and thymocytes from recipient mice were analyzed by FACS 14 days following reconstitution for myeloid cells (Gr-1) and B lymphocytes (CD19) or T lymphocytes (CD4 and CD8). (B) Summary of the percent of CD45.2+ splenocytes that were B lymphocytes or myeloid cells or the percent of thymocytes that were CD45.2+. Mice were reconstituted with Ctrl (white) or Tal1−/− (black) LMPPs. N=4. n=5, ** P < 0.01, and **** P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

To confirm that T cell biased LMPP were increased in Tal1−/− LMPP, we examined another surface marker associated with T cell potential. Previous studies implicated CD62L as a marker of BM LSKs that generate T lymphocytes and we found that CD62L+ LMPPs had greater T cell potential than CD62L− LMPPs in vitro (22, 23) (Supplemental Fig. 3). Interestingly, while B cells could be generated from both CD62L+ and CD62L− LMPPs, this potential was enriched in the Rag2-GFP− population (Supplemental Fig. 3). We also found more CD62L+ LMPPs in Tal1−/− mice as compared to Ctrl mice consistent with the increased T cell potential observed in Tal1−/− LMPP. (Supplemental Fig. 3). These data indicate that B and T cell potential can be independent in LMPP and that Tal1 restrains the frequency of LMPPs that are T cell biased.

Tal1 limits the expression of a subset of lymphoid-associated genes

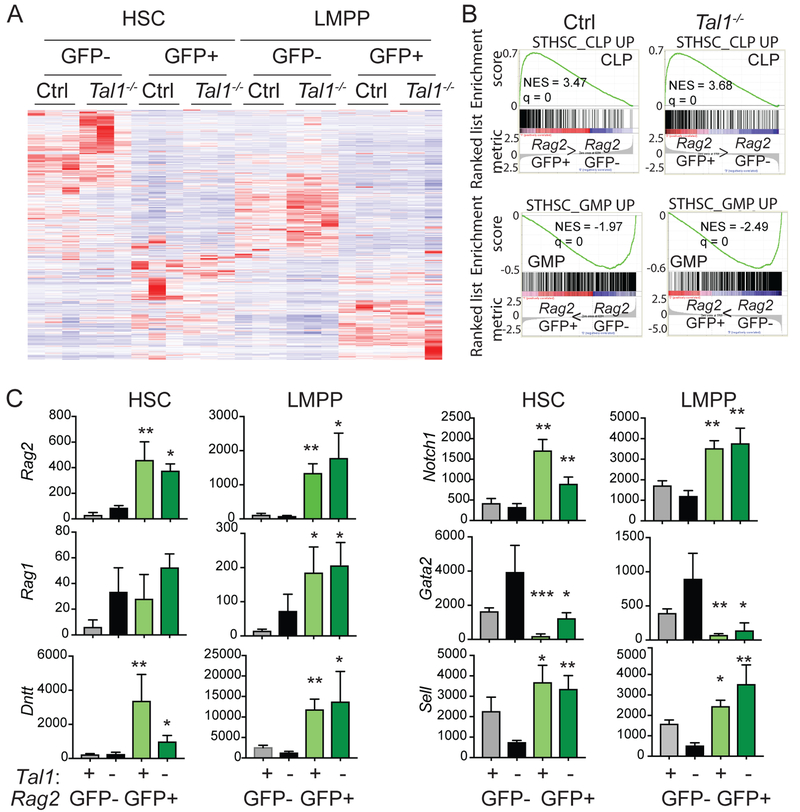

Our data suggest that Tal1 controls the frequency of LMPPs that express Rag2 and the frequency of LMPPs that are lymphoid lineage restricted and T cell biased. E2A proteins are required for the expression of a broad set of lymphoid genes in LMPPs that includes Rag2. Therefore, we questioned whether the increase in Rag2-GFP+ cells in the ST-HSC and LMPP population of Tal1−/− mice reflected a broad increase in lymphoid gene expression or whether Tal1 might be repressing a limited set of E protein target genes. To address this question, we sorted Rag2-GFP+ and Rag2-GFP− CD135− LSKs (HSC) and CD135hi LSKs (LMPPs) from Tal1−/− and Ctrl mice and isolated RNA for high throughput sequencing. Hierarchical clustering of the gene expression data revealed substantial differences between all of these populations with 590 genes being differentially expressed (Fig. 4A). “Hematopoietic cell lineage” was the top differentially regulated KEGG pathway (P=2.3 10^−7), a pathway that included both lymphoid and myeloid lineage genes. However, unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealed that the Rag2-GFP+ populations clustered together but were separated from the Rag2-GFP− populations (Supplemental Figure 4). Therefore, expression of Rag2-GFP in HSC or LMPP identifies cells with global gene expression profiles that are more related to each other than to the Rag2-GFP− cells with which they share a surface phenotype.

FIGURE 4.

Tal1-deficiency increased the frequency of HSC and LMPPs priming lymphoid genes. (A) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in triplicate samples of LSKs sorted on the basis of CD135 and Rag2-GFP expression. (B) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to determine the relative enrichment of CLP-associated (lymphoid) or GMP-associated (myeloid) genes in Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs versus Rag2-GFP− LMPPs. (C) Bar graphs depict normalized relative signal abundance of selected genes from RNA-seq analysis of HSC and LMPP from Ctrl RGFP (+) and Tal1−/− RGFP (–) mice sorted as Rag2-GFP+ or Rag2-GFP−. Data is from 3 independent experiments. * P < 0.05 ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0005 in Student’s t-test comparing Rag2-GFP+ and Rag2-GFP− population of the same genotype.

We next used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis to compare our sorted populations for their expression of genes more highly expressed in CLPs (lymphoid genes) or granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) (myeloid genes) as compared to ST-HSCs. Both Ctrl and Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs were significantly enriched for CLP-associated genes and depleted GMP-associated genes (Fig. 4B). Among the CLP genes that were increased in both Ctrl and Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ compared to Rag2-GFP− LMPPs were Rag1, Rag2, Il7r, Dntt, Blnk, Notch1, Ccn3 and Cmah, all of which were decreased in expression in E2A−/− LMPPs (4). Rag2-GFP+ HSCs from Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice cluster with Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs suggesting that these cells are also biased toward a lymphoid rather than myeloid gene expression program (Supplemental Fig. 4). Indeed, most of the lymphoid genes examined were more highly expressed in Ctrl Rag2-GFP+ HSC than in Rag2-GFP− HSCs, although only a few reached statistical significance including Rag2, Dntt, and Notch1 (Fig. 4C). Rag2, Dntt and Notch1 were also expressed at significantly higher levels in Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ HSCs as compare to Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP− HSCs (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Il7r, Blnk, Ccn3, and Cmah were not significantly increased in Ctrl or Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ HSC (Supplemental Figure 4). Sell, encoding CD62L, was more highly expressed in Rag2-GFP+ HSC and LMPP from both Tal1−/− and Ctrl mice than in Rag2-GFP− cells, as would be expected based on our FACS data, and consistent with its inclusion as a lymphoid-associated gene (Fig. 4C). Importantly, expression of the myeloid associated gene Gata2 was extinguished in Rag2-GFP+ HSCs and LMPPs from Ctrl mice but its expression was detected in Tal1−/− Rag2-GFP+ HSC suggesting that Rag2-GFP may be induced in cells that have not yet extinguished Gata2 in Tal1−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Our data indicate that expression of Rag2-GFP in Ctrl and Tal1−/− HSC is associated with increased expression of a subset of E protein-dependent lymphoid genes including Rag2, Dntt, Notch1, and Sell.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that Tal1 is a negative regulator of lymphoid gene priming and influences the fate of LMPPs. Tal1 restricts the ability of ST-HSCs to initiate expression of a subset of known E protein-dependent genes including Rag2, Dntt and Notch1 and promotes an LMPP compartment with a limited frequency of T lymphocyte biased cells. Our data also revealed that Tal1 primarily impacts the balance between myeloid and T lymphoid potential in LMPPs with less impact on B lymphoid potential, possibly due to its impact on the T cell associated genes Notch1 and Sell. Our observation that B and T cell potential are not synonymous is reminiscent of a recent study that demonstrated that B and T cell potential can arise separately during hematopoietic ontogeny (24). However, our findings are in contrast to E2A−/− mice in which LMPP, CLP and B cell numbers are dramatically affected, possibly due to a requirement for E2A in maintenance of all LMPPs and more mature lymphoid cells. Previous studies revealed that E2A maintains the quiescence of HSPCs and prevents their exhaustion by promoting expression of Cdkn1a (p21) (5). Indeed, E2A−/− and Lyl1−/− HSC, MPP and LMPP pass though the cell cycle more frequently than Ctrl cells and their exhaustion likely underlies the loss of LMPP and CLP numbers (3, 4). Cdkn1a transcription was not affected in Tal1−/− HSC or LMPPs consistent with our finding that total LMPP numbers are not affected in these mice and suggesting that Tal1 does not limit expression of all E2A target genes.

Our observation that Rag2-GFP+ HSCs clustered more closely with Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs than with Rag2-GFP− HSCs is striking in light of the recent evidence that the LT-HSC compartment contributes only rarely to hematopoietic output and that the majority of polyclonal steady state hematopoiesis derives from ST-HSCs, which can be biased to either lymphoid or myeloid outcomes (1). Our data suggest that Tal1 controls lymphoid bias in ST-HSCs and reconciles how it can be regulating lineage output in LMPPs in which its own expression is substantially reduced. However, the question of whether Tal1 impacts the emergence of lymphoid or T cell biased ST-HSC or their expansion or survival requires further investigation. Our gene expression data suggest differences between Rag2-GFP+ HSC from Ctrl and Tal1−/− mice including higher expression of Gata2 in the latter, an indication that Tal1 may be repressing Rag2 in Gata2 mRNA positive ST-HSC. Single cell gene expression analysis combined with clonal in vivo differentiation analysis may be helpful in demonstrating this point. Nonetheless, our data reveal an important role for Tal1 in limiting lymphoid gene priming and determining the frequency of lymphoid specified and T cell biased LMPP. Our data also suggest a possible mechanism by which re-expression of Tal1 or Lyl1 could contribute to distinct T-ALL phenotypes. In the context of T cell progenitors, Lyl1:E protein complexes could potentiate a T cell bias while also promoting self-renewal whereas Tal1:E protein complexes could antagonize the function of E proteins at multiple genes involved in T cell differentiation while activating genes that promote transformation.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Tal1 limits the number of ST-HSC that priming lymphoid genes

Tal1 limits the number of lymphoid gene priming Rag2-GFP+ LMPPs

Tal1 restrains the frequency of T lymphocyte biased LMPPs

Acknowledgements:

We thank L. Lenner, G. van der Voort, and S. Liang for technical support, J.C. Zuniga-Pflucker, M. Anderson, F. Gounari, M. Ciofani and the Kee Lab for helpful discussions, M. Goodell for the Lyl1−/− mice, H. Mikkola for Tal1f/f mice, and the University of Chicago Immunology Applications Core for assistance with cell sorting.

Funding was provided by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (R.dP.) the National Institutes of Health R01 AI1078267 and R01 AI106352 (B.L.K) and T32HD007009 (M.K.O.).

References

- 1.Haas S, Trumpp A, and Milsom MD. 2018. Causes and Consequences of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Heterogeneity. Cell Stem Cell 22: 627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luc S, Buza-Vidas N, and Jacobsen SE. 2008. Delineating the cellular pathways of hematopoietic lineage commitment. Semin Immunol 20: 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zohren F, Souroullas GP, Luo M, Gerdemann U, Imperato MR, Wilson NK, Gottgens B, Lukov GL, and Goodell MA. 2012. The transcription factor Lyl-1 regulates lymphoid specification and the maintenance of early T lineage progenitors. Nat Immunol 13: 761–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias S, Mansson R, Gurbuxani S, Sigvardsson M, and Kee BL. 2008. E2A proteins promote development of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Immunity 29: 217–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Q, Kardava L, St Leger A, Martincic K, Varnum-Finney B, Bernstein ID, Milcarek C, and Borghesi L. 2008. E47 controls the developmental integrity and cell cycle quiescence of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors. J Immunol 181: 5885–5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kee BL 2009. E and ID proteins branch out. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souroullas GP, Salmon JM, Sablitzky F, Curtis DJ, and Goodell MA. 2009. Adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells require either Lyl1 or Scl for survival. Cell Stem Cell 4: 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Neil J, Billa M, Oikemus S, and Kelliher M. 2001. The DNA binding activity of TAL-1 is not required to induce leukemia/lymphoma in mice. Oncogene 20: 3897–3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, Loh ML, Huard C, Raimondi SC, Behm FG, Pui CH, Downing JR, Gilliland DG, Lander ES, Golub TR, and Look AT. 2002. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 1: 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porcher C, Chagraoui H, and Kristiansen MS. 2017. SCL/TAL1: a multifaceted regulator from blood development to disease. Blood 129: 2051–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikkola HK, Klintman J, Yang H, Hock H, Schlaeger TM, Fujiwara Y, and Orkin SH. 2003. Haematopoietic stem cells retain long-term repopulating activity and multipotency in the absence of stem-cell leukaemia SCL/tal-1 gene. Nature 421: 547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu W, Misulovin Z, Suh H, Hardy RR, Jankovic M, Yannoutsos N, and Nussenzweig MC. 1999. Coordinate regulation of RAG1 and RAG2 by cell type-specific DNA elements 5’ of RAG2. Science 285: 1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogilvy S, Metcalf D, Gibson L, Bath ML, Harris AW, and Adams JM. 1999. Promoter elements of vav drive transgene expression in vivo throughout the hematopoietic compartment. Blood 94: 1855–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zook EC, Li ZY, Xu Y, de Pooter RF, Verykokakis M, Beaulieu A, Lasorella A, Maienschein-Cline M, Sun JC, Sigvardsson M, and Kee BL. 2018. Transcription factor ID2 prevents E proteins from enforcing a naive T lymphocyte gene program during NK cell development. Sci Immunol 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen JA, Woodard J, Mandal M, Clark MR, Bartom ET, Sigvardsson M, and Kee BL. 2017. EZH2 Regulates the Developmental Timing of Effectors of the Pre-Antigen Receptor Checkpoints. J Immunol 198: 4682–4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, and Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansson R, Hultquist A, Luc S, Yang L, Anderson K, Kharazi S, Al-Hashmi S, Liuba K, Thoren L, Adolfsson J, Buza-Vidas N, Qian H, Soneji S, Enver T, Sigvardsson M, and Jacobsen SE. 2007. Molecular evidence for hierarchical transcriptional lineage priming in fetal and adult stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Immunity 26: 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igarashi H, Gregory SC, Yokota T, Sakaguchi N, and Kincade PW. 2002. Transcription from the RAG1 locus marks the earliest lymphocyte progenitors in bone marrow. Immunity 17: 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monroe RJ, Seidl KJ, Gaertner F, Han S, Chen F, Sekiguchi J, Wang J, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Kelsoe G, and Alt FW. 1999. RAG2:GFP knockin mice reveal novel aspects of RAG2 expression in primary and peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity 11: 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, and Morrison SJ. 2005. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121: 1109–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietras EM, Reynaud D, Kang YA, Carlin D, Calero-Nieto FJ, Leavitt AD, Stuart JM, Gottgens B, and Passegue E. 2015. Functionally Distinct Subsets of Lineage-Biased Multipotent Progenitors Control Blood Production in Normal and Regenerative Conditions. Cell Stem Cell 17: 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry SS, Welner RS, Kouro T, Kincade PW, and Sun XH. 2006. Primitive lymphoid progenitors in bone marrow with T lineage reconstituting potential. J Immunol 177: 2880–2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry SS, Wang H, Pierce LJ, Yang AM, Tsai S, and Spangrude GJ. 2004. L-selectin defines a bone marrow analog to the thymic early T-lineage progenitor. Blood 103: 2990–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berthault C, Ramond C, Burlen-Defranoux O, Soubigou G, Chea S, Golub R, Pereira P, Vieira P, and Cumano A. 2017. Asynchronous lineage priming determines commitment to T cell and B cell lineages in fetal liver. Nat Immunol 18: 1139–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.