Abstract

Background:

Ectopic olfactory receptors (OR) are found in the skin but their expression and biological functions in normal skin and atopic dermatitis (AD) are unknown.

Objectives:

To characterize the expression of ORs in the skin and assess OR-mediated biological responses of primary human keratinocytes in the presence of odorant ligands.

Methods:

OR expression was examined by whole transcriptome sequencing of skin tape strips collected from AD and healthy controls (NC). OR10G7 and FLG-1 expression were analyzed by RT-PCR and immunostaining in AD and NC skin biopsies and primary human keratinocytes. ATP and cyclic AMP production by control and OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes in response to odorant stimulation with acetophenone and eugenol were assessed.

Results:

A total of 381 OR gene transcripts were detected in the skin samples, with the greatest OR expression detected in the skin tape strips, corresponding to the upper granular layer of the skin. OR10G7 expression was significantly increased in AD compared to NC skin biopsies (p=0.01) and inversely correlated with FLG-1 expression (p=0.009). OR10G7 expression was highest in undifferentiated AD keratinocytes and was down-regulated with progressive differentiation. Primary human keratinocytes produced ATP, an essential neurotransmitter in sensory pathways, in response to acetophenone and eugenol, odorants previously identified as potential ligands for this receptor. This response was abolished in OR10G7 siRNA-transfected keratinocytes.

Conclusions:

OR10G7 is expressed at significantly higher levels in undifferentiated AD keratinocytes compared to normal controls. OR10G7 is likely involved in the transmission of skin-induced chemosensory responses to odorant stimulation, which may modulate differential nociceptive responses in AD skin.

Keywords: Atopic Dermatitis, Olfactory receptor, sensory, ATP, keratinocytes

Capsule summary

Ectopic olfactory receptors, such as OR10G7, are differentially expressed in AD vs normal skin. Their functional role likely involves the transduction of skin-induced chemosensory responses to odorant stimulation, which may modulate differential nociceptive responses in AD skin.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disorder in the US.1 Associated complications of AD include bacterial superinfections, predisposition to food allergy and the atopic march as well as psychosocial sequelae.2 Intense chronic itching is a hallmark of the disease, which results in sleep loss, disruption of social functioning and poor quality of life in afflicted patients. 3, 4

The sensation of itch is thought to be mediated by complex signaling pathways which include the dysfunctional epidermal barrier, immune responses, cutaneous sensory nerve fiber activation by pruritogenic molecules such as histamine, neuropeptides and inflammatory cytokines.5 Studies have shown that adults and children with AD suffer from sensory hypersensitivity6, 7 and abnormal sensory responses such as allodynia (triggering of pain sensation from stimuli which do not normally provoke pain), alloknesis (itch evoked by light cutaneous stimuli such as from clothing) and hyperkinesis (excessive itch sensation in response to normal itch-evoking stimuli) that are thought to be attributed to pathological sensory processing pathways.8 There is, however, limited information on the role of cutaneous sensory receptors in the detection and triggering of downstream signaling pathways in response to environmental stimuli.

The olfactory receptor (OR) gene comprises 18 gene families and 300 subfamilies, which code for transmembrane G-protein coupled olfactory receptors on cell surfaces. ORs or smell receptors are mainly located in olfactory sensory neurons in the nasal epithelium, but are also now recognized to be ectopically expressed in non-olfactory tissue such as the airway smooth muscle, kidneys, colonic and vascular epithelium as well as in keratinocytes.9 Fewer than 6% of human ORs have been matched with known ligands.10, 11 The expression and biological functions of ectopic ORs in the skin are poorly characterized. Moreover, their role in inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis are unknown.

The human OR10G7 gene is located on chromosome 11, 11q24.2, a region which contains many OR genes.12 Receptors in this cluster are predicted to be homologous to a murine OR Olfr151, also known as M71.12 Several studies have suggested that the odorant, acetophenone, can function as a ligand for this murine receptor.12–14 A recent study performed a high throughput screening of the human odorant receptors library with a panel of 73 odorants. Acetophenone and eugenol were identified as potential ligands that dose dependently activated human OR10G7.10 Beyond other sources, acetophenone has been suggested to be a metabolic product of phenylalanine transformation by S. aureus; L-phenylalanine is deaminated into trans-cinnamic acid that is later transformed via beta-oxidation into benzoic acid, with acetophenone present as a degradation intermediate in the last transformation15. Since S. aureus colonization is a common feature of AD, acetophenone, as an S. aureus metabolite, may potentially serve as a natural ligand for OR10G7 in the skin. The function of OR10G7, its role in keratinocytes, and effects in AD skin are however not known.

In this study, we aimed to characterize the expression of ORs, in particular OR10G7, in skin biopsies and skin tape strip samples. We also sought to evaluate changes in expression of OR10G7 in primary human keratinocytes from AD patients and normal controls at different stages of differentiation. We further assessed the OR10G7-mediated biological responses of primary human keratinocytes in the presence of its known ligands, the odorants, acetophenone and eugenol.

Methods

Study subjects.

Skin samples were obtained from 30 adult Caucasian subjects with active AD and 25 nonatopic healthy individuals (NC) with no personal and family history of atopy and skin diseases. Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score and eczema area and severity index (EASI) were collected for all AD patients. Patients had not received topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical or oral antibiotics for one week prior to enrollment. Patients had never been treated with systemic immunosuppressive medications. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Jewish Health, Denver, CO.

Skin Tape Strip and Skin Biopsy Collection

Skin tape strip sampling was done for all study participants. In addition, up to two optional 2-mm skin punch biopsies were collected from the non-lesional skin area from the upper extremities. One of the biopsies was dissociated into epidermis and dermis after 1 h of digestion at 37°C in 5 U/ml dispase diluted in PBS (Corning, catalogue # 354235). Isolated epidermis and dermis were immediately submerged into RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and frozen at −80°C for future RNA isolation. The second biopsy was preserved in 10% buffered formalin for immunofluorescent staining.

A total of 20 consecutive D-Squame tape strips (22 mm in diameter, CuDerm, Dallas, Texas) were collected from the volar surface of the forearm. Previous skin biopsy studies of tape-stripped sites had shown that the depth of tape stripping included the upper region of the stratum granulosum, which includes viable cells containing RNA (Kim, Goleva, and Leung, unpublished data). Both nonlesional and lesional skin from patients with AD and skin from healthy control subjects were sampled. On application of the first tape disc, 4 marks were placed around the disc with a pen so that subsequent discs could be applied to the same location. Each tape disc was placed adhesive side up in a separate well of the two 12-well plates allocated for sample collection. Plates were kept on dry ice during tape strip collection. Tape strips 11 through 20 were sequentially scraped into the RLT buffer (Qiagen) and frozen at −80°C. RNeasy Micro Kits (Qiagen) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to isolate RNA from skin tape strips, epidermis, and dermis. The details about the AD and NC studied and sample collection are summarized in the earlier publication by our research group.16

Whole transcriptome sequencing

Skin tape strips and skin biopsies were collected from AD patients and normal controls and RNA samples were prepared as described.16 Twenty one biopsy samples were available from nonlesional AD skin, 9 biopsy samples were available from lesional AD, and 21 biopsy samples were available from healthy controls for RNAseq analysis. In addition, nonlesional skin biopsies from 14 AD patients and 17 healthy controls were available for immunostaining. OR expression was quantified with low input whole transcriptome sequencing of skin tape strips and skin biopsies. In brief, RNA Ampliseq libraries were prepared and barcoded with the Ion Ampliseq™ Transcriptome Human Gene Expression Kit and methods. Barcoded RNA-seq libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Ion Torrent Proton sequencer using P1 chips. The details of analysis have been described by our research group earlier, and the complete RNAseq data have been deposited.16, 17

Fluorescent Immunostaining

OR10G7 and FLG-1 expression in AD non-lesional and NC skin biopsy samples were evaluated by fluorescent immunostaining. Skin sections were blocked with Super Block (ScyTeck Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 5% bovine serum albumin. Slides were then stained with a rabbit polyclonal anti-OR10G7 antibody (1:500 dilution; OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) or a rabbit polyclonal anti-FLG-1 antibody (1:500 dilution, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) or equal amount of rabbit IgG as an isotype control at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline/Tween-20 (0.1%), followed by incubation with a Cy3conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour at room temperature. The slides were visualized with an immunofluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and then coded for unbiased evaluation. Images were captured at 40x magnification, and levels of mean fluorescence intensity were measured with Slidebook 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined for each exposure group and was reported as mean fluorescence intensity±SEM.

RNA preparation and Real time-PCR (RT-PCR)

OR10G7 and FLG-1 mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-PCR in RNA samples prepared from AD and NC biopsies as well as primary human keratinocytes. Total RNA was isolated from skin biopsies and preserved in TRI reagent according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Sigma-Aldrich). RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were used to isolate RNA from human keratinocytes cultures and to further purify RNA prepared from skin biopsies. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript® VILO™ MasterMix according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies). The expression of human 18S, OR10G7, FLG1 and IL-1β in the samples were analyzed by real time RT-PCR using an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as previously described.18 Primers and probes for 18s RNA, OR10G7, FLG-1 and IL-1β were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Primary human keratinocyte cultures.

Primary human keratinocyte lines were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) or isolated from skin biopsies collected from AD and NC subjects. Keratinocyte cultures were grown in EpiLife cell culture medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with human keratinocyte growth supplement S7 (Life Technologies), 0.06 mM CaCl2, and gentamicin/amphotericin. Undifferentiated cells were harvested after 24h of culture. Keratinocytes were induced to differentiate in media containing 1.3 mM CaCl2 for up to 5 days.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) silencing transfection

Primary human keratinocytes were cultured in 225cm2 flasks until confluence and then plated into 10cm cell culture dishes at a concentration of 2.4 × 106 cells per dish for siRNA transfection. Cells were transfected with 20nM of either control nontargeting siRNA or OR10G7 siRNA (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool, Dharmacon, USA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and re-plated the following day into 96-well plates for the ATP assays.

ATP Assay

Acetophenone (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and eugenol (Acros Organics, New Jersey, USA) were solubilized in absolute ethanol. Serial dilutions of each odorant (10-fold dilutions from 1mM to 0.001µM) were prepared fresh in EpiLife® media immediately before each experiment. Primary human keratinocytes were cultured in 96-well plates for 1 day and then incubated with the serial concentrations of acetophenone, eugenol or media alone (control) for 2 minutes at room temperature. The supernatants were collected and transferred to a separate 96-well plate. The ATP concentrations in the supernatants were measured using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An ATP standard curve was generated to correlate luminescence signals with ATP concentrations. The relative luminescence was measured with the DTX 880 Multimode Detector and analyzed using Softmax Pro (v 6.2.2), Molecular Devices, LLC.

Western Blot

Primary human keratinocytes were grown in 10cm cell culture dishes at a concentration of 2.4 × 106 cells per dish and then transfected with control or OR10G7 siRNA. Cells were harvested in 1 ml of lysis buffer (Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail, PMSF 200 mM, Na-orthovanadate, 100mM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, USA). 400 µl of each protein lysate was centrifuged in speed vacuum centrifuge for 1.5 hours to produce a concentrated 50 µl lysate that was used for Western blot analysis. OR10G7 primary antibody (LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc, USA) was used at a concentration of 1:100. ECL™ anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase linked F(ab)2 fragment secondary antibody (GE Healthcare UK Ltd) was used at a concentration of 1:2000. Beta actin (1:2000) was used as a control. Imaging was performed using the ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System, BioRad.

Cyclic AMP (cAMP) Assay

Primary human keratinocytes were transfected with control or OR10G7 siRNA as described above. Keratinocytes were then replated into 96-well plates for 1 day and then incubated with the serial concentrations of acetophenone, eugenol or media alone (control) for 30 minutes at room temperature as described above. cAMP concentrations in the supernatants were measured using the Cyclic AMP XP® Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and fluorescence units (FLU) were recorded using a luminometer after 30 minutes of incubation. The Cyclic AMP XP® Assay Kit is a competition enzyme-linked immunoassay used to determine cAMP levels in cells or tissues of interest. Because of the competitive nature of this assay, the magnitude of the absorbance is inversely proportional to the quantity of sample cAMP. A cAMP standard curve was generated to correlate absorbance signals with cAMP concentrations. The relative absorbance was measured with the DTX 880 Multimode Detector and analyzed using Softmax Pro (v 6.2.2), Molecular Devices, LLC.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Primary human keratinocytes were cultured in 96-well plates for 1 day and then incubated with the serial concentrations of acetophenone, eugenol or media alone (control) for 24h. The supernatants were collected and transferred to a separate 96-well plate. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the supernatants was measured using the CytoTox-ONE™ Homogenous Membrane Integrity Assay (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysis solution was used as provided by the manufacturer as a positive 100% cell lysis control. The relative luminescence was measured with the DTX 880 Multimode Detector and analyzed using Softmax Pro (v 6.2.2), Molecular Devices, LLC.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student t-test was used to determine the significance of difference between two experimental groups. All data were expressed as mean±SEM unless otherwise stated. Differences with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Whole transcriptome sequencing

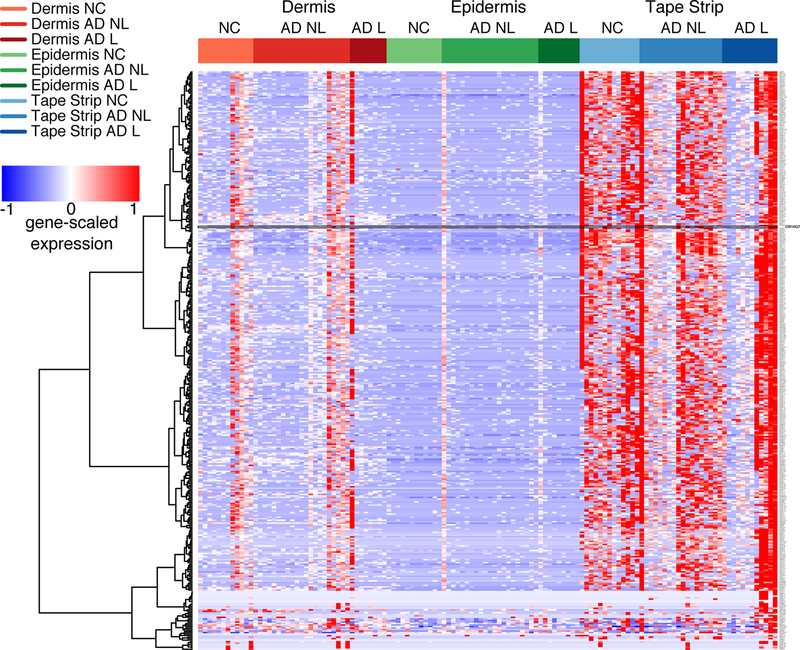

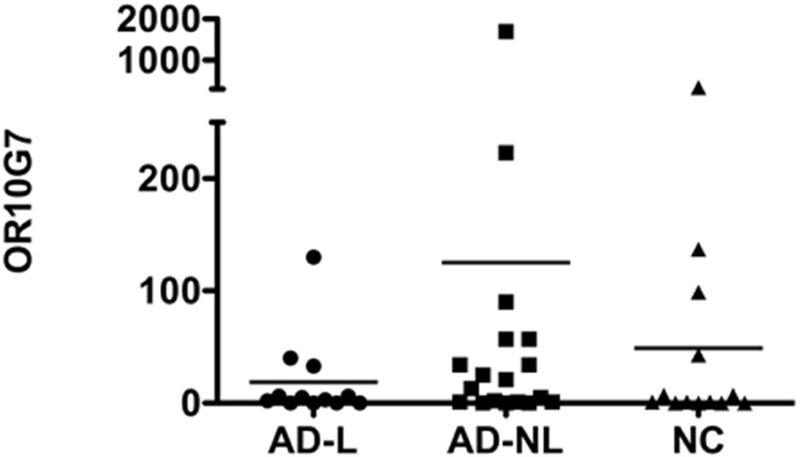

To evaluate the location and relative expression of ORs in AD and normal skin, low input whole transcriptome sequencing was performed on skin tape strip and skin biopsy specimens obtained from AD and NC subjects. The heat map in Figure 1A (the high resolution magnifiable figure is also included as Supplementary Figure 1 in the electronic online repository) shows the relative expression of ORs in the dermis, epidermis and skin tape strip samples of AD and NC subjects. The Ampliseq method detected a total of 381 OR gene transcripts in the skin samples, with the greatest OR expression detected in the skin tape strips, corresponding to the upper granular layer of the skin. OR10G7 was selected for the functional analysis, as this receptor was detectable in nonlesional skin tape strips of 12 out 18 AD patients, and was only present in skin tape strips of 4 out 13 healthy controls tested (p<0.05) (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the agonists for the majority of the olfactory receptors are not known. To our advantage, acetophenone and eugenol had previously been predicted as odorant ligands for OR10G7 receptor10, but no studies on their role in AD have been performed to date. Acetophenone has been also reported to be a metabolite produced by S. aureus, a common AD skin colonizing bacteria15. Eugenol is present in many household products and its derivative, isoeugenol, is an irritant and is included as a component of the T.R.U.E. Test for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. Following these considerations, we thus focused on assessing the biological mechanisms through which this OR modulated chemosensory responses to these odorants.

Figure 1. Olfactory receptor expression in the skin of AD and NC subjects.

A) Heatmap showing OR expression in dermis, epidermis and tape strip samples from AD patients (L=lesional, NL=non-lesional) and normal controls (NC). The highest expression of olfactory receptors was found in skin tape strip samples. The expression of OR10G7 receptor followed in this manuscript is outlined on the heatmap. B) Expression of OR10G7 mRNA in skin tape strip samples of AD patients and healthy controls as detected by RNAseq analysis.

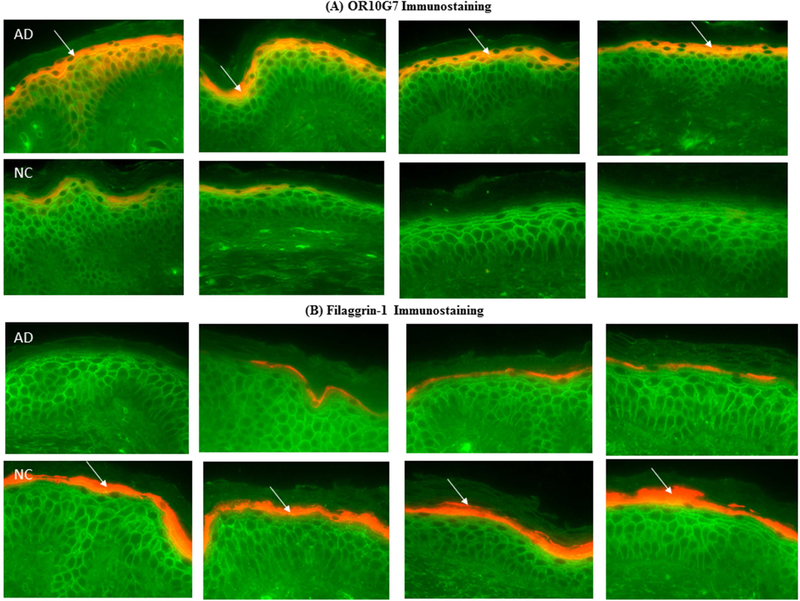

Immunostaining for OR10G7 and Filaggrin-1 (FLG-1)

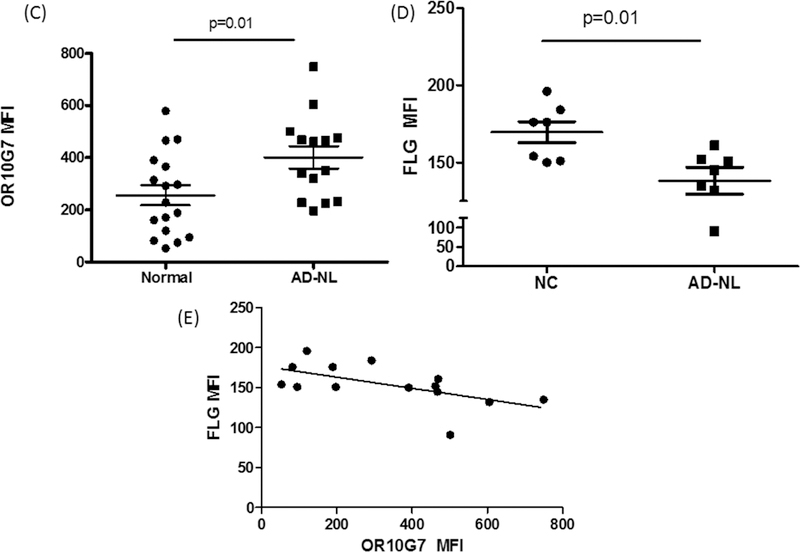

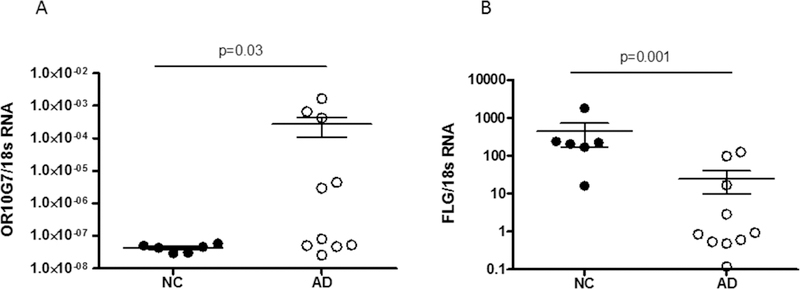

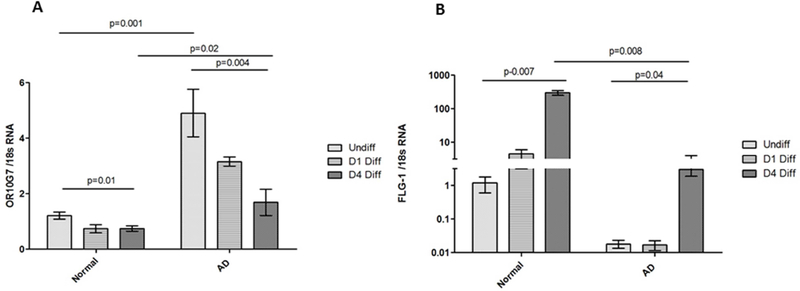

To confirm the protein localization of OR10G7 and FLG-1 in the skin samples, fluorescent immunostaining was performed on skin biopsies from AD and NC subjects (Figure 2A and B). Staining of the OR, OR10G7, was predominantly observed in the upper granular layer of the epidermis (Figure 2A) and was more prominent and continuous in AD non-lesional skin biopsies as compared to NC skin biopsies, where staining was patchy. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of OR10G7 staining was also significantly higher in the AD non-lesional skin biopsies compared to NC skin biopsies (401.6 ± 42.9 vs 255.7 ± 38.5, p=0.01) (Figure 2C). This corresponded to lower FLG-1 MFI (138.1 ± 8.7 vs 169.6 ± 6.8, p=0.01) (Figure 2D) in matched AD versus NC skin biopsies. The inverse correlation between OR10G7 and FLG-1 MFI in AD and NC skin biopsies is shown in Figure 2E, Spearman r = −0.66 (95% CI −0.89 to −0.18), p=0.009. Likewise, OR10G7 mRNA expression was also higher in AD skin biopsies than in NC subjects (2.7× 10−4 ± 1.7×10−4 vs 4.3 10−8 ± 4.6×10−9, ng OR10G7/ng 18s RNA, p=0.03) (Figure 3A), with reduced FLG-1 mRNA expression (24.92 ± 47.1 vs 447.5 ± 680.2, ng FLG-1/ng 18s RNA, p=0.001) (Figure 3B) in AD non-lesional skin compared to NC skin biopsies.

Figure 2. OR10G7 and FLG-1 immunostaining in AD and NC skin biopsies.

A) OR10G7 and B) FLG-1 expression in matched skin biopsies of normal controls (NC) and AD patients are shown by arrows. OR10G7/FLG-1 – cy3, red. Wheat germ agglutinin (FITC, green) was used to counter stain cell membranes. Magnification 200x.

A) OR10G7 staining is observed exclusively in the upper granular layer of the epidermis. Note the prominent staining of OR10G7 in AD skin biopsies and corresponding patchy staining in NC skin. B) There is corresponding reduced FLG-1 expression in AD skin biopsies compared to NC skin. Expression of C) OR10G7 and D) FLG-1 are compared using mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

E) Scatterplot shows the inverse correlation between OR10G7 and FLG-1 MFI. Spearman r = −0.66 (95% CI −0.89 to −0.18), p=0.009

Figure 3. OR10G7 and FLG-1 mRNA expression in skin biopsies of NC and AD subjects.

A) OR10G7 mRNA and B) FLG-1 mRNA expression were measured by real time PCR (RTPCR) in AD non-lesional (AD) and normal control (NC) skin biopsies. There is increased OR10G7 mRNA expression in AD non-lesional skin compared to NC skin (p=0.03), with corresponding reduced FLG-1 mRNA expression in AD non-lesional skin compared to NC skin (p=0.001). A two-tailed t-test was used for significance testing. Data are shown as the mean ± SD.

OR10G7 expression in primary human keratinocytes

To evaluate the relative expression of OR10G7 at various stages of keratinocyte differentiation, we assessed the expression of OR10G7 mRNA using RT-PCR in primary human keratinocytes cultured from skin biopsies of AD and NC subjects. OR10G7 expression was highest in undifferentiated keratinocytes compared to 1 day and 4-day calcium-differentiated primary human keratinocytes in both AD and NC cell lines (p<0.05). More importantly, the expression of OR10G7 decreased with progressive differentiation but remained significantly higher in AD keratinocytes compared to NC cell lines (Figure 4A). This corresponded to a significantly lower expression of Filaggrin-1 mRNA in AD compared to NC keratinocytes at all stages of differentiation (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. OR10G7 and FLG-1 mRNA expression in undifferentiated, 1 day and 4 day Ca2+ differentiated primary human keratinocytes from NC and AD patients.

Primary human keratinocytes from NC and AD patients were grown in culture and harvested in the undifferentiated state, Day 1 and Day 4 post 1.3mM CaCl2 differentiation. OR10G7 (A) and FLG-1 (B) mRNA expression in undifferentiated and differentiated keratinocytes is shown. OR10G7 mRNA expression is higher in AD than NC keratinocytes at all stages of Ca2+ differentiation (p<0.05). OR10G7 expression is also down-regulated with progressive Ca2+ differentiation in both AD and NC keratinocytes (p<0.05). FLG-1 mRNA expression was lower in AD than NC keratinocytes at all stages of Ca2+ differentiation, particularly on Day 4 post differentiation (p<0.05). Each condition was performed in triplicate, n=3 experiments. A two-tailed t-test was used for significance testing. Data are shown as the mean ± SD.

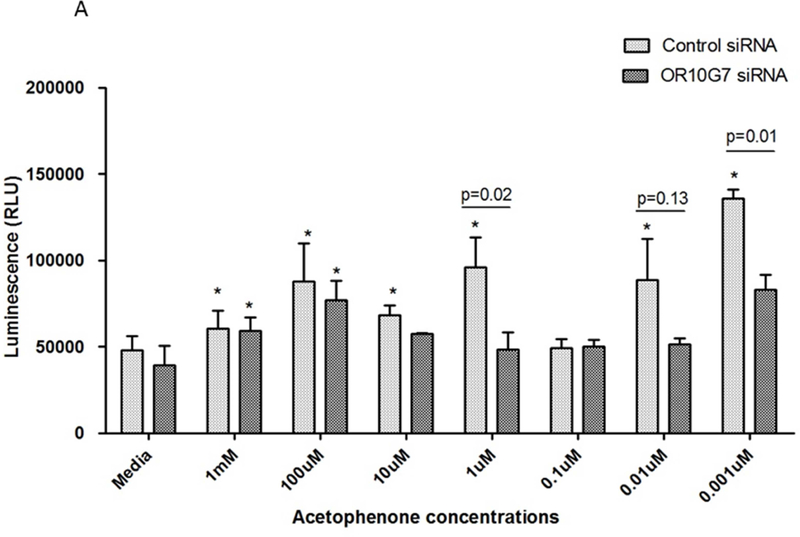

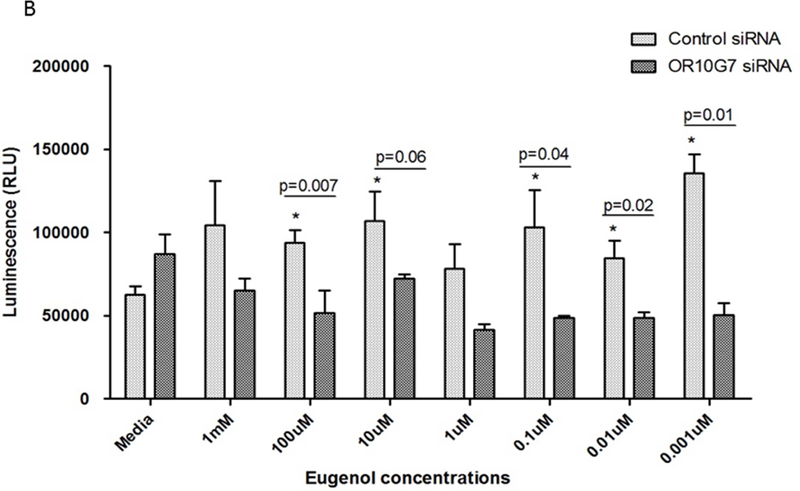

OR10G7-mediated ATP responses to odorant stimulation

To investigate the effect of odorant stimulation on keratinocytes, serial dilutions of acetophenone and eugenol from 1mM to 0.001µM were added to undifferentiated human keratinocytes in culture. Exposure of olfactory epithelium to odorants results in the activation of ORs and this induces cellular ATP production through activation of the adenylyl cyclase-ATPc-AMP pathway.19 We thus measured ATP production as an indicator of activation of this pathway in keratinocytes using the CellTiter-Glo® Assay. Luminescence units (RLU) were recorded using a luminometer after 2 min incubation with odorants. The addition of acetophenone and eugenol significantly stimulated ATP release from keratinocytes (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5. ATP production in Control or OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes treated with acetophenone or eugenol.

Control or OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes were treated with either media (control) or varying concentrations of A) acetophenone or B) eugenol. Production of ATP was measured using the CellTiter-Glo® Assay and luminescence units (RLU) recorded using a luminometer after 2 minutes incubation.

P values specified explicitly in the figure are comparing control siRNA vs OR10G7 siRNA-treated cells for any given dose of acetophenone/eugenol.

*represents p values that are statistically significant (p<0.05) with reference to the non-odorant treated cells (control)

Each condition was performed in triplicate, n=3 experiments. A two-tailed t test was used for significance testing. Data are shown as the mean ± SD.

To verify the role of OR10G7 in modulating ATP responses to odorants, we transfected control or OR10G7 siRNA into primary keratinocytes and treated them with serial dilutions of acetophenone and eugenol or media alone. The knockdown of OR10G7 in OR10G7 siRNA-transfected cells was confirmed by Western blot (Supplementary Figure 2A and 2B). Cells which had been transfected by OR10G7 siRNA no longer demonstrated an increased ATP production in response to odorant stimulation compared to media-treated cells, suggesting that odorant-induced ATP production is dependent upon OR10G7 (Figure 5A and B).

OR10G7-mediated cyclic AMP (cAMP) production was also measured in control and OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes to validate the ATP response to the odorants. Control or OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes were treated with either media (control) or varying concentrations of acetophenone or eugenol as shown in Supplementary Figure 3. cAMP production was measured using the Cyclic AMP XP® Assay Kit and fluorescence units (FLU) were recorded using a luminometer after 30 minutes of incubation. Increased cAMP production was observed in control siRNA transfected keratinocytes treated with 100µM of eugenol (p=0.004). However, this response was abolished in OR10G7 siRNA transfected cells treated with the same concentration of eugenol. This effect was not observed to the same extent in acetophenone-treated keratinocytes, indicating that the cAMP assay is likely less sensitive than the ATP assay in detecting keratinocyte responses to acetophenone (Figure 5A).

We also confirmed the absence of any odorant-induced cell toxicity using a cytotoxicity assay (CytoTox-ONE™ Homogenous Membrane Integrity Assay (Promega)) (Supplementary Figure 4).

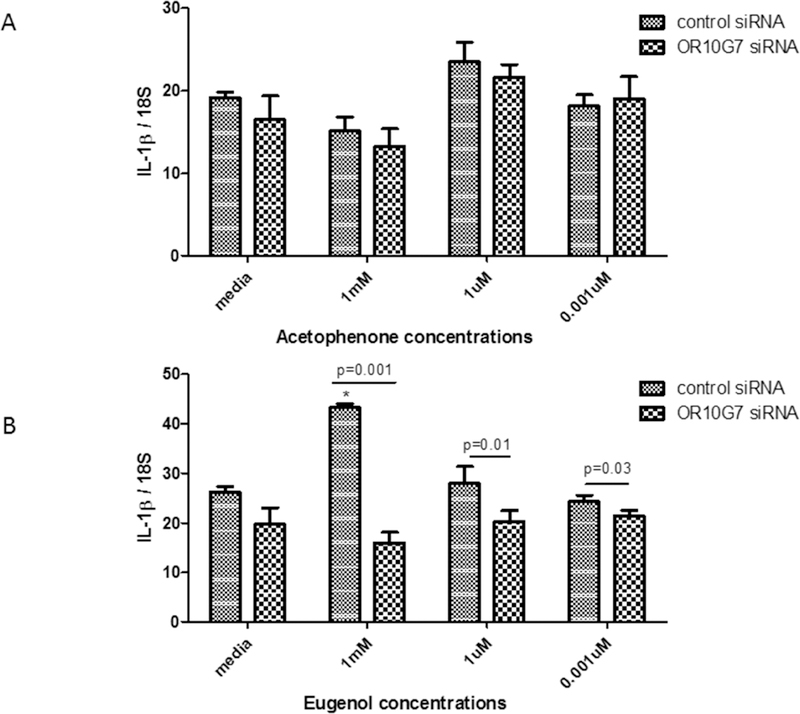

OR10G7-mediated inflammatory response to odorants

Primary human keratinocytes were transfected with control or OR10G7 siRNA and treated with serial dilutions of acetophenone and eugenol or media alone. The expression of IL1β mRNA was increased in control siRNA and eugenol treated keratinocytes, but was downregulated in OR10G7 siRNA and eugenol-treated keratinocytes (Figure 6A and B) (p<0.05). While there was a trend towards downregulation of IL-1β mRNA in OR10G7 siRNA and acetophenone-treated keratinocytes, this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 6. IL-1β mRNA expression in Control or OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes treated with acetophenone or eugenol.

Control or OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes were treated with either media (control) or varying concentrations of A) acetophenone or B) eugenol and IL-1β mRNA expression measured using RT-PCR. A two-tailed t test was used for significance testing. Data are shown as the mean ± SD.

* Represents p=0.004 comparing ATP production in control siRNA-treated keratinocytes treated with eugenol to control siRNA-treated keratinocytes treated with media alone.

Discussion

Conventional nasal olfaction is mediated through ORs which are found on olfactory epithelium located on the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons in the nasal cavity.19 ORs are also expressed ectopically in non-olfactory tissues such as the gut, skeletal muscle, testes, brain and skin where they may perform additional physiological functions apart from olfaction.20 Transcriptomic data from this study showed that 381 OR gene transcripts were detected in the dermis, epidermis and skin tape strip samples of AD and NC subjects, predominantly in the skin tape strip samples, which correspond to the upper granular layer of the epidermis. In particular, we found that a novel OR, OR10G7, was expressed at significantly higher levels in AD compared to NC skin biopsies. This finding was corroborated by a significantly increased expression of OR10G7 in cultured AD primary human keratinocytes compared to NC keratinocytes. We also found that OR10G7 expression was highest in keratinocytes in the undifferentiated state and their expression was downregulated with progressive differentiation. This correlated with reduced expression of FLG-1 in matched AD skin biopsies as compared with NC skin biopsies as well as in primary human keratinocytes.

It is known that AD skin is characterized by abnormal keratinocyte terminal differentiation, with delayed and discontinuous expression of terminal differentiation proteins such as corneodesmosin, filaggrin, involucrin and loricrin, compared to normal skin.21 Even in the upper granular layer, where normal keratinocytes are terminally differentiated, AD keratinocytes do not undergo terminal differentiation but are instead held in a state of incomplete differentiation. Our above findings are consistent with this concept. The differential expression of OR10G7 observed in AD versus normal skin may thus be a result of inhibition of keratinocyte terminal differentiation in AD. Due to increased expression, this OR may play a more significant role in modulating sensory pathways in AD skin. There is, however, very limited information on the role of olfactory receptor ligands in the pathogenesis of AD.

In the nose, the process of olfaction begins with the binding of volatile odorant molecules to G-protein coupled ORs located on the olfactory epithelium. Activation of these ORs stimulate adenylyl cyclase, increasing the production of ATP and its conversion to cAMP, which in turn triggers the influx of Ca2+ through cyclic nucleotide-gated channels and generates an action potential which is transmitted to the central nervous system.19

In this study, we found that ORs ectopically expressed in keratinocytes also activate adenylyl cyclase-ATP-cAMP dependent signaling pathways in response to odorant stimulation. It is known that multiple sensory neurons are located in close proximity to, and communicate with, keratinocytes in the epidermis.22 This results in the transmission of sensory impulses to the central nervous system.23, 24 This mechanism is implicated in nociceptive pathways through which keratinocytes mediate chemosensory perception.22, 25

Exposure to heat26, hypo-osmotic shock27, mechanical damage28, air 29 as well as contact sensitizers30 have been shown to trigger ATP release from keratinocytes.22, 26, 29 Mihara et al. demonstrated that heat, chemical and mechanical stimuli triggered ATP release from mouse oesophageal keratinocytes through the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4).31ATP activates purinergic receptors in the skin, inducing the release of secondary transmitters such as calcium and inflammatory cytokines in response to innocuous and noxious stimuli.32–34 More specifically, it activates members of the Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor (MRGPR) family35 as well as TRPV1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1)36, 37 which are expressed in cutaneous sensory neurons that mediate responses to itch and pain. ATP production is also a prerequisite for the development of contact hypersensitivity 38 as well as allergic responses. 39

Acetophenone and eugenol are common ingredients found in cosmetics and household products, many of which are applied onto or come into close contact with the skin and have been implicated as allergens capable of inducing contact sensitization and type 1 hypersensitivity reactions40–44. Acetophenone is an aromatic ketone used as a fragrance ingredient in soap detergents and perfumes and food flavorings.45 Beyond other sources, acetophenone has been suggested to be a metabolic product of phenylalanine transformation by S. aureus, which frequently colonizes AD skin.15 Acetophenone, as one of the S. aureus metabolites, can be one of the natural triggers of OR10G7 receptor in AD skin. Eugenol is a phenylpropene compound derived from plant sources such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon and bay leaf. Eugenol and its derivative isoeugenol are commonly found in perfumes, flavorings and essential oils, and are also used as local antiseptics or anesthetics and in prosthodontic applications in dentistry. Eugenol and isoeugenol have been classified as weak46 and moderate47 skin sensitizers respectively. The incidence of isoeugenol sensitization was as high as 2.5% in a cohort of patients diagnosed with allergic contact dermatitis.43 Eugenol was also one of the top 4 fragrance allergens identified in a cohort of patients with hand eczema48. In 1998, the International Fragrance Association recommended that the upper limit of isoeugenol concentrations in cosmetic products be reduced from 0.2% to 0.02% in light of the increasing incidence of isoeugenol-induced allergic contact dermatitis.49

Eugenol-treated primary human keratinocytes transfected with control siRNA induced increased expression of IL-1β mRNA, which was abolished in OR10G7 siRNA transfected keratinocytes, demonstrating the role of OR10G7 in inducing inflammatory responses such as IL-1β production in response to eugenol. This was observed to a lesser, non-significant, extent in acetophenone-treated cells. Likewise, the cAMP assay was less sensitive than the ATP assay in detecting a significant difference in acetophenone-treated cells transfected with either control or OR10G7 siRNA. This suggests that eugenol is likely a better agonist for the OR10G7 receptor and a stronger inducer of inflammatory responses compared to acetophenone.

In summary we have demonstrated for the first time that the ectopic OR, OR10G7, is detectable in the skin, is more highly expressed in AD compared to normal skin and is inversely correlated with FLG-1 expression. AD patients suffer from abnormal sensory processing such as a heightened perception of pain or itch in response to ordinarily non-noxious environmental stimuli, which is known as allodynia or hyperknesis.6, 50 The increased expression of OR10G7 in AD skin and its demonstrated role in triggering ATP-dependent responses to odorant allergens suggest that this OR may be involved in the pathogenesis of allergic inflammation and/or induction of chemosensory pathways mediating itch or pain perception. Thus, ORs may serve as potential future therapeutic targets for the inhibition of pathological pain or itch pathways in allergic inflammatory skin disorders such as AD. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which ORs may perform this functional role.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

Ectopic olfactory receptors (OR) are expressed in the skin, particularly in the upper granular layer.

The ectopic OR - OR10G7 was significantly more highly expressed in AD compared to normal control skin biopsies.

OR10G7 mediated the production of ATP, an essential neurotransmitter in sensory pathways, in response to acetophenone and eugenol odorant stimulation, highlighting its possible role in chemosensory signal transduction, particularly in AD skin.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

Tham EH is supported by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Research Training Fellowship grant [MH 095:003\008–225] from the National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore. This work was supported by NIH grants 1U19AI117673, R01AR41256 and UL1RR025780, and The Edelstein Family Chair of Pediatric Allergy.

Abbreviations

- AD

Atopic Dermatitis

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- NC

Normal Control

- OR

Olfactory Receptor

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- RT-PCR

Real time – polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement:

All authors have no potential conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2014;134(4):769–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung DY. New insights into atopic dermatitis: role of skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology 2013;62(2):151–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blome C, Radtke MA, Eissing L, Augustin M. Quality of Life in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: Disease Burden, Measurement, and Treatment Benefit. American journal of clinical dermatology 2016;17(2):163–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filanovsky MG, Pootongkam S, Tamburro JE, Smith MC, Ganocy SJ, Nedorost ST. The Financial and Emotional Impact of Atopic Dermatitis on Children and Their Families. The Journal of pediatrics 2016;169:284–90.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollanazar NK, Smith PK, Yosipovitch G. Mediators of Chronic Pruritus in Atopic Dermatitis: Getting the Itch Out? Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology 2016;51(3):263–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel-Yeger B, Mimouni D, Rozenman D, Shani-Adir A. Sensory processing patterns of adults with atopic dermatitis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 2011;25(2):152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, Patel KR, Singam V, Patel N, et al. Burden of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 2017;119(6):548–52.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen HH, Akiyama T, Nattkemper LA, van Laarhoven A, Elberling J, Yosipovitch G, et al. Alloknesis and hyperknesis-mechanisms, assessment methodology, and clinical implications of itch sensitization. Pain 2018;159(7):1185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Zhao H, Fu N, Chen L. The diversified function and potential therapy of ectopic olfactory receptors in non-olfactory tissues. Journal of cellular physiology 2018;233(3):2104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mainland JD, Keller A, Li YR, Zhou T, Trimmer C, Snyder LL, et al. The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire. Nature neuroscience 2014;17(1):114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trimmer C, Snyder LL, Mainland JD. High-throughput analysis of mammalian olfactory receptors: measurement of receptor activation via luciferase activity. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 2014(88). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malnic B, Godfrey PA, Buck LB. The human olfactory receptor gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(8):2584–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleischmann A, Shykind BM, Sosulski DL, Franks KM, Glinka ME, Mei DF, et al. Mice with a “monoclonal nose”: perturbations in an olfactory map impair odor discrimination. Neuron 2008;60(6):1068–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von der Weid B, Rossier D, Lindup M, Tuberosa J, Widmer A, Col JD, et al. Large-scale transcriptional profiling of chemosensory neurons identifies receptor-ligand pairs in vivo. Nat Neurosci 2015;18(10):1455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipiak W, Sponring A, Baur MM, Filipiak A, Ager C, Wiesenhofer H, et al. Molecular analysis of volatile metabolites released specifically by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol 2012;12:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyjack N, Goleva E, Rios C, Kim BE, Bin L, Taylor P, et al. Minimally invasive skin tape strip RNA sequencing identifies novel characteristics of the type 2-high atopic dermatitis disease endotype. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2018;141(4):1298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berdyshev E, Goleva E, Bronova I, Dyjack N, Rios C, Jung J, et al. Lipid abnormalities in atopic skin are driven by type 2 cytokines. JCI insight 2018;3(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura I, Gao B, Boguniewicz M, Darst MA, Travers JB, Leung DY. Distinct patterns of gene expression in the skin lesions of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: a gene microarray analysis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2003;112(6):1195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antunes G, Simoes de Souza FM. Olfactory receptor signaling. Methods in cell biology 2016;132:127–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang N, Koo J. Olfactory receptors in non-chemosensory tissues. BMB reports 2012;45(11):612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle SJ, Shemer A, Chiricozzi A, Nograles K, Cardinale I, et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2011;127(4):954–64.e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sondersorg AC, Busse D, Kyereme J, Rothermel M, Neufang G, Gisselmann G, et al. Chemosensory information processing between keratinocytes and trigeminal neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry 2014;289(25):17529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai T, Veitinger S, Peek I, Busse D, Eckardt J, Vladimirova D, et al. Two olfactory receptorsOR2A4/7 and OR51B5-differentially affect epidermal proliferation and differentiation. Experimental dermatology 2017;26(1):58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busse D, Kudella P, Gruning NM, Gisselmann G, Stander S, Luger T, et al. A synthetic sandalwood odorant induces wound-healing processes in human keratinocytes via the olfactory receptor OR2AT4. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2014;134(11):2823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumbauer KM, DeBerry JJ, Adelman PC, Miller RH, Hachisuka J, Lee KH, et al. Keratinocytes can modulate and directly initiate nociceptive responses. eLife 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandadi S, Sokabe T, Shibasaki K, Katanosaka K, Mizuno A, Moqrich A, et al. TRPV3 in keratinocytes transmits temperature information to sensory neurons via ATP. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 2009;458(6):1093–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azorin N, Raoux M, Rodat-Despoix L, Merrot T, Delmas P, Crest M. ATP signalling is crucial for the response of human keratinocytes to mechanical stimulation by hypo-osmotic shock. Experimental dermatology 2011;20(5):401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsutsumi M, Inoue K, Denda S, Ikeyama K, Goto M, Denda M. Mechanical-stimulation-evoked calcium waves in proliferating and differentiated human keratinocytes. Cell and tissue research 2009;338(1):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barr TP, Albrecht PJ, Hou Q, Mongin AA, Strichartz GR, Rice FL. Air-stimulated ATP release from keratinocytes occurs through connexin hemichannels. PloS one 2013;8(2):e56744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onami K, Kimura Y, Ito Y, Yamauchi T, Yamasaki K, Aiba S. Nonmetal haptens induce ATP release from keratinocytes through opening of pannexin hemichannels by reactive oxygen species. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2014;134(7):1951–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mihara H, Boudaka A, Sugiyama T, Moriyama Y, Tominaga M. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)-dependent calcium influx and ATP release in mouse oesophageal keratinocytes. The Journal of physiology 2011;589(Pt 14):3471–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue K, Hosoi J, Denda M. Extracellular ATP has stimulatory effects on the expression and release of IL-6 via purinergic receptors in normal human epidermal keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2007;127(2):362–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moehring F, Cowie AM, Menzel AD, Weyer AD, Grzybowski M, Arzua T, et al. Keratinocytes mediate innocuous and noxious touch via ATP-P2X4 signaling. eLife 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegg CC, Greenwood D, Huang W, Han P, Lucero MT. Activation of purinergic receptor subtypes modulates odor sensitivity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2003;23(23):8291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dussor G, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, McCleskey EW. Cutaneous sensory neurons expressing the Mrgprd receptor sense extracellular ATP and are putative nociceptors. Journal of neurophysiology 2008;99(4):1581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997;389(6653):816–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim S, Barry DM, Liu XY, Yin S, Munanairi A, Meng QT, et al. Facilitation of TRPV4 by TRPV1 is required for itch transmission in some sensory neuron populations. Science signaling 2016;9(437):ra71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber FC, Esser PR, Muller T, Ganesan J, Pellegatti P, Simon MM, et al. Lack of the purinergic receptor P2X(7) results in resistance to contact hypersensitivity. The Journal of experimental medicine 2010;207(12):2609–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kouzaki H, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, O’Grady SM, Kita H. The danger signal, extracellular ATP, is a sensor for an airborne allergen and triggers IL-33 release and innate Th2-type responses. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2011;186(7):4375–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raison-Peyron N, Bergendorff O, Bourrain JL, Bruze M. Acetophenone azine: a new allergen responsible for severe contact dermatitis from shin pads. Contact dermatitis 2016;75(2):106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnuch A, Uter W, Geier J, Lessmann H, Frosch PJ. Sensitization to 26 fragrances to be labelled according to current European regulation. Results of the IVDK and review of the literature. Contact dermatitis 2007;57(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barratt MD, Basketter DA. Possible origin of the skin sensitization potential of isoeugenol and related compounds. (I). Preliminary studies of potential reaction mechanisms. Contact dermatitis 1992;27(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White JM, White IR, Glendinning A, Fleming J, Jefferies D, Basketter DA, et al. Frequency of allergic contact dermatitis to isoeugenol is increasing: a review of 3636 patients tested from 2001 to 2005. The British journal of dermatology 2007;157(3):580–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tammannavar P, Pushpalatha C, Jain S, Sowmya SV. An unexpected positive hypersensitive reaction to eugenol. BMJ case reports 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weyrich LS, Dixit S, Farrer AG, Cooper AJ, Cooper AJ. The skin microbiome: Associations between altered microbial communities and disease. The Australasian journal of dermatology 2015;56(4):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Api AM, Belsito D, Bhatia S, Bruze M, Calow P, Dagli ML, et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, Eugenol, CAS Registry Number 97–53-0. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2016;97s:S25–s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Api AM, Belsito D, Bhatia S, Bruze M, Calow P, Dagli ML, et al. RIFM fragrance ingredient safety assessment, isoeugenol, CAS Registry Number 97–54-1. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2016;97s:S49–s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heydorn S, Johansen JD, Andersen KE, Bruze M, Svedman C, White IR, et al. Fragrance allergy in patients with hand eczema - a clinical study. Contact dermatitis 2003;48(6):317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White IR, Johansen JD, Arnau EG, Lepoittevin JP, Rastogi S, Bruze M, et al. Isoeugenol is an important contact allergen: can it be safely replaced with isoeugenyl acetate? Contact dermatitis 1999;41(5):272–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engel-Yeger B, Habib-Mazawi S, Parush S, Rozenman D, Kessel A, Shani-Adir A. The sensory profile of children with atopic dermatitis as determined by the sensory profile questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2007;57(4):610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.