Abstract

Objectives:

Bipolar disorders (BD) are characterized by emotion and cognitive dysregulation. Mapping deficits in the neurocircuitry of cognitive-affective regulation allows for potential identification of intervention targets. The current study used functional MRI data in BD patients and healthy controls during performance on a task requiring cognitive and inhibitory control superimposed on affective images, assessing cognitive and affective interference.

Methods:

Functional MRI data were collected from 39 BD patients and 36 healthy controls during performance on the Multi-Source Interference Task overlaid on images from the International Affective Picture System (MSIT-IAPS). Analyses examined patterns of activation in a priori regions implicated in cognitive and emotional processing. Functional connectivity to the anterior insula during task performance was also examined, given this region’s role in emotion-cognition integration.

Results:

BD patients showed significantly less activation during cognitive interference trials in inferior parietal lobule, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, mid-cingulate, and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex regardless of affective valence. BD patients showed deviations in functional connectivity with anterior insula in regions of the default mode and frontoparietal control networks during negatively valenced cognitive interference trials.

Conclusions:

Our findings show disruptions in cognitive regulation and inhibitory control in BD patients in the presence of irrelevant affective distractors. Results of this study suggest one pathway to dysregulation in BD is through inefficient integration of affective and cognitive information, and highlight the importance of developing interventions that target emotion-cognition integration in BD.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, fMRI, emotion regulation, cognition, Multi Source Interference Task

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a debilitating illness that often leads to chronic functional impairment and subsequent poor quality of life. Individuals diagnosed with BD struggle with affect lability,1–5 emotion dysregulation,6–9 cognitive dysfunction,10–15 and behavioral impulsivity.16–19 Whereas emotion dysregulation and cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder have been relatively well studied,20–26 the interaction of these two areas of functional impairment is less well understood, as is the relation to behavioral impulsivity. The ability to adaptively integrate affective and cognitive information and modulate behavior accordingly is a crucial aspect of healthy functioning. Understanding deficits in the interaction of emotion, cognition and behavior in BD patients relative to healthy individuals at the level of neurocircuitry provides important clues to the pathophysiology of BD, with the potential for delineating viable targets for rehabilitative intervention.

The simultaneous processing of cognitive and affective information for behavioral response selection has been shown to recruit distributed networks of cortical regions including dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), supplemental motor area (SMA), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), insula and regions of the parietal cortex.27–31 The dACC and anterior insula, extending to the VLPFC (fronto-insular pole), represent key regions within the salience network implicated in monitoring, detecting and regulating salience signaling from limbic and striatal areas.32 The DLPFC, dmPFC, rostral VLPFC and superior and inferior parietal lobule (SPL, IPL) represent key regions within the fronto-parietal executive control network implicated in the regulation of attention towards or away from salient cues and the maintenance of goal-directed behavior and response selection.33, 34 Cognition-emotion integration requires the dynamic coordination and flexible switching between these functional networks.35 A growing literature has identified the anterior insula as a key structure modulating switching between functional networks in service of regulatory goals.36–38 Examining responses along this broader neurocircuitry in BD patients and the functional connectivity of these network regions to the anterior insula during the simultaneous processing of cognitive and affective information could provide clues to sources of regulatory dysfunction in BD.

Only a handful of studies to date have explicitly examined the integration of cognitive and affective processing in BD. These studies implicate disruptions in broader fronto-parietal and fronto-striatal networks in BD patients relative to controls.39–41 For example, using an emotional Stroop task, in which participants must indicate the ink color of emotional words, Lagopoulus et al40 found healthy controls primarily recruited fronto-parietal control regions including DLPFC and IPL to complete the task, whereas BD patients primarily recruited subcortical limbic regions including amygdala, hippocampus and regions of the caudate. This suggests greater regulatory control during task performance in healthy controls versus greater processing of affective salience in BD patients. Using a similar emotional Stroop task, Mahli et al41 found significantly weaker fronto-striatal recruitment in BD patients relative to controls, including weaker VLPFC, thalamus, caudate and putamen activation, suggestive of weaker regulatory control of behavioral response selection. BD patients were also significantly slower to respond to stimuli, suggesting impaired attentional control. In a more recent study, Favre et al39 used a modified emotional Stroop task that superimposes emotion words (happy, fear) on images showing happy or fearful facial expressions.42 BD patients evidenced significantly reduced DLPFC activation and slower reaction time in response to word and facial expression incongruence relative to healthy controls. Further, functional connectivity analyses showed significantly stronger positive correlations between DLPFC and default mode network regions (DMN; subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex) in BD patients during incongruence, in contrast to significantly stronger negative DLPFC-DMN functional correlations in healthy controls, suggesting BD patients may have greater difficulty switching from internally focused processing to task-related processing in the presence of competing cognitive-affective demands. Collectively, these studies suggest BD patients exhibit reduced regulatory control and increased salience processing during cognitive tasks that involve the simultaneous processing of affective information.

In the current study, we sought to add to the existing literature on cognitive and emotion integration in BD by examining the ability to engage in a complex cognitive task and modulate behavior accordingly while simultaneously screening out distracting and irrelevant affective information, a process that is crucial for adaptive regulation. In this design, participants are not asked to engage directly with affective stimuli, but instead affective stimuli serve as a background distractor. This is relevant to clinical presentations of BD, wherein patients struggle to override affective information (positive or negative) and inhibit emotion-driven behavioral responses (i.e. impulsivity), in order to remain focused on goal directed or adaptive behaviors. To assess this process, we used a modified version of the Multi-Source Interference Task (MSIT; a well-established paradigm eliciting cognitive interference)43, 44 by superimposing task presentations onto affective images selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS).45

The MSIT was developed to assess cognitive interference, or the ability to overcome task-irrelevant stimuli that distracts from task-relevant stimuli, requiring cognitive control to resolve. Participants are required to override a prepotent motor response by utilizing cognitive information (selective attention, visuospatial processing, decision making), to screen out irrelevant information and inhibit automatic behavior. A recent meta-analysis of MSIT studies in healthy controls found consistently increased activation of the dACC, dmPFC and SMA during interference trials across studies46. These findings have been suggested to relate to conflict monitoring (dACC) and motor planning (dmPFC, SMA) in the context of the inhibition of prepotent motor responses in order to successfully overcome interference and select the correct task response. Additionally, increased activation of the right insula, right VLPFC and putamen during interference trials was found across studies, suggesting increased processing of the saliency of interference. Abnormalities in dACC and dmPFC activation during interference trials has been shown across multiple clinical populations including schizophrenia,47, 48 major depressive disorder,49 post-traumatic stress disorder,50 obsessive compulsive disorder,51 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ADHD,52 and chronic pain.53 A previous study using the MSIT (without affective stimuli) in BD patients found reduced dACC and mid-cingulate activation in BD patients relative to healthy controls.54 In addition, BD patients evidenced increased response time and greater errors of omission (missed response) during trials requiring inhibitory control, suggestive of slower cognitive control processing, and greater errors of commission (incorrect response) during control conditions, indicative of greater impulsive responding. Thus, clinical populations including BD patients consistently show abnormal recruitment of fronto-parietal executive control regions during the cognitively demanding interference trials of the MSIT relative to healthy controls, with concomitant behavioral effects evidenced in BD.

Relevant to the current study, there are a few existing studies that have investigated the combination of the MSIT with irrelevant emotional distractors. In a study of healthy females, Jasinska and colleagues55 found the additional presence of negatively-valenced distractors (irrelevant flankers depicting facial expressions of fear) during interference trials significantly reduced dACC, DLPFC and insula/VLPFC activation relative to neutral trials, and significantly increased activation in these same regions during the less cognitively demanding non-interference trials. Similar findings for positively valenced trials were found, although to a lesser effect than negative valenced trials, with no significant differences between negative and positive valenced trials. A study of schizophrenic patients using a similarly adapted MSIT paradigm superimposed on irrelevant affective images found reduced DLPFC activation relative to healthy controls during all interference trials (negative or neutral), with strongest effects during negatively valenced interference trials.47 These studies suggest the inclusion of irrelevant emotional stimuli has a deleterious effect on trial performance on the MSIT, which may be further accentuated in clinical populations.

In the present study, we used a similarly modified MSIT-IAPS task to examine the ability of BD patients to overcome cognitive interference and inhibit automatic behavioral responses while affective systems are activated and competing for limited resources. We hypothesized BD patients would demonstrate significantly reduced recruitment of frontoparietal control and striatal regions relative to controls during interference trials on the modified MSIT-IAPS task in the context of negative and positive valenced images. Additionally, we hypothesized BD patients would evidence weaker functional connectivity between anterior insula and regions of the executive control network, and stronger functional connectivity between anterior insula and salience network regions during performance on cognitive interference trials in the presence of affective distractors. Thus, we hypothesized BD patients would exhibit under-reliance upon neurocircuitry related to regulatory control and over-reliance upon salience circuitry while attempting to regulate cognition and inhibit behavior in the context of irrelevant affective information. Further, we hypothesized BD patients would evidence slower reaction times and decreased task accuracy in the context of emotional stimuli relative to neutral stimuli.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were 39 individuals with DSM-IV bipolar I disorder, (mean age 36.69 ± 12.91; 16 female; Table 1) recruited through the Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and 36 healthy control participants (mean age 36.69 ± 12.91; 18 female). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation, in accordance with the guidelines of the Internal Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Eligible participants were English speakers, 18–65 years old. Patient participants were required to meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, current mild to moderate depressive symptoms, and be stable pharmacotherapy (no dose change within the past 8 weeks). Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of rapid cycling bipolar disorder subtype or current mixed episode, current or past psychosis or schizophrenia spectrum disorder, or lifetime substance/alcohol use disorder. Additional exclusion criteria for all participants (patients and controls) included presence of serious medical conditions, history of neurological disorder, history of moderate to severe head trauma, as well as standard fMRI contraindications (e.g. pregnancy, claustrophobia, non-removable metallic objects).

Table 1.

Study demographics.

| BD (n= 39) | HC (n = 36) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n (%) | n (%) | Sig. |

| Gender | 0.44 | ||

| Male | 23 (59.0) | 18(50.0) | |

| Female | 16(41.0) | 18(50.0) | |

| Age | 36.69 ± 12.92 | 34.69 ± 12.64 | 0.33 |

| Race | 0.49 | ||

| White | 35 (89.7) | 30(83.3) | |

| Black | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.3) | |

| East Asian | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Other or unreported | 2(5.1) | - | |

| Ethnicity | 0.60 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 38 (97.4) | 34 (94.4) | |

| Highest Level of Education | 0.67 | ||

| Doctorate | 3 (8.3) | - | |

| Masters | 2 (5.6) | 6(15.8) | |

| Bachelors | 20 (55.6) | 23 (15.8) | |

| Associate | 5(13.9) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Some College | 1 (2.8) | 8(21.1) | |

| High School/GED | 5(13.9) | - | |

| Clinical Measures | |||

| HAM-D-17 | 13.49(7.37) | 1.08(1.65) | <0.001 |

| YMRS | 5.15(4.98) | 0.56(1.16) | <0.001 |

| BDI | 19.28(11.53) | 2.52 (4.79) | <0.001 |

Note. Non-parametric tests for significance tested using Mann-Whitney U test.

Clinical measures

The presence of current mood symptoms was assessed using well-validated clinician-administered and self-report measures. Current presence of depressive symptoms was measured using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17-item version (HAM-D-17)56 and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II).57 Current manic or hypomanic symptoms were measured using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).58

fMRI Paradigm

MSIT-IAPS task.

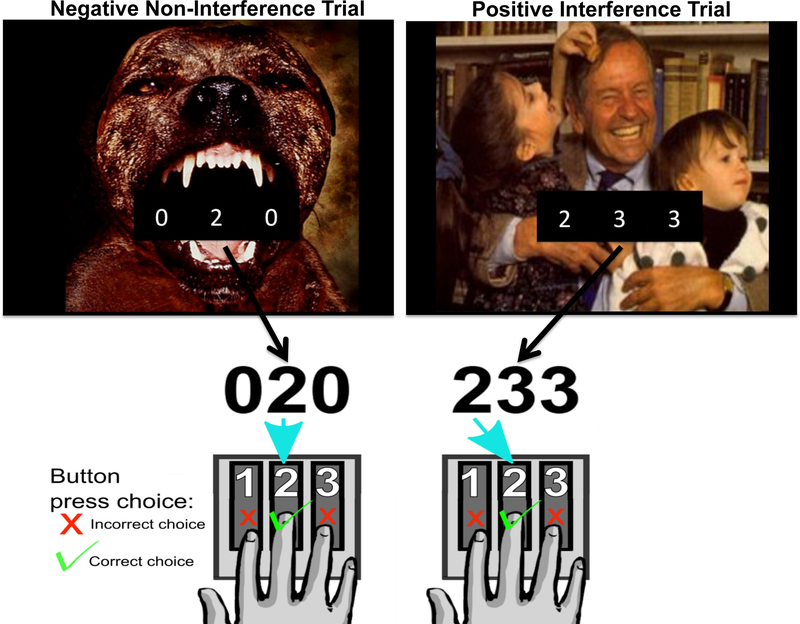

All participants completed an affective version of the MSIT (MSIT + IAPS, Figure 1) while undergoing fMRI. The MSIT paradigm was set up in a rapid-event related design. The MSIT incorporates aspects of well-established measures of cognitive interference (Stroop; Simon, and Eriksen Flanker tasks), and uses two different types of cognitive interference (spatial and flanker) to measure cognitive control.43, 44 Each trial of the MSIT was overlaid on an image from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS).45 IAPS pictures were either neutral, positive, or negative valenced, counterbalanced between the control and interference conditions. During each trial of the MSIT, a three-digit number (comprised using the numbers 0, 1, 2, or 3) was presented for 1.7 seconds on the screen. Each set contains two identical distractor numbers and a target number that differed from the distractors. Participants report via a button press the identity of the target number that differs from the two distractor numbers (Figure 1). During Noninterference (control) trials, distractor numbers are always zeros, and the identity of the target number always corresponds to its position on the button response pad (100, 020, 003). By contrast, during Interference trials, distractor numbers are always numbers other than 0, and the identity of the target number is always incongruent with its position on the button response pad (e.g. 211, 232, 331, etc.). Trial stimuli were presented on the screen for 1.7s, followed by an inter-trial interval (ITI) fixation cross of varying lengths (Figure 1). The trial and ITI sequence was determined using Optseq2 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/optseq).59 Trials were analyzed to examine the main effect of interference (All Interference – All Noninterference), the main effect of valence (All Negative – All Neutral; All Positive – All Neutral), and the interaction of interference and valence (Negative Interference – Negative Non-Interference; Positive Interference – Positive Non-Interference; Negative Interference – Neutral Interference; Positive Interference – Neutral Interference; Negative Non-Interference – Neutral Non-Interference; Positive Non-Interference – Neutral Non-Interference). Task behavioral performance was analyzed by calculating the average response time (reaction time, in milliseconds) and percentage of correct responses (accuracy) for each trial of interest.

Figure 1.

Illustration of MSIT-IAPS task trials, which consist of the Multisource Interference Task (MSIT) overlaid on images from the International Affective Picture Scale (IAPS). A) Example of a negatively valenced “Non-Interference” trial. The target number “2” is in the same position as the second finger on the number pad. B) Example of a positively valenced “Interference” trial. The target number “2” is in a different position than the second finger on the number pad. In the “Interference” trial, the prepotent response to press the first finger (matching the position of the target number) is inhibited in order to make the correct selection with the second finger. Trials not shown are “Positive Non-Interference,” “Neutral Non-Interference,” “Negative Interference,” “Neutral Interference.”

MRI scanning

MRI data were acquired using a 3.0-T whole-body scanner (Trio-System), equipped for echo planar imaging (Siemens Medical Systems, Iselin NJ) with a 3-axis gradient head coil. Head movements were restricted using foam cushions. Images were projected using a rear projection system and E-Prime stimulus presentation software was used to show the task stimuli (Psychology Software Tools; http://www.psychology-software-tools.mybigcommerce.com). Following automated scout and shimming procedures, two high-resolution 3D MPRAGE sequences (TR=2530ms, TE=3.39ms, flip angle=7o, voxel size = 1.3×1.0×1.3 mm) were collected for positioning of subsequent scans. FMRI images (i.e. blood oxygenation level dependent signal or BOLD) were acquired using T2* -weighted sequence (27 axial slices aligned perpendicular to the plane intersecting the anterior and posterior commissures, 5 mm thickness, skip 1 mm, TE=30ms, TR=1600ms, flip angle = 90o).

MRI Data Analysis

Functional Data were processed using SPM8 software (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm ). Each individual’s FMRI images were slice time corrected using slice number 7 as a reference, motion corrected using 2nd degree B-spline interpolation, co-registered to the T1 MPRAGE sequence and segmented into white, grey and CSF, spatially normalized to the standardized space established by the Montreal Neurologic Institute (MNI; www.bic.mni.mcgill.ca), resampled to 2mm3 voxels (anatomical images were resampled to 1mm3 voxels), and smoothed with a three-dimensional Gaussian kernel of 6 mm width (FWHM). All collected data had minimal head motion (< 3 mm linear movement in the orthogonal planes; <0.5 degrees radians of angular movement). The general linear model was applied to the time series60, convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function and a 128s high-pass filter. Serial autocorrelations were addressed with an AR(1) model. Movement parameters, derived from motion correction during preprocessing, were included in the model as regressors of no interest. For each subject, condition effects were modeled with the SPM canonical hemodynamic response function. For each subject (individual subjects’ analysis), condition effects were estimated at each voxel, and contrast images were produced for pre-specified contrasts of interest (see above). Individual subject contrast images were entered into a 2nd Level random effects flexible factorial for group-level comparisons of contrast effects in a priori specified regions of interest (ROIs), selected based upon prior reported findings of cognitive control and emotion regulation (see Introduction). To control for residual depressive and manic symptoms, scores on the HAM-D-17 and YMRS were entered as covariates. Specific ROIs included IPL, DLPFC, VLPFC, dorsal and ventral medial PFC (dmPFC, vmPFC), cingulate cortex, anterior insula, caudate, hippocampus, and amygdala. ROI masks were created using Anatomical Automatic Labeling tool61 implemented in the WFU Pickatlas (http://www.ansir.wfubmc.edu, see Supplement, Table S1).62, 63 Contrast results were examined at a small volume corrected (SVC) threshold of p<.005. Significant SVC results with a family-wise error (FWE) corrected p-value less than .05 were followed up for further analysis. The linear time series from significant contrasts that survived this additional FWE correction were extracted for further analysis using MarsBar.64

To assess functional connectivity differences as a function of task contrast, generalized PPI analyses65 were conducted in SPM8. At the individual subject level, condition contrasts of interest were modeled for main effects of cognitive interference and valence (Interference – Non-Interference trials; Negative – Neutral trials; Positive – Neutral trials), as well as the interaction of cognition and valence (Negative Interference – Negative Non-Interference; Positive Interference – Positive Non-Interference; Negative Interference – Neutral Interference; Positive Interference – Neutral Interference). A volume of interest (VOI) in the right anterior insula was selected as the seed region. Center-of-sphere for the anterior insula seed VOI was defined based upon results of the group-level GLM (right anterior insula, x y z = 44 20 2; see Table 2). The first eigenvariate was extracted by creating a spherical VOI with a radius of 6mm for each condition contrast of interest. Resulting individual contrast images were then entered into a 2nd Level GLM for group analysis in SPM. Functional connectivity between the anterior insula seed region and our a priori ROIs specified above was examined (IPL, DLPFC, VLPFC, dmPFC, vmPFC, cingulate cortex, caudate, hippocampus, and amygdala). Results of all group analyses were examined with a voxelwise threshold of p<.005. The linear time series from significant contrasts with a FWE corrected p-value less than .05 were extracted for further analysis using MarsBar.64

Table 2.

Behavioral results.

| Trial | BD | HCs | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMM (SE) | EMM (SE) |

Mean Diff. |

Sig.a | Lower | Upper | |

| Reaction time (ms) | ||||||

| All Interference | 868 (20) | 820 (21) | 48.0 | 0.17 | −20.8 | 116.7 |

| All Non-interference | 659 (20) | 609(21) | 49.0 | 0.16 | −20.3 | 118.4 |

| All Neutral | 762 (20) | 712(21) | 50.4 | 0.15 | −18.0 | 118.9 |

| All Positive | 762 (20) | 713 (20) | 48.9 | 0.15 | −17.6 | 115.5 |

| All Negative | 765 (20) | 719(21) | 46.1 | 0.18 | −21.4 | 113.6 |

| Neutral Interference | 870(21) | 819(22) | 51.1 | 0.16 | −20.3 | 122.5 |

| Positive Interference | 868 (20) | 824 (21) | 43.8 | 0.20 | −23.8 | 111.5 |

| Negative Interference | 865 (20) | 816(21) | 49.0 | 0.16 | −19.4 | 117.3 |

| Neutral Non-interference | 655 (20) | 605(21) | 49.8 | 0.16 | −19.6 | 119.2 |

| Positive Non-interference | 657 (20) | 603(21) | 54.1 | 0.13 | −15.3 | 123.5 |

| Negative Non-interference | 664(21) | 621 (21) | 43.2 | 0.22 | −26.8 | 113.3 |

| Accuracy (%) | ||||||

| All Interference | 82.3 (2.5) | 91.3(2.6) | −8.9 | 0.04 | −17.5 | −0.4 |

| All Non-interference | 96.5(1.0) | 99.5(1.0) | −6.0 | 0.07 | −6.3 | 0.2 |

| All Neutral | 90.0(1.5) | 95.6(1.6) | −5.6 | 0.04 | −10.8 | −0.4 |

| All Positive | 89.8(1.6) | 95.7(1.7) | −5.9 | 0.04 | −11.5 | −0.4 |

| All Negative | 88.3 (1.8) | 94.8(1.9) | −6.5 | 0.04 | −12.5 | −0.4 |

| Neutral Interference | 83.5 (2.4) | 91.7(2.5) | −8.2 | 0.05 | −16.3 | 0.0 |

| Positive Interference | 83.1 (2.6) | 91.6(2.7) | −8.4 | 0.06 | −17.2 | 0.4 |

| Negative Interference | 80.3 (2.8) | 90.5 (2.9) | −10.2 | 0.03 | −19.6 | −0.9 |

| Neutral Non-interference | 96.5 (1.0) | 99.5(1.0) | −3.0 | 0.07 | −6.2 | 0.2 |

| Positive Non-interference | 96.5 (1.0) | 99.9(1.0) | −3.4 | 0.05 | −6.7 | −0.1 |

| Negative Non-interference | 96.4(1.1) | 99.1(1.1) | −2.7 | 0.15 | −6.4 | 1.0 |

Note: Results of MANCOVA, controlling for residual depression and mania symptoms. EMM (SE) = estimated marginal means and standard errors, derived from omnibus MANCOVA model.

Bonferroni corrected.

Behavior Analysis

Behavioral performance on the MSIT-IAPS task was assessed by calculating the mean reaction time to response score (reaction time) and percentage of accurate responses made (accuracy). To assess differences in task performance between groups, we conducted a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) controlling for baseline symptom severity (HAM-D-17, BDI-II, YMRS) and medication load (see below). Follow up pairwise t-tests were conducted and Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for multiple comparisons.

To assess the relationship between task-related regional activation and functional connectivity and behavioral performance, a series of bivariate, 2-tailed Pearson’s correlations were conducted in SPSS (version 20.0; IBM) between behavioral response time and accuracy scores and extracted linear time series from GLM and gPPI modeled contrasts. To correct for multiple comparisons, 95% confidence intervals for the results of correlational analyses were calculated using an iterative bootstrap method (resample and replace, 1000 samples) in SPSS.

Medication effects

The effects of psychotropic medications (medication load) on task performance and MRI results were assessed using an established approach by Phillips and colleagues.66–68 For each participant, the dose of each class of medication (antidepressants, mood-stabilizers, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics) is coded as absent (0), low (1), or high (2) using the dosing guidelines, and a participant’s total medication load is reflected as a sum of these scores (range = 0–8). To assess the effects of medication, individual medication load scores were regressed on measures of task behavior (reaction time, accuracy) and significant findings from the ROI contrast analyses and gPPI results.

Results

Demographics

Complete participant demographics are presented in Table 1. No significant differences were found between healthy control and BD patient groups in age, sex, ethnicity, race, or years of education. BD participants on average scored in the mild to moderate range on measures of depressive symptoms (HAM-D-17; BDI), and in the range of remission on a measure of manic symptoms (YMRS). Healthy controls were asymptomatic across all measures. Medication load for BD patients ranged from 0–8, with a mean of 2.94 (±2.20), suggesting low to moderate medication load on average.

Behavioral Results

Table 2 shows complete behavioral results across all trial types. Data from one BD participant failed to record during scanning, therefore results presented are for the remaining 74 participants. Results from the omnibus MANCOVA controlling for residual depression and mania symptoms showed a significant difference between groups for accuracy (F(2, 37) = 2.39; p = .03, η2 = .22) but not reaction time (F(2, 37) = 2.06; p = .16, η2 = .03). Averaging across all trial types, BD participants committed significantly more response errors relative to healthy controls, even after controlling for residual symptoms (Meandiff (SE) = −5.99 (2.75), p = .03 Bonferroni corrected). Looking at specific trial types, BD participants committed significantly more errors across all three valence presentations regardless of interference [all neutral: Meandiff (SE) = −5.58 (2.62), p = .04 Bonferroni corrected; all negative: Meandiff (SE) = −6.48(3.04), p = .04 Bonferroni corrected; all positive: Meandiff (SE) = −5.91(2.79), p = .04 Bonferroni corrected]. The strongest effect was seen during negative valenced Interference trials (Meandiff (SE) = −10.24 (4.71), p = .03 Bonferroni corrected).

fMRI Results

Effect of Cognitive Interference (Interference vs. Non-Interference trials).

Results of Interference vs. Non-Interference trials are summarized in Table 3. Across all Interference – Non-Interference trials regardless of valence (main effect Interference vs. Non-Interference), bipolar patients showed significantly less activation of right dmPFC, right IPL, right anterior insula, bilateral mid cingulate and right VLPFC, and significantly greater activation of right DLPFC and right posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) relative to HC participants (Table 3, Figure 2). Bipolar patients also evidenced significantly less activation of left IPL [t(365) = 3.23, p=.001 (p = .30 FWE)], left insula [t(365) = 3.47, p<.001 (p = .18 FWE)], and left VLPFC [t(365) = 3.55, p<.001 (p = .30 FWE)], but these did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons. No effects surviving uncorrected or corrected significance thresholds were found when examining only Negative Interference – Negative Non-Interference trials or only Positive Interference – Positive Non-Interference trials.

Table 3.

fMRI contrast results.

| MNI Coordinatesa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BA | x | y | z | Vol (mm3) | t−score | p (FWE) |

| Interference > Non-interference | |||||||

| HCs > BD | |||||||

| R. dmPFC | 6 | 2 | 4 | 62 | 1224 | 5.57 | <.001*** |

| R. IPL | 40 | 46 | −44 | 38 | 248 | 5.17 | <.001*** |

| R. Anterior Insula | 13/47 | 44 | 20 | 2 | 1000 | 3.53 | 0.05** |

| L. Mid Cingulate | 8/32 | −14 | 14 | 46 | 888 | 4.7 | 0.01** |

| R. Mid Cingulate | 8/32 | 12 | 16 | 44 | 1216 | 3.78 | 0.07** |

| R. VLPFC | 44 | 48 | 4 | 20 | 1128 | 3.78 | 0.07** |

| BD>HCs | |||||||

| R. DLPFC | 9 | 44 | 22 | 30 | 848 | 4.10 | 0.05* |

| R.PCC | 23 | 4 | −28 | −38 | 912 | 3.76 | 0.05* |

Note. Table shows family-wise error (FWE) corrected p-values, controlling for residual depression and mania symptoms. BD = bipolar patients. HC = healthy controls. DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. dmPFC = dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. IPL = inferior parietal lobule. PCC = posterior cingulate cortex. VLPFC = ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

uncorrected p <.01.

uncorrected p <.001.

uncorrected p<.0001.

Figure 2.

Regions of significantly greater activation in healthy controls relative to bipolar patients during Interference > Non-Interference contrast conditions. Regions include (a) right dmPFC (x=2 y=2 z=60); (b) right inferior parietal lobule (x=46 y=−44 z=38); and (c) right anterior insula (x=44 y=20 z=2). Images displayed at p <.005 uncorrected, whole brain.

Effect of Valence (Negative, Positive vs. Neutral trials).

Across all Negative – Neutral trials regardless of interference, BD participants showed significantly greater DLPFC and VLPFC activation, but these results did not survive FWE correction for multiple comparisons [left DLPFC: t(365) = 3.59, p <.001 (p = .41 FWE); right DLPFC: t(365) = 3.56, p <.001 (p = .44 FWE); left VLPFC: t(365) = 3.22, p = .001 (p = .60 FWE); right VLPFC: t(365) = 3.07, p = .001 (p = .75 FWE)]. No effects surviving uncorrected or corrected significance thresholds were found for Positive – Neutral trials.

Functional connectivity (gPPI).

Results of gPPI analysis are summarized in Table 4. Because we did not find any significant effects of positive valence trials, gPPI analyses included only negative and neutral valence trials. Significant differences in functional connectivity were found in BD patients relative to controls during Negative Interference – Negative Non-Interference trials between the right anterior insula seed region and bilateral dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC; Figure 3a), left dmPFC, bilateral DLPFC, bilateral vmPFC, bilateral IPL, bilateral caudate, and bilateral hippocampus (Table 4). Across all anterior insula seed- ROI target pairs, BD patients evidenced positively correlated activation, whereas healthy controls evidenced negatively correlated activation (See supplement, Figure S1).

Table 4.

fMRI gPPI results.

| MNI Coordinatesa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | BA | x | y | z | Vol (mm3) | t−score | p (FWE)b |

| Interference > Non-interference | |||||||

| HCs > BD | |||||||

| No significant results at FWE <.10 | |||||||

| BD > HCs | |||||||

| R. Hippocampus | 34 | −26 | −14 | 56 | 3.73 | 0.05*** | |

| Negative > Neutral | |||||||

| HCs > BD | |||||||

| No significant results at FWE <.10 | |||||||

| BD > HCs | |||||||

| L. IPL | −30 | −50 | 46 | 147 | 4.06 | 0.03*** | |

| R. dACC | 14 | 28 | 28 | 48 | 4.75 | 0.002*** | |

| Negative Interference > Negative Non-Interference | |||||||

| HCs > BD | |||||||

| No significant results at FWE <.10 | |||||||

| BD>HCs | |||||||

| R. Hippocampus | 34 | −22 | −14 | 217 | 5.06 | <0.000 | |

| L. Hippocampus | −34 | −38 | −4 | 56 | 4.27 | 0.008 | |

| R. dACC | 32 | 12 | 28 | 20 | 548 | 5.03 | <0.000 |

| L. dACC | 10 | −12 | 52 | 2 | 83 | 4.71 | 0.002 |

| L. dmPFC | −14 | 44 | 26 | 814 | 5.28 | 0.001 | |

| R. Caudate | 14 | 14 | 14 | 274 | 4.69 | 0.001 | |

| L. Caudate | −16 | 22 | 10 | 132 | 4.48 | 0.003 | |

| L. DLPFC | −32 | 2 | 50 | 158 | 5.05 | 0.003 | |

| R. DLPFC | 32 | 26 | 34 | 1416 | 4.85 | 0.006 | |

| R. IPL | 56 | −44 | 46 | 271 | 4.46 | 0.007 | |

| L. IPL | −40 | −36 | 38 | 173 | 4.16 | 0.02 | |

| R. vmPFC | 16 | 52 | −2 | 100 | 4.37 | 0.004 | |

| L. vmPFC | −12 | 52 | −2 | 34 | 3.96 | 0.02 | |

| Negative Interference > Neutral Interference | |||||||

| HCs > BD | |||||||

| No significant results at FWE <.10 | |||||||

| BD>HCs | |||||||

| R. dmPFC | 26 | 6 | 44 | 147 | 5.13 | 0.002 | |

| L. dmPFC | −12 | 14 | 48 | 333 | 4.93 | 0.005 | |

| R. Hippocampus | 26 | −18 | −14 | 107 | 4.54 | 0.003 | |

| L. SPL | −30 | −50 | 44 | 329 | 5.73 | <0.000 | |

| L. IPL | 40 | −44 | −34 | 36 | 124 | 4.05 | 0.03 |

| R. dACC | 14 | 28 | 28 | 48 | 4.75 | 0.002 | |

Note. Table shows family-wise error (FWE) corrected p-values. BD = bipolar patients. HC = healthy controls. dACC = dorsal anterior cingulate. DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. dmPFC = dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. IPL = inferior parietal lobule. vmPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Figure 3.

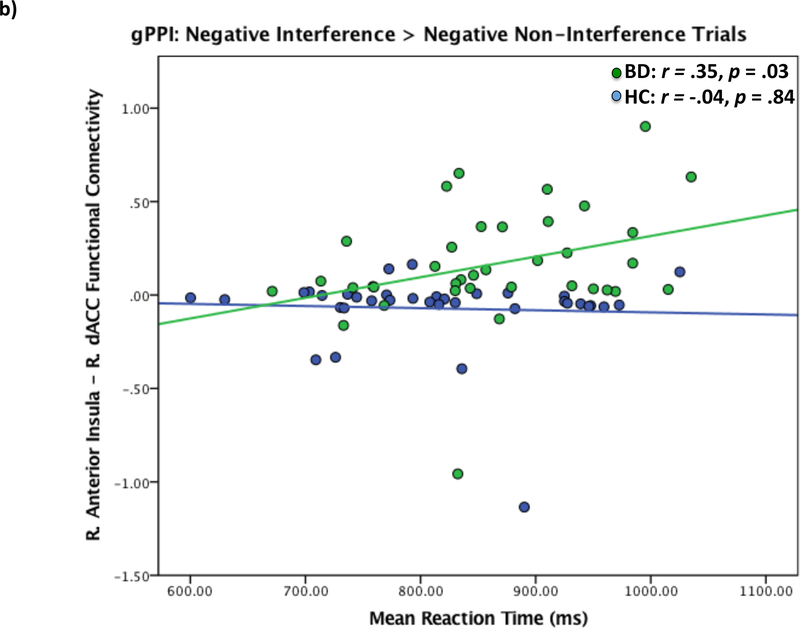

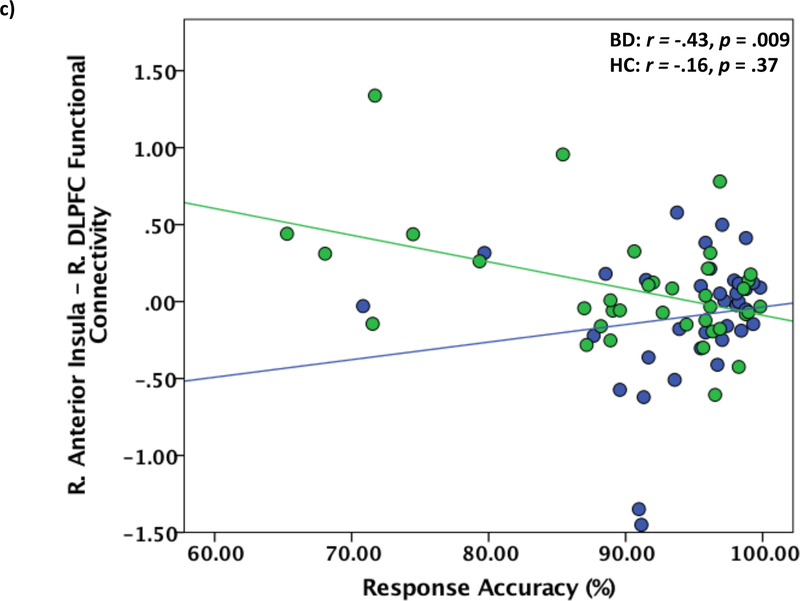

Functional connectivity of right anterior insula and right dACC in bipolar patients relative to healthy controls during Negative Interference > Negative Non-Interference trials. a) Right anterior insula – right dACC functional connectivity maps showing dACC max voxel (x=12 y=28 z = 20). Results displayed at p < .005 uncorrected. b) Correlations between reaction time during negative interference trials and right anterior insula – right dACC functional connectivity. dACC = dorsal anterior cingulate. c) Correlations between reaction time during negative interference trials and right anterior insula – right DLPFC functional connectivity. DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Effects of Medications

Medication load in BD patients significantly negatively predicted bilateral anterior insula activation (left: β = −.49, p = .002; right: β = −.37, p = .03). No other significant correlations between medication load and regional activation, functional connectivity, or task performance were found.

Relationship to Behavior

Activation in the left IPL during Interference trials was significantly negatively correlated with reaction time for BD patients only (r = −.33, p =.04, Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.70, −0.08), such that greater activation of the left IPL corresponded to faster reaction time. No other significant relationships between task performance and ROI activations were found. For comparisons with gPPI results, functional connectivity between the right anterior insula and right dACC during Negative Interference > Negative Non-Interference trials was significantly positively related to reaction time for BD patients only, such that stronger positive functional connectivity was related to slower reaction times (r =.35 p =.03, Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.12, 0.65; Figure 3b). Functional connectivity between right anterior insula and right DLPFC during Negative Interference > Negative Non-Interference trials was significantly negatively associated with response accuracy in BD patients only, such that stronger positive functional connectivity was related to less response accuracy (r = −.43, p =.009, Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.66, −0.09; Figure 3c). For healthy controls only, right anterior insula and right hippocampus functional connectivity during Negative Interference > Negative Non-Interference trials was significantly negatively correlated with reaction time (r = −.52, p = .002, Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.77, −0.20) and significantly positively correlated with response accuracy (r = .45, p = .008, Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.15, 0.73), such that stronger negative insula-hippocampus functional connectivity was related to slower reaction times and greater accuracy (see Supplement, Figure S2). The same pattern was found for right anterior insula – right vmPFC functional connectivity for healthy controls only (reaction time: r = −.43 p =.01, Bootstrap 95% CI: −0.65, −0.18; accuracy: r = .43, p =.01, Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.19, 0.64; Supplement, Figure S3).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to examine the integration of cognition, emotion, and behavioral inhibition in patients with BD using a complex cognitive task superimposed on irrelevant affective stimuli. Consistent with our first hypothesis, BD patients showed decreased regional activations relative to healthy controls across a distributed set of fronto-parietal executive control regions during cognitive interference, including right IPL, right dmPFC/bilateral mid-cingulate, and right VLPFC. These effects were found across all interference trials regardless of the valence of affective stimuli, and are consistent with a previous study using the original (non-affective) MSIT in BD. However, in addition to reduced recruitment of cognitive control, decreased activation of the right anterior insula (salience network) and increased activation of both the posterior cingulate cortex (default mode network), and right DLPFC (executive control network), was also found in BD patients relative to healthy controls across interference trials. This suggests the addition of irrelevant affective information further impairs BD performance on a complex cognitive task, potentially through increased self-monitoring (posterior cingulate), increased compensatory control (DLPFC) and decreased recruitment of a key region implicated in flexibly switching between affective and cognitive processing modes (anterior insula).

Consistent with our second hypothesis, BD patients showed stronger functional connectivity between anterior insula and the dACC, a region of the salience network, with BD patients evidencing positive functional connectivity and healthy controls evidencing negative functional connectivity. Further, this connectivity was significantly positively related to reaction time in BD patients, such that stronger positive functional connectivity was associated with slower (less efficient) reaction times. However, contrary to hypotheses, stronger positive functional connectivity was also found between anterior insula and several fronto-parietal executive control network regions (bilateral IPL, DLPFC, dmPFC) relative to healthy controls, and also in the same direction (positive connectivity in BD patients, negative connectivity in healthy controls; see Supplement, Figure S1). Further, these functional connectivity effects were found only during negatively valenced trials, and most strongly during negative interference trials. Collectively, these results are interesting, in that, prima facie, they seem counterintuitive. One might conclude positive functional connectivity between regions to imply increased efficiency, or to be related to increased causal (i.e. inhibitory) connectivity. However, an alternate interpretation of increased positive functional connectivity strength argues for decreased efficiency, insomuch as prolonged concurrent activation of two regions might imply failure of one region to exert effects on the corresponding region. Indeed, increased positive anterior insula-DLPFC functional connectivity, a key node of the frontoparietal control network, was significantly associated with decreased rather than increased response accuracy. Hence, increased positive functional connectivity strength, which is a measure of correlated activity over time, might imply less efficient regulation of otherwise correlated regions, with detrimental behavioral consequences. A more precise understanding of the clinical implications of positive versus negative functional connectivity patterns is a research area in particular need of further attention and would help clarify the results presented here. Overall, results from the current study suggest the ability to adaptively utilize frontoparietal control systems rather than salience or default mode systems in order to disengage from irrelevant emotional stimuli and meet task demands is compromised in BD patients.

Our third hypothesis, that BD patients would evidence slower reaction times and decreased task accuracy in the context of emotional stimuli relative to neutral stimuli, was only partially supported. After correction for multiple comparisons, we found no significant differences in reaction times across all task conditions between BD patients and healthy controls. This is in contrast to the findings of Gruber et al.,54 using the original MSIT task, in which BD patients exhibited significantly slower reaction times across interference trials relative to healthy controls. The difference in findings may be accounted for by the presence of irrelevant emotional stimuli in the modified task, which may affect performance in healthy control subjects and reduce differences in reaction time between healthy controls and BD patients below a statistically significant threshold. However, in the current study, behavioral effects were calculated controlling for residual symptoms of depression and mania, and more stringent corrections for multiple comparisons were applied, which may also account for the differences between studies. Indeed, in the absence of these controls, BD patients evidenced significantly slower reaction times relative to healthy controls across all task conditions (all p’s <.05). Therefore, it is unclear whether the presence of emotional distractors, the presence of residual mood symptoms, or the interaction of both ultimately impacts performance speed in BD patients.

We did find significant differences in response accuracy across all negative and neutral interference trials, which is in keeping with previous findings of reduced accuracy during interference.54 Interestingly, we did not find a significant difference in accuracy during positively valenced interference trials, but we did find a significant difference in accuracy during positively valenced non-interference trials. This may be due to the salience of interference trials themselves – the more difficult and challenging interference trials may evoke distracting negative affect regardless of the presence of irrelevant affective stimuli, and this negative affect may override the distracting effect of positively valenced stimuli. In the absence of this additional cognitive challenge (i.e. non-interference trials), the presence of positive stimuli may have a stronger distracting effect. Overall, future replication studies are needed to disambiguate these collective behavioral effects.

Unlike previous studies using emotional Stroop-like tasks to measure interference,40 we did not find significantly greater regional limbic (amygdala, hippocampus) activation in BD patients relative to controls across any comparisons. However, the current study did find significant differences in functional connectivity patterns between anterior insula and limbic regions (hippocampus, caudate) in BD patients relative to healthy controls during negatively valenced interference trials. As was the case with anterior insula connectivity to salience network and fronto-parietal executive control network regions, BD patients again evidenced positively correlated functional connectivity between anterior insula and these regions, whereas healthy controls evidenced negatively correlated functional connectivity (see Supplement, Figure S1). In addition, consistent with results found by Favre and colleagues39 reported above, BD patients evidenced positively correlated functional connectivity between anterior insula and the ventromedial PFC, a key region of the default mode network, whereas healthy controls exhibited negative functional connectivity. These results suggest regional limbic reactivity to irrelevant emotional stimuli may not differentiate BD patients from controls per se, but rather increased synchronous engagement of salience and default mode network regions may compromise disengagement from irrelevant affective stimuli.

A few additional outcomes of the current study merit mention. First, results from the current study contribute to a growing literature implicating the IPL in BD.69–71 Deviations in IPL activation between BD patients and healthy controls during cognitive interference emerged as one of the strongest regional activation effects, alongside dmPFC activation. Further, decreased functional connectivity between anterior insula and the IPL was significantly associated with deficits in behavioral task performance. These findings are intriguing in light of recent research implicating dysfunctional IPL recruitment as a potential genetic risk factor for BD.71 Specifically, in a study of BD patients and their first degree relatives utilizing the Stroop task, Pompeii and colleagues found abnormalities in IPL activation distinguished BD and their unaffected relatives from controls.70 Data from our own lab show abnormal resting-state functional connectivity between right anterior insula and the IPL in BD patients distinguishes them from unipolar depressed and healthy controls after controlling for medication effects.69 As a key node in the fronto-parietal executive control network, the IPL has been shown to play a major role in emotion-cognition integration and is an important regional hub within an integrative multi-network system implicated in orienting attention and regulating cognitive resources in response to salient stimuli.72–74 The IPL also shares strong functional connections to anterior insula, VLPFC, and dmPFC and is strongly activated in tasks requiring simultaneous processing of interoceptive or affective cues and cognitive demands.37, 75 Thus, the decreased recruitment of IPL and corresponding deficits in task performance found in the current study further implicates this region in the dysfunctional cognitive-affective integration and regulation seen in BD.

Second, whereas behavioral and neural responses to negative valenced stimuli differentiated BD patients from healthy controls, we did not find effects for positive valenced stimuli. This may be due to the nature of the positive stimuli used in the present study. Specifically, dysfunction related to positive valenced stimuli in BD primarily relates to over approach to appetitive stimuli in the context of increased arousal. The positively valenced stimuli in the present study (positive images) may have failed to elicit a similar autonomic response in BD patients; therefore, meaningful neural differences in the context of positive stimuli may not have been detected.

There are limitations to the interpretation of the study results presented here. First, BD patients include a heterogeneous mix of BD symptom presentations, ranging from mildly to moderately depressed. In addition, the current study included only BD-I patients. Therefore, it is unclear whether differential results would be found when examining BD-I versus BD-II patients or in the absence of residual depressive symptoms. Second, the current study relied on a more conservative ROI approach. Examining task effects in whole-brain functional networks would help to clarify results presented here. Third, as mentioned above, affective images have somewhat limited ecological validity in eliciting emotional responses, and the stimuli here was more effective at eliciting reactions to negative rather than positive stimuli. Future studies using more ideographic or personally relevant stimuli may improve the ecological validity of the affective component of the task.76

Conclusions

Understanding the neural correlates of cognition-emotion integration in BD is important not only for the purposes of shedding light on the pathophysiology of BD but also to aid in the identification of potential treatment targets. The current study contributes to existing studies of cognition-emotion integration in BD by examining behavioral and neural responses to a task requiring attention to ongoing task goals and the inhibition of prepotent behavioral responses in the context of irrelevant emotional stimuli. Results of our analyses found BD patients less able to recruit regions implicated in cognitive control in order to accomplish task goals, and concurrent deficits in task performance. Further, deviations in functional connectivity between the anterior insula and regions of all three major functional networks (salience, default mode, executive control) suggest overall inefficiency in recruiting frontoparietal executive control networks to disengage from irrelevant salient stimuli. Results from the present study add to existing literature suggesting a particular role of the IPL in cognitive-affective integration and cognitive control in BD. Future studies are needed to understand the relationship between patterns of functional connectivity identified in the current study and broader intra- and inter-network connectivity in order to identify potential targets for rehabilitative intervention, such as non-invasive neuromodulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ellard gratefully acknowledges support from the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Training Program in Recovery and Restoration of CNS Health and Function (T32 NS100663–01). Dr. Deckersbach gratefully acknowledges support from a NIMH-funded Mentored Patient Oriented Research Grant (K23 MH074895–01). Drs. Dougherty, Widge and Deckersbach acknowledge additional support from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-14-2-0045 issued by ARO contracting office in support of DARPA’s SUBNETS Program. The views, opinions, and/or findings expressed are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. Dr. Dougherty further acknowledges support from NIH grants (R01 MH045573–24) and (1R01AT008563–01A1) and Medtronic.

Footnotes

Disclosures

No commercial funding to any contributing authors directly supported the preparation of this work. Additional funding disclosures: Dr. Nierenberg reports grants and personal fees from Takeda/Lundbeck and AlfaSigma (formerly known as PamLabs). He has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKlein, NeuroRx Pharma, Marriott Foundation, National Institute of Health, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, Janssen, Intracellular Therapies, and Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Dr. Nierenberg also receives personal or consulting fees from Alkermes, PAREXEL, Sunovian, Naurex, Hoffman La Roche/Genentech, Eli Lilly & Company, Pfizer, SLACK Publishing, and Physician’s Postgraduate Press, Inc. Dr. Van Dijk is currently employed by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer Inc. had no input or influence on the study design, data collection, data analyses, or interpretation of results. Dr. Dougherty receives device donations and has received consulting income from Medtronic. Dr. Dougherty has pending patent applications related to deep brain stimulation for mental illness. Dr. Dougherty further reports consulting income from Insys, speaking fees from Johnson & Johnson, and research support from Cyberonics and Roche. Dr. Deckersbach reports research support from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Depression and Bipolar Alternative Treatment Foundation, International OCD Foundation, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, Tourette Syndrome Association, National Institute on Aging, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the Forest Research Institute, Shire Development, Inc., Medtronic, Cyberonics, Northstar, and Takeda. He has received personal/consulting fees from BrainCells, Inc., Clintara, Inc., Systems Research and Applications Corporation, Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, National Association of Social Workers Massachusetts, Massachusetts Medical Society, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Oxford University Press. He has received both grants and personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Tufts University, National Institute of Mental Health, and Cogito, Inc. No further biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest are reported by contributing authors.

References

- 1.Gruber J, Kogan A, Mennin D, Murray G. Real-world emotion? An experience-sampling approach to emotion experience and regulation in bipolar I disorder. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2013;122(4):971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruber J, Purcell AL, Perna MJ, Mikels JA. Letting go of the bad: Deficit in maintaining negative, but not positive, emotion in bipolar disorder. Emotion. 2013;13(1):168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Rheenen TE, Rossell SL. Phenomenological predictors of psychosocial function in bipolar disorder: Is there evidence that social cognitive and emotion regulation abnormalities contribute? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;48(1):26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanske P, Heissler J, Schönfelder S, Forneck J, Wessa M. Neural correlates of emotional distractibility in bipolar disorder patients, unaffected relatives, and individuals with hypomanic personality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1487–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson SL, Gruber J, Eisner LR. Emotion and Bipolar Disorder In: Rottenberg J, Johnson SL, eds. Emotion and Psychopathology: Bridging Affective and Clinical Science. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MJ, Cahill CM, Malhi GS. The cognitive and neurophysiological basis of emotion dysregulation in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2007;103(1):29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruber J, Harvey AG, Gross JJ. When trying is not enough: Emotion regulation and the effort–success gap in bipolar disorder. Emotion. 2012;12(5):997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heissler J, Kanske P, Schönfelder S, Wessa M. Inefficiency of emotion regulation as vulnerability marker for bipolar disorder: evidence from healthy individuals with hypomanic personality. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;152:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend J, Altshuler LL. Emotion processing and regulation in bipolar disorder: a review. Bipolar disorders. 2012;14(4):326–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Hughes JH, Watson S, Gray JM, Ferrier IN, Young AH. Neurocognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar affective disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186(1):32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varga M, Magnusson A, Flekkøy K, Rønneberg U, Opjordsmoen S. Insight, symptoms and neurocognition in bipolar I patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Cakir S, Barrett JA, Najt P, Serap Monkul E, Maples N, Velligan DI, Soares JC. Differential working memory impairment in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: effects of lifetime history of psychosis. Bipolar disorders. 2006;8(2):117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addington J, Addington D. Attentional vulnerability indicators in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia research. 1997;23(3):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bora E, Vahip S, Akdeniz F. Sustained attention deficits in manic and euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark L, Kempton MJ, Scarnà A, Grasby PM, Goodwin GM. Sustained attention-deficit confirmed in euthymic bipolar disorder but not in first-degree relatives of bipolar patients or euthymic unipolar depression. Biological psychiatry. 2005;57(2):183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muhtadie L, Johnson SL, Carver CS, Gotlib IH, Ketter TA. A profile approach to impulsivity in bipolar disorder: the key role of strong emotions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2014;129(2):100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Increased trait‐like impulsivity and course of illness in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders. 2009;11(3):280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy F, Sahakian B, Rubinsztein J, Michael A, Rogers R, Robbins T, Paykel E. Emotional bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychological medicine. 1999;29(6):1307–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaladjian A, Jeanningros R, Azorin J-M, Nazarian B, Roth M, Mazzola-Pomietto P. Reduced brain activation in euthymic bipolar patients during response inhibition: an event-related fMRI study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;173(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips ML, Vieta E. Identifying functional neuroimaging biomarkers of bipolar disorder: toward DSM-V. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2007;33(4):893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowland JE, Hamilton MK, Lino BJ, Ly P, Denny K, Hwang E-J, Mitchell PB, Carr VJ, Green MJ. Cognitive regulation of negative affect in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2013;208(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolkenstein L, Zwick JC, Hautzinger M, Joormann J. Cognitive emotion regulation in euthymic bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;160:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolur U, Reddy Y, John J, Kandavel T, Jain S. Sustained attention and executive functions in euthymic young people with bipolar disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189(5):453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath J, Chapple B, Wright M. Working memory in schizophrenia and mania: correlation with symptoms during the acute and subacute phases. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;103(3):181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deckersbach T, McMurrich S, Ogutha J, Savage C, Sachs G, Rauch S. Characteristics of non-verbal memory impairment in bipolar disorder: the role of encoding strategies. Psychological medicine. 2004;34(5):823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badcock JC, Michie PT, Rock D. Spatial working memoryand planning ability: Contrasts between schizophreniaand bipolar i disorder. Cortex. 2005;41(6):753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochsner KN, Hughes B, Robertson ER, Cooper JC, Gabrieli JD. Neural systems supporting the control of affective and cognitive conflicts. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21(9):1842–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochsner KN, Silvers JA, Buhle JT. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251:E1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niendam TA, Laird AR, Ray KL, Dean YM, Glahn DC, Carter CS. Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;12(2):241–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nee DE, Wager TD, Jonides J. Interference resolution: insights from a meta-analysis of neuroimaging tasks. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;7(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan J, Owen AM. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends in neurosciences. 2000;23(10):475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menon V Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2011;15(10):483–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas Yeo B, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Zöllei L, Polimeni JR. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of neurophysiology. 2011;106(3):1125–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Structure and Function. 2010;214(5–6):655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(34):12569–12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu X, Liu X, Van Dam NT, Hof PR, Fan J. Cognition-emotion integration in the anterior insular cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(1):20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goulden N, Khusnulina A, Davis NJ, Bracewell RM, Bokde AL, McNulty JP, Mullins PG. The salience network is responsible for switching between the default mode network and the central executive network: replication from DCM. Neuroimage. 2014;99:180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Favre P, Polosan M, Pichat C, Bougerol T, Baciu M. Cerebral correlates of abnormal emotion conflict processing in euthymic bipolar patients: a functional MRI study. PloS one. 2015;10(8):e0134961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagopoulos J, Malhi GS. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of emotional Stroop in euthymic bipolar disorder. Neuroreport. 2007;18(15):1583–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malhi GS, Lagopoulos J, Sachdev PS, Ivanovski B, Shnier R. An emotional Stroop functional MRI study of euthymic bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7 Suppl 5:58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etkin A, Egner T, Peraza DM, Kandel ER, Hirsch J. Resolving emotional conflict: a role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating activity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2006;51(6):871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bush G, Shin LM. The Multi-Source Interference Task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nature protocols. 2006;1(1):308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bush G, Shin L, Holmes J, Rosen B, Vogt B. The Multi-Source Interference Task: validation study with fMRI in individual subjects. Molecular psychiatry. 2003;8(1):60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention. 1997:39–58. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng Y, Wang X, Wang Y, Zhou C. Neural correlates of interference resolution in the multi-source interference task: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2018;14(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tully LM, Lincoln SH, Hooker CI. Lateral prefrontal cortex activity during cognitive control of emotion predicts response to social stress in schizophrenia. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;6:43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heckers S, Weiss AP, Deckersbach T, Goff DC, Morecraft RJ, Bush G. Anterior cingulate cortex activation during cognitive interference in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB, Harrison BJ. Task-related deactivation and functional connectivity of the subgenual cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2012;3:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin LM, Bush G, Milad MR, Lasko NB, Brohawn KH, Hughes KC, Macklin ML, Gold AL, Karpf RD, Orr SP. Exaggerated activation of dorsal anterior cingulate cortex during cognitive interference: a monozygotic twin study of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):979–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yücel M, Harrison BJ, Wood SJ, Fornito A, Wellard RM, Pujol J, Clarke K, Phillips ML, Kyrios M, Velakoulis D. Functional and biochemical alterations of the medial frontal cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64(8):946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bush G, Holmes J, Shin LM, Surman C, Makris N, Mick E, Seidman LJ, Biederman J. Atomoxetine increases fronto-parietal functional MRI activation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2013;211(1):88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao CP, Zhang QL, Bao FX, Liao X, Yang XL, Zhang M. Decreased activation of cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network during an attention-demanding task in patients with chronic low back pain. Neuroradiology. 2014;56(10):903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gruber SA, Dahlgren MK, Sagar KA, Gonenc A, Norris L, Cohen BM, Ongur D, Lewandowski KE. Decreased Cingulate Cortex activation during cognitive control processing in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;213:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jasinska AJ, Yasuda M, Rhodes RE, Wang C, Polk TA. Task difficulty modulates the impact of emotional stimuli on neural response in cognitive-control regions. Frontiers in psychology. 2012;3:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio. 1996;78(2):490–498. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young R, Biggs J, Ziegler V, Meyer D. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133(5):429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dale AM. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI. Human brain mapping. 1999;8(2–3):109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline J, Grasby P, Williams S, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. Neuroimage. 1995;2(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19(3):1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brett M, Anton J-L, Valabregue R, Poline J-B. Region of interest analysis using the MarsBar toolbox for SPM 99. Neuroimage. 2002;16(2):S497. [Google Scholar]

- 65.McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Johnson SC. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips ML, Travis MJ, Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ. Medication effects in neuroimaging studies of bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Almeida JR, Mechelli A, Hassel S, Versace A, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML. Abnormally increased effective connectivity between parahippocampal gyrus and ventromedial prefrontal regions during emotion labeling in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;174(3):195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hassel S, Almeida JR, Kerr N, Nau S, Ladouceur CD, Fissell K, Kupfer DJ, Phillips ML. Elevated striatal and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity in response to emotional stimuli in euthymic bipolar disorder: no associations with psychotropic medication load. Bipolar disorders. 2008;10(8):916–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ellard KK, Zimmerman JP, Kaur N, Van Dijk KRA, Roffman JL, Nierenberg AA, Dougherty DD, Deckersbach T, Camprodon JA. Functional connectivity between anterior insula and key nodes of frontoparietal executive control and salience networks distinguish bipolar depression from unipolar depression and healthy controls Biological psychiatry: cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2018; 3(5):473–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pompei F, Dima D, Rubia K, Kumari V, Frangou S. Dissociable functional connectivity changes during the Stroop task relating to risk, resilience and disease expression in bipolar disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;57(2):576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pompei F, Jogia J, Tatarelli R, Girardi P, Rubia K, Kumari V, Frangou S. Familial and disease specific abnormalities in the neural correlates of the Stroop Task in Bipolar Disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):1677–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang J, Xie S, Guo X, Becker B, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Jiang T. Correspondent Functional Topography of the Human Left Inferior Parietal Lobule at Rest and Under Task Revealed Using Resting-State fMRI and Coactivation Based Parcellation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38(3):1659–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008;58(3):306–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seghier ML. The angular gyrus: multiple functions and multiple subdivisions. Neuroscientist. 2013;19(1):43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(2):189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Relative effectiveness of emotion induction procedures and the role of personal relevance in a clinical sample: a comparison of film, images, and music. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34(2):232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.