Abstract

The methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha, known as a non-conventional yeast, is used for the last 30 years for the production of recombinant proteins, including enzymes, vaccines, and biopharmaceuticals. Although a large number of reviews have been published elucidating the applications of this yeast as a cell factory, the latest was released about 10 years ago. Therefore, this review aimed at summarizing available information on the use of H. polymorpha as a host for recombinant protein production in the last decade. Examples of chemicals and virus-like particles produced using this yeast also are discussed. Firstly, the aspects that feature this yeast as a host for recombinant protein production are highlighted including the techniques available for its genetic manipulation as well as strategies for cultivation in bioreactors. Special attention is given to the novel genomic editing tools, mainly CRISPR/Cas9 that was recently established in this yeast. Finally, recent examples of using H. polymorpha as an expression platform are presented and discussed. The production of human Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and Staphylokinase (SAK) in H. polymorpha are described as case studies for process establishment in this yeast. Altogether, this review is a guideline for this yeast utilization as an expression platform bringing a thorough analysis of the genetic aspects and fermentation protocols used up to date, thus encouraging the production of novel biomolecules in H. polymorpha.

Keywords: Hansenula polymorpha, recombinant protein, methylotrophic yeast, genomic editing, bioprocess

Introduction

Over the years, the use of unicellular microorganisms as cell factories to obtain recombinant proteins became consolidated (Kim et al., 2015a). Recombinant DNA techniques allow the introduction of foreign genes in a host organism for the production of heterologous proteins biologically actives. Within this context, the choice of the host organism is crucial, since the functionality, solubility, and activity of the protein must be preserved during its synthesis (Vaquero et al., 2015). Yeasts are commonly used for the heterologous production of proteins, especially those that require post-translational modifications for proper folding since these modifications occur less frequently in prokaryotes.

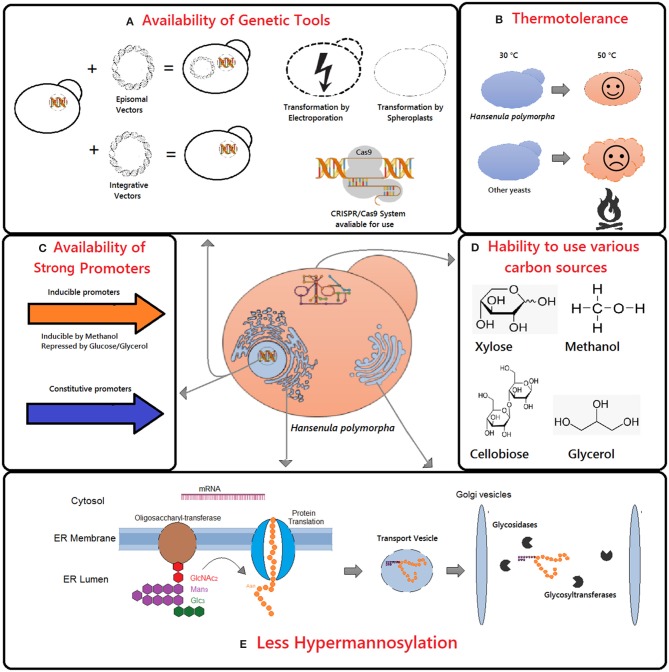

The H. polymorpha is commonly employed as an expression platform because of its unique characteristics (Figures 1A–E). It is thermotolerant and capable of growing at temperatures ranging from 30 to 50°C (Figure 1B). This capability is advantageous regarding mammalian protein production such as those requiring the 37°C temperature to preserve its biological activity (Van Dijk et al., 2000). Moreover, the presence of protein glycosylation pathway in H. polymorpha allows the production of eukaryotic recombinant proteins biologically active. Additionally, unlike other yeasts, it adds fewer sugar residues to the protein core, avoiding hyperglycosylation of recombinant proteins (Figure 1E). Finally, H. polymorpha is capable of using methanol as a carbon source which allowed the isolation of strong methanol inducible promoters (Figure 1C). Besides, it can utilize other carbon sources such as glycerol, glucose, xylose, and cellobiose (Ryabova et al., 2003) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Main advantages of Hansenula polymorpha as chassi for recombinant protein production include the availability of genetic tools (A,C), thermotolerance (B), ability to use various carbon sources (D), and glycosylation pattern (E).

Three parental strains with distinct origins of H. polymorpha are frequently used for recombinant protein production. The DL-1 strain (NRRL-Y-7560; ATCC26012) was isolated and characterized from soils samples (Levine and Cooney, 1973). The CBS4732 strain (CCY38-22-2; ATCC34438, NRRL-Y-5445) was isolated in irrigated soils in Pernambuco, Brazil (Morais and Maia, 1959). These two strains are mostly employed for industrial use. Lastly, the NCYC495 strain (CBS1976; ATAA14754, NRLL-Y-1798) is commonly used in the laboratory and was isolated at Florida from concentrated orange juice (Wickerham, 1951). Phylogenetic analysis showed that H. polymorpha appears to be two different species: Ogataea polymorpha and Ogataea parapolymorpha (Kurtzman and Robnett, 2010; Suh and Zhou, 2010). The strain NCYC495 and CBS4732 are closely related and renamed as O. polymorpha, whereas DL-1 strain is phylogenetically distant and reclassified as O. parapolymorpha. To avoid misunderstanding, the nomenclature H. polymorpha will be used in this review once both species share all characteristics elucidated in Figure 1.

Various studies focused on genetically modifying H. polymorpha strains for the production of several recombinant proteins (Gellissen et al., 1992; Hollenberg and Gellissen, 1997; Stöckmann et al., 2009). Later on, the advances in genomic-editing tools, optimization of transformation and cultivation protocols have led to the industrial development of H. polymorpha-based processes for the production of various pharmaceuticals. Currently, three commercially available Hepatitis B vaccines are produced using antigens derived from fermentative processes with H. polymorpha: HepavaxGene® (Johnson & Johnson), Gen Vax B® (Serum Institute of India) and Biovac-B® (Wockhardt) (http://www.dynavax.com/about-us/dynavax-gmbh/). Moreover, biopharmaceuticals successfully produced in this yeast and already available in the market included hirudin (Thrombexx®, Rhein Minapharm), insulin (Wosulin®, Wockardt) and IFNa-2a Reiferon® (Rhein Minapharm) (Gellissen et al., 2005).

It is noteworthy that the last published review of bioprocess development at H. polymorpha was nearly 10 years ago (Stöckmann et al., 2009). Thus, this review brings up to date strategies and examples of using this yeast as a host for recombinant protein production. The focus will be given on the studies developed in the last decade and are summarized in Table 1. The relevance of this yeast for the production of recombinant proteins, especially those for human welfare, justifies this literature update. Besides, newly genomic tools developed in the past years which have improved genetic manipulation of H. polymorpha are also discussed.

Table 1.

Recombinant proteins produced in the last decade using H. polymorpha as host.

| Protein | Maximum production | Promoter | Utilized carbon source | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human serum albumin (HSA) | 5.8 g/L | MOX | Glycerol/Methanol | Youn et al., 2010 |

| Heat shock protein gp96 | ≈150 mg/L | FMD | Methanol | Li et al., 2011 |

| Ferritin (FTH1) | 1.9 g/L | FMD | Glycerol/Methanol | Eilert et al., 2012 |

| Bacteriocin enterocin A (EntA) | 4.8 μg/mL | TEF1 (Arxula adeninivorans) | Glucose | Borrero et al., 2012 |

| Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) | ND | FMD | Methanol | Talebkhan et al., 2016 |

| Streptavidin (SAV) | ≈751 mg/L | FMD | Methanol | Wetzel et al., 2016 |

| Human parathyroid hormone (PTH) fragment 1–34 | 150 mg/L | FMD | Glycerol/Methanol | Mueller et al., 2013 |

| Penicillin | 1.1 μg/mL | MOX | Glucose/Methanol | Gidijala et al., 2009 |

| Human papilomavirus 16 L1 Protein (HPV16L1) | 78.6 mg/L | MOX | Methanol | Li et al., 2009 |

| HPV type 16 L1-L2 chimeric protein (SAF) | 132.10 mg/L | MOX | Methanol | Bredell et al., 2018 |

| Rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) | 14.6 mg/L | FMD | Glycerol | Qian et al., 2013 |

| Hepatitis B virus PreS2-S antigen | 250 mg/L | MOX | Methanol | Xu et al., 2014 |

| Human papillomavirus Type 52 L1 Protein (HPV 52 L1) | ND | MOX | Methanol | Liu et al., 2015 |

| Rotavirus VP6 protein (RV VP6) | 3350.71 mg/L | MOX | Methanol | Bredell et al., 2016 |

| Hepatitis E virus-like particles (HEV VLPs) | 1.0 g/L | MOX | Methanol | Su et al., 2017 |

| Uricase from Candida utilis | 52.3 U/mL | MOX | Methanol | Chen et al., 2008 |

| Lipase from Yarrowia lipolytica (YlLip11) | 1,144 U/L | TEF1 (Arxula adeninivorans) | Glucose | Kumari et al., 2015 |

| T4 lysozyme | 0.49 g/L | Not used | Glycerol | Wang et al., 2011 |

| Staphylokinase (SAK) | 1,212 mg/L | FMD | Glycerol/Methanol | Moussa et al., 2012 |

ND, Not Determined.

Why Use H. polymorpha as Host for Heterologous Expression?

The advantages of H. polymorpha for industrial processes comprise high-cell-density fermentation, capacity to utilize low-cost substrates, an established defined synthetic media, status GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) and consolidated strategies for cultivation in bioreactors (Jenzelewski, 2002). This yeast features genome-editing tools available for genetic manipulation (Figure 1A). An efficient protocol for transformation by electroporation has been described previously (Faber et al., 1994) as well as protocols for transforming protoplast ((Tikhomirova et al., 1988)). Among them, the electroporation method is more efficient than the protoplast, yielding 1.7 × 106/μg plasmid DNA vs. 2 to 3 × l04/μg DNA. The lithium acetate-dimethyl sulfoxide method has also been used tested (Sohn et al., 1999; Heo et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2015b). Furthermore, a method using nanoscale carriers for DNA delivery was employed for the transformation of H. polymorpha with twice efficiency of those obtained by electroporation and 15-fold for LiAc/DMSO method (Filyak et al., 2013). Moreover, three independent research groups have recently developed the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing tool for H. polymorpha (Numamoto et al., 2017; Juergens et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). Finally, the three strains of H. polymorpha had its genome sequenced, DL-1 (Ravin et al., 2013), NCYC495 (Riley et al., 2016), and CBS4732 (Ramezani-Rad et al., 2003).

Strategies for heterologous protein production in H. polymorpha take advantage of the yeast ability to grow in the presence of methanol. The methanol inducible promoters, formate dehydrogenase (FMD), and methanol oxidase (MOX) are the most utilized in genetic engineering strategies as it can be seen in Table 1. Shifting to methanol-feed led to upregulation of genes involved in its catabolism, for example the FMD gene was approximately 350-fold upregulated, while the MOX and DHAS genes were 17.3 and 19-fold upregulated when compared to growth on glucose (van Zutphen et al., 2010). Although an upregulation does not necessarily indicate a high promoter activity, other studies have shown that in the presence of methanol the MOX and FMD promoters present an enhanced activity (Amuel et al., 2000; Suppi et al., 2013).

The methanol-inducible promoters are not present only in H. polymorpha but in all methylotrophic yeasts. For instance, the well-known yeast Pichia pastoris (recently renamed as Komagataella sp.) is the yeast host more utilized for recombinant protein production. Although P. pastoris also has methanol-inducible promoters, the advantage of using H. polymorpha is that some of them are derepressed in the presence of glycerol which is less pronounced in P. pastoris (60–70% vs. 2–4% of induced levels) (Hartner and Glieder, 2006; Vogl and Glieder, 2013). In a comparative study, The Kunitz-type protease inhibitor (KPI) encoding gene was inserted in H. polymorpha and P. pastoris under the control of the alcohol oxidase, AOX1 promoter (Raschke et al., 1996). For both yeasts, no mRNA encoding for KPI was detected when the cells were cultured in glucose as the carbon source but were abundant when induced by methanol. However, when cells grew in glycerol, it was possible to detect KPI only in H. polymorpha. Therefore, the derepression of methanol inducible promoters is a favorable feature of H. polymorpha over other methylotrophic yeasts.

Additionally, H. polymorpha is thermotolerant while P. pastoris is not (Figure 1B). The increase in temperature does not imply a higher yield of the recombinant protein but is relevant in industrial processes since it reduces microbial contamination and cooling costs (Abdel-Banat et al., 2010). Also, higher temperatures facilitate the implementation of Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) since the thermal resistance allows the utilization of thermophilic hydrolases (Voronovsky et al., 2009). The EGII gene encoding endoglucanase II from Trichoderma reesei was produced in both methylotrophic yeasts, and the recombinant proteins were characterized. Although the secreted enzymes showed optimum activity at the same temperature (75°C), the one produced by H. polymorpha was shown to be more thermostable while remaining active after incubation at high temperatures (60–80°C) (Akbarzadeh et al., 2013).

If the recombinant protein is to be produced under the control of a methanol inducible promoter, the cultivation in the bioreactor is performed in a two-step. Initially, the growth phase is performed using glucose or glycerol as a carbon source in batch cultures. Then, the induction phase is accomplished by feeding the bioreactor with methanol or methanol/glycerol mixtures that can be added continuously or in pulses. For instance, the production of ferritin in H. polymorpha using a methanol and glycerol mixture (4:1) during the induction phase resulted in 1.9 g L of the recombinant protein (Table 1) (Eilert et al., 2012). In the case of the rabies virus glycoprotein production, only glycerol was employed during the induction phase (Qian et al., 2013). Despite the low levels achieved (14.6 mg/L), this is an example that glycerol can be used in both the growth and induction phases of this yeast. Although these two strategies are feasible to control recombinant protein production, the most common strategy employed is induction using only methanol 0.5–1% (Table 1).

A disadvantage of using such methanol inducible promoters is their repression caused by the presence of glucose in the media, although the derepression has already been reported (Mayer et al., 1999). In this point of view, H. polymorpha strains deficient in glucose repression represent alternative platforms for recombinant protein production (Krasovska et al., 2007). These mutants have a knock out at the GCR1 gene that encodes a hexose transporter with altered activity leading to several alterations in the cell metabolism, including the derepression of methanol-related genes in the presence of glucose (Stasyk et al., 2004). Thus, the methanol-induced promoters controlling the recombinant protein production might be induced by either methanol or glucose. The H. polymorpha gcr1 mutants are commonly utilized as the bio-elements for Yeast-based biosensing. Some practical examples of these biosensors utilization include the detection of L-lactate (Smutok et al., 2007), urate (Dmytruk et al., 2011), formaldehyde (Sigawi et al., 2014), and D-lactate (Smutok et al., 2018).

Some H. polymorpha-based platforms utilize the strong constitutive promoter GAP instead of methanol-inducible ones (Heo et al., 2003). The use of this promoter for the construction of recombinant strains, as well as gcr1 mutants, enables the production of proteins without the addition of methanol. Since this molecule is flammable and toxic, avoiding its use can be advantageous. Indeed, several studies developing H. polymorpha strains for bioethanol production utilize genes under the control of the GAP promoter (Kurylenko et al., 2014, 2018). Examples of the utilization of the H. polymorpha GAP promoter included the development of thermotolerant strains, improvement of xylose utilization and those capable of Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) as recently reviewed (Dmytruk et al., 2017).

Another advantage of using H. polymorpha as a host for recombinant protein production is its glycosylation pattern (Figure 1E). The yeasts frequently hyperglycosylate recombinant proteins. However, the intensity and type of sugar added dependent on both the organism and the sequence of the heterologous protein. The production of a recombinant glucose oxidase of Aspergillus niger was attempted using both yeasts H. polymorpha and S. cerevisiae (Kim et al., 2004). It has been shown that in H. polymorpha 27% less glycosylation was observed. Also, antibody anti-α1,3-mannose did not recognize the protein produced by H. polymorpha but was positive for that originated from S. cerevisiae which indicates that in H. polymorpha the recombinant protein was not immunogenic (Ballou, 1990). In the following years, efforts were made to develop engineered strains with human-pattern glycosylation (Kim et al., 2006; Oh et al., 2008; Cheon et al., 2012). These strains lack essential genes which encode enzymes for hypermannosylation pathways such as α-1,6-mannosyltransferase (Δhpoch1) and dolichyl-phosphate-mannose dependent α-1,3-mannosyltransferase (Δhpalg3) beside their has the human gene encoding β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GNTI). The null mutants were able to produce human hybrid-type N-glycans (Cheon et al., 2012). Therefore, all the knowledge acquired about the physiology, metabolism, and genetics of this yeast enables its utilization as a host for heterologous protein production.

The H. polymorpha Genetic Engineering Tools

The viability of tools for fast and precise genome edition is crucial for the development of the expression platforms. Some methods for the genetic manipulation of H. polymorpha have already been described, both for gene introduction and deletion (Figure 1A). It has been previously reported that episomal plasmids are mitotically unstable in H. polymorpha (Bogdanova et al., 1995, 2000) and consequently are not suitable for the development of industrial strains. Episomal plasmids contain the H. polymorpha autonomous replicating sequences (HARS) derived from subtelomeric regions (Sohn et al., 1996). Nevertheless, the HARS sequences do not guarantee stability for circular plasmids. Thus, the prolonged incubation in selective medium forces the plasmid integration usually in the respective subtelomeric locus (Kim et al., 2003). Hence, the integrative plasmids are most suitable for genetic manipulation of H. polymorpha. Depending on the locus of integration it is possible to reach between 1 up to 100 copies into the genome (Agaphonov et al., 1999).

The H. polymorpha integration plasmids (pHIP) series have several promoters and selective markers (For detailed information see (Saraya et al., 2012). They show an easy terminology in which the letter indicates the selective marker and the number indicates the promoter. For example, the pHIPH15, the “HIP” means “Hansenula Integration plasmid” while the letter stands for the selective marker, in this example hygromycin. The number indicates the promoter utilized in the plasmid and “15” is for DHAS. There are fifteen H. polymorpha promoters available in the pHIP series (https://www.rug.nl/research/molecular-cell-biology/research/the-hansenula-polymorpha-expression-system), and the site-specific integration is driven by linearization in the promoter region of the plasmid. For selection, auxotrophic and dominant markers can be used. They include Sc LEU2, Hp URA3, Hp ADE11, Hp MET6, Sh-ble (Zeocine), Sn-nat1 (Nourseothricin), Kp-hph (Hygromycin B), and Tn-KanMX (G418/Geneticin) (Saraya et al., 2012). Another possibility for the introduction of an exogenous gene in H. polymorpha is the wide-range vector CoMed™ system (Böer et al., 2007). This vector was designed to fit in many species of yeast, enabling to save time and effort during the cloning procedure. The vector contains ARS and rDNA sequences that drive the integration of the plasmid into H. polymorpha genome. Besides, it was constructed in modules flanked by recognizing sites of restriction enzymes that allows the exchange of expression cassettes and selective markers.

Gene deletion in H. polymorpha is reached through the construction of cassettes containing a homologous region of the gene to be deleted flanking 5′ and 3′ of the target locus. Usually, the cassette has an antibiotic as a selection marker such as zeocin or hygromycin. Although there are different approaches for gene deletion in H. polymorpha, the disruption frequencies are of approximately 35% with homology arms ranging from 500 to 1,000 bp (Table 2). The deletion cassettes can be constructed by single-step PCR as an adaptation of the protocol previously utilized in S. cerevisiae (Manivasakam et al., 1995). A one-step mediated-PCR method for gene disruption was also previously reported (Gonzalez, 1999). As a proof concept, the gene YNR1 of H. polymorpha strain NCYC495 (ura3) was disrupted utilizing a construct bearing the URA3 auxotrophic marker flanked by homologous regions to the target gene. The homologous arms 5‘ and 3‘ tested varied between 25 and 1,000 bp in size with the best results obtained with the larger homology (35%). Similar results were observed in the disruption of MOX gene (36%) with 1,000/1,000 homologous arm size (Gonzalez, 1999) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Most common techniques used for gene deletion in H. polymorpha.

| Target locus | Strain | Frequency of Deletion % | Method | Homologous arm size (5′/3′) bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YNR1 | NCYC495 | 35 | Deletion cassette | 1,000/1,000 | Gonzalez, 1999 |

| MOX | NCYC495 | 36 | Deletion cassette | 1,000/1,000 | |

| MOX | NCYC495 Δyku80 | 88 | Deletion cassette | 245/247 | Saraya et al., 2012 |

| MOX | NCYC495 | 31 | Deletion cassette | 245/247 | |

| ALG3 | NCYC495 | 35 | Deletion cassette | 491/520 | Qian et al., 2009 |

| ALG3 | NCYC495 | 76 | Co-transformation with single-stranded DNA | 491/520 | |

| ALG3 | NCYC495 | 19 | Deletion cassette | ~250/250 | |

| ALG3 | NCYC495 | 33 | Co-transformation with single-stranded DNA | ~250/250 |

In another study, the deletion cassettes were designed containing flanking regions with different lengths for targeting MOX locus. In size, the homologous arms were tested between 30 and 250 bp. The deletion frequency for fragments of up to 50 bp was only ±12%. The larger homologous arm tested showed an incidence of 31% (Table 2). Another strategy adopted was the deletion of ku80 aiming at increasing the deletion frequency (Saraya et al., 2012). This gene deletion increases the repair by homologous recombination (HR) instead of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), ensuring site-specific integration. The Δyku80 strain was generated by replacing this gene with the URA3 gene. For cassettes designed to target in MOX gene with Hygromycin B as selection marker and flanking regions approximately 250 bp, the deletion efficiency was 88% in Δyku80 strain vs. 31% in the wild-type (Table 2).

The limited number of available markers can impair multiple gene insertion or deletion. Therefore, recycling the selective markers using the Cre–loxP recombination technique has been applied in H. polymorpha (Qian et al., 2009; Agaphonov and Alexandrov, 2014). The gene PMC1 encoding for the protein Calcium-transporting ATPase 2 was disrupted in the strain DL1-L (leu2) using auxotrophic marker LEU2. The MOX promoter drives the CRE gene expression, so when methanol was added into the cultivation medium, the cassette contained the marker LEU2 was excised from the genome. Furthermore, these clones were unable to grow in the presence of CaCl2 corroborating the PMC1 deletion. The combination of different approaches was utilized to increase the efficiency for gene deletion in H. polymorpha NCYC495 (Qian et al., 2009). The knock-out system uses a sticky-end polymerase chain reaction method for the construction of deletion cassettes, LiAc/single-stranded (SS)-DNA/PEG for cell transformation and loxP-flanked selective markers for multiple deletions. The main advantage of this approach is the use of single-stranded DNA for co-transformation with deletion cassettes. Two genes were targeted, URA5 and ALG3, encoding the orotate-phosphoribosyl transferase (OPRTase) and alpha-1,3-mannosyltransferase, respectively. The cassette bearing loxP-kanMX-loxP with ~500 bp or ~250 bp homologous arms were co-transformed with and without single-stranded DNAs. For gene ALG3, the frequency of homologous recombination increased from 19 to 33% with ~250 bp homologous arms in the presence of single-stranded DNA (Table 2). When 500 bp homology regions were utilized, the frequency raised from 35 to 76% for co-transformation with single-stranded DNA (Table 2). The same pattern was observed for the URA5 locus, for 250 bp 17% and 500 bp 31% without co-transformation while in the presence of single-stranded DNA were 32 and 73%, respectively (Qian et al., 2009).

At present, the CRISPR/Cas9 technologies have been applied in various organisms aiming at genome edition by the promise of being more rapid and low cost than previously available technologies [see details in Donohoue et al. (2018)]. Three studies already reported the use of CRISPR/Cas9 in H. polymorpha (Table 3). In the first one, the locus ADE2 in the NCYC495 was targeted due to the red-phenotype that can be easily visualized upon successful deletion (Numamoto et al., 2017). For that, an episomal plasmid expressing both Cas9 and gRNA guided by the promoters ScTEF1 and OpSNR6, respectively was introduced in H. polymorpha. In the absence of the ADE2 DNA donor, the deletion frequency was around 10−3. When a DNA donor with 60/60 bp of homologous arms for ADE2 locus was co-transformed with Cas9 and gRNAADE2, it increased the efficiency by up to 47%. To evaluate the system efficiency in another locus, the loci ADE8 and PHO8 were disrupted resulting in 0.36 and 0.08% efficiencies, respectively. Aiming at improving the CRISPR/Cas9 system in this yeast, the promoters guiding Cas9 and gRNA were substituted for OpTDH3 and tRNA promoters, respectively. The cells were then transformed with these plasmids into two combinations: ScTEF1 (Cas9) and tRNA (gRNAADE2) promoters and OpTDH3 (Cas9) and tRNA (gRNAADE2) promoters. Without the DNA donor, the first combination reached a frequency of 38% whiles the second one 45% for the locus ADE2. Finally, the improved system in that OpTHD3 promoter guide the Cas9 expression and the tRNA promoter the gRNA expression was used for deletion of three genes from phosphate signal transduction (PHO) pathway, PHO1, PHO11, and PHO84. In this case, more than one gRNA was tested for each locus, and no DNA donor was utilized. Four gRNAs were designed for the PHO1 gene, however, in 2 of them, the disruption efficiency was 0% while for another two 50, and 71% were observed. For the locus PHO11, one of three showed 0% of disruption and 17 and 30% for the other gRNAs. The last locus targeted PHO84 obtained the same frequency of approximately 67% for both two gRNAs utilized (Numamoto et al., 2017).

Table 3.

CRISPR/Cas9 systems available for genomic editing in H. polymoprha.

| Strain | Cas9 Promoter | Cas9 origin | sgRNA Promoter | gRNA tested per target | Cas9 and gRNA in the same plasmid? | Plasmid type | target locus | % deletion efficiency | DNA donor (5′/3′)bp | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCYC495 | TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | Homo sapiens | SNR6 (H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 10−3 | No | Numamoto et al., 2017 |

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | Homo sapiens | SNR6 (H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 47 | Yes (60/60)bp | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | Homo sapiens | SNR6 (H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE8 | 0.36 | No | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | Homo sapiens | SNR6 (H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | PHO8 | 0.08 | No | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | Homo sapiens | tRNACUG(H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 38 | No | ||

| TDH3 (H. polymorpha) | Homo sapiens | tRNACUG(H. polymorpha) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 45 | No | ||

| TDH3 (H. polymorpha) | Homo sapiens | tRNACUG(H. polymorpha) | 4 | Yes | Episomal | PHO1 | 71 | No | ||

| TDH3 (H. polymorpha) | Homo sapiens | tRNACUG(H. polymorpha) | 3 | Yes | Episomal | PHO11 | 30 | No | ||

| TDH3 (H. polymorpha) | Homo sapiens | tRNACUG(H. polymorpha) | 2 | Yes | Episomal | PHO84 | 67 | No | ||

| DL-1 | TEF1 (Arxula adeninivorans) | iCas9 | TDH3 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 63 ± 2 | ND | Juergens et al., 2018 |

| TEF1 (Arxula adeninivorans) | iCas9 | TDH3 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 and YNR1 | 2-5 | ND | ||

| CBS4732 | TEF1 (Arxula adeninivorans) | iCas9 | TDH3 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | Yes | Episomal | ADE2 | 9 ± 1 | ND | |

| Laboratory strain CGMCC7.89 | TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | LEU2 | 58.33 ± 7.22 | Yes (1,000/1,000)bp | Wang et al., 2018 |

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | URA3 | 65.28 ± 2.41 | Yes (1,000/1,000)bp | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | ADE2 | 62.18 | Yes (1,000/1,000)bp | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | ADE2 | 37.18 | Yes (500/500)bp | ||

| TEF1 (S. cerevisiae) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | URA3, LEU2 and HIS3 | 23.61 | Yes (1,000/1,000)bp | ||

| MOX (H. polymorpha) | iCas9 | SNR52 (S. cerevisiae) | 1 | No | Integrative | rDNA | 75 | Yes (1,000/1,000)bp |

ND* No difference was observed in deletion efficiency with or without HR donor.

In another study, the CRISPR/Cas9 was used for genome edition in both Kluyveromyces lactis and Ogataea sp. In the last one, the utilized strains were CBS4732 and DL-1 (Juergens et al., 2018). The AaTEF1 promoter was used to guide a Cas9 variant with higher activity, known as improved Cas9 (iCas9) (Bao et al., 2015). The promoter ScTDH3 was used to control the gRNA expression. The ADE2 locus also was disrupted with the same gRNA for both strains O. polymorpha (CBS 4732) and O. parapolymorpha (DL-1). The disruption frequencies varied between the two species which may indicate that even in phylogenetically close species the efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas9 system may require adjustments. The red phenotype, expected for colonies whose ADE2 was deleted, just appeared after prolonged incubation time with disruption rates of 9% for O. polymorpha while O. parapolymorpha showed ~61 and 63% after 96 and 192 h of incubation, respectively. Surprisingly, the utilization of marker-free DNA donor did not affect the deletion efficiency in this case. Also, a multiple gene editing for multi-locus targeting was employed in this study. A plasmid carrying gRNAs targeting the loci ADE2 and YNR1 was utilized simultaneously for gene disruption. The gRNAs were placed in a tandem array spaced by a 20-bp linker. Although the deletion frequencies reached values between only 2 and 5%, this was the first report of multiple genes editing in H. polymorpha through CRISPR/Cas9 (Juergens et al., 2018).

Recently, an efficiently multiplex system was employed using a laboratory strain CGMCC7.89 (from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center) as host (Table 3). The plasmids carrying the Cas9 and gRNA were inserted into the genome to ensure their stability through up- and downstream homologous arms (~1.5 kb). The Cas9 was integrated into the MET2 locus while and the gRNA into the ADE2 locus. The positive clones were selected by the respective auxotrophies. All transformations were performed with the presence of donor DNA consisting of a fragment containing the up- and downstream region of the target gene amplified from the H. polymorpha genome. Initially, the LEU2 and URA3 were targeted to test the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Successful deletion occurred with 58.33 ± 7.22% for LEU2 and 65.28 ± 2.41% for URA3. The effect of the size of the homology arms was tested using the ADE2 locus flanking regions from 50 to 1,000 bp. When 50 bp was utilized, the efficiency was 0%, for 500 and 1,000 bp the values obtained were 37.18 and 62.18%, respectively. Therefore, all editing templates used for subsequent experiments had 1,000/1,000 bp of homology. These results corroborate the hypothesis that for H. polymorpha at least 500 bp are required to ensure deletion efficiency. The competence for multiple simultaneous deletions was verified with an efficiency of 23.61% for three loci URA3, LEU2, and HIS3. Next, a template containing a gfpmut3a expression cassette flanked by up- and downstream homologous arms of the three loci, URA3, LEU2, and HIS3, were used separately as DNA donor to prove that gene insertion was feasible using CRISPR/Cas9. The efficiency of integration observed reached 66.7%, 66.7% and 62.50% for HIS3, URA3, and LEU2, respectively. After that, the gfpmut3a was replaced by genes encoding the proteins within the resveratrol metabolic pathway that resulted in maximum production of 4.7 mg/L. The effect of gene copy number required for resveratrol synthesis was tested by multiple integrations into rDNA regions using CRISPR/Cas9. In this strategy, the TEF1 promoter that was driving the expression of the CAS9 encoding gene was replaced by the methanol inducible MOX. In the presence of the gfpmut3a cassette with homologous arms, its insertion in the rDNA region occurred with a frequency of 75% and 11 copies of gfpmut3a were quantified in one of the studied clones. Finally, this approach was used to introduce the three genes that enable resveratrol synthesis in this yeast. The maximum resveratrol production was 97.23 ± 4.84 mg/L in a strain containing nine copies of each gene (Wang et al., 2018).

Examples of Recombinant Proteins in H. polymorpha

The latest recombinant proteins that utilize H. polymorpha as host are summarized in Table 1 although, up to this moment, none of the listed examples were performed at industrial scale. The first heterologous protein produced in H. polymorpha was the surface antigens from hepatitis B virus (Janowicz et al., 1991). Furthermore, H. polymorpha, has been extensively used for the production of Virus-like particle (VLP), which are viral proteins that can be used for the development of vaccines (Kumar and Kumar, 2019). Only in the last decade, H. polymorpha was used to produce VLPs for the hepatitis B virus (Li et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2014), hepatitis C virus (He et al., 2008), hepatitis E virus (Su et al., 2017), Human papillomavirus (Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2015; Bredell et al., 2018), rabies virus (Qian et al., 2013), and rotavirus (Bredell et al., 2016). Recently, a chimeric VLP was development for H. polymorpha (Wetzel et al., 2018). In this type of platform, viral proteins are produced heterologously as chimeric proteins containing antigens from different viruses, allowing the simultaneous production of different VLPs. For H. polymorpha, the developed chimeric VLPs contained viral proteins from bovine viral diarrhea virus, the classical swine fever virus, the feline leukemia virus, and the west Nile virus, using as scaffold the small surface protein of the duck hepatitis B virus (Wetzel et al., 2018).

Further examples of recombinant proteins using H. polymorpha as host include the human Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and Staphylokinase (SAK). Here it is summarized how the recombinant strain was constructed, the process was optimized and scaled-up to 80 liters (Moussa et al., 2012; Mueller et al., 2013). The PTH is a hormone secreted by the parathyroid gland responsible for calcium homeostasis in the blood and osteogenesis. It is a glycoprotein, but it has already been shown that non-glycosylation does not affect its biological activity (Bisello et al., 1996). The N-terminal 1–34 fragment of this protein has an essential function as a receptor binding region and is employed for the treatment of osteoporosis (Cho et al., 2018). The integrative plasmid pFPMT-MFα containing the coding region for the 1–34 fragment of PTH fused with MFα signal was inserted into Δyps7 strain (deficient protease YPS7). The FMD promoter controlled the production of PTH, and the plasmid carried a HARS sequence for genomic integration (Kim et al., 2003). Positive clones for PTH production were selected for medium optimization on a micro-plate scale.

Using micro-scale assays, it has been possible to evaluate the influence of culture media on the PTH titers. At this stage, all standard complex media (YPD, YPG, YNB) in addition to two synthetic media Syn 6 and Syn 6-cp (supplemented with citrate and peptone) were tested. The best PTH concentration (~40 mg/L) was achieved with the Syn6-cp medium. After that, the influence of three peptones (soy, wheat, and potato) in a 100 mL shake scale was investigated with the highest production of the recombinant protein (9.6 mg/L) was achieved using wheat peptone. Next step was performed in 250 mL baffled flasks with 100 mL of working volume in fed-batch mode. Manual applications after 20, 24, 42, 46, and 50 h of inducing-mixture containing a methanol/glycerol (1:1) and wheat peptone resulted in 25.4 mg/L of PTH. In the following steps, 300-mL bioreactors were utilized to test these parameters under controlled fermentation conditions. Cell cultures were pre-grown in glycerol 3% for 24 h. After that, the induction phase was performed with methanol pulsed every 6 h during 24 h leading to the production of 68.3 mg/L of PTH. A similar result was obtained in 2 L reactors (67 mg/L) using the same strategy. Finally, 8 L and 80 L fermentation were performed using the optimum conditions. For that, the partial oxygen pressure (pO2) was set to 30%. The feeding strategy was changed from pulse-wise to feeding scheduled realized at a constant rate ranging from 20 to 60 g/L/h for 52 h. Using this fermentation strategy was obtained 120 mg/L and 150 mg/L PTH in 8 and 80 L, respectively (Mueller et al., 2013).

A similar approach has been used for the heterologous production of Staphylokinase (SAK), a biopharmaceutical with pro-fibrinolytic activity (Moussa et al., 2012). Recombinant strains producing an SAK THR164 variant (ThromboGenics NV) were developed and the process was scaled-up from micro-titer plates to 80 L. Two isoforms encoding the SAK protein, rSAK-1 and rSAK-2, were placed under control of the FMD promoter, in addition to containing the MFα1 sequence for secretion. The rSAK-2 had a substitution of the Thr-30 amino acid residue for an alanine. This is a recognition site for N-glycosylation and its mutation showed to affect the glycosylation pattern of the produced protein. The final plasmids bearing URA3 auxotrophic marker and containing the genes encoding rSAK-1 and rSAK-2 were transformed into the strain RB11, a uracil-auxotrophic variant of CBS4732. After the selection, the positives clones were tested for rSAK-1 and rSAK-2 production in shake flasks using YPG (glycerol). The Western blot assay demonstrated that r-SAK1 and not r-SAK-2 was glycosylated. Taking into account that glycosylated SAK shows reduction in enzymatic activity, only strains producing rSAK-2 were further utilized for process optimization.

The micro-plate assays were employed to evaluate the pH, medium and feeding strategy effects on rSAK-2 production using SYN6 medium as basis. The screening of pHs ranging 4–8, twenty different peptones and two feeding strategies indicated that the highest production of rSAK-2 (90 mg/L) occurred in pH 6.5 with SYN6 supplemented with wheat peptone and induced by methanol. Further medium optimization was realized in 500 mL shake flasks with a working volume of 100 mL. At this stage, variations of synthetic medium SYN6 were tested. The removal of trace elements and vitamins of SYN6 yielded 200 mg/L of rSAK-2 after 48 h of fermentation, the best production achieved in shake flasks. This medium was designed as SYN6.46d. After that, the process was transferred to 300 mL bioreactors where two feeding solutions were evaluated. The first one, named as FEED_1, contained 20% yeast extract (w/v), 10% peptone (w/v), 5% glycerol (w/v), and 10% methanol (w/v). While FEED_2 in turn was composed by 20% peptone (w/v), 10% glycerol (w/v), 20% yeast extract (w/v) and 10% methanol (w/v). In constant feeding mode (4 mL of feeding solution per hour) using FEED_2, the yield of rSAK-2 was 423 mg/L at 48 h of fermentation, the highest amount reached so far. Finally two parameters were adjusted before scaling-up the process from 300 mL bioreactors. The air flow was setting to 2 L/min instead 0.5 L/min and the stirring speed was changed from 500 rpm to 800 rpm. Lastly, fermentations using the medium SYN6.46d in a constant fed-batch mode with the feeding solution FEED_2 were performed at bioreactors of 2, 8, and 80 L that yielded rSAK-2 amounts of 1,212, 1,081, and 1,109 mg/L, respectively (Moussa et al., 2012).

Although H. polymorpha is more frequently used as host for recombinant protein, the production of chemicals and fatty acids has also been described. The most extensive example discussed in the literature is the utilization of H. polymorpha to produce ethanol using xylose as carbon source. Up to now the best reported strain achieved 12.5 g/L using a strain where CAT8 gene was disrupted. This gene encoding a transcriptional activator involved in the regulation of xylose metabolism in H. polymorpha (Ruchala et al., 2017). For an extensive review on this particular bioprocess the reader is directed to a recently published review (Dmytruk et al., 2017). Production of γ-linolenic acid was achieved in H. polymorpha by the introduction of Mucor rouxii Δ6-desaturase gene under control of the MOX promoter (Khongto et al., 2010). Despite the utilization of a methanol-inducible promoter, the maximum γ-linolenic acid titers, 697 mg/L, was reached when glycerol was used as the carbon source. For the production of 1,3-propandiol, all six genes necessary for its biosynthesis were transferred from Klebsiella pneumoniae (Hong et al., 2011). All inserted genes were present in one single plasmid under the control of the GAP promoter. The resulting strains produced 2.4 g/L and 0.8 g/L of 1,3-Propandiol using glucose and glycerol as substrate, respectively (Hong et al., 2011). Similarly, the insertion of four genes were introduced in H. polymorpha enabling the synthesis of 5-hydroxyectoine (Eilert et al., 2013). Nevertheless, in this study all genes were cloned in different plasmids, where each plasmid had upstream- and downstream regions amplified from the yeast genome to direct the integration and a unique selection marker. The resulting strain was able to achieve 2.8 g/L of 5-hydroxyectoine using methanol as the carbon source. Recently, CRISPR/Cas9 was utilized to introduce three genes (TAL, 4CL, and STS) required for the resveratrol synthesis in H. polymorpha (Wang et al., 2018). All genes were cloned into one expression cassette and integrated into the rDNA locus aiming at multiple copy integrations. The best producing strain contained 9 copies of each gene and was able to produce approximately 98 mg/L (Wang et al., 2018).

Conclusions

The development of new cell factories for the production of heterologous proteins that are scarce is the primary challenge of the 21st century. Advances in molecular genetics and cultivation techniques drive the growing number of new expression platforms. Among these, the yeast H. polymorpha stand out as host due to the presence of strongly methanol-inducible such as MOX and FMD promoters, the glycosylation pattern compatible with human glycoproteins, the thermotolerance capacity and it is able to use different carbon sources (Figures 1A–E). Furthermore, various genetic engineering tools and transformation protocols are established in this yeast. Nevertheless, the low frequency of homologous recombination in H. polymorpha delays the strain construction step. Many efforts were made to bypass this problem: utilization of ku80 strain, methods for construction of deletion cassettes and implementation of CRISPR/Cas9 technology.

Genome editing via CRISPR/Cas9 represents a powerful tool for genetic manipulation. It is possible to perform not only the deletion of endogenous genes from the organism but also the insertion of exogenous sequences into its genome. The three systems implemented in H. polymorpha allowed disruption or the introduction of exogenous genes. Furthermore, the utilization of episomal plasmids for CRISPR/Cas9 implementation in H. polymorpha required modifications into the initial strategy to enhance the deletion frequencies (Table 3). In both cases, adjustments to the developed approach increased the efficiency of the system: substitution of promoters (Numamoto et al., 2017) or prolonged incubation times to guarantee the activity of Cas9 (Juergens et al., 2018). Implementation of CRISPR/Cas9 through integrative plasmids guaranteed gene deletion rates >50% for different loci (Wang et al., 2018). Also, co-transformation with a DNA template to induce HR repair after slicing of Cas9 was more efficient than using only Cas9 and gRNA (Table 3). The CRISPR/Cas9 system was also efficient for the introduction of exogenous genes into H. polymorpha (Wang et al., 2018). It was possible to introduce a complete pathway for the synthesis of resveratrol in H. polymorpha in a single transformation event, representing a revolution in the genetic manipulation of this yeast. Thus, it is evident how the utilization of genome editing tools will reduce the time and cost of strain construction allowing a rapid introduction into the commercial scale.

Finally, the examples given for recombinant protein production can be extrapolated to the production of other molecules. Micro-scale cultivation is often used to optimize culture conditions by testing different mediums composition, pH and other factors that may affect the productivity of the desired protein. The best results are scaled up adding the feeding and oxygenation strategies. Altogether these features elucidated how H. polymorpha is a promising host for the establishment of various bioprocesses. This is reflected already by the number of products available in the market and by the pipeline of those that are in the optimization phase.

Author Contributions

JM-N wrote the manuscript. AG prepared the figure. NP assisted with writing, editing, and finalizing the manuscript. All authors approved its publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Brazilian funding agencies of Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) and FAP-DF.

References

- Abdel-Banat B. M. A., Hoshida H., Ano A., Nonklang S., Akada R. (2010). High-temperature fermentation: how can processes for ethanol production at high temperatures become superior to the traditional process using mesophilic yeast? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 861–867. 10.1007/s00253-009-2248-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaphonov M., Alexandrov A. (2014). Self-excising integrative yeast plasmid vectors containing an intronated recombinase gene. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 1048–1054. 10.1111/1567-1364.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaphonov M. O., Trushkina P. M., Sohn J. H., Choi E. S., Rhee S. K., Ter-Avanesyan M. D. (1999). Vectors for rapid selection of integrants with different plasmid copy numbers in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha DL1. Yeast 15, 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh A., Siadat S. O. R., Zamani M. R., Motallebi M., Barshan T. M. (2013). Comparison of biochemical properties of recombinant endoglucanase II of Trichoderma reesei in methylotrophic yeasts, Pichia pastoris and Hansenula polymorpha. Prog. Biol. Sci. 3, 108–117. 10.22059/PBS.2013.32100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amuel C., Gellissen G., Hollenberg C. P., Suckow M. (2000). Analysis of heat shock promoters in Hansenula polymorpha: the TPS1 promoter, a novel element for heterologous gene expression. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 5, 247–252. 10.1007/BF02942181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou C. E. (1990). Isolation, characterization, and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mnn mutants with nonconditional protein glycosylation defects. Methods Enzymol. 185, 440–470. 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85038-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z., Xiao H., Liang J., Zhang L., Xiong X., Sun N., et al. (2015). Homology-integrated CRISPR-Cas (HI-CRISPR) system for one-step multigene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 585–594. 10.1021/sb500255k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisello A., Greenberg Z., Behar V., Rosenblatt M., Suva L. J., Chorev M. (1996). Role of glycosylation in expression and function of the human parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor. Biochemistry 35, 15890–15895. 10.1021/bi962111+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böer E., Steinborn G., Kunze G. (2007). Yeast expression platforms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 77, 513–523. 10.1007/s00253-007-1209-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova A. I., Agaphonov M., Ter-avanesyan M. D. (1995). Plasmid reorganization during integrative transformation in Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast 11, 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova A. I., Agaphonov M. O., Ter-Avanesian M. D. (2000). Plasmid instability in methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha: the capture of chromosomal DNA fragments by replicative plasmids. Mol. Biol. 34, 36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero J., Kunze G., Jiménez J. J., Böer E., Gútiez L., Herranz C., et al. (2012). Cloning, production, and functional expression of the bacteriocin enterocin A, produced by Enterococcus faecium T136, by the yeasts Pichia pastoris, Kluyveromyces lactis, Hansenula polymorpha, and Arxula adeninivorans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5956–5961. 10.1128/AEM.00530-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredell H., Smith J. J., Görgens J. F., Zyl W. H. (2018). Expression of unique chimeric human papilloma virus type 16 (HPV-16) L1-L2 proteins in Pichia pastoris and Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast 35, 519–529. 10.1002/yea.3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredell H., Smith J. J., Prins W. A., Görgens J. F., van Zyl W. H. (2016). Expression of rotavirus VP6 protein: a comparison amongst Escherichia coli, Pichia pastoris and Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 16:fow001. 10.1093/femsyr/fow001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Wang Z., He X., Guo X., Li W., Zhang B. (2008). Uricase production by a recombinant Hansenula polymorpha strain harboring Candida utilis uricase gene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 79, 545–554. 10.1007/s00253-008-1472-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon S. A., Kim H., Oh D. B., Kwon O., Kang H. A. (2012). Remodeling of the glycosylation pathway in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha to produce human hybrid-type N-glycans. J. Microbiol. 50, 341–348. 10.1007/s12275-012-2097-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M., Han S., Kim H., Kim K. S., Hahn S. K. (2018). Hyaluronate–parathyroid hormone peptide conjugate for transdermal treatment of osteoporosis. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 29, 793–804. 10.1080/09205063.2017.1399001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmytruk K., Kurylenko O., Ruchala J., Ishchuk O., Sibirny A. (2017). Development of the thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha as efficient ethanol producer, in Yeast Diversity in Human Welfare, eds Satyanarayana T., Kunze G. (Singapore: Springer; ), 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dmytruk K. V., Smutok O. V., Dmytruk O. V., Schuhmann W., Sibirny A. A. (2011). Construction of uricase-overproducing strains of Hansenula polymorpha and its application as biological recognition element in microbial urate biosensor. BMC Biotechnol. 11:58. 10.1186/1472-6750-11-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoue P. D., Barrangou R., May A. P. (2018). Advances in industrial biotechnology using CRISPR-Cas systems. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 134–146. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilert E., Hollenberg C. P., Piontek M., Suckow M. (2012). The use of highly expressed FTH1 as carrier protein for cytosolic targeting in Hansenula polymorpha. J. Biotechnol. 159, 172–176. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilert E., Kranz A., Hollenberg C. P., Piontek M., Suckow M. (2013). Synthesis and release of the bacterial compatible solute 5-hydroxyectoine in Hansenula polymorpha. J. Biotechnol. 167, 85–93. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber K. N., Haima P., Harder W., Veenhuis M., Ab G. (1994). Highly-efficient electrotransformation of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Curr. Genet. 25, 305–310. 10.1007/BF00351482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filyak Y., Finiuk N., Mitina N., Bilyk O., Titorenko V., Hrydzhuk O., et al. (2013). A novel method for genetic transformation of yeast cells using oligoelectrolyte polymeric nanoscale carriers. Biotechniques 54, 35–43. 10.2144/000113980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellissen G., Janowicsz Z. A., Weydemann U., Melber K., Strasser A. W. M., Hollenberg C. P. (1992). High-level expression of foreign genes in Hansenula polymorpha. Biotechnol. Adv. 10, 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellissen G., Kunze G., Gaillardin C., Cregg J. M., Berardi E., Veenhuis M., et al. (2005). New yeast expression platforms based on methylotrophic Hansenula polymorpha and Pichia pastoris and on dimorphic Arxula adeninivorans and Yarrowia lipolytica—a comparison. FEMS Yeast Res. 5, 1079–1096. 10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidijala L., Kiel J. A. K. W., Douma R. D., Seifar R. M., van Gulik W. M., Bovenberg R. A. L., et al. (2009). An engineered yeast efficiently secreting penicillin. PLoS ONE 4:e8317. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C. (1999). One-step, PCR-mediated, gene disruption in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast 15, 1323–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner F. S., Glieder A. (2006). Regulation of methanol utilisation pathway genes in yeasts. Microb. Cell Fact. 5, 1–21. 10.1186/1475-2859-5-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Joshi S. B., Bosman F., Verhaeghe M., Middaugh C. R. (2008). Structural stability of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E1: effect of pH and dissociative detergents. J. Pharm. Sci. 98, 3340–3357. 10.1002/jps.21657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J. H., Hong W. K., Cho E. Y., Kim M. W., Kim J. Y., Kim C. H., et al. (2003). Properties of the Hansenula polymorpha-derived constitutive GAP promoter, assessed using an HSA reporter gene. FEMS Yeast Res. 4, 175–184. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00150-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg C. P., Gellissen G. (1997). Production of recombinant proteins by methylotrophic yeasts. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 8, 554–560. 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W. K., Kim C. H., Heo S. Y., Luo L. H., Oh B. R., Rairakhwada D., et al. (2011). 1,3-Propandiol production by engineered Hansenula polymorpha expressing dha genes from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 34, 231–236. 10.1007/s00449-010-0465-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz Z. A., Melber K., Merckelbach A., Jacobs E., Harford N., Comberbach M., et al. (1991). Simultaneous expression of the S and L surface antigens of hepatitis B, and formation of mixed particles in the methylotrophic yeast, Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast 7, 431–443. 10.1002/yea.320070502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenzelewski V. (2002). Fermentation and primary product recovery, in Hansenula polymorpha—Biology and Applications, ed Gellissen G. (Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim; ), 156–174. [Google Scholar]

- Juergens H., Varela J. A., Gorter de Vries A. R., Perli T., Gast V. J. M., Gyurchev N. Y., et al. (2018). Genome editing in Kluyveromyces and Ogataea yeasts using a broad-host-range Cas9/gRNA co-expression plasmid. FEMS Yeast Res. 18:foy012. 10.1093/femsyr/foy012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khongto B., Laoteng K., Tongta A. (2010). Fermentation process development of recombinant Hansenula polymorpha for gamma-linolenic acid production. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 1555–1562. 10.4014/jmb.1003.03004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Thak E. J., Lee D., Agaphonov M. O., Kang H. A. (2015b). Hansenula polymorpha Pmt4p plays critical roles in O-mannosylation of surface membrane proteins and participates in heteromeric complex formation. PLoS ONE 10:e0129914. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Yoo S. J., Kang H. A. (2015a). Yeast synthetic biology for the production of recombinant therapeutic proteins. FEMS Yeast Res. 15, 1–16. 10.1111/1567-1364.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. W., Kim E. J., Kim J.-Y., Park J.-S., Oh D.-B., Shimma Y., et al. (2006). Functional characterization of the Hansenula polymorpha HOC1, OCH1, and OCR1 genes as members of the yeast OCH1 mannosyltransferase family involved in protein glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6261–6272. 10.1074/jbc.M508507200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. W., Rhee S. K., Kim J. Y., Shimma Y. I., Chiba Y., Jigami Y., et al. (2004). Characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides assembled on secretory recombinant glucose oxidase and cell wall mannoproteins from the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Glycobiology 14, 243–251. 10.1093/glycob/cwh030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-Y., Sohn J.-H., Bae J.-H., Pyun Y.-R., Agaphonov M. O., Ter-Avanesyan M. D., et al. (2003). Efficient library construction by in vivo recombination with a telomere-originated autonomously replicating sequence of Hansenula polymorpha. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4448–4454. 10.1128/aem.69.8.4448-4454.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasovska O. S., Stasyk O. G., Nahorny V. O., Stasyk O. V., Granovski N., Kordium V. A., et al. (2007). Glucose-induced production of recombinant proteins in Hansenula polymorpha mutants deficient in catabolite repression. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 97, 858–870. 10.1002/bit.21284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Kumar P. (2019). Yeast-based vaccines: new perspective in vaccine development and application. FEMS Yeast Res. 19:foz007. 10.1093/femsyr/foz007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari A., Baronian K., Kunze G., Gupta R. (2015). Extracellular expression of YlLip11 with a native signal peptide from Yarrowia lipolytica MSR80 in three different yeast hosts. Protein Expr. Purif. 110, 138–144. 10.1016/j.pep.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman C. P., Robnett C. J. (2010). Systematics of methanol assimilating yeasts and neighboring taxa from multigene sequence analysis and the proposal of Peterozyma gen. nov., a new member of the Saccharomycetales. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 353–361. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylenko O. O., Ruchala J., Hryniv O. B., Abbas C. A., Dmytruk K. V., Sibirny A. A. (2014). Metabolic engineering and classical selection of the methylotrophic thermotolerant yeast Hansenula polymorpha for improvement of high-temperature xylose alcoholic fermentation. Microb. Cell Fact. 13:122. 10.1186/s12934-014-0122-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylenko O. O., Ruchala J., Vasylyshyn R. V., Stasyk O. V., Dmytruk O. V., Dmytruk K. V., et al. (2018). Peroxisomes and peroxisomal transketolase and transaldolase enzymes are essential for xylose alcoholic fermentation by the methylotrophic thermotolerant yeast, Ogataea (Hansenula) polymorpha. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11, 1–16. 10.1186/s13068-018-1203-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D. W., Cooney C. L. (1973). Isolation and characterization of a thermotolerant methanol-utilizing yeast. Appl. Microbiol. 26, 982–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., He X., Guo X., Zhang Z., Zhang B. (2009). Optimized expression of the L1 protein of human papilloma virus in Hansenula polymorpha. Chin. J. Biotech. 25, 1516–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Song H., Li J., Wang Y., Yan X., Zhao B., et al. (2011). Hansenula polymorpha expressed heat shock protein gp96 exerts potent T cell activation activity as an adjuvant. J. Biotechnol. 151, 343–349. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Yao Y., Yang X., Bai H., Huang W., Xia Y., et al. (2015). Production of recombinant human papillomavirus type 52 L1 protein in Hansenula polymorpha formed virus-like particles. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 936–940. 10.4014/jmb.1412.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manivasakam P., Weber S. C., Mcelver J., Schiestl R. H. (1995). Micro-homology mediated PCR targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 2799–2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A. F., Hellmuth K., Schlieker H., Lopez-Ulibarri R., Oertel S., Dahlems U., et al. (1999). An expression system matures: a highly efficient and cost-effective process for phytase production by recombinant strains of Hansenula polymorpha. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 63, 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais J. O. F., Maia M. H. D. (1959). Estudos de microorganismos encontrados em leitos de despejos de caldas de destilarias de Pernambuco. II. Uma nova especie de Hansenula: H. polymorpha. Anais de Escola Superior de Quimica de Universidade do Recife 1, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa M., Ibrahim M., El Ghazaly M., Rohde J., Gnoth S., Anton A., et al. (2012). Expression of recombinant staphylokinase in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. BMC Biotechnol. 12:96. 10.1186/1472-6750-12-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller F., Moussa M., El Ghazaly M., Rohde J., Bartsch N., Parthier A., et al. (2013). Efficient production of recombinant parathyroid hormone (rPTH) fragment 1-34 in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. GaBI J. 2, 114–122. 10.5639/gabij.2013.0203.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Numamoto M., Maekawa H., Kaneko Y. (2017). Efficient genome editing by CRISPR/Cas9 with a tRNA-sgRNA fusion in the methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 124, 487–492. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh D. B., Park J. S., Kim M. W., Cheon S. A., Kim E. J., Moon H. Y., et al. (2008). Glycoengineering of the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha for the production of glycoproteins with trimannosyl core N-glycan by blocking core oligosaccharide assembly. Biotechnol. J. 3, 659–668. 10.1002/biot.200700252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W., Aguilar F., Wang T., Qiu B. (2013). Secretion of truncated recombinant rabies virus glycoprotein with preserved antigenic properties using a co-expression system in Hansenula polymorpha. J. Microbiol. 51, 234–240. 10.1007/s12275-013-2337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W., Song H., Liu Y., Zhang C., Niu Z., Wang H., et al. (2009). Improved gene disruption method and Cre- loxP mutant system for multiple gene disruptions in Hansenula polymorpha. J. Microbiol. Methods 79, 253–259. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani-Rad M., Hollenberg C. P., Lauber J., Wedler H., Griess E., Wagner C., et al. (2003). The Hansenula polymorpha (strain CBS4732) genome sequencing and analysis. FEMS Yeast Res. 4, 207–215. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke W. C., Neiditch B. R., Hendricks M., Cregg J. M. (1996). Inducible expression of a heterologous protein in Hansenula polymorpha using the alcohol oxidase 1 promoter of Pichia pastoris. Gene 177, 163–167. 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00293-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravin N. V., Eldarov M. A., Kadnikov V. V., Beletsky A. V., Schneider J., Mardanova E. S., et al. (2013). Genome sequence and analysis of methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha DL1. BMC Genomics 14:837. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R., Haridas S., Wolfe K. H., Lopes M. R., Hittinger C. T., Göker M., et al. (2016). Comparative genomics of biotechnologically important yeasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 9882–9887. 10.1073/pnas.1603941113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchala J., Kurylenko O. O., Soontorngun N., Dmytruk K. V., Sibirny A. A. (2017). Transcriptional activator Cat8 is involved in regulation of xylose alcoholic fermentation in the thermotolerant yeast Ogataea (Hansenula) polymorpha. Microb. Cell Fact. 16, 1–13. 10.1186/s12934-017-0652-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryabova O. B., Chmil O. M., Sibirny A. A. (2003). Xylose and cellobiose fermentation to ethanol by the thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 4, 157–164. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00146-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraya R., Krikken A. M., Kiel J. A. K. W., Baerends R. J. S., Veenhuis M., van der Klei I. J. (2012). Novel genetic tools for Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 12, 271–278. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigawi S., Smutok O., Demkiv O., Gayda G., Nitzan Y., Vus B., et al. (2014). Detection of waterborne and airborne formaldehyde: from amperometric chemosensing to a visual biosensor based on alcohol oxidase. Materials 7, 1055–1068. 10.3390/ma7021055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smutok O., Dmytruk K., Gonchar M., Sibirny A., Schuhmann W. (2007). Permeabilized cells of flavocytochrome b2 over-producing recombinant yeast Hansenula polymorpha as biological recognition element in amperometric lactate biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 23, 599–605. 10.1016/j.bios.2007.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smutok O., Karkovska M., Prokopiv T., Kavetskyy T., Sibirnyj W., Gonchar M. (2018). D-lactate-selective amperometric biosensor based on the mitochondrial fraction of Ogataea polymorpha recombinant cells. Yeast. 10.1002/yea.3372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn J., Choi E., Kim C., Agaphonov M. O. (1996). A Novel autonomously replicating sequence (ARS) for multiple integration in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha DL-1. J. Bacteriol. 178, 4420–4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn J. H., Choi E. S., Kang H. A., Rhee J. S., Agaphonov M. O., Ter-Avanesyan M. D., et al. (1999). A dominant selection system designed for copy-number-controlled gene integration in Hansenula polymorpha DL-1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51, 800–807. 10.1007/s002530051465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasyk O. V., Stasyk O. G., Komduur J., Veenhuis M., Cregg J. M., Sibirny A. A. (2004). A Hexose Transporter Homologue Controls Glucose Repression in the Methylotrophic Yeast Hansenula polymorpha. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8116–8125. 10.1074/jbc.M310960200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckmann C., Scheidle M., Dittrich B., Merckelbach A., Hehmann G., Melmer G., et al. (2009). Process development in Hansenula polymorpha and Arxula adeninivorans, a re-assessment. Microb. Cell Fact. 8:22. 10.1186/1475-2859-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C., Li L., Jin Z., Han X., Zhao P., Wang L., et al. (2017). Fermentation, purification and immunogenicity evaluation of hepatitis E virus-like particles expressed in Hansenula polymorpha. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 33, 653–663. 10.13345/j.cjb.160387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh S. O., Zhou J. J. (2010). Methylotrophic yeasts near Ogataea (Hansenula) polymorpha: a proposal of Ogataea angusta comb. nov. and Candida parapolymorpha sp. nov. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 631–638. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppi S., Michelson T., Viigand K. (2013). Repression vs. activation of MOX, FMD, MPP1 and MAL1 promoters by sugars in Hansenula polymorpha: the outcome depends on cell's ability to phosphorylate sugar. FEMS Yeast Res. 13, 219–232. 10.1111/1567-1364.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebkhan Y., Samadi T., Samie A., Barkhordari F., Azizi M., Khalaj V., Mirabzadeh E. (2016). Expression of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) in Hansenula polymorpha. Iran J. Microbiol. 8, 21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhomirova L. P., Ikonomova R. N., Kuznetsova E. N., Fodor I. I. (1988). Transformation of methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha: cloning and expression of genes. J. Basic Microbiol. 28, 343–351. 10.1002/jobm.3620280509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk R., Faber K. N., Kiel J. A. K. W., Veenhuis M., Van Der Klei I. (2000). The methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha: a versatile cell factory. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26, 793–800. 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zutphen T., Baerends R. J. S., Susanna K. A., de Jong A., Kuipers O. P., Veenhuis M., et al. (2010). Adaptation of Hansenula polymorpha to methanol: a transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics 11:1. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaquero M. E., Barriuso J., Medrano F. J., Prieto A., Martínez M. J. (2015). Heterologous expression of a fungal sterol esterase/lipase in different hosts: effect on solubility, glycosylation and production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 120, 637–643. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl T., Glieder A. (2013). Regulation of Pichia pastoris promoters and its consequences for protein production. N. Biotechnol. 30, 385–404. 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronovsky A. Y., Rohulya O. V., Abbas C. A., Sibirny A. A. (2009). Development of strains of the thermotolerant yeast Hansenula polymorpha capable of alcoholic fermentation of starch and xylan. Metab. Eng. 11, 234–242. 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Deng A., Zhang Y., Liu S., Liang Y., Bai H., et al. (2018). Efficient CRISPR – Cas9 mediated multiplex genome editing in yeasts. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11:277. 10.1186/s13068-018-1271-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Wang Y. J., Li G. Q., Sun N., Liu D. H. (2011). Expression, characterization, and antimicrobial ability of T4 lysozyme from methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha A16. Sci. China Life Sci. 54, 520–526. 10.1007/s11427-011-4174-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel D., Müller J. M., Flaschel E., Friehs K., Risse J. M. (2016). Fed-batch production and secretion of streptavidin by Hansenula polymorpha: evaluation of genetic factors and bioprocess development. J. Biotechnol. 225, 3–9. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel D., Rolf T., Suckow M., Merz J., Kranz A., Barbian A., et al. (2018). Establishment of a yeast-based VLP platform for antigen presentation. Microb. Cell Fact. 17, 1–17. 10.1186/s12934-018-0868-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickerham L. J. (1951). Taxonomy of Yeasts. Technical Bulletin No. 1029. Washington, DC: US Department Agriculture, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Ren S., Chen X., Ge J., Xu Z., Huang H., et al. (2014). Generation of hepatitis B virus PreS2-S antigen in Hansenula polymorpha. Virol. Sin. 29, 403–409. 10.1007/s12250-014-3508-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn J. K., Shang L., Kim M. I., Jeong C. M., Chang H. N., Hahm M. S., et al. (2010). Enhanced production of human serum albumin by fed-batch culture of Hansenula polymorpha with high-purity oxygen. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 1534–1538. 10.4014/jmb.0909.09046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]